Abstract

Gas gangrene is a life-threatening, necrotising soft tissue infection. Colorectal malignancy-associated Clostridiumsepticum is a rare cause of gas gangrene. This case outlines an initial presentation of colonic malignancy as gas gangrene from C.septicum infection.

A 69-year-old man presented with abdominal pain, vomiting and constipation. Abdominal X-ray revealed dilated small bowel loops. Lactate was elevated. A diagnosis of small bowel obstruction was made. Subsequent CT revealed caecal thickening and subcutaneous emphysema overlying the left flank. Clinically, he became haemodynamically unstable. Examination revealed crepitus overlying the left flank in keeping with gas gangrene. The patient required immediate surgical debridement. Tissue specimens cultured C.septicum. Following a complicated postoperative period, he was transferred to the plastic surgery team for further tissue debridement and reconstruction. A colonoscopy was later performed which was suspicious for malignancy. Colorectal multidisciplinary team discussion is awaited.

Keywords: colon cancer, general surgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, infections

Background

Gas gangrene or Clostridium myonecrosis is a rare, life-threatening necrotising soft tissue infection. The underlying aetiology is usually trauma or surgery. Non-traumatic gas gangrene is much more infrequent and more often associated with underlying malignancy or immunosuppression. The organism most frequently associated with cases of non-traumatic gas gangrene is Clostridium septicum.

This case study illustrates the clinical presentation of colorectal malignancy-associated C. septicum and the rapid deterioration that ensued. The initial presentation was in keeping with small bowel obstruction secondary to a caecal malignancy; however, the development of clinical signs of gas gangrene necessitated urgent surgical debridement and intravenous antibiotic therapy. The difficulty with dual pathology is the potential for important clinical signs to be overlooked. Fortunately, this man was diagnosed promptly and appropriate intervention was initiated. Failure to promptly diagnose this life-threatening condition has a potentially fatal outcome.

Urgent surgical debridement and intravenous antibiotics is the mainstay of treatment. Adequate and often extensive tissue debridement is often required to gain source control of sepsis. Once microbial sensitivities are obtained, targeted antibiotic therapy can be commenced. In the presence of bacteraemia and septic shock, patients may require inotropic support; therefore, it is imperative to involve the intensive care team early. Long-term management invariably involves major reconstruction and grafting for which specialist plastic surgery input is required.

Case presentation

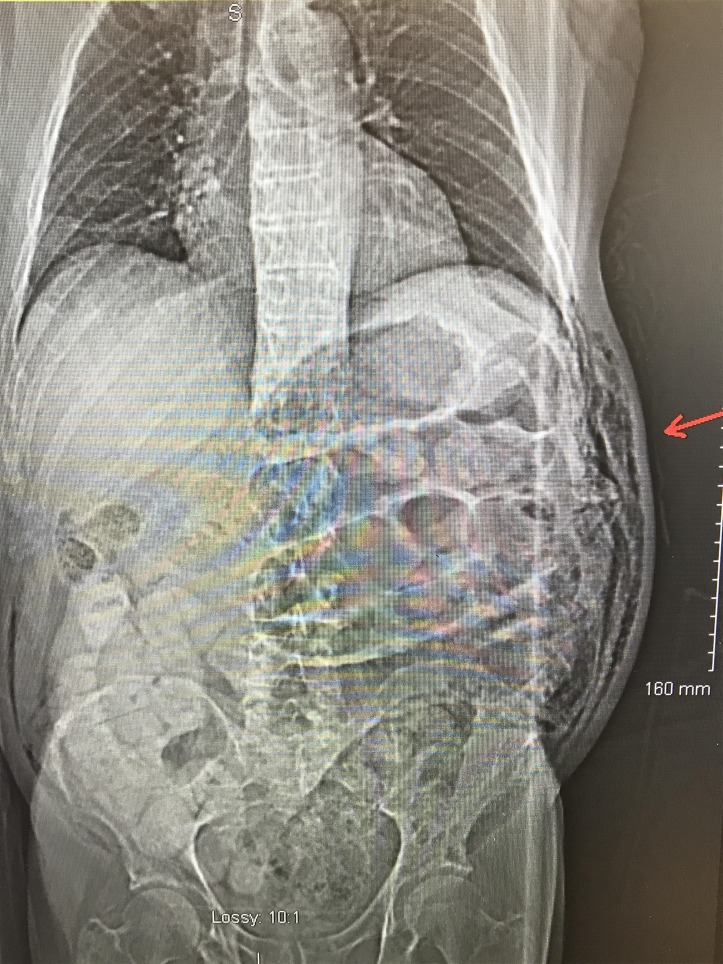

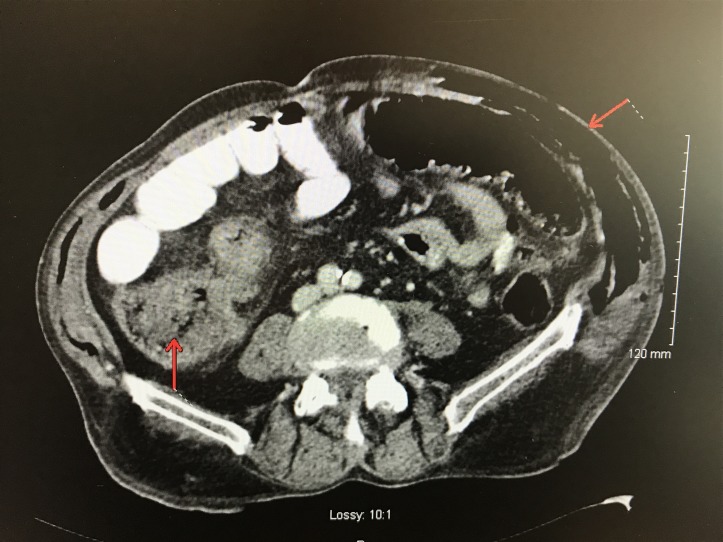

A 69-year-old man with a medical history of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, congestive cardiac failure and previous cerebral vascular accident presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. He reported that he had a few episodes of ‘dark brown’ vomit and ‘dark colour stools’ on the background of altered bowel habits for over a year and significant weight loss. On examination, his abdomen was diffusely tender and distended, with no obvious overlying skin changes. Bowels sounds were present. A digital rectal examination was performed revealing dark red stools. He was afebrile and border hypotensive. The abdominal plain film revealed dilated bowel loops. Initial laboratory investigations included lactate 4.8, haemoglobin 10.6, albumin 18 and C-reactive protein 170. The working diagnosis was small bowel obstruction. A CT of the abdomen was performed soon after admission and this reported caecal thickening with small bowel dilatation and surgical emphysema of the left flank (figures 1 and 2). Initial management included fluid resuscitation, decompression of the stomach with a nasogastric tube, intravenous antibiotics and blood grouping for potential blood transfusion.

Figure 1.

CT abdomen sagittal plane (arrow pointing to subcutaneous emphysema left flank).

Figure 2.

CT abdomen coronal plane (arrows pointing to subcutaneous emphysema overlying left flank and thickened caecum).

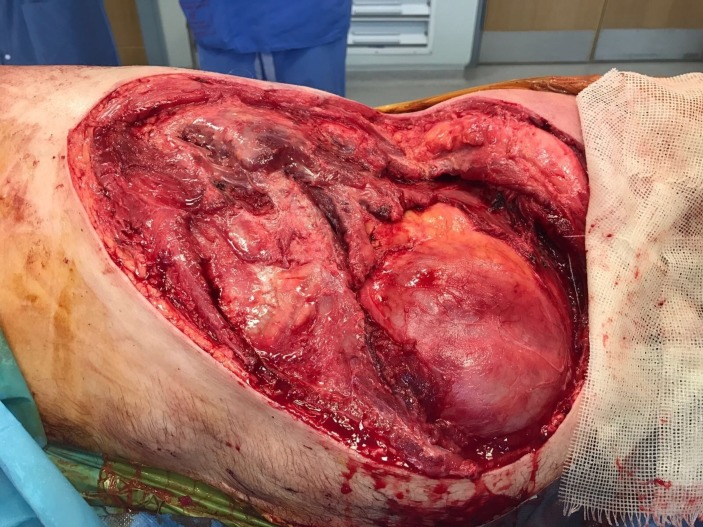

Later that day, the patient became haemodynamically unstable with signs of septic shock (systolic blood pressure dropped to 50 mm Hg). On examination of the abdomen, bruising, boggy swelling and crepitus over the left flank and abdomen were apparent (figure 3). Similar signs were also developing over the posterior forearm (figure 4). The patient was discussed with the intensive care team and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for both inotropic and respiratory support. The working diagnosis was that of gas gangrene. A creatine kinase value of 890 was concordant with this. The patient was taken to emergency theatre for debridement of the left flank and abdomen extending from his anterior superior iliac spine beyond his costal margin (figure 5). His left posterior forearm was debrided from his wrist to his elbow (figure 6). Post operation, he was transferred to the ICU while intubated and ventilated and on inotropic support. In line with microbiology advice, he was commenced on intravenous vancomycin, clindamycin and metronidazole.

Figure 3.

Image of left flank predebridement.

Figure 4.

Image of left posterior forearm predebridement.

Figure 5.

Image of left flank postdebridement.

Figure 6.

Image of left posterior forearm postdebridement.

On the third and fifth day of admission, he was brought back to theatre for further debridement of the wounds and change of dressings. Specimen cultures identified the causative organisms as C. septicum and Candida krusei. The microbiology team provided input regarding targeted antibiotic therapy.

On day 13 of admission, the patient was transferred to the care of the Plastic Surgery Service. He was successfully weaned off ventilatory and inotropic support and underwent multiple successful attempts of reconstruction. He was transferred back to the referring unit 2 months later for rehabilitation. During this admission, he developed a number of different issues including anaemia, poor glycaemic control, hypoalbuminaemia and an ischaemic left second digit (the latter requiring an amputation). Once stable, he underwent a colonoscopy that revealed a tumour in the caecum. Biopsies were obtained. Histopathological analysis confirmed fragments of adenomatous colonic mucosa with high-grade dysplasia, suspicious for malignancy.

Investigations

Urgent haematological investigations were requested including full blood count, liver function test, urea and electrolytes, coagulation screen, venous blood gas and blood grouping. The raised lactate was an immediate cause for concern.

Radiological investigations included plain film imaging of the abdomen and CT. The abdominal film revealed slightly dilated small bowel loops and an empty rectum.

The initial clinical picture was in keeping with small bowel obstruction; therefore, a CT was arranged. This highlighted the findings of subcutaneous emphysema over the left flank and caecal thickening. Further examination of the patient revealed crepitus and boggy swelling over the left flank and forearm. A creatine kinase level was recorded at this point which was six times the upper limit of normal, a result in keeping with soft tissue necrosis.

Following a long inpatient stay requiring intensive care input, extensive debridement and reconstruction, the patient then proceeded to have a colonoscopy. This unfortunately discovered a potentially malignant caecal tumour.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of gas gangrene was suspected, the microbiology team was consulted regarding appropriate antibiotic therapy. A decision was made to go to theatre urgently for debridement of affected soft tissue. Prior to transfer to theatre, the patient became haemodynamically unstable and required intensive care input for ventilation and inotropic support.

Outcome and follow-up

In the recovery period, the multidisciplinary team was heavily involved in this patient care throughout his admission. He received tissue viability input, respiratory physiotherapy, occupational therapy and specialist nursing. Consults were obtained from the vascular team due to ischaemic extremities and the endocrine team was involved regarding his poorly controlled diabetes. In light of his lack of motivation with the rehabilitation team, the patient underwent a psychiatric assessment which concluded that he was suffering from an adjustment reaction.

Once stable, he proceeded to have a colonoscopy, and biopsies were obtained. The histology from his caecal biopsy revealed fragments of adenomatous colonic mucosa with high-grade dysplasia, suspicious for malignancy. We are awaiting an outcome from the colorectal multidisciplinary meeting.

Discussion

Gas gangrene or C. myonecrosis is a rare life-threatening illness that results in necrotising soft tissue injury. Early recognition and diagnosis is imperative as the disease course is rapid. Risk factors for developing fulminant soft tissue infections include trauma, immunosupression, diabetes and vascular disease. More specifically, gas gangrene is commonly associated with patients post surgery or trauma due to the presence of Clostridium perfringes. Only 16% of cases occur spontaneously and the organisms responsible is usually the more virulent C. septicum.1 2

Clostridium is an anaerobic, spore-forming, positive rod.2 It constitutes part of the normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract. There are over 100 different strains of Clostridium of varying clinical significance. C. septicum infection resulting in bacteraemia is extremely rare. Larson et al 3 reviewed all cases of Clostridium infection at their institution from 1966 to 1993. Among 241 cases of Clostridium, 32 cases were C. septicum infection. Overall, 50% of these patients had an associated malignancy (compared with 11% for other Clostridium infections). This relationship between underlying malignancy and C. septicum infection is well established in the literature. This dates back to 1969, during which time, Alpern and Dowell described 23 cases of malignancy among 27 proven C. septicum infections.4 More recently, a retrospective study found that 4 of 15 cases of C. septicum-positive blood cultures were associated with concurrent colon carcinoma. This study further suggests that all patients with positive blood cultures for C. septicum even without clinical suspicion of colon malignancy should be referred for colonoscopy.5

The unique relationship between gastrointestinal malignancies and C. septicum infection lies in the underlying pathological process. The gastrointestinal mucosa is breached due to tissue damage from a neoplastic process. Tissue hypoxia ensues which allows rapid proliferation of Clostridia and production of exotoxins. These exotoxins result in increased capillary permeability allowing release into the systemic circulation. The infection spreads and tends to affect areas supplied by a single artery.6 7 This is not easily explained in this case as the tumour was situated in the caecum and the area of soft tissue infection was over left abdominal wall.

C. septicum is different from its other Clostridium counterparts as it is able to invade and permeate healthy tissues. These healthy tissues then become ischaemic and necrotic; this type of environment precipitates toxin production and anaerobic fermentation by C. septicum. As fermentation continues, this manifests as gas bubbles, clinically obvious as crepitus on examination7 8 and otherwise known as C. myonecrosis.

The mortality rate associated with C. septicum ranges from 56% to 60%; this is significantly higher than all other Clostridium infections which is 26%.3 9 The majority of deaths occur within the first 24 hours if diagnosis is not suspected and appropriate treatment measures are not promptly started.9 While the relationship between gastrointestinal malignancy and C. septicum is well recognised, other potential risk factors include drug-induced immunosuppression and diabetes.10 Non-traumatic, endogenous C. septicum tends to affect the elderly population more frequently.10 Interestingly, our patient was an elderly man with poorly controlled diabetes, rendering him susceptible to C. septicum on two accounts.

Once clinically suspected, C. septicum must be urgently treated, as if left untreated, C. septicum infection almost always leads to fatal outcomes. Early administration of intravenous antibiotics and surgical debridement is essential to optimise chances of survival.11 Fortunately, this patient was urgently taken to theatre for surgical debridement in a timely manner, probably the most important aspect contributing to his survival.

The outcome could have been very different if the admitting team became distracted by the clinical presentation of subacute bowel obstruction and failed to appreciate the underlying life-threatening gas gangrene infection. The occurrence of dual pathology should always be considered in the presence of clinical findings that do not fit the initial presentation.

Learning points.

Clostridium septicum should be considered in all patients who present with non-traumatic necrotising soft tissue infections.

C. septicum is a serious life-threatening condition that requires early recognition. Crepitus on examination is a clinical sign of gas bubble formation under the skin, otherwise known as gas gangrene.

Early treatment with intravenous antibiotics according to local microbiology advice and surgical debridement is the mainstay of treatment in order to optimise patients’ chance of survival.

The diagnosis of C. septicum should be considered in patients with a known or suspected history of colorectal cancer or immunosuppression and features in keeping with gas gangrene. If C. septicum is isolated from a patient’s blood culture, colonoscopy should be considered once the patient is stable to investigate for an underlying malignancy.

One must always consider the potential for dual pathology. It is important not to become distracted by the most obvious clinical diagnosis at the expense of other essential details being overlooked.

Footnotes

Contributors: CC: Author and data collection. HE: Editing. ST: Editing and provision of images.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Perry BN, Floyd WE. Gas gangrene and necrotizing fasciitis in the upper extremity. J Surg Orthop Adv 2004;13:57-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stevens DL, Bryant AE. The role of clostridial toxins in the pathogenesis of gas gangrene. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35(Suppl 1):S93–S100. 10.1086/341928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larson CM, Bubrick MP, Jacobs DM, et al. Malignancy, mortality, and medicosurgical management of Clostridium septicum infection. Surgery 1995;118:592–8. 10.1016/S0039-6060(05)80023-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alpern RJ, Dowell VR. Clostridium septicum infections and malignancy. JAMA 1969;209:385 10.1001/jama.1969.03160160021004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mao E, Clements A, Feller E. Clostridium septicum sepsis and colon carcinoma: report of 4 cases. Case Rep Med 2011;2011:1–3. 10.1155/2011/248453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wells CL, Wilkins TD. Clostridia: sporeforming anaerobic bacilli : Baron S, Medical Microbiology. Galveston (TX): The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffin AS, Crawford MD, Gupta RT. Massive gas gangrene secondary to occult colon carcinoma. Radiol Case Rep 2016;11:67–9. 10.1016/j.radcr.2016.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stevens DL, Musher DM, Watson DA, et al. Spontaneous, nontraumatic gangrene due to Clostridium septicum . Rev Infect Dis 1990;12:286–96. 10.1093/clinids/12.2.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nanjappa S, Shah S, Pabbathi S. Case Report: Clostridium septicum Gas Gangrene in Colon Cancer: Importance of Early Diagnosis, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartel M, Kutup A, Gehl A, et al. Foudroyant course of an extensive Clostridium septicum gas gangrene in a diabetic patient with occult carcinoma of the colon. Case Rep Orthop 2013;2013:216382 10.1155/2013/216382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ballard J, Bryant A, Stevens D, et al. Purification and characterization of the lethal toxin (alpha-toxin) of Clostridium septicum . Infect Immun 1992;60:784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]