Abstract

Small RNA (sRNA)-induced RNA interference (RNAi) is an important conserved mechanism that modulates gene expression in almost all eukaryotes. Some sRNAs move short distances from cell to cell, while some travel long distances to spread systemically throughout the organism. Recent studies indicate that sRNAs can even move between organisms to induce gene silencing, a phenomenon called “cross-kingdom RNAi”. sRNA trafficking between a pathogen, pest, or symbiont and its respective host can have a significant impact on interaction compatibility. Certain sRNAs were found to travel from pathogens or pests into host cells and suppress host immunity to achieve successful infection in both plants and animals; while sRNAs generated from host cells also translocate into pathogen or parasite cells to inhibit their virulence. Such cross-kingdom RNAi mechanisms enable the development of efficient disease control methods using plant-derived RNAs that target essential genes of pathogens and pests. Moreover, uptake of exogenous RNAs from the environment was recently discovered in certain fungal pathogens, which makes it possible to suppress fungal diseases by directly applying pathogen–targeting RNAs on crops and post-harvested products to avoid extensive chemical treatment and circumvent generating genetically modified plants. This spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) strategy is environmentally sustainable and friendly, and can be easily adapted to control multiple fungal diseases simultaneously.

Introduction

Crop plants are constantly under attack by many pathogens and pests during both pre- and post-harvest stages, causing devastating food and economic losses worldwide. It has been estimated that in the field, microbial pathogens and pests cause up to 14.5% and 15.1% crop yield losses, respectively, despite extensive use of fungicides and pesticides [1]. Although it has been largely overlooked, destruction caused by post-harvest diseases during processing, transportation, and storage account for 20–25% crop reduction in the United States and up to 50% in some developing countries [2,3]. Current practices to control these diseases rely heavily on chemical treatments, which pose a serious threat to human health and the environment. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a more effective, sustainable, and environmentally friendly means to protect crops from pathogens and pests before and after harvest. This review describes the current understanding of cross-kingdom RNAi and RNA trafficking between pathogens/pests and their interacting hosts and environmental RNAi in fungal pathogens, as well as how these findings can be developed disease control methods.

Small RNAs and small RNA trafficking within an organism

Small RNAs (sRNAs) are short, non-coding regulatory RNAs that silence genes with appropriate base complementarity. sRNAs are generated from double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) or single-stranded RNAs with stem-loop structures by the RNase III-type endoribonucleases, Dicer or Dicer-like (DCL) proteins. sRNAs are loaded into Argonaute (AGO) proteins to silence target genes by RNA interference (RNAi) [4,5]. RNAi is a conserved eukaryotic gene regulatory mechanism that affects almost every biological process within an organism.

Some sRNAs are mobile and induce silencing of target genes non-cell autonomously. Within an organism, selective sRNAs were observed to move short distances from cell to cell or move systemically throughout the organism. Plant sRNAs move into neighboring cells most likely through the intercellular “bridge” plasmodesmata [6,7] or systemically via the phloem vascular structure [8-11]. Some sRNAs, including the 24 nt long heterochromatic sRNAs, move through grafting junctions via vasculature [8]. Although animal cells lack plasmodesmata, they have similar “gap junction” structures for intercellular connections that are responsible for sRNA trafficking between adjacent cells [12-14]. For example, human macrophages transfer endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs) to hepato-carcinoma cells mostly through gap junctions [15]. In C. elegans, a transmembrane protein systemic RNA interference defective-1 (SID-1) acts as a similar channel for intercellular RNA movement [16,17]. Several other SID proteins that contribute to systemic RNAi and sRNA movement were identified [18,19]. However, the proteins found in C. elegans that are responsible for sRNA movement are mostly specific to C. elegans and other nematodes [16,18,19], share no or very limited homologies to proteins in other species. In addition, several other RNA trafficking pathways between animal cells have been reported. Human sRNAs are transferred with AGO2 protein [20,21], high-density lipoprotein (HDL) lipid complexes [22] or extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs are extracellular membranous vesicles that range from 40 to 1000 nm in diameter, which can be divided into two classes, including exosomes and ectosome (also called microvesicles, shedding vesicles, or microparticles), based on their size and origin [23,24]. Exosomes and ectosomes are derived from late endosomal membrane and plasma membrane, respectively [23,24]. They enable intercellular sRNA movement in animals, which also allows systemic spread of sRNAs in circulatory fluids [25-29]. Some miRNAs are transferred through apoptotic bodies following donor cell death [30]. Furthermore, extracellular miRNAs found in blood plasma and cell culture are predominantly associated with AGO proteins and are independent of vesicles.

Cross-Kingdom sRNA trafficking from pathogens and parasites into their hosts

In addition to sRNA trafficking within an organism, recent studies indicate that sRNAs can move between a host and interacting pathogens or parasites to induce gene silencing through a phenomenon called “cross-kingdom RNAi” [31,32].

Some plant and animal pathogens and pests are capable of delivering sRNAs into host cells to modulate host immune responses [33,34] (Figure 1). For example, the filamentous plant fungal pathogen B. cinerea, which causes grey mold disease on almost all vegetables, fruits, and flowers, has evolved an aggressive virulence mechanism using cross-kingdom RNAi [35]. Upon infection, B. cinerea delivers a group of sRNAs into host plant cells. These transferred sRNAs are loaded into the host Arabidopsis AGO1 protein to silence host immunity genes, such as mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and a cell wall associated kinase, etc [35-37]. It has been long known that pathogens deliver effectors, mostly proteins, into host cells to suppress host immunity [38]. These sRNAs from B. cinerea function as a novel class of pathogen effectors [35,37], which have the characteristic features that allow them to be loaded into host Arabidopsis AGO1 protein. Consistent with this finding, B. cinerea causes much less disease symptoms on the Arabidopsis ago1-27 mutant compared to wild type plants because sRNA effectors could no longer function without host AGO1 [35,37]. Less severe disease symptoms were also observed on Arabidopsis ago1-27 mutants infected with another fungal pathogen, Verticillium dahliae, which causes Verticillium wilt disease on many plants [39,40]. In agreement with this notion, V. dahliae sRNAs that have potential host targets are more predominantly associated with Arabidopsis AGO1 than AGO2 during infection [40]. These studies suggest V. dahliae also uses sRNAs as effectors to silence host target genes through Arabidopsis AGO1. Furthermore, the B. cinerea dcl1 dcl2 double mutant strain that fails to produce sRNA effectors is compromised in pathogenicity on various plant species, including vegetables, fruits, and flowers, as compared to the wild type B. cinerea; whereas B. cinerea dcl1 or dcl2 single mutant, which exhibits significant growth defect on plates and on plants but can still produce sRNA effectors, still maintain aggressive virulence, supporting that sRNA effectors are essential for B. cinerea pathogenicity [35,40].

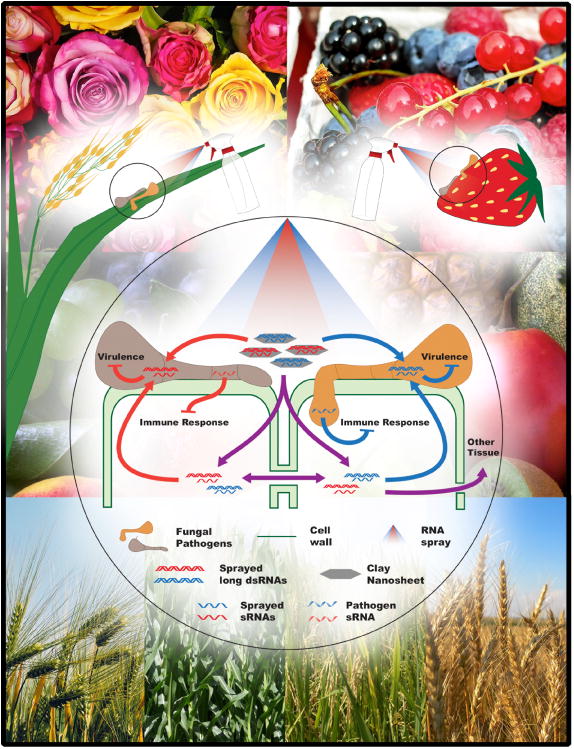

Figure 1. Cross-kingdom RNAi and spray induced gene silencing are effective strategies for preventing pre- and post-harvest diseases.

This schematic illustrates the movement of RNAs between plant fungal pathogens and their hosts and how spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) can be used to counteract pathogen virulence. Pathogen-derived sRNA effectors are delivered into the host, where they suppress host immune responses (red and blue block arrows). The spray application of gene-specific RNAs can suppress virulence through RNA interference in multiple pathogens (red and blue block arrows) either on crops or post-harvest products. These RNAs can either translocate directly to the eukaryotic pathogen or indirectly through the host (red and blue arrows). SIGS-based protection can be prolonged by incorporated RNAs into clay nanosheets (in grey) that protect RNAs from degradation and from being washed away. These RNAs can also spread systemically between cells or to other tissues in the plant (purple arrows), most likely through plasmodesmada and vascular phloem structures. The background represents the variety of crops and post-harvest products in which SIGS can be used to prevent loss from disease.

Similar observations of cross-kingdom sRNA trafficking were made also in animal systems [41-45]. For example, the gastrointestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus delivers sRNAs into mice gut epithelial cells [45]. It has been shown that exosomes, a distinct type of EVs, are largely responsible for sRNA trafficking between cells or systemically within an animal organism [25-29]. Buck et al. demonstrated that H. polygyrus exosomes are also responsible for delivering miRNAs into host cells to suppress host inflammation and immunity genes, including regulators of MAPK pathways [45]. Animal parasites secrete exosomes that contain sRNAs, which are internalized into host cells and likely silence host target genes [41-45]. Moreover, exosomes protect sRNAs from degradation by RNases in body fluids, which explains why the sRNAs remain stable and active after traveling into host cells [42,45]. Whether EV-mediated sRNA trafficking is a general pathway for sRNA transfer from pathogens/pests to hosts is unknown. Various RNA molecules, including sRNAs, are present in EVs isolated from human pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans, Paracoccidiodes brasiliensis and Candida albicans, and from the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae [46]. It is possible that EVs mediate RNA export and communication with host cells during infection. Apart from EV-mediated trafficking, some proteins evolved to facilitate RNA trafficking in certain organisms, as in the case of C. elegans, which is discussed in the environmental RNAi section below.

Communications through sRNAs and cross-kingdom RNAi may exist between many interacting organisms, including those with a beneficial symbiotic relationship [47]. In fact, genome sequencing analysis has revealed a set of miRNAs of the dinoflagellate symbiont Symbiodinium kawagutii, an important photosynthetic endosymbiont of coral that can potentially target its own genes and coral host genes. The predicted host target genes have similar putative functions as the endogenous S. kawagutii miRNA targets, suggesting that these mobile miRNAs may modulate similar biological processes in both host and symbiont [47].

Interestingly, such RNA movement to host cells is not limited to eukaryotic pathogens or pests. Prokaryotes do not have RNAi machinery, they produce small non-coding RNAs that are 70-200 nt in length. In fact, in the endosymbiotic host-bacteria interactions, two bacterial small non-coding RNA WsnRNA-46 and WsnRNA-49 from Wolbachia, a symbiotic bacterium infects many arthropod species, can regulate the target genes from the mosquitoes host Aedes aegypti in addition to its own genes [48].

Cross-Kingdom sRNA trafficking from hosts to pathogens or parasites

Host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) is an excellent example of sRNA trafficking from hosts to interacting pathogens or pests and has been extensively investigated during the last decade for as a method of crop protection [49-53]. Transgenic plants and crops expressing sRNAs that target essential growth and virulence genes of eukaryotic pathogens and pests are resistant/tolerant to disease [49-53] (Figure 1). For example, cotton bollworm larva fed plant material expressing dsRNAs that target and reduce the expression of a cytochrome P450 gene are more sensitive to the anti-herbivory plant compound gossypol [52]. Moreover, transgenic barley plants expressing dsRNAs targeting the fungal pathogen Blumeria graminis development gene that encoding 1,3-β-glucanosyltransferase (GTF1) or effector genes Avra10 and Avrk1 displayed significantly reduced disease symptoms caused by B. graminis [50]. Direct evidence that sRNA is transferred from host to pathogen in HIGS was provided by Wang et al. [40]. Host-derived B. cinerea DCL1/2-targeting sRNAs were identified in the interacting B. cinerea dcl1 dcl2 mutant strain. Because the dcl1 dcl2 mutant B. cinerea strain can no longer process dsRNA precursors into sRNAs, it eliminates the possibility that the sRNAs detected in dcl1 dcl2 were processed by fungal DCLs [40]. Although various forms of RNAs may have the potential to move across organism boundaries, this result supports that sRNAs are at least one of the major mobile signals for cross-kingdom RNAi. Such bidirectional RNA trafficking was also observed in the interaction between an invertebrate host and its parasite. In the interaction between the honey bee (Apis mellifera) and its obligatory ectoparasite Varroa mite, ingested artificial dsRNAs are transferred from A. mellifera to Varroa and vice versa, triggering bidirectional RNAi in trans [54]. These studies provide excellent examples of bidirectional cross-kingdom RNAi and sRNA trafficking between interacting organisms.

In addition to artificial transgene-derived sRNAs, animals and plants can also deliver endogenous sRNAs into interacting organisms [55,56]. In the interactions between human and malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, some erythrocyte miRNAs, including miR-451 and lethal-7i (let-7i), are translocated into P. falciparum [56]. Although P. falciparum lacks RNAi machinery, these transferred miRNAs utilize an alternative mode of action by forming chimeric transcripts fused to parasite target mRNAs, cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase subunit (PKA-R) and reduced expression 1 (REX1), and inhibit mRNA translation of these pathogenicity related genes [56,57]. This phenomenon may explain why patients with sickle cell anemia are more resistant to malaria, because they have elevated levels of these P. falciparum gene-targeting miRNAs [56]. In cotton, the abundant miR166 and miR159 were recently found to move into V. dahliae hyphae and down regulate two V. dahiliae target genes encoding a Ca2+-dependent cysteine protease (Clp-1) and an isotrichodermin C-15 hydroxylase (HiC-15), respectively [55]. Both Clp-1 and HiC-15 play an important role in the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. These studies suggest that plant and animal hosts also utilize cross-kingdom RNAi strategies to suppress the virulence of pathogens and parasites.

Strikingly, hosts can also deliver sRNAs into prokaryotic pathogens. In the interactions between mammalian hosts and gut bacteria, host-derived fecal miRNAs enter the gut bacterial cells and co-localize with bacterial nucleic acids to regulate transcript level of the targets, thus affect the growth of gut bacteria [58]. For example, the human miRNAs hsa-miR-1226-5p and hsa-miR-515-5p enter the gut bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn). Intriguingly, these host miRNAs increase the transcript level of their bacterial targets E. coli yegH and Fn 16s rRNA, respectively [58]. Thus, these host fecal miRNAs promote the growth of gut bacteria.

It remains to be determined how common it is for hosts to suppress disease by delivering sRNAs into interacting pathogens and pests to manipulate virulence genes. The fact that RNA trafficking-mediated defense mechanisms are present in both plant and animal hosts supports the important role of cross-kingdom RNAi in the evolution of host immune responses.

Environmental RNAi and spray-induced gene silencing

HIGS has been demonstrated to be successful in plant protection against nematodes [51], insects [52,53], fungi [40,50,59], and oomycetes [60,61]. Such sequence-based cross-kingdom RNAi strategies could be easily adapted to control multiple pathogens simultaneously by targeting essential virulent genes from different pathogens (Figure 1) [40]. Transgenic plants expressing sRNAs that target essential virulence genes DCL1 and DCL2 from both B. cinerea and V. dahliae exhibit enhanced resistance/tolerance to both fungal pathogens [40]. One of the limitations of HIGS is that it requires stable genetic transformation, which is not yet possible for many economically important crops. Additionally, the public still has concerns about genetically engineered crops, commonly known as genetically modified organisms (GMOs). It is highly desirable to develop new means of disease control without generating GMOs or extensive use of chemicals.

Uptake of external RNAs from the environment that induce RNAi, a phenomenon called “environmental RNAi”, was observed in C. elegans and several nematodes and insects [62]. Mutant screenings in C. elegans identified several SID genes that are responsible for environmental RNAi and systemic RNAi [16-19,63,64]. However, most of these genes are almost exclusively present in invertebrates but not in fungi or plants [34]. For example, SID-1 and SID-2 are two important genes that mediate dsRNA uptake. SID-1 encodes a transmembrane protein that serves as a channel for rapid and endocytosis-independent dsRNA uptake [16,17], while SID-2 is a transmembrane protein that mediates slow and endocytosis-dependent dsRNA uptake [19,63]. SID-1 has a very distant homolog in mammals but not in Drosophila, plants, or fungi [16], and SID-2 only has homologous genes in two closely related nematodes, C. briggsae and C. remanei [19].

So far, environmental RNAi has not yet been observed in mammals. It was not clear whether plants and fungi could take up RNAs from the environment until recently. Wang et al. recently demonstrated that the fungal pathogen B. cinerea is capable of taking up dsRNAs and sRNAs from the environment (Figure 1) [40]. This RNA uptake makes it possible to use dsRNAs or sRNAs that target pathogen genes directly for disease management. Indeed, spraying B. cinerea DCL1/2-targeting dsRNAs or sRNAs on the surface of fruits, vegetables, and flowers significantly inhibits grey mold diseases [40]. Spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) is also effective for disease control in monocots [65], which represent some of the most important crop species (Figure 1). Koch et al. demonstrated that spraying dsRNAs that target Fusarium graminearum cytochrome P450 lanosterol C-14α-demethylase (CYP51) genes significantly reduced disease symptoms on barley leaves [65]. Thus, these RNAs that targeting pathogen genes serve as a new generation of fungicides that are effective for both dicot and monocot crop species [66].

External RNAs may be translocated into pathogens/pests by either direct or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). RNAs could either be directly taken up by the fungal cells or be transferred into plant cells first then move into fungal cells [40,65]. Interestingly, locally sprayed RNAs also inhibit pathogen virulence at distal, non-sprayed leaves [65,67] suggesting that these RNAs are able to spread systemically within plants. It is worth noting that invertebrates typically take up dsRNAs that are longer than 50 bp in length but not shorter dsRNAs or sRNAs [17,68,69], while fungi and plants can take up both dsRNAs and sRNAs [40,65], suggesting that the invertebrates may share different uptake mechanisms compared to fungi or plants.

SIGS has also been used to control insect pests. Topically applying synthesized dsRNAs that target insect developmental genes significantly increases the rate of mortality and impairs insect growth [70-73]. Such an effect can also be achieved by irrigating plant roots with dsRNAs targeting insect genes, which efficiently leads to target gene silencing and abnormal development of the pest insects [74]. Interestingly, high mortality rates of the pest insect Plutella xylostella were observed on plant leaves sprayed with sRNAs targeting the insect P. xylostella acetylcholine esterase genes AChE1 and AChE2 [75]. These results support that gene expression within insect pests are suppressed through uptake of either dsRNAs or sRNAs.

Recent advances in nanoparticle technology have improved the potential applications of SIGS for plant protection. Naked dsRNA and sRNA treatments can protect plants from microbial pathogens up to 10 days after spraying [40,65]. A recent study indicates that the duration of protection against viral infection was extended to more than 20 days when dsRNAs were incorporated into layered double hydroxide (LDH) clay nanosheets called BioClay [67]. BioClay nanosheets prevented dsRNAs from being degraded by RNases or sunlight, or from being easily washed away from leaf surfaces by water. In fact, nanoparticles, including LDH nanoparticles, have been widely used in RNA delivery to facilitate RNAi in human therapies [76,77]. Because these nanoparticles and the RNAs within them are non-toxic and easily degradable, this technique is an environmentally conscious method that improves the efficacy of plant disease management in the field using SIGS.

SIGS provides safe and powerful plant protection not only on pre-harvest crops [65,67] but also on post-harvest products [40]. Fruits, vegetables, grains, and decorative plants succumb to post-harvest attack by microbial pathogens during processing, transportation and storage [2]. Furthermore, pathogens often produce toxic chemicals while proliferating on post-harvest products. For example, fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium produce mycotoxins on post-harvest grain products. Mycotoxins are considered carcinogenic and can pose a serious threat to consumers’ health [78]. Currently, application of fungicides and microbial antagonists is still the most commonly used strategy for controlling post-harvest diseases. Therefore, controlling post-harvest diseases using a new generation of sustainable and environmentally friendly RNA-based fungicides can help reduce the yield loss caused by post-harvest damage as well as prevent the accumulation of toxic chemicals produced by pathogens.

Conclusion

The emerging evidence on cross-kingdom RNAi and RNA trafficking has expanded our knowledge of host-pathogen interactions and potential disease management approaches. Such RNA exchange may be a common mechanism of communications present in many interacting organisms. More work is needed to understand the precise molecular mechanisms governing cross-kingdom RNA trafficking to better understand its evolution and how it shapes host-pathogen or host-pest interactions. Although isolating pure cell fractions of an individual organism from the interacting interface is still technically challenge, more and more endogenous mobile sRNAs have been identified in different organisms under different conditions [8,9,26,28,29,79,80], and their profiles are largely different from the profiles of total sRNAs. One future direction of sRNA research is to understand the molecular mechanism of mobile sRNA selection under different developmental and environmental conditions.

Simulating cross-kingdom RNAi using SIGS presents an attractive, powerful, and safe alternative to the current chemical-based applications for disease control [2]. Compared to current disease control methods, SIGS is a more targeted and environmentally friendly strategy for both post- and pre-harvest plant protection and is less detrimental to consumer health. SIGS is also environmentally sustainable, because the possibility that pathogens will evolve resistance to these RNA-based fungicides is low, as SIGS is sequence-based and does not require 100% base-pairing for effective silencing, and many nucleotide mutations in the pathogen would be required to evade the targeting sRNAs. Additionally, since SIGS often chooses to target pathogen genes that are essential for growth or virulence, the pathogens may not be able to afford evolving enough mutations in these essential genes to evade SIGS yet while retaining their vital function. Finally, we believe that SIGS would be more acceptable to the public than the use of chemical treatments, and its development would take less time than generating stable transgenic crops or GMOs.

Highlights.

Small RNAs can transfer from pathogens or parasites into their interacting hosts.

Plant and animal hosts can deliver small RNAs into interacting pathogens and parasites.

External RNAs can be taken up by fungal cells and plant cells and induce RNAi.

Spray-induced gene silencing represents an innovative disease control tool.

Acknowledgments

We apologize that we would not be able to include and cite many related interesting studies due to the limited space. The work in Jin's lab has been supported by grants from National Institute of Health (R01 GM093008), National Science Foundation (IOS-1257576, IOS-1557812) and an AES-CE Award (PPA-7517H).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Oerke EC. Crop losses to pests. J Agr Sci. 2006;144:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma RR, Singh D, Singh R. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables by microbial antagonists: A review. Biol Control. 2009;50:205–221. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kader AA. Increasing food availability by reducing postharvest losses of fresh produce. Proceedings of the 5th International Postharvest Symposium. 2005;1-3:2169–2175. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baulcombe D. RNA silencing in plants. Nature. 2004;431:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature02874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim VN, Han J, Siomi MC. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:126–139. doi: 10.1038/nrm2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaten A, Dettmer J, Wu S, Stierhof YD, Miyashima S, Yadav SR, Roberts CJ, Campilho A, Bulone V, Lichtenberger R, et al. Callose biosynthesis regulates symplastic trafficking during root development. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1144–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunkard JO, Zambryski PC. Plasmodesmata enable multicellularity: new insights into their evolution, biogenesis, and functions in development and immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;35:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molnar A, Melnyk CW, Bassett A, Hardcastle TJ, Dunn R, Baulcombe DC. Small silencing RNAs in plants are mobile and direct epigenetic modification in recipient cells. Science. 2010;328:872–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1187959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunoyer P, Schott G, Himber C, Meyer D, Takeda A, Carrington JC, Voinnet O. Small RNA duplexes function as mobile silencing signals between plant cells. Science. 2010;328:912–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1185880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voinnet O, Vain P, Angell S, Baulcombe DC. Systemic spread of sequence-specific transgene RNA degradation in plants is initiated by localized introduction of ectopic promoterless DNA. Cell. 1998;95:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81749-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhtz A, Springer F, Chappell L, Baulcombe DC, Kehr J. Identification and characterization of small RNAs from the phloem of Brassica napus. Plant J. 2008;53:739–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valiunas V, Polosina YY, Miller H, Potapova IA, Valiuniene L, Doronin S, Mathias RT, Robinson RB, Rosen MR, Cohen IS, et al. Connexin-specific cell-to-cell transfer of short interfering RNA by gap junctions. J Physiol. 2005;568:459–468. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim PK, Bliss SA, Patel SA, Taborga M, Dave MA, Gregory LA, Greco SJ, Bryan M, Patel PS, Rameshwar P. Gap Junction-Mediated Import of MicroRNA from Bone Marrow Stromal Cells Can Elicit Cell Cycle Quiescence in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1550–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katakowski M, Buller B, Wang XL, Rogers T, Chopp M. Functional MicroRNA Is Transferred between Glioma Cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8259–8263. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aucher A, Rudnicka D, Davis DM. MicroRNAs transfer from human macrophages to hepatocarcinoma cells and inhibit proliferation. J Immunol. 2013;191:6250–6260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2002;295:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1068836. This work used mutant screening to identify regulators of systemic RNA interference. The group identified the systemic RNA interference–deficient (sid) gene SID-1 in C. elegans. This gene encoded a transmembrane protein that did not affect the initiation of RNAi, but was required for the propogation of systemic RNAi and RNA transport. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2003;301:1545–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.1087117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinas A, Wright AJ, Hunter CP. SID-5 Is an Endosome-Associated Protein Required for Efficient Systemic RNAi in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1938–1943. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Winston WM, Sutherlin M, Wright AJ, Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Caenorhabditis elegans SID-2 is required for environmental RNA interference. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10565–10570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611282104. This study identified another systemic RNA interference–deficient (sid) gene SID-2 in C. elegans. SID-2 encodes a transmembrane protein expressed in the intestinal lumin. The sid-2 mutant failed to initiate RNAi after RNA soaking, while RNA injection and transgene expression still trigger systemic RNAi. This work suggested that SID-2 is required in the enviromental dsRNA uptake into the intestinal cells, but not in the systemic RNAi spreading. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, Mitchell PS, Bennett CF, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Stirewalt DL, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Langheinz A, Burwinkel B. Characterization of extracellular circulating microRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7223–7233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:423–433. doi: 10.1038/ncb2210. The authors showed that the human plasma high-density lipoprotein (HDL) associates with miRNAs and protects them from degradation during transport to recipient cells. These miRNAs maintained the ability to silence genes in the recipient cells. This study provided an alternative strategy of vesicle-free miRNA transportation in the body fluid. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittelbrunn M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Intercellular communication: diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:328–335. doi: 10.1038/nrm3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–U672. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Ochiya T. Circulating microRNA in body fluid: a new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2087–2092. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skog J, Wurdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Sena-Esteves M, Curry WT, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–U1209. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Thomou T, Mori MA, Dreyfuss JM, Konishi M, Sakaguchi M, Wolfrum C, Rao TN, Winnay JN, Garcia-Martin R, Grinspoon SK, et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. In this study, Dicer gene in the mouse adipose tissue were specifically knocked out, the exosome associated circulating miRNAs were largetly reduced, suggesting that adipose tissue is a major source for circulating miRNAs. Moreover, they also showed that the adipose tissue derived exosomal circulating miRNA could regulate the expression of target genes in the liver tissue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Koppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiberg A, Bellinger M, Jin HL. Conversations between kingdoms: small RNAs. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;32:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knip M, Constantin ME, Thordal-Christensen H. Trans-kingdom cross-talk: small RNAs on the move. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiberg A, Wang M, Bellinger M, Jin H. Small RNAs: a new paradigm in plant-microbe interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2014;52:495–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Weiberg A, Jin H. Pathogen small RNAs: a new class of effectors for pathogen attacks. Mol Plant Pathol. 2015;16:219–223. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Weiberg A, Wang M, Lin FM, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Kaloshian I, Huang HD, Jin H. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science. 2013;342:118–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1239705. The study provided the first example of naturally occurring cross-kingdom RNAi that employed as an aggressive virulence mechanism by an aggressive fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea. The fungal pathogen delivers sRNAs into host plant cells during infection and these fungal sRNAs silence host immunity genes by hijacking the host's Argonaute 1 protein. These mobile fungal sRNAs serve as a novel class of effectors to suppress host immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baulcombe D. Plant science. Small RNA--the secret of noble rot. Science. 2013;342:45–46. doi: 10.1126/science.1245010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Wang M, Weiberg A, Dellota E, Jr, Yamane D, Jin H. Botrytis small RNA Bc-siR37 suppresses plant defense genes by cross-kingdom RNAi. RNA Biol. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1291112. The authors identified a B. cinerea sRNA effector, Bc-siR37, which was produced from gene coding region. Bc-siR37 was also delivered into Arabidopsis and associated with Argonaute 1 protein to silence its host target genes. They further showed that three of these target genes, At-WRKY7, At-FEI2 and At-MR6 were involved in plant immunity against B. cinerea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kazan K, Lyons R. Intervention of Phytohormone Pathways by Pathogen Effectors. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2285–2309. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.125419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellendorff U, Fradin EF, de Jonge R, Thomma BPHJ. RNA silencing is required for Arabidopsis defence against Verticillium wilt disease. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:591–602. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40••.Wang M, Weiberg A, Lin FM, Thomma BP, Huang HD, Jin H. Bidirectional cross-kingdom RNAi and fungal uptake of external RNAs confer plant protection. Nat Plants. 2016;2:16151. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.151. This study demonstrated that cross-kingdom RNAi is bidirectional. sRNAs from transgenic plants can be delivered into pathogen cells and induce silencing of fungal genes. Moreover, this work also showed for the first time that fungal cells can directly take up sRNAs and double-stranded RNAs from the environment, which enables the development of RNA-based disease control tools. Direction application of fungal DCL-targeting RNAs largely reduced the fungal diseases on fruits, vegetables and flowers. This novel approach is more environmentally sustainable and friendly than current fungicides and is likely more socially acceptable than GMO-based approaches to disease management. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu SL, Wang S, Lin Y, Jiang PY, Cui XB, Wang XY, Zhang YB, Pan WQ. Release of extracellular vesicles containing small RNAs from the eggs of Schistosoma japonicum. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9 doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1845-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lambertz U, Ovando MEO, Vasconcelos EJR, Unrau PJ, Myler PJ, Reiner NE. Small RNAs derived from tRNAs and rRNAs are highly enriched in exosomes from both old and new world Leishmania providing evidence for conserved exosomal RNA Packaging. BMC Genomics. 2015;16 doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1260-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu LH, Liu JT, Dao JW, Lu K, Li H, Gu HM, Liu JM, Feng XG, Cheng GF. Molecular characterization of S. japonicum exosome-like vesicles reveals their regulatory roles in parasite-host interactions. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep25885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Twu O, de Miguel N, Lustig G, Stevens GC, Vashisht AA, Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson PJ. Trichomonas vaginalis Exosomes Deliver Cargo to Host Cells and Mediate Host:Parasite Interactions. Plos Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45••.Buck AH, Coakley G, Simbari F, McSorley HJ, Quintana JF, Le Bihan T, Kumar S, Abreu-Goodger C, Lear M, Harcus Y, et al. Exosomes secreted by nematode parasites transfer small RNAs to mammalian cells and modulate innate immunity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5488. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6488. This group showed that mammalian parasitic nematodes secrete exosomes that containing nematode miRNAs into host cells. These nematode miRNAs silence host genes involved in inflammation and immunity. Their results suggest that animal parasites utilize exosomes to deliver small RNAs into host cells to modulate host immunity genes via cross-kingdom RNAi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peres da Silva R, Puccia R, Rodrigues ML, Oliveira DL, Joffe LS, Cesar GV, Nimrichter L, Goldenberg S, Alves LR. Extracellular vesicle-mediated export of fungal RNA. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7763. doi: 10.1038/srep07763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47•.Lin S, Cheng S, Song B, Zhong X, Lin X, Li W, Li L, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Ji Z, et al. The Symbiodinium kawagutii genome illuminates dinoflagellate gene expression and coral symbiosis. Science. 2015;350:691–694. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0408. Genome sequencing of the endosymbiont dinoflagellate Symbiodinium kawagutii revealed a group of miRNAs that have the potential to target host coral genes as well as similar genes of its own, suggesting that these miRNAs may regulate gene expression in both the symbiont and the host. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayoral JG, Hussain M, Joubert DA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, O'Neill SL, Asgari S. Wolbachia small noncoding RNAs and their role in cross-kingdom communications. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:18721–18726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420131112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nunes CC, Dean RA. Host-induced gene silencing: a tool for understanding fungal host interaction and for developing novel disease control strategies. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13:519–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowara D, Gay A, Lacomme C, Shaw J, Ridout C, Douchkov D, Hensel G, Kumlehn J, Schweizer P. HIGS: Host-Induced Gene Silencing in the Obligate Biotrophic Fungal Pathogen Blumeria graminis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3130–3141. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.077040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51••.Huang GZ, Allen R, Davis EL, Baum TJ, Hussey RS. Engineering broad root-knot resistance in transgenic plants by RNAi silencing of a conserved and essential root-knot nematode parasitism gene. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14302–14306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604698103. This work showed that transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing dsRNAs that target a nematode parasitism gene were resistant against root knot nematodes. This was the first report of host-induced gene silencing for plant protection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52••.Mao YB, Cai WJ, Wang JW, Hong GJ, Tao XY, Wang LJ, Huang YP, Chen XY. Silencing a cotton bollworm P450 monooxygenase gene by plant-mediated RNAi impairs larval tolerance of gossypol. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt1352. In this paper, the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) insect pest was fed with cotton leaves expressing dsRNAs that target a cytochrome P450 gene (CYP6AE14), which is important for cotton bollworm tolerance to gossypol. Suppression of this gene impaired the larval growth, supporting that host-induced gene silencing is also efficient for plant protection against insect pests. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53••.Baum JA, Bogaert T, Clinton W, Heck GR, Feldmann P, Ilagan O, Johnson S, Plaetinck G, Munyikwa T, Pleau M, et al. Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1322–1326. doi: 10.1038/nbt1359. The authors showed that injecting dsRNAs that targeting several coleopteran insect pest genes induced gene silencing and led to significant lavarl mortality. Moreover, in planta expression of insect gene-targeting dsRNAs significantly protected plants from western corn rootworm (WCR) Diabrotica virgifera virgifera LeConte. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garbian Y, Maori E, Kalev H, Shafir S, Sela I. Bidirectional Transfer of RNAi between Honey Bee and Varroa destructor: Varroa Gene Silencing Reduces Varroa Population. Plos Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55••.Zhang T, Zhao YL, Zhao JH, Wang S, Jin Y, Chen ZQ, Fang YY, Hua CL, Ding SW, Guo HS. Cotton plants export microRNAs to inhibit virulence gene expression in a fungal pathogen. Nat Plants. 2016;2:16153. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.153. This work showed that several abundant cotton endogenous miRNAs were delivered into fungal pathogen Verticillium dahliae to induce trans-kingdom RNAi and suppressed pathogen virulence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56••.LaMonte G, Philip N, Reardon J, Lacsina JR, Majoros W, Chapman L, Thornburg CD, Telen MJ, Ohler U, Nicchitta CV, et al. Translocation of Sickle Cell Erythrocyte MicroRNAs into Plasmodium falciparum Inhibits Parasite Translation and Contributes to Malaria Resistance. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.007. Sickle cell erythrocytes of anemia patients accumulate higher levels of miR-451 and let-7i, which are transferred into parasite P. falciparum cells. These miRNAs are fused with targeted parasite mRNAs at 5′ UTR region and form chimeric structures that suppress mRNA translation. This work provided evidence that animal hosts also export sRNAs into interacting parasite cells and suppress its virulence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duraisingh MT, Lodish HF. Sickle Cell MicroRNAs Inhibit the Malaria Parasite. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:127–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Liu S, da Cunha AP, Rezende RM, Cialic R, Wei Z, Bry L, Comstock LE, Gandhi R, Weiner HL. The Host Shapes the Gut Microbiota via Fecal MicroRNA. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.005. In this study, the miRNAs in the mouse and human feces have been identified. These host fecal miRNAs entered the bacteria cells and regulated the transcript level of gut bacteria targets, thus affected the growth of gut bacteria. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koch A, Kumar N, Weber L, Keller H, Imani J, Kogel KH. Host-induced gene silencing of cytochrome P450 lanosterol C14 alpha-demethylase-encoding genes confers strong resistance to Fusarium species. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19324–19329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306373110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vega-Arreguin JC, Jalloh A, Bos JI, Moffett P. Recognition of an Avr3a Homologue Plays a Major Role in Mediating Nonhost Resistance to Phytophthora capsici in Nicotiana Species. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014;27:770–780. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-14-0014-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jahan SN, Asman AKM, Corcoran P, Fogelqvist J, Vetukuri RR, Dixelius C. Plant-mediated gene silencing restricts growth of the potato late blight pathogen Phytophthora infestans. J Exp Bot. 2015;66:2785–2794. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Whangbo JS, Hunter CP. Environmental RNA interference. Trends Genet. 2008;24:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McEwan DL, Weisman AS, Huntert CP. Uptake of Extracellular Double-Stranded RNA by SID-2. Mol Cell. 2012;47:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jose AM, Kim YA, Leal-Ekman S, Hunter CP. Conserved tyrosine kinase promotes the import of silencing RNA into Caenorhabditis elegans cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14520–14525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201153109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65••.Koch A, Biedenkopf D, Furch A, Weber L, Rossbach O, Abdellatef E, Linicus L, Johannsmeier J, Jelonek L, Goesmann A, et al. An RNAi-Based Control of Fusarium graminearum Infections Through Spraying of Long dsRNAs Involves a Plant Passage and Is Controlled by the Fungal Silencing Machinery. Plos Pathog. 2016;12:e1005901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005901. This study demonstrated that RNAs sprayed on the surface of barley leaves are taken up by the plant cells and then travel into fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum cells to silence pathogen virulence genes. The RNAs can also systemically move into untreated leaf parts to inhibit fungal infection. This study showed that RNA spray induced gene silencing is an effective tool for plant protection against fungal pathogens in a monocot. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang M, Jin H. Spray-Induced Gene Silencing: a Powerful Innovative Strategy for Crop Protection. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Mitter N, Worrall EA, Robinson KE, Li P, Jain RG, Taochy C, Fletcher SJ, Carroll BJ, Lu GQ, Xu ZP. Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat Plants. 2017;3:16207. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.207. This report showed that topical application of dsRNAs on the plant leaves can protect the plants from viral infection. More importantly, the protection can be significantly extended when loading the dsRNAs on layered double hydroxide (LDH) clay nanosheets, because the LDH clay nanosheets protect dsRNAs from degradation and from being washed off from plant leaves. This was the first example of using nanosheets to deliver dsRNAs for plant protection. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68•.Saleh MC, van Rij RP, Hekele A, Gillis A, Foley E, O'Farrell PH, Andino R. The endocytic pathway mediates cell entry of dsRNA to induce RNAi silencing. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:793–U719. doi: 10.1038/ncbl439. Genome-wide genetic screening identified several receptors in the endocytosis pathways that are involved in dsRNA uptake in Drosophila melanogaster S2 cells. The authors showed that homologs of these genes in C. elegans are also essential for the spread of systemic RNAi, which suggests that endocytosis-mediated dsRNA uptake pathway might be evolutionarily conserved. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ivashuta S, Zhang YJ, Wiggins BE, Ramaseshadri P, Segers GC, Johnson S, Meyer SE, Kerstetter RA, McNulty BC, Bolognesi R, et al. Environmental RNAi in herbivorous insects. RNA. 2015;21:840–850. doi: 10.1261/rna.048116.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pridgeon JW, Zhao LM, Becnel JJ, Strickman DA, Clark GG, Linthicum KJ. Topically applied AaeIAP1 double-stranded RNA kills female adults of Aedes aegypti. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:414–420. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[414:taadrk]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang YB, Zhang H, Li HC, Miao XX. Second-Generation Sequencing Supply an Effective Way to Screen RNAi Targets in Large Scale for Potential Application in Pest Insect Control. Plos One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Killiny N, Hajeri S, Tiwari S, Gowda S, Stelinski LL. Double-Stranded RNA Uptake through Topical Application, Mediates Silencing of Five CYP4 Genes and Suppresses Insecticide Resistance in Diaphorina citri. Plos One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.San Miguel K, Scott JG. The next generation of insecticides: dsRNA is stable as a foliar-applied insecticide. Pest Manage Sci. 2016;72:801–809. doi: 10.1002/ps.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74•.Li H, Guan R, Guo H, Miao X. New insights into an RNAi approach for plant defence against piercing-sucking and stem-borer insect pests. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:2277–2285. doi: 10.1111/pce.12546. Rice plants take up dsRNAs when their roots were soaked in dsRNA solution. These rice plants exhibit enhanced disease resistance against insect pest. This study showed that application of dsRNA through irrigation could be a potential plant protection strategy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gong L, Chen Y, Hu Z, Hu MY. Testing Insecticidal Activity of Novel Chemically Synthesized siRNA against Plutella xylostella under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ladewig K, Xu ZP, Lu GQ. Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles in gene and drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:907–922. doi: 10.1517/17425240903130585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kanasty R, Dorkin JR, Vegas A, Anderson D. Delivery materials for siRNA therapeutics. Nat Mater. 2013;12:967–977. doi: 10.1038/nmat3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Magan N, Aldred D. Post-harvest control strategies: Minimizing mycotoxins in the food chain. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;119:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sarkies P, Miska EA. Small RNAs break out: the molecular cell biology of mobile small RNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:525–535. doi: 10.1038/nrm3840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80••.Lewsey MG, Hardcastle TJ, Melnyk CW, Molnar A, Valli A, Urich MA, Nery JR, Baulcombe DC, Ecker JR. Mobile small RNAs regulate genome-wide DNA methylation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E801–E810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515072113. Genome-wide profiling of grafted Arabidopsis root materials has identified sRNAs that are overlapped in grafting sets of C24/C24 (shoot/root), C24/Col, Col/Col, and C24/dcl234 but not in dcl234/dcl234, suggesting that these sRNAs are shoot derived mobile sRNAs. These mobile sRNAs induce root DNA methylation at thousands of different loci, most of which are in non-CG contexts. This study provides an example of systemically mobile 24 nt sRNAs that direct DNA methylation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]