Abstract

The Integrated Stress Response (ISR) refers to a signaling pathway initiated by stress-activated eIF2α kinases. Once activated, the pathway causes attenuation of global mRNA translation while also paradoxically inducing stress response gene expression. A detailed analysis of this pathway has helped us better understand how stressed cells coordinate gene expression at translational and transcriptional levels. The translational attenuation associated with this pathway has been largely attributed to the phosphorylation of the translational initiation factor eIF2α. However, independent studies are now pointing to a second translational regulation step involving a downstream ISR target, 4E-BP, in the inhibition of eIF4E and specifically cap-dependent translation. The activation of 4E-BP is consistent with previous reports implicating the roles of 4E-BP resistant, Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) dependent translation in ISR active cells. In this review, we provide an overview of the translation inhibition mechanisms engaged by the ISR and how they impact the translation of stress response genes.

Keywords: eIF2, Integrated Stress Response, mRNA translation, 4E-BP

INTRODUCTION

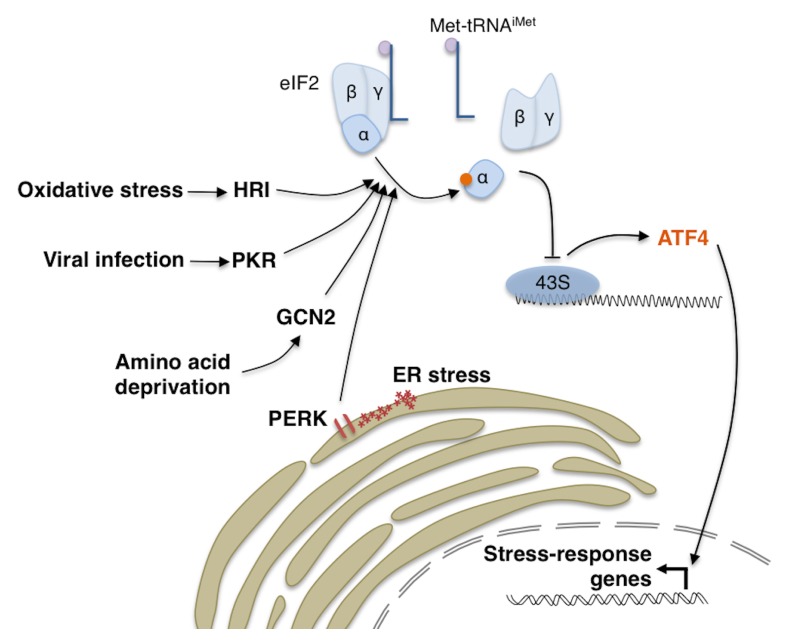

Cells are equipped with a variety of stress response mechanisms that allow them to maintain cellular function when faced with external or physiological stress. Among these mechanisms is the Integrated Stress Response (ISR), which is a signaling pathway initiated by stress-activated kinases that phosphorylate the α subunit of the translational initiation factor eIF2 (1, 2). The term “Integrated Stress Response” is derived from the fact that a diverse array of stresses result in the phosphorylation of eIF2α, and they are integrated into a common downstream signaling pathway. There are multiple stress-activated eIF2α kinases in metazoans: PERK, which is activated by misfolded peptides in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER); GCN2, which is activated under conditions of amino acid deprivation; HRI, which is activated in response to oxidative stress and; PKR, which is activated in response to stress imposed by certain viral infection (Fig. 1). As we will detail below, the ISR pathway utilizes dual nodes of translational inhibition, alongside with transcriptional induction of stress response genes. Here, we will discuss the effect and timing of each node of translation inhibition, and attempt to provide insights into the paradoxical synthesis of stress response proteins under conditions of translational inhibition.

Fig. 1.

The Integrated Stress Response. There are four known stress-responsive eIF2α kinases that can impact global translation: PERK, GCN2, PKR and HRI. Phosphorylation of eIF2α results in the disassembly of the eIF2 complex, and thus reduced availability of initiator methionine (Met-tRNAiMet). While this attenuates translation of most transcripts, a small subset of stress-responsive transcripts such as ATF4 is paradoxically synthesized. ATF4 subsequently induces the transcription of various stress response genes.

THE FIRST NODE OF TRANSLATIONAL ATTENUATION IN THE ISR

The normal role of eIF2 is to deliver initiator methionyl tRNA (Met-tRNAiMet) to the 40S subunit of the ribosome so that the resulting 43S complex can initiate translation (3) (Fig. 1). eIF2 is thought to play an essential role in most mRNA translation, although there are now reports of a very small number of proteins that begin their synthesis with non-methionine residues (4–7), and therefore might not require eIF2 for translation. There are also emerging reports of factors that can deliver Met-tRNAiMet to ribosomes independently of eIF2 (8–10), although such factors may have selective roles, thus limiting the affected mRNAs to a small number. On the other hand, the important role of eIF2 in general translation is reflected by the fact that stress-induced phospho-inhibition of eIF2α results in a significant attenuation of general mRNA translation (11–13). The detailed mechanism by which eIF2α phosphorylation inhibits its normal function has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (3). In brief, the phosphorylated form of eIF2α engages in a non-productive protein complex with its guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B, thereby reducing the ability of cells to recycle eIF2 and deliver Met-tRNAiMet to ribosomes (Fig. 1). This translational attenuation mechanism is thought to help cells recover from stress by reducing the burden on the cellular protein folding system and conserving limited amino acid pools.

This first node of translational inhibition associated with eIF2α phosphorylation is only temporary. The transcriptional and translational response to stress ultimately induces the expression of GADD34, a regulatory subunit of the phosphatase that dephosphorylates eIF2α, resulting in the alleviation of translation attenuation imposed by phospho-eIF2α (14–17). Thus, under experimental conditions, mRNA translation rate recovers within hours of ISR activation, allowing stress response transcripts to be expressed.

eIF2α PHOSPHORYLATION INDUCIBLE TRANSCRIPTS

Cellular response to eIF2α phosphorylation does not merely end with translational attenuation. A small number of specific transcripts remain uninhibited, and their translation is even specifically stimulated under these conditions (11, 18–22). In this category are transcription factors ATF4, ATF5, CHOP, and their yeast equivalent GCN4. Also included in this group is GADD34, the above mentioned phosphatase subunit that stimulates eIF2α dephosphorylation as part of a negative feedback loop (16, 17, 22, 23). Other transcripts that selectively enhance their translation in response to eIF2 phosphorylation, but remain poorly characterized in terms of their roles in ISR include SLC35A4, C19orf48, EPRS and IBTKa (22, 24, 25).

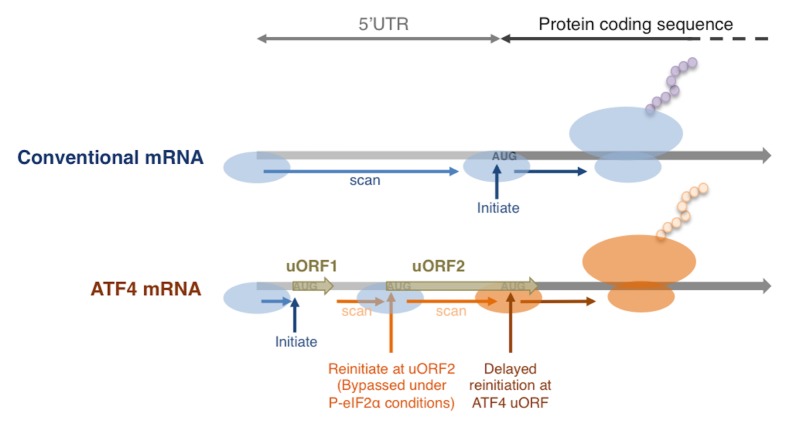

A common feature among these transcripts is the presence of small upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs) in their 5’ UTRs (Fig. 2). There are currently two different proposed mechanisms associated with the paradoxical induction of uORF containing transcript translation. One of those now referred to as delayed reinitiation was initially characterized in yeast GCN4, and its mammalian analogs ATF4 and ATF5. These transcripts contain at least two uORFs in their 5′UTR, with the last uORF overlapping with the main ORF in a different reading frame. The detailed mechanism by which these uORFs enhance the main ORF translation has been reviewed extensively elsewhere (2, 26), and can be briefly summarized as follows: These transcripts load the 43S ribosome complex at the 5′ cap, and from here, the ribosome scans toward the 3′ in search for ORFs (Fig. 2). Once an AUG codon is identified, the ribosome consumes its Met-tRNAiMet to initiate peptide synthesis. After uORF1 translation is completed, the ribosome continues to scan the mRNA but without a Met-tRNAiMet. If re-charging of Met-tRNAiMet is efficient, the ribosome will initiate the translation at uORF2. Only when the re-charging of Met-tRNAiMet is delayed, as in cases where eIF2 is inhibited by phosphorylation, some scanning ribosomes will bypass the last uORF without translation initiation. A belated acquisition of Met-tRNAiMet after the ribosome has passed the AUG of the last uORF, but before the main ORF AUG, would allow the main ORF to be translated. While this example details the mechanism of translation reinitiation on 5′UTRs containing only 2 uORFs, this mechanism has been demonstrated for transcripts with up to 4 uORFs, such as in yeast GCN4 and mammalian ATF4 (18, 27).

Fig. 2.

Delayed translational reinitiation under phospho-eIF2α conditions. The schematic shows a comparison between the translation of conventional mRNA and stress responsive mRNAs with multiple uORFs in their 5′UTRs such as ATF4. The presence of multiple uORFs result in phospho-eIF2α sensitive translation of the ATF4 ORF by delayed translation reinitiation. See main text for more details.

Many of the more recently identified eIF2 phosphorylation resistant transcripts have uORFs that do not overlap with the main ORF, and therefore, the delayed reinitiation mechanism that was extensively characterized for GCN4 and ATF4 are not applicable to those transcripts. Instead, a different mechanism has been proposed for the translational induction of GADD34 and CHOP (20, 23): For example, GADD34 has two uORFs that play regulatory roles. uORF1 of GADD34 has a poor nucleotide context surrounding the start codon, and ribosomes frequently bypass uORF1 without translation. The second uORF is, on the other hand, efficiently translated. This interferes with the main ORF translation as they consume the Met-tRNAiMet associated with eIF2, and also because the uORF2 sequence makes translational termination less efficient in the scanning ribosome (23). The net result is the suppression of GADD34 expression in unstressed cells. Through an as yet poorly understood molecular mechanism, eIF2α phosphorylation causes the ribosomes to bypass uORF2 translation, allowing the main ORF to be recognized and translated. Whether eIF2 phosphorylation directly affects the uORF2 start codon recognition, or whether the effect is indirect remains unclear.

EVIDENCE FOR A SECOND NODE OF TRANSLATIONAL INHIBITION IN ISR

Initial studies on the effect of eIF2α phosphorylation demonstrated that reversing phosphorylation almost entirely restores overall mRNA translation as assessed by 35S-methionine incorporation into nascent peptides of stressed cells (12, 13). This has led to the interpretation that there is only a single node of translational inhibition associated with the ISR. However, a number of studies have emerged in recent years that are gradually changing this view. One of those is a study where the translation rate of a number of specific mRNAs, as opposed to overall mRNA translation, were examined. The study found that while some mRNAs recover in their translation with the GADD34-mediated restoration of eIF2 function, other mRNAs continue to be inhibited in their translation (28). That study also reported that Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) is somehow inactivated by ER stress, which may account for this second node of translational inhibition.

mTOR itself regulates mRNA translation in part through the direct phospho-inactivation of the eIF4E-binding proteins, 4E-BPs (29–31). In its dephosphorylated state, 4E-BP serves as an inhibitor of cap-dependent translation, as it efficiently binds and inhibits eIF4E, the translational initiation factor whose normal function is to bind to the 5′-cap and load the 43S ribosome complex to most cellular mRNAs. Thus, mTOR inactivation in response to ER stress results in active 4E-BP, which in turn strongly inhibits eIF4E-mediated translational initiation. This correlates with the specific inhibition of mRNA translation (28).

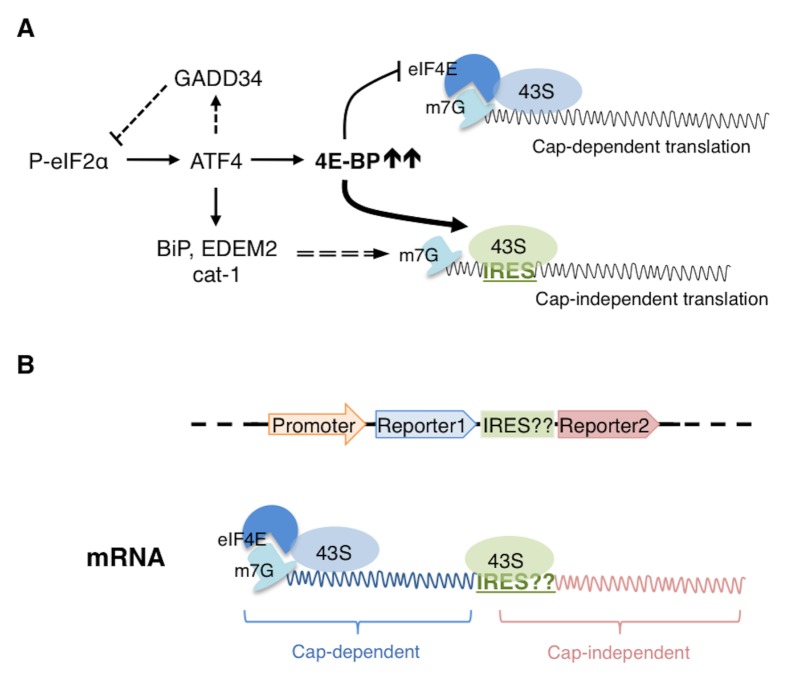

In addition to this post-translational regulatory mechanism, 4E-BP is also under transcriptional regulation. One of the factors that can induce 4E-BP transcription is ATF4, which lies downstream of eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 3A). The initial evidence of the ATF4-mediated 4E-BP regulation came from the studies of mouse beta-islet cells challenged with ER stress causing chemicals (32). That study specifically found that 4E-BP1 to be an ATF4 target, and that deletion of 4E-BP1 makes beta-islet cells more vulnerable to ER stress. A more recent study by our group found that Drosophila 4E-BP is a direct transcription target of ATF4 in response to amino acid deprivation or ER stress (33). Our study showed that the intronic region of Drosophila 4E-BP contains a regulatory element with multiple ATF4 binding sites, which are functionally important in vivo (33). Previous studies had found that 4E-BP contributes to lifespan extension in flies reared with limited yeast content in the food. Consistent with the idea that GCN2 mediates 4E-BP induction under those conditions, GCN2 mutants have reduced lifespans specifically in flies reared with reduced yeast content in the diet (33).

Fig. 3.

4E-BP mediated Cap-independent translation. (A) Translation attenuation by phospho-eIF2α is relieved by a feedback loop involving an eIF2α phosphatase regulatory subunit, GADD34. However, further translation inhibition is imposed by 4E-BP, an ATF4 target. 4E-BP sequesters eIF4E, which is the m7G caprecognition protein. Cap recognition by eIF4E is required for the efficient recruitment of the 43S subunit and thus in the presence of 4E-BP, cap-dependent translation is negatively affected. Under such conditions however, transcripts with IRESes in their 5′UTRs are able to recruit 43S independent of cap-recognition and are thus translated in cap-independent manner. The 5′UTRs of several stress response transcripts, including BiP, EDEM2 and cat-1 have been shown to have IRES elements. (B) The schematic on top shows the arrangement of the elements of a bicistronic construct to test the potential IRES activity of a given 5′UTR (indicated as ‘IRES??’). Expression of this construct in cells results in an mRNA that can recruit 43S in a cap-dependent way, leading to translation of reporter1. If the given 5′UTR has IRES activity, then it can independently recruit 43S for the translation of reporter2. Thus, if expression of both reporters were detected, it would indicate that the given 5′UTR likely has IRES activity.

EXPRESSION OF STRESS RESPONSE GENES BY eIF4E-INDEPENDENT MECHANISMS

As most cellular transcripts require eIF4E for translation initiation, it follows that 4E-BP would presumably inhibit mRNA translation indiscriminately. However, several studies indicate the effect of 4E-BP on mRNA translation is more selective. Researchers established this by analyzing the profile of mRNA translation in cells devoid of 4E-BP family of proteins through ribosome profiling. They found that 4E-BP has differential effects on the translation of individual mRNAs, i.e., there are transcripts that are more readily inhibited by 4E-BP as well as those that are resistant (34, 35). These studies raised an important question: How can certain transcripts bypass translational inhibition by 4E-BP?

Since 4E-BP is an inhibitor of eIF4E, mRNAs that are able to undergo translation without eIF4E could evade suppression by 4E-BP. One such mechanism is through the presence of Internal Ribosome Entry Sites (IRES) in the 5′UTRs of such mRNAs (Fig. 3A). IRES elements were first found in enteroviral and cardioviral transcripts, which lack 5′ cap structures (36, 37). In these 5′ cap lacking mRNAs, IRES elements can recruit ribosomes for translation. This alternate method of recruitment is strategically important for the virus since infection can specifically shut down cap-dependent translation by triggering the cleavage of eIF4G, which is a member of the cap-binding protein complex. Such shut down of cap-dependent translation allows for the viral transcripts to commandeer cellular ribosomes for viral mRNA translation (38). Although first characterized in viral RNAs, a number of cellular transcripts reportedly contain IRES elements. Included in this group are mRNAs of apoptosis regulators. Perhaps because these factors must be expressed even when cap-dependent translation is shut down, anti-apoptotic human XIAP as well as the pro-apoptotic Drosophila reaper mRNA contain IRES and can be expressed in cells devoid of eIF4E (39, 40). A number of other stress response transcripts that are co-expressed with 4E-BP have been found to contain IRES elements. Those associated with ISR will be described in more detail in the next section.

In addition to IRES-mediated translation, a number of other eIF4E-independent translational initiation mechanisms have been uncovered recently. Recent studies have found alternate 5′cap binding proteins, such as eIF3D. While there is no sequence homology with eIF4E, the crystal structure of eIF3D shows a cap-binding domain that is structurally similar to eIF4E. This domain architecture allows eIF3D to mediate the translation of c-Jun in a 5′ cap dependent, but eIF4E-independent manner (41). A second example of eIF4E-independent translation is mediated by N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, a reversible base modification that occurs in mRNAs. Diverse functions of m6A modifications have been identified, but when they occur in the 5′ UTRs in mRNAs, those mRNAs are able to undergo eIF4E-independent translation (42, 43). Specifically, the modified base recruits an alternative translational initiation factor eIF3 to load ribosomes to mRNAs. Transcripts that are translated through this latter mechanism include those involved in UV irradiation response or heat shock proteins, which need to be expressed in stress conditions where cap-dependent translation is shut down. Lastly, cap-independent translation can also be mediated by DAP5, a member of the translational initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) family. DAP5 itself is proteolytically activated by caspases in apoptotic cells where cap-dependent translation can be shut down (44). Upon activation, DAP5 promotes the rate of cap-independent translation of a number of stress responsive and apoptotic genes and cell cycle regulators such as c-Myc, Bcl-2, CDK1, Apaf-1, XIAP and c-IAP1 (45–50).

As indicated in the examples above, many of the cellular transcripts associated with eIF4E-independent translation encode stress-response proteins. This is perhaps not so surprising given that many cellular stresses, ranging from heat shock to viral infection, lead to a shut down or attenuation of cap-dependent translation. Such conditions also require the expression of stress response proteins for the cells to recover, and to ensure their efficient expression, the encoding transcripts have evolved mechanisms to initiate alternative modes of translational initiation.

ISR TRANSCRIPTS THAT UNDERGO IRES-MEDIATED TRANSLATION

The dual nodes of translational inhibition associated with ISR, i.e., phospho-eIF2α due to stress-activated kinases and 4E-BP induced by ATF4, pose an important conceptual question: If ISR activates a transcriptional response program mediated by ATF4 and other factors, how are such stress response transcripts translated in the presence of translational inhibitors? Translational inhibition by eIF2α phosphorylation may not pose a long-term impediment to stress response gene expression, since it is dephosphorylated once the negative feedback loop induces GADD34 expression (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, there are no known negative feedback loops that can reverse 4E-BP activation during ISR. Yet, the sustained expression of stress responsive genes suggests that stress response transcripts may still be translated efficiently in the presence of 4E-BP, likely by eIF4E-independent mechanisms.

Perhaps one of the best-characterized ER stress response gene is the ER chaperone BiP, which is the major HSP70-class chaperone in the ER that helps to fold nascent and unfolded peptides. It is also well known that BiP is transcriptionally induced by ER stress response pathways in diverse organisms, ranging from S. cerevisiae, Drosophila to mammals (51–53). As ER stress also induces 4E-BP through ATF4, one may question whether BiP translation occurs efficiently under these conditions. But even before 4E-BP was recognized as an ER stress responsive translational inhibitor, BiP had been recognized for having IRES in its 5′UTR. The initial clue came from the observation that BiP expression increased in poliovirus-infected cells, where cap-dependent translation is shut down (54). A subsequent study used the so-called bicistronic assay where the IRES activity of the 5′UTR of interest is assessed by placing it in between two reporter ORFs (‘cistrons’) (Fig. 3B). As the ribosomes dissociate from the mRNAs after encountering the stop codon of the first cistron, the second reporter does not get translated under normal conditions. However, the authors found that the 2nd reporter is translated if the BiP 5′UTR sequence precedes the 2nd reporter, indicative of IRES activity (55). A recent study by our group has examined the properties of Drosophila BiP translation to also indicate the presence of IRES. The study found that 4E-BP overexpression, while effective in suppressing the translation of most cellular transcripts, was less effective in inhibiting BiP expression. The 5′UTRs of specific BiP isoforms also score positive in the bicistronic assay (33). These observations indicate that the IRES-activity of BiP 5′UTR is evolutionarily conserved.

An independent series of studies in the early 2000s associated GCN2-mediated ISR activation with IRES-mediated mRNA translation, even though 4E-BP had not yet been recognized as a component of the ISR signaling at the time. One research group specifically investigated how GCN2 mediates the amino acid starvation response to induce the transcription of amino acid transporters such as cat-1. These researchers found that the cat-1 5′UTR scores positive in the bicistronic assay indicative of IRES activity, and its translation is stimulated in response to eIF2α phosphorylation (56, 57). Perhaps those results were received with intrigue at that time, as the observations were inconsistent with the fact that both cap-dependent and independent translation require eIF2 to load Met-tRNAiMet to ribosomes. In light of recent studies showing 4E-BP to be activated downstream of eIF2α phosphorylation, it is now possible to make sense of those past results. We can now hypothesize that though 4E-BP inhibits cap-dependent translation, such inhibition may allow more ribosomes to engage in cap-independent translation of essential stress response transcripts such as BiP and cat-1.

A more recent study has examined the possible presence of IRES elements amongst other ER stress response transcripts (33). The bicistronic assay results indicate that some, but not all, factors involved in ER stress response score positive in this IRES assay. Aside from BiP, EDEM2, the ER-associated degradation factor that helps to degrade misfolded proteins from the ER, has a 5′UTR with IRES activity. However, transcription factors such as ATF4 and XBP1 did not score positive in the IRES assay (33). The latter result is consistent with the detailed characterization in yeast that ribosomes load to the 5′ cap of GCN4 only, and there is no sequence specific IRES activity in its 5′UTR (58). Thus, IRES element may aid in the expression of some stress response genes, but is not a universal requirement. Perhaps other transcripts utilize alternative cap-independent translation mechanisms introduced above, while other transcripts reduce their translation rate upon ISR activation. It also appears likely that reduction of translation rate of other transcripts may be mechanistically required for driving cap-independent translation of stress response transcripts, which may otherwise not be able to efficiently recruit ribosomal components.

THE TIMING OF TRANSLATIONAL INHIBITION IN ISR

Independent studies have examined the temporal spread of translation inhibition by 4E-BP during ISR activation and have reported some conflicting results. In one study, the authors have chosen a time point where they observe maximal effect of eIF2α phosphorylation, and report that at this early time point, IRES containing transcripts reduce their translation rate (22). This is certainly inconsistent with the observations from other studies where IRES containing transcripts were found to increase their expression during ISR activation (56, 57), or in response to viral infection (54, 55). Based on what we now know, the different outcomes are likely due to the selection of different time points after ISR for each study. An earlier time point after stress application would result in eIF2α phosphorylation, but not yet the induction of 4E-BP. On the other hand, a later time point would have 4E-BP fully exerting translation inhibition, while eIF2α phosphorylation has been reversed by GADD34 induction. The net effect would be shift towards cap-independent translation as a delayed response to ISR activation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a systematic analysis to identify all IRES-containing transcripts associated with ISR, and therefore, the full extent of IRES-mediated translation and their impact in stress resistance remains unexplored. In addition, the possible involvement of other eIF4E-independent mRNA translation, such as those initiated by eIF3D, DAP5 and m6A modification remain untested. Thus, the examples of these unconventional 5′UTRs in stress response gene translation is likely to grow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant (R01 EY020866) to H.D.R. and the American Heart Association fellowship (17POST33420032) to D.V.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to hemeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young SK, Wek RC. Upstream open reading frames differentially regulate gene-specific translation in the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16927–16935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.733899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang KJ, Wang CC. Translation initiation from a naturally occurring non-AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13778–13785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starck SR, Jiang V, Pavon-Eternod M, Prasad S, McCarthy B, Pan T, Shastri N. Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science. 2012;336:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1220270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jedrychowski MP, Wrann CD, Paulo JA, et al. Detection and quantitation of circulating human irisin by tandem mass specrometry. Cell Metab. 2015;22:734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starck SR, Tsai JC, Chen K, et al. Translation from the 5′ untranslated regions shapes the integrated stress response. Science. 2016;351:aad3867. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dmitriev SE, Terenin IM, Andreev DE, et al. GTP-independent tRNA delivery to the ribosomal P-site by a novel eukaryotic translation factor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26779–26787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holcik M. Could the eIF2a-independent translation be the achilles heel of cancer? Front Oncol. 2015;5:264. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisser M, Schafer T, Leibundgut M, Bohringer D, Aylett CHS, Ban N. Structural and functional insights into human re-initiation complexes. Mol Cell. 2017;67:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dever TE, Feng L, Wek RC, Cigan AM, Donahue TF, Hinnebusch AG. Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2 alpha by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene-specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell. 1992;68:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90193-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Vattem KM, Sood R, et al. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7499–7509. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.12.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Jungreis R, Harding HP, Ron D. Stress-induced gene expression requires programmed recovery from translational repression. EMBO J. 2003;22:1180–1187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, et al. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YY, Cevallos RC, Jan E. An upstream open reading frame regulates translation of GADD34 during cellular stresses that induce eIF2alpha phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6661–6673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806735200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malzer E, Szajewska-Skuta M, Dalton LE, et al. Coordinate regulation of eIF2alpha phosphorylation by PP1R15 and GCN2 is required during Drosophila development. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:1406–1415. doi: 10.1242/jcs.117614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, et al. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou D, Palam LR, Jiang L, Narasimhan J, Staschke KA, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 directs ATF5 translational control in response to diverse stress conditions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7064–7073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palam LR, Baird TD, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10939–10949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baird TD, Palam LR, Fusakio ME, et al. Selective mRNA translation during eIF2 phosphorylation induces expression of IBTKalpha. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:1686–1697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-02-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreev DE, O’Connor PB, Fahey C, et al. Translation of 5′ leaders is pervasive in genes resistant to eIF2 repression. eLife. 2015;4:e03971. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young SK, Willy JA, Wu C, Sachs MS, Wek RC. Ribosome reinitiation directs gene-specific translation and regulates the integrated stress response. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:28257–28271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.693184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young SK, Baird TD, Wek RC. Translation regulation of the glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase gene EPRS through bypass of upstream open reading frames with noncanonical initiation codons. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:10824–10835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willy JA, Young SK, Mosley AL, et al. Function of inhibitor of brutons tyrosine kinase isoform a (IBTKa) in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis links autophagy and the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:14050–14065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.799304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinnebusch AG, Ivanov IP, Sonenberg N. Translational control by 5′-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science. 2016;352:1413–1416. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinnebusch AG. Evidence for translational regulation of the activator of general amino acid control in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:6442–6446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preston AM, Hendershot LM. Examination of a second node of translational control in the unfolded protein response. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4253–4261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunn GJ, Fadden P, Haystead TA, Lawrence JC., Jr The mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylates sites having a (Ser/Thr)-Pro motif and is activated by antibodies to a region near its COOH terminus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32547–32550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burnett PE, Barrow RK, Cohen NA, Snyder SH, Sabatini DM. RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators P70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1432–1437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fadden P, Haystead TA, Lawrence JC., Jr Identification of phosphorylation sites in the translational regulator, PHAS-I, that are controlled by insulin and rapamycin in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10240–10247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamaguchi S, Ishihara H, Yamada T, et al. ATF4-mediated induction of 4E-BP1 contributes to pancreatic beta cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2008;7:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang MJ, Vasudevan D, Kang K, et al. 4E-BP is a target of the GCN2-ATF4 pathway during Drosophila development and aging. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:115–129. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoreen CC, Chantranupong L, Keys HR, Wang T, Gray NS, Sabatini DM. A unifying model for mTORC1-mediated regulation of mRNA translation. Nature. 2012;485:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012;485:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature. 1988;334:320–325. doi: 10.1038/334320a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jang SK, Krausslich HG, Nicklin MJ, Duke GM, Palmenberg AC, Wimmer E. A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J Virol. 1988;62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2636-2643.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etchison D, Milburn SC, Edery I, Sonenberg N, Hershey JW. Inhibition of HeLa cell protein synthesis following poliovirus infection correlates with the proteolysis of a 200,000-dalton polypeptide associated with eucaryotic initiation factor 3 and a cap binding protein complex. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14806–14810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez G, Vazquez-Pianzola P, Sierra JM, Rivera-Pomar R. Internal ribosome entry site drives cap-independent translation of reaper and heat shock protein 70 mRNAs in Drosophila embryos. RNA. 2004;10:1783–1797. doi: 10.1261/rna.7154104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riley A, Jordan LE, Holcik M. Distinct 5′ UTRs regulate XIAP expression under normal growth conditions and during cellular stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4665–4674. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee AS, Kranzusch PJ, Doudna JA, Cate JH. eIF3d is an mRNA cap-binding protein that is required for specialized translation initiation. Nature. 2016;536:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature18954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, et al. 5′ UTR m(6)A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, Zhang X, Jaffrey SR, Qian SB. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henis-Korenblit S, Strumpf NL, Goldstaub D, Kimchi A. A novel form of DAP5 protein accumulates in apoptotic cells as a result of caspase cleavage and internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:496–506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.2.496-506.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marash L, Liberman N, Henis-Korenblit S, et al. DAP5 promotes cap-independent translation of Bcl-2 and CDK1 to facilitate cell survival during mitosis. Mol Cell. 2008;30:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bukhari SIA, Truesdell SS, Lee S, et al. A specialized mechanism of translation mediated by FXR1a-associated microRNP in cellular quiescence. Mol Cell. 2016;61:760–773. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henis-Korenblit S, Shani G, Sines T, Marash L, Shohat G, Kimchi A. The caspase-cleaved DAP5 protein supports internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of death proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5400–5405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082102499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nevins TA, Harder ZM, Korneluk RG, Holcik M. Distinct regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation following cellular stress is mediated by apoptotic fragments of eIF4G translation initiation factor family members eIF4G1 and p97/DAP5/NAT1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3572–3579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warnakulasuriyarachchi D, Cerquozzi S, Cheung HH, Holcik M. Translational induction of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein HIAP2 during endoplasmic reticulum stress attenuates cell death and is mediated via an inducible internal ribosome entry site element. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17148–17157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis SM, Cerquozzi S, Graber TE, Ungureanu NH, Andrews M, Holcik M. The eIF4G homolog DAP5/p97 supports the translation of select mRNAs during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:168–178. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozutsumi Y, Segal M, Normington K, Gething M-J, Sambrook J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose-regulated proteins. Nature. 1988;332:462–464. doi: 10.1038/332462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryoo HD, Domingos PM, Kang MJ, Steller H. Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. EMBO J. 2007;26:242–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarnow P. Translation of glucose-regulated protein 78/immunoglobulin heavy-chain binding protein mRNA is increased in poliovirus-infected cells at a time when cap-dependent translation of cellular mRNA is inhibited. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5795–5799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Macejak DG, Sarnow P. Internal initiation of translation mediated by the 5′ leader of a cellular mRNA. Nature. 1991;353:90–94. doi: 10.1038/353090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez J, Yaman I, Merrick WC, et al. Regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation by eukaryotic initiation factor-2alpha phosphorylation and translation of a small upstream open reading frame. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2050–2058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez J, Bode B, Koromilas A, et al. Translation mediated by the internal ribosome entry site of the cat-1 mRNA is regulated by glucose availability in a PERK kinase-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11780–11787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hinnebusch AG, Jackson BM, Mueller PP. Evidence for regulation of reinitiation in translational control of GCN4 mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7279–7283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]