Abstract

Background

As perinatal HIV-infected youth become sexually active, the potential for onward transmission becomes an increasing concern. In other populations, intimate partner violence (IPV) is a risk factor for HIV acquisition. We build on this critical work by studying the role of IPV in facilitating onward transmission among HIV-infected youth – an important step towards effective intervention.

Setting

Soweto, South Africa.

Methods

Self-report surveys were completed by 129 perinatal HIV-infected female youth (aged 13–24). We calculated the IPV prevalence, and used logistic models to capture the association between IPV and health outcomes known to facilitate onward HIV transmission (e.g., risky sex, poor medication adherence, depression, substance abuse).

Results

A fifth of perinatal HIV-infected participants reported physical and/or sexual IPV in the past year; a third reported lifetime IPV. Childhood adversity was common and positively associated with IPV. Past-year physical and/or sexual IPV was positively correlated with high risk sex (OR=8.96; 95% CI 2.78–28.90), pregnancy (OR=6.56; 95% CI 1.91–22.54), poor medication adherence to antiretroviral therapy (OR=5.37; 95% CI 1.37–21.08), depression (OR 4.25; 95% CI 1.64–11.00) and substance abuse (OR 4.11; 95% CI 1.42–11.86 respectively). Neither past-year nor lifetime IPV was associated with viral load or HIV status disclosure to a partner.

Conclusion

We find that IPV may increase risk for onward HIV transmission in perinatal HIV-infected youth by both increasing engagement in risky sexual behaviors and by lowering medication adherence. HIV clinics should consider integrating primary IPV prevention interventions, instituting routine IPV screening, and collocating services for victims of violence.

Keywords: perinatal infection, youth, intimate partner violence, sexual risk, adherence

Introduction

Globally, almost a third of ever-partnered women will experience physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) over their lifetime1. IPV has a negative impact on health, including injury, substance abuse, depression, unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and homicide2. Importantly, IPV is linked to HIV risk both through direct transmission and through an indirect effect on subsequent high risk sexual behavior3–5. In a recent longitudinal study of young South African women, for example, those who experienced IPV were one and a half times more likely to acquire HIV6.

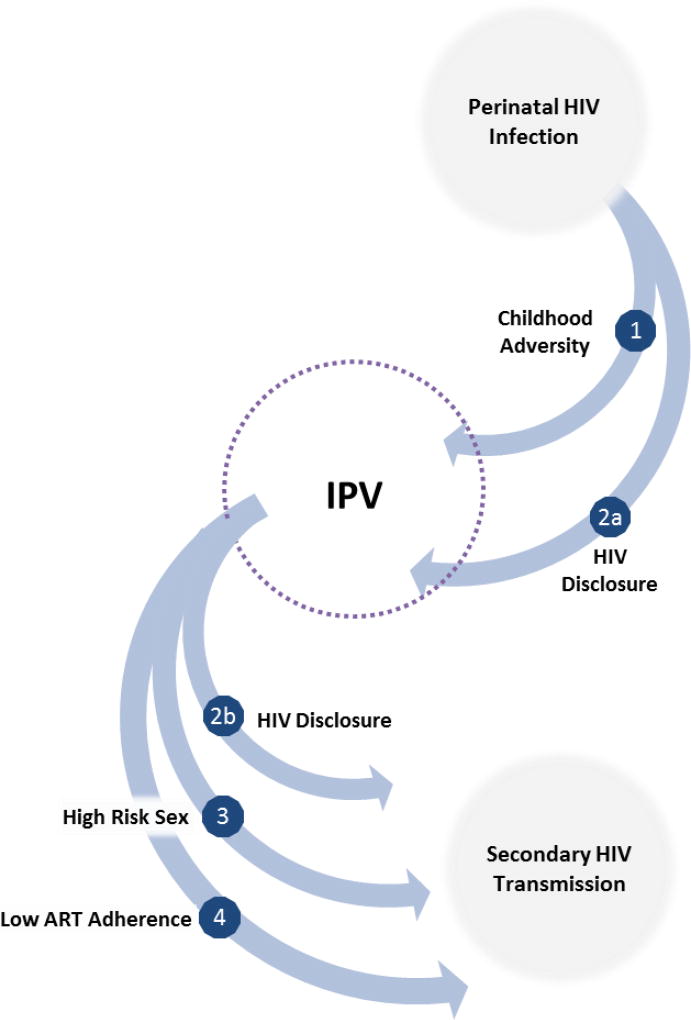

Why then might we want to study IPV among those already infected with HIV, including youth perinatal HIV-infected with HIV (PHIV)? One reason is that PHIV may experience a disproportionate burden of IPV. In part, this may be because HIV disclosure can trigger violent reactions from romantic partners (represented by pathway 2a in Figure 1)7–9. There may also be secondary pathways between HIV and IPV that are mediated by childhood adversity (pathway 1). Research shows that HIV-infected children disproportionately experience physical and sexual abuse10,11; and are more likely to live with an ill parent and/or experience parental death. There is evidence, though not from this population, that such childhood adversities can lead to greater IPV victimization during adolescence12.

Figure 1.

Potential pathways from perinatal HIV-infection to IPV and secondary HIV transmission (adapted from7)

There is a second important reason to study IPV among this group: IPV may facilitate onward HIV transmission among PHIV youth. A causal relationship between IPV and sexual risk taking is well documented (pathway 3)13–15, though again such literature has not been extended specifically to PHIV. Such risk taking is often fuelled, at least in part, by heightened levels of depression and substance abuse among victims2,16,17. Fear also plays a prominent role. Victims fear a violent reaction if they decline sex or suggest using a condom18. For HIV-positive victims, there is also a fear of inadvertently disclosing their HIV status by insisting on condom use19. Thus, victims are less able to negotiate condom use, sexual initiation, and sexual exclusivity4,13,15.

HIV disclosure can be one way to encourage safer sexual practices, but IPV complicates this mechanism. As mentioned above, disclosure can trigger violence. Moreover, violence or the threat of violence can discourage disclosure (pathway 2b)8,20–22. This means sexual partners are unable to make informed choices and may not take precautions to prevent transmission.

Finally, IPV may heighten risk of onward transmission by interfering with HIV treatment necessary for viral suppression (pathway 4)23. Among adults, there is ample evidence that IPV impedes adherence to lifesaving antiretroviral therapy (ART): a recent meta-analysis found women experiencing IPV were about half as likely to be adherent or achieve viral suppression24. Youth already demonstrate poor adherence as compared with other age groups25. If adherence is lower still among those experiencing IPV, this could have meaningful implications for both disease progression and HIV transmission.

Approximately four million youth aged 15–24 are now living with HIV globally26. A substantial proportion acquired HIV from their mothers (40% among 15–19 year olds)27. The widespread introduction of ART over the past decade has contributed to the survival and rapid growth of this population. As PHIV become sexually active, however, the potential for onward transmission becomes an increasing concern28. Understanding the role of IPV in this process is an important step towards effective intervention. This is particularly critical in South Africa, where epidemics of HIV and violence coexist29. Approximately 7% of adolescents aged 15–24 live with HIV30. Many more are in violent relationships: 23% of girls and young women (aged 15 to 26 years) in the Eastern Cape and 37% of those (aged 15 to 19) in Johannesburg reported past-year IPV6,31.

Methods

This exploratory study was undertaken to examine the prevalence, predictors and health impact of IPV among a sample of PHIV youth in South Africa. We hypothesized that IPV would be common among perinatal HIV-infected youth, and would adversely impact clinical, behavioral and mental health outcomes associated with onward HIV transmission.

Study Design and Participants

This study collected data from 250 youth recruited from the Paediatric Wellness Clinic, part of the Paediatric HIV Research Unit in Soweto, South Africa. To be eligible, participants had to (1) have documented HIV infection before age 10; (2) be aware of their HIV diagnosis; (3) be age 13–24; and (4) be able to read English. Participants were excluded for acute psychiatric illness and cognitive impairment. Surveys were preprogrammed in English on tablet computers. Each participant completed the survey themselves in a private conference room at the clinic. Nurses conducted a chart review to abstract clinical data. The current analyses focus on the 129 female adolescents with complete data on IPV (this excludes seven females); males were not asked about IPV. The study had ethical approval from both Stony Brook University in the United States and the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa.

Measures

Intimate partner violence

Questions were adapted from the WHO Violence Against Women Instrument32. Female participants were asked if their current boyfriend, husband or any other partner ever slapped them or threw something that could hurt; pushed or shoved them; hit them with his first or something else; kicked, dragged or beat them; choked or burnt them on purpose; or threatened to use or actually used a gun, knife or other weapon against them. Participants reporting any of the above were classified as having experienced lifetime physical IPV; those reporting that it occurred within the past 12 months were additionally classified as having experienced past-year physical IPV. Two more questions focused on sexual IPV and were classified the same way: whether their current boyfriend, husband or any other partner ever physically forced them to have sexual intercourse when they didn’t want to; and whether they ever have sexual intercourse because they were afraid of what their partner might do. Finally, combined measures of physical and/or sexual IPV were created for each time frame.

Childhood adversity

Participants completed the Adverse Childhood Experience - International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ)33. The ACE-IQ covers 13 domains, including abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, parental death, bullying, and exposure to violence outside the home. For each of the 13 domains, we assigned a one if any question was answered affirmatively34. The cumulative score was also categorized into lower (0–3), higher (4–7), and very high (8–13) adversity.

Sexual risk

Participants were asked whether they had ever had sex. If so, they were asked additional questions about past-year experiences adapted from measures in the South Africa Demographic and Health Survey, previously used among youth35. These were used create a dichotomous variable representing high risk sexual behavior, coded one if the participant reported having concurrent partners (two or more in the same month), having three or more partners in the past year, or not using a condom with their most recent partner. These are all behaviors previously shown to increase HIV risk in African settings36,37, and thus engagement in any one of these could potentially jeopardize health. Sexually inexperienced participants, or those not reporting the above risk behaviors in the past year, were coded as zero. Participants also self-reported on whether they currently were or had ever been pregnant. Finally, participants were asked if they currently had a boyfriend or girlfriend.

HIV disclosure

Several questions asked about disclosure to family, peers, boyfriends/girlfriends, and sexual partners. In this study, we report separately on HIV status disclosure to a boyfriend/girlfriend and to the most recent sexual partner; in each case this was coded one if they had disclosed that they were HIV-positive and zero otherwise. Participants were also asked to report on reasons for non-disclosure by selecting options from a predetermined list.

Mental health

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (analyzed using a pre-established cut-point of 20 for moderate to severe depression)38. Problematic substance use was captured with the adolescent self-administered version of the CRAFFT Screening Questionnaire for alcohol and substance abuse39.

Adherence and viral load

Participants who reported currently taking ART were asked about adherence; these questions were adapted from WHO tools40. Participants were considered to have poor adherence if they reported skipping at least one pill in the past week. Viral suppression, abstracted from medical records, was defined as having a viral load of less than 200 copies/ml on their most recent laboratory report41. Sensitivity analyses were done at other cut points (e.g., 400; 20 copies/ml) and results did not change.

Control variables

Additional questions captured age, relationship to caregiver (dichotomized into parent versus non-parent), and wealth. Wealth was a cumulative measure of whether their household owned a TV, radio, car, cell phone, or computer; this was transformed into wealth quintiles for analyses.

Analyses

Analyses focus on 129 female participants; seven additional female participants were excluded from current analyses due to incomplete data on IPV. We use frequencies to describe the sample characteristics, including IPV prevalence. We run two sets of logistic regressions. First, we regress childhood adversity on IPV. Second, we regress IPV on the behavioral and clinical outcomes described above. Models were created separately for past-year and lifetime physical and/or sexual IPV. Neither wealth nor relationship to the caregiver was predictive of health outcomes; age was thus the only control variable retained in the final models. Finally, we re-ran the outcome models restricting the sample to those participants who are currently partnered. All analyses were done in Stata v13.0.

Results

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. Just over half the participants were in mid-adolescence (age 13–16), a quarter in late adolescence (age 17–19), and the remainder were age 20–24. A parent was reported as the primary caregiver by only about half the participants. Almost two fifths (37%) met the criteria for depression and 15% for substance abuse problems.

Table 1.

Prevalence of past-year and lifetime experiences of physical and/or sexual IPV for female PHIV youth, by sociodemographic and health characteristics

| N (%) | Past-Year IPV |

Lifetime IPV |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age group | |||

| Mid-adolescence (13–16) | 74 (57%) | 16% | 28% |

| Late-adolescent (17–19) | 33 (26%) | 15% | 36% |

| Youth (20–24) | 22 (17%) | 32% | 41% |

| Caregiver | |||

| Parent | 71 (55%) | 17% | 28% |

| Other | 58 (45%) | 21% | 38% |

| Wealth | |||

| Bottom two quintiles | 57 (44%) | 18% | 26% |

| Top three quintiles | 63 (66%) | 17% | 37% |

| Adverse childhood experiences | |||

| 0–3 adversities | 12 (9%) | 8% | 8% |

| 4–7 adversities | 45 (35%) | 11% | 20% |

| 8–13 adversities | 72 (56%) | 25% | 44% |

| Health | |||

| High risk sex in past year | |||

| Yes | 21 (16%) | 52% | 71% |

| No | 101 (84%) | 12% | 25% |

| Ever pregnant | |||

| Yes | 13 (10%) | 54% | 100% |

| No | 114 (90%) | 14% | 25% |

| Adherenceǂ | |||

| Poor | 39 (46%) | 31% | 38% |

| Adequate | 42 (54%) | 7% | 21% |

| Viral load | |||

| <200 | 76 (59%) | 16% | 34% |

| >200 | 53 (41%) | 23% | 30% |

| HIV status disclosure to boyfriend/girlfriend | |||

| Yes | 20 (16%) | 20% | 40% |

| No | 109 (84%) | 18% | 31% |

| Depression | |||

| Severe/moderate symptoms | 48 (37%) | 33% | 50% |

| Mild/no symptoms | 76 (63%) | 11% | 21% |

| Alcohol and drug use problems | |||

| Yes | 19 (15%) | 42% | 58% |

| No | 110 (85%) | 15% | 28% |

|

| |||

| Total Sample | 129 (100%) | 19% | 33% |

measured among 85 participants reporting current ART use

All but two were currently on ART (data not in tables), yet just 59% were virally suppressed. While a substantial number of sexually-active youth reported risky behavior, this was offset by the low prevalence of sexual debut (only 36%). This meant that just 16% of the total cohort (sexually active and not) reported high risk sexual behaviors. Despite such, 10% of the cohort had already been pregnant.

Since learning of their own status, only 42% of participants had told someone else that they were HIV-positive. Many reported currently being in a relationship (59%), but few had had ever shared their HIV status with a romantic partner (16% overall; 22% among those with a current partner). Disclosure was higher to sexual partners, but still far from universal: only 47% of those who were sexually active had told their most recent partner that they were HIV-infected. When asked about reasons for non-disclosure, a third cited fear that their sexual partner might physically hurt them (data not shown in tables).

Prevalence and correlates of IPV among perinatal HIV-infected youth

Overall, a third of participating PHIV youth reported ever experiencing physical and/or sexual IPV violence in their lifetime (Table 1). Lifetime physical violence (27%) was more common than sexual violence (17%). Almost a fifth of the participants were victimized by their partner in the past year: 18% experienced physical violence and 4% experienced sexual violence. Sexual and/or physical IPV increased with age (e.g., past year IPV was 32% among youth 20–24 versus 15–16% among younger ages).

Childhood adversity was positively associated with IPV among perinatal HIV-infected youth

On average, participants reported 7.3 childhood adversities. Most participants reported multiple childhood adversities: 35% reported between four and seven adversities and 55% reported eight or more adversities. PHIV youth reporting greater adversity also reported greater IPV. Among those with eight or more childhood adversities, past year and lifetime physical and/or sexual IPV prevalence was 25% and 44% respectively. In comparison, only 8% of participants with three or fewer adversities reported any IPV.

In age-adjusted models, each additional adversity was associated with approximately a 30% increase in the odds of experiencing lifetime (AOR 1.37; 95% CI 1.15–1.63; p=0.000) or past-year physical and/or sexual IPV (AOR 1.30; 95% CI 1.06–1.60; p=0.013). If examined categorically, moving from one adversity category to the next was associated with over three times the odds of experiencing lifetime physical and/or sexual IPV (OR 3.07; 95% CI 1.50–6.28; p=0.002) and twice the odds of past-year physical and/or sexual IPV (AOR 2.23; 95% CI 0.96–5.18; p=0.061).

IPV correlates with behavioral risk among perinatal HIV-infected youth

IPV was associated with high risk sex, pregnancy, depression and substance abuse. Compared to girls who had not experienced past-year IPV, girls with a history of either physical and/or sexual IPV had nine time the odds of having engaged in high risk sexual behaviors in the past year (AOR=8.96; 95% CI 2.78–28.90, Table 2) and almost seven times the odds of pregnancy (AOR=6.56; 95% CI 1.91–22.54). Depression and substance abuse were also elevated in those participants reporting past-year physical and/or sexual IPV (AOR 4.25; 95% CI 1.64–11.00 and AOR 4.11; 95% CI 1.42–11.86 respectively). Modeling lifetime IPV produced similar results (Table 2). Of note, every participant who reported a pregnancy also reported experiencing lifetime IPV.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted associations between physical and/or sexual IPV and transmission risk behaviors among female PHIV youth (n=129)

| Past-Year IPV | Lifetime IPV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value |

| High risk sex in past year | 8.96 | 2.78–28.90 | 0.000 | 9.37 | 2.88–30.51 | 0.000 |

| Ever pregnant | 6.56 | 1.91–22.54 | 0.003 | ǂǂ | ||

| Poor adherenceǂ | 5.37 | 1.37–21.08 | 0.016 | 2.25 | 0.83–6.05 | 0.109 |

| Viral load <200 | 0.711 | 0.28–1.81 | 0.474 | 1.35 | 0.61–2.98 | 0.461 |

| HIV status disclosure to boyfriend/girlfriend | 0.87 | 0.24–3.16 | 0.837 | 1.34 | 0.47–3.82 | 0.580 |

| Depression | 4.25 | 1.64–11.00 | 0.003 | 3.75 | 1.70–8.29 | 0.001 |

| Alcohol and drug use problems | 4.11 | 1.42–11.86 | 0.009 | 3.42 | 1.25–9.35 | 0.017 |

measured among 85 participants reporting current ART use

Cannot be estimated because all youth reporting pregnancy also reported lifetime IPV

Past-year physical and/or sexual IPV also displays a strong relationship with poor medication adherence (OR=5.37; 95% CI 1.37–21.08). However, this relationship did not reach significance in the lifetime IPV model. Neither past-year nor lifetime IPV was associated with viral load. IPV was likewise unrelated to HIV status disclosure.

The above analyses include all girls and young women in our sample, regardless of partnership status. If IPV is a proxy for being partnered, then this approach may artificially inflate some of the above associations. Thus, we re-ran the above models restricting the sample to the 59% of participants who reported that they currently had a boyfriend or girlfriend (see Table 3). While results are qualitatively similar, there is reduction in the magnitude of the associations. For example, past-year IPV was associated with almost six times the odds of engaging in high risk sexual behaviors (AOR 5.55; 95% CI 1.62–19.04) or ever being pregnant (AOR 5.59; 95% CI 1.35–23.17) in the restricted sample; these are each a bit lower than the odds ratios found in the full sample (AOR 8.96 and 6.56 respectively).

Table 3.

Age-adjusted associations between physical and/or sexual IPV and transmission risk behaviors among female PHIV youth with a current partner (n=76)

| Past-Year IPV | Lifetime IPV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value |

| High risk sex in past year | 5.55 | 1.62–19.04 | 0.006 | 3.62 | 1.90–22.97 | 0.003 |

| Ever pregnant | 5.59 | 1.35–23.17 | 0.018 | ǂǂ | ||

| Poor adherenceǂ | 3.13 | 0.82–13.59 | 0.128 | 3.46 | 0.90–13.28 | 0.071 |

| Viral load <200 | 0.85 | 0.29–2.56 | 0.773 | 1.39 | 0.51–3.80 | 0.522 |

| HIV status disclosure to boyfriend/girlfriend | 0.76 | 0.20–2.80 | 0.676 | 1.21 | 0.39–3.73 | 0.743 |

| Depression | 2.61 | 0.91–7.46 | 0.074 | 2.31 | 0.89–5.60 | 0.084 |

| Alcohol and drug use problems | 3.47 | 1.11–10.92 | 0.033 | 3.63 | 1.15–11.41 | 0.028 |

measured among 49 participants reporting current ART use

Cannot be estimated because all youth reporting pregnancy also reported lifetime IPV

Discussion

Intimate partner violence is an established risk factor for HIV acquisition5. To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the confluence of IPV and risk of onward transmission among PHIV. We find that PHIV girls and youth contend with unacceptably high levels of violence: a fifth reported being physically or sexually victimized by their partner in the past year. IPV was much higher still for those girls reporting a heavy burden of childhood adversities, emphasizing the compounding nature of violence and suggesting early intervention is crucial.

Critically, we find that this violence likely serves to perpetuate the cycle of HIV. Girls experiencing IPV were less likely to practice health behaviors that protect against onward transmission or re-infection. Instead, victims were more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior, inconsistently take their HIV medications, and have a substance abuse problem. Moreover, there was a strong association between IPV and pregnancy – another outcome of unprotected sex. In our sample, each young woman who reported a pregnancy also reported experiencing lifetime IPV. Taken together, this suggests that IPV may facilitate onward transmission. Cross-sectional data, however, prohibits inference on the causal link. It is possible that IPV is both a predictor and product of sexual risk and/or pregnancy, or that they have mutual risk factors.

The cross-sectional nature of the data also makes it difficult to interpret the null results around disclosure. Studies in Uganda have found that less than half of perinatal HIV-infected youth tell partners that they are HIV-positive42,43. We found similarly low rates, but did not find a clear relationship between IPV and HIV status disclosure. This may reflect two simultaneous but opposing processes: for some youth, disclosure may trigger IPV (a positive association)8; for other youth, a history of IPV may discourage disclosure (a negative association)8,22. Temporal data is needed to tease out any bidirectional relationships.

Another limitation of this exploratory study was its focus on a small, clinic-based sample. In other studies, IPV has been linked to interruptions in HIV care23. If this is true, PHIV youth with high rates of IPV may be less likely to be captured in our study. This may lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of IPV and/or its association to negative health behaviors. Moreover, almost all participants in our sample were on ART. A US-based study found that IPV influenced viral load only if HIV-positive women were not on ART. There was no impact if women were on ARTs, consistent with our finding23. The fact that our sample was engaged in care and on ART may partially explain why we did not find a relationship between IPV and viral load.

A final limitation to note is that we could not identify whether participants had ever been partnered. Individuals are only at risk for IPV if they have had a partner, and they are also only at risk for sexual outcomes if they have had a partner. Thus, IPV could be acting as a proxy for sexual risk in our full sample. To examine this possibility, we restricted the sample to those participants who were currently partnered, and found similar – though slightly attenuated – associations. The restricted sample, however, excludes girls who may have had a violent partner in the past and ended the relationship (20% of those not in a current relationship reported lifetime IPV). Thus, the true association between IPV and sexual health may lie somewhere in the middle.

These limitations, however, do not take away from finding that IPV is linked to multiple behavioral risks in youth with known HIV infection and could result in onward HIV transmission. Even in an exploratory study, this finding emerges clearly and should serve to stimulate programmatic action and rigorous research.

Implications

Relative to other ages, we have made little progress in lowering HIV incidence among adolescent girls and young women26. The United Nations General Assembly Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS highlights tackling violence against women as a key prevention strategy. However, their focus is on HIV-negative women. Our findings strongly suggest that this strategy should be broadened to explicitly address IPV among PHIV youth with high potential for onward transmission. While our findings are more mixed regarding clinical implications, it is possible that reducing IPV would improve adherence and subsequent disease progression.

Our research points to two main intervention points in the HIV care continuum. First, pediatric HIV providers could integrate services for primary IPV prevention. As hypothesized, PHIV youth had a high burden of childhood adversity, a key driver of later IPV. Pediatric providers are well placed to recognize such and to offer early intervention. Parenting programs, for example, have been shown to reduce child maltreatment and domestic violence44,45. For those who have already been traumatized, linkage to mental health and substance abuse treatment may help mitigate the impact on later IPV exposure46. As patients reach adolescence, clinics could offer HIV-specific prevention education coupled with components designed to prevent IPV exposure47,48. Promising intervention could be adapted for the PHIV audience. For instance, additional components might include how to facilitate safer HIV disclosure and protect against inadvertent disclosure49.

Second, routine screening for IPV among PHIV youth should be a priority. While WHO guidelines don’t recommend universal IPV screening in low and middle income countries, they do suggest selective screening when “assessing conditions that may be caused or complicated by intimate partner violence”50. The guidelines specifically acknowledge the complex issues around HIV, including its impact on disclosure and risk-reduction strategies, and leave the door open for routine testing among HIV-positive patients. Our findings add to growing body of evidence linking IPV to health outcomes among HIV-positive patients24, and lend related support for routine screening. Research has shown that patients react positively to routine IPV screening in HIV counseling sessions51. South African nurses likewise report a strong desire and willingness for IPV training52. Taken together, we believe there is a strong argument for routine screening. Of course, screening is not effective when implemented in isolation; it needs to be followed by engagement in effective intervention53. In our study, past-year IPV was associated with recent adherence; lifetime IPV was not. This suggests that girls and young women may be resilient to the effects of past IPV when it comes to adherence, but are affected by ongoing or recent trauma. Services that help girls and young women exit abusive relationships may yield relatively quick dividends for medication adherence. Services designed to address IPV, mental health, and substance abuse need to be readily available – an admittedly large challenge in settings with limited social services. Collocating services for victims of violence into existing HIV treatment centers may increase availability and uptake. In addition to making referrals54, HIV health providers can play a supportive role by helping patients devise strategies to optimize health and reduce transmission within the context of known IPV.

Finally, structural interventions that address the broader norms influencing IPV should be a high priority. Individually-focused interventions do not address the gendered power dynamics or prevailing social norms in which IPV occurs. Ultimately, any actions directed at PHIV will need to be coupled with broader wider gender-transformative interventions in their community47,48,55.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD083032 and supported by the South African Medical Research Council. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the South African Medical Research Council.

References

- 1.Devries KM, Mak JYT, García-Moreno C, et al. The Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence Against Women. Science. 2013;340(6140):1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1240937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331–1336. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jewkes R, Vundule C, Maforah F, Jordaan E. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52(5):733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettifor AE. Sexual Power and HIV Risk, South Africa-Volume 10, Number 11—November 2004-Emerging Infectious Disease journal-CDC. 2004 doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Violence Against Women and HIV/AIDS: Critical Intersections Intimate Partner Violence and HIV/AIDS. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatcher AM, Woollett N, Pallitto CC, et al. Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(4):299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombini M, James C, Ndwiga C. The risks of partner violence following HIV status disclosure, and health service responses: narratives of women attending reproductive health services in Kenya. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenig LJ, Pals SL, Chandwani S, et al. Sexual transmission risk behavior of adolescents with HIV acquired perinatally or through risky behaviors. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(3):380–390. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f0ccb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez J, Hosek SG, Carleton RA. Screening and assessing violence and mental health disorders in a cohort of inner city HIV-positive youth between 1998–2006. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2009;23(6):469–475. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller E, Breslau J, Chung WJ, Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Kessler RC. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of physical violence in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2011 doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.105429. jech. 2009.105429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker AL. Does Physical Intimate Partner Violence Affect Sexual Health? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2007;8(2):149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35(6):1461–1468. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunkle KL, Decker MR. Gender-based violence and HIV: Reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2013;69(s1):20–26. doi: 10.1111/aji.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai AC, Wolfe WR, Kumbakumba E, et al. Prospective Study of the Mental Health Consequences of Sexual Violence Among Women Living With HIV in Rural Uganda. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2016;31(8):1531–1553. doi: 10.1177/0886260514567966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacPhail C, Campbell C. ‘I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things’:: condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Social science & medicine. 2001;52(11):1613–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busza J, Besana GVR, Mapunda P, Oliveras E. “I have grown up controlling myself a lot.” Fear and misconceptions about sex among adolescents vertically-infected with HIV in Tanzania. Reproductive Health Matters. 2013;21(41):87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41689-0. 5// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gielen A, Campo P, Faden R, Eke A. Women's Disclosure of HIV Status: Experiences of Mistreatment and Violence in an Urban Setting. [1997/07/24];Women & Health. 1997 25(3):19–31. doi: 10.1300/J013v25n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ezechi OC, Gab-Okafor C, Onwujekwe DI, Adu RA, Amadi E, Herbertson E. Intimate partner violence and correlates in pregnant HIV positive Nigerians. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;280(5):745–752. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maman S, Groves AK, Reyes HLM, Moodley D. Diagnosis and disclosure of HIV status: implications for women's risk of physical partner violence in the postpartum period. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2016;72(5):546–551. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siemieniuk RAC, Krentz HB, Miller P, Woodman K, Ko K, Gill MJ. The Clinical Implications of High Rates of Intimate Partner Violence Against HIV-Positive Women. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2013;64(1):32–38. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829bb007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stöckl H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(16):2183–2194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunologic outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in southern Africa. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2009;51(1):65. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199072e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Gap Report. UNAIDS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNAIDS. Get on the Fast-Track — The life-cycle approach to HIV. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowenthal ED, Bakeera-Kitaka S, Marukutira T, Chapman J, Goldrath K, Ferrand RA. Perinatally acquired HIV infection in adolescents from sub-Saharan Africa: a review of emerging challenges. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(7):627–639. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karim QA, Baxter C. The dual burden of gender-based violence and HIV in adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2016;106(12):1151–1153. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106.i12.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuma K, Shisana O, Rehle TM, et al. New insights into HIV epidemic in South Africa: key findings from the National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2016;15(1):67–75. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1153491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decker MR, Peitzmeier S, Olumide A, et al. Prevalence and health impact of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence among female adolescents aged 15–19 years in vulnerable urban environments: a multi-country study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(6):S58–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. [Accessed April 2, 2014];Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/

- 34.World Health Organization. [Accessed April 10, 2014];Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ): Guidance for Analysing ACE-IQ. 2014 http://www.healthinternetwork.com/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/

- 35. [Accessed December 15, 2010];South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2003. 2007 http://www.doh.gov.za/facts/sadhs2003/part1.pdf.

- 36.Chen L, Jha P, Stirling B, et al. Sexual Risk Factors for HIV Infection in Early and Advanced HIV Epidemics in Sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic Overview of 68 Epidemiological Studies. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(10):e1001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weller S, Davis-Beaty K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission (Review) The Cochrane Library. 2007;4:1–24. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical psychology review. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1999;153(6):591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. HIV Testing, Treatment and Adherence: Generic Tools for Operational Research. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Resources and Services Administration. Performance Measure: HIV Viral Load Suppression. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birungi H, Mugisha JF, Obare F, Nyombi JK. Sexual Behavior and Desires Among Adolescents Perinatally Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Uganda: Implications for Programming. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(2):184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.004. 2// [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mbalinda SN, Kiwanuka N, Eriksson LE, Wanyenze RK, Kaye DK. Correlates of ever had sex among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents in Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:96. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0082-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winskell K, Miller KS, Allen KA, Obong'o CO. Guiding and supporting adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: The development of a curriculum for family and community members. Children and youth services review. 2016;61:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhury S, Brown FL, Kirk CM, et al. Exploring the potential of a family-based prevention intervention to reduce alcohol use and violence within HIV-affected families in Rwanda. AIDS care. 2016;28(sup2):118–129. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1176686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shamu S, Gevers A, Mahlangu BP, Shai PNJ, Chirwa ED, Jewkes RK. Prevalence and risk factors for intimate partner violence among Grade 8 learners in urban South Africa: baseline analysis from the Skhokho Supporting Success cluster randomised controlled trial. International health. 2015 doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv068. ihv068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. The lancet. 2006;368(9551):1973–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;337:a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. The Lancet Global Health. 2015;3(1):e23–e33. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. World Health Organization; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Christofides N, Jewkes R. Acceptability of universal screening for intimate partner violence in voluntary HIV testing and counseling services in South Africa and service implications. [2010/03/01];AIDS Care. 2010 22(3):279–285. doi: 10.1080/09540120903193617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sprague C, Hatcher AM, Woollett N, Black V. How Nurses in Johannesburg Address Intimate Partner Violence in Female Patients Understanding IPV Responses in Low-and Middle-Income Country Health Systems. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0886260515589929. 0886260515589929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stöckl H. A move beyond screening is required to ensure adequate healthcare response for women who experience intimate partner violence. Evidence Based Medicine. 2014;19(6):240–240. doi: 10.1136/ebmed-2014-110049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.García-Moreno C, Hegarty K, d'Oliveira AFL, Koziol-McLain J, Colombini M, Feder G. The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet. 2015;385(9977):1567–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, Swartz A, Lurie M. Sustained High {HIV} Incidence in Young Women in Southern Africa: Social, Behavioral, and Structural Factors and Emerging Intervention Approaches. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2015;12:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]