Abstract

Background

Improving care quality while reducing cost has always been a focus of nursing homes. Certified nursing assistants comprise the largest proportion of the workforce in nursing homes and have the potential to contribute to the quality of care provided. Quality improvement initiatives using certified nursing assistants as champions have the potential to improve job satisfaction, which has been associated with care quality.

Aims

To identify the role, use and preparation of champions in a nursing home setting as a way of informing future quality improvement strategies in nursing homes.

Methods

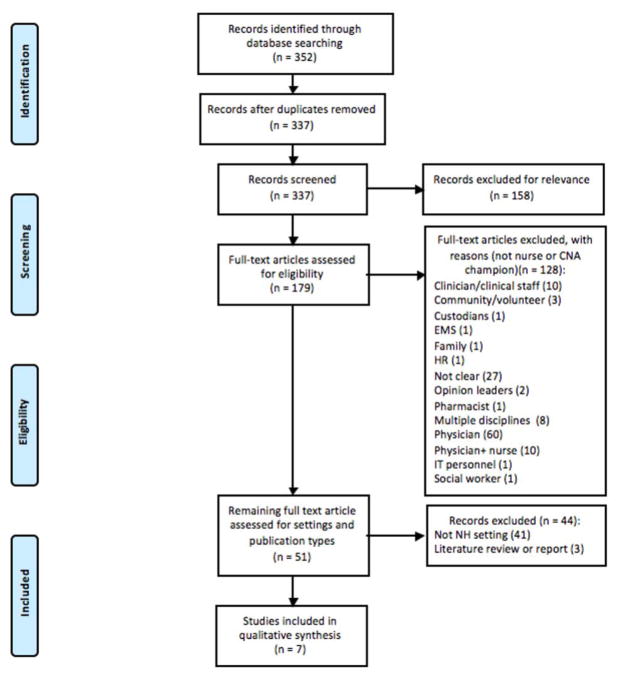

A systematic literature review. Medical Subject Headings and text words for “quality improvement” were combined with those for “champion*” to search Medline, CINAHL, Joanna Briggs Institute, MedLine In-Process and other Nonindexed Citations. After duplicates were removed a total of 337 potential articles were identified for further review. After full text review, seven articles from five original studies met inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis.

Results

Various types of quality improvement initiatives and implementation strategies were used together with champions. Champions were identified by study authors as one of the single most effective strategies employed in all studies. The majority of studies described the champion role as that of a leader, who fosters and reinforces changes for improvement. Although all the included studies suggested that implementing nurse or aid champions in their quality improvement initiatives were important facilitators of success, how the champions were selected and trained in their role is either missing or not described in any detail in the studies included in the review.

Linking Evidence to Action

Utilizing certified nursing assistants as quality improvement champions can increase participation in quality improvement projects and has the potential to improve job satisfaction and contribute to improve quality of care and improved patient outcomes in nursing homes.

Keywords: Champion, quality improvement, nursing homes, nurses, nurses’ aids

Introduction

There are approximately 15,700 nursing homes in the United States, providing care to 1,383,700 residents of whom 42% are 85 years or over and 28% aged 75–84 (Harris-Kojetin, Sengupta, Park-Lee, & Valverde, 2013). In 2015 expenditure on nursing care facilities and continuing care retirement communities reached $156.8 billion, an increase of 2.7% from 2014 (Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, 2015). With the increasing costs associated with providing long term care to an older population with significant co-morbidity, there has been an emphasis on both providing high quality of care to residents in the nursing home sector, whilst also reducing costs. The majority of the nursing home workforce in the US are Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs); 65% of nursing home staff compared to 12% Registered Nurses (RNs; Harris-Kojetin et al., 2013). CNAs are an unregulated workforce who have received a minimum of 75 hours of training, including at least 16 hours of supervised practice or clinical training (https://phinational.org/policy/nurse-aide-training-requirements-state). They provide the majority of personal care (such as bathing, feeding and dressing) to nursing home residents and it could be argued are an essential part of the workforce contributing to the quality of care given to residents (Estabrooks, Squires, Hayduk et al., 2015).

A number of quality improvement (QI) programs have been implemented in a nursing home setting, highlighting positive impacts on outcomes such as hospitalization rates (Ouslander et al., 2011), pressure ulcers and weight loss (Rantz et al., 2012). However, studies have also highlighted considerable diversity in the engagement of nursing homes with QI initiatives (Ouslander et al., 2011; Rantz et al., 2012) and there are concerns that some nursing homes do not have the mechanisms in place to implement quality assurance and performance improvement programs (Smith, Castle, & Hyer, 2013).

QI interventions often use a multifaceted approach to try and improve patient outcomes. This involves using a variety of components such as education and training, audit and feedback, using reminders to prompt practice and organizational restructuring, either individually or in combination to improve patient outcomes for one quality indicator or across a number of indicators (Low et al., 2015). However, there is no consistency in approaches used to evaluate such interventions and it is unclear what interventions are effective in improving outcomes. A systematic review of the research methods to study QI effectiveness identified relatively little research exploring the relationship between formal QI interventions or changes in practice and patient outcomes (Alexander & Hearld, 2009). This study reviewed QI interventions in healthcare organizations and found only 3.8% of studies (7 articles) were in a nursing home setting compared to 62% (114 articles) in hospitals (total number of studies in review = 185).

One component of a number of QI interventions is the use of “champions”; individuals who are instrumental in leading or promoting change from within an organization (Ploeg et al., 2010). The use of champions appears to be diverse and can be at different levels within an organization, such as executive champions (who have a senior leadership position), managerial champions (who have responsibility managing clinical departments, wards or units) and clinical champions (frontline clinicians; Soo, Berta, & Baker, 2009). The roles that champions fulfill are considered to be equally diverse and can include being advocates for a practice change (Fesmire, Peterson, Roe, & Wojcik, 2003), to facilitate the implementation of protocol interventions (Kaasalainen et al. 2015) or to encourage and engage staff in QI initiatives (Rantz et al., 2012). There is considerable support for having multiple champions within an organization who may co-operate or “co-perform” behaviors to accept the innovation or change in practice (Soo, Berta, & Baker, 2009; Van Laere & Aggestam 2016). Behaviors that champions have been identified as performing include education (among peers and other staff), acting as a resource or mentor (including the modelling and reinforcing of desired behaviors), advocacy and leadership, relationship building and the navigation of boundaries (Soo et al., 2009).

Given that CNA’s are a large part of the Nursing Home workforce and have a key role in the provision of direct care they may also have a key role in the implementation of QI initiatives. Norton, Cranley, Cummings, & Estabrooks (2013) have shown that it is feasible to develop QI teams in nursing homes led by health care assistants (the Canadian equivalent of the CNA) and that their introduction was associated with an improvement in outcomes in 50% of the QI teams. In addition, a recent study explored the concept of a “peer reminder” role for health care assistants, where individuals would offer brief formal reminders to their peers regarding a new innovation during regular meetings as well as informally when opportunities arise during a shift (Slaughter et al., 2017). Whilst this role is not seen to be the equivalent of a “champion” the qualities that a peer reminder should possess (as identified through focus groups with health care assistants) are similar to those qualities perceived to be possessed by champions from other research; someone who is already respected by the team, informally helping others and demonstrating leadership qualities (Shaw et al., 2012). The study also highlighted the importance of good communication skills and support from the rest of the team.

Existing evidence suggests that increased decision making autonomy and empowerment of CNAs is associated with higher job satisfaction and efficacy, and could lead to lower turnover (Chamberlain, Hoben, Squires, & Estabrooks, 2016). Including CNAs as part of a QI team or providing them with a “champion” role alongside other staff may provide such empowerment, thereby leading to improved outcomes for patients. The aim of this systematic review was to identify the role, use and preparation of champions in a nursing home setting as a way of informing future QI improvement strategies in nursing homes. It addressed the following questions:

In studies that have introduced a QI intervention in a nursing home setting that have used nurses and/or CNAs as champions as part of the implementation strategy: (a) Who were the champion(s)—in terms of their education or experience and role in the organization? (b) What education or training did the champion(s) receive to help them in their role? (c) What was the role of the champion—how did they support the implementation of change in the organization?

The purpose of the review was to identify if CNAs have been used as champions in existing QI studies in a nursing home setting, and if not how feasible it would be to include them as champions in QI projects in the future.

Methods

Search Strategy

The search was constructed using the following PICO question: (P) Nurses working in nursing homes; (I)Quality Improvement Intervention and Champion; (C) no comparison; (O) Data on improvement in patient outcomes. The search was conducted on the following electronic data bases: Ovid Medline, CINAHL, Joanna Briggs Institute, MedLine In-Process and other Non-indexed Citations from 1946 through to September 2016. The search included MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) for QI “Quality Assurance, Health Care or Total Quality Management or QI” and free text of “quality improvement” and free text search of the phrase “Champion*” (Table S1). The search was restricted to published studies, in English. The review focused on studies using QI initiatives in a health care setting, so the search was not extended to non-health care databases.

Study Eligibility

Studies were included in the review if they were conducted in a nursing home setting, reported the use of a QI initiative and implementation, were primary research (either qualitative or quantitative design) and that had used a nurse or CNA as a champion as part of the QI initiative. Studies were excluded if they were not conducted in a nursing home setting, used other health care professionals or non-professionals as champions, did not report primary results of a QI intervention (i.e., opinion or discussion pieces) and were not published in English.

Study Selection

After duplicates were removed the title and abstract for all references were independently reviewed by two reviewers for potential inclusion. At this point if there was any discrepancy in the agreement for inclusion for review the full text was retrieved. Both reviewers independently screened the full text of potentially eligible studies and identified publications that met the inclusion criteria or were excluded, with reasons for exclusions. Any disagreements on inclusion or exclusion were reached by consensus.

Data Extraction

Data for each study were extracted by one reviewer. This included the study design, the focus of the QI intervention, details of the QI implementation strategies used in the project, and information about the champions (their role, who they were, how they were identified, how they were trained) and the outcomes of the QI project (what effect did the intervention have on clinical outcomes).

Assessment of Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Potential bias in the included studies was evaluated using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS), which was developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project, Canada (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2007) and is used to assess both study quality and risk of bias of the results of quantitative studies. Reliability and validity of the QATQS have been demonstrated (Armijo-Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo, & Cummings, 2012; Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins, & Micucci, 2004). Two authors used the QATAS to independently evaluate each included study for areas of bias (potential selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and drop-outs). For each potential area of bias the rater gives a rating of strong (low risk of bias), moderate (moderate risk of bias) and weak (high risk of bias). On the basis of these ratings each study is then given a global rating of the overall risk of bias. After independently rating each article, any discrepancies in the evaluation of bias were agreed through consensus. Full details of the scoring for each included study is provided in the (Table S2).

Synthesis of Results

Following data extraction, a narrative synthesis of the data was conducted, which focused on the type of champion (who they were and how they were identified), if and how they were trained for their role and their role in the QI initiative. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity of the study designs, interventions used and the nature of the champion role.

Results

Study Selection

The initial search identified 337 potential studies (after duplicates were removed). Of these 158 were excluded following title and abstract review, with 179 articles retrieved for full text review (Figure 1). A further 128 were excluded as they did not focus on nurses or CNAs as champions.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Of the 51 articles that used either a nurse or CNA as a champion, three did not have study data and 41 were not conducted in a nursing home. This left seven articles, which were reporting data from five studies included in the final review (there were two studies which published results in two separate papers (Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Hicks et al. 2012; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012,). The two studies that had multiple papers reported both quantitative and qualitative research findings.

Study Characteristics and Risk of Bias

The characteristics for each of the five included studies are provided in Table S3. The focus of QI improvements were diverse including fall prevention (Bonner et al., 2007), management of heart failure patients (Dolansky, Hitch, Pina, & Boxer, 2013), pain management (Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015), pressure ulcer prevention (Sharkey et al., 2013) and a number of quality indicators (Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Hicks et al. 2012; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012). In all the studies champions were part of a multifaceted QI implementation strategy. Only one of the five studies (Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Hicks et al. 2012; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012) was rated as strong (with a low risk of bias). One study was identified as having a moderate risk of bias, with the main weakness being the risk of confounders in the study design (Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015). The remaining studies were all rated as weak, with a high degree of bias; mainly due to weaknesses in study design, the presence of potential confounders and problems with the reliability and validity of data collection methods (Bonner, MacCulloch, Gardner, & Chase, 2007; Dolansky et al., 2013; Sharkey et al., 2013).

Synthesis of Results

The definition of a champion

There was variation across the studies in the individuals who were designated as having a champion role. One study used CNAs as champions (Bonner et al., 2007). Other champions included both licensed nurses and nursing assistants (Dolansky et al., 2013) and advanced practice nurses (either a Clinical Nurse Specialist or a Nurse Practitioner; Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015). Exactly who the champions were in the remaining studies was unclear; in one it was “most commonly” a Director of Nursing (DON) or administrator (Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Hicks et al. 2012; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012), and in the other it was internal champions (without specifying their precise education or experience) with the team leads identified as either education directors or DON or Nursing Home Administrator (NHA) (Sharkey et al., 2013). Champions were selected for the role by the Nursing Home director in two studies (Bonner et al., 2007; Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015); with it being unclear how they were identified in the remaining three studies.

Education or training of the champion

There was little detail in the studies on the training that was provided to champions to enable them to fulfill their role. Bonner et al. (2007) stated that the CNA champions in their study were given peer leadership training, and the licensed nurses and nursing assistants in the study by Dolansky et al. (2013) were trained using a 1-day workshop (though there is no detail on what that training encompassed). In all five studies members of the research team or individuals employed either as research nurses or coaches by the team were actively involved in assisting the facilities with QI implementation.

The role of the champion

Although the types of champions were varied, the role of the champion was similar. The majority of studies described the champion role as that of a leader, who fosters and reinforces changes for improvement. Champions in these studies were expected to “enhance surveillance”, “guide or reinforce implementation”; “create coalition or assemble groups” (Bonner et al., 2007; Dolansky et al., 2013; Sharkey et al., 2013). In a more in-depth evaluation of the champions’ role Kaasalainen et al. 2015 suggest that champions used a variety of strategies to promote QI including educational outreach, reinforcing the use of protocols through reminders, chart audits and working group meetings.

All the included studies suggested that the champions were important facilitators of the success and achievement in their QI initiatives. Champions were identified as one of the important facilitators of HF management protocols implementation among others (Dolansky et al., 2013) and key to successful pain management (Kaasalainen et al., 2012). The presence of an internal champion was one of the characteristics of facility teams that were associated with a high level of QI implementation (Sharkey et al., 2013) and having a “change champion” was identified as making it more likely that a nursing home would continue QI initiatives (Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Hicks et al. 2012; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012)

Strong leadership engagement both from administrative and clinical leaders was also identified in all of the studies as a facilitator of QI projects (Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012; Sharkey et al., 2013). Leadership engagement was seen to be important to enable champions to perform their roles as facilitators in implementation of evidence based practices. Administrative support has also been identified as important from other literature that looked at key success factors for QI in a hospital setting (Parkosewich, Funk, & Bradley, 2005). Barriers to the effective use of champions in QI improvement projects included high turnover of leadership, such as DONs or NHAs, as well as nursing home staff (Kaasalainen et al., 2015; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012; Sharkey et al., 2013;). High leadership turnover will weaken continued support to champions in performing their role as expected, Diverse current quality problems in a facility and heavy workload were also identified as barriers to achieving desired quality outcomes due to distractions on focus areas (Kaasalainen et al., 2015; Sharkey et al., 2013).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to identify the nature of champions involved in QI interventions in a nursing home setting. Whilst there is a considerable literature on QI in a hospital setting, there is relatively little substantial research conducted in nursing homes (Alexander & Hearld, 2009). We identified five studies that have used champions as part of their QI initiatives in a nursing home setting, with mixed outcomes, that appear to be more dependent on the level of engagement of the nursing homes in the QI process, than any particular strategy or intervention used as the basis for the QI initiative. However, it was notable that all the studies identified the use of champions as a key factor in successful implementation.

Our review identified a lack of consistency across studies in terms of who champions may be and a lack of information on how they are initially identified. The broader literature on champions highlights that they may be at different levels within an organization, and may therefore have different initial skills and experience to support them in the role (Ploeg et al., 2010; Soo et al., 2009). While three of the studies reported the use of either senior management or advanced nurses in the champion role (Hicks et al. 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2012; Kaasalainen et al., 2015; Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Rantz, Zwygart-Stauffacher, Flesner et al. 2012; Sharkey et al., 2013), two studies appeared to use less educated staff, particularly nursing assistants and CNAs in this role (Bonner et al., 2007; Dolansky et al., 2013). Whilst CNAs or nursing assistants may not have the equivalent levels of education and training of that received by registered nurses, advanced nurses and DONs, they do provide the majority of clinical care to residents in nursing homes (Estabrooks, Squires, Carleton et al., 2015; Estabrooks, Squires, Hayduk et al., 2015), and are therefore directly responsible for the implementation or not of a number of evidence based practices. Previous studies have also indicated that it is possible to implement QI interventions with CNAs or nursing assistants as the team leaders (Norton et al., 2013), and that they may have a formal role as “peer reminders” within a nursing home setting (Slaughter et al., 2017). Further insights into how individuals who perform the champion role are identified and selected would be beneficial, as at present this appears to be more focused on specific characteristics of the individual (e.g., their perceived existing informal leadership skills or commitment to the organization), or their administrative role within an organization (e.g., as Director of Nursing) than any formal consideration of the mixture of skills, education and experience that might be required (either individually or co-shared across a team) to fulfill the champion role.

It was also unclear from the studies identified in the review what specific education or training a champion may need in order to fulfill their role. Two of the five studies mentioned specific training for the champions, and only one indicated briefly what it consisted of (peer leadership; Bonner et al., 2007). The role of the champion appears complex, with studies reporting that the champions have varied responsibilities including education (both formal and informal), role modelling of behaviors, developing materials (such as posters) to remind staff of best practices, conducting audit and feedback activities, and more general advocacy and communication across the organization to create a culture of change (Kaasalainen et al., 2015; Soo et al., 2009). Whilst more educated and experienced staff may have developed these skills through their educational programs, it is likely that unregulated staff (such as CNAs or nursing assistants) may need more training and support to fulfill this role, or may need to be part of a broader team where these skills are shared across individuals.

The review suggests that although champions could be seen as an important part of multifaceted approaches to QI in nursing homes, more evidence is needed on the details of their role, selection, and training processes. Using CNAs as champions has the potential to both support and facilitate QI and enhance patient outcomes, and may also have other effects such as a reduction in turnover and an improvement in staff morale; all of which need to be further explored and tested. Without more detail on how to prepare champions for their role, and more explicit detail on what they do to facilitate QI it is unclear how CNAs could be used effectively to promote QI.

Limitations

The review only assessed published research and was limited to the English language. However, given the nature of most QI initiatives, the search strategy was likely to identify those studies that had used rigorous methods across sites to evaluate QI interventions. An additional limitation is the focus on nurses or CNAs specifically as champions, which excluded a large numbers of studies that used other professions (particularly physicians) in this role. However, given the nature of the care setting, where nurses and CNAs are the key staff engaged in daily care of residents, the likelihood of excluding relevant studies was diminished.

Conclusions

The five studies included in this review identified variability in the use of champions as part of QI interventions in a nursing home setting. Only one of the five identified studies used CNAs exclusively to perform the role of champion. Given the large numbers of CNAs in the nursing home workforce, and their central role in the delivery of patient care, there is potential for the further development of CNAs to be involved in QI improvement initiatives. However, there also needs to be more rigorous research to explore how to identify QI champions, how to prepare them for their role, further exploration of what their role entails, and how this then may translate to positive outcomes for patients.

Supplementary Material

Linking Evidence to Action.

CNA’s can be used successfully as QI champions in a nursing home setting

The inclusion of CNA’s as QI champions has the potential to improve quality of care and job satisfaction

Champions are important facilitators of successful QI initiatives in a nursing home setting

Strong leadership is required to help facilitate the champion role

There is currently a lack of consistency in the identification and training of QI champions in a nursing home setting

Contributor Information

Kyungmi Woo, Doctoral Candidate, Columbia University School of Nursing, New York, NY, USA.

Gvira Milworm, Chief Process Officer, Elderly Health Promotion Inc. and DBA Institute for Pressure Injury Prevention, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Dawn Dowding, Professor of Nursing, Columbia University School of Nursing, and Center for Home Care Policy and Research, Visiting Nurse Service of New York, New York, NY, USA.

References

- Alexander JA, Hearld LR. What can we learn from quality improvement research? A critical review of research methods. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(3):235–271. doi: 10.1177/1077558708330424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2012;18(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner A, MacCulloch P, Gardner T, Chase CW. A student-led demonstration project on fall prevention in a long-term care facility. Geriatric Nursing. 2007;28(5):312–318. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SA, Hoben M, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Individual and organizational predictors of health care aide job satisfaction in long term care. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16(1):577. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1815-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. Highlights. 2015. National health expenditure data. [Google Scholar]

- Dolansky MA, Hitch JA, Pina IL, Boxer RS. Improving heart failure disease management in skilled nursing facilities: Lessons learned. Clinical Nursing Research. 2013;22(4):432–447. doi: 10.1177/1054773813485088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Carleton HL, Cummings GG, Norton PG. Who is looking after Mom and Dad? Unregulated workers in Canadian long-term care homes. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2015;34(1):47–59. doi: 10.1017/S0714980814000506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hayduk L, Morgan D, Cummings GG, Ginsburg L, … Norton PG. The influence of organizational context on best practice use by care aides in residential long-term care settings. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015;16537(6):e531–e510. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesmire FM, Peterson ES, Roe MT, Wojcik JF. Early use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in the ED treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a local quality improvement initiative. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2003;21(4):302–308. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R. Long-term care services in the United States: 2013 overview. Vital Health Statistics. 2013;3(37):1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S, Brazil K, Akhtar-Danesh N, Coker E, Ploeg J, Donald F, … Papaioannou A. The evaluation of an interdisciplinary pain protocol in long term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(7):664, e661–e668. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S, Ploeg J, Donald F, Coker E, Brazil K, Martin-Misener R, … Hadjistavropoulos T. Positioning clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners as change champions to implement a pain protocol in long-term care. Pain Management Nursing. 2015;16(2):78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low LF, Fletcher J, Goodenough B, Jeon YH, Etherton-Beer C, MacAndrew M, Beattie E. A systematic review of interventions to change staff care practices in order to improve resident outcomes in nursing homes. PloS one. 2015;10(11):e0140711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton P, Cranley L, Cummings G, Estabrooks C. Report of a pilot study of quality improvement in nursing homes led by healthcare aides. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare. 2013;1(1):255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, Herndon L, Diaz S, Roos BA, … Bonner A. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(4):745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkosewich J, Funk M, Bradley EH. Applying five key success factors to optimize the quality of care for patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;20(3):111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2005.04319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, Skelly J, Rowan M, Edwards N, Davies B, Grinspun D, … Downey A. The role of nursing best practice champions in diffusing practice guidelines: A mixed methods study. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2010;7(4):238–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Hicks L, Mehr D, Flesner M, Petroski GF, … Scott-Cawiezell J. Randomized multilevel intervention to improve outcomes of residents in nursing homes in need of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Flesner M, Hicks L, Mehr D, Russell T, Minner D. Challenges of using quality improvement methods in nursing homes that “need improvement”. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(8):732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey S, Hudak S, Horn SD, Barrett R, Spector W, Limcangco R. Exploratory study of nursing home factors associated with successful implementation of clinical decision support tools for pressure ulcer prevention. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2013;26(2):83–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000426718.59326.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw EK, Howard J, West DR, Crabtree BF, Nease DE, Tutt B, Nutting PA. The role of the champion in primary care change efforts: from the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices and Partners (SNOCAP) The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2012;25(5):676–685. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.110281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter SE, Bampton E, Erin DF, Ickert C, Jones CA, Estabrooks CA. A novel implementation strategy in residential care settings to promote EBP: Direct care provider perceptions and development of a conceptual framework. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2017;14(3):237–245. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM, Castle NG, Hyer K. Implementation of quality assurance and performance improvement programs in nursing homes: A brief report. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14(1):60–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soo S, Berta W, Baker GR. Role of champions in the implementation of patient safety practice change. Healthcare Quarterly. 2009;12(Special Issue):123–128. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2009.20979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere J, Aggestam L. Understanding champion behaviour in a health-care information system development project–how multiple champions and champion behaviours build a coherent whole. European Journal of Information Systems. 2016;25(1):47–63. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.