Abstract

Background

PrEP is efficacious for African women at risk for HIV, but data on adherence outside of clinical trials are sparse. We describe the persistence and execution of PrEP use among women participating in a large open-label PrEP demonstration project, particularly during periods of HIV risk.

Setting & Methods

310 HIV-uninfected women in HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda were offered and accepted PrEP. Electronic monitoring caps were used to measure daily PrEP adherence. Time on PrEP while at risk for HIV (when the HIV-infected partner was on ART <6 months) and weekly adherence while on PrEP were calculated and compared among older and younger (<25 years old) women.

Results

As defined above, women were at risk for HIV for an average of 361 days; 54% took PrEP during their entire risk period and 24% stopped but re-started PrEP during their risk period. While on PrEP, women took ≥6 doses/week for 78% of weeks (67% of weeks for women <25 years old, 80% of weeks for women ≥25 years [p<0.001]), and ≥4 doses for 88% of weeks (80% for those <25, 90% for those ≥25, [p<0.001]). Compared to historical, risk-matched controls, HIV incidence was reduced 93% (95% CI 77%–98%) for all women and 91% (95% CI 29% –99%) among women <25 years old.

Conclusion

Women, including young women, in HIV-serodiscordant couples took PrEP successfully over sustained periods of risk. While young women had lower adherence than older women, they achieved strong protection, suggesting women can align PrEP use to periods of risk and imperfect adherence can still provide substantial benefit.

Keywords: women, HIV, adherence, PrEP

Introduction

Young African women are at particularly high-risk for HIV; 25% of new infections in Sub-Saharan Africa occur in women aged 15–24, compared to 12% in the men of the same age.1 Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an effective method of HIV prevention, including for women, when adherence is high.2 However, concerns have been raised about the ability of women and particularly young women to take PrEP at sufficient levels to provide protection. The level of adherence necessary to achieve protection in women has been debated, with pharmacokinetic modeling analyses suggesting higher dosing is needed to achieve protective levels in cervical tissue (i.e., ≥6 doses per week), compared to ≥4 doses per week in rectal tissue.3 Adherence to PrEP among women in clinical trials varied widely 4,5, and adherence may be higher outside of clinical trials, when PrEP is offered as a known effective prevention tool rather than an experimental drug.6,7 We used data from a large implementation study that demonstrated a strong protective effect against HIV infection to describe the persistence and execution of PrEP use among East African women in HIV serodiscordant couples during periods of HIV acquisition risk, focusing on women <25 years of age.

Methods

Study Population

Enrollment in the Partners Demonstration Project and the counseling provided to participants has been previously described.8–10 HIV serodiscordant couples who mutually disclosed their HIV status were selected, using an empiric risk score (≥5) which was associated with HIV infection rates of >3% per year in the uninfected parter.11 Using a strategy of “PrEP as a bridge to ART,” HIV uninfected partners were encouraged to take PrEP until their partners had initiated ART (not all HIV infected partners were eligible or chose to start ART at enrollment) and were on ART for six months, at which time their viral load would likely be suppressed. A total of 1,013 couples, 334 with female HIV-uninfected partners, were enrolled at two sites each in Kenya and Uganda. Women who were found to have been HIV positive at baseline (n=6), who lacked electronic monitoring data (n=7), or who did not initiate PrEP (n=11) were excluded, leaving 310 HIV uninfected women in the analysis. All participants provided written informed consent in their preferred language.

Participants were given electronic monitoring devices (MEMS caps, WestRock, Switzerland), which recorded daily bottle openings. MEMS data were downloaded and other variables collected at quarterly study visits, at which time three months of PrEP (emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 200mg/300 mg) was dispensed. While initially women were not given PrEP during pregnancy, the protocol was revised midway to permit women to take PrEP during pregnancy if they chose. Study-related drug stops were implemented if a participant: acquired HIV; reported a severe, study-related adverse event; began breastfeeding; had creatinine clearance <60mL/min; or at the study physician’s discretion.

Statistical analysis

Analyses focused on persistence and execution of PrEP adherence. Persistence was calculated as the time period on PrEP divided by the time period at risk, reported as a percent. By this definition, persistence can be >100% if time on PrEP exceeds the estimated time at risk.12 Time on PrEP was determined as the time from PrEP initiation until the earliest of: HIV seroconversion, 28 consecutive days of recorded non-use by MEMS cap, or study end. HIV risk is highest when the infected partner is not virally suppressed; however, sexual activity is also a factor. Therefore, risk was defined in two ways: any time until the HIV-infected partner had achieved ≥6 months on ART (at risk) and any time prior to ≥6 months on ART until the woman first reported no sexual activity over the previous month (at high risk). Execution was defined as the number of weekly doses while the participant had PrEP dispensed. For all analyses, participants were censored at seroconversion or study-related drug stops.

Descriptive statistics for persistence and execution were calculated overall and separately for younger women (under <25 years of age at enrollment) and older women; comparisons between these age groups were conducted, using Chi-square tests for categorical outcomes and T-tests for continuous outcomes. A counterfactual analysis was used to estimate the protective effect of PrEP against HIV acquisition, as there was no placebo group; this analysis used bootstrap resampling simulations of placebo-arm participants in an HIV-prevention clinical trial, matched on gender, risk score, time in study, and, as needed, age (< or ≥25 years old) to calculate the expected and observed HIV incidence rates, as previously described.8 All analyses were done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

Of the 310 women included in the analysis, 24% were <25 years at baseline. Among all the women, 97% were married to their study partner, for an average of 7.4 years, and had on average 1.6 children with their partner; couples knew their serodiscordant status for 0.7 years on average. Young women were more likely to report ≥8 years of education and shorter relationships with their study partner.

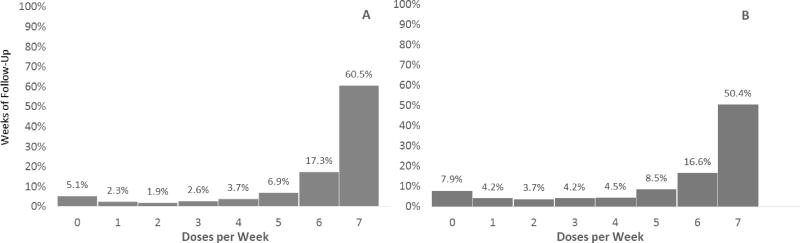

There were 10,871 weeks of follow-up time on PrEP. Overall, women recorded ≥6 weekly doses for 78% of weeks on PrEP (regardless of risk) (Figure 1). Doses recorded per week differed significantly by age, as young women took ≥6 doses for 67% of weeks and older women for 80% of weeks, p<0.001. Using a lower cut-off, 88% of weeks had ≥4 recorded doses, with younger women recording ≥4 doses for 80% of weeks, compared to 90% of weeks among older women, p<0.001.

Figure 1.

Weekly Doses While on PrEP Among All Women (A) and Women <25 (B)

Overall, women were at risk (i.e., HIV infected partner not yet on ART for ≥6 months) for an average of 361 days (Table 1) and time at risk did not differ between younger and older women (367 days and 360 days respectively, p=0.73). The median persistence was 100% (IQR 38%, 100%) and 54% of women recorded PrEP use for the entire risk period or longer, (i.e. ≥100% persistence). There was a significant difference by age, with 41% of younger women compared to 58% of older women recording PrEP use for their entire risk period or longer, p=0.01.

Table 1.

Persistence & Time at Risk, by Age

| At Risk | At High Risk | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Women (n=310) |

Women <25 (n=73) |

Women ≥25 (n=237) |

p- value* |

All Women (n=309) |

Women <25 (n=73) |

Women ≥25 (n=236) |

p- value* |

|

| Persistence >100% | 54% | 41% | 58% | 0.01 | 63% | 49% | 67% | 0.006 |

| Mean Days at Risk (SD) | 361 (170) | 367 (173) | 360 (169) | 0.73 | 282 (171) | 284 (160) | 281 (175) | 0.88 |

Chi square or T-test (unequal variance)

Of the 142 (46%) women who stopped PrEP while still at risk, 51% reinitiated PrEP (i.e., at least one MEMS cap opening) during their risk period; this includes 47% of younger women and 53% of older women, p=0.51. Additionally, among the 51 women whose partners initiated ART at baseline, 76% recorded PrEP use for their entire risk period, including 62% of younger women and 82% of older women, p=0.25. However, among the 259 women whose HIV-infected partners did not initiate ART at baseline (including those whose partners never initiated ART), 50% recorded PrEP use for their entire risk period, including 37% of younger women and 54% of older women, p=0.02.

The average duration of the high-risk period (i.e., partner <6 months ART until the first report of no sexual activity) was 282 days (Table 1), and the duration was similar for younger and older women (284 and 281 days respectively, p=0.88). Among all women, 63% recorded PrEP use for their entire high-risk period (or longer), with 49% of young women recording PrEP use for the entire high risk period, compared to 67% of older women, p=0.006.

A total of three seroconversions were observed among women in the study, for an incidence rate of 0.5 per 100 person-years. The counterfactual analysis predicted an incidence rate of 7.6 per 100 person-years among all women (42.1 cases expected), for a protective effect of 93% (95% CI 77%, 98%). Similarly, among women under 25, one serconversion was observed, for a rate of 0.7 per 100 person-years, while the expected rate was 7.8 per 100 person-years with 11.4 cases expected, for a protective effect of 91% (95% CI 29%, 99%). The woman <25 years who acquired HIV infection was on PrEP for 27% of her risk period and while on PrEP, 4 out of 15 weeks recorded ≥4 doses; the six weeks prior to seroconversion recorded ≤2 doses per week. Of the two older women who seroconverted, one lacked MEMS data. The other was on PrEP until her seroconversion, with ≥4 doses reported 5 out of 12 weeks; the last four weeks had ≤2 doses.

Discussion

Women in this demonstration project were at sustained risk for HIV and the majority effectively used PrEP while at risk. More than half of women (54%) recorded PrEP use for their entire risk period or longer, 23.5% stopped and reinitiated PrEP while at risk, and only 22.5% stopped completely while at risk. While on PrEP, women recorded ≥6 doses for 78% of weeks and ≥4 doses for 88% of weeks. This degree and pattern of adherence resulted in an estimated 93% protection against HIV.

Pharmacokinetic data have been interpreted to suggest 6–7 weekly doses may be required to achieve protection from HIV in the female genital tract.3 We found that the majority (78%) of, but not all, time on PrEP recorded ≥6 weekly doses – and, importantly, with that pattern of use HIV protection was high. Prior studies indicate that HIV uninfected individuals align their PrEP use with periods of risk12–14, which may explain the strong protective effect even with imperfect adherence. Messaging about using PrEP during ‘seasons’ of risk may help women understand that PrEP use is short term, unlike lifelong ART use, and may increase PrEP uptake and adherence.6,15 However, daily dosing should be emphasized during these seasons of risk to optimize efficacy and establish consistent adherence routines.16

Prior studies have demonstrated that unique HIV risks and adherence challenges exist for young adults.13 In the iPrEx study of MSM and transgender women, younger men (18–24 years old) were less likely to have PrEP detected in blood samples.17 In addition, results from a study of dapivirine ring use found no protective effect among women under 21.18 In the present study, time at risk was similar between younger and older women. However, younger women were less likely to use PrEP during their time at risk and while on PrEP they were less likely to have ≥6 doses per week, supporting the idea that they may face greater challenges to adherence.19 Nevertheless, many women <25 years of age in this study took PrEP, with sustained persistence and high execution, and the HIV protection achieved in the population was high. Better understanding of how young women perceive their HIV risk and whether adherence increases during periods of perceived risk will be useful in reducing adherence barriers for this population. In addition, there may be other barriers, such as family and partner influences, that disproportionately affect young women.20–22

There are several limitations to this study. While MEMS caps provide day-level data, they are a proxy for actual doses and can be over or under-reported.23 However, previous work has shown that electronic monitoring can detect regular PrEP users, as supported by plasma tenofovir levels.24 Data on seroconversion, sexual activity, and ART initiation were collected quarterly and data on outside partners was insufficient to assess HIV risk, leading to imprecision in calculating risk periods and potential misclassification. Only mutually-disclosed HIV-serodiscordant couples were included, and the results may not be generalizable to all women. In particular, defining risk may be more clear-cut in a serodiscordant couple (i.e., before the HIV-infected partner is virally suppressed) and PrEP may be seen as a way for couples to maintain the relationship.25,26

The strengths of this analysis include large sample size, longitudinal data, use of electronic monitoring, and the inclusion of risk in assessing adherence. Our results do not provide a threshold of PrEP use for HIV protection in women, but they demonstrate that patterns of PrEP use outside of clinical trials are associated with very low HIV risk, even in a population that would otherwise be at very high risk for acquiring HIV.

In conclusion, PrEP is an effective HIV-prevention tool for East African women in serodiscordant couples. Women, including women <25 years of age, are able to adhere to PrEP over sustained periods of risk at levels that provided significant protection. While women should aim for daily PrEP use during seasons of risk, the threshold of perfect adherence should not be expected or become a barrier to PrEP delivery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the couples who participated in this study.

Funding

The Partners Demonstration Project was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (R01 MH095507), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1056051), and the US Agency for International Development (AID-OAA-A-12-00023). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, NIH, or the United States Government.

Partners Demonstration Project Team

Coordinating Center (University of Washington) and collaborating investigators (Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital): Jared Baeten (protocol chair), Connie Celum (protocol co-chair), Renee Heffron (project director), Deborah Donnell (statistician), Ruanne Barnabas, Jessica Haberer, Harald Haugen, Craig Hendrix, Lara Kidoguchi, Mark Marzinke, Susan Morrison, Jennifer Morton, Norma Ware, Monique Wyatt

Project sites:

Kabwohe, Uganda (Kabwohe Clinical Research Centre): Stephen Asiimwe, Edna Tindimwebwa

Kampala, Uganda (Makerere University): Elly Katabira, Nulu Bulya

Kisumu, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute): Elizabeth Bukusi, Josephine Odoyo

Thika, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Washington): Nelly Rwamba Mugo, Kenneth Ngure

Data Management was provided by DF/Net Research, Inc. (Seattle, WA). PrEP medication was donated by Gilead Sciences.

Footnotes

Data was presented at HIV Research for Prevention (HIV R4P) 2016, October 17–21, in Chicago, IL , USA.

References

- 1.Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; [Accessed November 9, 2016]. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karim SSA. [Accessed May 4, 2016];The potential and challenges of ARV-based HIV prevention: An overview. 2014 Jul; http://slideplayer.com/slide/5909872/

- 3.Cottrell ML, Yang KH, Prince HMA, et al. A Translational Pharmacology Approach to Predicting HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Outcomes in Men and Women Using Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate±Emtricitabine. J Infect Dis. 2016 Feb; doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-Based Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution: from clinical trials to routine practice. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):10–17. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekker LG, Hughes JP, Amico R, et al. [Accessed November 9, 2016];HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape Town: A Comparison of Daily and Nondaily PrEP Dosing in African Women. 2015 Feb; http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/hptn-067adapt-cape-town-comparison-daily-and-nondaily-prep-dosing-african-women.

- 8.Baeten JM, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, et al. Integrated Delivery of Antiretroviral Treatment and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis to HIV-1-Serodiscordant Couples: A Prospective Implementation Study in Kenya and Uganda. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haberer JE, Kidoguchi L, Heffron R, et al. Alignment of adherence and risk for HIV acquisition in a demonstration project of pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda: a prospective analysis of prevention-effective adherence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morton JF, Celum C, Njoroge J, et al. Counseling Framework for HIV-Serodiscordant Couples on the Integrated Use of Antiretroviral Therapy and Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2017;74(Suppl 1):S15–S22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, Lingappa JR, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1 serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR, Baeten JM, et al. Defining success with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: a prevention-effective adherence paradigm. AIDS. 2015;29(11):1277–1285. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amico KR, Stirratt MJ. Adherence to Preexposure Prophylaxis: Current, Emerging, and Anticipated Bases of Evidence. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59(Suppl 1):S55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker L-G, et al. Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT Study-Provided Open-Label PrEP Among Women in Cape Town: Facilitators and Barriers Within a Mutuality Framework. AIDS Behav. 2016 Jun; doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1458-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mugo NR, Ngure K, Kiragu M, Irungu E, Kilonzo N. The preexposure prophylaxis revolution; from clinical trials to programmatic implementation. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):80–86. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chianese C, Amico KR, Mayer K, et al. Integrated Next Step Counseling for Sexual Health Promotion and Medication Adherence for Individuals Using Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(S1):A159–A159. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.5329.abstract. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, et al. Use of a Vaginal Ring Containing Dapivirine for HIV-1 Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506110. 0(0):null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celum CL, Delany-Moretlwe S, McConnell M, et al. Rethinking HIV prevention to prepare for oral PrEP implementation for young African women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18(4Suppl 3) doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.4.20227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, et al. Participants’ explanations for non-adherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery ET, der van Straten A, Stadler J, et al. Male Partner Influence on Women’s HIV Prevention Trial Participation and Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis: the Importance of “Understanding”. AIDS Behav. 2014;19(5):784–793. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0950-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s Experiences with Oral and Vaginal Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: The VOICE-C Qualitative Study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park LG, Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. Electronic measurement of medication adherence. West J Nurs Res. 2015;37(1):28–49. doi: 10.1177/0193945914524492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musinguzi N, Muganzi CD, Boum Y, et al. Comparison of subjective and objective adherence measures for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection among serodiscordant couples in East Africa. AIDS Lond Engl. 2016 Jan; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What’s Love Got to Do With It? Explaining Adherence to Oral Antiretroviral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Serodiscordant Couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2012;59(5) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel R, Stanford-Moore G, Odoyo J, et al. “Since both of us are using antiretrovirals, we have been supportive to each other”: facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis use in heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples in Kisumu, Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1) doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]