Abstract

Purpose

To examine barriers recruiters encounter when enrolling African American study participants, identify motivating factors to increase research participation, and provide recommendations to facilitate successful minority recruitment.

Background

Recruiters are often the first point of contact between the research study and potential African American participants. While challenges in enrolling African Americans into clinical and epidemiologic research has been reported in numerous studies the non-physician recruiter’s role as a determinant of overall participation rates has received minimal attention.

Methods

We conducted four 90-minute teleconference focus groups with 18 recruiters experienced in enrolling African Americans for clinical and epidemiologic studies at five academic/medical institutions. Participants represented diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and were asked to reflect on barriers preventing African Americans from participating in research studies, factors that motivated participation, and recommendations to increase participation of African Americans in research. Multi-coder and thematic data analysis was implemented using the Braun and Clarke method.

Results

Prominent concerns in recruitment of African Americans in research include fear and mistrust and inflexible research protocols. The participants suggest that improved recruitment could be achieved through cross-cultural and skillset building training opportunities for recruiters, greater community engagement among researchers, and better engagement with clinic staff and research teams.

Keywords: Minorities, Participation Rates, Recruiters, Observational Epidemiologic Studies, Barriers, Motivating Factors, Clinic Education

Introduction

Low participation in clinical research is an ongoing national problem where <3% of patients participate in clinical trials, and even fewer minorities are engaged (~2.5%).1,2 Lower participation rates among minorities, especially African Americans, have been documented in both observational epidemiologic studies and treatment trials.3,4

Under-representation of minorities in clinical and epidemiologic research has significant scientific implications. Lower participation rates among minority populations may compromise generalizability of research findings, raise concerns around biased reporting of adverse effects, and limit minorities from fully benefitting from research including access to cutting-edge therapies, thus contributing to racial health disparities.

The challenges of recruiting African Americans for clinical and epidemiologic research have been addressed in numerous research studies, focusing on diverse stakeholders and viewpoints.5,6 For example, several studies have emphasized the important role that physicians play in encouraging patient participation in research. In a lung cancer study designed to understand clinical research participation, they found most patients involved in research were invited by a provider or clinic team member. Interestingly, in the same study, patients who were not involved in research were not aware of or not asked about participating in research.5, 7-9 This highlights the critical role of physician/patient communication in clinical research recruitment. Conversely, lack of training in minority recruitment for referring physicians and limited communication between physicians and study teams have been identified as barriers to minority enrollment.5,6 Other studies illustrate the role of community health workers as trusted members in the community who have key skillsets to engage minorities, particularly hard-to-reach populations, in clinical research.10 These perspectives add value to the discourse on minority inclusion in research and provide some insight into the complex factors that influence participation.

These studies underscore that successful involvement of minorities in clinical research is determined by multiple individuals involved in the research enterprise. However, the role of one of the key players in clinical research – the non-physician recruiter/interviewer – has not been well-studied and little is known about their perspectives and recommendations related to recruitment and retention of minority participants, particularly African Americans, in clinical research.5,6,11,12

Non-physician recruiter/interviewers have firsthand experience with many of the documented barriers to participation in research including: mistrust based on historical and current medical abuses; lack of understanding of the purpose and process of research; the influence of social and familial relationships (gatekeepers); and competing priorities such as family or work responsibilities.8,13,14 The “guinea pig” syndrome is often cited as a key concern for minorities, even for observational studies where participants are not asked to take medications or undergo procedures. System barriers also limit minority participation, including a lack of discussing research as an opportunity for patients. Other system factors that influence participation include arduous consenting processes and non-flexible research protocols that do not accommodate real-life experiences and priorities of research participants.7,8

Some studies have examined interviewers’ impact on participation rates by looking at interviewer characteristics such as race, age and years of experience,1,15,16 but have not explicitly solicited the input and opinions of the recruiters. Interviewers/recruiters are often the first point of contact between the research study and the potential participant, and their interactions may be a prime determinant of overall participation rates. The role of the non-physician recruiter requires an intricate balance between the medical and research enterprise and the potential participants they strive to engage. This balance becomes even more salient as they recruit minority populations in research.

Skilled recruiters may be aware of common barriers to participation and may have developed approaches to identify and address these barriers and build rapport with some African Americans who might be apprehensive about participating in research. Generally, the scientific literature documenting barriers to participation, successful strategies implemented, and recommendations for resources and education to improve response rates focus on the referring physician’s perspective and not the recruiter’s expertise. To address this gap in knowledge, we conducted a series of focus groups with recruiters experienced in enrolling African Americans in observational epidemiologic studies, including case-control and prospective cohort studies. Our goal was three-fold: 1) to systematically gather exploratory information on the barriers non-physician recruiters encounter when enrolling African American study participants; 2) to describe approaches that increase the likelihood of research participation; and 3), formulate strategic recommendations to facilitate increased recruitment and retention rates.

Methods

We conducted four 90-minute focus groups via teleconference. Eighteen recruiters participated in the study, with an average of 4-5 participants per teleconference to enhance full participation. All recruiters were involved in multiple clinical/epidemiologic research studies that targeted recruitment of minorities, specifically African Americans. The participants included 2 males and 16 females, and represented diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds including African American, White, and Hispanic/Latino. Participants were from academic/medical institutions in the Midwest and eastern United States.

We disseminated invitations via e-mail and phone calls to offices and departments focused on epidemiology and clinical research to identify recruiters. Once initial contact was made, additional recruiters were identified through snowball sampling. Potential focus group participants received informed consent forms through the mail, were asked to review the document with the study coordinator and then returned the signed form. Once consented, focus group call-in information was provided. A $10 incentive was offered to each participant. The study protocol was approved by Duke University’s Institutional Review Board.

An experienced moderator and note-taker conducted each focus group. Sessions were digitally recorded, and lasted ~90 minutes. The call began with introductions, study overview, and protocols to be followed during the telephone-based focus group. The focus groups were structured around the following guiding questions: 1) What barriers do you face when recruiting African Americans into research studies? 2) What ways do psychosocial, cultural and economic factors play into the recruiting process? 3) What strategies have you used to overcome some challenges encountered when recruiting African Americans? 4) What resources, tools, and skills would you recommend to help you and your peers more effectively recruit African Americans in research?

Data Analysis

Focus group discussions were digitally recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo 11 Pro qualitative software. Three coders independently analyzed the data and identified initial codes and themes, which were refined by repeated application of codes to transcripts, cross checking and team discussion. Coders examined and compared emergent themes across each focus group. Codes were then refined and finalized. Themes were highly aligned across coders. A thematic analysis using a systematic, multistep, rigorous process outlined by Braun and Clarke7 was conducted to ascertain, compare and contrast themes and key concepts within and across the transcripts. Grounded theory shaped the design and analysis of the research.17,18

Results

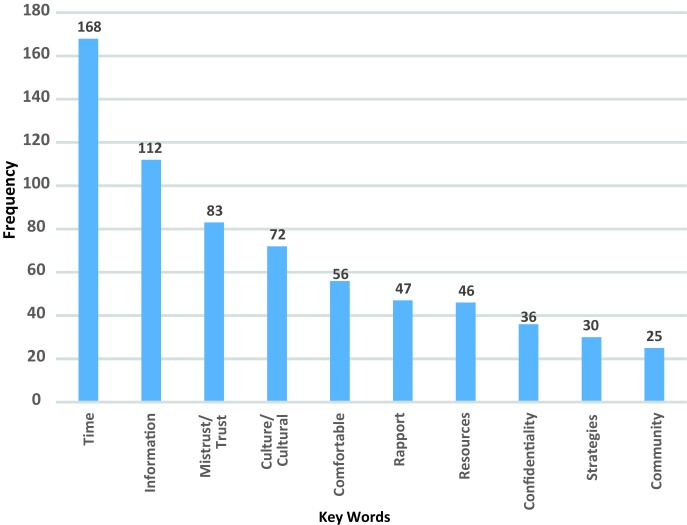

Focus group findings are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Described below are integral emergent themes organized by broad categories of identified barriers to participation and the strategies recruiters employ to overcome barriers. We also report recommended resources, skills, and support needed to successfully enroll African Americans in research.

Table 1. Barriers and strategies to recruiting African Americans in clinical research.

| Barriers to recruitment | Strategies for improving minority participation |

| Fear, distrust, confidentiality, and privacy | Be transparent about the research process |

| Historical atrocities | Acknowledge past problems |

| Stigma associated with participating in research | Describe current safeguards to protect research participants |

| Peer and family concerns for the patient | Empower participants by letting them know that the decision to participate is theirs alone |

| Institutional sharing of personal data | Build rapport by conducting face-to-face interviews instead of phone interviews |

| Competing priorities and needs | Recognize the whole person. Respect other priorities in their life. |

| Socioeconomic stressors | Be flexible in scheduling and location of interviews |

| Family responsibilities | Create a resource book/directory to provide assistance with concerns raised during study participation |

| Work responsibilities | |

| Illness severity | |

| Protocol and system barriers | Allow protocol modifications (eg, shorter interviews or complete in more than one sitting) |

| Rigid or demanding research protocols | Offer alternatives for biospecimen collection |

| Limited clinic and research team engagement | |

| Clinic engagement as a barrier to recruitment | Develop and deepen relationships between clinic staff and research teams |

Figure 1. Recruiter focus group discussions, word frequency query.

Barriers to Participation

Fear, Distrust, Confidentiality and Privacy

Recruiters cited fear and distrust of medical research as a primary barrier to participation among African Americans. The words “mistrust” and “trust” were used 83 times throughout the focus group discussions. As shared by several recruiters, “…the number one reason Black women would give me … was they remember Tuskegee. There’s a distrust of the medical establishment.” This sentiment was heightened as they reflected on their experiences with older African Americans, as one recruiter stated, “The older population, they’re just suspicious of research in general…they might not know exactly what happened with the syphilis research … but they’ve heard something about it.”

In addition to awareness of historical abuses, recruiters shared the importance of being sensitive to current relationships between the community and medical/academic centers, as demonstrated by the following comment: “Just the stigmatism of the university itself, most of the African Americans are not wanting to be associated with the university as far as research is concerned.”

Recruiters also described concerns around divulging personal information and allowing recruiters in their home as a barrier, as illustrated by, “We can try to discuss confidentiality measures that we take with them, and even a lot of times that isn’t enough…They’ll say…I still don’t trust or believe this will be kept [confidential].” Likewise, as stated by one recruiter, ”People don’t want the interviewer in their home … so a barrier is finding a location that the person is able to get to… and in which we can keep confidentiality.” Also caregivers, who often serve as gatekeepers, may prohibit access to potential or consented research participants. One recruiter recalled, “That’s happened many times, where the person…wants to participate, but the family says no because they’re afraid of what they’re doing, they don’t understand it.” This fear was heightened when blood samples are requested, making it even more difficult to engage minorities in research. The key words “comfortable” and “confidentiality” were used 56 and 36 times respectively.

Strategies to Address Fear, Distrust, Confidentiality and Privacy

Recruiters reported being transparent as key to addressing fear, distrust and confidentiality. Specific strategies cited to ensure transparency included: 1) being open about the research process; 2) acknowledging historical wrongdoings in research; and 3) reiterating that participation was voluntary. As one recruiter stated, “Whenever you tell them that they have the control over it [research participation] …, that’s when you’ll have trust.” Recruiters can build trust and rapport with the potential participant by establishing the participant’s control over participating in research and ongoing communication throughout the process. Similarly, recruiters highlighted the importance of proactively acknowledging historical medical atrocities as illustrated in the following comment, “I think it’s great for us to be able to confess to those things that have actually happened, to say that we have been trained, that we do understand that those things have happened and we know that they’re not just these frivolous things.”

Competing Priorities and Needs

The most frequently used key word was “time,” which was mentioned 168 times. Recruiters identified extensive study processes as some of the most challenging factors to address when recruiting African Americans. For example, one recruiter stated “The study that I’m on now is very lengthy... When you tell them it’s 2.5, 3 hours, they tend to say, ‘Oh no, that’s too long, I don’t have time.’” Finding a convenient time to meet can be challenging as potential participants, especially those of lower socioeconomic status, have competing priorities such as child care, transportation, and limited time: “Especially with African American women, I find they are working 2 possibly 3 jobs, and they have children at home, and they just don’t have the time.” and “…a lot of them didn’t have transportation.”

Poverty, uncertain housing, lack of current contact information, competing priorities, unexpected distractions in the home, and illness are all significant issues that recruiters must consider when recruiting minorities into research. As one recruiter related, “They can’t think about doing an interview when they don’t know where they’re going to live the next day.”

Strategies to Address Competing Priorities and Needs

To address these competing priorities, recruiters noted the importance of listening and being able to identify resources to help support participants – essentially, acknowledging the whole person. For example, “In one of our research studies, we created a binder that had …. all kinds of information where we could…say …here’s a number you can call to get a crib, or [other] resources.” Others echoed similar strategies, such as “A lot of times, … they may go beyond the telephone interview with so many questions that kind of fall outside of our realm, so having the resources to provide to them is helpful” and “When people see that you’re trying to help them also, not just for the interview, but trying to help them with resources, outside of the interview, they’re more cooperative.”

Protocol and System Barriers

Rigid or demanding research protocols and other system barriers were also reported as challenges in recruiting African Americans in clinical research. Time constraints on the recruiting process can interfere with building a relationship with the potential participant as illustrated in the following quote, “I think sometimes, unfortunately in research studies you have the time set and you’re told this is how you are supposed to do it, but you’re missing that whole other part…of building rapport with people, getting to know them. And that builds trust.”

System barriers including lack of flexible schedules and complex research protocols that seem overwhelming or burdensome to the participant can create a barrier to recruitment.

Strategies to Address Protocol and System Barriers

Being mindful of participants’ time was critical to recruitment and retention, and willingness to modify schedules and research processes were important strategies to address concerns with time and comfort. For example: “I offer to do the study in 2 interviews, which sometimes works, or I offer it on a weekend or evening, whatever’s best for them” and “…they developed a shorter questionnaire. If people are like that’s such a long time, I come out with the shorter version, and people go oh, that would be a lot better.”

Offering alternative options, especially for bio specimen collection, was another effective strategy to retain participants. Some may feel uncomfortable about donating their blood but have less concern about donating saliva specimens. One recruiter noted: “Sometimes I tell people you can say yes to [donating] blood, and if you change your mind, by the time the phlebotomist calls you, you can let her know …, she’ll do the saliva.” Some recruiters identified lack of interest among participants based on how they felt physically or concerns about having strangers from the research team in their home. To overcome this barrier, when appropriate, some recruiters provided mail kits where the participant could do their own measurements, obtain their saliva swabs and send them back.

Clinic Engagement as a Barrier to Recruitment

From the recruiter’s perspective, for studies that recruit through medical practices, clinic personnel can have a significant impact on enrollment. One recruiter said, “… in our clinics… if the nurse is not interested in our study, then the participant is more likely to decline. Whereas if the nurse or the doctor goes in and they seem excited about the study, then the participant is more interested in talking to us.” Recruiters highlighted a lack of communication between the researcher/principal investigator and the clinic teams as a barriers to successful recruitment.

Strategies to address Clinic Engagement as a Barrier to Recruitment

Building rapport in the clinic was one strategy used by recruiters to encourage clinic staff to discuss the research project with patients. As one participant stated, “So important [to] have all the nurses and doctors trust you. Otherwise they’re not going to help you out when you’re recruiting their patients. That’s not something we were taught, we had to figure it out on our own, by bringing in cookies and doughnuts and stuff. So, I think clinic culture is … something that could be taught, along with how to address the culture of different patients.”

Needs and Recommendations

Recruiters identified several key training needs and recommendations to bolster minority participation in clinical research (Table 2). Increasing cross-cultural training, engaging in community outreach, understanding the role of the principal investigator and ongoing clinic education, support, and buy-in were all identified opportunities for improving recruitment success.

Table 2. Recruiter recommendations to increase African American’s participation in clinical research.

| Cultural competency and skillset building training |

| Incorporate cultural competency training to raise awareness around biases and cultural differences |

| Provide various training opportunities to build recruitment skillset |

| Use role playing and other techniques to improve understanding of cultural issues and to demonstrate how to engage and consent minority participants in a mutually empowering way |

| Community engagement and outreach |

| Provide education and resources about clinical research |

| Describe methods used to protect research participants |

| May be an opportunity to identify and reach potential research participants |

| Demonstrate researcher’s commitment to the community through ongoing engagement |

| Clinic and research team engagement |

| Understand the clinic culture and environment when recruiting through medical practices |

| Work with clinic staff to develop mutually workable protocols for patient enrollment |

| Educate and use meaningful strategies to engage clinic staff in the research study |

| Ensure engagement occurs at all levels between the research team and the clinic staff |

Cultural Competence and Skillset Building Training

Recruiters emphasized the need for cultural competency training to improve effectiveness with minorities. Cultural diversity training to improve self-awareness of biases and strategies to think “outside-the-box” were cited as important components for training. As shared by the recruiters, “I suggest some cultural competency [training], even if it is just a quiz … that’s short and sweet, but also shows that all of us have our own biases.” and “I definitely believe we need to have a cultural diversity seminar to discuss cultural differences…. with how to address the culture of different patients.” Recruiters noted that being a different race or ethnicity than the study participant posed a barrier. To overcome this barrier, recruiters used various strategies and skillsets to build rapport with the study participant, such as conducting face-to-face interviews instead of phone interviews and finding a common point of interest.

Others made recommendations on how training should be delivered, including role-playing to both understand culture and to demonstrate how to effectively gain consent from minority participants in a mutually empowering way. These sentiments are demonstrated in the following quotes: “…role playing, and watching, and critiquing, and understanding that, would be you know, maybe coupled with a lecture of some kind.” and “Definitely, delivery is so important. [If] you’re confident, and you seem like you know what you’re talking about, then more people are going to be willing to participate.”

Community Engagement and Outreach

Recruiters underscored the importance of providing the community with education and resources about clinical research to help mitigate distrust and lack of knowledge. Community outreach focused on information about safeguards for protecting participant privacy, were cited as ways to help ease concerns and encourage participation in research among minority populations. Recruiters also saw outreach efforts as an opportunity to identify potential candidates for the studies: “So there has to be an outlet where we can reach … the African American population, to give them the information, why we’re doing this, and what the purpose is.” The key word “information” was used 112 times, and was the second most frequently used term during the focus groups.

Additionally, investigator engagement that spans beyond the university can have a significant impact on recruitment and retention as exemplified by: “I find that the ones [Researchers] that are out there in the community, getting to know the people, … spending time with them, aren’t hard into academia. Those are the ones able to do the recruitment, whether they’re White or Black.”

Other recruiters highlighted that researchers/investigators who engaged with the community were more successful: “They want to know somebody that will stick around, somebody that they’re familiar with in their community” and “I think that’s huge having someone invested in the study that they know and trust.”

Clinic and Research Team Engagement

The importance of communication between clinical collaborators and researchers was cited as a critical factor in successful recruitment. Physicians, nurses, and researchers all play a pivotal role in facilitating contact between potential research participants and the recruiter. When study participants are recruited in the clinic setting, recruiters attributed much of their success to the enthusiasm and engagement of clinic staff, including the doctors and nurses as they share information about the study with potential participants.

Learning to manage and nurture the relationship with the clinic to overcome some of these challenges is an important strategy to win the support and engagement of clinic staff. Although recruiters found this a challenge they also saw this as an additional training opportunity on how to build rapport within the clinic and among the research and clinic personnel. The focus group participants recommended that researcher, clinician and staff must acknowledge the importance of the research to strengthen the ability to recruit African Americans and minorities into clinical research studies.

Discussion

Our focus groups revealed both challenges and opportunities for increasing the representation of African Americans in clinical and epidemiologic research. Recruiters can have a profound influence on whether an individual decides to take part in the research, yet little research has explored factors that influence participation from their perspective. Our study aimed to address this gap in the literature and offer recommendations on strengthening programs and resources designed to support non-physician research recruiters as they engage minorities in clinical research.

Barriers to Participation

The focus group participants discussed barriers to research participation, including the effects of psychosocial, cultural and economic factors, which have been reported previously as reasons for lower participation rates in research studies by African Americans. Fear and mistrust of research because of historical abuses in research and medical practice such as the Tuskegee syphilis study is deeply entrenched in African American communities and remain as prominent reasons that African Americans decide not to participate in research studies. Other key barriers include time and financial constraints, discomfort with sharing personal information or having a stranger in one’s home, race of the recruiter, and family members serving as gatekeepers and discouraging participation. In addition, lack of clinic and research team communication and engagement was also cited as a key barrier to ensuring effective recruitment of African Americans in research.

The identification of barriers, while clearly an important outcome of the focus groups, is the first step in reducing disparities in research resulting from lower participation of African Americans. The subsequent points discussed in the focus groups – strategies that recruiters employ to overcome barriers to participation and resources needed by recruiters to improve their effectiveness – have the potential for greater impact on increasing representation of African Americans in research studies.

Recommendations for Training

Recruiters shared the need for training in cultural diversity, implicit bias, and clinic and research team engagement. Such training, for both research personnel and clinic staff, should highlight the importance of minority participation. Role-playing was recommended as a training method to help individuals improve their recruitment skills and learn from each other. On-going feedback by other recruiters and investigators should enhance recruiters’ skills by improving their confidence and allowing them to share strategies for successful recruitment. With more practice, recruiters felt they would be more aware of, and responsive to, their own cultural biases and would become more comfortable explaining and answering questions about the study, consent documents and confidentiality concerns. Focus group members also recommend that recruiter training should emphasize the importance of developing good listening skills to help build rapport with potential participants, and help them identify concerns about research that a potential participant may not explicitly express.

Recognizing and Addressing Patient Needs and Priorities

Other recommendations centered on recognizing the whole person, rather than focusing on the individual simply as a study participant. Taking time to participate in research may not be a high priority in a life filled with other demands including working one or more jobs, caring for children or other family members or dealing with a medical condition. By recognizing these competing demands, the recruiter may offer alternatives that make it easier for an individual to participate in the study, including being available for interviews on evenings and weekends, offering shorter questionnaires or alternative options for bio-specimen collection, addressing limited literacy, and being prepared to provide additional resources to participants (e.g., social services, disease-specific information, etc). Focus group participants felt that offering study participants something of use to them was not only the right thing to do, but also reduced concerns that researchers were taking from the community without providing anything in return. The recruiters also emphasized the importance of making sure potential participants are empowered to make their own decision to take part in research. Shifting the perceived power balance from the recruiter to the participant may make them more likely to agree to participate.

Importance of Clinic and Community Engagement

This study highlights challenges associated with collaboration across health systems and the research enterprise. Clinical care and research should be complementary in academic health centers. Communication and training that is comprehensive and collaborative is critical to improving access to clinical research for minority populations. Moreover, a perceived lack of engagement by physicians and other clinic staff may indicate the need for streamlined procedures, more training, and clear language to support clinicians when they are asked to introduce a research study. Communication, training, and other support may be needed at all levels of the research recruitment process and must be part of a comprehensive initiative. From our findings, there may be a linkage between recruitment success and how potential participants are invited to participate in research.

An additional point made by the recruiters is that the most successful investigators are those who are actively engaged in the communities. This point is consistent with the growing emphasis on patient-centered outcomes research and community-engaged research, and echoes the opinions expressed by Wallerstein, et al. regarding the role of community-based participatory research in addressing health disparities.19,20 Although not stated in the context of community-engaged research, many of the strategies recommended by the recruiters to improve participation mirror those described by Wallerstein et al, namely acknowledging past and current trust issues, recognizing and respecting cultural differences, empowering study participants and being truly involved in the community.21

Strengths and Limitations

The most notable strength of our study was our focus on non-physician recruiters, who are often the first point of contact with potential study participants and, therefore, have a critical influence on overall response rates. Participants came from diverse geographic areas and all had enrolled African American study participants. The focus groups were conducted by an investigator who was not in a supervisory role for any of the recruiters, which should have fostered more candid sharing of opinions. Secondly, the findings from this study highlight key barriers and specific and innovative strategies non-physician research recruiters implement to overcome challenges associated with recruiting African American participants into clinical research. Strategies address multi-level barriers that impact minority enrollment rates. Another strength of this study is reflected in the capacity-building recommendations from study participants, which include developing content-specific trainings with modalities to build recruiter skills in cultural sensitivity, bias recognition, clinic engagement, and community outreach.

Our study also has some limitations. Notably, education level and years of experience were not captured in this study. Most focus group participants were currently involved in cancer-related epidemiologic studies, although most had previous experience in diverse study types. While many of the themes that arose from the focus groups are applicable to research studies in general, some concerns are specific to cancer, including challenges of recruiting participants when they are receiving chemotherapy or cultural beliefs surrounding cancer. For studies involving other conditions, concerns unique to that disease state could arise.

By design, we focused on barriers related to enrollment in observational epidemiologic studies, rather than clinical trials. There may be additional and distinct barriers to participation in clinical trials where there is greater potential direct benefit to participants but also greater treatment-associated risks and fears of possibly unproven treatments.

In addition, we focused only on African Americans and did not address recruitment challenges for other ethnic minorities. The challenges may be different for other minorities; for example, language barriers may be more prominent and trust issues may be more related to immigration concerns rather than historical abuses. Additional work is needed to understand barriers and develop strategies to improve representation of other minority groups in clinical research.

Future research is planned to specifically explore challenges in recruiting minorities in clinical trials, behavioral interventions, and bio-banking studies. Outcomes from the focus groups will be used to plan and develop culturally appropriate mechanisms to increase participation of minorities and particularly African Americans in research.

Conclusion

Well-documented barriers to research participation, including fear and mistrust and arduous and inflexible research protocols, persist as prominent concerns in recruitment of African Americans into research. Reviewing and revising protocols and system barriers to accommodate diverse patients and their needs may bolster minority recruitment and retention. However, according to recruiters, clinic communication, education, support and partnership with the research teams were strong predictors of minority recruitment success. This highlights a key opportunity to more effectively engage clinics and the research enterprise in beneficial and equitable collaborations to improve research participation. Providing training to research and clinic staff in topics such as community education, research engagement, diversity and cultural bias, and managing relationships between health systems and the research enterprise were recommended to improve communication and collaboration between patient care and research teams.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Duke Cancer Institute and the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA142081). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sydnee Crankshaw and Chamali Wickersham to the focus groups described in this manuscript.

References

- 1. Byrne MM, Tannenbaum SL, Glück S, Hurley J, Antoni M. Participation in cancer clinical trials: why are patients not participating? Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):116-126. 10.1177/0272989X13497264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720-2726. 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olshan AF, Perreault SD, Bradley L, et al. The healthy men study: design and recruitment considerations for environmental epidemiologic studies in male reproductive health. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(3):554-564. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ofstedal MB, Weir DR. Recruitment and retention of minority participants in the health and retirement study. Gerontologist. 2011;51(suppl 1):S8-S20. 10.1093/geront/gnq100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durant RW, Wenzel JA, Scarinci IC, et al. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to minority recruitment for clinical trials among cancer center leaders, investigators, research staff, and referring clinicians: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Cancer. 2014;120(suppl 7):1097-1105. 10.1002/cncr.28574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinto HA, McCaskill-Stevens W, Wolfe P, Marcus AC. Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8)(suppl):S78-S84. 10.1016/S1047-2797(00)00191-5 10.1016/S1047-2797(00)00191-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fenton L, Rigney M, Herbst RS. Clinical trial awareness, attitudes, and participation among patients with cancer and oncologists. Community Oncol. 2009;6(5):207-228. 10.1016/S1548-5315(11)70546-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hagiwara N, Berry-Bobovski L, Francis C, Ramsey L, Chapman RA, Albrecht TL. Unexpected findings in the exploration of African American underrepresentation in biospecimen collection and biobanks. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(3):580-587. 10.1007/s13187-013-0586-6 10.1007/s13187-013-0586-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. IOM (Institute of Medicine) Public Engagement and Clinical Trials: New Models and Disruptive Technologies: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fouad MN, Johnson R, Nagy MC, Person S, Partridge E. Adherence and retention in clinical trials: a community-based approach. Cancer. 2014;120(0 7):1106-1112. https:// doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.28572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537-546. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herring P, Montgomery S, Yancey AK, Williams D, Fraser G. Understanding the challenges in recruiting blacks to a longitudinal cohort study: the Adventist health study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3):423-430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moorman PG, Newman B, Millikan RC, Tse CK, Sandler DP. Participation rates in a case-control study: the impact of age, race, and race of interviewer. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(3):188-195. 10.1016/S1047-2797(98)00057-X 10.1016/S1047-2797(98)00057-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879-897. 10.1353/hpu.0.0323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hansen KM. The effects of incentives, interview length and interviewer characteristics on response rates in a CATI-study. Int J Public Opin Res. 2006;19(1):112-121. 10.1093/ijpor/edl022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis RE, Couper MP, Janz NK, Caldwell CH, Resnicow K. Interviewer effects in public health surveys. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(1):14-26. 10.1093/her/cyp046 10.1093/her/cyp046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312-323. 10.1177/1524839906289376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1)(suppl 1):S40-S46. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barrett N, Hawkins T, Wilder J, Ingraham K, Worthy V, Boyce X, Reyes R, Chirinos M, Wigfall P, Robinson W, Patierno S. Implementation of a health disparities and equity program at the Duke Cancer Institute. Oncology Issues. 2016; September-October:47-58.