Brugada syndrome (BrS) is primary electrical disorder characterized by ST segment elevation with right bundle branch block morphology in patients with apparent structurally normal hearts.[1] It predisposes affected individuals to ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation (VT/VF) and sudden cardiac death (SCD).[2] A number of studies have identified risk factors that are associated with a more malignant course of disease. These include male gender, syncope, a spontaneous type 1 ECG pattern, family history of SCD, family history of Brugada syndrome, loss-of-function mutations in the SCN5a gene, inducible VT/VF during programmed electrical stimulation. Of these risk factors, many studies have demonstrated that the presence of a spontaneous type 1 pattern is associated with a significantly higher risk of VT/VF or SCD, but other studies have demonstrated a lack of significant predictive value.

Three meta-analyses have addressed the prognostic value of a spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern. Firstly, Letsas, et al.[3] examined its predictive value in six studies involving 2219 asymptomatic patients only, demonstrating a 3.6-fold increase in the risk of future arrhythmic events. Secondly, Wu, et al.[4] examined only prospective studies (n = 8) that included 1150 patients, demonstrating a 4-fold increase in the risk. Finally, Gehi, et al.[5] examined also only prospective studies (n = 3) in 935 patients, demonstrating a relative risk of 4.7. In this study, we performed an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, which includes the largest number of studies and patient numbers.

PubMed and Embase were searched for studies that investigated the association between a spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern on the ECG and ventricular arrhythmias and SCD in Brugada syndrome. The following search terms were used for both databases: “Brugada syndrome spontaneous type 1”. The search period was from the beginning of the database through to 30th June 2017 without language restrictions. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) the study was a case-control, prospective or retrospective cohort study in human subjects with a Brugada phenotype; and (2) data on the relationship between a type 1 pattern and adverse events (appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks, VT/VF, and SCD) were reported.

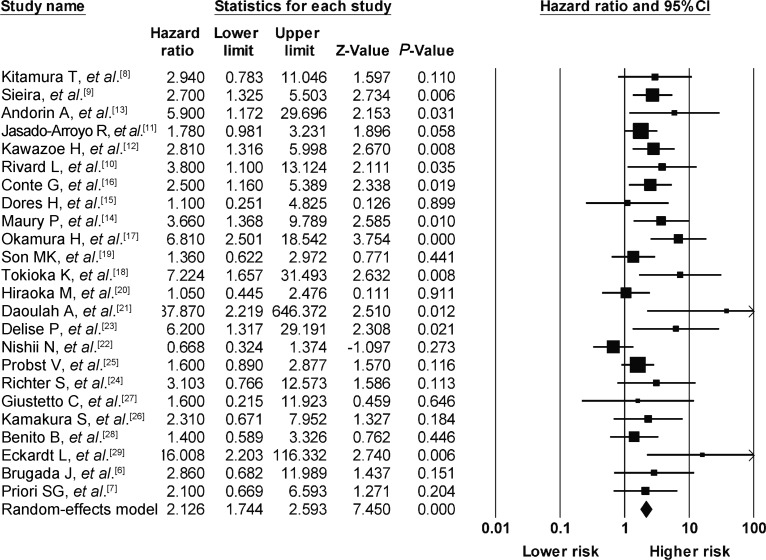

A total of 139 and 10 entries were retrieved from PubMed and Embase, respectively. After reference trawling and excluding overlapping populations, a total of 6561 Brugada patients from 24 studies were included.[6]–[29] The mean age was 44 ± 16 years and 73% of the patients were male, with a mean follow-up of 50 ± 36 months. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of these studies and the study populations. Quality analysis of the included studies by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was shown in Table 2. The main finding of our meta-analysis is that the presence of a spontaneous type 1 pattern on the ECG confers 2.3 times the risk of ventricular arrhythmias or SCD in Brugada syndrome. There was a low level of heterogeneity (I2 = 42%) with significant publication bias (Kendall's tau = 0.37, P < 0.05).

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis.

| Studies | Study design | Sample size (n) | Age | Males | Endpoints | Follow-up duration (months) | Univariate or multivariate | Multivariate variables |

| Kitamura T, et al.[8] | R | 304 | 30 | 169 | VT/VF | 91 | U | - |

| Sieira J, et al.[9] | P | 400 | 41 | 233 | SCD + ICD Shock | 81 | U | - |

| Andorin A, et al.[13] | R | 106 | 11 | 58 | SCD + ICD Shock + VT/VF | 54 | M | Age and ICD |

| Casado-Arroyo R, et al.[11] | P | 447 | 45 | 336 | SCD + ICD Shock + VT/VF | 50 | U | - |

| Kawazoe H, et al.[12] | R | 143 | 46 | 140 | VF | 83 | U | - |

| Rivard L, et al.[10] | R | 105 | 46 | 83 | aSCD + appropriate ICD shocks | 60 | M | Max Tp-e and QRS in lead 6 |

| Conte G, et al.[16] | P | 176 | 43 | 118 | Appropriate ICD shocks | 84 | U | - |

| Dores H, et al.[15] | R | 55 | 42 | 30 | Appropriate ICD shocks | 74 | U | - |

| Maury P, et al.[14] | R | 325 | 47 | 258 | SCD + appropriate ICD shocks | 48 | M | Sp1 ST elevation, SCN5A mutation, family history of SCD, QRS duration, Max Tp-e |

| Okamura H, et al.[17] | R | 218 | 46 | 211 | SCD + appropriate ICD shocks | 78 | M | Sp1, Syncope, inducibility of VF (PES+) |

| Son MK, et al.[19] | R | 69 | 48 | 68 | Appropriate/inappropriate ICD shocks | 57 | M | Age, presence of palpitations, sVT before implantation of ICD |

| Tokioka K, et al.[18] | R | 246 | 48 | 236 | SCD + ICD Shock + VF | 45 | U | - |

| Hiraoka M, et al.[20] | P | 460 | 52 | 432 | SCD + VF | 43 | U | - |

| Daoulah A, et al.[21] | R | 25 | 32 | 25 | Appropriate ICD shocks | 41 | NA | - |

| Delise P, et al.[23] | P | 320 | 43 | 258 | SCD + VF | 40 | M | Syncope, basal type 1 ECG |

| Nishii N, et al.[22] | P | 108 | 49 | 10 | Appropriate ICD shocks | 72 | U | - |

| Probst V, et al.[25] | R | 1029 | 45 | 745 | SCD + appropriate ICD shocks | 32 | M | Symptoms at diagnosis (aSCD/asymptomatic/syncope), Sp1, age, gender, EPS |

| Richter S, et al.[24] | P | 186 | 43 | 115 | aSCD + appropriate ICD shocks + VF | 57 | U | |

| Giustetto C, et al.[27] | P | 166 | 42 | 138 | aSCD + appropriate ICD shocks + VF | 30 | U | - |

| Kamakura S, et al.[26] | R | 330 | 51 | 315 | SCD + VF | 49 | U | - |

| Benito B, et al.[28] | P | 384 | 46 | 272 | SCD + VF | 58 | M | Gender, previous AF, symptoms at diagnosis (syncope, aSCD), Sp1, EPS |

| Eckardt L, et al.[29] | R | 212 | 45 | 152 | Appropriate ICD shocks + VF | 40 | U | - |

| Brugada J, et al.[6] | P | 547 | 41 | 408 | SCD + VF | 24 | M | Gender, Sp1, syncope, EPS (inducible) |

| Priori SG, et al.[7] | P | 200 | 41 | 152 | Cardiac arrest | 34 | U | - |

AF: atrial fibrillation; aICD: appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator; aSCD: aborted sudden cardiac death; EPS: electrophysiological study; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; M: multivariate; NA: not available; P: prospective; R: retrospective; sVT: sustained ventricular tachycardia; U: univariate; VF: ventricular fibrillation.

Table 2. NOS risk of bias scale for included cohort studies.

| Studies | Selection |

Outcome |

|||||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at start of study | Comparability | Assessment of outcome | Adequacy of duration of follow-up | Adequacy of completeness of follow-up | Total score (0–9) | |

| Priori SG, et al.[7] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Brugada J, et al.[6] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Benito B, et al.[28] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Delise P, et al.[23] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Probst V, et al.[25] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Nishii N, et al.[22] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Daoulah A, et al.[21] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Hiraoka M, et al.[20] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Son MK, et al.[19] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (gender) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Tokioka K, et al.[18] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Conte G, et al.[16] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Dores H, et al.[15] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Okamura H, et al.[17] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Andorin A, et al.[13] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Casado-Arroyo R, et al.[11] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kawazoe H, et al.[12] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Rivard L, et al.[10] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 (gender) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Kitamura T, et al.[8] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 (gender, family history of SCD) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Sieira, et al.[9] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 (gender) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa scale; SCD: sudden cardiac death.

The ECG is a simple and non-invasive test that provides information on cardiac electrophysiological properties of the test subjects. A spontaneous Brugada pattern indicates the presence of both depolarization and repolarization abnormalities at baseline, which represent substrates for re-entrant arrhythmogenesis.[30]–[32] This is in contrast to the presence of a type 2 or type 3 Brugada pattern, which can be converted to a type 1 pattern using drug challenge.[33] In addition to this type 1 characteristic pattern, detailed analyses of conduction and repolarization intervals from the 12-lead ECG can aid risk stratification.[34]–[37] For example, a recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that prolonged Tpeak–Tend intervals, which represent a higher dispersion of repolarization, whilst another showed that fragmented QRS complex,[38] which indicates dispersion of conduction, are associated with higher risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in Brugada syndrome. Our meta-analysis shows patients with spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern are at a high risk of adverse events. The ECG is a valuable tool that can aid clinicians to identify such high-risk individuals, who will require primary prevention by implantable cardioverter-defibrillator insertion.

Figure 1. Forest plot demonstrating the hazard ratios for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death with a spontaneous type 1 Brugada pattern.

Acknowledgments

Tse G and Wong SH thank the Croucher Foundation of Hong Kong for the support of their clinical assistant professorships.

References

- 1.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tse G, Liu T, Li KH, et al. Electrophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: insights from pre-clinical and clinical studies. Front Physiol. 2016;7:467. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Letsas KP, Liu T, Shao Q, et al. Meta-analysis on risk stratification of asymptomatic individuals with the brugada phenotype. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu W, Tian L, Ke J, et al. Risk factors for cardiac events in patients with Brugada syndrome: A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. 2016;95:e4214. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gehi AK, Duong TD, Metz LD, et al. Risk stratification of individuals with the Brugada electrocardiogram: a meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:577–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Determinants of sudden cardiac death in individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and no previous cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108:3092–3096. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000104568.13957.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M, et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation. 2002;105:1342–1347. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitamura T, Fukamizu S, Kawamura I, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term prognosis of senior patients with Brugada syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sieira J, Conte G, Ciconte G, et al. A score model to predict risk of events in patients with Brugada Syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1756–1763. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivard L, Roux A, Nault I, et al. Predictors of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in a quebec cohort with Brugada syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:1355 e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casado-Arroyo R, Berne P, Rao JY, et al. Long-term trends in newly diagnosed Brugada syndrome: implications for risk stratification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawazoe H, Nakano Y, Ochi H, et al. Risk stratification of ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome using noninvasive scoring methods. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andorin A, Behr ER, Denjoy I, et al. Impact of clinical and genetic findings on the management of young patients with Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1274–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maury P, Sacher F, Gourraud JB, et al. Increased Tpeak-Tend interval is highly and independently related to arrhythmic events in Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2469–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dores H, Reis Santos K, Adragao P, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with Brugada syndrome and an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator. Rev Port Cardiol. 2015;34:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conte G, Sieira J, Ciconte G, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura H, Kamakura T, Morita H, et al. Risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome without previous cardiac arrest-prognostic value of combined risk factors. Circ J. 2015;79:310–317. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokioka K, Kusano KF, Morita H, et al. Electrocardiographic parameters and fatal arrhythmic events in patients with Brugada syndrome: combination of depolarization and repolarization abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2131–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Son MK, Byeon K, Park SJ, et al. Prognosis after implantation of cardioverter-defibrillators in Korean patients with Brugada syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:37–45. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiraoka M, Takagi M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Prognosis and risk stratification of young adults with Brugada syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2013;46:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daoulah A, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Ocheltree AH, et al. Outcome after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: the gulf Brugada syndrome registry. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishii N, Ogawa M, Morita H, et al. SCN5A mutation is associated with early and frequent recurrence of ventricular fibrillation in patients with Brugada syndrome. Circ J. 2010;74:2572–2578. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delise P, Allocca G, Marras E, et al. Risk stratification in individuals with the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern without previous cardiac arrest: usefulness of a combined clinical and electrophysiologic approach. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:169–176. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter S, Sarkozy A, Paparella G, et al. Number of electrocardiogram leads displaying the diagnostic coved-type pattern in Brugada syndrome: a diagnostic consensus criterion to be revised. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1357–1364. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635–643. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamakura S, Ohe T, Nakazawa K, et al. Long-term prognosis of probands with Brugada-pattern ST-elevation in leads V1-V3. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:495–503. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.816892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giustetto C, Drago S, Demarchi PG, et al. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009;11:507–513. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benito B, Sarkozy A, Mont L, et al. Gender differences in clinical manifestations of Brugada syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1567–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, et al. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257–263. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153267.21278.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tse G, Wong ST, Tse V, Yeo JM. Depolarization vs. repolarization: what is the mechanism of ventricular arrhythmogenesis underlying sodium channel haploinsufficiency in mouse hearts? Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2016;218:234–235. doi: 10.1111/apha.12694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tse G, Wong ST, Tse V, Yeo JM. Variability in local action potential durations, dispersion of repolarization and wavelength restitution in aged wild-type and Scn5a+/− mouse hearts modelling human Brugada syndrome. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:930–931. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tse G, Wong ST, Tse V, Yeo JM. Determination of action potential wavelength restitution in Scn5a+/− mouse hearts modelling human Brugada syndrome. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14:595–596. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayes de Luna A, Brugada J, Baranchuk A, et al. Current electrocardiographic criteria for diagnosis of Brugada pattern: a consensus report. J Electrocardiol. 2012;45:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tse G. Both transmural dispersion of repolarization and of refractoriness are poor predictors of arrhythmogenicity: a role for iCEB (QT/QRS)? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:813–814. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tse G. Novel conduction-repolarization indices for the stratification of arrhythmic risk. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:811–812. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tse G, Yan BP. Traditional and novel electrocardiographic conduction and repolarization markers of sudden cardiac death. Europace. 2017;19:712–721. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse G. (Tpeak-Tend)/QRS and (Tpeak-Tend)/(QT × QRS): novel markers for predicting arrhythmic risk in the Brugada syndrome. Europace. 2017;19:696. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meng L, Letsas KP, Baranchuk A, et al. Fragmented QRS as an electrocardiographic predictor for arrhythmic events in patients with Brugada syndrome: a meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:678. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]