Summary

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic and poly‐aetiological autoimmune disease characterized by the production of antibodies to autologous double‐stranded DNA (dsDNA) which serve as diagnostic and prognostic markers. The defective clearance of apoptotic material, together with neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), provides abundant chromatin or self‐dsDNA to trigger the production of anti‐dsDNA antibodies, although the mechanisms remain to be elucidated. In SLE patients, the immune complex (IC) of dsDNA and its autoantibodies trigger the robust type I interferon (IFN‐I) production through intracellular DNA sensors, which drives the adaptive immune system to break down self‐tolerance. In this review, we will discuss the potential resources of self‐dsDNA, the mechanisms of self‐dsDNA‐mediated inflammation through various DNA sensors and its functions in SLE pathogenesis.

Keywords: autoantibody, DNA sensors, IFN‐I, self‐dsDNA, SLE

Introduction

The immune system maintains a delicate balance between the immune response against pathogen invasion and immune tolerance to self‐antigen, so‐called immune homoeostasis. The defective immune response leads to infection and tumour growth, while an overwhelming immune response causes autoimmune diseases. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by the production of antibodies to various nuclear antigens, named anti‐nuclear antibodies (ANAs). Among these ANAs, anti‐double‐stranded DNA (anti‐dsDNA) antibodies serve as diagnostic and prognostic markers and play important roles in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis (LN), a major cause of morbidity and mortality of SLE 1. Since the 1970s, the level of ANA or anti‐dsDNA antibody has been accepted in SLE classification criteria by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) 1. Recently, significant effort has been taken to understand the function of self‐dsDNA in SLE pathogenesis and how it triggers autoimmunity in SLE patients 2, 3.

There are multiple mechanisms to keep self‐dsDNA away from immune recognition; for example, dsDNA is restricted in nucleus and mitochondria in cells and degraded quickly by DNases in cytoplasm and endosomes. A defect in these mechanisms, for instance, inefficient clearance of apoptotic cell debris and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), results in the accumulation of self‐dsDNA 4, 5. Self‐dsDNA is involved in the initiation and pathogenesis of SLE through different mechanisms. To initiate autoimmune diseases, the presence of dsDNA in sites of immune privilege is required to break the tolerance to autoantigen and to induce autoantibody production. Meanwhile, apoptotic cell‐derived self‐dsDNA in the germinal centre (GC) of SLE patients may be presented by follicular dendritic cells as antigen to autoreactive B cells, providing the survival signal to prevent those B cells being eliminated 6. Regarding the pathogenesis of SLE, self‐dsDNA, together with autoantibodies, contributes to multiple clinical features of SLE, including immune complex (IC)‐mediated tissue damage, inflammatory cytokine production and the interferon (IFN) signature. Of note, self‐dsDNA is sensed mainly by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) through various DNA sensors, leading to robust type I interferon (IFN‐I) production 7. IFN‐I has many immune functions, from stimulating differentiation and maturation of dendritic cells to activating T cells and promoting antibody production by B cells, which highlights the critical function of IFN‐I in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, especially SLE 7, 8. In this review, we will summarize the knowledge concerning the mechanisms of self‐dsDNA‐mediated inflammation through DNA sensors and its functions in SLE pathogenesis, which may lead to the discovery of new therapeutic strategies of SLE.

Cell death and self‐dsDNA in SLE

The aetiology of SLE is multi‐factorial, including genetic and environmental factors which lead to presentation of autoantigen, production of autoantibody, chronic inflammation and tissue damage 3. Self‐dsDNA is restricted strictly to the nucleus and mitochondria, but could be released from these organelles in the process of cell death 9. Cell death, including apoptosis, necrosis and NETosis (special cell death of neutrophil through NETs), is the major potential resource of self‐dsDNA which activates the immune system and leads finally to autoimmune disease 10.

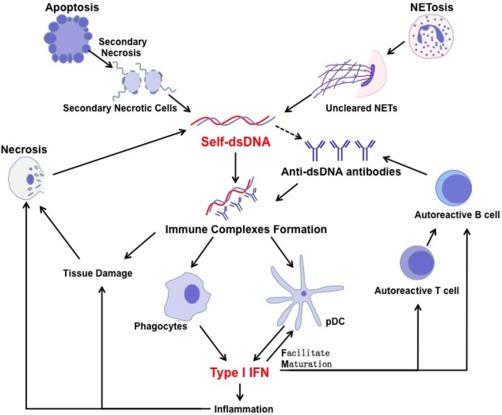

Apoptosis is also called programmed cell death, which is crucial to maintain tissue homeostasis in development and ageing. The process of apoptosis typically includes cell shrinkage, cytoskeleton remodelling, chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, plasma membrane blebbing and apoptotic body formation 11. Normally, apoptotic cells are phagocytosed immediately by phagocytes and degraded within the lysosomes without causing an inflammation and immune response. Indeed, the integrity of the cellular membrane is well maintained, and engulfing phagocytes secrete anti‐inflammatory cytokines 11. However, apoptotic cells which are not cleared quickly and efficiently undergo secondary necrosis, accompanied by rupture of the cell membrane and subsequent release of pathogenic intracellular contents, including self‐dsDNA 12. It is noteworthy that primary necrosis triggered by exogenous factors also leads to the release of intracellular material and contributes to the development of autoimmune diseases 13, 14. NETosis is a special cell death executed by neutrophils, in which nuclear DNA, histones and granular anti‐microbial proteins are extruded from the cells forming NETs 15. Moreover, other types of cell, such as eosinophils and mast cells, are reported to undergo cell death by a similar mechanism. In this regard, NETosis is not limited to neutrophils, but represents a new class of cell death with extracellular traps release 16. In the physiological scenario, monocyte‐derived macrophages clear NETs efficiently, and this process is facilitated by the extracellular preprocessing of NETs by DNase I and C1q 17. After being ingested by macrophages, NETs are transported via phagosomes into lysosomes for degradation. The uptake of NETs by macrophages does not induce proinflammatory cytokine secretion, indicating that this process is immunologically silent 17. A defect in this process will cause the accumulation of autoantigens including dsDNA 18, 19, 20, although another study has shown a protective role of NETs in SLE 21. Recently, emerging evidence indicates that self‐dsDNA released from cell death plays a crucial role in SLE pathogenesis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Self‐dsDNA involved in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In SLE patients, the clearance of apoptosis, necrosis and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) is defective which is the major resource of self‐dsDNA to induce autoantibody production with unrevealed mechanism. Anti‐dsDNA antibodies are produced by autoreactive B cells with the help of autoreactive T cells. Immune complex of dsDNA and its autoantibody triggers the robust type I interferon (IFN‐I) production through various intercellular DNA sensors in phagocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC). IFN‐I is the driving force in SLE pathogenesis by participating in inflammatory reactions, tissue damage, DC maturation and activation of autoreactive T and B cells.

Self‐dsDNA released by apoptotic cells

Physiologically, clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes relies directly and indirectly upon phosphatidylserine (PS) 11. PS on the surface of apoptotic cells could be recognized by phagocytes via its receptors, such as T cell immunoglobulin (Ig) and mucin domain‐containing molecule 4 (Tim4). Meanwhile, PS could interact with phagocytes indirectly through bridging proteins, such as complement C1q, the milk fat globule EGF factor 8 (MFG‐E8) or growth arrest‐specific 6 (Gas6) 4, 11. The binding of PS with its receptor induces rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and internalization of apoptotic cells 4, 11. Tim‐4‐deficient mice show the phenotype of presentation of anti‐dsDNA antibodies, and elevated B and T cell activation 22. A deficiency of C1q or MFG‐E8 in the murine model results in remarkable autoimmunity, as indicated by anti‐dsDNA autoantibodies and glomerulonephritis 23, 24. Mice lacking the membrane tyrosine kinase c‐mer, a receptor on phagocytes for bridging Gas6 to PS, have impaired clearance of apoptotic cells and develop progressive lupus‐like autoimmunity symptoms with antibodies to chromatin and DNA 25. DNase II is located in the lysosomes of phagocytes, where it degrades DNA from engulfed apoptotic cells. DNase II knock‐out mouse is embryonically lethal; however, it could be viable if the IFN receptor I gene is deleted, with chronic polyarthritis resembling human rheumatoid arthritis rather than symptoms of SLE 26.

Consistent with findings from animal studies, emerging evidence shows that the clearance of apoptotic cells is impaired in SLE patients. Gaipl and colleagues found that CD34+ CD45+ haematopoietic stem cells isolated from peripheral blood of SLE patients show reduced differentiation to macrophages when stimulated with granulocyte–macrophage colony‐stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) in vitro 27. Macrophages from SLE patients cultured in vitro are smaller, with impaired adhesion and decreased phagocytic capacity for autologous apoptotic material 28, 29. More direct evidence of the involvement of clearance deficiency in the aetiology of SLE comes from lymph node biopsy. Normally, apoptotic cells in lymph nodes are engulfed and degraded by so‐called tingible body macrophages (TBMs), which are located in GCs in close proximity to follicular dendritic cells 6. However, TBMs are smaller in SLE patients. The proportion of macrophages containing ingested material of apoptotic cell is remarkably reduced, suggesting that these cells have a defective capacity to clear apoptotic cells, as the resulting nuclear remnants of apoptotic cells are accumulated in GCs 6. Abnormally activated or overwhelmed macrophages are also associated with dysregulated T cell functions and autoantibody production, which is found in some SLE patients, suggesting a unique role of macrophage in SLE pathogenesis 30. Taken together, inefficient clearance of apoptotic cells is one major cause of SLE, the consequence of which is the constitutive presence of autoantigens including DNA.

Self‐dsDNA released through NETs

The clearance of NETs in vivo depends highly upon DNase I, which is the major DNA endonuclease in circulation. DNase I‐deficient mice develop the classical symptoms of SLE, such as the presence of ANAs, including anti‐dsDNA antibodies, IC in glomeruli and glomerulonephritis 18. DNase I activity in serum is actually lower in SLE patients than in healthy individuals 18. IC‐containing neutrophil‐derived anti‐microbial peptides, self‐dsDNA and their specific antibodies are found in SLE patients, suggesting that accumulation of self‐dsDNA could be because the capability of DNase I has been over‐run, which might worsen when DNase I activity is impaired. 18, 31. Moreover, DNase I specific inhibitors could prevent NETs degradation 31. Anti‐NET antibodies, C1q, anti‐microbial peptide LL‐37 or high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) binding to NETs could also interrupt NETs degradation mediated by DNase I and contribute to the pathogenesis of SLE 5, 32, 33.

As discussed above, emerging evidence implies that impaired DNase I activity leads to defective degradation of NETs and release of self‐dsDNA, which subsequently promotes autoantibody production, inflammation and tissue damage. Additionally, the accumulation of DNA may also be attributed to the enhanced capacity for NETosis in SLE patients. Neutrophils from lupus mice and SLE patients undergo NETosis more easily than those from healthy controls 5, 19, 20. Neutrophils exposed to ribonucleoprotein immune complexes are liable to undergo NETosis through the induction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) 34. Moreover, SLE patients have a distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils, low‐density granulocytes (LDGs) 35, which have an enhanced capacity of forming NETs 20 and synthesizing mitochondrial ROS 34. Taken together, all these studies provide convincing evidence that NETosis is one of the major sources of self‐dsDNA, and a defect in NETs clearance plays an important role in SLE pathogenesis.

Self‐dsDNA released by necrosis

Necrosis is considered to be an accidental cell death mechanism, which is triggered usually by external factors such as trauma or infection, resulting in the loss of cell membrane integrity and an uncontrolled release of intracellular material, including self‐dsDNA, into the extracellular space 15. Even the aetiological role of necrosis in SLE pathogenesis is controversial; it is accepted that trauma and infection‐associated necrosis aggravates the pre‐existing SLE 13, 14, 36. In addition, extremely harsh physical conditions such as anoxia or high concentrations of pro‐oxidants could also cause necrosis in vivo, which is a common condition during the pathological process of SLE. Under these conditions, necrosis could be recognized as one part of the vicious loop of the disease 37; however, its function in the aetiology of SLE needs to be studied further.

Role of dsDNA in antibody production

Pathogen‐derived exogenous DNA is immunogenic, but the immunogenicity of self‐dsDNA remains to be elucidated 9. Bacterial dsDNA with unmethylated cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) motifs induces anti‐dsDNA antibodies in both wild‐type and lupus mice. Whereas wild‐type mice produce antibodies specific for bacterial DNA, lupus mice produce antibodies not only against bacterial DNA but are also cross‐reactive to mammalian DNA 38, 39. Further studies have revealed that anti‐dsDNA antibodies specific for bacterial DNA target mainly its base sequential determinants; however, antibodies against self‐dsDNA in SLE target its deoxyribose phosphodiester backbone 1, 40. Mammalian dsDNA is an immunogenic hapten for activating B cells when combined with an appropriate stimulus as the co‐stimulatory factor of T helper cells or B cells. For instance, DNA‐binding proteins derived from pathogens may enhance the immunogenicity of self‐dsDNA, resulting in anti‐dsDNA antibody production. Fus1, from the parasitic protozoan Trypanosoma cvuzi and T antigen from polyomavirus, could render mammalian DNA immunogenic in wild‐type mice and induce the production of anti‐dsDNA antibodies 41, 42. Anti‐microbial peptide LL37 also could bind to dsDNA to activate Toll‐like receptor 9 (TLR‐9) signalling in pDCs, leading to uncontrolled IFN production that drives autoimmune skin inflammation 43.

These studies reveal that binding of mammalian DNA with immunogenic polypeptides increases immunogenicity of DNA significantly and could induce anti‐dsDNA antibody production in vivo. However, it is also observed that under some circumstances autologous DNA alone is strongly immunogenic without forming complexes with immunogenic peptides. Ultraviolet light (UV), known as the major triggering factor of skin lesion in SLE patients, damages DNA directly and activates the immune response through myeloid dendritic cells 44. Meanwhile, self‐dsDNA damaged by ROS during NETosis is highly immunogenic 34. The hypomethylated DNA from apoptotic cells is sufficient to induce anti‐dsDNA antibodies and lupus‐like autoimmune disease, even in SLE non‐susceptible mice 45. Although how DNA is demethylated and released during the apoptosis process is unclear, the altered modification of DNA during cell death has proved to be crucial for the induction of anti‐dsDNA antibody.

The mechanism of how anti‐dsDNA antibody is produced in SLE patients remains elusive. Immunogenic self‐DNA or the DNA–polypeptide complex may serve as an antigen. Other studies focus upon the breakdown of immune tolerance towards autoantigen by T or B cells. Autoreactive T helper type 0 (Th0) and Th1 cells isolated from SLE patients, which are specific for histone, could induce anti‐dsDNA antibody production when co‐cultured with autologous B cells in vitro 46. Meanwhile, autoreactive Th2 could cause a lupus‐like symptom with anti‐dsDNA antibody production after being transferred into normal recipient mice 47. Although it is well accepted that, in healthy individuals, autoreactive B cells exist in vivo without any clinical symptoms, how this special B cell population is generated and maintained is not yet understood fully. Studies show that compared with those in healthy individuals, autoreactive B cells in SLE patients are less anergized 48. One potential explanation is that genetic and environmental factors break down B cell tolerance, so autoreactive B cells could pass the negative checkpoint unimpeded, therefore participating in GC formation and developing into memory B cells and plasma cells in SLE patients 49.

IFN‐I is produced by innate immune cells in the presence of viral and bacterial nuclear acids, as well as immunogenic self‐DNA. IFN‐I could promote the functions of autoreactive T and B cells. It is reported that IFN‐I significantly lowers the threshold of T and B cell activation 8, prolongs the survival of activated T cells and promotes memory T cell development 50. Additionally, IFN‐I suppresses regulatory T cell (Treg) functions and increases Th17 differentiation, which will result in an expansion of autoreactive T cells 51, 52. With regard to B cells, IFN‐I induces the production of B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS), supporting B cell activation and differentiation through the B cell receptor, as well as facilitating Ig class‐switching to generate potentially pathogenic autoantibodies 53, 54.

Once anti‐dsDNA antibody is produced, it binds to its target DNA to form the IC and circulates in blood or, even worse, deposits in tissues. Antigen‐presenting cells (APC) such as conventional dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages and pDCs internalize these IC and secret a great deal of proinflammatory cytokines, mainly IFN‐I. The anti‐dsDNA antibody plays a critical role in internalization of self‐DNA‐contained complexes via binding to Fcγ surface receptor II (FcγRII) on the cell surface of APC 55, 56. Moreover, anti‐dsDNA antibodies also bind to antigens, expressed in glomerular basement membrane and vascular endothelium, to initiate tissue damage and organ pathogenesis 57, 58. In conclusion, anti‐dsDNA antibodies participate in SLE pathogenesis by forming IC, thereby promoting self‐dsDNA cellular uptake by APC to activate IFN‐I production through DNA sensors.

DNA sensors and related signal pathways

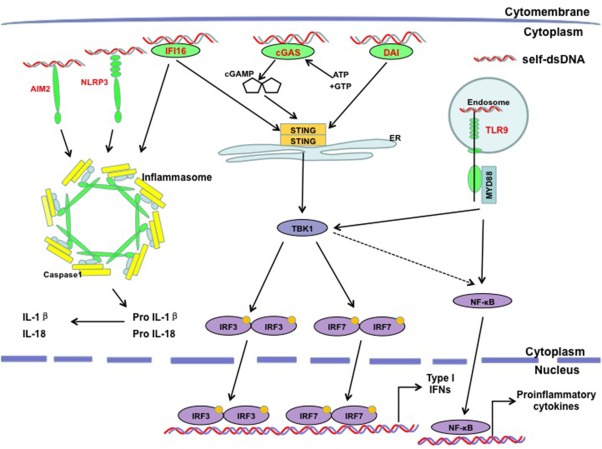

Foreign DNA, as well as pathogenic self‐DNA, is recognized by the immune system via DNA sensors in cytoplasm to activate downstream signal pathways for the immune response. Many DNA sensors have been identified, including TLR‐9 59, cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (GMP–AMP) synthase (cGAS) 60, DNA‐dependent activator of IFN‐regulatory factors (DAI) 61, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) 62, gamma‐IFN‐inducible protein 16 (IFI16) 62, nucleotide‐binding domain leucine‐rich repeat containing protein family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) 63, DEAD/H‐box helicase 41 (DDX41) 64 and meiotic recombination 11 (Mre11) 65. Upon binding of these DNA sensors with their ligands, respectively, signal pathways are activated, which include TLR‐9‐dependent, stimulator of interferon genes (STING)‐dependent and inflammasome‐dependent pathways for IFN‐I and proinflammatory cytokine production (Fig. 2). In physiological conditions these intracellular sensors and related pathways are regulated tightly in order to prevent the development of autoimmunity. However, in SLE patients, the presence of excessive self‐dsDNA triggers abnormal immune responses and breakdown of self‐tolerance through these sensors 66.

Figure 2.

Cytosolic DNA sensors and their signalling pathways in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Self‐dsDNA stimulates cytosolic DNA sensor‐dependent signal pathways for type I interferon (IFN‐I) and proinflammatory cytokines production. Many DNA sensors have been proven to be associated with the pathogenesis of SLE, mainly including Toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐9, cyclic growth arrest‐specific 6 (cGAS), DNA‐dependent activator of IFN‐regulatory factors (DAI), absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), gamma‐interferon inducible protein‐16 (IFI16) and nucleotide‐binding domain leucine‐rich repeat containing protein family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) to activate different signal pathways: TLR‐9‐dependent, stimulator of IFN genes (STING)‐dependent and inflammasome‐dependent pathways.

TLR‐9‐dependent signal pathway

TLRs are a major family of pattern recognition receptors in the innate immune system, responsible for activating the immune defence against a wide range of microbial pathogens 67. In particular, TLR‐9 is located in endosomes which recognize bacterial unmethylated CpG‐rich DNA and also endogenous nuclear acids, particularly SLE‐associated self‐DNA 68. Once TLR‐9 binds to intracellular DNA a downstream signal pathway is activated, which utilizes the main adaptor molecule myeloid‐differentiation primary response protein‐88 (MyD88) and leads to the activation of key transcriptional factors such as the IFN regulatory factor (IRF) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB). These two transcriptional factors control the production of IFN‐I and proinflammatory cytokines, respectively 69. TLR‐9 serves as the potent sensor to activate pDCs and naive B cells directly (together with B cell receptors). It also activates memory B cells, GC B cells and T cells indirectly through mediating the maturation of APCs in human and mouse 59.

While the role of TLR‐9 in viral infection has been studied extensively, the function of TLR‐9 in SLE is still under debate. Some studies find that self‐DNA can act as an endogenous antigen that induces autoantibody production through TLR‐9. SLE sera or IC‐containing self‐DNA can activate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), B cells and pDCs isolated from mouse through TLR‐9 59. Inhibition of TLR‐9 signalling in B cells by siRNA reduces the production of anti‐dsDNA antibodies and consequently ameliorates the SLE syndrome in the murine model 70. Moreover, TLR‐9‐deficient B cells specific for dsDNA are defective in class‐switching to pathogenic IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes 71. In addition, the deletion of Tlr9 in the MRL/Mplpr/lpr mouse reduces anti‐dsDNA and anti‐chromatin antibody production. Consistently, this decrease in antibody titres has been implied in several studies using different TLR‐9‐deficient lupus‐prone mouse models 71, 72, 73. Studies with human samples have indicated that the TLR9 mRNA level in PBMCs of SLE patients is higher than that in healthy individuals, which is correlated with a higher IFN‐α level 74. The TLR‐9 protein level is also elevated consistently in monocytes, T and B cells in SLE patients 75. Furthermore, the TLR‐9 protein level varies during different stages of SLE. Patients with an active phase of SLE have a higher TLR‐9 protein level in B cells compared with either patients with inactive SLE or healthy individuals 75, even though one study reported no correlation between disease activity and TLR‐9 protein level 59. Collectively, these studies provide evidence that the TLR‐9 signalling pathway may participate positively in SLE pathogenesis.

Emerging evidence suggests a protective role of TLR‐9 in SLE pathogenesis. Although antibody titres have been reduced in TLR‐9‐deficient lupus mice, as discussed above, more severe lupus symptom‐associated manifestations, including glomerulonephritis, immune complex deposition and T cell activation, are observed, accompanied by aberrant TLR‐7 activation. Interestingly, the exacerbation of disease in TLR‐9‐deficient lupus mice can be abrogated totally when Tlr7 is deleted 71, 76. Further study shows that in steady state, a multi‐transmembrane ER resident protein UNC93B1, which is needed for both TLR‐7 and TLR‐9 signalling, engages TLR‐9 preferentially but controls TLR‐7 activation 77. Another study shows that TLR‐9 protein can inhibit TLR‐7 through direct physical interaction 78. All these studies may explain the phenotype mentioned in TLR‐9‐deficient lupus mice. Contrary to the function of TLR‐9 in B cells, pDC from SLE patients lacking TLR‐9 is less capable of inducing Treg differentiation 79, which indicates that TLR‐9 functions differently in various immune cells of SLE patients. Collectively, these studies suggest that even though autoreactive antibody is a definitive feature of SLE, complex immune pathways are involved in pathogenesis directly or indirectly, and more studies must be conducted to illuminate further the role of TLR‐9 in SLE pathogenesis.

STING‐dependent pathway

An important role of IFN‐I in SLE aetiopathogenesis is proposed when SLE symptoms are observed as a side effect of IFN‐α‐treated patients with malignant diseases, such as melanoma and renal cell carcinoma 80. The majority of SLE patients have elevated IFN‐I levels in blood and IFN‐I‐stimulated genes (ISGs), a so‐called IFN signature, which correlates with stages and severity of SLE 8. IFN‐I is the driving force of pathogenesis which causes the clinical complaints of SLE patients; for instance, fever, rash and leucopenia, which are shared by patients with viral infection 81.

The STING pathway plays a vital role in IFN‐I production upon DNA stimulation. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum resident protein, and expressed broadly in numerous types of cells 82. Mammalian STING binds to DNA directly but weakly, although it is activated strongly by cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) generated directly from bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes 60, 83, 84. A key DNA interacting protein that expedites STING activity is cGAS which, in the presence of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and guanosine‐5'‐triphosphate (GTP), generates non‐canonical cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs), a second messenger that binds to and activates STING 60, 85. Once activated, STING activates TANK‐binding kinase 1(TBK1) to phosphorylate downstream transcriptional factors IRF3 and IRF7, which are responsible for IFN‐I production 60. In addition, STING interacts with signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT‐6) and induces sequentially the production of chemokines such as CCL2 and CCL20 independently of IRF3 86. STING is also thought to activate the NF‐κB pathway through regulating the NF‐κB inhibitor (IκB), although the mechanism of NF‐κB activation downstream of STING remains to be determined 64. STING‐dependent pathways orchestrate the immune response against cytosolic dsDNA, and their effects on the SLE pathogenesis are investigated extensively.

DNase II is crucial for the clearance of self‐dsDNA in lysosomes to avoid the immune response. DNase II knock‐out mice are embryonically lethal because of uncontrolled inflammation, while the deletion of cGAS in DNase II‐deficient mice rescues this lethal phenotype 87. Three prime repair exonuclease 1 (TREX1), also known as DNase III, is a DNA exonuclease involved in the clearance of cytoplasmic ssDNA and dsDNA. Lost‐function mutations of TREX1 lead to the accumulation of self‐DNA and autoimmune disease, such as Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS) and SLE in humans. TREX1‐deficient mice show dramatically reduced survival because of spontaneous inflammatory myocarditis, progressive cardiomyopathy and circulatory failure 88. Depletion of cGAS, STING, IRF3 or IFN‐I receptor in TREX1‐deficient mice rescues these mice from autoimmune disorders and mortality 87, 89, 90, suggesting that the cGAS–STING–IRF3 axis‐mediated IFN‐I production is responsible for the development of autoimmune disorders in these TREX1‐deficient mice. However, in STING‐deficient lupus mice, lymphoid hypertrophy, autoantibody production, serum cytokine levels are increased markedly, compared to their STING‐sufficient littermates 91. STING‐deficient macrophages fail to express negative regulators of TLR signalling, including cytoplasmic zinc finger protein A20 and suppressor of cytokine signalling1 (SOCS1) and 3 (SOCS3), which leads to hyper‐responsiveness to TLR ligands and abnormal production of proinflammatory cytokines 91. Collectively, these findings reveal that STING has both positive and negative regulatory roles in immune responses.

DAI has been implicated in IFN‐I production by activating the STING‐dependent pathway in response to poly(dA:dT) DNA stimulation 61. Interestingly, DAI expression is induced by activated lymphocytic‐derived apoptotic DNA treatment and the level of DAI is increased significantly in SLE patients and in lupus mouse models 92. Inhibition of DAI signalling with siRNA in lupus mouse models dampens macrophage activation and ameliorates SLE symptoms, including reduced cytokine levels in sera, anti‐dsDNA antibody production and IC deposition within the kidney 92. These findings suggest that the STING‐dependent pathway has important functions in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Inflammasome‐dependent pathway

The inflammasome is a multi‐protein oligomer formed in the myeloid cells as an important mechanism to induce the innate immune response against bacterial and viral infection. Several components of inflammasome, such as AIM2, IFI16 and NLRP3, have been proven to be sensors of self‐DNA involved in the pathogenesis of SLE 62. IC, neutrophil NETs and IFN‐I may enhance inflammasome activation in SLE 62. The activated inflammasome leads to activation of caspase‐1, and induces the processing and release of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)‐1β and IL‐18 sequentially from their latent forms. IL‐1β is important for the activation of neutrophils, macrophages, DCs and T cells, whereas IL‐18 is crucial for IFN‐γ production by natural killer (NK) cells and T cells 93. Serum levels of IL‐18 are elevated in SLE patients and are correlated with disease severity, autoantibody production and the presence of lupus nephritis. However, the role of IL‐1β in SLE is not conclusive 62.

AIM2 recognizes cytosolic self‐dsDNA and pathogen‐derived dsDNA through its HIN200 domain 94. AIM2 expression level is correlated strongly with the severity of disease in both SLE patients and the lupus mouse model. Blockage of AIM2 expression ameliorates the SLE syndrome via inhibiting macrophage activation and dampening the inflammatory response in apoptotic DNA‐induced lupus mice 95. Moreover, the expression of AIM2 is gender‐dependent and higher in macrophages of male mice or SLE patients, contrary to the gender preference of SLE 96, 97, which needs to be illuminated further.

The DNA sensor IFI16 belongs to the same ISG family as AIM2, which recognizes DNA through its HIN200 domain 98. After Kaposi sarcoma‐associated herpes virus infection, IFI16 forms an inflammasome complex 99 and recruits STING in cytoplasm, and subsequently activates the TBK1–IRF3 pathway for IFN‐I production 98. Several lines of evidence indicate that IFI16 is an important mediator of inflammation in systemic autoimmune diseases 98. IFI16 expression is induced by IFN‐I, and increased expression levels of IFI16 have been reported in leucocytes isolated from SLE patients 100.

NLRP3, the central component of inflammasome, has been demonstrated to be related to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a mouse model of multiple sclerosis 101. NLRP3‐deficient mice exhibit reduced Th1 and Th17 responses and impaired IFN‐γ and IL‐17 production 101. NETs could induce robust activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages from SLE patients and lead sequentially to the release of inflammatory cytokines, including IL‐18, that further promote NETosis 102.

Conclusions

Self‐dsDNA is restricted in the nucleus or mitochondria, whereby it is compartmentalized away from cytosolic DNA sensors in mammalian cells. Different catalogues of deoxyribonuclease, DNase I, DNase II and DNase III are located in the circulation, lysosome and endoplasmic reticulum, respectively, and are responsible for digesting the unwanted DNA efficiently. In SLE patients, because the clearance of dead cells is defective, self‐dsDNA becomes immunogenic after binding to immunogenic polypeptide and/or being modified. Ds‐DNA is one of the important triggering factors for SLE. The site and origin of dsDNA, as well as the presence of autoantibodies, are critical for the initiation and pathogenesis of SLE. Autoantibodies are produced by autoreactive B cells with the help of autoreactive T cells, although the mechanism(s) remain elusive. The IC consisting of autoantibodies and self‐dsDNA activates intracellular DNA sensors further in immune cells. A strong inflammatory response characterized by robust IFN‐I production by APCs (mainly pDCs) is induced via the activation of DNA sensor‐dependent signal pathways. The hyperproduction of IFN‐I could facilitate DC maturation in turn, and promotes the function of autoreactive T and B cells, resulting in a positive feedback loop involved in the pathogenesis of SLE, suggesting that blocking the DNA sensor‐mediated signal pathway would be a potential novel therapeutic strategy for SLE.

Disclosure

The authors declare no disclosures.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology (the National Key Research and Development Program 2016YFA0502203 to H.H., 2016YFC0906201 to Y.L., and the Recruitment Program of Global Experts to H.H.).

Contributor Information

Y. Liu, Email: yi2006liu@163.com

H. Hu, Email: hongbohu@scu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Rekvig OP. Anti‐dsDNA antibodies as a classification criterion and a diagnostic marker for systemic lupus erythematosus: critical remarks. Clin Exp Immunol 2015; 179:5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Unterholzner L. The interferon response to intracellular DNA: why so many receptors? Immunobiology 2013; 218:1312–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shrivastav M, Niewold TB. Nucleic acid sensors and type I interferon production in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol 2013; 4:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Munoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M et al The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6:280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V et al Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self‐DNA–peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Trans Med 2011; 3:73ra19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumann I, Kolowos W, Voll RE et al Impaired uptake of apoptotic cells into tingible body macrophages in germinal centers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eloranta ML, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Disease mechanisms in rheumatology – tools and pathways: plasmacytoid dendritic cells and their role in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65:853–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crow MK. Type I interferon in the pathogenesis of lupus. J Immunol 2014; 192:5459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pisetsky DS. The origin and properties of extracellular DNA: from PAMP to DAMP. Clin Immunol 2012; 144:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahajan A, Herrmann M, Munoz LE. Clearance deficiency and cell death pathways: a model for the pathogenesis of SLE. Front Immunol 2016; 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biermann M, Maueroder C, Brauner JM et al Surface code – biophysical signals for apoptotic cell clearance. Phys Biol 2013; 10:065007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu X, Molinaro C, Johnson N et al Secondary necrosis is a source of proteolytically modified forms of specific intracellular autoantigens: implications for systemic autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44:2642–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anam K, Amare M, Naik S et al Severe tissue trauma triggers the autoimmune state systemic lupus erythematosus in the MRL/++ lupus‐prone mouse. Lupus 2009; 18:318–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esposito S, Bosis S, Semino M et al Infections and systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33:1467–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM et al Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2012. Cell Death Differ 2012; 19:107–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guimaraes‐Costa AB, Nascimento MT, Wardini AB et al ETosis: a microbicidal mechanism beyond cell death. J Parasitol Res 2012; 2012:929743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Farrera C, Fadeel B. Macrophage clearance of neutrophil extracellular traps is a silent process. J Immunol 2013; 191:2647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Napirei M, Karsunky H, Zevnik B et al Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in Dnase1‐deficient mice. Nat Genet 2000; 25:177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knight JS, Subramanian V, O'Dell AA et al Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition disrupts NET formation and protects against kidney, skin and vascular disease in lupus‐prone MRL/lpr mice. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74:2199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC et al Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2011; 187:538–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kienhofer D, Hahn J, Stoof J et al Experimental lupus is aggravated in mouse strains with impaired induction of neutrophil extracellular traps. JCI Insight 2017; 2:92920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong K, Valdez Christine PA, Tan C et al Phosphatidylserine receptor Tim‐4 is essential for the maintenance of the homeostatic state of resident peritoneal macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:8712–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Botto M, Dell'Agnola C, Bygrave AE et al Homozygous C1q deficiency causes glomerulonephritis associated with multiple apoptotic bodies. Nat Genet 1998; 19:56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miyasaka K et al Autoimmune disease and impaired uptake of apoptotic cells in MFG‐E8‐deficient mice. Science 2004; 304:1147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen PL, Caricchio R, Abraham V et al Delayed apoptotic cell clearance and lupus‐like autoimmunity in mice lacking the c‐mer membrane tyrosine kinase. J Exp Med 2002; 196:135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshida H, Okabe Y, Kawane K et al Lethal anemia caused by interferon‐beta produced in mouse embryos carrying undigested DNA. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luis E, Muñoz BF, Uwe A et al Peripheral blood stem cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus show altered differentiation into macrophages. Open Autoimmun J 2010; 2:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cairns AP, Crockard AD, McConnell JR et al Reduced expression of CD44 on monocytes and neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus: relations with apoptotic neutrophils and disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis 2001; 60:950–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tas SW, Quartier P, Botto M et al Macrophages from patients with SLE and rheumatoid arthritis have defective adhesion in vitro, while only SLE macrophages have impaired uptake of apoptotic cells. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:216–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katsiari CG, Liossis SN, Sfikakis PP. The pathophysiologic role of monocytes and macrophages in systemic lupus erythematosus: a reappraisal. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 39:491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K et al Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:9813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yeh T‐M, Chang H‐C, Liang C‐C et al Deoxyribonuclease‐inhibitory antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Sci 2003; 10:544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leffler J, Martin M, Gullstrand B et al Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol 2012; 188:3522–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lood C, Blanco LP, Purmalek MM et al Neutrophil extracellular traps enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA are interferogenic and contribute to lupus‐like disease. Nat Med 2016; 22:146–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carmona‐Rivera C, Kaplan MJ. Low‐density granulocytes: a distinct class of neutrophils in systemic autoimmunity. Semin Immunopathol 2013; 35:455–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Imashuku S, Kudo N, Kaneda S. Emerging symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus triggered by knee injury. Lupus 2010; 19:776–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Azevedo PC, Murphy G, Isenberg DA. Pathology of systemic lupus erythematosus: the challenges ahead. Methods Mol Biol 2014; 1134:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gilkeson GS, Pippen AM, Pisetsky DS. Induction of cross‐reactive anti‐dsDNA antibodies in preautoimmune NZB/NZW mice by immunization with bacterial DNA. J Clin Invest 1995; 95:1398–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shirota H, Klinman DM. Recent progress concerning CpG DNA and its use as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev Vaccines 2014; 13:299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pisetsky DS. Anti‐DNA antibodies – quintessential biomarkers of SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12:102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Desai DD, Krishnan MR, Swindle JT et al Antigen‐specific induction of antibodies against native mammalian DNA in nonautoimmune mice. J Immunol 1993; 151:1614–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rekvig OP, Moens U, Sundsfjord A et al Experimental expression in mice and spontaneous expression in human SLE of polyomavirus T‐antigen. J Clin Invest 1997; 99:2045–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V et al Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self‐DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature 2007; 449:564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gehrke N, Mertens C, Zillinger T et al Oxidative damage of DNA confers resistance to cytosolic nuclease TREX1 degradation and potentiates STING‐dependent immune sensing. Immunity 2013; 39:482–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wen ZK, Xu W, Xu L et al DNA hypomethylation is crucial for apoptotic DNA to induce systemic lupus erythematosus‐like autoimmune disease in SLE‐non‐susceptible mice. Rheumatology 2007; 46:1796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Voll RE, Roth EA, Girkontaite I et al Histone‐specific Th0 and Th1 clones derived from systemic lupus erythematosus patients induce double‐stranded DNA antibody production. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40:2162–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K et al T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function‐associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest 1996; 97:2866–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Malkiel S, Jeganathan V, Wolfson S et al Checkpoints for autoreactive B Cells in the peripheral blood of lupus patients assessed by flow cytometry. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68:2210–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cappione A 3rd, Anolik JH, Pugh‐Bernard A et al Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest 2005; 115:3205–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Eloranta ML, Ronnblom L. Cause and consequences of the activated type I interferon system in SLE. J Mol Med 2016; 94:1103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Alunno A, Bartoloni E, Bistoni O et al Balance between regulatory T and Th17 cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: the old and the new. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:823085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Golding A, Rosen A, Petri M et al Interferon‐alpha regulates the dynamic balance between human activated regulatory and effector T cells: implications for antiviral and autoimmune responses. Immunology 2010; 131:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lopez P, Rodriguez‐Carrio J, Caminal‐Montero L et al A pathogenic IFNalpha, BLyS and IL‐17 axis in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Sci Rep 2016; 6:20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ittah M, Miceli‐Richard C, Eric Gottenberg J et al B cell‐activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF) is expressed under stimulation by interferon in salivary gland epithelial cells in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2006; 8:R51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bave U, Magnusson M, Eloranta ML et al Fc RIIa is expressed on natural IFN‐alpha‐producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and is required for the IFN‐alpha production induced by apoptotic cells combined with lupus IgG. J Immunol 2003; 171:3296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rönnblom L, Eloranta M‐L, Alm GV. Role of natural interferon‐α producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) in autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 2009; 36:463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Raz B EM, Rosenmann E, Eilat D. Anti‐DNA antibodies bind directly to renal antigens and induce kidney dysfunction in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Immunol 1989; 3076–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. D'Andrea DM, Coupaye‐Gerard B, Kleyman TR et al Lupus autoantibodies interact directly with distinct glomerular and vascular cell surface antigens. Kidney Int 1996; 49:1214–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Celhar T, Magalhaes R, Fairhurst AM. TLR7 and TLR9 in SLE: when sensing self goes wrong. Immunol Res 2012; 53:58–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cai X, Chiu YH, Chen ZJ. The cGAS–cGAMP–STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol Cell 2014; 54:289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK et al DAI (DLM‐1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature 2007; 448:501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. The inflammasome and lupus: another innate immune mechanism contributing. To disease pathogenesis? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014; 26:475–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Man SM, Karki R, Kanneganti TD. DNA‐sensing inflammasomes: regulation of bacterial host defense and the gut microbiota. Pathog Dis 2016; 74:ftw028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M et al The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:959–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kondo T, Kobayashi J, Saitoh T et al DNA damage sensor MRE11 recognizes cytosolic double‐stranded DNA and induces type I interferon by regulating STING trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:2969–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Smith S, Jefferies C. Role of DNA/RNA sensors and contribution to autoimmunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2014; 25:745–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jimenez‐Dalmaroni MJ, Gerswhin ME, Adamopoulos IE. The critical role of toll‐like receptors – from microbial recognition to autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern‐recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll‐like receptors. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:373–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Barber GN. Cytoplasmic DNA innate immune pathways. Immunol Rev 2011; 243:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen M, Zhang W, Xu W et al Blockade of TLR9 signaling in B cells impaired anti‐dsDNA antibody production in mice induced by activated syngenic lymphocyte‐derived DNA immunization. Mol Immunol 2011; 48:1532–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Santiago‐Raber ML, Dunand‐Sauthier I, Wu T et al Critical role of TLR7 in the acceleration of systemic lupus erythematosus in TLR9‐deficient mice. J Autoimmun 2010; 34:339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yu P, Wellmann U, Kunder S et al Toll‐like receptor 9‐independent aggravation of glomerulonephritis in a novel model of SLE. Int Immunol 2006; 18:1211–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Christensen SR, Kashgarian M, Alexopoulou L et al Toll‐like receptor 9 controls anti‐DNA autoantibody production in murine lupus. J Exp Med 2005; 202:321–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Iwamoto K et al Up‐regulated expression of Toll‐like receptors mRNAs in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol 2008; 152:482–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wong CK, Wong PT, Tam LS et al Activation profile of Toll‐like receptors of peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 159:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nickerson KM, Christensen SR, Shupe J et al TLR9 regulates TLR7‐ and MyD88‐dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J Immunol 2010; 184:1840–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fukui R, Saitoh S, Kanno A et al Unc93B1 restricts systemic lethal inflammation by orchestrating Toll‐like receptor 7 and 9 trafficking. Immunity 2011; 35:69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang J, Shao Y, Bennett TA et al The functional effects of physical interactions among Toll‐like receptors 7, 8, and 9. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:37427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Jin O, Kavikondala S, Mok MY et al Abnormalities in circulating plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12:R137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O et al Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Elkon KB, Wiedeman A. Type I IFN system in the development and manifestations of SLE. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2012; 24:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Abe T, Harashima A, Xia T et al STING recognition of cytoplasmic DNA instigates cellular defense. Mol Cell 2013; 50:5–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo‐Troha K et al STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di‐GMP. Nature 2011; 478:515–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c‐di‐AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 2010; 328:1703–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sun L, Wu J, Du F et al Cyclic GMP‐AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013; 339:786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Burdette DL, Vance RE. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gao D, Li T, Li XD et al Activation of cyclic GMP‐AMP synthase by self‐DNA causes autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:E5699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Yang YG, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Trex1 exonuclease degrades ssDNA to prevent chronic checkpoint activation and autoimmune disease. Cell 2007; 131:873–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T et al Trex1 prevents cell‐intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell 2008; 134:587–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ahn J, Ruiz P, Barber GN. Intrinsic self‐DNA triggers inflammatory disease dependent on STING. J Immunol 2014; 193:4634–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sharmaa S, Campbellb AM, Chana J et al Suppression of systemic autoimmunity by the innate immune adaptor STING. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:E710–E17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang W, Zhou Q, Xu W et al DNA‐dependent activator of interferon‐regulatory factors (DAI) promotes lupus nephritis by activating the calcium pathway. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:13534–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yang CA, Chiang BL. Inflammasomes and human autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2015; 61:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Fernandes‐Alnemri T, Yu JW, Juliana C et al The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis . Nat Immunol 2010; 11:385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang W, Cai Y, Xu W et al AIM2 facilitates the apoptotic DNA‐induced systemic lupus erythematosus via arbitrating macrophage functional maturation. J Clin Immunol 2013; 33:925–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Panchanathan R, Duan X, Arumugam M et al Cell type and gender‐dependent differential regulation of the p202 and Aim2 proteins: implications for the regulation of innate immune responses in SLE. Mol Immunol 2011; 49:273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Yang CA, Huang ST, Chiang BL. Sex‐dependent differential activation of NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes in SLE macrophages. Rheumatology 2015; 54:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Unterholzner L, Keating SE, Baran M et al IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kerur N, Veettil MV, Sharma‐Walia N et al IFI16 acts as a nuclear pathogen sensor to induce the inflammasome in response to Kaposi sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus infection. Cell Host Microbe 2011; 9:363–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kimkong I, Avihingsanon Y, Hirankarn N. Expression profile of HIN200 in leukocytes and renal biopsy of SLE patients by real‐time RT–PCR. Lupus 2009; 18:1066–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gris D, Ye Z, Iocca HA et al NLRP3 plays a critical role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by mediating Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol 2010; 185:974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Kahlenberg JM, Carmona‐Rivera C, Smith CK et al Neutrophil extracellular trap‐associated protein activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is enhanced in lupus macrophages. J Immunol 2013; 190:1217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]