Abstract

Objectives:

Sickness presenteeism (SP) is postulated as workers' response to their general state of health; hence, SP is expected to affect workers' future health. In the present study, we examined the reciprocal relationship between SP and health in response to job stressors, with specific reference to psychological distress (PD) as workers' state of health.

Methods:

We conducted mediation analysis, using data from a three-wave cohort occupational survey conducted at 1-year intervals in Japan; it involved 1,853 employees (1,661 men and 192 women) of a manufacturing firm. We measured SP and PD, using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire and Kessler 6 score, respectively. For job stressors, we considered job demands and control, effort and reward, and procedural and interactional justice.

Results:

PD mediated 11.5%-36.2% of the impact of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice on SP, whereas SP mediated their impact on PD, albeit to a much lesser extent in the range of 3.4%-11.3%. Unlike in the cases of these job stressors related to job resources, neither SP nor PD mediated the impact of job demands or effort.

Conclusions:

Our results confirmed the reciprocal relationship between SP and PD in response to selected types of job stressors, emphasizing the need for more in-depth analysis of the dynamics of these associations.

Keywords: Job stressor, Psychological distress, Sickness presenteeism

Introduction

An increasing number of studies in occupational health have been focusing on sickness presenteeism (SP)1,2). SP generally has two definitions, which renders discussions regarding its reference to health somewhat confusing3). The first definition refers to attending work despite feeling ill2,4,5). The second definition centers on reduced productivity at work owing to health problems3,6). These two definitions suggest that SP and workers' health may be affected by each other, as the former refers to the adverse impact of SP on workers' health, whereas the later focuses on the causality from health problems to SP.

Actually, the empirical model of SP consists of two parts7): first, SP is postulated as workers' response to their general state of health, and second, SP is expected to affect workers' future health. The first part explicitly or implicitly assumes the causation from health to SP, whereas the second assumes the reverse causation. Most of the previous studies have focused on either part of the SP model, but not both. Specifically, studies focusing on the first part have found that SP was determined by psychosocial characteristics of work and individual factors7-10). Studies have also emphasized that mental health problems are a major cause of SP11,12). Meanwhile, studies examining the second part have shown the predictive validity of SP for health outcomes13), including sickness absence4), self-rated health14), burnout15), depression16,17), and other aspects of mental well-being. These two parts of the SP model indicate a reciprocal relationship between SP and health, both of which are likely to be affected by work characteristics as well as individual factors.

Hence, we can generally hypothesize that health problems may mediate the impact of work characteristics on SP, whereas SP may mediate the impact of work characteristics on health. We examined our hypothesis of this mutual mediation system, taking advantage of three-wave cohort data, which allowed us to alleviate potential simultaneity biases. Although the mediating role of health has been observed in previous works18-20), studies addressing the role of SP have been sparse, except for one published report15); this lack of investigation has left this reciprocal relationship only partially examined.

For the purpose of operationalization, we first measured SP, using the validated Japanese version of the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ)21). The HPQ asks respondents to assess their job performance, and therefore, is linked to the second definition of SP, which centers on reduced productivity at work. It should be noted that the HPQ-based SP measures may reflect reduced productivity owing to reasons other than health problems as well. Meanwhile, the HPQ-based SP measures have been shown to be closely associated with health indicators as well as objective job performance22-24). Hence, in the present study we focused on how the HPQ-based SP measures were actually affected by health problems while investigating their role as a mediator between job stressors and health. Second, we focused on psychological distress (PD) measured by scores on the Kessler 6 (K6) scale25) as an indicator of workers' mental health status. For this aspect, we considered previous evidence that presenteeism is sensitive to mental health problems11,12) and that presenteeism raises the risk of those problems15-17). Third, we considered six types of job stressors in terms of job demands and control, effort and reward, and procedural and interactional justice as psychosocial characteristics of work that could raise SP as well as PD, as observed in previous studies26,27). It is interesting to examine how the association between SP and PD may differ in response to different types of job stressors.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We used panel data from an occupational cohort study on social class and health in Japan (Japanese Study of Health, Occupation, and Psychosocial Factors Related Equity; J-HOPE). The first wave was conducted from October 2010 to December 2011, and the following three waves were conducted approximately one year later. The entire sample of J-HOPE consisted of employees from 13 firms, spanning 12 industries. SP was queried only among employees of one manufacturing firm in the third and fourth waves.

In the present study, we focused on those participants and used their data from the second, third, and fourth survey waves of J-HOPE, with approximately one-year intervals. Specifically, we observed job stressors in the second wave and SP and PD in the third and fourth waves. Hereafter, we refer to the second, third, and fourth survey waves as "baseline," "1-year follow-up," and "2-year follow-up," respectively. Excluding those participants with missing key variables, we finally analyzed 5,589 observations for 1,853 participants (1,661 men and 192 women), representing 77.3% of the total 2,397 participants. The attrition rate was relatively low, 8.4% from baseline to 1-year follow-up and 1.0% from 1-year to 2-year follow-up.

The Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine/Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tokyo, Kitasato University School of Medicine/Hospital, and the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan, reviewed and approved the study aims and procedures (No. 2772, B12-103 and 10-004, respectively). The analyses were conducted using the J-HOPE dataset as of 22 August 2014.

Measures

Sickness presenteeism

We used the validated Japanese version of the WHO-HPQ short form24), following a previous study17). The HPQ comprises two questions: "On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst job performance anyone could have at your job and 10 is the performance of a top worker, how would you rate the usual performance of most workers in a job similar to yours?" and "Using the same 0-10 scale, how would you rate your overall job performance on the days you worked during the past four weeks?" We used responses to the second question to obtain the degree of "absolute" SP, rather than "relative" SP, which is derived from the comparison with others' job performance based on the responses to both questions. The validity of this HPQ-based SP measure has been demonstrated in terms of its associations with job performance and health22-24), and its reliability has been confirmed by comparing the results at two points in time22). We constructed a continuous variable of SP (range: 0-10) by reversing the answered score, making the higher score meaning a higher level of SP.

Psychological distress

We determined K6 scores, to measure PD25,28). The reliability and validity of the K6 scale have been demonstrated in a Japanese population29,30). From the survey, we first obtained the respondents' assessments of their psychological health, who were queried using a six-item question: "During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel a) nervous, b) hopeless, c) restless or fidgety, d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, e) that everything was an effort, and f) worthless?" Responses were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = none of the time; 4 = all of the time). Cronbach's α in the current sample was 0.90. Further, we calculated the sum of the reported scores (range: 0-24) and defined this as the K6 score with a higher score meaning a higher level of PD.

Job stressors

We considered six types of job stressors: job demands and control [based on the Job Demands-Control (JD-C) model31)], effort and reward [based on the Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) model32)], and procedural and interactional justice [based on the organizational justice model33)]. To assess job demands and control, we utilized those items investigating job demands and control from the Japanese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ)31,34). The JCQ includes scales related to job demands (five items) and job control (nine items), rated on a four-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). The internal consistency, reliability, and validity of the Japanese version of the JCQ have shown to be acceptable34). Cronbach's αs in the current sample were 0.69 and 0.76 for job demands and control, respectively. We summed the responses to these items into single indices of job demands (range: 12-48) and control (range: 24-96). To assess effort and reward, we used the data collected from a simplified Japanese version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERIQ)32,35). The ERIQ included subscales for effort (three items) and reward (seven items), rated on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). The Japanese version of the ERIQ has been shown to have acceptable internal consistency, reliability, and validity scores35). Cronbach's αs in the current sample were 0.79 and 0.78 for effort and reward, respectively. We summed the responses into single indices for effort (range: 3-12) and reward (range: 7-28). We also measured procedural and interactional aspects of organizational justice by the Japanese version of the Organizational Justice Questionnaire (OJQ)33,36). The reliability and validity of the Japanese version have been largely confirmed36). The OJQ comprises a seven-item scale, measuring procedural justice, and a six-item scale, measuring interactional justice, both rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach's αs in the current sample were 0.90 and 0.95 for procedural and interactional justice, respectively. For each justice type, we summed all item scores and divided that number by the number of items in that particular category, yielding a variable with a score ranging from 1 to 5. We used all of these variables as continuous ones.

Covariates

For socioeconomic and sociodemographic covariates, we used sex, age, educational attainment (high school or below, junior college, college, and graduate school), job classification (managerial, non-manual, manual, and other), type of service (only day, shift including night service, and shift excluding night service), hours worked per week (< 30, 31-40, 41-50, 51-60, and ≥61 h), and income (adjusted for household size by dividing the root of the number of household members). We also controlled for three types of health behaviors: smoking (not smoking, quit smoking, and smoking), alcohol consumption (never, sometimes, and almost every day), and physical activity (never, light exercise once or more a week, moderate or more exercise once or twice a week, and moderate or more exercise three times or more a week).

Statistical analyses

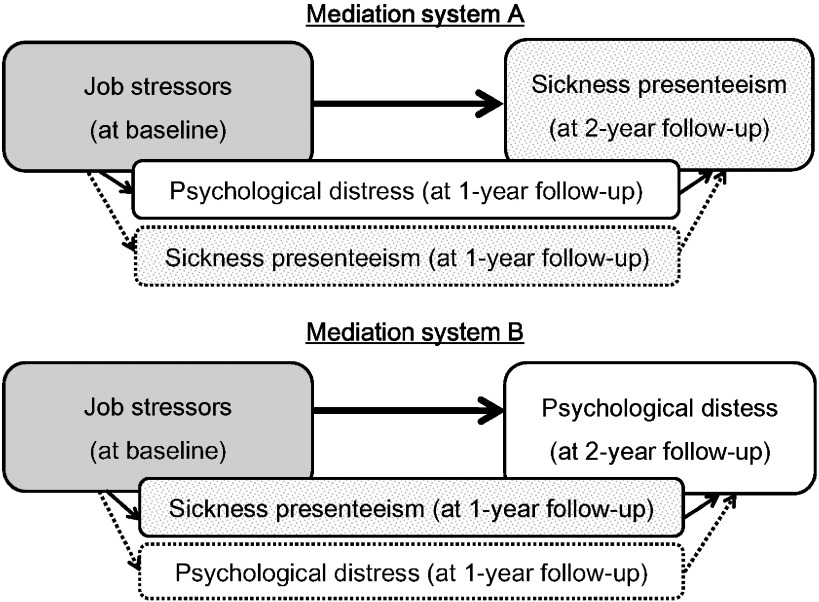

To examine the validity of the hypothesis that PD may mediate the impact of job stressors on SP, while SP may mediate the impact of job stressors on PD, we considered two mediation systems (Fig. 1). Mediation system A assumed that PD at 1-year follow-up would mediate the impact of job stressors at baseline on SP at 2-year follow-up. Here we controlled for the mediating effect of SP at 1-year follow-up, considering that higher SP (i.e., lower job performance), possibly caused by job stressors, may make workers frustrated and/or distressed, and hence, raise their PD, and at the same time, it may add to future SP as well, both confounding the association between PD and SP. Meanwhile, Mediation system B assumed that SP at 1-year follow-up would mediate the impact of job stressors at baseline on PD at 2-year follow-up. In this system, we controlled for the mediating effect of PD at 1-year follow-up, which may confound the association between SP and PD. To examine these mediation systems, we applied the conventional three-step framework of mediation analysis37,38). In the case of Mediation system A, we estimated four linear regression models: Models 1-1 and 1-2 to explain PD and SP, respectively, at 1-year follow-up by each job stressor at baseline; Model 2 to explain SP at 2-year follow-up by each job stressor; and Model 3 to explain SP at 2-year follow-up by each job stressor and by PD and SP at 1-year follow-up. A set of covariates were controlled for in all the models. After estimating the regression models, we computed the proportion of impact of each job stressor at baseline on SP mediated by PD and SP at 2-year follow-up, along with its 95% confidence interval (CI) obtained by bootstrap estimation with 2,000 replications. For Mediation system B, we repeated these calculations by replacing SP and PD with each other.

Fig. 1.

Mutual mediation system across job stressors, sickness presenteeism, and psychological distress

Results

Key features of the study participants at baseline are summarized in Table 1. Most employees provided only day service, and about a half of them were non-manual workers and worked for 41-50 hours per week. Pairwise correlation coefficients across key variables, calculated using their pooled cross-sectional data at 1-year and 2-year follow-ups and unadjusted for covariates, are presented in Table 2. This table presents an unadjusted picture of the associations across key variables. SP was positively associated with PD and negatively associated with job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice. Meanwhile, SP was not significantly associated with effort, and its negative association with job demands was more limited and less significant compared to other job characteristics.

Table 1.

Key features of participants at baseline

| Total | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| M | 44.2 | 44.3 | 42.6 | |

| SD | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.0 | |

| Educational attainment (%) | ||||

| High school or below | 31.4 | 31.4 | 31.3 | |

| Junior college | 9.1 | 5.8 | 37.0 | |

| College | 42.6 | 44.4 | 26.6 | |

| Graduate school | 17.0 | 18.4 | 5.2 | |

| Job classification (%) | ||||

| Managerial workers | 25.6 | 28.4 | 1.6 | |

| Non-manual workers | 47.1 | 41.7 | 93.8 | |

| Manual workers | 18.1 | 20.0 | 1.6 | |

| Other workers | 9.2 | 9.9 | 3.1 | |

| Type of service (%) | ||||

| Only day service | 94.9 | 94.3 | 99.5 | |

| Shift service (including night service) | 4.5 | 4.9 | 0.5 | |

| Shift service (excluding night service) | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

| Hours worked per week (%) | ||||

| Less than 30 hours | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.6 | |

| 31-40 hours | 17.6 | 15.5 | 35.4 | |

| 41-50 hours | 49.8 | 49.5 | 52.1 | |

| 51-60 hours | 22.3 | 23.8 | 9.4 | |

| 61 hours or more | 7.5 | 8.3 | 0.5 | |

| Smoking (%) | ||||

| Not smoking | 60.2 | 56.7 | 90.6 | |

| Quitted smoking | 11.7 | 12.5 | 4.2 | |

| Smoking | 28.1 | 30.8 | 5.2 | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| Never | 28.8 | 26.6 | 47.9 | |

| Sometimes | 36.2 | 36.1 | 37.0 | |

| Almost every day | 35.0 | 37.3 | 15.1 | |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Never | 54.0 | 53.4 | 59.4 | |

| Light exercise once or more a week | 26.8 | 27.2 | 22.9 | |

| Moderate or more exercise once or twice a week | 14.8 | 14.9 | 13.5 | |

| Moderate or more exercise three times or more a week | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.2 | |

| Income (thousand yen, household-size-adjusted) | ||||

| M | 4,659 | 4,616 | 5,030 | |

| SD | 1,948 | 1,931 | 2,056 | |

| n | 1,853 | 1,661 | 192 | |

Table 2.

Pairwise correlation across key variablesa (N=4,072)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

a Based on data pooled at 1-year and 2-year follow-ups, unadjusted for covariates. *** p<.001, * p<.05 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. | Sickness presenteeism (SP) | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 2. | Psychological distress (PD) | 0.341 | *** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3. | Job demands | –0.040 | * | 0.238 | *** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. | Job control | –0.264 | *** | –0.161 | *** | 0.225 | *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. | Effort | –0.021 | 0.246 | *** | 0.641 | *** | 0.166 | *** | 1 | |||||||

| 6. | Reward | –0.237 | *** | –0.383 | *** | –0.064 | *** | 0.377 | *** | –0.066 | *** | 1 | ||||

| 7. | Procedural justice | –0.220 | *** | –0.294 | *** | –0.081 | *** | 0.326 | *** | –0.100 | *** | 0.507 | *** | 1 | ||

| 8. | Interactional justice | –0.193 | *** | –0.285 | *** | –0.027 | 0.360 | *** | –0.057 | *** | 0.548 | *** | 0.666 | *** | 1 | |

The estimation results of Mediation system A are presented in Table 3. The estimated coefficients and β were standardized to help comparisons across job stressors. The results of Model 1-1 confirmed the adverse impact of all types of job stressors at baseline on PD at 1-year follow-up, while Model 1-2 showed that SP at 1-year follow-up had no association with effort and a relatively limited association with job demands. The findings from Model 2 presented results similar to those of Model 1-2, because Model 2 replaced the dependent variable, SP, with its value one year later. After adding PD and SP at 1-year follow-up as explanatory variables in Model 3, we found that the association between each job stressor at baseline and SP at 1-year follow-up was non-significant (except for job demands). We also observed that SP at 2-year follow-up was positively associated with both PD and SP at 1-year follow-up for all types of job stressors. Combined with the results in Models 1-1, 1-2, and 2, these findings suggest that PD at 1-year follow-up mediated the impacts of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice at baseline on SP at 2-year follow-up, despite controlling for the mediating effect of SP at 1-year follow-up.

Table 3.

Estimated associations across job stressors, sickness presenteeism (SP), and psychological distress (SD) in Mediation system Aa

| Model | Model 1-1 | Model 1-2 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, job classification, types of service, hours worked per week, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. N=1,853. *** p<.001, ** p<.01, * p<.05. | ||||||||||||

| Dependent variable | PD (1-year follow-up) | SP (1-year follow-up) | SP (2-year follow-up) | SP (2-year follow-up) | ||||||||

| Independent variable | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | ||||

| Job demands | 0.173 | *** | (0.024) | –0.042 | * | (0.024) | –0.043 | (0.024) | –0.049 | * | (0.022) | |

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.125 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.386 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| Job control | –0.141 | *** | (0.026) | –0.209 | *** | (0.026) | –0.138 | *** | (0.026) | –0.042 | (0.024) | |

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.113 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.384 | *** | (0.023) | |||||||||

| Effort | 0.173 | *** | (0.023) | –0.028 | (0.023) | –0.030 | (0.024) | –0.041 | (0.022) | |||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.123 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.387 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| Reward | –0.354 | *** | (0.024) | –0.225 | *** | (0.024) | –0.116 | *** | (0.025) | 0.014 | (0.024) | |

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.119 | *** | (0.023) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.392 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| Procedural justice | –0.233 | *** | (0.023) | –0.146 | *** | (0.023) | –0.110 | *** | (0.023) | –0.028 | (0.022) | |

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.110 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.388 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| Interactional justice | –0.221 | *** | (0.023) | –0.163 | *** | (0.023) | –0.094 | *** | (0.024) | –0.005 | (0.022) | |

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.114 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.390 | *** | (0.022) | |||||||||

Table 4 summarizes the estimation results of Mediation system B, which replaced SP and PD with each other. The results of Models 1-1 and 1-2 were equivalent to those of Models 1-2 and 1-1, respectively, in Table 3. Notably, Model 1-1 suggested that SP did not mediate the impact of effort and had a limited mediating effect, if any, for job demands. Model 2 provided results similar to those of Model 1-2, as shown in Table 3. After adding SP and PD at 1-year follow-up as explanatory variables in Model 3, the associations between each job stressor and PD at 2-year follow-up were attenuated or non-significant, whereas PD at 2-year follow-up was positively associated with both SP and PD at 1-year follow-up. Overall, we obtained results symmetric to those of Mediation system A: SP at 1-year follow-up mediated the impacts of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice at baseline on SP at 2-year follow-up, despite controlling for the mediating effect of PD at 1-year follow-up.

Table 4.

Estimated associations across job stressors, sickness presenteeism (SP), and psychological distress (SD) in Mediation system Ba

| Model 1-1 | Model 1-2 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, job classification, types of service, hours worked per week, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. N=1,853. *** p<.001, ** p<.01, * p<.05. | ||||||||||||

| Dependent variable | SP (1-year follow-up) | PD (1-year follow-up) | PD (2-year follow-up) | PD (2-year follow-up) | ||||||||

| Independent variable | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | β | (SE) | ||||

| Job demands | –0.042 | * | (0.024) | 0.173 | *** | (0.024) | 0.150 | *** | (0.024) | 0.053 | ** | (0.020) |

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.057 | ** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.572 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Job control | –0.209 | *** | (0.026) | –0.141 | *** | (0.026) | –0.095 | *** | (0.026) | –0.002 | (0.021) | |

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.051 | * | (0.020) | |||||||||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.582 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Effort | –0.028 | (0.023) | 0.173 | *** | (0.023) | 0.118 | *** | (0.024) | 0.019 | (0.019) | ||

| Sickness absenteeism | 0.053 | ** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Psychological distress | 0.579 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Reward | –0.225 | *** | (0.024) | –0.354 | *** | (0.024) | –0.271 | *** | (0.024) | –0.060 | ** | (0.021) |

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.045 | * | (0.020) | |||||||||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.566 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Procedural justice | –0.146 | *** | (0.023) | –0.233 | *** | (0.023) | –0.200 | *** | (0.023) | –0.060 | ** | (0.019) |

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.047 | * | (0.020) | |||||||||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.570 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

| Interactional justice | –0.163 | *** | (0.023) | –0.221 | *** | (0.023) | –0.164 | *** | (0.024) | –0.028 | (0.020) | |

| SP (1-year follow-up) | 0.049 | * | (0.020) | |||||||||

| PD (1-year follow-up) | 0.578 | *** | (0.020) | |||||||||

Finally, Table 5 provides the proportion (%) of the impact of each job stressor mediated by PD and SP, in addition to their bootstrap-estimated 95% CI with 2,000 replications. The results for job demands or effort are not reported, because Table 3 indicates that PD did not mediate their impact on SP and Table 4 indicates that SP did not mediate their impacts on PD. The upper half of Table 5 confirms that PD at 1-year follow-up mediated the impacts of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice at baseline on SP at 2-year follow-up, despite controlling for the mediating effects of SP at 1-year follow-up. For these job stressors, the proportion of the impact mediated by PD was in the range of 11.5% (job control) to 36.2% (reward). The proportion of the impact mediated by SP at 1-year follow-up was higher in the range of 58.0% (job control) to 75.9% (reward). The lower half of the table demonstrates that SP mediated the impacts of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice on PD. For these job stressors, the proportion of the impact mediated by SP was between 3.4% (reward) and 11.3% (job control), much lower than the magnitudes of the mediating effects of PD (except for job control). The proportion of the impact mediated by PD at 1-year follow-up was higher in the range of 66.6% (procedural justice) to 86.8% (reward).

Table 5.

Comparison of mediating effects: psychological distress (PD) vs. sickness presenteeism (SP) a

| Mediation system A | Impact on SP (at 2-year follow-up) mediated by: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD (at 1-year follow-up) | SP (at 1-year follow-up) | ||||

| Impact of (at baseline): | Percent | (95% CI) b | Percent | (95% CI) | |

|

a Adjusted for sex, age, educational attainment, job classification, types of service, hours worked per week, income, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity. N=1,853. b Bootstrap-estimated 95% confidence interval with 2,000 replications. | |||||

| Job demands | – | – | – | – | |

| Job control | 11.5 | (6.3, 18.9) | 58.0 | (42.0, 74.6) | |

| Effort | – | – | – | – | |

| Reward | 36.2 | (21.2, 52.6) | 75.9 | (57.5, 97.3) | |

| Procedural justice | 31.1 | (17.5, 47.0) | 68.9 | (44.4, 94.8) | |

| Interactional justice | 28.5 | (16.6, 43.1) | 71.5 | (48.1, 95.4) | |

| Mediation system B | Impact on PD (at 2-year follow-up) mediated by: | ||||

| SP (at 1-year follow-up) | PD (at 1-year follow-up) | ||||

| Impact of (at baseline): | Percent | (95% CI) | Percent | (95% CI) | |

| Job demands | – | – | – | – | |

| Job control | 11.3 | (2.0, 23.8) | 86.8 | (52.4, 120.5) | |

| Effort | – | – | – | – | |

| Reward | 3.7 | (0.0, 7.7) | 74.0 | (62.0, 85.9) | |

| Procedural justice | 3.4 | (0.3, 7.6) | 66.6 | (52.3, 82.2) | |

| Interactional justice | 4.8 | (0.4, 10.0) | 77.9 | (59.3, 97.0) | |

Discussion

Following preceding studies that have separately demonstrated the impact of mental health problems on SP11,12) and that of SP on mental health problems4,13-17), we examined the hypothesis that SP and PD are mutually associated with each other in response to job stressors, using occupational data of a three-wave cohort study; the results were largely supportive of this hypothesis. We observed that PD mediated the impacts of selected job stressors on SP, whereas SP mediated their impacts on PD, albeit to a much lesser extent. The novelty of the present study is that it confirms the mutual mediating effects of both SP and PD on the impact of job stressors on each other, using a common dataset, unlike preceding studies that have only investigated the mediating effect of SP and PD separately15,18-20).

Two additional findings of the present study provide new insight into the relevance of SP to PD. First, the magnitude of the mediating effect was much larger for PD than for SP (except for job control). One may speculate that this difference is attributable to the definition of SP. In the present study, we used the definition of (absolute) SP measured by the WHO-HPQ, which queries respondents about their overall job performance. As noted in the introduction section, SP generally has two definitions: attending work despite feeling ill, and reduced productivity at work owing to health problems. The WHO-HPQ focuses on the second definition of SP, which is more likely to be affected by the mediating effect of PD as compared with the first definition, which centers on obligation and/or responsibilities in the workplace that urge employees to work regardless of the state of their health. Meanwhile, results suggested that the mediating effects of SP were relatively limited. This is probably because the second definition of SP focuses on the employee's subjective assessment of job performance, limiting the scope of the mediating role played by SP on the impact of job stressors on PD. We cannot rule out the possibility of obtaining different results when using different definitions.

Another notable finding is that the mediating effects of PD and SP differed according to the type of job stressor. Both PD and SP mediated the impacts of job control, reward, and procedural and interactional justice on each other. These types of job stressors present a shortage of job resources, which are expected to help employees achieve their work goals, reduce job demands and related physiological and psychological costs, and/or stimulate personal development39). In contrast, neither PD nor SP mediated the impact of job demands or effort on each other. Again, these results seem to be associated with the definition of SP. The WHO-HPQ definition of SP refers to perceived job performance, which may deteriorate if job resources are considered so low that they may hamper job performance. Hence, low job resources may lead to high SP; in the present study, this in turn raised PD, meaning that SP mediated the impact of low job resources on PD. Conversely, high job demands, which are usually accompanied by high effort, are likely to force employees to enhance their job performance, and hence, reduce, rather than enhance SP, resulting in a converse mediating effect of SP on the impact of high job demands on PD. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of observing the opposite result if we use the definition of SP that focuses on the other aspect of SP (attending work despite feeling sick), as suggested by the previous studies that have examined the impact of job demands on SP9,14).

We acknowledge that the current study has several limitations. First, the HPQ-based SP measures used in this study likely reflected reduced productivity because of reasons other than health problems as well, probably resulting in the underestimated sensitivity of SP to PD. Second, we exclusively focused on the association of SP with job stressors and PD; hence, we largely neglected other factors that could potentially affect SP. Third, our statistical analysis was based on a highly male-dominated sample of employees working for a manufacturing firm; this necessitates exercising caution with regard to any generalization, even in a Japanese population. Fourth, we did not control for potential biases caused by missing variables, attrition, or time-invariant individual attributes, all of which are likely to have confounded the observed associations across key variables. Lastly, we did not fully specify the causation across job stressors, SP, and PD, even though we used a three-wave cohort dataset.

Despite these limitations, our results confirmed the reciprocal relationship between SP and PD in response to selected types of job stressors, underscoring the need for an in-depth analysis of the dynamics of their associations. We can expand this type of analysis to examine the relevance of SP to another aspect or general status of workers' health. In addition, the different results across types of job stressors suggest that the definition of SP should be elaborated further.

Acknowledgments: This study was supported by the following: (1) JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Research in a Proposed Research Area) 2009-2013, Grant Number 4102-21119001; (2) JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research 2010-2014, Grant Number 22000001; and (3) JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number 26253042.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1). Aronsson G, Gustafsson K, Dallner M. Sick but yet at work-An empirical study of sickness presenteeism -. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54: 502-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Aronsson G, Gustafsson K. Sickness presenteeism: prevalence, attendance pressure factors, and an outline of a model for research. J Occup Env Med 2005; 47: 958-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Johns G. Presenteeism in the workplace: a review and research agenda. J Organ Behav 2010; 31: 519-542. [Google Scholar]

- 4). Hansen CD, Andersen JH. Sick at work-a risk factor for long-term sickness absence at a later date? J of Epidemiol Community Health 2009; 63: 397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Hansson M, Boström C, Harms-Ringdahl K. Sickness absence and sickness attendance-what people with neck or back pain think. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62: 2183-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Schultz AB, Edington DW. Employee health and presenteeism: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2007; 17: 547-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Claes R. Employee correlates of sickness presence: a study across four European countries. Work Stress 2011; 25: 224-242. [Google Scholar]

- 8). Biron C, Brun JP, Ivers H, et al. . At work but ill: psychosocial work environment and well-being determinants of presenteeism propensity. J Public Ment Health 2006; 5: 26-37. [Google Scholar]

- 9). Janssens H, Clays E, de Clercq B, et al. . Association between psychosocial characteristics of work and presenteeism: a cross-sectional study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2016; 29: 331-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Karlsson ML, Bjoerklund C, Jensen I. The effects of psychosocial work factors on production loss, and the mediating effect of employee health. J Occup Env Med 2010; 52: 310-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Dewa CS, McDaid D, Ettner SL. An international perspective on worker mental health problems: who bears the burden and how are costs addressed? Can J Psychiatry 2007; 52: 346-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Sanderson K, Tilse E, Nicholson J, et al. . Which presenteeism measures are more sensitive to depression and anxiety? J Affect Disord 2007; 101: 65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Skagen K, Collins AM. The consequences of sickness presenteeism on health and wellbeing over time: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2016; 161: 169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Gustafsson K, Marklund S. Consequences of sickness presence and sickness absence on health and work ability: a Swedish prospective cohort study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2011; 24: 153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Demerouti E, Le Blanc PM, Bakker AB, et al. . Present but sick: a three-wave study on job demands, presenteeism and burnout. Career Dev Int 2009; 14: 50-68. [Google Scholar]

- 16). Conway PM, Hogh A, Rugulies R, et al. . Is sickness presenteeism a risk factor for depression? A Danish 2-year follow-up study. J Occup Env Med 2014; 56: 595-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Suzuki T, Miyaki K, Song Y, et al. . Relationship between sickness presenteeism (WHO-HPQ) with depression and sickness absence due to mental disease in a cohort of Japanese workers. J Affect Disord 2015; 180: 14-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). McGregor A, Iverson D, Caputi P, et al. . Relationships between work environment factors and presenteeism mediated by employees' health: a preliminary study. J Occup Env Med 2014; 56: 319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Wang J, Schmitz N, Smailes E, et al. . Workplace characteristics, depression, and health-related presenteeism in a general population sample. J Occup Env Med 2010; 52: 836-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Yang T, Zhu M, Xie X. The determinants of presenteeism: a comprehensive investigation of stress-related factors at work, health, and individual factors among the aging workforce. J Occup Health 2016; 58: 25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Kessler R, Petukhova M, Mcinnes K. World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). Japanese version of the HPQ Short Form (Absenteeism and Presenteeism Questions and Scoring Rules). [Online]. 2007[cited 2017 Aug. 2]; Available from: URL: http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/hpq/info.php.

- 22). Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, et al. . Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect work place costs of illness. J Occup Env Med 2004; 46: S23-S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, et al. . The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Env Med 2003; 45: 156-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Scuffham PA, Vecchio N, Whiteford HA. Exploring the validity of HPQ-based presenteeism measures to estimate productivity losses in the health and education sectors. Med Decis Making 2014; 34: 127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. . Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific depression. Psychol Med 2002; 32: 959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Gosselin E, Lemyre L, Corneil W. Presenteeism and absenteeism: differentiated understanding of related phenomena. J Occup Health Psychol 2013; 18: 75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Janssens H, Clays E, De Clercq B, et al. . The relation between presenteeism and different types of future sickness absence. J Occup Health 2013; 55: 132-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. . Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2010; 19: 4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. . The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods in Psychiatr Res 2008; 17: 152-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Sakurai K, Nishi A, Kondo K, et al. . Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011; 65: 434-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Karasek R. Job Content Questionnaire and User's Guide. Lowell: University of Massachusetts at Lowell; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 32). Siegrist J, Wege N, Pühlhofer F, et al. . A short generic measure of work stress in the era of globalization: Effort-reward imbalance. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2009; 82: 1005-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Elovainio M, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J. Organizational justice: evidence of a new psychosocial predictor of health. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 105-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Kawakami N, Kobayashi F, Araki S, et al. . Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job demands-control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of Job Content Questionnaire. Int J Behav Med 1995; 2: 358-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Tsutsumi A, Ishitake T, Peter R, et al. . The Japanese version of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Questionnaire: a study in dental technicians. Work Stress 2001; 15: 86-96. [Google Scholar]

- 36). Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsutsumi A, et al. . Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Organizational Justice Questionnaire. J Occup Health 2009; 51: 74-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51: 1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Mackinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev 1993; 17: 144-158. [Google Scholar]

- 39). Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J Manage Psychol 2007; 22: 309-328. [Google Scholar]