Abstract

Age-related decrements in cognitive ability have been proposed to stem from deteriorating function of the hippocampus. Many birds are long lived, especially for their relatively small body mass and elevated metabolism, making them a unique model of resilience to aging. Nevertheless, little is known about avian age-related changes in cognition and hippocampal physiology. We studied spatial cognition and hippocampal expression of the age-related gene, Apolipoprotein D (ApoD), and the immediate early gene Egr-1 in zebra finches at various developmental time-points. In a first experiment, middle-aged adult males outperformed middle-aged females in learning correct food locations in a 4-arm maze, but all birds remembered the task equally well after a 5- or 10-day delay. In a second experiment comparing young and old birds, aged birds showed minimal evidence for deterioration in spatial cognition or motivation relative to young birds, except that aged females showed less rapid gains in accuracy during spatial learning than young females. These findings indicate that sex differences in hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and decline with age are phylogenetically conserved. With respect to hippocampal gene expression, adult females expressed Egr-1 at significantly greater levels than males after memory retrieval, perhaps reflecting a neurobiological compensation. Contrary to mammals, ApoD expression was elevated in young zebra finches compared to aged birds. This may explain the near absence of decrements in spatial memory due to age, possibly indicating an alternative mechanism of managing oxidative stress in aged birds.

Keywords: Songbirds, Hippocampus, Apolipoprotein D, Egr-1, ZENK, cognition

1. Introduction

Aging is a major risk factor for neurodegenerative disease, with cognitive decline especially damaging to quality of life in the elderly. Consequently, age-related memory impairment and memory loss as a result of neurodegenerative disease has emerged as an active area of research (Burns & Iliffe, 2009; Larson, Yaffe, & Langa, 2013). On top of distinct age-related neuropathologies, normal aging is associated with structural, biochemical, and functional alterations of the central nervous system (Burke & Barnes, 2006; Lister & Barnes, 2009). In particular, the hippocampus, a brain region that plays a critical role in learning and memory, is vulnerable to decline. Morphologically, the aging hippocampus (HP) shows a reduction in volume (Driscoll et al., 2003), loss of dendritic spines (Scheibel, 1979), and a decrease in adult neural stem cells and neurogenesis (van Praag, Shubert, Zhao, & Gage, 2005). Furthermore, aged humans and animals display impaired performance in HP-dependent memory tasks, such as those involving spatial navigation (Gazova et al., 2012; Winocur & Moscovitch, 1990). Specifically, the mode of spatial learning that utilizes reference or “place” strategies is diminished in aged animals (Barnes, 1987; Barnes, Nadel, & Honig, 1980; Frick, Baxter, Markowska, Olton, & Price, 1995; Gallagher & Pelleymounter, 1988; Rodgers, Sindone, & Moffat, 2012). Cognitive decline in aging is also linked to changes in HP gene expression including an upregulation in the gene for Apolipoprotein D (Blalock et al., 2003) as well as immediate early genes (Lanahan, Lyford, Stevenson, Worley, & Barnes, 1997). Moreover, electrophysiological studies show age-correlated shifts in HP place-cell dynamics and Ca2+ homeostasis (Barnes, Suster, Shen, & McNaughton, 1997; Foster & Norris, 1997). Altogether, HP-dependent functions such as memory formation, memory consolidation, context and spatial memory (Morris, Garrud, Rawlins, & O’Keefe, 1982; O’Keefe & Dostrovsky, 1971) are at increased susceptibility to impairment with advanced age.

In spite of their relatively high metabolic rate, body temperature, and blood glucose— factors that contribute to decreased lifespan in mammals—birds appear to have physiological advantages that allow them to live up to three times longer than mammals of equivalent sizes (Austad, 1997; Holmes, Flückiger, & Austad, 2001). Because of their relatively long lifespan and successful adaptations to aging compared to laboratory rodents, avian species may be promising for modeling resilience to senescence.

Many songbird species (Order Passeriformes) possess exceptional spatial memory capabilities. Some memorize and recall thousands of sites where they have cached food (Gould-Beierle & Kamil, 1999; Salwiczek, Watanabe, & Clayton, 2010). In an experimentally-controlled setting, zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) exhibit the ability to effectively learn and recall food locations in a modified version of the Morris water maze and other spatial assays (Mayer, Watanabe, & Bischof, 2010; Sanford & Clayton, 2008). Importantly, these tasks have been shown to require use of the avian HP (Bischof, Lieshoff, & Watanabe, 2006; Mayer et al., 2010; Patel, Clayton, & Krebs, 1997; Watanabe & Bischof, 2004), a structure functionally homologous to the mammalian HP (Bingman, 1992; Colombo & Broadbent, 2000). While age-related deficits in spatial memory have been demonstrated in the non-songbird homing pigeon (Coppola, Flaim, Carney, & Bingman, 2015), there have been no previous studies of aging and spatial learning and memory in songbirds.

To explore the effects of age and sex on spatial memory function in a songbird, we adapted a previously used task that involves acquisition and recall of a food reward in a 4-arm maze (Rensel, Salwiczek, Roth, & Schlinger, 2013). This particular task demands that animals use place-learning strategies involving allocentric cues to locate a reward. Additionally, we considered the possibility that age or sex differences in cognitive function would be correlated with changes in HP gene expression at the time of memory retrieval. We examined mRNA expression of two genes in the HP of all test birds. The first gene we examined was ApoD, the gene coding for apolipoprotein D, for which levels of expression have been shown to be an important and potent marker of aging and degeneration within the mammalian brain (Dassati, Waldner, & Schweigreiter, 2014; de Magalhães, Curado, & Church, 2009; Lee, Weindruch, & Prolla, 2000; Loerch et al., 2008). Although the HP has been the focus of relatively few studies, age-coupled increases in ApoD expression have been detected in the HP of humans (Ordóñez et al., 2012) with females showing a greater increase in expression than males. As a measure of HP activity across groups, we also measured expression of Egr-1 (known as ZENK in songbirds), an immediate early gene (IEG) upregulated in the HP by spatial learning and memory tasks (Bischof et al., 2006; Brito, Britto, & Ferrari, 2006; Knapska & Kaczmarek, 2004; Shimizu, Bowers, Budzynski, Kahn, & Bingman, 2004).

Methods

Subjects

Zebra finches from a colony at UCLA were used in these experiments. In Experiment 1, two groups of adult male (n=4 each) and female (n=4 each) zebra finches between the ages of 150–350 days were used to assess memory after a 5- or 10-day retention interval (total n=16). In Experiment 2, birds of both sexes (n=5/sex) between the ages of 110–135 days (start of reproductive age) were tested as a “young” group, while aged birds (n=6 males; n=5 females) between the ages of 1440–2510 days were used as an “old” group. There was a trend among the aged birds for males to be older than females (t9 = 2.4, p = .06), but young males and females did not differ in age. This trend is due to the limited availability of aged birds in the aviary. In the wild, zebra finches are thought to live up to 3 years (~1100 days), though birds in captivity typically live from 1825–2555 days of age (Austad, 1997). Prior to being separated just before the start of training, birds were housed in a communal, co-sex aviary (max of 40 birds/aviary) under a 14:10 lights-on/lights-off cycle, provided with ad libitum food, water, grit, cuttlebone and egg supplement. All experimental protocols were in compliance with and approved by the UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee.

Behavioral Testing

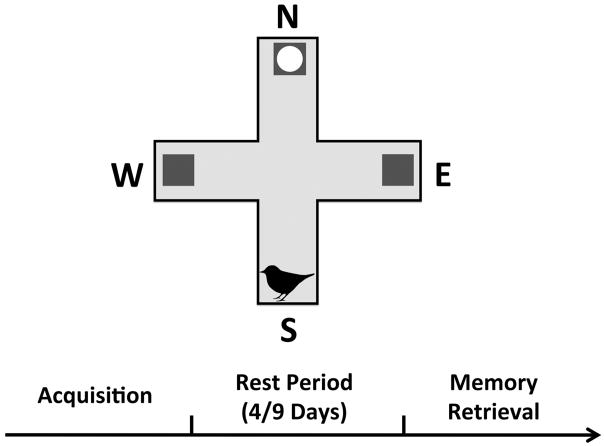

A schematic of the behavioral testing procedure can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Task schematic. Across several days, birds were trained to learn the spatial location of a food reward. Each arm, with the exception of the start arm, had a food cup at its end (gray square), but only the food cup in one spatial location had accessible food (gray square with circle inside of it). On each trial, animals were started from a different arm. Once animals reached criterion acquisition performance, there was a rest period of 4 or 9 days before their retention of the spatial location of the food reward arm was assessed in a single retrieval test session.

Single Housing and Maze Acclimation

As zebra finches are highly gregarious, all birds were acclimated to separation from other birds by being held within individual holding cages inside their home vivarium for 2 days prior to beginning maze acclimation. During this time, animals were also acclimated to eating from the experimental food cups that were to be used in the maze (22 X 22 X 20 mm), by placing a food cup filled with ad libitum grit and cuttlebone, in the cage. They were also handled daily, for 3 mins, to acclimate them to handling. During the next two days, the animals were food restricted from 5:00pm–8:00am, in which the food cup was removed from the holding cage, followed by a 3-hr period of acclimation to the maze in the morning. During the acclimation period, the experimental food and water cups were placed in the center of the maze, while food seeds were spread equally at the ends of each maze arm in order to encourage maze exploration and foraging behavior without associating a certain arm with a food source. The plus-maze, previously used successfully by our lab to assess spatial memory capability in this species (Rensel et al., 2013), consists of a Plexiglas frame surrounded by 1-mm mesh, permitting external visual cues of the testing room (3.35 X 3 m). Visual cues remained constant throughout all acclimation and testing sessions. Visual cues on the walls were not at the ends of arms to discourage the use of non-spatial learning strategies. At the conclusion of each acclimation session, birds were returned to their holding cage. Filled food cups were given to the animals from an hour after acclimation until the food restriction time.

Acquisition

After the two-day acclimation period, the animals began the acquisition phase, where they learned that one of the four arms contained food (Figure 1). Prior to each training day, birds underwent overnight food restriction (5:00pm–8:00am), which included close monitoring of animal condition. In cases where a bird appeared stressed by the food deprivation, the food-restriction period was reduced (2–3 hours) accordingly.

One constant reward arm (1, 2, 3, or 4) was designated for each animal to be used throughout all sessions. For each group, reward arm assignment was counter-balanced, where at least one subject from each group was assigned to each reward arm. The reward arm contained the experimental food cup at its end with accessible seeds, while the others contained identical food cups with transparent tops rendering the food inaccessible.

Each animal experienced one 30-min behavioral session per day, which was capped at 10 trials. For all trials, behaviors were scored by a single observer seated hidden from the bird’s view. If an animal failed to complete 10 trials, but had finished at least 6 trials by the 30-minute mark, a 10-minute time extension was given. For each trial, the animal was placed at the end of a randomized starting arm and was allowed to make one move into an arm, either moving straight, or making a left or right turn. The arm was considered chosen when the animal’s entire body entered the arm. Upon reaching its selected arm, the bird was allowed to eat the seeds or explore the arm for 10 seconds, the end of the trial being signaled by the room’s light turning off. Between trials the bird was removed from the maze and was placed in a new, randomly determined, starting arm. The starting arm of each trial was selected using a random number generator, coded so that no arm was chosen more than twice consecutively, ensuring that each session consisted of a maximum of 4 trials with the same starting arm. At the conclusion of each session, the bird was returned to its holding cage. To avoid creating an association between food availability in the holding cage and completion of the session, potentially damaging to maze performance, the food cup was replaced in the holding cage an hour after completion of the session.

The number of correct choices out of the total number of trials completed within the session was used to calculate the percent accuracy. Animals moved onto the next phase of training when they reached the acquisition criterion. Criterion was reached when the subject received 80% accuracy or higher on two consecutive sessions (i.e. days). Thus, the animal would continue to perform the sessions on each day until it met criterion. Trials omitted due to lack of performance (no movement in the maze after 5 mins) and haphazard flights when the room was illuminated were recorded but did not count towards the trial total.

Retrieval

Once each animal reached the acquisition criterion, it was returned to its holding cage with the same diet protocol as during cage acclimation but without food restriction. For the 10-day retrieval group, animals were given a 9-day rest period followed by a retrieval session on the tenth day (with food restriction reinitiated the evening prior to testing). During the rest days, the animals were handled for 3 min/day during the last 4 days before the retrieval test day. Similarly, the 5-day retrieval group animals were given a 4-day rest period where the animals were handled each day and tested on day 5. In experiment two, all birds were exposed to the 5-day retrieval protocol. Procedures for the retrieval session were identical to those employed during the day before the test. acquisition, and animals were food restricted

Tissue Collection

Brain tissue was collected immediately after the animals completed the retrieval session. Prior to rapid decapitation, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. Both sides of the HP were dissected utilizing stereotaxic coordinates provided in the zebra finch atlas (Nixdorf-Bergweiler & Bischof, 2007). Dissected HP tissues were directly frozen on a foil plate in a container with dry ice and stored in the -80°c freezer.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

ApoD and Egr-1 expression in the zebra finch HP were evaluated using qPCR with GAPDH as the control housekeeping gene and using laboratory procedures described previously (Fuxjager, Barske, Du, Day, & Schlinger, 2012). Collected tissue was initially extracted for RNA using RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) and verified for RNA concentration and A260/280 via Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). RNA samples were reverse transcribed into cDNA with Transcriptase II (Promega). QPCR reactions were performed on the cDNA samples in an ABI 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Primers for ApoD (forward, 5′-TCTCCTTGTTGACCACCTTG; reverse, 5′-TGGGGAATGGTACGAGATAGAG), Egr-1 (forward, 5′-AGAAGCCCTTTCCAGCTCTT; reverse, 5′-TTCAGTTCTTGGGAGCCAGT), and GAPDH (forward, 5′-TGACCTGCCGTCTGGAAAA; reverse, 5′-CCATCAGCAGCAGCCTTCA) were designed from the zebra finch genome.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v20). Percent accuracy was calculated as the number of correct responses out of the total number of trials completed per session (max = 10), excluding the number of omitted trials. While not included in the total number of trials used to calculate percent accuracy, the number of omitted and completed trials per session were recorded and served as indices of task motivation. The criterion for all groups required the animals to achieve at least 80% accuracy on two consecutive acquisition sessions before proceeding to the rest period. For Experiment 1, analysis of days to criterion and trials to criterion was completed using individual sample t-tests. Repeated measure ANOVA was used to analyze accuracy across the first three days, the minimum number of days any bird took to reach criterion. For Experiment 2, days and trials to criterion of young and old, male and female, zebra finches were analyzed with factorial ANOVA. Differences in accuracy across training days were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA. For both behavioral studies, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare retrieval session accuracy, number of trials completed, and number of omissions, as the distribution of the data did not conform to parametric assumptions. For these analyses each age/sex combination were considered separate groups unless otherwise noted. Delta CT values for gene expression data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA.

Results

Behavioral Results

Experiment 1: Sex Differences in Spatial Learning Amongst Adult Birds

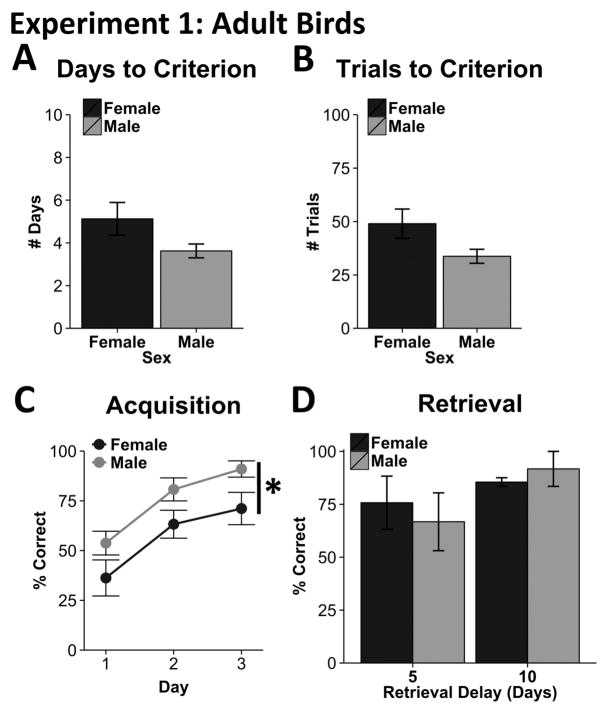

Experiment 1 examined sex differences in spatial learning and memory among middle-aged adult zebra finches in a 4-arm maze. Although there were trends for males to outperform females, there was no significant effect of sex on the number of days (t14 = −1.80, p = .09) or number of trials (t14 = −2.01, p = .064) the birds took to reach the learning criterion (Figure 2A; 2B). The average days and average trials to criterion were 3.6 days and 33.8 trials for males and 5.1 days and 49 trials for females. We next assessed the percent accuracy across the first three days of training, the minimum number of days completed by any one animal before reaching criterion, because this is the period where the first gains in learning are to be found. We observed a significant increase in accuracy across days (F2,28 = 27.54, p < .001; Figure 2C), demonstrative of the animals’ ability to learn the task in this early stage. Additionally, we observed a significant effect of sex (F1,14 = 5.55, p = .03), with no sex by day interaction (F2,28 = .04, p = .96). Here, male zebra finches achieved significantly higher accuracy across the three days (Figure 2C). To assess possible motivational differences associated with animal performance, we analyzed the total number of completed trials as well as omitted trials during the first three days of training. Male and female zebra finches did not differ in the number of omitted trials (U = 24, p = .39) or in the number of trials completed on the first three days (U = 26.5, p = .57; not illustrated). Thus, increased accuracy amongst male zebra finches is unlikely to be due to non-specific motivational changes

Figure 2.

Behavioral Results for Experiment 1. Adult male and adult female zebra finches did not differ with respect to the total number of days (A) or trials (B) that it took them to reach the learning criterion. However, when accuracy was examined across the first 3 days of training, males consistently outperformed females (C). Males and females did not differ with respect to accuracy in the final retrieval test (D). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Asterisk signifies significance of main effect: p<.05.

There was no effect of group on accuracy during the retrieval test ( , p = .38; Figure 2D). Thus, all birds appear to remember the task equally after a 5- or 10-day delay.

Experiment 2: Sex Differences Across the Lifespan

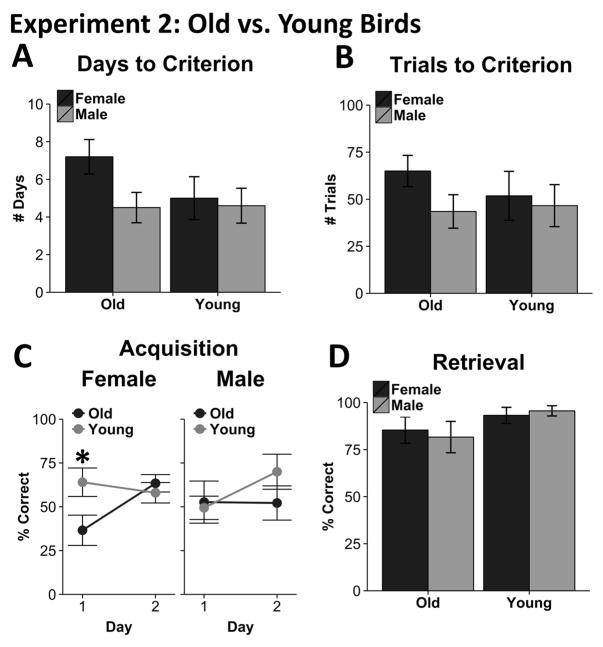

In Experiment 1, it was found that adult male zebra finches outperformed female zebra finches in a spatial memory task. Because spatial learning is affected in senescence, we next examined how spatial learning and memory change across the zebra finch lifespan by comparing young and old birds. Examining the days required to reach the learning criterion, we detected no effect of sex (F1,17 = 2.68, p = .12), age (F1,17 = 1.23, p = .28) or sex by age interaction (F1,17 = 1.48, p = .24; Figure 3A). Similarly, on the number of trials to criterion, there was no effect of sex (F1,17 = 1.64, p = .22), age (F1,17 = .24, p = .63), or sex by age interaction (F1,17 = .61, p = .45; Figure 3B). The average days and average trials to criterion were 5.29 days (min = 3, max = 10) and 51.33 trials (min = 12, max = 99), respectively.

Figure 3.

Behavioral Results for Experiment 1. No differences were observed amongst age/sex groups in terms of the number of days (A) or trials (B) that it took to reach the learning criterion. However, when accuracy was examined across the first 2 days of training, females, but not males, showed age-related differences. Females showed a significant day x age interaction and subsequent analysis revealed that young females out performed old females on the first, but not the second, day of training (C). No differences were observed amongst groups during the retrieval test. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Asterisk signifies significance: p<.05.

As in Experiment 1, we next examined accuracy during early learning phases, where sex differences were most pronounced (Figure 3C). We detected a significant day by sex by age interaction for accuracy across the first two days of training, the minimum number of training days completed by any animal in this group (F1,17 = 7.63, p = .01). To explore this interaction further, accuracy data for males and females was analyzed separately. Importantly, although females demonstrated a significant interaction between day and age (F1,8 = 14.09, p < .01), for males, there was neither a day by age interaction (F1,9 = 1.58, p = .24) nor a main effect of age (F1,9 = .393, p = .546). Specifically, when we examined females across individual days we found that young females outperformed old females on the first, but not the second day (day 1: t8 = 2.31, p = .05; day 2: t8 = .71, p = .5; Figure 3C). These differences are unlikely to be due to differences in motivation, as males and females did not differ in the number of omitted trials (U = 4.5, p = .29), or the number of trials completed (U = 55, p = 1) on the first two days (not illustrated).

On the retention-session accuracy, there was also no effect of age or sex on accuracy ( , p = .619; Figure 3D). Thus, birds of both ages/sexes were able to remember the task equally well.

Gene Expression Results

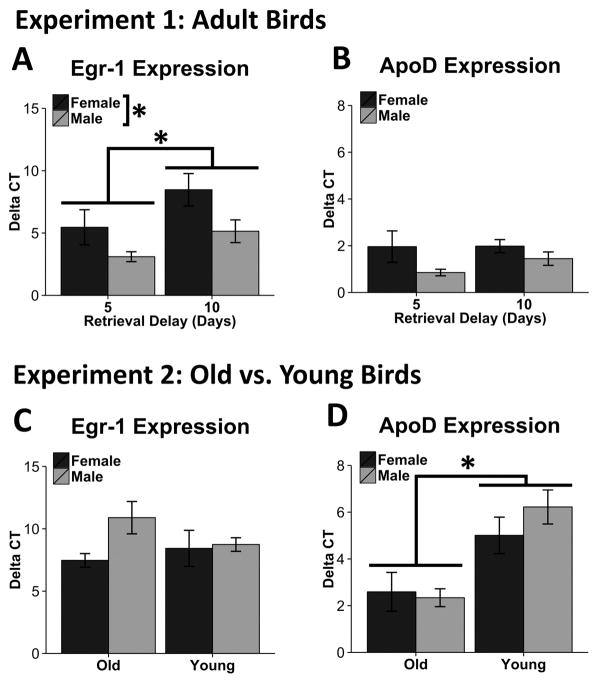

Experiment 1

Expression of the immediate early gene Egr-1 in the hippocampus at the time of memory retrieval was used as an index of HP activation. In Experiment 1, HP Egr-1 expression was significantly greater in females than in males (F1,12 = 6.96, p = .02; Figure 4A). Compared to the 5-day retention group, the 10-day group also expressed significantly higher HP Egr-1 (F1,12 = 5.50, p = .04). However, there was no sex by group interaction (F1,12 = .20, p = .66; Figure 4A). With respect to ApoD expression, there was no effect of sex (F1,12 = 4.26, p = .06), retention delay group (F1,12 = .60, p = .45), or sex by delay group interaction for ApoD expression. (F1,12 = .52, p = .49), in adult zebra finches (Figure 4B)

Figure 4.

HP Gene Expression Results for Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiment 1, there were significant main effects of both age and sex on Egr-1 expression following retrieval (A), where female birds expressed more HP Egr-1 than did males, and birds tested for retrieval after 10 days expressed more Egr-1 than birds tested after 5 days. In Experiment 1, no differences were observed in HP ApoD expression (B). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. In Experiment 2, no significant differences were observed between groups with respect to Egr-1 expression (C). Young birds, regardless of sex, expressed significantly greater levels of ApoD than old birds (D). Asterisk signifies significance: p<.05.

Experiment 2

In Experiment 2, HP Egr-1 expression did not differ between the two sexes (F1,16 = 2.68, p = .12) or age groups (F1,16 = .27, p = .61). Additionally, there was no sex by age interaction (F1,16 = 1.87, p = .19; Figure 4C).

In Experiment 2, we identified an overall age effect with young zebra finches expressing greater ApoD expression than old birds (F1,16 = 21.90, p < .001; Figure 4D). There was no effect of sex (F1,16 = .51, p = .48) or a sex by age interaction (F1,16 = 1.19, p = .29; Figure 4D).

Discussion

Though several previous studies have explored spatial cognition in birds (Bischof et al., 2006; Coppola et al., 2015; Mayer et al., 2010; Rensel et al., 2013; Salwiczek et al., 2010; Watanabe & Bischof, 2004), this is, to our knowledge, the first instance where sex and age effects on spatial learning as well as HP gene expression have been demonstrated in an avian model. We found that middle-aged male birds are more proficient during the acquisition phase of a spatial learning task, though they did not differ from females in their ability to retain an already formed spatial memory for up to 10 days. Moreover, these effects appear to be mediated by age, as sex differences were not observed in young birds. Nevertheless, older birds did not display in overall impairment in learning, and were just as able as young birds to retain a spatial memory across several days. Hence, zebra finches appear somewhat resistant to senescence, although learning decrements may have been revealed with a more difficult task.

It is important to first recognize that despite a significant body of work focusing on the effects of aging on cognition, most studies utilize laboratory rats and mice, which are relatively small and short-lived mammalian models. Whereas body size and longevity generally correlate in mammals, this is not the case in birds; birds generally live up to three times longer than do mammals of a similar size (Holmes & Austad, 1995; Holmes et al., 2001; Holmes & Ottinger, 2003). Captive mice, for example, live for up to 4 years, whereas a comparably-sized captive songbird, the zebra finch, lives up to 9 years (Holmes & Ottinger, 2003). Though birds are susceptible to diseases and injuries that afflict mammals, they demonstrate relatively lower rates of physiological decline (Holmes & Austad, 1995; Holmes et al., 2001; Holmes & Ottinger, 2003; Munshi-South & Wilkinson, 2010). Therefore, zebra finches may make excellent models for human longevity and offer insight into the mechanisms of senescence and successful aging.

The assay developed in this experiment exploited zebra finch ground-feeding/foraging behavior and required the birds to use spatial reference or place memory. That is, in order to find the correct food location, birds were required to apply external spatial cues relative to their randomized starting positions. This learning strategy is distinct from response or cued spatial learning where animals only learn a motor response (e.g., always turning left or right) or go to a previously marked goal (e.g., always going to the cup with the red flag) to obtain reward (Gallagher & Pelleymounter, 1988). However, it is important to note that certain extra-maze cues might have been employed in the service of a cued learning strategy. Although extra-maze (test room) cues were arranged in ways that discouraged their direct use (e.g., wall cues were not placed directly above the end of the reward arm), it is difficult to completely rule out such a strategy. Only future experiments that test cued spatial learning will be able to confirm if this current paradigm truly required the animals to use spatial reference memory.

Nonetheless, by testing this protocol on adult male and female zebra finches, we observed a sex difference in spatial cognitive abilities. Similar to human and rodent studies (Astur, Ortiz, & Sutherland, 1998; Frick et al., 1995; Jones, Braithwaite, & Healy, 2003; Markowska, 1999; Voyer, Voyer, & Bryden, 1995), male zebra finches consistently performed at higher percent accuracy in acquiring the spatial task compared to their female counterparts. Though zebra finch females were eventually able to reach criterion and were able to perform equally well on the retention session, they did so at a slower rate. In addition to the slower learning rate, there was a trend towards female birds taking more days and trials to reach criterion. Given that there were no differences in motivational indices (the number of completed trials and omissions), this sex effect was not confounded by non-mnemonic factors such as differences in activity or physical state. Furthermore, other studies in rats have provided evidence that males and females tend to rely on different spatial strategies (Kanit et al., 2000; Tropp & Markus, 2001). Therefore, the initial poor performance of females might have been a reflection of those birds utilizing cues and spatial strategies that were not appropriate during the beginning of the training. Sexually dimorphic spatial abilities have been well documented in mammalian species, where males reliably outperform females (Astur et al., 1998; Frick et al., 1995; Jones et al., 2003; Markowska, 1999; Voyer et al., 1995). Recently, we also reported on sex-differences in acquisition and recall in a food-caching corvid, Western scrub jays (Aphelacoma californica) that suggested males and females might utilize different strategies for learning these tasks (Rensel, Ellis, Harvey, & Schlinger, 2015). Thus, sex differences in spatial learning are likely to be phylogenetically quite common.

Sex differences in behavior, including in cognitive spatial abilities, can result from organizational and/or activational effects of sex hormones (Isgor & Sengelaub, 1998; Neave, Menaged, & Weightman, 1999; Sherry & Hampson, 1997; Williams, Barnett, & Meck, 1990). Some sex differences in rodent spatial cognition seem to arise only after puberty (Bucci, Chiba, & Gallagher, 1995; Kanit et al., 2000; Krasnoff & Weston, 1976; Markowska, 1999; Warren & Juraska, 1997). Additionally, sex differences in spatial/contextual fear learning in rodents appear only during only certain phases of the female estrous cycle (Cushman, Moore, Olsen, & Fanselow, 2014). Such findings suggest an activational effect of reproductive hormones. The sex differences we observed in the middle-aged adult zebra finches of Experiment 1 were not entirely mirrored in Experiment 2 that included the testing of very young adults, which did not display sex-differences in spatial learning. It may be the case that cognitive deficits in female birds appear not long after reaching adulthood. Additionally, although birds of the age we chose as young adults are sexually mature, it is possible that cumulative effects of long term gonadal steroid exposure are important for establishing sex differences in patterns of spatial learning and memory.

Several bird species cache food and recall numerous cache sites many months following the storage of food (Gould-Beierle & Kamil, 1999; Mayer et al., 2010; Salwiczek et al., 2010). Such exceptional cognitive ability has obvious survival advantages that would apply to both males and females and to birds of all ages. Our observation of minimal effects of age on spatial cognition in the zebra finch is in keeping with the idea that this cognitive function requires considerable resilience against the effects of age. It is also possible that our 4- and 9- day recall tests were insufficiently challenging to reveal sex or age effects. Alternatively, various forms of learning and memory that depend upon the hippocampus appear to become hippocampal independent with time (Anagnostaras, Maren, & Fanselow, 1999), and this may explain why sex and age-related differences were only observed when examining accuracy during early training. It is unclear for how long the avian HP is required for remembering spatial locations. Nevertheless, the accuracy of old female zebra finches was significantly worse on the first day of training compared to young females, a pattern not seen in males, suggesting that age influences spatial cognitive ability differently according to sex. These data point to the existence of age-related deficits in reference learning that depend on the sex of the zebra finch.

Egr-1, (known as ZENK in songbirds), is an important transcription factor and immediate-early gene that shows rapid upregulation in activated hippocampal circuits involved in learning and memory in both mammals and birds (Knapska & Kaczmarek, 2004; Shimizu et al., 2004; Veyrac et al., 2013), including zebra finches (Bischof et al., 2006; Mayer et al., 2010). In zebra finches, HP IEG expression is enhanced in learning and memory tasks requiring use of spatial cues (Mayer & Bischof, 2012). Interestingly, we found that expression was greater during “middle-age” in the HP of females compared to males. This finding is consistent with previous studies in rodents that have observed increased HP activation to be correlated with deficits in spatial learning and memory, using both IEG expression and electrophysiological recording (Haberman, Koh, & Gallagher, 2017; Wilson, Ikonen, Gallagher, Eichenbaum, & Tanila, 2005). Perhaps greater HP activation reflects an imbalance in HP tuning. These results are also in line with observations in other regions of the songbird brain where IEG expression is elevated in females (Krentzel & Remage-Healey, 2015). Such a sex-difference could result from differences in actions of estrogens, which have been shown to alter behavior on a similar HP-dependent spatial memory task (Rensel et al., 2013), potentially by altering the balance of HP excitability. Alternatively, and as discussed above, it may be that females employ somewhat different strategies to solve the task (Kanit et al., 2000; Tropp & Markus, 2001), engaging the HP to a greater degree resulting in increased Egr-1 expression, or perhaps in order to compensate for a tendency towards deficient spatial processing.

Egr-1 expression was also consistently higher in the HP of both males and females required to recall the reward arm after the 10- vs 5-day long retention period. Although there was no difference in retention accuracy between the 5- and 10-day groups, this observation suggests a greater degree of HP activation, perhaps a reflection of the increased difficulty of the task or a change in strategy utilized to complete the task. Such an interpretation is consistent with females showing greater hippocampal Egr-1 expression despite equivalent spatial learning performance.

Had hippocampal function deteriorated with age, we might have expected a difference between young and old birds in HP expression following the recall test. However, we found no such difference, consistent with the absence of marked performance differences, at least at the time of retention, due to age. These results provide evidence that the HP of older zebra finches may be less susceptible to physiological degeneration.

The decrease in ApoD expression with age is of particular interest in these experiments. Our results would seem to corroborate earlier speculation that increased ApoD leads to a decline in neural function. Aged birds showed little to no difference in spatial learning, performing similar to the younger adults on the memory tests, and unlike mammals, did not have a large increase in ApoD expression. However other more recent evidence pertaining to ApoD shows that ApoD knockout (KO) dramatically increases the susceptibility of an organism to both premature aging and neurodegeneration (Sanchez et al., 2015), suggesting that the relationship between senescence and aging is not of a simple monotonic nature. ApoD is also expressed in the embryonic chicken brain (Ganfornina et al., 2005), when neuroproliferation is pronounced. Neurogenesis persists in the adult songbird HP (Barnea & Nottebohm, 1994). Thus, it is possible that in the early adult stage an elevated degree of neuroplasticity is present in the songbird HP with an associated higher expression of ApoD. As the birds age, this neuroplasticity may decrease along with ApoD expression, though with little impact on the cognitive functions measured here.

In contrast to what has been found in mammals, we observed no sex differences in expression of ApoD in zebra finches. One of the theories behind the sex differences in ApoD expression observed in mammals is that it is precipitated by the onset of menopause later in life (Ordóñez et al., 2012). ApoD expression has been shown to be sensitive to estrogens and progesterone (Lambert, Provost, Marcel, & Rassart, 1993; Simard, Veilleux, de Launoit, Haagensen, & Labrie, 1991) and testosterone (Simard et al., 1991). Evidence for the idea that the drop in estrogen as a result of menopause in mammals may be mediating changes in ApoD may be supported by our data as avian species remain reproductively fertile well into the later stages of life.

ApoD’s expression has also been tightly linked to neurodegeneration, particularly in diseases associated with an increase in oxidative stress such as Alzheimer’s disease (Muffat & Walker, 2010). Theories behind the maladaptive changes and ApoD KO models have shown dramatic reduction in the ability to respond to oxidative stress (Ganfornina et al., 2008; Sanchez et al., 2006) while double knock-in models have shown dramatic increase in the ability to respond to oxidative stress (Muffat & Walker, 2010). ApoD expression may also therefore be tightly regulated by the amount of oxidative stress experienced by the organism. The decrease in ApoD expression and lack of observable detriment to memory task from age may suggest the possibility that avian species may have additional or alternative oxidative stress management capabilities that may explain how many small bird species are able to live so long despite having both a small size and fast metabolism as opposed to the similarly sized mammalian counterparts that have markedly shorter lifespans.

Whatever the case, aged zebra finches are capable of retaining significant HP-dependent learning and memory function and IEG activation, while simultaneously showing decreased levels of ApoD mRNA associated with neural decline. These birds may represent excellent models to explore natural mechanisms that protect the brain from the effects of aging (Schlinger & Saldanha, 2005). As males and females differ in HP gene expression and in some cognitive function, sex will be an important consideration in exploring HP physiology and function in the future. It seems clear that ApoD will be a key target for subsequent investigation in this fascinating group of birds.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Rensel, Devon Comito, Devaleena Pradhan and Matt Fuxjager for assistance with data collection and analysis. Supported by RO1 MH061994 (BAS) and F31MH185207-02 (ZTP).

References and Literature Cited

- Anagnostaras SG, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Temporally graded retrograde amnesia of contextual fear after hippocampal damage in rats: within-subjects examination. J Neurosci. 1999;19(3):1106–1114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01106.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astur RS, Ortiz ML, Sutherland RJ. A characterization of performance by men and women in a virtual Morris water task: a large and reliable sex difference. Behav Brain Res. 1998;93(1–2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austad SN. Birds as Models of Aging in Biomedical Research. ILAR J. 1997;38(3):137–141. doi: 10.1093/ilar.38.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea A, Nottebohm F. Seasonal recruitment of hippocampal neurons in adult free-ranging black-capped chickadees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(23):11217–11221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA. Neurological and behavioral investigations of memory failure in aging animals. Int J Neurol. 1987;21–22:130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Nadel L, Honig WK. Spatial memory deficit in senescent rats. Can J Psychol. 1980;34(1):29–39. doi: 10.1037/h0081022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Suster MS, Shen J, McNaughton BL. Multistability of cognitive maps in the hippocampus of old rats. Nature. 1997;388(6639):272–275. doi: 10.1038/40859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingman VP. The importance of comparative studies and ecological validity for understanding hippocampal structure and cognitive function. Hippocampus. 1992;2(3):213–219. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof HJ, Lieshoff C, Watanabe S. Spatial memory and hippocampal function in a non-foodstoring songbird, the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) Rev Neurosci. 2006;17(1–2):43–52. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.1-2.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock EM, Chen KC, Sharrow K, Herman JP, Porter NM, Foster TC, Landfield PW. Gene microarrays in hippocampal aging: statistical profiling identifies novel processes correlated with cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2003;23(9):3807–3819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03807.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito I, Britto LR, Ferrari EA. Classical tone-shock conditioning induces Zenk expression in the pigeon (Columba livia) hippocampus. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120(2):353–361. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci DJ, Chiba AA, Gallagher M. Spatial learning in male and female Long-Evans rats. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109(1):180–183. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(1):30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Iliffe S. Dementia. BMJ. 2009;338:b75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo M, Broadbent N. Is the avian hippocampus a functional homologue of the mammalian hippocampus? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(4):465–484. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola VJ, Flaim ME, Carney SN, Bingman VP. An age-related deficit in spatial-feature reference memory in homing pigeons (Columba livia) Behav Brain Res. 2015;280:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman JD, Moore MD, Olsen RW, … Fanselow MS. The role of the δ GABA(A) receptor in ovarian cycle-linked changes in hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. Neurochem Res. 2014;39(6):1140–1146. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassati S, Waldner A, Schweigreiter R. Apolipoprotein D takes center stage in the stress response of the aging and degenerative brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(7):1632–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhães JP, Curado J, Church GM. Meta-analysis of age-related gene expression profiles identifies common signatures of aging. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(7):875–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Yeo RA, Brooks WM, Baumgartner RN, Sutherland RJ. The aging hippocampus: cognitive, biochemical and structural findings. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(12):1344–1351. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TC, Norris CM. Age-associated changes in Ca(2+)-dependent processes: relation to hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Hippocampus. 1997;7(6):602–612. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:6<602::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Baxter MG, Markowska AL, Olton DS, Price DL. Age-related spatial reference and working memory deficits assessed in the water maze. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16(2):149–160. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxjager MJ, Barske J, Du S, Day LB, Schlinger BA. Androgens regulate gene expression in avian skeletal muscles. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Pelleymounter MA. Spatial learning deficits in old rats: a model for memory decline in the aged. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9(5–6):549–556. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina MD, Do Carmo S, Lora JM, Torres-Schumann S, Vogel M, Allhorn M, … Sanchez D. Apolipoprotein D is involved in the mechanisms regulating protection from oxidative stress. Aging Cell. 2008;7(4):506–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganfornina MD, Sánchez D, Pagano A, Tonachini L, Descalzi-Cancedda F, Martínez S. Molecular characterization and developmental expression pattern of the chicken apolipoprotein D gene: implications for the evolution of vertebrate lipocalins. Dev Dyn. 2005;232(1):191–199. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazova I, Vlcek K, Laczó J, Nedelska Z, Hyncicova E, Mokrisova I, … Hort J. Spatial navigation-a unique window into physiological and pathological aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2012;4:16. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2012.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould-Beierle KL, Kamil AC. The effect of proximity on landmark use in Clark’s nutcrackers. Anim Behav. 1999;58(3):477–488. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman RP, Koh MT, Gallagher M. Heightened cortical excitability in aged rodents with memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;54:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DJ, Austad SN. Birds as animal models for the comparative biology of aging: a prospectus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(2):B59–66. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DJ, Flückiger R, Austad SN. Comparative biology of aging in birds: an update. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36(4–6):869–883. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DJ, Ottinger MA. Birds as long-lived animal models for the study of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2003;38(11–12):1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isgor C, Sengelaub DR. Prenatal gonadal steroids affect adult spatial behavior, CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cell morphology in rats. Horm Behav. 1998;34(2):183–198. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Braithwaite VA, Healy SD. The evolution of sex differences in spatial ability. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117(3):403–411. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanit L, Taskiran D, Yilmaz OA, Balkan B, Demirgören S, Furedy JJ, Pögün S. Sexually dimorphic cognitive style in rats emerges after puberty. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52(4):243–248. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapska E, Kaczmarek L. A gene for neuronal plasticity in the mammalian brain: Zif268/Egr-1/NGFI-A/Krox-24/TIS8/ZENK? Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74(4):183–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnoff A, Weston LM. Puberal status and sex differences: activity and maze behavior in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1976;9(3):261–269. doi: 10.1002/dev.420090310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentzel AA, Remage-Healey L. Sex differences and rapid estrogen signaling: A look at songbird audition. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2015;38:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J, Provost PR, Marcel YL, Rassart E. Structure of the human apolipoprotein D gene promoter region. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1172(1–2):190–192. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90292-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanahan A, Lyford G, Stevenson GS, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Selective alteration of long-term potentiation-induced transcriptional response in hippocampus of aged, memory-impaired rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17(8):2876–2885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02876.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM. New insights into the dementia epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2275–2277. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CK, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):294–297. doi: 10.1038/77046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister JP, Barnes CA. Neurobiological changes in the hippocampus during normative aging. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(7):829–833. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerch PM, Lu T, Dakin KA, Vann JM, Isaacs A, Geula C, … Yankner BA. Evolution of the aging brain transcriptome and synaptic regulation. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowska AL. Sex dimorphisms in the rate of age-related decline in spatial memory: relevance to alterations in the estrous cycle. J Neurosci. 1999;19(18):8122–8133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08122.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer U, Bischof HJ. Brain activation pattern depends on the strategy chosen by zebra finches to solve an orientation task. J Exp Biol. 2012;215(Pt 3):426–434. doi: 10.1242/jeb.063941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer U, Watanabe S, Bischof HJ. Hippocampal activation of immediate early genes Zenk and c-Fos in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) during learning and recall of a spatial memory task. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;93(3):322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O’Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297(5868):681–683. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muffat J, Walker DW. Apolipoprotein D: an overview of its role in aging and age-related diseases. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(2):269–273. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.2.10433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi-South J, Wilkinson GS. Bats and birds: Exceptional longevity despite high metabolic rates. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neave N, Menaged M, Weightman DR. Sex differences in cognition: the role of testosterone and sexual orientation. Brain Cogn. 1999;41(3):245–262. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergweiler Nixdorf, Barbara E, Bischof Hans-Joachim. A stereotaxic atlas of the brain of the Zebra Finch, Taeniopygia Guttata: with special emphasis on telencephalic visual and song system nuclei in transverse and sagittal sections. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map. Preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain Res. 1971;34(1):171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez C, Navarro A, Pérez C, Martínez E, del Valle E, Tolivia J. Gender differences in apolipoprotein D expression during aging and in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(2):433e411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SN, Clayton NS, Krebs JR. Hippocampal tissue transplants reverse lesion-induced spatial memory deficits in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) J Neurosci. 1997;17(10):3861–3869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03861.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensel MA, Ellis JM, Harvey B, Schlinger BA. Sex, estradiol, and spatial memory in a food-caching corvid. Horm Behav. 2015;75:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensel MA, Salwiczek L, Roth J, Schlinger BA. Context-specific effects of estradiol on spatial learning and memory in the zebra finch. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013;100:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers MK, Sindone JA, Moffat SD. Effects of age on navigation strategy. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(1):202.e215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salwiczek LH, Watanabe A, Clayton NS. Ten years of research into avian models of episodic-like memory and its implications for developmental and comparative cognition. Behav Brain Res. 2010;215(2):221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Bajo-Grañeras R, Del Caño-Espinel M, Garcia-Centeno R, Garcia-Mateo N, Pascua-Maestro R, Ganfornina MD. Aging without Apolipoprotein D: Molecular and cellular modifications in the hippocampus and cortex. Exp Gerontol. 2015;67:19–47. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, López-Arias B, Torroja L, Canal I, Wang X, Bastiani MJ, Ganfornina MD. Loss of glial lazarillo, a homolog of apolipoprotein D, reduces lifespan and stress resistance in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16(7):680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford K, Clayton NS. Motivation and memory in zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) foraging behavior. Anim Cogn. 2008;11(2):189–198. doi: 10.1007/s10071-007-0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibel AB. The hippocampus: organizational patterns in health and senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 1979;9(1–2):89–102. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(79)90123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger BA, Saldanha CJ. Songbirds: A novel perspective on estrogens and the aging brain. Age (Dordr) 2005;27(4):287–296. doi: 10.1007/s11357-005-4555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DF, Hampson E. Evolution and the hormonal control of sexually-dimorphic spatial abilities in humans. Trends Cogn Sci. 1997;1(2):50–56. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(97)01015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Bowers AN, Budzynski CA, Kahn MC, Bingman VP. What does a pigeon (Columba livia) brain look like during homing? selective examination of ZENK expression. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118(4):845–851. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard J, Veilleux R, de Launoit Y, Haagensen DE, Labrie F. Stimulation of apolipoprotein D secretion by steroids coincides with inhibition of cell proliferation in human LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51(16):4336–4341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp J, Markus EJ. Sex differences in the dynamics of cue utilization and exploratory behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2001;119(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Shubert T, Zhao C, Gage FH. Exercise enhances learning and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25(38):8680–8685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrac A, Gros A, Bruel-Jungerman E, Rochefort C, Kleine Borgmann FB, Jessberger S, Laroche S. Zif268/egr1 gene controls the selection, maturation and functional integration of adult hippocampal newborn neurons by learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(17):7062–7067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220558110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer D, Voyer S, Bryden MP. Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: a meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(2):250–270. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren SG, Juraska JM. Spatial and nonspatial learning across the rat estrous cycle. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(2):259–266. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Bischof HJ. Effects of hippocampal lesions on acquisition and retention of spatial learning in zebra finches. Behav Brain Res. 2004;155(1):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Barnett AM, Meck WH. Organizational effects of early gonadal secretions on sexual differentiation in spatial memory. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104(1):84–97. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IA, Ikonen S, Gallagher M, Eichenbaum H, Tanila H. Age-associated alterations of hippocampal place cells are subregion specific. J Neurosci. 2005;25(29):6877–6886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1744-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winocur G, Moscovitch M. Hippocampal and prefrontal cortex contributions to learning and memory: analysis of lesion and aging effects on maze learning in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1990;104(4):544–551. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]