Abstract

Despite the critical impact of glaucoma on global blindness, its aetiology is not fully characterised. Elevated intraocular pressure is highly associated with glaucomatous optic neuropathy. However, visual field loss still progresses in some patients with normal or even low intraocular pressure. Vascular factors have been suggested to play a role in glaucoma development, based on numerous studies showing associations of glaucoma with blood pressure, ocular perfusion pressure, vasospasm, cardiovascular disease and ocular blood flow. As the retinal vasculature is the only part of the human circulation that readily allows non-invasive visualisation of the microcirculation, a number of quantitative retinal vascular parameters measured from retinal photographs using computer software (eg, calibre, fractal dimension, tortuosity and branching angle) are currently being explored for any association with glaucoma and its progression. Several population-based and clinical studies have reported that changes in retinal vasculature (eg, retinal arteriolar narrowing and decreased fractal dimension) are associated with optic nerve damage and glaucoma, supporting the vascular theory of glaucoma pathogenesis. This review summarises recent findings on the relationships between quantitatively measured structural retinal vascular changes with glaucoma and other markers of optic nerve head damage, including retinal nerve fibre layer thickness. Clinical implications, recent new advances in retinal vascular imaging (eg, optical coherence tomography angiography) and future research directions are also discussed.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Retinal Vasculature, Retinal Photography

Introduction

Despite the critical impact of glaucoma on global blindness, its aetiology is not fully characterised. It has been recognised that elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) exerts direct mechanical damage to the optic nerve head (ONH).1 2 However, among glaucoma patients, only one-third to half have elevated IOP at the initial stages.3–5 In some, visual field loss continues despite adequate IOP control to normal levels.

Consequently, non-IOP-dependent mechanisms have been proposed. The ‘vascular theory’ of glaucoma hypothesises retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss as a consequence of insufficient blood supply.6 7 Vasospasm and autoregulatory dysfunction have been postulated to reduce ocular blood flow. This role is further supported by the association of glaucoma with vascular diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes,8–10 though discrepancies exist,11 12 and inclusion as part of the primary vasospastic syndrome following its relationship with Raynaud’s phenomenon, autoimmune diseases and migraine.13–16 Nevertheless, ongoing discussion over the influence of ocular perfusion pressure (OPP) on glaucoma recognises the inconsistent findings of the influence of diastolic and systolic OPP in the incidence and progression of glaucoma in large epidemiological studies,5 17–21 which is further complicated by the dynamic relationship between OPP, blood pressure and IOP.22

Both static and dynamic properties of the retinal microcirculation may be implicated in the vascular phenomenon in glaucoma. Study of the retinal microcirculation is thus made possible by the accessibility of retinal vasculature via non-invasive means. Over the past two decades, semiautomated software systems have enabled objective and reliable quantification of geometric components of the retinal vasculature from retinal photography, including retinal vascular calibre, tortuosity, branching angle and fractal dimensions.23 In effect, multiple studies have linked geometric retinal vascular parameters with vascular diseases including ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, stroke and diabetes.24–33

In this review, we summarise recent findings on the relationships between quantitatively measured structural retinal vascular changes with glaucoma and other markers of ONH damage. We further discuss the recent new advances in retinal vascular imaging (eg, optical coherence tomography angiography) and future research directions.

Methods and materials

A comprehensive literature search on PubMed was performed for studies published until August 2016 with keywords ‘glaucoma’, ‘retinal nerve fibre layer thickness’, ‘geometry’, ‘retinal vascular calibre’, ‘tortuosity’, ‘branching angle’ and ‘fractal dimensions’. Combinations of these terms were used as well. Search results were limited to studies published in English and in human subjects only. Selected papers were then reviewed thoroughly and evidence was summarised.

Ocular microcirculation in glaucoma

Owing to the increasing recognition of involvement of vascular phenomena in glaucoma, interest in the presence of retinal microcirculatory changes in glaucoma patients has been raised. Improvement in blood flow and visual field measurements in some eyes following treatment with vasodilating calcium channel blockers34 or carbon dioxide inhalation35 present evidence of vascular autodysregulation. In addition, a recent study showed multiple comparable ocular and systemic vascular alterations in the early stages of patients both with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and normal tension glaucoma (NTG), which were not replicated in controls.36 The idea that a continuum of disturbed circulation exists between the two previously ‘distinct’ disease entities is proposed and further extends the need for evaluation of vascular properties (eg, ocular blood flow).

ONH blood flow is tightly autoregulated to meet the functional and metabolic demands of the retina, including RGC. Technological advancements have made visualisation, direct measurements and quantification of in- vivo ocular blood flow possible, though a gold standard that provides all the relevant information in one reading has yet to be established. Current modes of analysis of this dynamic parameter include, but are not limited to, angiography, laser Doppler techniques, Heidelberg Retina Flowmeter, laser speckle phenomenon and retinal vessel analyser.37 38 MRI can provide not only dynamic blood flow measurement within deep orbital structures but also a non-invasive measurement of intracranial structures.39 Nevertheless, the vast variety of instruments create difficulty for data unification, though a consistent demonstration of decreased average blood flow in some glaucoma patients was found in the retinal,40 41 ONH42 43 and choroidal44 circulations.

Murray’s Principle of Minimum Work established that the vascular network conforms to an ‘optimally’ designed topographical geometry.45 This minimises shear stress and work across vascular network and allows sufficient blood distribution to tissue with the least amount of energy. As blood flow is a function of cardiac output and regulated by relative local resistance, deviations to ideal structure and function of the microcirculation will lead to reduced efficiency and impaired circulatory transport.46 In view of the challenges in dynamic analysis, interest has turned in the direction of the vascular network’s static components, including its design, since they reflect resistance to ocular blood flow and affect function.

Quantitative measurements of retinal vasculature

With the introduction of modern digitalised retinal photography, semiautomated computer-assisted programmes have been developed to objectively and reliably quantify subtle retinal vascular changes from retinal photographs, with focus on calibre measurement. Optimate (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, University of Wisconsin—Madison) and IVAN (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, University of Wisconsin—Madison) softwares analyse digitalised retinal photographs and measure the retinal vessel widths.47 48 With the development of digital retinal photography, newer programs such as Singapore I Vessel Assessment (SIVA)25 and Vessel Assessment and Measurement Platform for Images of the REtina (VAMPIRE)49 softwares have evolved to evaluate novel classes of retinal vascular geometric parameters, including tortuosity, fractal dimension and branching angle, providing comprehensive assessment of retinal vasculature (figure 1). Such development provides an accessible, non-invasive model to study correlations and consequences of microvascular dysfunction in both systemic and ocular diseases.50–52 For example, systemic review has confirmed that wider retinal venular calibres predict stroke,53 and meta-analysis showed independent associations between wider retinal venules and narrower arterioles with increased risk for cardiovascular events in women.54

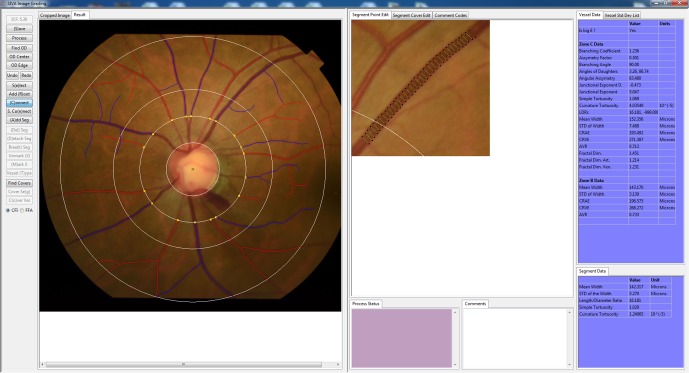

Figure 1.

Quantitative measurement of retinal vasculature from retinal fundus photograph using a computer-assisted program (Singapore I Vessel Assessment (SIVA)).

Retinal vascular calibre

Retinal vascular calibre is measured in terms of central retinal artery equivalent (CRAE), central retinal vein equivalent (CRVE) and arteriovenous ratio (AVR).47 48 CRAE is a summary index reflecting the average width of retinal arterioles, and CRVE is a summary index reflecting the average width of retinal venules. It has been recognised that CRAE and CRVE should be analysed independently, as they reflect distinct systemic vascular disease pathways. AVR is a dimensionless ratio that is used to compensate for magnification differences and refractive error, and its value is non-specific to changes in arterioles, venules or both.

Retinal vascular tortuosity

Retinal vascular tortuosity reflects vessel curvature and is summarised as the ratio between the actual distance a vessel travels from points A to B and the shortest straight-line distance between points A and B.55 A larger tortuosity index indicates more curves in a retinal vessel. Retinal vascular tortuosity can be computed as the integral of the curvature square along the path of the vessel, normalised by the total path length.24 Since this measure is represented as a ratio, its value is dimensionless.56

Retinal vascular bifurcation angle

Retinal vascular bifurcation angle is defined as the first angle subtended between two daughter vessels at a vascular junction. Both retinal arteriolar branching angle and retinal venular branching angle could be derived, and they represent the average branching angle of arterioles and venules, respectively.57

Fractal dimension

Fractal dimension describes how thoroughly a pattern fills two-dimensional spaces and represents a ‘global’ measure that summarises the whole branching pattern of the retinal vascular tree.58 59 It is calculated from a skeletonised line tracing using a box-counting method. Larger values indicate a more complex branching pattern.

Retinal vascular changes associated with glaucoma

Generalised narrowing of the retinal vessels is characteristic of advanced glaucomatous optic nerve damage.60 A number of epidemiological studies have shown association between retinal vascular changes, particularly narrowing in retinal vascular calibre, with glaucoma. Table 1 presents the associations between quantitative retinal vascular parameters with glaucoma in population-based and hospital-based cross-sectional studies.

Table 1.

Associations between quantitative retinal vascular parameters with glaucoma in population-based and hospital-based cross-sectional studies

| Study and year | Study type | Sample size | Method of assessment | Changes in parameters in association with glaucoma | ||||

| Arteriolar calibre | Venular calibre | Fractal dimension | Tortuosity | Branching angle | ||||

| Ciancaglini et al

81

(2015) |

Hospital-based cross-sectional study | N/A | Heidelberg Doppler flowmetry | – | – | Reduced | – | – |

| De Leon et al

72

(2015) |

Hospital-based, cross-sectional study | Any glaucoma: 158 | IVAN | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Gao et al

78

(Handan Eye Study) (2015) |

Population-based cross-sectional study | Healthy: 5788 POAG: 54 PACG: 19 PACS: 731 PAC: 64 |

Optimate | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Yoo et al

79

(2015) |

Hospital-based case-control study | Healthy: 60 HPG: 63 NTG: 82 |

IVAN | Reduced | Not significant | – | – | – |

| Wu et al

82

(Singapore Malay Eye Study) (2013) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 2666 POAG: 87 OHT: 58 |

SIVA | – | – | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Amerasinghe et al

76

(Singapore Malay Eye study) (2008) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 2892 POAG: 88 PACG: 5 NTG: 74 |

IVAN | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Wang et al

77

(Beijing Eye Study) (2007) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Total: 2418 | Manual | Reduced | Not significant | – | – | – |

| Klein et al

80

(Beaver Dam Eye Study) (2004) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Total: 4613 Any glaucoma: 199 |

Optimate | Not significant | Not significant | – | – | – |

| Mitchell et al

75

(Blue Mountains Eye Study) (2004) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 3065 HPG: 38 NTG: 21 OHT: 163 |

Optimate | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Angelica et al

74

(2001) |

Hospital-based, cross-sectional study | Total: 143 | HRT software 1.11, Interactive Means program | Not significant | – | – | – | – |

| Rankin et al

62

(1996) |

Hospital-based, case-control study | Healthy: 7 POAG: 32 NTG: 48 OHT: 19 Suspects: 4 |

Manual | Reduced | – | – | – | – |

| Rader et al

61

(1994) |

Hospital-based, case-control study | Healthy: 206 Any glaucoma: 226 |

Manual | Reduced | – | – | – | – |

| Jonas et al

60

(1989) |

Hospital-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 173 POAG: 281 |

Manual | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

AVR, arteriovenous ratio; COAG, chronic open-angle glaucoma; HPG, high-pressure glaucoma; NTG, normal tension glaucoma; OHT, ocular hypertension; PAC, primary angle closure; PACG, primary angle closure glaucoma; PACS, primary angle closure suspect; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; SIVA, Singapore ‘I’ Vessel Assessment.

Prior to availability of semiautomated machines, retinal vessel calibres in eyes with glaucoma were explored via manual means.60–62 Evidence of decreasing retinal vessel calibre with increasing glaucoma stage was demonstrated, with stronger correlation for arteries than veins. Quadrants with greater ONH damage corresponded with narrower retinal arteries. Regarding this association, two schools of explanations have been postulated. On the one hand, RGC loss has been suggested to lead to vasoconstriction as an adjustment to decreased metabolic needs. This is in line with the observation of retinal arterial narrowings in eyes with non-glaucomatous optic atrophy.62–64 Alternatively, the underlying pathological process leading to RGC loss has been proposed to be related to impaired local autoregulation, vasoactive substance leakage and consequently vasoconstriction.65 On the molecular level, this is supported by elevated biomarkers of oxidative stress in aqueous humour, serum and trabecular meshwork samples of glaucoma patients.66 67 Reactive free radicals scavenge nitrous oxide, an innate vasodilator secreted by smooth muscles that alter vascular tone. Short posterior ciliary artery (SPCA), in particular, has been found to exhibit transient vasospasm on radical exposure in in-vitro models,68 and reduced SPCA blood flow velocities were associated with glaucoma progression.69 Altered systemic vasoreactivity with endothelial cell dysfunction was also confirmed in NTG patients,70 71 while population-based trials have demonstrated lower diastolic perfusion pressure, a measure of ocular blood flow, as a significant factor in the glaucoma incidence.5 17 19 However, objective evidence for underlying mechanisms have yet to be further clarified in the future.

Though these studies were limited by use of manual, subjective methods in measurement of retinal vessel diameters, their results were consistent with recent findings employing computer-assisted programs. De Leon et al investigated intereye differences in retinal vascular calibre in persons with asymmetrical glaucoma using the IVAN system.72 Once again, CRAE and CRVE were narrower for eyes with more severe disease. This relationship held after adjustment for age, gender, vascular risk factors and IOP, suggesting the difference in calibre to be due to severity discrepancy or other unknown factors, instead of systemic vascular diseases. Similarly, using the IVAN system, Yoo et al 73 analysed CRAE of glaucomatous suspects who showed unilateral glaucomatous conversion and noted narrower CRAE at baseline and at the point of glaucoma conversion. Angelica et al 74 dismissed the usage of retinal vessel calibre as a predictor in glaucoma in a hospital-based cross-sectional study, as no significant association could be drawn, though no explanation was given.

Population-based studies have further supported the above findings. The Blue Mountains Eye Study (BMES) showed that eyes with POAG were 2.7 times more likely to have generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing than eyes without glaucoma.75 This remained true after adjusting for risk factors for glaucoma and is independent of IOP and OPP. The Singapore Malay Eye Study found consistent association of quantitatively measured retinal vascular calibre with prevalence of glaucoma and larger vertical cup–disc ratio (CDR).76 The Beijing Eye Study showed significantly thinner retinal arteries but insignificant difference in retinal vein diameters.77 In the Handan Eye Study, both narrower retinal arterioles and venules were observed in primary angle closure glaucoma and POAG than those in normal controls, primary angle closure or primary angle closure suspect,78 suggesting that the narrowing of retinal vessels resulting from the glaucoma process is irrespective of status of angle closure. More recently, Yoo et al reported similar findings of retinal arteriolar narrowing in glaucoma, and further found that the diagnostic ability of retinal arteriolar calibre was comparable to retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness in detecting OAG, which is an optimistic introduction to its potential use in clinical settings.79

Nevertheless, the Beaver Dam Eye Study, a Caucasian population-based cohort study, did not find any associations of retinal vascular calibre related to prevalent glaucoma, large cup-to-disk ratio or elevated IOP.80 The authors attributed this deviation of their findings to the difference in the methodology of selection of arterioles for evaluation. A number of previous studies have focused solely on peripapillary vessel calibres62 74 however, Klein et al excluded peripapillary vessels because of the variability in retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in this area.

Overall, population-based and hospital-based cross-sectional studies largely supported the association of narrower vessel calibre with glaucoma, though individual studies focused on CRAE alone or only found significant reduction in CRAE and not CRVE.

Owing to the relatively new availability of technology in advanced geometry measurements, only two studies have evaluated retinal vascular geometric parameters other than calibre size. In a hospital-based study, Ciancaglini81 et al found correlation between ONH damage with a reduced retinal vascular fractal dimension. The Singapore Malay Eye Study also had a consistent finding of lower retinal vascular fractal dimension in glaucoma.82 In this study, Wu et al also evaluated vessel tortuosity and branching angle, and noted significantly smaller vessel tortuosity and retinal venular branching angle in eyes with glaucoma. Taken together, these findings suggest that circulatory optimality of vessels in glaucoma eyes may be compromised due to proven changes in the design of the geometrical pattern. However due to the cross-sectional nature of data, information on the temporality of retinal vascular changes with glaucoma incidence is limited.

Retinal vascular changes with glaucoma-associated outcomes

Reduced RNFL thickness, greater CDR and characteristic visual field defects are hallmarks of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Table 2 summarises cross-sectional studies that defined the relationship between retinal vascular parameters with these glaucoma-associated outcomes.

Table 2.

Relationship between retinal vascular parameters with glaucoma-associated outcomes

| Study and year | Study type | Sample size | Method of assessment | Outcome | Changes in parameters in association with glaucoma | ||||

| Arteriolar calibre | Venular calibre | Fractal dimension | Tortuosity | Branching angle | |||||

| Tham et al

87

(Singapore Malay Eye study) (2013) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 352 | SIVA | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | – |

| Kim et al 89 (2012) | Hospital-based, case-control study | Healthy: 48 NTG: 67 |

Visupac | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Not significant | – | – | – |

| Koh et al

98

(Singapore Malay Eye Study) (2010) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 2641 | SIVA | Neuroretinal rim area | – | – | – | Reduced | – |

| Zheng et al

65

(Singapore Malay Eye Study) (2009) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 2599 Any glaucoma: 107 |

IVAN | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Cheung et al

88

(Sydney Childhood Eye Study) (2008) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 1204 | Optimate | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Lim et al 90 (2009) | Hospital-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 104 | Optimate | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| CDR | Not significant | Reduced | – | – | – | ||||

| Samarawickrama et al

91

(Sydney Childhood Eye Study) (2003) |

Population-based, cross-sectional study | Healthy: 2038 | Optimate | RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| Hall et al

92

(2001) |

Hospital-based case series | POAG: 64 | Manual | VFD | Reduced | Not significant | – | – | – |

| Jonas and Naumann86 (1989) | Hospital-based, case-control study | Healthy: 173 POAG: 281 |

Manual | CDR | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – |

| RNFL thickness | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – | ||||

| VFD | Reduced | Reduced | – | – | – | ||||

CDR, cup–disc ratio; NTG, normal tension glaucoma; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; RNFL, retinal nerve fibre layer; VFD, visual field defect; SIVA, Singapore ‘I’ Vessel Assessment.

The correlation between narrower retinal vessel calibre and thinner RNFL thickness has been consistent since the 1980s.83–85 Studies analysed included hospital-based or population-based cross-sectional data, measurements carried out by manual means or computer programs, and populations of children, adolescents and adults. Although the biological mechanisms remain uncertain, these findings support the hypothesis that the loss of RGCs in thinned RNFL lowers metabolic and vascular demands, leading to narrower vascular calibre as part of an autoregulatory response.65 86–91 This is supported by a similar finding of decreased vessel diameter in non-glaucomatous optic neuropathies such as non-arteritic ischaemic optic neuropathy and descending optic nerve atrophy.63 Regardless, the temporal relationship of whether peripapillary vessel narrowing causes damage to the optic nerve, or the reverse, is true, has yet to be demonstrated definitively.

Discrepancy in the strength of association between arterioles and venules with RNFL was noted. The Singapore Malay Eye Study noted stronger association in venules than arterioles,65 87 92 while Kim et al 89 only associated RNFL thickness with arteriolar calibre, but not venular. The contrasting findings may be explained by the complex interaction between various mediators for vasodilatation and vasoconstriction on arterioles and venules. Retinal venular calibre is more strongly influenced by diabetes mellitus, while arteriolar calibre is more related to hypertension.89 It has also been proposed that narrower venular calibre may indicate venous congestion and cytotoxic damage, with subsequent secondary constriction of arteriole.93–96 The different spectrum of baseline systemic diseases in studies may therefore contribute to the discrepancy in findings. Nevertheless, compatible association between thinner RNFL thickness with narrowed calibre in healthy children and adolescents indicate that the relationship in adults with pathological eyes are at least in part physiological in origin.91

Apoptosis of RGCs lead to increased CDR, which is a pathognomonic feature of glaucoma. Studies have been inconsistent in demonstrating its relationship with vessel calibre.88 90 91 Lim et al 90 described the association between narrower retinal venular diameter with CDR, which was lacking for arteriolar calibre. This was attributed to retinal veins’ lower resistance to deformation due to their non-existent tunica media.90 Nevertheless, while increase in CDR is a clinical indicator for glaucoma progression, the reliability of CDR to detect glaucoma is limited by the wide variability in cup sizes, and interobserver and intraobserver variability. Poor correlation between RGC counts and CDR has also been demonstrated, suggesting that CDR is an insensitive method for evaluation of glaucomatous structural damage.97

Consistency is seen for the correlation between arteriole calibre with visual field defect. Hall et al compared calibre in POAG patients with marked difference in visual field defects between hemifields, and found significant correlation between arteriolar calibre with visual field defect.92 Similarly, Jonas and Naumann86 correlated visual field defects with both arteriole and venule calibres. Koh et al was the only study that evaluated vessel tortuosity and correlated decreased tortuosity with a thinner neuroretinal rim, which was more significant in arterioles.98 This was in line with studies that linked straighter retinal vessels with ischaemic heart disease and higher blood pressure99.

Longitudinal relationship between retinal vascular changes with glaucoma

Prospective studies provide information on the causative relationship between the parameters in question and glaucoma. This is relevant in determining whether vascular dysfunction preceded development of glaucoma or is a consequence of optic neuropathy progression. Table 3 lists longitudinal studies that evaluated the relationship between vascular geometry with the incidence or progression of glaucoma.

Table 3.

Relationship between vascular geometry with the incidence or progression of glaucoma

| Study and year | Study type | Follow-up duration | Sample size | Method of assessment | Outcome | Changes in parameters in association with glaucoma | |

| Arteriolar calibre | Venular calibre | ||||||

| Lee et al

102

(2014) |

Hospital-based, prospective study | 24.3 months | NTG: 27 | IVAN | Progression of glaucoma: 27 | Reduced | Not significant |

| Kawasaki et al

100

(The Blue Mountains Eye Study) (2013) |

Population-based, prospective study | 10 years | Total: 2417 | Optimate | Incidence of glaucoma: 82 | Reduced | Not significant |

| Ikram et al

101

(Rotterdam Eye Study) (2005) |

Population-based, prospective study | 6.5 years | Total: 3464 | Optimate | Incidence of glaucoma: 74 | Not significant | Not significant |

| Papastathopoulos & Jonas64

(1999) |

Hospital-based, prospective study | 37 months | OHT: 31 POAG: 59 NTG: 22 SOAG: 11 |

Colour stereo optic disc photographs | Progression of glaucoma: 37 | Reduced | – |

CRAE, central retinal artery equivalent; CRVE, central retinal vein equivalent; NTG, normal tension glaucoma; OHT, ocular hypertension; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; SOAG, secondary open-angle glaucoma; –, parameter not investigated.

Two studies evaluated glaucoma incidence. In an urban Caucasian population, 10-year follow-up data from the BMES revealed that narrower retinal arterioles were associated with higher OAG incidence, and suggest the potential use of retinal vessel calibre to identify patients with increased risk for glaucoma development.100 This finding supports previous cross-sectional studies’ concept that vascular changes are involved in the early course or pathogenesis of glaucoma. However, the Rotterdam Study, another Caucasian population-based study of 6.5 years of follow-up, had contradicting results.101 Both retinal arteriolar and venular baseline diameters were not found to be associated with incident OAG and incident optic disc changes. The discrepancy in findings may be due to the difference in duration of follow-up and higher incidence of POAG in BMES. Moreover, due to the elderly skewed cohort, the Rotterdam Study had a substantial number of participants (n=838) who passed away during the follow-up.

Progression of glaucoma was evaluated in two prospective studies. Papastathopoulos and Jonas performed a minimum 8-month follow-up for a group of patients with progressive glaucomatous optic nerve damage and noted significant focal narrowing of retinal arterioles associated with neuroretinal rim loss.64 This was not found in patients with static optic discs. Retinal venules were not analysed. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that focal narrowing does not necessarily involve progression of glaucoma, and is not pathognomonic for any particular subtype.

More recently, Lee et al compared 27 eyes with bilateral NTG who showed asymmetrical glaucoma progression after a mean follow-up of 24.3 months and found significant narrowing of retinal arteriolar calibre in progressed eyes but not in contralateral stable eyes.102 No correlation was found for retinal venular calibre, however, they hypothesised this may be due to clinically asymptomatic engorgement of venous blood flow in glaucoma, together with different regulatory mechanisms governing changes in retinal artery and vein diameters.102 No significant intereye difference was observed in the mean baseline vessel calibre between progressed and stable eyes.

Dynamic retinal vascular changes with glaucoma

The vascular theory of glaucoma considers optic nerve damage as a consequence of insufficient blood supply due to either increased IOP or other dysregulatory factors reducing ocular blood flow. Thus apart from associating structural vessel properties with glaucoma, functional performance reflects abnormalities and dysregulations in pathogenic eyes. Technological advancements have allowed quantitative evaluation of ocular blood flow and perfusion, and could serve as an imaging target for early diagnosis and monitoring of glaucoma.

ONH blood flow could be determined from simultaneous measurements of the blood column diameter and the centreline blood speed. Scanning laser Doppler flowmetry with automated perfusion imaging analysis evaluates frequency shift of perfused vessels and capillaries. Vessels are identified, segmented, and velocity then derived from the rate of flow shift. Laser speckle flowgraphy also calculates the speckle pattern that arises from the scatter of the laser irradiation from an illuminated fundus. Changes in the velocity of the blood flow blur the speckle pattern and the mean blur rate is then derived. Both methods have shown reduced ONH and peripapillary blood flow dynamics in glaucoma.103–105 Diminished flow in POAG suspect eyes before the development of clinically detectable visual field loss was confirmed as well.106 107 However, laser Doppler flowmetry only evaluates a small area of the retina, while absorbance and reflectance of disc tissue limits repeatability of laser speckle flowgraphy.

Ocular perfusion, another reflection of ocular blood flow, can be estimated by retinal arteriovenous passage time via digital scanning laser fluorescein angiograms. It characterises the passage of blood from the retinal artery, through capillaries, to the retinal vein. Prolonged passage time has been found to be reduced in both NTG and POAG patients,108–110 which was attributed to reduction of the capillary diameter potentially due to vasospasms or arteriosclerosis. Nevertheless, routine usage of fluorescein angiography (FA) is limited by its invasiveness, difficulty in accurate quantification and potential adverse systemic effects.

Limitations of the current studies and future directions

Despite the promising potential of retinal vascular imaging in glaucoma, there are still gaps in translating research into clinical practice. A shortcoming is the lack of knowledge about the normative data and reference levels for measurement. The majority of clinical trials compared pathological eyes with healthy eyes and derived conclusions based on comparison. Baseline reference values have yet to be concluded, which is further complicated by the influence of systemic, genetic and environmental factors on the variations of retinal vascular calibre size.111 Widespread implementation is also limited by availability of expertise. Current software is not fully automated and will require input from trained technicians to operate standardised protocols and provide expert manipulation and handling of specialised computer software. In addition, most studies in the current review did not specify subtypes in the associations, though the relationship between altered structural parameters with glaucoma held irrespective of IOP or angle closure. This may support the idea that vascular mechanisms underlie all subtypes of POAG. Further work could focus on elucidating differences in vessels in normal and high pressure glaucoma. Another limitation in the evaluation of retinal vascular calibre lies in its multifactorial influence by other systemic and individual characteristics. While most studies have taken into account patients’ age, gender, systemic vascular diseases and IOP, other variabilities, such as caffeine consumption and smoking habits, have not been considered.111 112 Hao et al reported significant changes in individual vessel calibre over a cardiac cycle but not in vessel calibre summaries (including CRAE and CRVE) and geometric measures, suggesting a mild correlation of pulse cycle and vessel diameter that need to be taken into account during sampling.113 In addition, although multiple advanced analytic tools enable quantification of retinal vascular imaging, there are technological challenges that may compromise precision. Refractive errors and axial length variabilities cause discrepancies in magnification, while image display quality (contrast, brightness and focus) may be compromised by media opacities and pupil size.23 The lack of automated imaging of retinal vascular also leads to unavoidable intragrader and intergrader variability that has yet to be refined.114

Future directions include focused analysis of the chronological nature of retinal vessel changes via means of longitudinal studies so as to better delineate the chicken–egg relationship between glaucomatous changes and narrowed vessel calibre. Detailed subtype analysis is also warranted to delineate whether the vascular phenomenon is more profound in NTG eyes, as conventionally believed, or actually exists as a spectrum among all glaucoma subtypes. Effort in clinical application of current data and ease of software use in daily practice should also be explored to close the gap between clinical and experimental investigations.

New advances in retinal imaging

Advances in technology have attempted to supplement the shortcomings of existing instruments. Peripapillary capillaries have been recognised to be a highly specialised vasculature that supply the nerve fibre layer,115 and a better understanding of this network may reflect focal or contiguous disc capillary network defects or act as a supplementary indicator of RGC damage.

FA is the gold standard for imaging the capillary network. However, it is invasive in operation (requiring intravenous injection of fluorescein dye), time consuming, confounded by superimposition of capillaries from different retinal layers and only offers two-dimensional image analysis with lack of quantifiable parameters. All of the shortages above reduce the clinical utility of FA. Optical coherence tomography—angiography (OCT-A) offers three-dimensional, non-invasive retinal and choroidal microcirculation vasculature analysis and blood flow estimation116 117 (figure 2). It is based on mapping erythrocyte movement over time by comparing sequential optical coherence tomography-B scan (OCT-B scan) ultrasounds images at a given cross-section. OCT-A is able to separately detect the superficial capillary network in the ganglion cell layer, the deep capillary network in the outer plexiform layer and choriocapillaris below retinal pigment epithelium without intravenous dye injection, providing depth-resolved visualisation of the retinal and choroid vasculature and blood flow. Moreover, OCT-A can generate data on vascular flow to quantify retinal or optic disc perfusion, independent of time and dye injection. As OCT-angiograms are coregistered with OCT-B scans from the same area, it also allows for simultaneous visualisation of structure and blood flow for clinical interpretation. Recently, data derived from OCT-A readings have shown that peripapillary vessel density, peripapillary flow index and optic disc perfusion are reduced in glaucomatous eyes compared with aged-matched normal eyes.118–122 These changes correlated to disease severity, structural changes and functional damages, including RNFL thickness, visual field mean deviation, visual field pattern SD and visual field index. In addition, OCT-A indices have outperformed RNFL thickness in having a stronger correlation with visual field loss.117 118 123 These findings support the notion that OCT-A is a promising and useful imaging modality for evaluating glaucomatous microvasculopathy, which may allow earlier diagnosis and detection of nerve fibre functional loss before thinning occurs. Compared with FA, OCT-A also offers superior details in analysing radial peripapillary capillaries, which is a unique plexus within the inner nerve RNFL that provides nutritional support to the RGCs.124 Reduction in the network’s density has been strongly correlated with thinner RNFL thickness and poorer visual field index.125 Compared with vessel measurements based on digital photography, which is more appropriate for large vessels with less sensitivity, studies that utilised OCT-A allowed more accurate measurement of the low velocities of deep plexuses. Furthermore, since OCT-A is a depth-resolved technique, it offers technical advantage in the growing interest of investigating the deep layer microvasculature. Recently, with OCT-A imaging, Suh et al 126 reported that decreased deep-layer vessel density within the parapapillary area, which is downstream from the SPCA perfused deep ONH, is associated with lamina cribrosa defect, visual field impairment and RNFL thinning. This finding may support the microvascular pathophysiology concepts of glaucoma, since the superficial and deep retinal layers are perfused individually by the central retinal and short posterior ciliary arteries, respectively.127 However, OCT-A has several limitations. First, limited by the current scanning speed and patient comfort during the acquisition, a 6×6 mm2 area is the largest scanning field that can be provided by the most updated OCT-A imaging device. This may be suboptimal for peripheral retinal vasculature. Second, data on validity of OCT-A assessment, such as intersection or intrasection reliability, comparability with gold standard and correlation with clinical outcomes is still scarce. Third, despite modern technology, automated, objective and robust methods that have evidence-based proof of accuracy for vasculature identification for quantitative assessment of capillary perfusion are still lacking.128 129 In addition, image artefacts are common in OCT-A, especially motion and projection artefacts, leading to inaccurate assessment.130 Advanced softwares to neutralise artefacts while maintaining adequate intensity and visibility of pathological vascular changes are required,125 while media opacities and segmentation errors should be taken into account as factors that influence OCT-A interpretation.

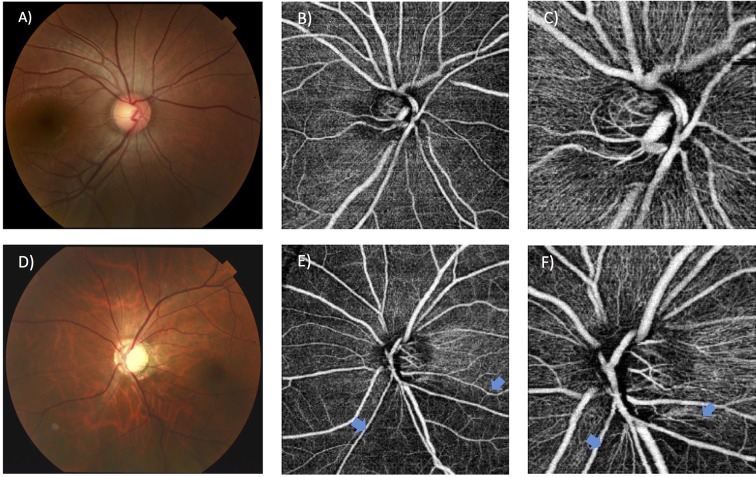

Figure 2.

Assessment of retinal capillary network around optic nerve head using optical coherence tomography angiography in a normal eye (A–C) and a glaucomatous eye (D–F). Decreased peripapillary capillary density is indicated by blue arrows.

Retinal functional imaging is another method to obtain blood flow velocity by comparing erythrocyte movement in serial retinal images. Elevated mean retinal blood flow velocity was found in peripapillary vasculature,131 which may reflect a steal phenomenon when retinal vessels experience increased flow following decreased retinal capillary perfusion. Increased venous velocity has been consistently found in eyes with preperimetric glaucomatous optic neuropathy, which may reflect early vascular dysfunction.132 Imaging systems that employ adaptive optics, such as retinal fundus camera, OCT and scanning laser ophthalmoscope, have also provided in-vivo, high-resolution imaging of the vasculature and nerve fibre layer that overcomes poor lateral resolution in conventional ocular optics,133 and have been shown to be in precise agreement with histology in primate studies.134

Conclusion

This review offers solid, consistent evidence for proof of concept that structural designs and changes in the retinal vasculature are associated with glaucoma. Most cross-sectional studies support the association between narrowed vessel calibre with glaucoma and glaucoma-associated outcomes, including thinner RNFL, increased CDR and thinner neuroretinal rim area. Specific vessel patterns, including reduced fractal dimension, tortuosity and branching angle, have also been largely associated with glaucoma in hospital-based and population-based studies, though evidence is scarce. Further meta-analysis or pooled analysis could quantitatively evaluate their consistency. Longitudinal data bear weight in elucidating the temporal association of these findings with the incidence or progression of glaucoma. However, the small number of related studies limits the significance of the evidence, particularly when conclusions are in contradiction. More prospective, long-term follow-up data are needed.

New retinal imaging techniques confirm the pathogenetic concept of vascular dysregulation in glaucoma eyes, especially with NTG. Clear differences when compared with controls are demonstrated. Their potential usefulness in the diagnosis, staging and monitoring of glaucoma is recognised, and their function as a future imaging target should be utilised.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed substantial information or material in this submission for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. . The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:701–13. discussion 829–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satilmis M, Orgül S, Doubler B, et al. . Rate of progression of glaucoma correlates with retrobulbar circulation and intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:664–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(02)02156-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein BE, Klein R, Sponsel WE, et al. . Prevalence of glaucoma. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta N, Weinreb RN. New definitions of glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1997;8:38–41. doi:10.1097/00055735-199704000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tielsch JM, Katz J, Singh K, et al. . A population-based evaluation of glaucoma screening: the Baltimore Eye Survey. Am J Epidemiol 1991;134:1102–10. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flammer J, Autoregulation MM. A balancing act between supply and demand. Can J Ophthalmol 2008;43:317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galassi F, Giambene B, Varriale R. Systemic vascular dysregulation and retrobulbar hemodynamics in normal-tension glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:4467–71. doi:10.1167/iovs.10-6710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tielsch JM, Katz J, Sommer A, et al. . Hypertension, perfusion pressure, and primary open-angle glaucoma. A population-based assessment. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:216–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitchell P, Smith W, Chey T, et al. . Open-angle glaucoma and diabetes: the Blue Mountains Eye Study, Australia. Ophthalmology 1997;104:712–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Smith W. Is there an association between migraine headache and open-angle glaucoma? Findings from the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1714–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leske MC, Connell AM, Wu SY, et al. . Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma. The Barbados Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol 1995;113:918–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tielsch JM, Katz J, Quigley HA, et al. . Diabetes, intraocular pressure, and primary open-angle glaucoma in the Baltimore Eye Survey. Ophthalmology 1995;102:48–53. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(95)31055-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flammer J, Konieczka K, Flammer AJ. The primary vascular dysregulation syndrome: implications for eye diseases. EPMA J 2013;4:14 doi:10.1186/1878-5085-4-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mojon DS, Hess CW, Goldblum D, et al. . Normal-tension glaucoma is associated with sleep apnea syndrome. Ophthalmologica 2002;216:180–4. doi:10.1159/000059625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leung D, Chan P, Tham C, et al. . Normal tension glaucoma: risk factors pertaining to a sick eye in a sick body. Hong Kong J Ophthalmol 2007;13:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gherghel D, Orgül S, Gugleta K, et al. . Relationship between ocular perfusion pressure and retrobulbar blood flow in patients with glaucoma with progressive damage. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130:597–605. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00766-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leske MC, Wu SY, Nemesure B, et al. . Incident open-angle glaucoma and blood pressure. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:954–9. doi:10.1001/archopht.120.7.954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, et al. ; BESs Study Group. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology 2008;115:85–93. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. . Vascular risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma: the Egna-Neumarkt study. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1287–93. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00138-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, et al. . The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of hispanic subjects: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1819–26. doi:10.1001/archopht.119.12.1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leske MC, Heijl A, Hyman L, et al. ; EMGT Group. Predictors of long-term progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Ophthalmology 2007;114:1965–72. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Costa VP, Harris A, Anderson D, et al. . Ocular perfusion pressure in glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92:e252–e266. doi:10.1111/aos.12298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheung CY, Ikram MK, Sabanayagam C, et al. . Retinal microvasculature as a model to study the manifestations of hypertension. Hypertension 2012;60:1094–103. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheung CY, Zheng Y, Hsu W, et al. . Retinal vascular tortuosity, blood pressure, and cardiovascular risk factors. Ophthalmology 2011;118:812–8. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheung CY, Tay WT, Mitchell P, et al. . Quantitative and qualitative retinal microvascular characteristics and blood pressure. J Hypertens 2011;29:1380–91. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328347266c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sasongko MB, Wong TY, Nguyen TT, et al. . Retinal vascular tortuosity in persons with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 2011;54:2409–16. doi:10.1007/s00125-011-2200-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benitez-Aguirre P, Craig ME, Sasongko MB, et al. . Retinal vascular geometry predicts incident retinopathy in young people with type 1 diabetes: a prospective cohort study from adolescence. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1622–7. doi:10.2337/dc10-2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yau JW, Kawasaki R, Islam FM, et al. . Retinal fractal dimension is increased in persons with diabetes but not impaired glucose metabolism: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) study. Diabetologia 2010;53:2042–5. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1811-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grauslund J, Green A, Kawasaki R, et al. . Retinal vascular fractals and microvascular and macrovascular complications in type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmology 2010;117:1400–5. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheung N, Donaghue KC, Liew G, et al. . Quantitative assessment of early diabetic retinopathy using fractal analysis. Diabetes Care 2009;32:106–10. doi:10.2337/dc08-1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheung CY, Lamoureux E, Ikram MK, et al. . Retinal vascular geometry in Asian persons with diabetes and retinopathy. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012;6:595–605. doi:10.1177/193229681200600315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheung CY-l, Tay WT, Ikram MK, et al. . Retinal microvascular changes and risk of stroke: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Stroke 2013;44:2402–8. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ong Y-T, De Silva DA, Cheung CY, et al. . Microvascular structure and network in the retina of patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2013;44:2121–7. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guthauser U, Flammer J, Mahler F. The relationship between digital and ocular vasospasm. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1988;226:224–6. doi:10.1007/BF02181185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harris A, Sergott RC, Spaeth GL, et al. . Color Doppler analysis of ocular vessel blood velocity in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118:642–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)76579-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mroczkowska S, Benavente-Perez A, Negi A, et al. . Primary open-angle glaucoma vs normal-tension glaucoma: the vascular perspective. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131:36–43. doi:10.1001/2013.jamaophthalmol.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Flammer J, Orgül S, Costa VP, et al. . The impact of ocular blood flow in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2002;21:359–93. doi:10.1016/S1350-9462(02)00008-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flammer J, Orgül S. Optic nerve blood-flow abnormalities in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 1998;17:267–89. doi:10.1016/S1350-9462(97)00006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Golzan SM, Avolio A, Magnussen J, et al. . Visualization of orbital flow by means of phase contrast MRI. 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 3384–7. 2012. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1109/embc.2012.6346691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grunwald JE, Sinclair SH, Riva CE. Autoregulation of the retinal circulation in response to decrease of intraocular pressure below normal. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1982;23:124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolf S, Arend O, Sponsel WE, et al. . Retinal hemodynamics using scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and hemorheology in chronic open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1993;100:1561–6. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(93)31444-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Michelson G, Langhans MJ, Groh MJM. Perfusion of the juxtapapillary retina and the neuroretinal rim area in primary open angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 1996;5:91–8. doi:10.1097/00061198-199604000-00003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harju M, Vesti E. Blood flow of the optic nerve head and peripapillary retina in exfoliation syndrome with unilateral Glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001;239:271–7. doi:10.1007/s004170100269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yin ZQ, Vaegan , Millar TJ, et al. . Widespread choroidal insufficiency in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 1997;6:23–32. doi:10.1097/00061198-199702000-00006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murray CD. The physiological principle of minimum work: I. The vascular system and the cost of blood volume. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1926;12:207–14. doi:10.1073/pnas.12.3.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sherman TF. On connecting large vessels to small. The meaning of Murray's law. J Gen Physiol 1981;78:431–53. doi:10.1085/jgp.78.4.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong TY, Knudtson MD, Klein R, et al. . Computer-assisted measurement of retinal vessel diameters in the Beaver Dam Eye Study: methodology, correlation between eyes, and effect of refractive errors. Ophthalmology 2004;111:1183–90. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hubbard LD, Brothers RJ, King WN, et al. . Methods for evaluation of retinal microvascular abnormalities associated with hypertension/sclerosis in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ophthalmology 1999;106:2269–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Perez-Rovira A, MacGillivray T, Trucco E, et al. . VAMPIRE: vessel assessment and measurement platform for images of the REtina. 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 3391–4. 2011. [Epub ahead of print] doi:10.1109/iembs.2011.6090918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Struijker-Boudier HA, Heijnen BF, Liu YP, et al. . Phenotyping the microcirculation. Hypertension 2012;60:523–7. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.188482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lehmann MV, Schmieder RE. Remodeling of retinal small arteries in hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2011;24:1267–73. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khavandi K, Arunakirinathan M, Greenstein AS, et al. . Retinal arterial hypertrophy: the new LVH? Curr Hypertens Rep 2013;15:244–52. doi:10.1007/s11906-013-0347-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McGeechan K, Liew G, Macaskill P, et al. . Prediction of incident stroke events based on retinal vessel caliber: a systematic review and individual-participant meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:1323–32. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McGeechan K, et al. . Meta-analysis: retinal vessel caliber and risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:404–13. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-6-200909150-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Patton N, Aslam TM, MacGillivray T, et al. . Retinal image analysis: concepts, applications and potential. Prog Retin Eye Res 2006;25:99–127. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hart WE, Goldbaum M, Côté B, et al. . Measurement and classification of retinal vascular tortuosity. Int J Med Inform 1999;53(2-3):239–52. doi:10.1016/S1386-5056(98)00163-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zamir M, Medeiros JA, Cunningham TK. Arterial bifurcations in the human retina. J Gen Physiol 1979;74:537–48. doi:10.1085/jgp.74.4.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liew G, Wang JJ, Cheung N, et al. . The retinal vasculature as a fractal: methodology, reliability, and relationship to blood pressure. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1951–6. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mainster MA. The fractal properties of retinal vessels: embryological and clinical implications. Eye 1990;4:235–41. doi:10.1038/eye.1990.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jonas JB, Nguyen XN, Naumann GO. Parapapillary retinal vessel diameter in normal and glaucoma eyes. I. Morphometric data. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989;30:1599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rader J, Feuer WJ, Anderson DR. Peripapillary vasoconstriction in the glaucomas and the anterior ischemic optic neuropathies. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;117:72–80. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)73017-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rankin SJA, Drance SM. Peripapillary focal retinal arteriolar narrowing in open angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 1996;5:22–8. doi:10.1097/00061198-199602000-00005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Frisen L, Claesson M. Narrowing of the retinal arterioles in descending optic atrophy. A quantitative clinical study. Ophthalmology 1984;91:1342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Papastathopoulos KI, Jonas JB. Follow up of focal narrowing of retinal arterioles in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:285–9. doi:10.1136/bjo.83.3.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zheng Y, Cheung N, Aung T, et al. . Relationship of retinal vascular caliber with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:4091–6. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saccà SC, Pascotto A, Camicione P, et al. . Oxidative DNA damage in the human trabecular meshwork: clinical correlation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:458–63. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.4.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sorkhabi R, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Javadzadeh A, et al. . Oxidative DNA damage and total antioxidant status in glaucoma patients. Mol Vis 2011;17:41–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zeitz O, Wagenfeld L, Wirtz N, et al. . Influence of oxygen free radicals on the tone of ciliary arteries: a model of vasospasms of ocular vasculature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;245:1327–33. doi:10.1007/s00417-006-0526-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zeitz O, Galambos P, Wagenfeld L, et al. . Glaucoma progression is associated with decreased blood flow velocities in the short posterior ciliary artery. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:1245–8. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.093633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Buckley C, Hadoke PW, Henry E, et al. . Systemic vascular endothelial cell dysfunction in normal pressure glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:227–32. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.2.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Henry E, Newby DE, Webb DJ, et al. . Altered endothelin-1 vasoreactivity in patients with untreated normal-pressure glaucoma. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2006;47:2528–32. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. De Leon JM, Cheung CY, Wong TY, et al. . Retinal vascular caliber between eyes with asymmetric glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015;253:583–9. doi:10.1007/s00417-014-2895-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yoo E, Yoo C, Lee TE, et al. . Retinal vessel diameter in bilateral glaucoma suspects: comparison between the eye converted to glaucoma and the contralateral non-converted eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016;254:1599–608. doi:10.1007/s00417-016-3392-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Angelica MM, Sanseau A, Argento C. Arterial narrowing as a predictive factor in glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol 2001;23:271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mitchell P, Leung H, Wang JJ, et al. . Retinal vessel diameter and open-angle glaucoma: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2005;112:245–50. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Amerasinghe N, Aung T, Cheung N, et al. . Evidence of retinal vascular narrowing in glaucomatous eyes in an Asian population. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:5397–402. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang S, Xu L, Wang Y, et al. . Retinal vessel diameter in normal and glaucomatous eyes: the Beijing Eye Study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007;35:800–7. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01627.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gao J, Liang Y, Wang F, et al. . Retinal vessels change in primary angle-closure glaucoma: the Handan Eye Study. Sci Rep 2015;5:9585 doi:10.1038/srep09585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yoo E, Yoo C, Lee B-ram, et al. . Diagnostic ability of retinal vessel diameter measurements in open-angle glaucoma. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:7915–22. doi:10.1167/iovs.15-18087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, et al. . The relation of retinal microvascular characteristics to age-related eye disease: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:435–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ciancaglini M, Guerra G, Agnifili L, et al. . Fractal dimension as a new tool to analyze optic nerve head vasculature in primary open angle glaucoma. In vivo 2015;29:273–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wu R, Cheung CY, Saw SM, et al. . Retinal vascular geometry and glaucoma: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:77–83. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Araie M. Pattern of visual field defects in normal-tension and high-tension glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 1995;6:36–45. doi:10.1097/00055735-199504000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Bowd C, Zangwill LM, Berry CC, et al. . Detecting early glaucoma by assessment of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001;42:1993–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Garway-Heath DF, Ruben ST, Viswanathan A, et al. . Vertical cup/disc ratio in relation to optic disc size: its value in the assessment of the glaucoma suspect. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:1118–24. doi:10.1136/bjo.82.10.1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jonas JB, Naumann GO. Parapapillary retinal vessel diameter in normal and glaucoma eyes. II. Correlations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989;30:1604–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tham YC, Cheng CY, Zheng Y, et al. . Relationship between retinal vascular geometry with retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer in nonglaucomatous eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:7309–16. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cheung N, Huynh S, Wang JJ, et al. . Relationships of retinal vessel diameters with optic disc, macular and retinal nerve fiber layer parameters in 6-year-old children. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:2403–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.07-1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kim JM, Sae Kim M, Ju Jang H, et al. . The association between retinal vessel diameter and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in asymmetric normal tension glaucoma patients. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:5609–14. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-9783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lim LS, Saw SM, Cheung N, et al. . Relationship of retinal vascular caliber with optic disc and macular structure. Am J Ophthalmol 2009;148:368–75. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Samarawickrama C, Huynh SC, Wang JJ, et al. . Relationship between retinal structures and retinal vessel caliber in normal adolescents. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2009;50:5619–24. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-3878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hall JK, Andrews AP, Walker R, et al. . Association of retinal vessel caliber and visual field defects in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:855–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01200-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Witt N, Wong TY, Hughes AD, et al. . Abnormalities of retinal microvascular structure and risk of mortality from ischemic heart disease and stroke. Hypertension 2006;47:975–81. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000216717.72048.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wong TY, Klein R, Couper DJ, et al. . Retinal microvascular abnormalities and incident stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. The Lancet 2001;358:1134–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06253-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. . Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. JAMA 2002;287:1153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wong TY, Klein R, Sharrett AR, et al. ; ARIC Investigators. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of diabetes mellitus in middle-aged persons. Jama 2002;287:2528–33. doi:10.1001/jama.287.19.2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Tatham AJ, Weinreb RN, Zangwill LM, et al. . The relationship between cup-to-disc ratio and estimated number of retinal ganglion cells. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:3205–14. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-11467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Koh V, Cheung CY, Zheng Y, et al. . Relationship of retinal vascular tortuosity with the neuroretinal rim: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51:3736–41. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-5008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Taarnhøj NC, Munch IC, Sander B, et al. . Straight versus tortuous retinal arteries in relation to blood pressure and genetics. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:1055–60. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.134593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kawasaki R, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, et al. . Retinal vessel caliber is associated with the 10-year incidence of glaucoma: the blue mountains eye study. Ophthalmology 2013;120:84–90. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ikram MK, de Voogd S, Wolfs RC, et al. . Retinal vessel diameters and incident open-angle glaucoma and optic disc changes: the Rotterdam study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:1182–7. doi:10.1167/iovs.04-1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Lee TE, Kim YY, Yoo C. Retinal vessel diameter in normal-tension glaucoma patients with asymmetric progression. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;252:1795–801. doi:10.1007/s00417-014-2756-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yokoyama Y, Aizawa N, Chiba N, et al. . Significant correlations between optic nerve head microcirculation and visual field defects and nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma patients with myopic glaucomatous disk. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:1721–7. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S23204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tobe LA, Harris A, Hussain RM, et al. . The role of retrobulbar and retinal circulation on optic nerve head and retinal nerve fibre layer structure in patients with open-angle glaucoma over an 18-month period. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:609–12. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Piltz-Seymour JR. Laser Doppler flowmetry of the optic nerve head in glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;43(Suppl 1):S191–S198. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(99)00053-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Michelson G, Langhans MJ, Harazny J, et al. . Visual field defect and perfusion of the juxtapapillary retina and the neuroretinal rim area in primary open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1998;236:80–5. doi:10.1007/s004170050046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Piltz-seymour JR, Grunwald JE, Hariprasad SM, et al. . Optic nerve blood flow is diminished in eyes of primary open-angle glaucoma suspects. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;132:63–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)00871-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Arend O, Remky A, Plange N, et al. . Capillary density and retinal diameter measurements and their impact on altered retinal circulation in glaucoma: a digital fluorescein angiographic study. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:429–33. doi:10.1136/bjo.86.4.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Huber K, Plange N, Remky A, et al. . Comparison of colour Doppler imaging and retinal scanning laser fluorescein angiography in healthy volunteers and normal pressure glaucoma patients. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2004;82:426–31. doi:10.1111/j.1395-3907.2004.00269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Plange N, Kaup M, Remky A, et al. . Prolonged retinal arteriovenous passage time is correlated to ocular perfusion pressure in normal tension glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;246:1147–52. doi:10.1007/s00417-008-0807-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Sun C, Wang JJ, Mackey DA, et al. . Retinal vascular caliber: systemic, environmental, and genetic associations. Surv Ophthalmol 2009;54:74–95. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Knudtson MD, Klein BE, Klein R, et al. . Variation associated with measurement of retinal vessel diameters at different points in the pulse cycle. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:57–61. doi:10.1136/bjo.88.1.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hao H, Sasongko MB, Wong TY, et al. . Does retinal vascular geometry vary with cardiac cycle? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:5799–805. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-9326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Hubbard LD, et al. . Revised formulas for summarizing retinal vessel diameters. Curr Eye Res 2003;27:143–9. doi:10.1076/ceyr.27.3.143.16049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Alterman M, Henkind P. Radial peripapillary capillaries of the retina. II. Possible role in Bjerrum scotoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1968;52:26–31. doi:10.1136/bjo.52.1.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Spaide RF, Klancnik JM, Cooney MJ. Retinal vascular layers imaged by fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography angiography. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:45–50. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Jia Y, Wei E, Wang X, et al. . Optical coherence tomography angiography of optic disc perfusion in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1322–32. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Liu L, Jia Y, Takusagawa HL, et al. . Optical coherence tomography angiography of the peripapillary retina in glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:1045–52. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Lévêque P-M, Zéboulon P, Brasnu E, et al. . Optic disc vascularization in glaucoma: value of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography angiography. J Ophthalmol 2016;2016:1–9. doi:10.1155/2016/6956717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Chen CL, Bojikian KD, Gupta D, et al. . Optic nerve head perfusion in normal eyes and eyes with glaucoma using optical coherence tomography-based microangiography. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2016;6:125–33. doi:10.21037/qims.2016.03.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Akagi T, Iida Y, Nakanishi H, et al. . Microvascular density in glaucomatous eyes with hemifield visual field defects: an optical coherence tomography angiography study. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;168:237–49. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Bojikian KD, Chen CL, Wen JC, et al. . Optic disc perfusion in primary open angle and normal tension glaucoma eyes using optical coherence tomography-based microangiography. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154691 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Nilforushan N, Nassiri N, Moghimi S, et al. . Structure-function relationships between spectral-domain OCT and standard achromatic perimetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53:2740–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Yu PK, Cringle SJ, Yu DY. Correlation between the radial peripapillary capillaries and the retinal nerve fibre layer in the normal human retina. Exp Eye Res 2014;129:83–92. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2014.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Mammo Z, Heisler M, Balaratnasingam C, et al. . Quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography of radial peripapillary capillaries in glaucoma, glaucoma suspect, and normal eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;170:41–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Suh MH, Zangwill LM, Manalastas PI, et al. . Deep retinal layer microvasculature dropout detected by the optical coherence tomography angiography in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2016;123:2509–18. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Onda E, Cioffi GA, Bacon DR, et al. . Microvasculature of the human optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;120:92–102. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)73763-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Kim AY, Chu Z, Shahidzadeh A, et al. . Quantifying microvascular density and morphology in diabetic retinopathy using Spectral-Domain optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:OCT362–70. doi:10.1167/iovs.15-18904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Hwang TS, Gao SS, Liu L, et al. . Automated quantification of capillary nonperfusion using optical coherence tomography angiography in diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:367–73. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.5658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Spaide RF, Fujimoto JG, Waheed NK. Image artifacts in optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina 2015;35:2163–80. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Jangi AA, Spielberg L, Landa G, et al. . Peripapillary blood flow velocity in glaucoma evaluated by the retinal functional imager (RFI). Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2010;51:2692–92. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Burgansky-Eliash Z, Bartov E, Barak A, et al. . Blood-Flow velocity in glaucoma patients measured with the retinal function imager. Curr Eye Res 2016;41:965–70. doi:10.3109/02713683.2015.1080278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Hasegawa T, Ooto S, Takayama K, et al. . Cone integrity in glaucoma: an adaptive-optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy study. Am J Ophthalmol 2016;171:53–66. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2016.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Scoles D, Gray DC, Hunter JJ, et al. . In-vivo imaging of retinal nerve fiber layer vasculature: imaging histology comparison. BMC Ophthalmol 2009;9:9 doi:10.1186/1471-2415-9-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]