Abstract

Background

ECG left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a well‐known predictor of cardiovascular disease. However, no prior study has characterized patterns of presence/absence of ECG LVH (“ECG LVH trajectories”) across the adult lifespan in both sexes and across ethnicities. We examined: (1) correlates of ECG LVH trajectories; (2) the association of ECG LVH trajectories with incident coronary heart disease, transient ischemic attack, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and heart failure; and (3) reclassification of cardiovascular disease risk using ECG LVH trajectories.

Methods and Results

We performed a cohort study among 75 412 men and 107 954 women in the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program who had available longitudinal exposures of ECG LVH and covariates, followed for a median of 4.8 (range <1–9.3) years. ECG LVH was measured by Cornell voltage‐duration product. Adverse trajectories of ECG LVH (persistent, new development, or variable pattern) were more common among blacks and Native American men and were independently related to incident cardiovascular disease with hazard ratios ranging from 1.2 for ECG LVH variable pattern and transient ischemic attack in women to 2.8 for persistent ECG LVH and heart failure in men. ECG LVH trajectories reclassified 4% and 7% of men and women with intermediate coronary heart disease risk, respectively.

Conclusions

ECG LVH trajectories were significant indicators of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure risk, independently of level and change in cardiovascular disease risk factors, and may have clinical utility.

Keywords: cohort study, Cornell voltage product, electrocardiography, left ventricular hypertrophy

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Primary Prevention, Quality and Outcomes

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the largest study to investigate the predictive value of ECG‐derived trajectories of left ventricular hypertrophy for coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure. The study includes both sexes and all ethnic groups in the United States.

The results demonstrate clear ethnic disparities in trajectories of left ventricular hypertrophy and independent predictive value of left ventricular hypertrophy trajectories for incident coronary heart disease, stroke types, and heart failure in both men and women.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Consideration of left ventricular hypertrophy trajectories may help improve cardiovascular disease risk assessment and understanding of sources of ethnic disparities in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Introduction

ECG left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) affects 1% to 5% of the population, about one third of patients with hypertension,1, 2, 3, 4 and is more prevalent among blacks.3, 5, 6 Findings from prior studies have demonstrated that baseline and serial changes in ECG LVH independently predict subsequent cardiovascular events,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 despite having low sensitivity compared with echocardiographically derived LVH.4, 13, 14, 15 However, there has been no single study that has examined trajectories of ECG LVH across the adult lifespan, in both sexes, and including all major ethnic groups. Thus, the aims of this study were: first, to map the trajectories of ECG LVH and its clinical correlates in an ethnically diverse sample of patients older than 30 years, and, second, to ascertain the association of ECG LVH trajectories with incident coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke types (transient ischemic attack, ischemic, hemorrhagic), and heart failure (HF), as well as its incremental clinical utility in terms of cardiovascular risk prediction.

Methods

Study Population and Cohort Study Design

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC) is an integrated healthcare delivery system that serves over 3.8 million members. KPNC's population is ethnically and socioeconomically diverse and is broadly representative of the Northern California population.16

For the analysis presented here, we leveraged an existing database containing 6 547 785 12‐lead surface ECGs performed in 1 772 813 KPNC members as part of routine outpatient or inpatient care between January 1, 1995, and June 30, 2008 (median of 4 ECGs per person). The following initial exclusions were applied to all of the ECGs in the database (these conditions were nonmutually exclusive): age younger than 30 years (n=231 067), pace rhythm (n=6681), Wolff‐Parkinson‐White syndrome (n=338), heart rate >130 beats per minute (n=18 034), right or left bundle branch block (n=52 545), and ventricular premature contractions/bigeminy pattern (n=39 274), resulting in a final cohort of 1 240 662 persons. An index ECG database was created by selecting one ECG at random (for those with only 1 ECG, that one ECG was the index ECG). To create the longitudinal LVH cohort, we further excluded those with only 1 ECG or those with 2 ECGs and whose second ECG was less than 6 months after the index ECG, resulting in a cohort of 538 621 persons. Of those, 125 404 were excluded for being in the no‐contact file (Kaiser members who had stated that they did not want to be in or contribute data to research studies); 18 009 for disenrollment for more than 2 consecutive years after the index ECG; 191 825 for not having serial measures of body mass index, blood pressure, or serum lipids (total cholesterol and high‐density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol); and 38 768 for having prevalent cardiovascular disease (CVD; primary discharge diagnosis of any of the 5 conditions of interest between the last ECG and going back 5 years from the index ECG), yielding a final analytical sample of 183 366 persons (75 412 men and 107 954 women). The final analytical cohort was older than the 1.2 million index ECG cohort (58 versus 56 years) and had a larger representation of women (59% versus 53%) but was similar in terms of race/ethnic distribution.

Serial LVH Measurements

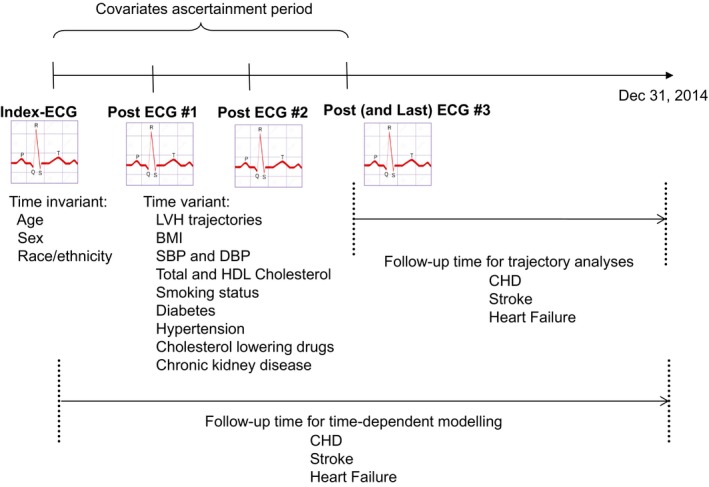

All 12‐lead surface ECGs were obtained using cardiographs manufactured by Philips Medical Systems. We derived, for each individual ECG, the Cornell product as (RaVL+Sv3+6 mm in women)×QRS duration (ms) using CalECG versus 3 software. LVH was defined as Cornell product ≥2440 mm×ms.17, 18, 19 For each cohort member with 2 or more ECGs, we selected ECGs at least 6 months apart starting at the index ECG. No ECGs before the index ECG were used because of greater likelihood of missing data on covariates of interest, particularly blood pressure. The Figure depicts a theoretical scenario of a patient with 3 serial ECGS after the index ECG. Finally, we incorporated information from serial Cornell product measurements to create 5 a priori–defined mutually exclusive ECG LVH trajectories: (1) persistent absence of LVH; (2) persistent LVH; (3) new development of LVH (no LVH at baseline followed by persistent LVH thereafter. If we denote 0 as no LVH and 1 as LVH, new development was defined as a string of 0s of any length, followed by a 1, and no 0s thereafter, eg, 001, 011, 000011, and 0000011); (4) regression of LVH (LVH at baseline followed by no LVH thereafter); and (5) variable patterns (people who did not fit any of the other 4 criteria). Evidence of either persistent, new development, regression, or variable pattern were grouped as “any LVH.”

Figure 1.

Schematic of study design. BMI indicates body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Baseline, Serial Covariates, and Cardiovascular End Points

Date of birth, sex, and race/ethnicity were ascertained from the patient's demographics file. For each person in the cohort, the covariate ascertainment period was the time between the index and the last ECG. For time‐variant continuous covariates (body mass index [weight in kg divided by height in meters squared], systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and estimated glomerular filtration rate), we pulled data from health plan outpatient databases for repeated measures separated by at least 6 months. Smoking status was obtained from our database of outpatient visits and was defined as current, past, never, new starter in the covariate ascertainment period, quitter in the covariate ascertainment period, or missing. Diabetes mellitus status was obtained by cross linkage with the Kaiser Division of Research Diabetes Registry and was defined as “yes” if a diagnosis was present at any time during the covariate ascertainment period and “no” otherwise. Hypertension was ascertained by combining outpatient diagnostic codes and prescription of antihypertensive agents at any time during the covariate ascertainment period, and hyperlipidemia was ascertained by using outpatient prescriptions for cholesterol‐lowering drugs also at any time during the covariate ascertainment period. In KPNC, typical practice includes blood pressure measurements with the patient in a sitting position by automated sphygmomanometers operated by trained medical assistants, with repeat measurements performed as needed by physicians using aneroid sphygmomanometers.20 The validity of our hypertension diagnostic codes has been reported before.20 Glomerular filtration rate was calculated using creatinine levels extracted from the laboratory health plan database and applying the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study.21 Chronic kidney disease was ascertained as glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 at the index ECG or at any time during the covariate ascertainment period or evidence of chronic dialysis. For continuous covariates (body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol), we fitted a within‐person linear slope of change over the covariate ascertainment period and used the slope and the average across the covariate ascertainment period as adjustment variables.

Standard International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition codes (listed in Table S1) were used for the ascertainment of cardiovascular events (coronary heart disease, transient ischemic attack [TIA], ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, HF) and chronic dialysis. Prior longitudinal studies among KPNC members have demonstrated the validity of discharge diagnostic codes for myocardial infarction,22 stroke23 and HF.24 Our mortality data relied on 3 complementary sources: official state of California death certificate data, health plan in‐hospital mortality, and Social Security Administration Death Files, and were satisfactorily validated against the National Death Index.25 The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute, and the need for individual signed informed consent was waived.

Statistical Analysis

Because the calculation of Cornell voltage and thus Cornell product LVH is sex specific, all analyses were performed separately in men and women. The continuous variables are described in terms of averages over the covariate ascertainment period and slope (linear change per year). The distribution of demographic data and risk factors were tabulated across the 5 ECG LVH trajectories. Differences in continuous variables were tested using ANOVA, whereas differences in categorical variables were tested using the chi‐square test.

To avoid bias arising from early CHD, stroke, and HF events affecting ECGs and covariates, follow‐up time for each person started the day after his/her last ECG in the 1995–2008 period (no ECGs were available after 2008). Age‐adjusted incidence rates of CHD, TIA, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and HF per 10 000 person‐years were calculated using Poisson regression. Right censoring was applied at death, discontinuation of health plan membership, or December 31, 2014, whichever took place first. Discontinuation of membership was defined as 2 consecutive years of disenrollment, even if the patient rejoined the health plan at a later time. The median (range) follow‐up time was 4.8 (<1–9.3) years. For each CVD end point, we summarized the event‐free survival experience of the 5 ECG LVH trajectories using Kaplan–Meier curves and the log‐rank test.

To examine the independent association of ECG LVH trajectories with each cardiovascular outcome (relative to persistent absence of LVH), we employed Cox proportional hazards models, excluding persons with a history of the CVD condition of interest. We applied 2 levels of multivariable adjustment: first, a model adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, number of ECGs, and time between index and last ECG (model 1); then a model containing, in addition to model 1 covariates, smoking status, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease plus average of and change in body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and HDL (model 2). A second set of models considered any LVH versus persistently absent LVH. We performed supplemental sex‐specific modeling of standardized (ie, divided by sex‐specific SD) Cornell product and covariates as time‐dependent exposures where follow‐up time started at the index (first) ECG rather than at the last ECG. This analytical cohort was larger (88 256 men and 121 272 women) than the one used for the LVH trajectories because patients with CVD events in the covariate ascertainment period were not excluded. We performed (with both model 1 and model 2 covariates) a priori tests for interaction of Cornell product with black race, Asian/Pacific Islander race, and Latino race, respectively, separately in each sex. In addition, we used 2 different statistical approaches to assess the potential utility of including Cornell product (average or last measure) or the ECG LVH trajectories on top of the 10‐year risk pooled cohort equation for atherosclerotic CVD (CHD plus stroke)26: (1) the discriminative capacity of the model using the concordance index (Harrell's C statistic), and (2) reclassification improvement using the net reclassification improvement index.27 For the assessment of reclassification improvement, we defined 4 risk categories (low, intermediate‐low, intermediate‐high, and high) with cutoff points <5%, 5% to <7.5%, 7.5% to <10%, and ≥10%, as previously used.28 To correct for bias in the net reclassification improvement estimation among individuals with intermediate risk, we used the method proposed by Paynter and Cook.29 Because the pooled cohort equation was derived using black and white patients only, this analysis was done including only cohort participants of those 2 ethnic groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.13 (SAS Institute, Inc) and with the R statistical package.

Results

At the time of the baseline (index) ECG, the mean (SD) age of the male cohort was 58 (12) years (Table 1). Men had an average of 3 ECGs spaced over an average period of 7 years, 59% were white, 13% were Asian and Pacific Islander, 13% were Latino, 8% were black, 5% were mixed, and 0.50% were Native American. Twelve percent reported current smoking, 29% former smoking, and 8% quitting smoking during the covariate ascertainment period. Diabetes mellitus was present in 21% of men, hypertension diagnosis or treatment in 81%, and chronic kidney disease in 31%; 60% were taking cholesterol‐lowering drugs. Average levels of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, body mass index, total and HDL cholesterol, and ECG‐derived Cornell product are given in Table 1. Of note, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and total cholesterol tended to decrease over the covariate ascertainment period, whereas average body mass index did not change and HDL and Cornell product showed an increase (ie, positive slope). The mean (SD) age of women was also 58 (13) years, and their average number of ECGs, time between index and last ECG, and race\ethnic breakdown were similar to the men's values (Table 1). About 8% reported current smoking, 22% former smoking, and 7% quitting during the covariate ascertainment period. Diabetes mellitus was present in 18% of women, hypertension diagnosis or treatment in 75%, and chronic kidney disease in 33%; 54% were taking cholesterol‐lowering drugs. Average levels of systolic and diastolic blood pressure and body mass index were similar to those in men, while average HDL and average Cornell product were higher in women than men. Changes in continuous risk factors were also similar to those in men, with the exception of a larger (double) increase in Cornell product.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort at the CAP (Between Index ECG and Last ECG)

| Men (n=75 412) | Women (n=107 954 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at index ECG, mean±SD, y | 57.7±12.2 | 57.9±12.6 |

| Age categories at index ECG, No. (%) | ||

| 30–54 y | 32 350 (42.9) | 46 848 (43.4) |

| 55–64 y | 20 942 (27.8) | 28 345 (26.3) |

| 65–84 y | 21 557 (28.6) | 31 646 (29.3) |

| ≥85 y | 563 (0.7) | 1115 (1.0) |

| No. of ECGs, mean±SD (min–max) | 3.1±1.4 (2–19) | 3.2±1.5 (2–19) |

| Time between index and last ECG, mean±SD (min–max), y | 6.6±3.4 (0.5–16.1) | 6.7±3.4 (0.5–16.1) |

| Race\ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| White | 44 456 (59.0) | 60 468 (56.0) |

| Black | 6246 (8.3) | 10 670 (9.9) |

| Asian and Pacific Islander | 9897 (13.1) | 14 231 (13.2) |

| Latino | 9584 (12.7) | 14 706 (13.6) |

| Mixed | 4002 (5.3) | 6724 (6.2) |

| Native American | 386 (0.5) | 550 (0.5) |

| Missing | 841 (1.1) | 605 (0.6) |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||

| Never | 30 439 (40.4) | 61 509 (57.0) |

| Former | 22 064 (29.3) | 23 850 (22.1) |

| Current | 9040 (12.0) | 9036 (8.4) |

| Quitter in the CAP | 6002 (8.0) | 7158 (6.6) |

| New smoker in the CAP | 37 (0.0) | 29 (0.0) |

| Missing | 7830 (10.4) | 6372 (5.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||

| Average, mm Hg | 130.1±11.8 | 130.2±12.9 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −0.4±4.7 | −0.2±4.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||

| Average, mm Hg | 75.9±8.1 | 74.2±7.9 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −0.6±2.9 | −0.5±2.7 |

| Body mass index | ||

| Average, kg/m2 | 29.3±5.4 | 29.4±6.9 |

| Slope (∆ in kg/m2 per y) in the CAP | 0.0±0.6 | −0.1±0.8 |

| Total cholesterol | ||

| Average, mg/dL | 190.1±34.7 | 204.1±33.9 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | −3.2±8.5 | −2.0±8.3 |

| HDL cholesterol | ||

| Average, mg/dL | 45.8±11.1 | 56.4±13.8 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | 0.2±1.7 | 0.2±2.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 15 630 (20.7) | 18 986 (17.6) |

| Hypertensiona at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | ||

| Diagnosis only | 3617 (4.8) | 5781 (5.4) |

| Treatment only | 17 864 (23.7) | 18 386 (17.0) |

| Both | 39 657 (52.6) | 56 718 (52.5) |

| None | 14 274 (18.9) | 27 069 (25.1) |

| Cholesterol‐lowering drugs at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 45 081 (59.8) | 57 893 (53.6) |

| Chronic kidney diseaseb at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 23 691 (31.4) | 35 317 (32.7) |

| ECG‐derived Cornell product | ||

| Average, mm×ms | 1316.5±523.9 | 1547.5±486.2 |

| Slope (∆ in mm×ms per y) in the CAP | 7.7±173.0 | 14.6±162.9 |

CAP indicates covariate ascertainment period; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein.

Outpatient diagnoses or antihypertensive treatment.

Glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or chronic dialysis.

Overall, among men, persistent LVH was seen in 1.3%, new development of LVH in 3.0%, regression of LVH in 1.6%, variable pattern in 2.4%, and persistently absent LVH in 92% (Table 2). Persistent LVH was more common among Native American (2.8%) and black (1.8%) men and least common in white men (1.1%); new development of LVH was more common among black men (4.3%) and least common among Asian men (2.4%); regression of LVH was also more frequently seen among black men (2.2%) and was least observed in men of mixed ethnicity (1.4%); variable pattern was highest in black men (3.9%) and lowest in Asian and Pacific Islander men (2.1%). Any LVH was present in 8.3% of men overall and was highest in black men (12.3%) and lowest in Asian and Pacific Islander men (7.6%) (Table 2). Among women overall, persistent LVH was seen in 1.9%, new development of LVH in 4.3%, regression of LVH in 1.8%, variable pattern in 3.7%, and persistently absent LVH in 88%. Persistent LVH was more common among black women (3.0%) and least common in Asian and Pacific Islanders (1.1%); new development of LVH was more common among Native American (5.5%) and black women (5.3%) and least common in Asian and Pacific Islanders (2.6%); regression of LVH was also more frequently seen among black women (2.6%) and was least observed in mixed women (1.3%); variable pattern was highest in Native American (6.0%) and black women (5.8%) and lowest in Asian and Pacific Islander women (2.5%). Any LVH was present in 11.7% of women overall, and was highest in black women (16.7%) and lowest in Asian and Pacific Islander women (7.8%).

Table 2.

ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories According to Sex and Race/Ethnicity

| ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories | Men, No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n=44 456) | Black (n=6246) | Asian and Pacific Islander (n=9897) | Latino (n=9584) | Mixed (n=4002) | Native American (n=386) | Missing (n=841) | All (N=75 412) | |

| Persistent | 510 (1.1) | 115 (1.8) | 125 (1.3) | 134 (1.4) | 52 (1.3) | 11 (2.8) | 12 (1.4) | 959 (1.3) |

| New development | 1365 (3.1) | 271 (4.3) | 236 (2.4) | 253 (2.6) | 101 (2.5) | 11 (2.8) | 20 (2.4) | 2257 (3.0) |

| Regression | 668 (1.5) | 140 (2.2) | 181 (1.8) | 160 (1.7) | 57 (1.4) | 8 (2.1) | 10 (1.2) | 1224 (1.6) |

| Variable pattern | 1021 (2.3) | 242 (3.9) | 205 (2.1) | 207 (2.2) | 136 (3.4) | 11 (2.8) | 7 (0.8) | 1829 (2.4) |

| Persistently absent | 40 892 (92.0) | 5478 (87.7) | 9150 (92.5) | 8830 (92.1) | 3656 (91.4) | 345 (89.4) | 792 (94.2) | 69 143 (91.7) |

| Any LVHa | 3564 (8.0) | 768 (12.3) | 747 (7.6) | 754 (7.9) | 346 (8.6) | 41 (10.6) | 49 (5.8) | 6269 (8.3) |

| Women, No. (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (n=60 468) | Black (n=10 670) | Asian and Pacific Is lander (n=14 231) | Latino (n=14 706) | Mixed (n=6724) | Native‐Americans (n=550) | Missing (n=605) | All (N=107 954) | |

| Persistent | 1165 (1.9) | 322 (3.0) | 158 (1.1) | 275 (1.9) | 136 (2.0) | 4 (0.7) | 9 (1.5) | 2069 (1.9) |

| New development | 2844 (4.7) | 563 (5.3) | 370 (2.6) | 522 (3.5) | 291 (4.3) | 30 (5.5) | 14 (2.3) | 4634 (4.3) |

| Regression | 1031 (1.7) | 279 (2.6) | 233 (1.6) | 274 (1.9) | 86 (1.3) | 10 (1.8) | 6 (1.0) | 1919 (1.8) |

| Variable pattern | 2211 (3.7) | 616 (5.8) | 351 (2.5) | 437 (3.0) | 315 (4.7) | 33 (6.0) | 8 (1.3) | 3971 (3.7) |

| Persistently absent | 53 217 (88.0) | 8890 (83.3) | 13 119 (92.2) | 13 198 (89.8) | 5896 (87.7) | 473 (86.0) | 568 (93.9) | 95 361 (88.3) |

| Any LVHa | 7251 (12.0) | 1780 (16.7) | 1112 (7.8) | 1508 (10.2) | 828 (12.3) | 77 (14.0) | 37 (6.1) | 12 593 (11.7) |

LVH indicates left ventricular hypertrophy.

Persistent, new development, or regression or variable pattern.

In men, when comparing across LVH trajectories, persistent LVH was associated with the highest average systolic blood pressure and body mass index, the greater proportion of patients with hypertension diagnosis or treatment (93%), and the largest negative slopes of systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Table 3). As expected, the average Cornell product was highest in the group with persistent LVH and lowest in the group with persistently absent LVH, and tended to be higher in the group with new development compared with those with regression or variable pattern. As expected, new LVH development was associated with the highest positive slope of Cornell product, whereas regression of LVH was associated with the most negative slope of Cornell product over time. Variable pattern of LVH was associated with slightly older age, greater number of ECGs, longer time between first (index) and last ECG, higher use of cholesterol‐lowering drugs and higher burden of chronic kidney disease (Table 3). Black men tended to be overrepresented in all the nonpersistently absent trajectories, particularly in the variable LVH pattern. Compared with persistently absent LVH, men with any LVH tended to be older, to have higher systolic blood pressure, and to have higher prevalence of hypertension, cholesterol‐lowering drug use, and chronic kidney disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations Between ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories and Study Covariates Among Men

| Persistent (n=959) | New Development (n=2257) | Regression (n=1224) | Variable Pattern (n=1829) | Any LVH (n=6269) | Persistently Absent (n=69 143) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index ECG, mean±SD, y | 61.3±12.7 | 62.1±12.6 | 58.9±12.6 | 61.6±12.7 | 61.2±12.7 | 57.4±12.2 |

| Age categories at index ECG, No. (%) | ||||||

| 30–54 y | 316 (33.0) | 668 (29.6) | 500 (40.8) | 578 (31.6) | 2062 (32.9) | 30 288 (43.8) |

| 55–64 y | 257 (26.8) | 604 (26.8) | 305 (24.9) | 462 (25.3) | 1628 (26.0) | 19 314 (27.9) |

| 65–84 y | 366 (38.2) | 933 (41.3) | 406 (33.2) | 756 (41.3) | 2461 (39.3) | 19 096 (27.6) |

| ≥85 y | 20 (2.1) | 52 (2.3) | 13 (1.1) | 33 (1.8) | 118 (1.9) | 445 (0.6) |

| No. of ECGs, mean±SD | 2.9±1.3 | 3.1±1.3 | 3.0±1.3 | 5.0±1.9 | 3.6±1.7 | 3.1±1.3 |

| Time between index and last ECG, mean±SD, y | 5.7±3.3 | 6.8±3.4 | 6.4±3.3 | 8.2±3.3 | 7.0±3.5 | 6.6±3.4 |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Never | 389 (40.6) | 864 (38.3) | 464 (37.9) | 685 (37.5) | 2402 (38.3) | 28 037 (40.5) |

| Former | 273 (28.5) | 656 (29.1) | 364 (29.7) | 538 (29.4) | 1831 (29.2) | 20 233 (29.3) |

| Current | 119 (12.4) | 263 (11.7) | 143 (11.7) | 186 (10.2) | 711 (11.3) | 8329 (12.0) |

| Quitter in the CAP | 56 (5.8) | 144 (6.4) | 94 (7.7) | 145 (7.9) | 439 (7.0) | 5563 (8.0) |

| New smoker in the CAP | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.0) | 34 (0.0) |

| Missing | 122 (12.7) | 329 (14.6) | 159 (13.0) | 273 (14.9) | 883 (14.1) | 6947 (10.0) |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Average, mm Hg | 135.7±14.7 | 133.8±13.8 | 133.0±13.1 | 133.6±13.3 | 133.9±13.7 | 129.7±11.6 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −0.7±4.9 | −0.4±4.4 | −0.9±4.2 | −0.7±3.3 | −0.6±4.2 | −0.3±3.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Average, mm Hg | 76.4±9.9 | 75.6±9.3 | 76.4±9.1 | 75.2±9.0 | 75.8±9.3 | 76.0±8.0 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −1.0±3.1 | −0.6±2.9 | −0.9±2.5 | −0.8±2.3 | −0.8±2.7 | −0.6±2.1 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Average, kg/m2 | 29.7±5.1 | 28.7±5.1 | 29.5±5.7 | 28.9±5.4 | 29.1±5.3 | 29.3±5.4 |

| Slope (∆ in kg/m2 per y) in the CAP | 0.0±0.5 | −0.1±0.5 | 0.0±0.5 | −0.1±0.5 | 0.0±0.5 | 0.0±0.5 |

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| Average, mg/dL | 182.8±34.7 | 185.3±34.9 | 186.4±33.9 | 184.1±33.5 | 184.8±34.3 | 190.6±34.7 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | −3.7±7.5 | −3.4±6.5 | −3.8±9.8 | −3.6±6.0 | −3.5±7.4 | −3.1±6.8 |

| HDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Average, mg/dL | 44.3±10.9 | 45.5±11.5 | 45.4±11.5 | 45.8±11.9 | 45.4±11.6 | 45.8±11.1 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | 0.1±1.6 | 0.2±1.4 | 0.2±1.6 | 0.1±1.2 | 0.2±1.4 | 0.2±1.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 214 (22.3) | 452 (20.0) | 286 (23.4) | 390 (21.3) | 1342 (21.4) | 14 288 (20.7) |

| Hypertension at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | ||||||

| Diagnosis only | 39 (4.1) | 99 (4.4) | 45 (3.7) | 36 (2.0) | 219 (3.5) | 3398 (4.9) |

| Treatment only | 252 (26.3) | 713 (31.6) | 303 (24.8) | 622 (34.0) | 1890 (30.1) | 15 974 (23.1) |

| Both | 605 (63.1) | 1206 (53.4) | 782 (63.9) | 1101 (60.2) | 3694 (58.9) | 35 963 (52.0) |

| None | 63 (6.6) | 239 (10.6) | 94 (7.7) | 70 (3.8) | 466 (7.4) | 13 808 (20.0) |

| Cholesterol‐lowering drugs at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 648 (67.6) | 1466 (65.0) | 801 (65.4) | 1251 (68.4) | 4166 (66.5) | 40 915 (59.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 411 (42.9) | 972 (43.1) | 504 (41.2) | 952 (52.1) | 2839 (45.3) | 20 852 (30.2) |

| ECG‐derived Cornell product | ||||||

| Average, mm×ms | 3122.7±453.2 | 2288.3±414.5 | 2268.8±323.8 | 2245.2±378.0 | 2399.5±500.1 | 1218.3±400.9 |

| Slope (∆ in mm×ms per y) in the CAP | 24.7±178.6 | 222.1±238.3 | −179.8±216.6 | 26.5±117.8 | 52.9±250.2 | 3.5±89.6 |

CAP indicates covariate ascertainment period; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

Among women, those with persistent LVH tended to be older, to have higher average systolic blood pressure and body mass index, to more likely use cholesterol‐lowering drugs, and to show the highest average Cornell product and the most negative slope of systolic blood pressure (Table 4). Similar to men, new LVH development in women was associated with the highest positive slope of Cornell product, whereas regression of LVH was associated with the most negative slope of Cornell product. Women presenting with variable pattern of LVH had greater number of ECGs, longer time between first (index) and last ECG, and highest prevalence of hypertension (93%) and chronic kidney disease (53%). Compared with persistently absent LVH, women with any LVH tended to be older, to have higher systolic blood pressure, and to have higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cholesterol‐lowering drug use, and chronic kidney disease (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bivariate Associations Between ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories and Study Covariates Among Women

| Persistent (n=2069) | New Development (n=4634) | Regression (n=1919) | Variable Pattern (n=3971) | Any LVH (n=12 593) | Persistently Absent (n=95 361) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index ECG, mean±SD, y | 65.4±12.3 | 63.1±12.9 | 61.1±12.7 | 62.3±12.6 | 62.9±12.7 | 57.2±12.5 |

| Age categories at index ECG, No. (%) | ||||||

| 30–54 y | 440 (21.3) | 1324 (28.6) | 633 (33.0) | 1169 (29.4) | 3566 (28.3) | 43 282 (45.4) |

| 55–64 y | 521 (25.2) | 1110 (24.0) | 528 (27.5) | 1004 (25.3) | 3163 (25.1) | 25 182 (26.4) |

| 65–84 y | 1028 (49.7) | 2096 (45.2) | 710 (37.0) | 1725 (43.4) | 5559 (44.1) | 26 087 (27.4) |

| ≥85 y | 80 (3.9) | 104 (2.2) | 48 (2.5) | 73 (1.8) | 305 (2.4) | 810 (0.8) |

| No. of ECGs, mean±SD | 3.0±1.4 | 3.2±1.3 | 3.0±1.2 | 5.1±1.9 | 3.7±1.8 | 3.2±1.4 |

| Time between index and last ECG, mean±SD, y | 5.9±3.2 | 6.9±3.4 | 6.0±3.2 | 8.1±3.3 | 7.0±3.4 | 6.6±3.3 |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Never | 1205 (58.2) | 2570 (55.5) | 1060 (55.2) | 2135 (53.8) | 6970 (55.3) | 54 539 (57.2) |

| Former | 431 (20.8) | 1009 (21.8) | 413 (21.5) | 875 (22.0) | 2728 (21.7) | 21 122 (22.1) |

| Current | 139 (6.7) | 355 (7.7) | 170 (8.9) | 319 (8.0) | 983 (7.8) | 8053 (8.4) |

| Quitter in the CAP | 98 (4.7) | 259 (5.6) | 115 (6.0) | 260 (6.5) | 732 (5.8) | 6426 (6.7) |

| New smoker in the CAP | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.0) | 24 (0.0) |

| Missing | 195 (9.4) | 438 (9.5) | 160 (8.3) | 382 (9.6) | 1175 (9.3) | 5197 (5.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Average, mm Hg | 137.8±14.2 | 135.5±13.6 | 134.5±13.2 | 135.4±13.4 | 135.7±13.6 | 129.4±12.6 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −0.5±3.9 | −0.3±4.0 | −0.4±3.4 | −0.3±3.6 | −0.4±3.8 | −0.1±3.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| Average, mm Hg | 74.9±8.8 | 74.6±8.6 | 74.7±8.3 | 74.4±8.3 | 74.6±8.5 | 74.2±7.8 |

| Slope (∆ in mm Hg per y) in the CAP | −0.7±2.1 | −0.6±1.9 | −0.7±1.9 | −0.6±2.2 | −0.6±2.0 | −0.5±2.0 |

| Body mass index | ||||||

| Average, kg/m2 | 31.0±7.5 | 29.9±7.1 | 30.8±7.4 | 30.0±7.2 | 30.2±7.3 | 29.3±6.9 |

| Slope (∆ in kg/m2 per y) in the CAP | −0.2±0.6 | −0.1±0.6 | −0.1±0.9 | −0.1±0.7 | −0.1±0.7 | −0.1±0.6 |

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| Average, mg/dL | 198.5±34.1 | 202.1±33.7 | 199.1±34.7 | 201.1±33.1 | 200.7±33.7 | 204.6±33.8 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | −2.7±7.8 | −2.5±6.5 | −2.8±7.1 | −2.8±5.5 | −2.7±6.6 | −2.0±7.1 |

| HDL cholesterol | ||||||

| Average, mg/dL | 53.5±12.6 | 56.0±14.2 | 54.7±13.8 | 55.4±13.5 | 55.2±13.7 | 56.6±13.8 |

| Slope (∆ in mg/dL per y) in the CAP | 0.1±1.7 | 0.1±1.7 | 0.2±2.3 | 0.1±1.6 | 0.1±1.8 | 0.2±1.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 450 (21.7) | 883 (19.1) | 500 (26.1) | 803 (20.2) | 2636 (20.9) | 16 350 (17.1) |

| Hypertension at any time in the CAP, n (%) | ||||||

| Diagnosis only | 71 (3.4) | 210 (4.5) | 91 (4.7) | 136 (3.4) | 508 (4.0) | 5273 (5.5) |

| Treatment only | 476 (23.0) | 1111 (24.0) | 381 (19.9) | 1038 (26.1) | 3006 (23.9) | 15 380 (16.1) |

| Both | 1374 (66.4) | 2738 (59.1) | 1278 (66.6) | 2519 (63.4) | 7909 (62.8) | 48 809 (51.2) |

| None | 148 (7.2) | 575 (12.4) | 169 (8.8) | 278 (7.0) | 1170 (9.3) | 25 899 (27.2) |

| Cholesterol‐lowering drugs at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 1357 (65.6) | 2776 (59.9) | 1222 (63.7) | 2547 (64.1) | 7902 (62.7) | 49 991 (52.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease at any time in the CAP, No. (%) | 1037 (50.1) | 2106 (45.4) | 889 (46.3) | 2094 (52.7) | 6126 (48.6) | 29 191 (30.6) |

| ECG‐derived Cornell product | ||||||

| Average, mm×ms | 3104.2±449.5 | 2334.5±361.2 | 2303.3±282.6 | 2269.6±317.6 | 2435.7±462.3 | 1430.2±348.5 |

| Slope (∆ in mm×ms per y) in the CAP | 36.7±163.2 | 178.4±183.6 | −154.5±156.3 | 33.6±97.0 | 57.7±193.3 | 10.2±83.2 |

CAP indicates covariate ascertainment period; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

The sex‐specific CHD, TIA, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and HF (unadjusted) survival experience according to LVH trajectory patterns is depicted in Figure S1. Consistently across cardiovascular end points and in both sexes, patients with persistent, variable, or new development of LVH pattern exhibited the worst survival, whereas those with regression of LVH tended to be in the middle.

In men, Cox regression models (with minimal adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, number of ECGs, and time between first and last ECG) examining the relationship of LVH trajectories with CVD outcomes indicated that the strongest associations for each outcome were new development of LVH with CHD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.65; 95% CI, 1.48–1.85), persistent LVH with TIA (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.10–2.04); new development of LVH with ischemic stroke (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.27–1.81); persistent LVH with hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.44–3.71); and persistent LVH with HF (HR, 3.12; 95% CI, 2.71–3.59). After multivariable adjustment for baseline and change in risk factors, these associations were somewhat attenuated but remained statistically significant (Table 5). Of note, new development of LVH was not significantly associated with TIA, regression of LVH was not significantly associated with CHD or any of the stroke subtypes, and variable pattern was not significantly associated with TIA or hemorrhagic stroke. Any LVH was significantly associated with all CVD outcomes except TIA and the strongest association was with HF.

Table 5.

Associations Between ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories and Cardiovascular End Points Among Men

| Persistent (n=959) | New Development (n=2257) | Regression (n=1224) | Variable Pattern (n=1829) | Any LVH (n=6269) | Persistently Absent (n=69 143) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD (n=6475) | ||||||

| No. of events | 139 | 335 | 119 | 256 | 849 | 5626 |

| No. of person‐y | 3781 | 8624 | 5083 | 6770 | 24 258 | 294 116 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 269 (0.11) | 283 (0.09) | 195 (0.11) | 288 (0.09) | 265 (0.08) | 169 (0.07) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.64 (1.38–1.94) | 1.65 (1.48–1.85) | 1.17 (0.98–1.41) | 1.33 (1.17–1.51) | 1.46 (1.36–1.57) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.45 (1.22–1.72) | 1.51 (1.35–1.69) | 1.06 (0.88–1.27) | 1.24 (1.09–1.41) | 1.34 (1.24–1.44) | 1.00 [reference] |

| TIA (n=1959) | ||||||

| No. of events | 42 | 69 | 31 | 65 | 207 | 1752 |

| No. of person‐y | 4038 | 9197 | 5266 | 7146 | 25 647 | 304 516 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 71 (0.20) | 52 (0.18) | 47 (0.22) | 66 (0.18) | 58 (0.15) | 49 (0.13) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.50 (1.10–2.04) | 1.04 (0.81–1.32) | 0.97 (0.68–1.39) | 1.01 (0.78–1.30) | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.44 (1.06–1.95) | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) | 0.94 (0.66–1.34) | 0.95 (0.73–1.22) | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Ischemic stroke (n=2579) | ||||||

| No. of events | 51 | 132 | 46 | 119 | 348 | 2231 |

| No. of person‐y | 4022 | 9116 | 5281 | 7078 | 25 497 | 304 126 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 81 (0.18) | 93 (0.15) | 66 (0.19) | 113 (0.15) | 91 (0.13) | 60 (0.11) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.39 (1.05–1.83) | 1.52 (1.27–1.81) | 1.10 (0.82–1.47) | 1.40 (1.16–1.70) | 1.39 (1.24–1.56) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.25 (0.95–1.66) | 1.35 (1.13–1.61) | 1.01 (0.76–1.36) | 1.28 (1.06–1.55) | 1.26 (1.12–1.41) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Hemorrhagic stroke (n=577) | ||||||

| No. of events | 18 | 32 | 14 | 22 | 86 | 491 |

| No. of person‐y | 4061 | 9243 | 5334 | 7215 | 25 853 | 306 855 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 29 (0.34) | 23 (0.31) | 20 (0.36) | 21 (0.33) | 23 (0.27) | 13 (0.24) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 2.31 (1.44–3.71) | 1.71 (1.19–2.45) | 1.52 (0.89–2.59) | 1.26 (0.81–1.96) | 1.63 (1.29–2.05) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 2.16 (1.35–3.48) | 1.49 (1.04–2.14) | 1.39 (0.81–2.36) | 1.11 (0.71–1.73) | 1.45 (1.15–1.83) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Heart failure (n=5288) | ||||||

| No. of events | 209 | 410 | 151 | 368 | 1138 | 4150 |

| No. of person‐y | 3682 | 8512 | 5042 | 6628 | 23 863 | 300 310 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 310 (0.11) | 264 (0.10) | 203 (0.12) | 323 (0.10) | 276 (0.09) | 101 (0.08) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 3.12 (2.71–3.59) | 2.53 (2.28–2.80) | 2.03 (1.72–2.38) | 2.29 (2.04–2.56) | 2.45 (2.29–2.62) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 2.76 (2.40–3.18) | 2.29 (2.07–2.54) | 1.81 (1.54–2.13) | 2.14 (1.91–2.39) | 2.23 (2.09–2.39) | 1.00 [reference] |

HR indicates hazard ratio; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

In women, minimally adjusted Cox regression models examining the relationship of LVH trajectories with CVD outcomes yielded similar results to men for HF (strongest HRs for persistent LVH), but differed for CHD and stroke types (Table 6). In women, regression of LVH was significantly associated with TIA (HR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.06–1.71), persistent LVH had the highest HR for ischemic stroke (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.33–1.88), and variable pattern had the highest HR for hemorrhagic stroke (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.03–1.90). Similar to men, adjustment for baseline and change in risk factors did not explain these associations, although there was attenuation of risk estimates. Any LVH was significantly associated with all CVD outcomes (including TIA) and, in agreement with findings among men, the strongest association was with HF.

Table 6.

Associations Between ECG‐Derived LVH Trajectories and Cardiovascular End Points Among Women

| Persistent (n=2069) | New Development (n=4634) | Regression (n=1919) | Variable Pattern (n=3971) | Any LVH (n=12 593) | Persistently Absent (n=95 361) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHD (n=5213) | ||||||

| No. of events | 199 | 386 | 133 | 400 | 1118 | 4095 |

| No. of person‐y | 8458 | 18 999 | 8188 | 15 504 | 51 151 | 425 761 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 131 (0.11) | 126 (0.10) | 112 (0.12) | 167 (0.10) | 137 (0.09) | 78 (0.08) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.67 (1.45–1.93) | 1.62 (1.45–1.79) | 1.46 (1.23–1.74) | 1.52 (1.36–1.69) | 1.57 (1.47–1.68) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.46 (1.26–1.69) | 1.45 (1.30–1.61) | 1.27 (1.07–1.51) | 1.37 (1.23–1.53) | 1.40 (1.31–1.50) | 1.00 [reference] |

| TIA (n=2894) | ||||||

| No. of events | 89 | 168 | 70 | 190 | 517 | 2377 |

| No. of person‐y | 8695 | 19 469 | 8319 | 15 943 | 52 427 | 430 535 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 59.8 (0.15) | 55.7 (0.13) | 59.7 (0.16) | 80.4 (0.13) | 64.4 (0.12) | 46.0 (0.10) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.32 (1.06–1.63) | 1.21 (1.03–1.41) | 1.35 (1.06–1.71) | 1.25 (1.07–1.46) | 1.26 (1.14–1.39) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.22 (0.98–1.51) | 1.14 (0.97–1.33) | 1.27 (1.00–1.61) | 1.19 (1.02–1.40) | 1.19 (1.08–1.31) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Ischemic stroke (n=3611) | ||||||

| No. of events | 136 | 250 | 97 | 264 | 747 | 2864 |

| No. of person‐y | 8613 | 19 383 | 8311 | 15 892 | 52 200 | 430 341 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 79.7 (0.13) | 73.5 (0.12) | 74.0 (0.14) | 99.5 (0.12) | 82.4 (0.11) | 51.2 (0.10) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.58 (1.33–1.88) | 1.42 (1.25–1.62) | 1.50 (1.22–1.84) | 1.39 (1.21–1.58) | 1.45 (1.33–1.57) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.38 (1.16–1.65) | 1.26 (1.11–1.44) | 1.36 (1.11–1.66) | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | 1.30 (1.19–1.41) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Hemorrhagic stroke (n=719) | ||||||

| No. of events | 20 | 48 | 14 | 49 | 131 | 588 |

| No. of person‐y | 8812 | 19 688 | 8434 | 16 194 | 53 129 | 433 739 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 12 (0.32) | 15 (0.27) | 11 (0.34) | 19 (0.26) | 15 (0.24) | 11 (0.21) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 1.18 (0.75–1.85) | 1.35 (1.00–1.81) | 1.06 (0.62–1.80) | 1.40 (1.03–1.90) | 1.30 (1.07–1.57) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 1.04 (0.66–1.63) | 1.18 (0.87–1.59) | 0.98 (0.58–1.67) | 1.28 (0.94–1.73) | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Heart failure (n=6019) | ||||||

| No. of events | 322 | 609 | 204 | 550 | 1685 | 4334 |

| No. of person‐y | 8214 | 18 681 | 8059 | 15 306 | 50 260 | 426 916 |

| Age‐adjusted rate per 10 000 person‐y (SE) | 166.1 (0.10) | 157.6 (0.09) | 141.2 (0.11) | 186.9 (0.09) | 165.4 (0.09) | 70.0 (0.08) |

| Model 1 HR (95% CI) | 2.39 (2.13–2.68) | 2.20 (2.02–2.39) | 2.10 (1.83–2.42) | 1.85 (1.68–2.03) | 2.10 (1.98–2.22) | 1.00 [reference] |

| Model 2 HR (95% CI) | 2.03 (1.81–2.27) | 1.89 (1.74–2.06) | 1.80 (1.56–2.07) | 1.61 (1.47–1.77) | 1.81 (1.71–1.92) | 1.00 [reference] |

CHD, coronary heart disease; HR, hazard ratio; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

In supplemental time‐dependent analyses in men overall (Table S2), continuous standardized Cornell product was more strongly associated with HF than with CHD or stroke. In fully adjusted models in men, 2 interactions reached a nominal level of statistical significance, namely the interaction of Cornell voltage product with black race as predictors of CHD (P=0.02) and the interaction of Cornell product with black race as predictors of ischemic stroke (P=0.005). Accordingly, the Cornell product had a more marked association with CHD and ischemic stroke among black men than among white men. Parallel analyses in women identified statistically significant Cornell voltage product by Asian/Pacific Islander race interactions for TIA (P=0.03), ischemic stroke (P=0.0001), and hemorrhagic stroke (P=0.005). Cornell voltage product was inversely associated with TIA in Asian/Pacific Islander and was not associated with TIA in white women. On the other hand, there was a significant association of the Cornell voltage product with ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke among Asian/Pacific Islander women, whereas no associations were observed in white women (Table S3).

The Harrell's C statistic (which represents the area under the curve in time‐to‐event analysis) after the addition of either average, latest Cornell product, or LVH trajectories to the 10‐year pooled cohort equation changed only marginally, although the increment (0.004, from 0.6491 to 0.6530) was statistically significant (P<0.0001) for LVH trajectories (Table S4). There was no reclassification after adding average Cornell product or the last Cornell voltage product. On the other hand, there was a modest reclassification after adding trajectories of LVH (4% in the full cohort and 6% in the subset with intermediate risk). By sex (data not shown), the reclassification after adding LVH trajectories was 3% (95% CI, 0.02–0.04) in the full cohort and 4% (95% CI, −0.01 to 0.09) in the subset with intermediate risk among men, and 5% (95% CI, 0.03–0.06) in the full cohort and 7% (95% CI, 0.02–0.13) in the subset with intermediate risk among women.

Discussion

This is the largest cohort for which serial measures of ECG‐derived LVH have been systematically evaluated, with over 2 million person‐years of follow‐up. The study demonstrates: (1) clear ethnic disparities in trajectories of LVH, and (2) an independent predictive value of LVH trajectories for incident CHD, stroke types, and HF in both men and women. In men, the association between the Cornell product as a time‐dependent variable with CHD and stroke was accentuated in blacks. In women, Cornell product as a time‐dependent variable was positively associated with both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke among Asian/Pacific Islanders, but not among whites. Finally, and in agreement with recent results of the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study,30 we found little evidence of additional improvement in discrimination or reclassification of 10‐year pooled cohort equation risk after consideration of either the average Cornell product or latest measure of Cornell product. However, we observed a modest but significant reclassification improvement after considering LVH trajectories, particularly in the subset with intermediate risk (6% overall, 4% in men, 7% in women), indicating that ECG LVH trajectories may have more clinical utility than isolated measurements.

Among men (notwithstanding the fact that the male Native American cohort was small, n=385), persistent LVH was more prominent among Native Americans and blacks, while new development, regression, and variable pattern of LVH were more frequently seen among blacks. Among women, persistent and regression of LVH were more common among blacks, whereas new development and variable pattern were more common among Native Americans. It is worth noting that these disparities existed in the setting of an integrated healthcare delivery system, where persons of all ethnic backgrounds have equal access to care and where systematic efforts have been successful in controlling rates of hypertension.20 Racial differences in some ECG LVH voltage criteria, showing greater precordial voltage measures in black versus white patients, are well documented in the literature.3, 31, 32, 33, 34 It has been argued, however, that use of these ECG criteria for detection of LVH may overestimate (relative to echocardiographic LVH as reference standard) white‐black differences in LVH prevalence. However, use of Cornell product criteria minimizes differences in test performance between black and white patients.35

In men, after multivariate adjustment for baseline and changes in risk factors, we found that the strongest association with CHD was with new development of LVH, and no association existed between regression of LVH and CHD. The only LVH trajectory associated with TIA was persistent LVH. Ischemic stroke was also more strongly associated with new development of LVH, while hemorrhagic stroke and HF were more strongly predicted by persistent LVH. In multivariate‐adjusted models in women, persistent and new development of LVH had a similar association with CHD, TIA was only significantly predicted by variable LVH pattern, ischemic stroke was more strongly predicted by persistent LVH, and no significant associations were found for hemorrhagic stroke. Similar to that seen in men, the strongest association for HF was for persistent LVH.

Because rates were lower in patients who experienced regression compared with those with persistent LVH, our findings are consistent with the Framingham study, where patients with evidence of LVH who had serial declines in voltage (compared with those with no serial change) were at lower risk, whereas those with serial increases in voltage were at greater risk for CVD.7 Our results also confirm, in a large, real‐world population, the findings observed in 2 sentinel clinical trials: (1) the HOPE (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation) trial indicating that regression (compared with persistence or development of LVH) with ramipril was associated with a reduction of composite outcome of CVD death, myocardial infarction, or stroke, independently of blood pressure changes36; and (2) the LIFE (Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension) trial, which demonstrated that regression of LVH during antihypertensive therapy was associated with lower likelihoods of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.37

Our data revealed ethnic differences in strengths of association between Cornell product as a time‐dependent covariate and CVD outcomes. In men, the Cornell voltage product was more strongly associated with CHD and ischemic stroke in blacks. In women, it was noteworthy that the Cornell product as a time‐dependent exposure was an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke in Asian/Pacific Islanders and Latinas but not among whites or blacks and was an independent risk factor for hemorrhagic stroke only for Asian/Pacific Islanders. Using data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey linked to the National Death Index, Havranek et al5 found that ECG LVH contributed more to the risk of cardiovascular mortality in blacks than it did in whites. In an analysis of the Framingham Heart Study and the Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study, the presence of LVH had a greater effect on all‐cause mortality in Asians compared with whites.38 Taken together, these results and ours should raise awareness that different measures of ECG LVH could have different meanings in different subgroups of patients. Potential physiological explanations include the pattern of hypertrophy (blacks tend to develop a concentric pattern, which is linked to poorer prognosis)39, 40 and/or pleiotropic genetic predisposition to LVH and atherosclerotic CVD and stroke.

Although reclassification was modest (4% in men and 7% in women with an intermediate‐risk profile), our results demonstrate potential clinical utility of ECG LVH trajectories. Longitudinal ECG assessments are inexpensive and are often incorporated into electronic health records. Therefore, a tool linked to the electronic health record could detect adverse ECG LVH trajectories and alert clinicians of heightened risk and even help tailor therapy to these patients. For example, the LIFE trial among 9193 hypertensive patients with ECG evidence of LVH demonstrated that stroke rate was reduced in the losartan treatment group compared with those treated with atenolol‐based therapy, suggesting an advantage of angiotensin receptor blockers over β‐blockers in these patients.41

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study include the extremely large sample size and the ethnic diversity of the sample, as well as the availability of serial measures of ECG‐derived LVH and covariates. Because ECG LVH is defined differently in men and women, it was important to examine risk relations stratifying by sex. As limitations, our data may not be generalizable to uninsured populations. Also, we focused on a patient population with multiple ECGs, which was not a random representation of Kaiser Permanente members. ECGs are performed in our health plan as part of routine medical care and not as a screening test in asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, it is likely that our multivariate models are still subject to residual confounding; for instance, we were unable to adjust for brain natriuretic peptides when considering HF. We focused on only one marker of ECG LVH, the product of Cornell voltage and QRS duration, because it has been shown to increase sensitivity of the ECG recognition of LVH at acceptable levels of specificity and has been demonstrated to predict risk during serial assessment over time.19, 37 Moreover, Cornell voltage has been shown to have greater diagnostic accuracy than Sokolow‐Lyon voltage and a closer correlation with echocardiographically assessed left ventricular mass.42, 43 Because both voltage and QRS duration are available in most commercially available ECG systems, this marker can be easily adopted by practitioners. Another limitation is that we did not consider other ECG phenotypes commonly associated with ECG LVH such as left ventricular strain pattern or increased negative P‐terminal force in lead V1.11 Another limitation of the design is that, if the randomly chosen index ECG was the last one, this precluded identifying a trajectory. Finally, we recognize the lack of echocardiographically defined LVH data in our cohort.

Conclusions

Trajectories of ECG‐derived LVH were significant indicators of future risk of CHD, stroke types, and HF after accounting for level and change in CVD risk factors. Future observational and clinical trial work should address the value of incorporating changes in ECG voltage‐QRS duration product in risk prediction and primary prevention strategies.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by grants from the Northern California Kaiser Permanente Division of Research Health Policy and Disparities Research Program and by the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute Community Benefits Program.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Ascertainment of Study End Points and Chronic Dialysis

Table S2. Associations Between Time‐Dependent Cornell Voltage Product and Cardiovascular End Points Among Men

Table S3. Associations Between Time‐Dependent Cornell Voltage Product and Cardiovascular End Points Among Women

Table S4. Model Calibration, Discriminative Capacity, and Reclassification for Incident CVD (CHD+Ischemic Stroke) Including White and Black Men and Women (Cutoffs for PCE: <5%, 5% to <7.5%, 7.5 to <10%, and ≥10%)

Figure S1. Kaplan‐Meir curves of coronary heart disease (CHD; A), transient ischemic attack (TIA; B), ischemic stroke (C), hemorrhagic stroke (D), and heart failure (E).

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004954 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004954.)

References

- 1. Brown DW, Giles WH, Croft JB. Left ventricular hypertrophy as a predictor of coronary heart disease mortality and the effect of hypertension. Am Heart J. 2000;140:848–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kannel WB, Gordon T, Offutt D. Left ventricular hypertrophy by electrocardiogram. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality in the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1969;71:89–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oberman A, Prineas RJ, Larson JC, LaCroix A, Lasser NL. Prevalence and determinants of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy among a multiethnic population of postmenopausal women (The Women's Health Initiative). Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pewsner D, Juni P, Egger M, Battaglia M, Sundstrom J, Bachmann LM. Accuracy of electrocardiography in diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy in arterial hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;335:711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Havranek EP, Froshaug DB, Emserman CD, Hanratty R, Krantz MJ, Masoudi FA, Dickinson LM, Steiner JF. Left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiovascular mortality by race and ethnicity. Am J Med. 2008;121:870–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnett DK, Rautaharju P, Crow R, Folsom AR, Ekelund LG, Hutchinson R, Tyroler HA, Heiss G. Black‐white differences in electrocardiographic left ventricular mass and its association with blood pressure (the ARIC study). Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levy D, Salomon M, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Prognostic implications of baseline electrocardiographic features and their serial changes in subjects with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1994;90:1786–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salles GF, Cardoso CR, Fiszman R, Muxfeldt ES. Prognostic impact of baseline and serial changes in electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy in resistant hypertension. Am Heart J. 2010;159:833–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selvetella G, Notte A, Maffei A, Calistri V, Scamardella V, Frati G, Trimarco B, Colonnese C, Lembo G. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with asymptomatic cerebral damage in hypertensive patients. Stroke. 2003;34:1766–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kohsaka S, Sciacca RR, Sugioka K, Sacco RL, Homma S, Di Tullio MR. Additional impact of electrocardiographic over echocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy for predicting the risk of ischemic stroke. Am Heart J. 2005;149:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsieh BP, Pham MX, Froelicher VF. Prognostic value of electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J. 2005;150:161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L, Celis H, Birkenhager WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Leonetti G, Sarti C, Tuomilehto J, Webster J, Yodfat Y. Prognostic significance of electrocardiographic voltages and their serial changes in elderly with systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;44:459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okin PM, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Borer JS, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy by the time‐voltage integral of the QRS complex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Devereux RB, Casale PN, Eisenberg RR, Miller DH, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic detection of left ventricular hypertrophy using echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass as the reference standard. Comparison of standard criteria, computer diagnosis and physician interpretation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3:82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crow RS, Prineas RJ, Rautaharju P, Hannan P, Liebson PR. Relation between electrocardiography and echocardiography for left ventricular mass in mild systemic hypertension (results from Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study). Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1233–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census‐based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casale PN, Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Campo E, Kligfield P. Improved sex‐specific criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy for clinical and computer interpretation of electrocardiograms: validation with autopsy findings. Circulation. 1987;75:565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Molloy TJ, Okin PM, Devereux RB, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic detection of left ventricular hypertrophy by the simple QRS voltage‐duration product. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okin PM, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic identification of increased left ventricular mass by simple voltage‐duration products. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large‐scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310:699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Selby JV, Fireman BH, Lundstrom RJ, Swain BE, Truman AF, Wong CC, Froelicher ES, Barron HV, Hlatky MA. Variation among hospitals in coronary‐angiography practices and outcomes after myocardial infarction in a large health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1888–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Klatsky AL, Friedman GD. Cohort study of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and risk of first ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iribarren C, Karter AJ, Go AS, Ferrara A, Liu JY, Sidney S, Selby JV. Glycemic control and heart failure among adult patients with diabetes. Circulation. 2001;103:2668–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arellano MG, Petersen GR, Petitti DB, Smith RE. The California Automated Mortality Linkage System (CAMLIS). Am J Public Health. 1984;74:1324–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC Jr, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PW, Jordan HS, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Tomaselli GF. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S49–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kerr KF, McClelland RL, Brown ER, Lumley T. Evaluating the incremental value of new biomarkers with integrated discrimination improvement. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muntner P, Colantonio LD, Cushman M, Goff DC Jr, Howard G, Howard VJ, Kissela B, Levitan EB, Lloyd‐Jones DM, Safford MM. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Pooled Cohort risk equations. JAMA. 2014;311:1406–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paynter NP, Cook NR. A bias‐corrected net reclassification improvement for clinical subgroups. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Okwuosa TM, Soliman EZ, Lopez F, Williams KA, Alonso A, Ferdinand KC. Left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiovascular disease risk prediction and reclassification in blacks and whites: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am Heart J. 2015;169:155–161.e155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chapman JN, Mayet J, Chang CL, Foale RA, Thom SA, Poulter NR. Ethnic differences in the identification of left ventricular hypertrophy in the hypertensive patient. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rautaharju PM, Park LP, Gottdiener JS, Siscovick D, Boineau R, Smith V, Powe NR. Race‐ and sex‐specific ECG models for left ventricular mass in older populations. Factors influencing overestimation of left ventricular hypertrophy prevalence by ECG criteria in African‐Americans. J Electrocardiol. 2000;33:205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spencer CG, Beevers DG, Lip GY. Ethnic differences in left ventricular size and the prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy among hypertensive patients vary with electrocardiographic criteria. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malan L, Hamer M, Schlaich MP, Lambert GW, Harvey BH, Reimann M, Ziemssen T, de Geus EJ, Huisman HW, van Rooyen JM, Schutte R, Schutte AE, Fourie CM, Seedat YK, Malan NT. Facilitated defensive coping, silent ischaemia and ECG left‐ventricular hypertrophy: the SABPA study. J Hypertens. 2012;30:543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Okin PM, Wright JT, Nieminen MS, Jern S, Taylor AL, Phillips R, Papademetriou V, Clark LT, Ofili EO, Randall OS, Oikarinen L, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, Julius S, Dahlof B, Devereux RB. Ethnic differences in electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy: the LIFE study. Losartan Intervention For Endpoint. Am J Hypertens. 2002;15:663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mathew J, Sleight P, Lonn E, Johnstone D, Pogue J, Yi Q, Bosch J, Sussex B, Probstfield J, Yusuf S. Reduction of cardiovascular risk by regression of electrocardiographic markers of left ventricular hypertrophy by the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor ramipril. Circulation. 2001;104:1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Nieminen MS, Snapinn S, Harris KE, Aurup P, Edelman JM, Wedel H, Lindholm LH, Dahlof B. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2004;292:2343–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santhanakrishnan R, Wang N, Larson MG, Magnani JM, Vasan RS, Wang TJ, Yap J, Feng L, Yap KB, Ong HY, Ng TP, Richards AM, Lam CS, Ho JE. Racial differences in electrocardiographic characteristics and prognostic significance in Whites versus Asians. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002956 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kizer JR, Arnett DK, Bella JN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Province MA, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Liu JE, Devereux RB. Differences in left ventricular structure between black and white hypertensive adults: the Hypertension Genetic Epidemiology Network study. Hypertension. 2004;43:1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Drazner MH, Dries DL, Peshock RM, Cooper RS, Klassen C, Kazi F, Willett D, Victor RG. Left ventricular hypertrophy is more prevalent in blacks than whites in the general population: the Dallas Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;46:124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Beevers G, de Faire U, Fyhrquist F, Ibsen H, Kristiansson K, Lederballe‐Pedersen O, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Omvik P, Oparil S, Wedel H. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schillaci G, Verdecchia P, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Guerrieri M, Zampi I, Battistelli M, Bartoccini C, Porcellati C. Improved electrocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:714–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vanezis AP, Bhopal R. Validity of electrocardiographic classification of left ventricular hypertrophy across adult ethnic groups with echocardiography as a standard. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41:404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Ascertainment of Study End Points and Chronic Dialysis

Table S2. Associations Between Time‐Dependent Cornell Voltage Product and Cardiovascular End Points Among Men

Table S3. Associations Between Time‐Dependent Cornell Voltage Product and Cardiovascular End Points Among Women

Table S4. Model Calibration, Discriminative Capacity, and Reclassification for Incident CVD (CHD+Ischemic Stroke) Including White and Black Men and Women (Cutoffs for PCE: <5%, 5% to <7.5%, 7.5 to <10%, and ≥10%)

Figure S1. Kaplan‐Meir curves of coronary heart disease (CHD; A), transient ischemic attack (TIA; B), ischemic stroke (C), hemorrhagic stroke (D), and heart failure (E).