Abstract

Background

Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) is an inflammatory cytokine implicated in plaque instability in acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We aimed to evaluate the prognostic implications of IL‐6 post‐ACS.

Methods and Results

IL‐6 concentration was assessed at baseline in 4939 subjects in SOLID‐TIMI 52 (Stabilization of Plaque Using Darapladib—Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 52), a randomized trial of darapladib in patients ≤30 days from ACS. Patients were followed for a median of 2.5 years for major adverse cardiovascular events; cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke) and cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization. Primary analyses were adjusted first for baseline characteristics, days from index ACS, ACS type, and randomized treatment arm. For every SD increase in IL‐6, there was a 10% higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (adjusted hazard ratio [adj HR] 1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01‐1.19) and a 22% higher risk of cardiovascular death or heart failure (adj HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.11‐1.34). Patients in the highest IL‐6 quartile had a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (adj HR Q4:Q1 1.57, 95% CI 1.22‐2.03) and cardiovascular death or heart failure (adj HR 2.29, 95% CI 1.6‐3.29). After further adjustment for biomarkers (high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 activity, high‐sensitivity troponin I, and B‐type natriuretic peptide), IL‐6 remained significantly associated with the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (adj HR Q4:Q1 1.43, 95% CI 1.09‐1.88) and cardiovascular death or heart failure (adj HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.22‐2.63).

Conclusions

In patients after ACS, IL‐6 concentration is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes independent of established risk predictors and biomarkers. These findings lend support to the concept of IL‐6 as a potential therapeutic target in patients with unstable ischemic heart disease.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, atherosclerosis, biomarker, inflammation, vascular biology

Subject Categories: Inflammation, Biomarkers, Coronary Circulation

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) is an inflammatory cytokine implicated in plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. However, it's prognostic relevance in patients after an acute coronary syndrome has remained unclear.

We determined that IL‐6 is associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events including heart failure.

This relationship was independent of established clinical predictors and risk markers including hsCRP, Lp‐PLA2 activity, hsTnI, and BNP.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The inflammatory cytokine IL‐6 may be useful for risk stratification in patients after an acute coronary syndrome.

These findings lend support to studies that are investigating a possible role for interleukin‐6 as a therapeutic target in patients with unstable coronary artery disease.

Introduction

Initiation and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis to plaque instability and rupture in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) comprise a complex process driven by both vascular lipoprotein accumulation and inflammation.1 Interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) is a cytokine that has been implicated in vascular inflammation2 and the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis and degradation of the fibrous cap contributing to plaque instability.3, 4 IL‐6 propagates inflammation and promotes hepatic hs‐CRP (high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein) production. Prior studies have demonstrated that higher concentrations of IL‐6 are associated with worse vascular health in individuals without clinical atherosclerosis and are associated with the risk of future myocardial infarction (MI).5, 6 In patients with ST‐elevation MI (STEMI), IL‐6 has been shown to be upregulated at the site of coronary occlusion.7, 8 It has also been suggested that IL‐6 concentration may be useful for identifying those patients with unstable coronary disease who may benefit more from an invasive strategy.9

Interest in IL‐6 as a potential therapeutic target is supported by Mendelian randomization studies that have shown signaling through the IL‐6 receptor to be directly implicated in the development of coronary heart disease.10 Moreover, blockade of the IL‐6 receptor with tocilizumab has been shown to attenuate inflammation and blunt the periprocedural rise in troponin in patients with non‐ST‐elevation MI.11 However, the relationship of IL‐6 with outcomes in patients after ACS remains incompletely defined. This relationship remains of importance because of interest in the IL‐1/IL‐6/CRP axis as a potential therapeutic target.11, 12 As an exploratory analysis, we therefore evaluated the association of IL‐6 with cardiovascular outcomes in a large randomized trial population of an anti‐inflammatory therapeutic in patients after ACS.

Methods and Materials

Study Population

The SOLID‐TIMI 52 (Stabilization of Plaque Using Darapladib‐Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 52) study design and trial results have been previously published.13, 14 In brief, the trial population enrolled 13 026 moderate‐ to high‐risk patients across 36 countries within 30 days of hospitalization with an ACS (unstable angina, non‐ST‐elevation MI , or STEMI). Patients were randomly allocated to once‐daily oral darapladib (an inhibitor of the proinflammatory enzyme lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2) or matching placebo in a double‐blinded manner. The use of guideline‐recommended therapies was strongly encouraged throughout the duration of the trial through the routine distribution of performance reports to sites and country leaders. The median duration of follow‐up was 2.5 years.

Biomarker and Chemistry Assessment

Serum and plasma samples were collected at baseline in randomly selected patients and stored at −20°C or colder for less than 6 weeks and then shipped on dry ice to the TIMI Clinical Trials Laboratory where they were then stored at −70°C or colder. Routine blood chemistries and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 activity (diaDexus, Poway, CA) were assessed in all patients at baseline (median 14 days after ACS). Each of the following biomarkers were also assayed in a randomly selected, planned cohort of ≈5000 patients: IL‐6 (Erenna Immunoassay, Singulex, Inc, Palo Alto, CA), high‐sensitivity troponin I (hsTnI) and B‐type natriuretic peptide (BNP, Architect i2000SR; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), and hsCRP (cobas 6000; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

End Point Assessment

The primary end point for the trial was the composite of coronary heart disease death, MI, or urgent coronary revascularization for myocardial ischemia (major coronary events). Prespecified end points of interest for this analysis included the composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (major adverse cardiovascular events, MACE), and the composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (HF). Individual components of the composite end points were also assessed. All events in this analysis were adjudicated by a blinded Clinical Events Committee.

Statistical Methods

Baseline characteristics were examined by IL‐6 quartiles. Multilevel and single‐level categorical variables were assessed by χ2 and Cochran Armitage trend tests, respectively, and continuous variables with the Jonckheere‐Terpstra test. The correlation between IL‐6 and established biomarkers was evaluated with the Spearman correlation test. Median concentrations of IL‐6 were compared with the Kruskal‐Wallis test in those with and without the outcomes of interest. Kaplan‐Meier rates are reported at 3 years. As a sensitivity analysis, a landmark analysis was performed beyond 30 days in order to assess the long‐term association of IL‐6 with recurrent cardiovascular events following the early inflammatory response after ACS.

The risk of cardiovascular outcomes associated with IL‐6 quartiles and log‐transformed IL‐6 concentration was examined with Cox proportional hazards modeling. The generated hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were adjusted for age, sex, race (white versus nonwhite), smoking status, diabetes mellitus, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, baseline low‐density lipoprotein levels, prior MI, prior percutaneous coronary intervention, index event (ST‐elevation ACS or STEMI versus non‐ST‐elevation ACS), days from index event, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, peripheral artery disease, and randomized treatment arm. Of 4939 patients in the biomarker substudy, 4720 (96%) had complete data available for multivariate analysis. The model was subsequently adjusted for established biomarkers, including hsTnI, hsCRP, lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 and BNP. A sensitivity analysis was conducted that included left ventricular ejection fraction in the model (available in 84.1% of study population). The interaction between IL‐6 and the treatment benefit of darapladib was examined by including an interaction term in the models. An additional sensitivity analysis was stratified by index diagnosis (NSTE‐ACS and STEMI). This was an observational study from a randomized clinical trial cohort. Because this analysis was exploratory, no formal adjustments for multiplicity were performed.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the randomly selected biomarker cohort (n=4939) versus the overall trial population are shown in Table S1. The median baseline IL‐6 concentration was 2.02 pg/mL (25th and 75th percentiles 1.16 and 3.97 pg/mL, respectively) when assessed a median of 14 days from the qualifying ACS event. No samples had IL‐6 values below the lowest detectable level of 0.158 pg/mL.

In general, higher concentrations of IL‐6 were associated with female sex, white race, current smoking, diminished renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2), peripheral artery disease, and more diseased coronary vessels at catheterization. Patients with higher concentrations of IL‐6 were significantly more likely to have STEMI as their index event and to have been enrolled in Western or Eastern Europe. Lower IL‐6 concentrations were associated with hyperlipidemia and prior MI (Table 1). The use of evidence‐based therapies was high across groups and the use of statins, aspirin, β‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor blockers at baseline did not significantly vary across IL‐6 quartiles. However, patients with higher IL‐6 concentrations were significantly more likely to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention for the qualifying event and be on a P2Y12 inhibitor. There were modest to strong correlations between IL‐6 and hsTnI (r=0.48, P<0.001) and hsCRP (r=0.71, P<0.001), and a weaker correlation between IL‐6 and BNP (r=0.24, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics Stratified by IL‐6 Quartile

| Baseline Characteristic | N (%) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (≤1.16 pg/mL) N=1236 | Quartile 2 (1.16‐2.02 pg/mL) N=1236 | Quartile 3 (2.02‐3.97 pg/mL) N=1233 | Quartile 4 (>3.97 pg/mL) N=1234 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 63 (57, 69) | 65 (60, 71) | 64 (59, 71) | 65 (60, 72) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 26.9 (25.1, 30.1) | 28.1 (25.1, 31.8) | 28.2 (25.3, 31.6) | 27.7 (25.1, 31.2) | <0.001 |

| Female | 287 (23.2) | 324 (26.2) | 319 (25.9) | 345 (28.0) | 0.013 |

| Race | 0.013 | ||||

| White | 1064 (86.1) | 1082 (87.5) | 1103 (89.5) | 1094 (88.7) | |

| Black | 28 (2.3) | 29 (2.3) | 32 (2.6) | 37 (3.0) | |

| Asian | 128 (10.4) | 98 (7.9) | 84 (6.8) | 83 (6.7) | |

| Other | 16 (1.3) | 27 (2.2) | 14 (1.1) | 20 (1.6) | |

| Region | <0.001 | ||||

| North America | 352 (28.5) | 302 (24.4) | 250 (20.3) | 215 (17.4) | |

| South America | 91 (7.4) | 108 (8.7) | 105 (8.5) | 88 (7.1) | |

| Western Europe | 316 (25.6) | 339 (27.4) | 386 (31.3) | 448 (36.3) | |

| Eastern Europe | 346 (28.0) | 376 (30.4) | 397 (32.2) | 370 (30.0) | |

| Asian Pacific | 131 (10.6) | 111 (9.0) | 95 (7.7) | 113 (9.2) | |

| Current smoker | 161 (13.0) | 203 (16.4) | 267 (21.7) | 275 (22.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 878 (71.0) | 929 (75.2) | 935 (75.8) | 916 (74.2) | 0.066 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 840 (68.0) | 827 (66.9) | 813 (65.9) | 755 (61.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 379 (30.7) | 419 (33.9) | 456 (37.0) | 416 (33.7) | 0.042 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 93 (7.6) | 131 (10.7) | 168 (13.9) | 194 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| History of PAD | 82 (6.6) | 120 (9.7) | 100 (8.1) | 136 (11.0) | 0.001 |

| Prior MI | 423 (34.2) | 401 (32.4) | 368 (29.8) | 363 (29.4) | 0.004 |

| Prior PCI | 320 (25.9) | 304 (24.6) | 292 (23.7) | 249 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Qualifying event | |||||

| STEMI | 475 (38.4) | 522 (42.2) | 576 (46.7) | 669 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| UA | 198 (16.0) | 165 (13.3) | 129 (10.5) | 101 (8.2) | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI | 563 (46.0) | 549 (44.4) | 528 (42.8) | 464 (37.6) | <0.001 |

| Days from event | 20 (13, 26) | 17 (9, 24) | 12 (5, 21) | 6 (3, 13) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 915 (74.0) | 918 (74.3) | 928 (75.3) | 990 (80.2) | <0.001 |

| Fibrinolytics | 113 (9.1) | 103 (8.3) | 108 (8.8) | 117 (9.5) | 0.70 |

| CAD anatomy | <0.003 | ||||

| One‐vessel | 505 (48.4) | 474 (46.3) | 424 (40.5) | 445 (41.0) | |

| Two‐vessel | 293 (28.1) | 300 (29.3) | 348 (33.3) | 357 (32.9) | |

| Three‐vessel | 245 (23.5) | 249 (24.3) | 274 (26.2) | 284 (26.2) | |

| Medications | |||||

| Aspirin | 1205 (97.5) | 1175 (95.1) | 1196 (97.0) | 1199 (97.2) | 0.68 |

| P2Y12 Inhibitor | 1086 (87.9) | 1066 (86.2) | 1090 (88.4) | 1125 (91.2) | 0.003 |

| β‐Blocker | 1059 (85.7) | 1099 (88.9) | 1101 (89.3) | 1086 (88.0) | 0.075 |

| ACEI or ARB | 994 (80.4) | 1049 (84.9) | 1027 (83.3) | 1036 (84.0) | 0.058 |

| Statin | 1171 (94.7) | 1160 (93.9) | 1178 (95.5) | 1173 (95.1) | 0.35 |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate in mL/min per 1.73 m2; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non‐ST‐elevation MI; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐elevation MI; UA, unstable angina.

*Continuous variables are presented as medians (interquartile range) and categorical as numbers (percentages).

IL‐6 Concentration and Risk of Cardiovascular Events

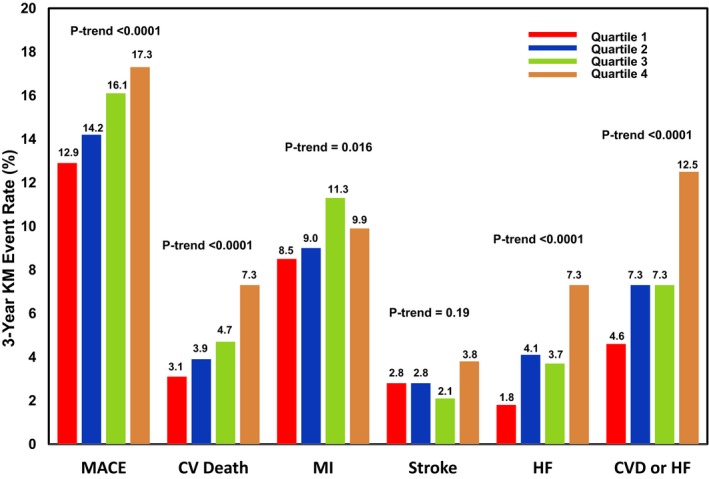

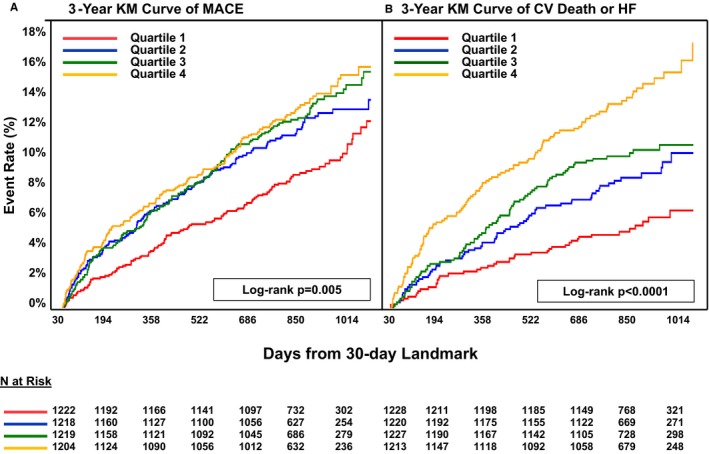

Median IL‐6 concentrations were significantly higher for patients who subsequently experienced MACE, cardiovascular death or HF, and individual components during long‐term follow‐up, compared with patients without an event (Table 2). A stepwise increase in the risk of MACE was seen across quartiles of IL‐6 (P trend<0.0001; Figure 1), including the individual components of cardiovascular death (P trend <0.0001) and MI (P trend=0.016) but not stroke (P trend=0.19). Similarly, a stepwise increase in the risk of cardiovascular death or HF (P trend <0.0001) and its components was seen with increasing IL‐6 concentration (Figure 1). A landmark analysis demonstrated consistency of these findings when the analysis period was restricted to beyond 30 days following randomization (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Median IL‐6 Concentration by Long‐Term Cardiovascular End Points

| End Point | N (%) N=4939 | Median IL‐6 Level (IQR), pg/mL | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Event | With Event | |||

| MACE | 644 (13.0) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death or HF | 342 (6.9) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.7 (1.5, 5.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 204 (4.1) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.8 (1.5, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 401 (8.1) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.2) | 0.03 |

| Stroke | 117 (2.3) | 2.0 (1.2, 3.9) | 2.2 (1.3, 4.3) | 0.4 |

| HF hospitalization | 182 (3.7) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.9) | 2.9 (1.6, 6.0) | <0.001 |

HF indicates heart failure; IQR, interquartile range; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

Figure 1.

Cumulative 3‐year Kaplan‐Meier event rates for major cardiovascular end points by IL‐6 quartile. CV indicates cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular death; HF, heart failure; KM, Kaplan‐Meier; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier 30‐day landmark analysis for MACE (A) and for cardiovascular death or HF (B) by IL‐6 quartiles. CV indicates cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; KM, Kaplan‐Meier; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death, MI or stroke; MI, myocardial infarction.

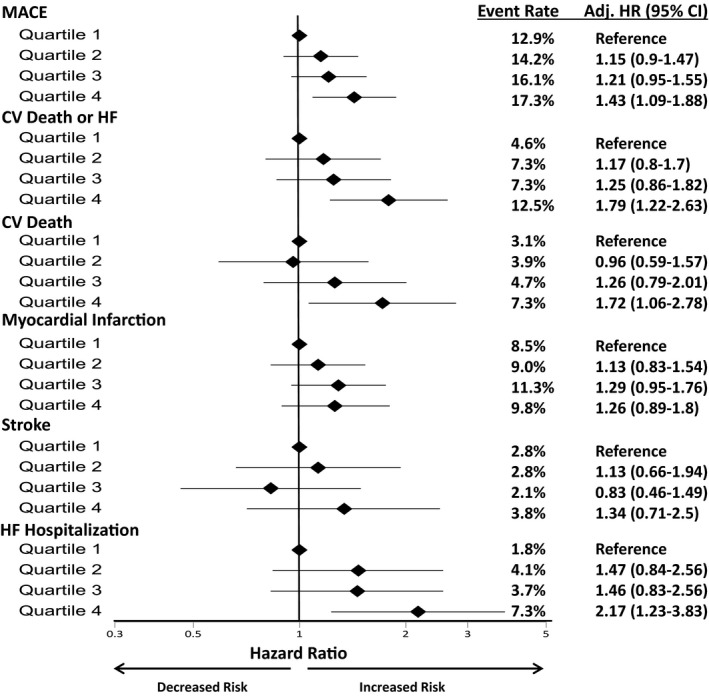

After adjusting for baseline characteristics and clinical predictors, there was a 10% higher risk of MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [adj HR] 1.10, 95% CI 1.01‐1.19), 24% higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) death (adj HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.09‐1.41), and a 22% higher risk of cardiovascular death or HF (adj HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.11‐1.34) for each SD increase in log‐transformed IL‐6. Patients with the highest IL‐6 concentrations had a 57% higher risk of MACE (adj HR Q4:Q1 1.57, 95% CI 1.22‐2.03), more than 2‐fold higher risk of cardiovascular death or HF (adj HR 2.29, 95% CI 1.6‐3.29) as well as a higher risk of cardiovascular death (adj HR 2.13, 95% CI 1.35‐3.36), MI (adj HR 1.39, 95% 1.01‐1.93) and HF (adj HR 3.1, 95% CI 1.81‐5.33) (Table 3). After further adjustment for established markers (hsCRP, BNP, hsTnI, and lipoprotein‐associated phospholipase A2 activity), IL‐6 remained significantly associated with the risk of MACE (adj HR Q4:Q1 1.43, 95% CI 1.09‐1.88) and cardiovascular death or HF (adj HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.22‐2.63) (Figure 3). In the subset of patients who had an assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction during their index hospitalization, inclusion of this factor in multivariable models yielded similar results (Table S2). Directionally consistent results were observed across both the STEMI and non‐ST‐elevation ACS populations (Tables S3 and S4, Figures S1 and S2). The magnitude of the relationship between IL‐6 and cardiovascular outcomes appeared to be stronger in STEMI than in non‐ST‐elevation ACS patients (MACE, P interaction=0.05; cardiovascular death or HF, P interaction=0.001). Overall, the investigational therapy darapladib did not reduce the primary outcome of CHD death, MI, or urgent coronary revascularization for myocardial ischemia (HR 1.0, 95% CI 0.91‐1.09). Consistent with the overall trial results, IL‐6 concentration did not identify patients who benefited from darapladib (P‐value for interaction=0.57).

Table 3.

Risk of Cardiovascular Events by IL‐6 Quartile Concentration After Adjustment for Clinical Factors

| End Point | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 2 (N=1192) | Quartile 3 (N=1177) | Quartile 4 (N=1168) | ||

| MACE | 1.22 (0.96‐1.55) | 1.29 (1.01‐1.65) | 1.57 (1.22‐2.03) | 0.0005 |

| Cardiovascular death/HF | 1.37 (0.95‐1.98) | 1.4 (0.96‐2.02) | 2.29 (1.6‐3.29) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 1.14 (0.71‐1.84) | 1.4 (0.88‐2.23) | 2.13 (1.35‐3.36) | 0.0009 |

| MI | 1.18 (0.87‐1.59) | 1.37 (1.01‐1.85) | 1.39 (1.01‐1.93) | 0.029 |

| Stroke | 1.17 (0.68‐2.0) | 0.92 (0.52‐1.64) | 1.51 (0.85‐2.67) | 0.28 |

| HF hosp | 1.77 (1.02‐3.07) | 1.66 (0.95‐2.9) | 3.1 (1.81‐5.33) | <0.0001 |

Model adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, body mass index, race (white vs nonwhite), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peripheral artery disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, hyperlipidemia, prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, index qualifying event (ST‐elevation MI vs non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome), days from qualifying event, randomized treatment arm, LDL‐cholesterol. HF indicates heart failure; hosp, hospitalization; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke; MI, myocardial infarction.

*Quartile 1 as reference group by Cox Proportional Hazard analysis.

Figure 3.

Association of baseline IL‐6 quartile with cardiovascular end points after further adjustment with biomarkers. Adj HR indicates adjusted hazard ratio; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; KM, Kaplan‐Meier; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events including cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke. Model adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, body mass index, race (white vs nonwhite), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, peripheral artery disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, hyperlipidemia, prior myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, index qualifying event (ST‐elevation ACS vs non‐ST elevation ACS), days from qualifying event, randomized treatment arm, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protrin, lipoprotein‐related phospholipase A2, high‐sensitivity troponin I, and B‐type natriuretic peptide.

Discussion

Our findings from this exploratory analysis within the SOLID‐TIMI 52 trial demonstrated that in a cohort of patients post‐ACS, IL‐6 is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events, including recurrent MI, HF, and death, independent of traditional clinical risk factors and known biomarkers, such as hsCRP, associated with vascular disease. This heightened risk emerged early after ACS by 30 days and persisted through a median 2.5 years of follow‐up.

IL‐6 and Cardiovascular Risk

The baseline median IL‐6 concentration in our ACS population was 2.01 pg/mL, which can be compared to a value of 1.46 in a relatively healthy cohort of men without established coronary disease.5 IL‐6 has been independently linked to endothelial dysfunction and subclinical atherosclerosis after adjustment for baseline hsCRP15 and has been shown to be an important predictor of vascular events in patients without clinically evident atherosclerosis at baseline.5, 6 The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration meta‐analysis pooled data from up to 29 cohorts without established coronary artery disease but with risk factors and demonstrated that for each SD increase in log‐IL‐6, there is a 25% increased risk for incident CHD including CHD death.16 We showed in patients with established CHD, after adjusting for additional clinical risk factors and other inflammatory biomarkers, that the risk of CHD death per SD increase in log‐IL‐6 was similar.

Compared to its state during stable progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, the inflammatory cascade is enhanced following ACS.17 Progressive atherosclerosis involves the recruitment and differentiation of monocytes within the blood vessel wall, developing into lipid‐laden proinflammatory foam cells.17 When these cells subsequently undergo cell death, they cause a large necrotic lipid core and release of IL‐6 and other cytokines, which is implicated in the destruction of its fibrous cap and plaque instability that leads to ACS.17 In the Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease Trial, elevated hsCRP was additive to troponin T levels in its predictive risk of long‐term mortality in patients with unstable coronary artery disease.18 Similarly, hsCRP was an independent predictor of poor outcomes post‐ACS in the TIMI 11A Trial.19 However, the synthesis of hsCRP is secondary to upstream interleukin cytokine stimulation in the inflammatory process.

Concurrently elevated IL‐6, hsCRP, and NT‐proBNP were found to be independent predictors of 90‐day death, shock, or heart failure in patients with STEMI in an APEX‐AMI subgroup analysis.20 The Fragmin and Fast Revascularization during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease II trial demonstrated an absolute reduction of 5.1% in mortality seen with an early invasive strategy in those with IL‐6 concentrations greater than 5 ng/L but no detectable benefit in patients with lower concentrations.9 In the current study, the magnitude of the relationship between IL‐6 and cardiovascular outcomes appeared to be stronger in STEMI than in non‐ST‐elevation ACS patients, which may in part suggest that IL‐6 reflects the influence of infarct size. However, we demonstrated that these relationships remained significant when index diagnosis, management strategy, and left ventricular ejection fraction were considered in multivariate models. Further, IL‐6 was prognostic beyond the acute phase of the event and was associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes through long‐term follow‐up. This suggests that IL‐6 may have additional predictive value downstream from the initial infarct. In post‐MI patients the inflammatory cascade has been implicated in altering the coronary vasculature in a diffuse way, leading to subsequent plaque instability at nonculprit atherosclerotic lesions and contributing to a risk of reinfarction and poor cardiovascular outcomes.21, 22, 23

Our study also demonstrated that the highest IL‐6 quartile was associated with more than 2‐fold increased risk of HF hospitalization compared to the lowest IL‐6 quartiles. IL‐6 is an inducer of matrix metalloproteinase expression,24 a protein family involved in the upregulation of collagen synthesis, resulting in progressive fibrosis and cardiac remodeling known to contribute to the mechanism of heart failure.25 In addition, with progression of nonculprit atherosclerosis post‐ACS, an increase in diastolic dysfunction is likely to accompany ongoing multivessel ischemia. Our study demonstrated that despite its association with the risk of HF hospitalization, IL‐6 concentration was only weakly correlated with BNP. There was no difference in the use of traditional HF therapies across IL‐6 quartiles, such as β‐blockers or angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or aldosterone receptor blockers, and therefore, results cannot be explained by an imbalance in optimal medical therapy.

IL‐6 as a Possible Therapeutic Target

Although the hypothesis can only be confirmed through a clinical trial, the findings in the present study support the concept of IL‐6 as a potential therapeutic target in ACS. Tocilizumab, a humanized anti‐IL‐6 receptor antibody, is currently under study. The ENTRACTE trial is analyzing the effects of tocilizumab versus etanercept on the risk of vascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a history of CHD (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01331837). In phase 2 testing, tocilizumab reduced CRP and demonstrated a trend toward troponin T reduction in patients with non‐ST‐elevation MI,11 and in a recent community‐based study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis has been demonstrated to improve endothelial function.26 Methotrexate, an anti‐inflammatory therapeutic agent used in inflammatory arthritis and inhibitor of the central IL‐1/IL‐6/CRP axis, is currently under study in CIRT (the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial), in which patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome and known coronary disease are randomized to low‐dose methotrexate or placebo and followed for MACE.27 Last, the recent CANTOS trial (the Canakinumab Anti‐Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) studied cardiovascular outcomes in stable coronary artery disease patients with persistently elevated hsCRP (>2 mg/L) randomized to placebo or canakinumab, an IL‐1β inhibitor with upstream effects on IL‐6.12 Results demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events with canakinumab. Prior to this positive trial, however, effective anti‐inflammatory therapeutics designed to reduce cardiovascular events have remained elusive. To that end, the p38 MAP‐kinase inhibitor losmapimod did not improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with ACS28 despite favorable effects on IL‐6 and hsCRP.28, 29 As a result, challenges continue to exist with identifying meaningful surrogate end points during the development of anti‐inflammatory therapeutics.

Limitations

This study has limitations that warrant consideration. By design, the SOLID‐TIMI 52 trial enrolled patients throughout the first 30 days post‐ACS (median 14 days), and it would be expected that IL‐6 concentration would rise acutely at the time of qualifying event, and may correlate with the size of the infarct. Left ventricular function was not assessed in all patients and therefore could not be adjusted for in all models. However, the observed association between IL‐6 and cardiovascular risk remained significant after adjustment for time from the index event as well as the type of ACS and other surrogates of infarct size. Further, the observed results persisted when events during the first 30 days after ACS were excluded. Although Mendelian randomization studies suggest a causal role for IL‐6 in atherogenesis, the value of IL‐6 as a therapeutic target can only be confirmed through clinical trials of IL‐6 blockade designed specifically to test the hypothesis. As with any observational analysis, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. Moreover, cut points employed in the current study will require prospective validation.

Conclusions

In patients after ACS, IL‐6 concentration is significantly associated with the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes independent of established risk predictors and established biomarkers. Ongoing need exists for clinical trials that target inflammation through IL‐6–related pathways, some of which are now under way in patients with a history of stable coronary disease. Further study is warranted in patients with unstable coronary disease patients to mitigate the progression of culprit and nonculprit disease and improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Sources of Funding

The SOLID‐TIMI 52 trial was supported by a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline. Reagent support was provided by Singulex (IL‐6) and Abbott Laboratories (hsTnI, BNP).

Disclosures

Dr Morrow reports grants to the TIMI Study Group from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Singulex, and consultant fees from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, diaDexus, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Peloton, Roche Diagnostics, and Verseon. Dr Cannon reports research grants from Amgen, Arisaph, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda, and consulting fees from Alnylam, Amgen, Arisaph, AstraZeneca, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Kowa, Lipimedix, Merck, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Takeda. Dr Jarolim has received research support through his institution from Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Daiichi‐Sankyo, Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, Merck, Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Takeda Global Research and Development Center, and Waters Technologies Corporation. Dr Lukas is an employee at GlaxoSmithKline. Dr Hochman is principal investigator for the ISCHEMIA trial for which, in addition to support by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, there are in‐kind donations from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Inc, St Jude Medical, Inc, Volcano Corporation, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Omron Healthcare, Inc, and financial donations from Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals. Dr Braunwald reports grant support to his institution from GlaxoSmithKline. For work outside the submitted work, Dr Braunwald reports grant support to his institution from Duke University, Merck, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Daiichi Sankyo; personal fees for consultancies with The Medicines Company and Theravance; personal fees for lectures from Medscape and Menarini International; uncompensated consultancies and lectures from Merck and Novartis. Dr O'Donoghue reports research grants from Amgen, the Medicines Company, AstraZeneca, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Janssen. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics in Biomarker Population of SOLID‐TIMI 52

Table S2. Association of Baseline IL‐6 Quartile With Cardiovascular End Points After Further Adjustment for Left Ventricular Dysfunction

Table S3. Adjusted Risk of Cardiovascular End Points by Baseline IL‐6 Quartile in NSTE ACS Population Only

Table S4. Adjusted Risk of Cardiovascular End Points by Baseline IL‐6 Quartile in STEMI Population Only

Figure S1. Unadjusted 3‐year Kaplan‐Meier Event rates of cardiovascular end points by baseline IL‐6 quartile in NSTE‐ACS population only.

Figure S2. Unadjusted 3‐year Kaplan‐Meier event rates of cardiovascular end points by baseline IL‐6 quartile in STEMI population only.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005637 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005637.)

References

- 1. Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin‐6 and the acute phase response. Biochem J. 1990;265:621–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yudkin JS, Kumari M, Humphries SE, Mohamed‐Ali V. Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: is interleukin‐6 the link? Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schieffer B, Selle T, Hilfiker A, Hilfiker‐Kleiner D, Grote K, Tietge UJ, Trautwein C, Luchtefeld M, Schmittkamp C, Heeneman S, Daemen MJ, Drexler H. Impact of interleukin‐6 on plaque development and morphology in experimental atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:3493–3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer M, Hennekens C. Plasma concentration of interleukin‐6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C‐reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maier W, Altwegg LA, Corti R, Gay S, Hersberger M, Maly FE, Sutsch G, Roffi M, Neidhart M, Eberli FR, Tanner FC, Gobbi S, von Eckardstein A, Luscher TF. Inflammatory markers at the site of ruptured plaque in acute myocardial infarction: locally increased interleukin‐6 and serum amyloid A but decreased C‐reactive protein. Circulation. 2005;111:1355–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ammirati E, Cannistraci CV, Cristell NA, Vecchio V, Palini AG, Tornavall P, Paganoni AM, Miendlarzewska EA, Sangalli LM, Monello A, Pernow J, Bjornstedt Bennermo M, Marenzi G, Hu D, Uren NG, Cianflone D, Ravasi T, Manfredi AA, Maseri A. Identification and predictive value of interleukin‐6+ interleukin‐10+ and interleukin‐6– interleukin‐10+ cytokine patterns in ST‐elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;111:1336–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindmark E, Diderholm E, Wallentin L, Sigbahn A. Relationship between interleukin 6 and mortality in patients with unstable coronary artery disease: effects of an early invasive or noninvasive strategy. JAMA. 2001;286:2107–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. IL6R Genetics Consortium and Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration . Interleukin‐6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta‐analysis of 82 studies. Lancet. 2012;379:1205–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kleveland O, Kunszt G, Bratlie M, Ueland T, Broch K, Holte E, Michelsen AE, Bendz B, Amundsen BH, Espevik T, Aakhus S, Damas JK, Aukrust P, Wiseth R, Gullestad L. Effect of a single dose of the interleukin‐6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab on inflammation and troponin T release in patients with non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled phase 2 trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2406–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, Kastelein JJP, Cornel JH, Pais P, Pella D, Genest J, Cifkova R, Lorenzatti A, Forster T, Kobalava Z, Vida‐Simiti L, Flather M, Shimokawa H, Ogawa H, Dellborg M, Rossi PRF, Troquay RPT, Libby P, Glynn RJ. CANTOS Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2017; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, White HD, Serruys P, Steg PG, Hochman J, Maggioni AP, Bode C, Weaver D, Johnson JL, Cicconetti G, Lukas MA, Tarka E, Cannon CP. Study design and rationale for the Stabilization of pLaques usIng Darapladib‐Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (SOLID‐TIMI 52) trial in patients after an acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2011;162:613–619.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, White HD, Steen DP, Lukas MA, Tarka E, Steg PG, Hochman JS, Bode C, Maggioni AP, Im K, Shannon JB, Davies RY, Murphy SA, Crugnale SE, Wiviott SD, Bonaca MP, Watson DF, Weaver WD, Serruys PW, Cannon CP. Effect of darapladib on major coronary events after an acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2014;312:1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee W‐Y, Allison MA, Kim D‐J, Song C‐H, Barrett‐Connor E. Association of interleukin‐6 and C‐reactive protein with subclinical carotid atherosclerosis (the Rancho Bernardo Study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaptoge S, Seshasai SRK, Gao P, Freitag DF, Butterworth AS, Borglykke A, Di Angelantonio E, Gudnason V, Rumley A, Lowe GDO, Jørgensen T, Danesh J. Inflammatory cytokines and risk of coronary heart disease: new prospective study and updated meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:578–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindahl B, Toss H, Siegbahn A, Venge P, Wallentin L. Markers of myocardial damage and inflammation in relation to long‐term mortality in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during instability in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1139–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrow DA, Rifai N, Antman EM, Weiner DL, McCabe CH, Cannon CP, Braunwald E. C‐reactive protein is a potent predictor of mortality independently of and in combination with troponin T in acute coronary syndromes: a TIMI 11A substudy. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;7:1460–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Diepen S, Newby KL, Lopes RD, Stebbins A, Hasselblad V, James S, Roe MT, Ezekowitz JA, Moliterno DJ, Neumann F, Reist C, Mahaffey KW, Hochman JS, Hamm CW, Armstrong PW, Granger CB, Theroux P. Prognostic relevance of baseline pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory markers in STEMI: an APEX AMI substudy. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2127–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dutta P, Courties G, Wei Y, Leuschner F, Gorbatov R, Robbins CS, Iwamoto Y, Thompson B, Carlson AL, Heidt T, Majmudar MD, Lasitschka F, Etzrodt M, Waterman P, Waring MT, Chicoine AT, van der Laan AM, Niessen HWM, Piek JJ, Rubin BB, Butany J, Stone JR, Katus HA, Murphy SA, Morrow DA, Sabatine MS, Vinegoni C, Moskowitz MA, Pittet MJ, Libby P, Lin CP, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012;487:325–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goldstein JA, Demetriou D, Grines CL, Pica M, Shoukfeh M, O'Neill WW. Multiple complex coronary plaques in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS, Mehran R, McPherson J, Farhat N, Marso SP, Parise H, Templin B, White R, Zhang Z, Serruys PW; PROSPECT Investigators . A prospective natural‐history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kothari P, Pestana R, Mesraoua R, Elchaki R, Khan K, Dannenberg A, Falcone D. IL‐6‐mediated induction of matrix metalloproteinase‐9 is modulated by JAK‐dependent IL‐10 expression in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2014;192:349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polyakova V, Loeffler I, Hein S, Miyagawa S, Piotrowska I, Dammer S, Risteli J, Schaper J, Kostin S. Fibrosis in endstage human heart failure: severe changes in collagen metabolism and MMP/TIMP profiles. Int J Cardiol. 2011;151:18–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bacchiega BC, Bacchiega AB, Gomez Usnayo MJ, Bedirian R, Singh G, da Rocha Castelar Pinheiro G. Interleukin 6 inhibition and coronary artery disease in a high‐risk population: a prospective community‐based clinical study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005038 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Everett BM, Pradhan AD, Solomon DH, Paynter N, Macfadyen J, Zaharris E, Gupta M, Clearfield M, Libby P, Hasan AA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Rationale and Design of the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial: a test of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis. Am Heart J. 2013;166:199–207.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Donoghue ML, Glaser R, Cavender MA, Aylward PE, Bonaca MP, Budaj A, Davies RY, Dellborg M, Fox KA, Gutierrez JA, Hamm C, Kiss RG, Kovar F, Kuder JF, Im KA, Lepore JJ, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Ophuis TO, Parkhomenko A, Shannon JB, Spinar J, Tanguay JF, Ruda M, Steg PG, Theroux P, Wiviott SD, Laws I, Sabatine MS, Morrow DA. Effect of losmapimod on cardiovascular outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:1591–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Melloni C, Sprecher DL, Sarov‐Blat L, Patel MR, Heitner JF, Hamm CW, Aylward P, Tanguay JF, DeWinter RJ, Marber MS, Lerman A, Hasselblad V, Granger CB, Newby LK. The study of LoSmapimod treatment on inflammation and InfarCtSizE (SOLSTICE): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2012;164:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Baseline Characteristics in Biomarker Population of SOLID‐TIMI 52

Table S2. Association of Baseline IL‐6 Quartile With Cardiovascular End Points After Further Adjustment for Left Ventricular Dysfunction

Table S3. Adjusted Risk of Cardiovascular End Points by Baseline IL‐6 Quartile in NSTE ACS Population Only

Table S4. Adjusted Risk of Cardiovascular End Points by Baseline IL‐6 Quartile in STEMI Population Only

Figure S1. Unadjusted 3‐year Kaplan‐Meier Event rates of cardiovascular end points by baseline IL‐6 quartile in NSTE‐ACS population only.

Figure S2. Unadjusted 3‐year Kaplan‐Meier event rates of cardiovascular end points by baseline IL‐6 quartile in STEMI population only.