Abstract

Introduction

Increasing demands on healthcare systems mean that nurses are taking on more roles as physician extenders. Capsule endoscopy (CE) is a laborious procedure where specialist nurses could reduce physician workload and rationalise resource utilisation. The aim of this review and meta-analysis is to consolidate data on nurses' performance in small bowel CE (SBCE).

Materials and methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted for randomised controlled trials and comparative studies on nurses in SBCE reading compared to physicians. We examined the performance of nurses compared to SBCE-trained physicians.

Results

Sixteen relevant studies were identified, with 820 SBCE examinations involving 20 nurses. 11/16 studies reported the numbers of SBCE findings detected. Overall, the pooled proportion of all findings reported by physicians and nurses was 86%. Studies involving nurses with endoscopic experience showed a summative detection rate of 89%. 7/16 studies reported the number of videos where there was agreement between the nurse and physicians for overall findings/diagnosis. The overall proportion of videos with agreement was 68%. In studies where nurses had endoscopy experience, the proportion of videos with agreement was 71%.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis supports a more active role for nurses in SBCE reading. We suggest nurses can function as independent CE readers in general, given adequate training and formal credentialing.

Keywords: Capsule endoscopy, nurses, physician extenders, diagnostic test, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

Increasing demands on healthcare systems mean that nurses are taking on more roles as physician extenders; therefore, there is a growing overlap in several daily duties performed by physicians and nurses. Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that appropriately trained nurses can be complementary and equal to physicians in diagnostic gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.1–4 In the United Kingdom and Europe, nurse endoscopists are already routinely employed to perform GI endoscopy with results comparable to that of physicians and high patient satisfaction.5–8 A recent review by Verschuur et al. on the involvement of nurses in GI endoscopy found many studies reporting cost savings by employing nurses in diagnostic upper GI endoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy and capsule endoscopy (CE).1

The main use of CE in current practice is for minimally-invasive investigation of small bowel pathology; however, a CE procedure generates lengthy small bowel footage per examination, requiring an average of 45 min to review.9 Hence, CE is an area where nurses may be particularly useful. Studies have demonstrated that employing a nurse endoscopist to read or pre-read CE videos (i.e. to identify or select areas of pathology for further medical review) is cost-effective; nurse endoscopists achieve good agreement with physicians. In particular, a study by Niv and Niv calculated a cost reduction from US$573 to US$249 when a nurse endoscopist was employed to pre-read CE videos,10 whilst Bossa et al. calculated cost savings of 30% using nurses as CE pre-readers.11 At the core of CE reading is detection and interpretation of images of pathology as the CE procedure itself is rarely operator-dependent. Therefore, reading time varies highly between reporters and may be dependent on experience, taking anywhere from 30 to 90 min. In spite of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommendations for credentials in CE,12 there is a lack of structured CE training programmes to formally assess competency in CE reading.13

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is therefore to consolidate existing data on nurses' performance in CE, and to determine whether nurse endoscopists perform similarly to medical-trained personnel in this setting. For the purposes of this meta-analysis we have focused on nurses as CE readers as this is the group most commonly employed as physician extenders for this purpose.

Materials and methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted on 11 July 2016 using PubMed, Embase and Science Direct. Terms used were ‘nurse’, ‘reading’, ‘review’, ‘pre-reading’, ‘physician extenders’ AND ‘capsule endoscopy’. The search was performed with no limitations.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: randomised controlled trials and comparative studies, including conference abstracts, examining the performance of nurses in small bowel CE (SBCE) reading compared to physicians.

Exclusion criteria included: meta-analyses or systematic reviews, narrative reviews, opinion papers, editorials, case reports or series; studies using CE review aids such as QuickView; studies where the performance of the nurses did not have an adequate reference standard, i.e. an experienced or expert physician CE reader, for comparison. To ensure a valid reference standard (RS) for comparison, we defined ‘experienced’ physician CE readers as having read a minimum of 50 CE videos whereas ‘expert’ CE readers had read a minimum of 150 CEs; studies where the RS did not have such experience were excluded. Furthermore, author names and locations were compared between similar articles to ensure no duplication of results.

Primary selection was done based on title and abstract. The references of selected articles were cross-checked to ensure that other relevant studies were not missed. Further selection was then carried out by reading the full texts of identified articles. Each search was performed independently by two reviewers (AK, DY) who then discussed any discrepancies. Any difference(s) in opinion were resolved by consensus.

Data were extracted in a standardised extraction form (Microsoft Excel 2010, Microsoft®). Where information was missing from the selected studies, corresponding authors were contacted either to obtain the information or to ascertain that no further information could be provided for this analysis.

Methodological quality and potential bias of the included studies was evaluated by using the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS)-2 scale.14 The QUADAS tool enables reviewers to evaluate the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. For this review and analysis, the ‘index test’ was defined as CE reading done by nurses, while the ‘RS’ was CE reading by experienced or expert physicians or their consensus review.

Outcome measures were as follows: performance of the nurses compared to CE-trained physicians, measured as either the number of findings reported by the nurses compared to the physicians, or the number of CE videos read where there was agreement between the nurses and physicians.

Data on agreement between nurses and physicians were extracted, pooled, and analysed. Pooled results with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived by using the fixed-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) unless significant heterogeneity was detected, in which case, a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird) was used. We used the Q statistic of I2 to estimate the heterogeneity of individual studies contributing to the pooled estimate. This was to evaluate whether the differences across the studies were greater than expected by chance alone. A p-value < 0.05 suggests that the heterogeneity demonstrated was beyond what could be expected by chance alone. I2 describes the percentage of total variation across studies because of heterogeneity rather than chance and was also used as a measure to quantify the amount of heterogeneity. I2 values 30–60 % were considered to represent moderate heterogeneity, 50–90 % substantial heterogeneity and 75–100 % considerable heterogeneity.15 Forest plots were constructed for visual display of individual studies and pooled results. Publication bias was assessed via funnel plots, obtained by plotting the log[odds ratio] vs precision (1/standard error) of individual studies. The symmetry of the funnel plots was estimated using Egger's regression asymmetry test where p < 0.1 was taken to show evidence of asymmetry.16 Statistical analysis was performed using StatsDirect 3 (Cheshire, UK).

The effects of heterogeneity between studies were assessed using sensitivity analyses by analysing only those studies where the nurses had endoscopic experience, studies where only expert CE reader physicians were used as the standard of comparison, and only studies which had been published as full articles, which corresponded to studies at lower risk of bias on QUADAS-2 analysis.

Results

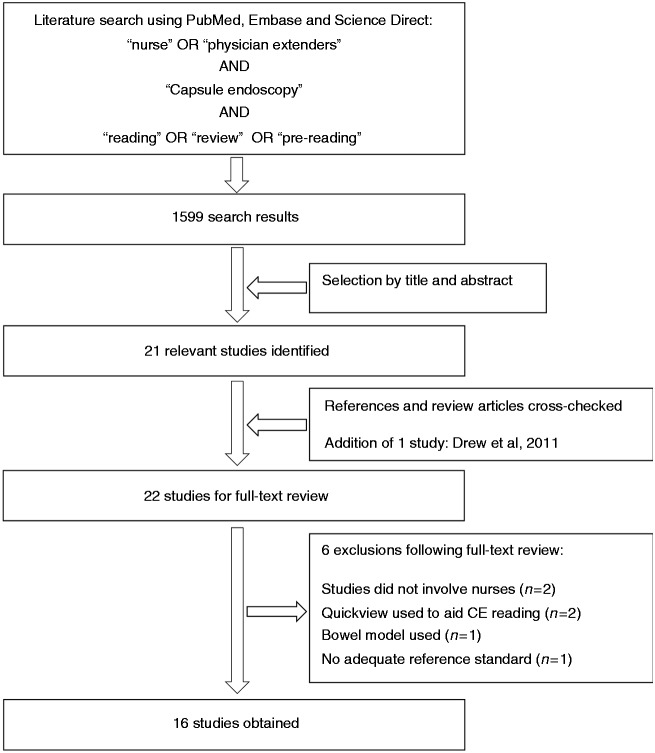

Figure 1 summarises the process of study selection. Using the above search strategy, 1599 studies were retrieved. Out of these, 21 studies were identified as relevant based on the titles and abstracts. Following cross-checking of the references of these relevant studies and related review articles, one more study was identified.17 Therefore, a total of 22 studies were included for further full-text review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram detailing process of study selection.

Six studies were excluded for the following reasons: two did not involve nurses;18,19 one used a bowel model instead of actual patients;20 two used QuickView to aid CE reading;21,22 and one did not have an adequate reference standard to gauge performance of the nurse endoscopist, as an inexperienced nurse was compared to a physician also inexperienced in CE.11

Study characteristics

Sixteen studies published from 2003 to 2015 were eventually included for review and meta-analysis.10,17,23–36 There were nine full papers,10,23,25,27,28,30,33–35 together with seven abstracts,17,24,26,29,31,32,36 with a total of 820 CE examinations involving 20 nurses. Table 1 summarises the included studies.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies.

| Authors, Yearref | No. of nurses | Nurse exp | Nurse CE training | Ref Standard (RS) | No. of CEs | CE indications | Nurse reading time, mins (mean±SD) | Physician reading time, mins (mean±SD) | Findings: SB angioectasias (nurse/ RS) | Findings: ulcers (nurse/ RS) | Findings: blood in lumen/ bleeding (nurse/ RS) | Findings: tumours (nurse/ RS) | Nurses' total findings | RS total findings | False positives/ over-reporting by nurses | Study agreement between nurses and RS (n/total CEs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoffman, 200329 (abst) | 1 | N End | NS | GE | 50 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 29 | NS | ||||

| Levinthal, 200330 | 1 | EN | 15 CEs, supervised | GE | 20 | NS | NS | NS | 25 | 27 | 3 | NS | ||||

| Friedland, 200436 (abst) | 1 | N End | CE course | Expert | 15 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 10/15 | ||||

| Niv, 200510 | 1 | GN | 15 CEs, supervised | Expert | 50 | OGIB: 27 CD/?CD: 7 Coeliac disease: 3 Lymphoma: 2 Nonspecific: 11 | 100 ± 13 | 59 ± 17 | 7/7 | 6/6 | 5/5 | 2/2 | 36 | 38 | 2 | NS |

| Ponferrada, 200532 (abst) | 1 | EN | NS | GE | 32 | NS | 138 ± 6 | 92 ± 9 | - | - | 6/6 | - | 11 | 11 | 1 | NS |

| Sidhu, 200735 | 1 | SN | None | GE | 50 | OGIB: 28 CD/?CD: 15 Nonspecific: 7 | 73 | 58 | NS | 190 | 260 | 235 | NS | |||

| Fernández-Urién, 200827 | 1 | EN | CE course | Consensus with expert | 20 | OGIB: 13 CD/?CD: 3 Nonspecific: 4 | 62.2 ± 19 | 51.9 ± 13.5 | 51/54 | 34/41 | 4/4 | - | 103 | 113 | 1 | 20/20 |

| Mussetto, 200831 (abst) | 2 | 1 EN, 1 SN | None | GE | 10 | NS | 110 (EN), 120 (SN) | 65 | NS | 17 (EN), 13 (SN) | 22 | NS | 7/10 (EN), 4/10 (SN) | |||

| Postgate, 200933 | 1 | EN | Own training prog. | Expert | 22 | OGIB: 26 CD/?CD: 17 Polyposis: 3 | NS | NS | 102 | 220 | 19 | 9/22 | ||||

| Riphaus, 200934 | 1 | EN | 15 CEs, supervised | Expert | 48 | OGIB: 36 CD/?CD: 7 Polyposis: 5 | 63 ± 26 | 54 ± 18 | 47/51 | 5/5 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 56 | 61 | NS | NS |

| Chandrasekhara, 201024 (abst) | 2 | 1 GN, 1 EN | NS | Expert | 20 | OGIB: 5 CD/?CD: 3 Nonspecific: 12 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 14/20 (GN), 10/20 (EN) | ||||

| Dokoutsidou, 201125 | 1 | EN | 50 CEs, supervised | Consensus with expert | 102 | OGIB: 76 CD/?CD: 7 Polyposis: 2 Coeliac disease: 8 Nonspecific: 9 | 117.3 ± 24.8 | 63.8 ± 8.5 | 24/26 | 6/6 | 9/9 | 3/3 | 105 | 113 | NS | NS |

| Drew, 201117 (abst) | 1 | N End with prior CE experience | >200 CEs | Consensus with 2 experts | 95 | OGIB: 80 CD/?CD: 5 Coeliac disease: 7 Nonspecific: 3 | 24 | 17 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 29 | 30 | NS | NS |

| Brock, 201223 | 1 | EN | CE course | GE | 220 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | 32 | 166/220 | ||||

| Dreanic, 201526 (abst) | 2 | ENs | NS | Experts | 20 | NS | 34.1 ± 4.1 | 34 ± 9.9 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 16/20 | |||

| Guarini, 201528 | 2 | ENs | CE course | Consensus with expert | 46 | OGIB: 37 CD/?CD: 3 Polyposis: 4 Nonspecific: 2 | 78 | 53 | 7/7 | - | 1/1 | 1/1 | 25 | 25 | 2 | NS |

Abbreviations: abst, abstract; CE, capsule endoscopy; NS, not specified; SD, standard deviation.

Nurse exp (nurse experience): EN, endoscopy nurse; N End, nurse endoscopist; GN, gastroenterology nurse; SN, staff nurse. RS (reference standard): GE gastroenterologist (i.e. moderate CE experience; not specified). CE indications: CD/?CD, Crohn's disease or suspected Crohn's disease; OGIB obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (both occult and overt), Nonspecific refers to indications such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea, suspected functional symptoms Findings: N, nurse; RS, reference standard.

Nurse experience

Of the 20 nurses, 13 were endoscopy nurses (involved in GI endoscopy, had seen and assisted in endoscopies but not performed endoscopies themselves), three were nurse endoscopists (deemed competent to perform GI endoscopy) of whom only one had CE experience, two were gastroenterology nurses (general gastroenterology, without specific GI endoscopy experience) and two were staff nurses (general nursing staff without specific gastroenterology or endoscopy experience).

Nurses' CE training

One of the nurses had had prior CE experience of over 200 CE videos. Five nurses had attended CE courses (1–2 days duration) prior to participating in their respective studies. Seven nurses were trained independently at the centres/departments conducting the studies. Out of these, 3/7 were trained using a programme of five demo videos and 10 supervised CE readings, 1/7 read 50 videos under supervision and 3/7 had no details specified about their training. Three of the nurses were not trained in CE reading before participating in the studies.

Reference standards (RS)

Nine of the 16 studies compared the nurses' performance to experienced/expert gastroenterologists (>150 CE).10,23,24,26,31–34,36 Three studies involved a general CE-trained gastroenterologist with moderate CE experience or no experience specified (minimum 50 CE).29,30,35 Four studies compared nurse performance against a consensus reached following discussion between the nurse and one or more experienced/expert physicians.17,25,27,28

Reported indications for CE

Indications included obscure GI bleeding (OGIB), both occult and overt (n = 328), investigation of Crohn's disease or suspected Crohn's disease (n = 67), investigation of coeliac disease (n = 18), investigation of polyposis syndromes (n = 14), lymphoma (n = 2), and other indications, mainly nonspecific symptoms such as diarrhoea and/or abdominal pain (n = 48).

Studies reporting outcomes as numbers of CE findings detected by RS and nurses

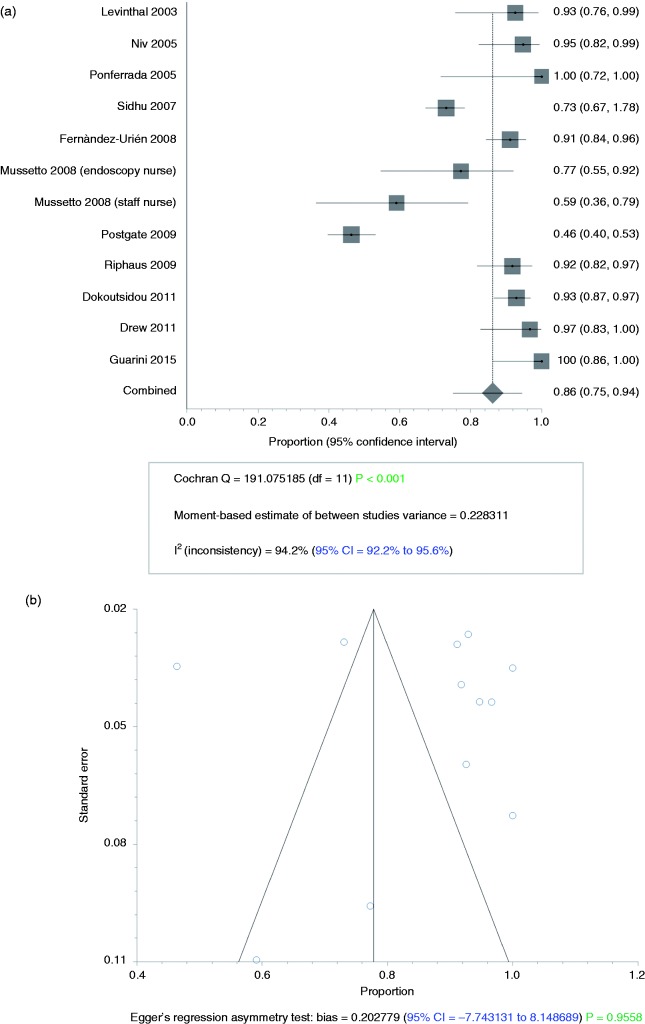

Eleven of the 16 studies reported outcomes using the numbers of CE findings reported,10,17,25,27,28,30–35 with 12 sets of data (two sets of data were obtained from one of the studies,31 as there were two nurses involved). The meta-analysis results for this outcome are summarised in Table 2. Overall, the pooled proportion of all types of findings reported by physicians and also reported by nurses was 0.86 (95% CI 0.75–0.94), i.e. the nurses picked up 86% of all CE findings reported by physicians trained in CE reading (Figure 2(a)). The random-effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (Q = 191.075, d.f.(Q) = 11, I2 = 94.2%, p < 0.0001) but there was no publication bias (p = 0.956) (Figure 2(b)).

Table 2.

Summary of meta-analysis results in studies reporting outcomes as numbers of CE findings detected by RS and nurses.

| Subgroup | Studies (n) | Nurses' findings (n) | RS findings (n) | Pooled proportion of nurses' findings compared to RS findings (95% CI) | I2 (heterogeneity) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 11 | 712 | 942 | 0.862 (0.750–0.945) | 94.2% (92.2–95.6%) |

| Full studies only | 8 | 642 | 857 | 0.869 (0.730–0.962) | 95.9% (94.4–96.9%) |

| Comparisons by type of CE findings | |||||

| Detection of angioectasias | 6 | 137 | 146 | 0.927 (0.880–0.963) | 0% (0–61%) |

| Detection of ulcers | 5 | 52 | 59 | 0.874 (0.780–0.944) | 0% (0–64.1%) |

| Detection of blood in lumen | 7 | 32 | 32 | 1.000 (0.865–1.000) | 0% (0–58.5%) |

| Comparisons between nurses and RS | |||||

| Nurses vs RS where expert CE readers were involved | 6 | 351 | 487 | 0.889 (0.677–0.995) | 96.7% (95.3–97.5%) |

| Nurses vs RS with only expert CE readers | 3 | 194 | 319 | 0.800 (0.412–0.997) | 97.5% (95.8–98.3%) |

| Nurses with GI endoscopy experience vs RS | 9 | 473 | 622 | 0.890 (0.740–0.980) | 95.4% (93.7–96.5%) |

| Nurses with no GI endoscopy experience vs RS | 3 | 239 | 320 | 0.774 (0.577–0.923) | 86.1% (35.9–93.6%) |

Abbreviations: CE, capsule endoscopy; CI, confidence interval; GI, gastrointestinal; n, number; RS, reference standard.

Figure 2.

(a) Forest plot showing pooled proportion of all capsule endoscopy findings determined by reference standard and picked up by nurse readers. (b) Funnel plot depicting publication bias for studies reporting proportion of all capsule endoscopy findings picked up by nurses.

The most commonly reported findings in our group of studies were angioectasias and ulcers. In the studies which reported angioectasias amongst their findings, the pooled proportion of angioectasias detected by nurses compared to physicians was 0.93 (95% CI 0.88–0.96). The pooled proportion of ulcers detected by nurses was 0.87 (95% CI 0.78–0.94). Notably, for blood in the lumen/ active bleeding, the third most common finding, there was complete agreement between the nurses and physicians.

When the nurses' performance was compared to RS involving expert CE readers (including those where the RS was reached by consensus), the nurses had a pooled detection rate of pathology of 0.89 (95% CI 0.68–0.99). In studies where only expert CE readers were used as the RS, the nurses had a pooled pathology detection rate of 0.80 (95% CI 0.41–1.00).

Studies involving only nurses with experience e in GI endoscopy (i.e. endoscopic nurses and nurse endoscopists) showed a summative detection rate of 0.89 of the physicians' findings (95% CI 0.74–0.98). Examining only the results from nurses with no endoscopic experience (i.e. general gastroenterology nurses and staff nurses), their pooled detection rate for CE findings was 0.77 of the physicians' findings (95% CI 0.58–0.92).

When only full studies were included, the pooled proportion of findings picked up by nurses compared to physicians was 0.87 (95% CI 0.73–0.96). The random effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (Q = 172.494, d.f.(Q) = 7, I2 = 95.9%, p < 0.0001) but there was no publication bias (p = 0.832).

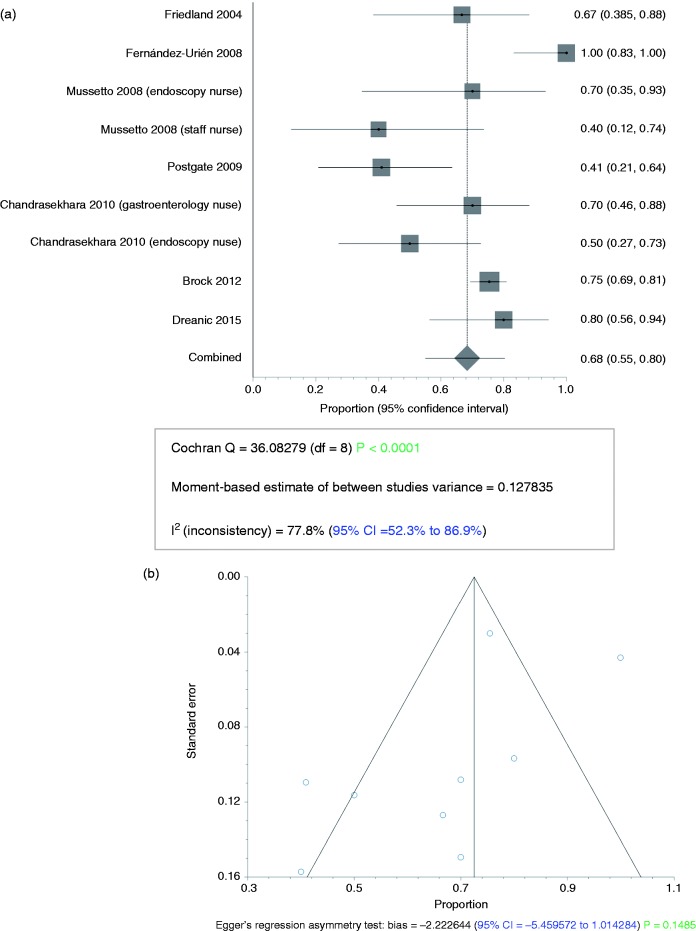

Studies reporting outcomes as number of CE videos where there was agreement between the nurse and RS

Seven of the 16 studies reported results as number of videos where there was agreement on overall findings/diagnosis between the nurse and RS.23,24,26,27,31,33,36 Meta-analysis results are summarised in Table 3. The overall proportion of videos with agreement was 0.68 (95% CI 0.55–0.80). The random effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (Q = 36.083, d.f.(Q) = 8, I2 = 77.8%, p < 0.0001) but there was no publication bias (p = 0.149) (Figure 3(a): forest plot; Figure 3(b): funnel plot).

Table 3.

Summary of meta-analysis results in studies reporting outcomes as number of CE videos where there was agreement between the nurse and RS.

| Subgroup | Studies (n) | CE videos where nurses' overall findings agreed with RS (n) | Total CE videos (n) | Pooled proportion of nurses' findings compared to RS findings (95% CI) | I2 (heterogeneity) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 7 | 256 | 357 | 0.683 (0.549–0.803) | 77.8% (52.3–86.9%) |

| Full studies only | 3 | 195 | 262 | 0.767 (0.454–0.970) | 92.0% (77.3–95.7%) |

| Nurses with GI endoscopy experience vs RS | 7 | 238 | 327 | 0.711 (0.556–0.844) | 80.8% (55.2–89.0%) |

Abbreviations: CE, capsule endoscopy; CI, confidence interval; n, number; RS, reference standard.

Figure 3.

(a) Forest plot showing pooled proportion of whole capsule endoscopy examinations/videos where agreement was achieved between nurses and reference standards. (b) Funnel plot depicting publication bias for studies reporting proportion of capsule endoscopy examinations/videos where agreement was achieved.

In studies involving only nurses who had prior GI endoscopy experience, the proportion of videos with agreement was 0.71 (95% CI 0.56–0.84).

When only studies published as full manuscripts were considered, the pooled proportion of videos with agreement between the nurses and physicians was 0.77 (95% CI 0.45–0.97). The random effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (Q = 24.988, d.f.(Q) = 2, I2 = 92%, p < 0.0001); a funnel plot could not be obtained due to the small number of studies in this group.

‘Over-reporting’ by nurses

Nine studies presented data relating to ‘over-reporting’ of CE findings.10,23,27,28,32,33,35 In these studies, 10 nurses reading 510 CEs had 324 ‘over-reported’ findings (i.e. false positives or findings later deemed insignificant by physicians). Eight nurses who ‘over-reported’ findings had GI endoscopy experience. Six of these had had some form of CE training prior to reading the videos for the studies. In general, the nurses took longer than physicians to read CEs; however it must be noted that all the physicians had previous CE reading experience. Missed pathology by the nurses, although reported very heterogeneously, was mainly mucosal ulcers and angioectasias, i.e. there were no sinister findings missed.

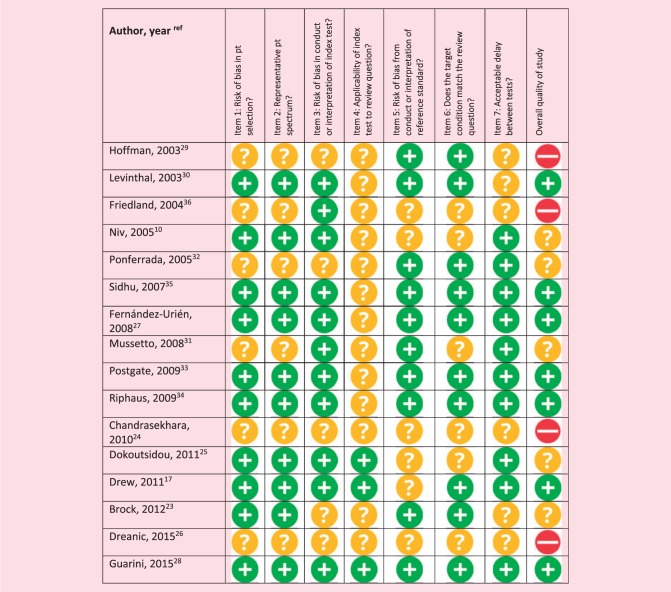

Quality assessment of included studies

Our study group was markedly heterogeneous on QUADAS-2 analysis (Table 4). In most studies the applicability of the index test, nurse interpretation of CE, was unclear due to the involvement of nurses with no or little prior CE training, which would likely not be the case if nurses were to be employed routinely to read CEs in clinical practice. There was a significant amount of missing information making quality assessment difficult as many of the studies were presented in abstract form.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS)-2 results for the included studies.

Discussion

The overall results of this meta-analysis imply that nurses perform at a similar level to physicians in CE reading. Our results corroborate those of previous studies showing nurse endoscopists as CE pre-readers can free up time and resources in stretched healthcare systems, leading to significant cost savings.1–3 However, based on our results, we advocate that these benefits could be further enhanced by allowing nurses or other physician extenders to act as independent CE readers, similar to the well-established role of nurse endoscopists in conventional diagnostic GI endoscopy.1,2,4–7 However, reimbursement for CE reading by non-physicians has yet to be recognised in several centres worldwide. The current role of nurses in capsule endoscopy is limited to pre-reading, following which physician review is still necessary for official reporting.

There remained some missed lesions when CEs were reported by nurses. However, in all but one of our studies, the nurses had not had extensive CE training whereas all the physicians had been trained in CE. This is further supported by the findings from Postgate et al.,33 an outlier study in this meta-analysis. The authors showed that an endoscopy nurse with no prior CE reading experience improved more drastically over 22 CE videos compared to trainee physicians.33 The nurses' performance in this meta-analysis is similar to that of other (potential) physician extenders such as non-CE-trained GI trainees/residents and medical students. Zheng et al. showed that CE pathology detection rates by physicians were low and little influenced by increasing CE experience.37 Rondonotti et al. also reported low detection rates and inter-observer agreement amongst physicians.38 In a study by Chen et al.,18 nine medical students with no prior GI endoscopy or CE experience had an average sensitivity of 67% which improved with the number of cases read. John et al. similarly found that gastroenterology trainees improved in agreement with an experienced CE trainer over time.19 Bossa et al. compared performance of an inexperienced nurse and physician trainee,11 finding generally good agreement for a range of lesions.

Furthermore, the missed lesions may not be highly clinically significant; in our group of studies, the majority of lesions missed by nurses but reported by physicians were specified to be minor or insignificant in nature. From the studies where a more detailed breakdown of lesions was available, the nurses did not report 9/146 angioectasias, 13/59 ulcers, 4/45 instances of general mucosal abnormality/erythema, 1/13 areas of lymphoid hyperplasia/lymphangiectasias and 1/1 possible submucosal lesion. There was however total agreement for blood in the lumen and small bowel tumours. Conversely, nurses tended to ‘over-report’ non-pathological findings or false positives. This could be due to the relative inexperience of the nurses in our meta-analysis. All but one had no CE reading experience prior to taking part in these studies. ‘Over-reporting’ and filtering of findings is a necessary part of the learning curve for all CE readers, whether nurses or physicians. Therefore we would argue that ‘over-reporting’ is preferable to overlooked pathology, and would improve with training, time and accumulated experience. The better performance of nurses with endoscopic experience compared to those without implies that prior exposure to endoscopy had improved their performance. Furthermore, the RS for comparison in this meta-analysis were highly variable, ranging from gastroenterologists with experience of 50 CEs to > 2000 CEs. The majority of physicians in these studies had experience of between 50 and 200 CEs.

There are a number of limitations in this meta-analysis. Firstly, there is a lack of reported formal CE accreditation by which to judge RS, which is particularly likely in the earlier studies. Therefore the RS used in the majority of these studies can only be weakly considered the ‘gold standard’ for detection of SB pathology as any missed lesions by the reporting physicians in these studies were not well documented. Recently, the ASGE has published guidelines for credentialing CE readers, although these are currently not in common use.12,13 Albert et al. have proposed a simple evaluation tool (ET-CET) for SBCE training,39 showing that diagnostic yield in CE trainees increased up to 25 CEs read, then plateaued. They also showed that diagnostic skills improved following formal CE courses with hands-on training, regardless of previous experience, profession or course setting. Other significant limitations are study design and heterogeneity given the number of abstracts included. Another limitation is the lack of reporting on agreement for normal CEs. Finally, although our data is based on nurses alone, we believe our results can be extended to non-nursing physician extenders such as clinical physiologists and allied healthcare professionals who already routinely perform similar clinical duties.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis supports a more active role for nurses in CE reading. The good agreement obtained between novice nurses and relatively experienced physicians suggests that nurses could function as independent CE readers, given adequate training and formal credentialing. Nurses with a background or prior experience in GI endoscopy, in particular, could be offered the option of training as independent CE readers. However, we acknowledge the fact that reimbursing nurses for this role may be an issue in certain healthcare systems. Overall, achieving diagnostic accuracy is a conscious process in every field in medicine and often involves seeking second opinions and specialisation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Andrew S Brock, Carol Burke and Rocio Lopez for providing further information about their studies.

Declaration of conflicting interests

DY: Grant from Dr Falk Pharma/Core; travel support from Dr Falk Pharma. AK: Honoraria from and member of advisory board for Dr Falk Pharma UK; material support for research from Synmed UK; travel support from Almirall and Dr Falk Pharma. MM: Research grant for materials from Synetics Medical and Jinshan Science and Technologies; travel support from Tillotts Pharma.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Verschuur EML, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Nurses working in GI and endoscopic practice: a review. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 65: 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drew K, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS, et al. The nurse endoscopist. Gastroenterol Nurs 2013; 36: 209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caunedo Alvarez A, Garcia-Montes JM, Herrerias JM. Capsule endoscopy reviewed by a nurse: is it here to stay?. Dig Liver Dis 2006; 38: 603–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton C, Kamm MA. Specialist nurses in gastroenterology. J R Soc Med 2002; 95: 331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Putten P, ter Borg F, Adang R, et al. Nurse endoscopists perform colonoscopies according to the international standard and with high patient satisfaction. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duthie GS, Drew PJ, Hughes MAP, et al. A UK training programme for nurse practitioner flexible sigmoidoscopy and a prospective evaluation of the practice of the first UK trained nurse flexible sigmoidoscopist. Gut 1998; 43: 711–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathmakanthan S, Murray I, Smith K, et al. Nurse endoscopists in United Kingdom health care: a survey of prevalence, skills and attitudes. J Adv Nurs 2001; 36: 705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotherstone H, Vance M, Edwards R, et al. Uptake of population-based flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer: a nurse-led feasibility study. J Med Screen 2007; 14: 76–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo SK, Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, et al. How should we do capsule reading?. Tech Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 8: 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niv Y, Niv G. Capsule endoscopy examination–preliminary review by a nurse. Dig Dis Sci 2005; 50: 2121–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bossa F, Cocomazzi G, Valvano MR, et al. Detection of abnormal lesions recorded by capsule endoscopy. A prospective study comparing endoscopist's and nurse's accuracy. Dig Liver Dis 2006; 38: 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faigel DO, Baron TH, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: guidelines for credentialing and granting privileges for capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61: 503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sidhu R, McAlindon ME, Davison C, et al. Training in capsule endoscopy: are we lagging behind?. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012, pp. 175248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al. Quadas-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Int Med 2011; 155: 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drew K, Sidhu R, Sanders D, et al. Blinded controlled trial comparing image recognition, diagnostic yield and management advice by doctor and nurse capsule endoscopists. Gut 2011; 60: A195. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen G, Chan S, Quan C, et al. Sensitivity and inter-observer variability for capsule endoscopy image analysis in a cohort of novice readers. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: P165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.John S, Kejariwal D, Jamieson CP. Inter-observer variations on interpretation of capsule endoscopy and its impact on training requirements for competence. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 67: AB301. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postgate AJ, Fitzpatrick A, Bassett P, et al. Polyp detection and size estimation at capsule endoscopy - Does experience improve accuracy? A prospective animal-model study. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 65: AB316. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiotani A, Honda K, Kawakami M, et al. Evaluation of RAPID 5 Access software for examination of capsule endoscopies and reading of the capsule by an endoscopy nurse. J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiotani A, Honda K, Kawakami M, et al. A trained non-physician is superior to endoscopists inexperienced in capsule endoscopy reading – capsule endoscopy reading by using QuickView mode. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: Sa1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brock A, Freeman J, Roberts J, et al. A resource efficient tool for training novices in wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs 2012; 53: 317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandrasekhara V, Dunbar KB, Dongen MV, et al. Determination of competency for Wireless Capsule Endoscopy in digestive healthcare practitioners. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71: AB371. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dokoutsidou H, Karagiannis S, Giannakoulopoulou E, et al. A study comparing an endoscopy nurse and an endoscopy physician in capsule endoscopy interpretation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 23: 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dréanic J, Dhooge M, Goncalves V, et al. The small bowel videocapsule endoscopy: may we delegate it to nurses?. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: S–826. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernández-Urién I, Espinet E, Pérez N, et al. Capsule endoscopy interpretation: the role of physician extenders. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100: 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guarini A, De Marinis F, Hassan C, et al. Accuracy of trained nurses in finding small bowel lesions at video capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs 2015; 38: 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffman BJ, Glenn T, Varadarajulu S, et al. Can we replace gastroenterologists with physician extenders for interpretation of wireless capsule endoscopy?. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: A245. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levinthal GN, Burke CA, Santisi JM. The accuracy of an endoscopy nurse in interpreting capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 2669–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mussetto A, Santoro D, Conigliaro R, et al. Capsule endoscopy examination: a preview by an endoscopic nurse and a staff nurse. Preliminary results. Dig Liver Dis 2008; 40: S153. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponferrada A, Anton S, Gonzalez-asanza C, et al. Interobserver agreement between experienced endoscopist and endoscopy nurse in the detection of lesions in the capsule endoscopy examination. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61: AB178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postgate A, Haycock A, Fitzpatrick A, et al. How should we train capsule endoscopy? A pilot study of performance changes during a structured capsule endoscopy training program. Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54: 1672–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riphaus A, Richter S, Vonderach M, et al. Capsule endoscopy interpretation by an endoscopy nurse: a comparative trial. Z Gastroenterol 2009; 47: 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidhu R, Sanders DS, Marshall L, et al. Capsule endoscopy: is there a role for nurses as physician extenders?. Gastroenterol Nurs 2007; 30: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedland S, Wu K, Soetikno RM. A pilot study of capsule endoscopy reading by a nurse endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: P179. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Hawkins L, Wolff J, et al. Detection of lesions during capsule endoscopy: physician performance is disappointing. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rondonotti E, Soncini M, Girelli CM, et al. Can we improve the detection rate and interobserver agreement in capsule endoscopy?. Dig Liver Dis 2012; 44: 1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albert JG, Humbla O, McAlindon ME, et al. A simple evaluation tool (ET-CET) indicates increase of diagnostic skills from small bowel capsule endoscopy training courses. Medicine 2015; 94: e1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]