Abstract

The relationship between ethnic socialization by parents and peers and ethnic identity development was examined over a seven-year time span in a sample of 116 internationally adopted Korean American adolescents. Parent report data was collected in 2007 (T1) when the adopted child was between 7–13 years old and again in 2014 at ages 13–20 years old (T2). Adolescent report data also was collected in 2014. We examined differences in parent and adolescent reports of parental ethnic socialization at T2, changes in parent reports of ethnic socialization from T1 to T2, and the relationship among ethnic socialization by parents at T1 and T2, ethnic socialization by peers at T2, and ethnic identity exploration and resolution at T2. Results indicated parents reported higher levels of parental ethnic socialization than did adolescents at T2. Parent-reports of parental ethnic socialization also decreased between childhood and adolescence. Adolescents reported higher parental ethnic socialization than peer ethnic socialization at T2. Path analysis demonstrated positive indirect pathways among parental ethnic socialization at T1, parental ethnic socialization and peer ethnic socialization at T2, and ethnic identity exploration and ethnic identity resolution at T2. The study highlights the cultural experiences of transracial, transnational adopted individuals, the role of both parents and peers in ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development, and the importance of longitudinal and multi-informant methodology.

Keywords: ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, international adoption, peer socialization, adolescents, longitudinal

Introduction

Ethnic socialization is often viewed as a parent-driven process that contributes to ethnic identity development, but there is growing evidence that ethnic socialization becomes more peer-driven during adolescence (Hu, Kim, Lee & Lee, 2012). This shift in socialization agents is consistent with the broader socialization literature (Harris, 1995). However, research on ethnic socialization efforts by parents and peers is limited. For international adoptive families, the ethnic socialization process is even more complicated due to the transracial, transnational nature of most of these relationships (Lee, 2003; Massati, Vonk, & Gregoire, 2004). In this study, we explored ethnic socialization experiences in transracial, transnational adoptive families. Specifically, we examined difference in parent and adolescent reports of parental ethnic socialization, changes in parental ethnic socialization practices over time, and the relationship among ethnic socialization by parents, ethnic socialization by peers, and ethnic identity exploration and resolution over a seven-year time span.

Transracial, Transnational Adoption

An estimated one million children have been adopted internationally worldwide since the 1940s (Selman, 2012). South Korea is the largest sending country accounting for more than 20% of all international adoptions. In the United States, over 125,000 South Korean children have been adopted by Americans, who are predominantly White (Raleigh, 2013). In fact, 84% of international adoptions can be considered transracial with parents and children from different racial backgrounds (Selman, 2012). Despite the transracial and transnational nature of internationally adopted youth, their ethnic experiences are not well understood (Lee, 2003).

Transracial and transnational adoption exposes adoptive parents and adopted children to distinctive familial challenges that differ from the developmental tasks of non-adoptive, same-race family life (Brodzinsky, 1987; Samuels, 2009). Notably, transracially, transnationally adopted children are often treated as members of the majority culture by family members (and sometimes themselves) but are treated as ethnic minorities in society (Lee, 2003). This conflicting set of experiences can result in adopted youth who demonstrate discomfort with their appearances and have difficulty coming to terms with what it means to be members of an ethnic minority group (Feigelman, 2000). The exploration and resolution of these unique ethnic-specific developmental tasks are especially important in developing a stable and positive self-identity (Brodzinsky, 1987; Kirk, 1964).

Ethnic Socialization

Learning about and making meaning out of one’s ethnic heritage is a dynamic process known as ethnic socialization. Ethnic socialization specifically refers to beliefs, messages and practices that instruct children and adolescents about their racial or ethnic heritage and promote pride and commitment in their ethnic identity development (Hughes & Chen, 1999; Hughes et al., 2006; Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen, 1990). Numerous studies have documented the link between ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development (Tran & Lee, 2010; Hughes, Bachman, & Fuligni, 2006; Hughes & Johnson, 2001; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). However, ethnic socialization practices do not remain static over time and shift with the developmental needs of the child (Lee, Grotevant, Hellerstedt, & Gunnar, 2006). Parents may also conceptualize ethnic socialization differently from their children and vary in their willingness to engage in such socialization practices (Hughes et al., 2008). Moreover, both parents and peers are primary ethnic socialization agents (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). These changes and differences in ethnic socialization are less studied in both adopted and non-adopted populations, but may be even more noticeable in transracial, transnational adoptive families given the different sets of ethnic and racial experiences of parents and children.

Ethnic socialization for transracial, transnational adoptive families with Korean American children may include ethnic-specific practices, such as discussing important Korean events, celebrating Korean holidays, and reading books about Koreans and Korean Americans. Adoptive families also need to navigate the added layer of being a family with a child who is an ethnic minority in society. Parents, for instance, may discuss the meaning, importance, and challenges of being both adopted and Korean American. However, the ethnic socialization process of adoptive families may be complicated by racial and ethnic differences among parents and children (Barn, 2013; Lee, et al., 2006; Rojewski, 2005; Scroggs & Heitfield, 2011). Hu, Anderson, and Lee (2015), for instance, found in a study1 of families with adolescents adopted internationally from South Korea that parents and adolescents often have different perceptions of ethnic socialization, with parents reporting more parental ethnic socialization practices compared to adolescents. Other research indicates that adoptive parents are more inclined to emphasize episodic, explicit forms of socialization, whereas adolescents seek same-ethnic friendships and more everyday conversations about ethnicity (Kim, Reichwald, & Lee, 2012; Song & Lee, 2009). The parent-child discrepancy in self-reports may occur due to conceptual difference in ethnic socialization or adoptive parents’ tendency to over-estimate their engagement of ethnic socialization practices with their children (Kim et al., 2012). The complexity of transracial and transnational experiences, coupled with the potentially differing views on ethnic socialization, precipitate the need to include both parent and adolescent perspectives in studying ethnic socialization.

How parents ethnically socialize a child during early childhood likely differs from how parents ethnically socialize their child during middle childhood and adolescence. This question is particularly relevant as children enter adolescence and begin to make meaning out of their own and others’ ethnic identities (Ruble et al., 2004; Brown, Alabi, Huynh, & Masten, 2011). As children gain a deeper understanding of their ethnic identities, parents may engage in less ethnic socialization to allow for other socialization practices, such as discussing prejudice and discrimination. In a cross-sectional study of children 4–14 years old, Hughes and Chen (1997) found a small correlation (r = .16) between child age and ethnic socialization. Lee and colleagues (2006), by contrast, found greater parental efforts at ethnic socialization with internationally adopted children (ages 5–9) than internationally adopted adolescents (ages 10–18). To date though, there are few, if any, published longitudinal studies examining changes in ethnic socialization across developmental periods.

Although most attention is placed on the role of parents in ethnic socialization, peers serve as equally important socialization agents (Hu et al., 2012; Syed, 2012; Rivas-Drake, Umaña-Taylor, Schaefer, & Medina, 2017; Yip, Douglass, & Shelton, 2013). Ethnic socialization among peers is more likely to occur during adolescence when adolescents seek more autonomy from parents and are more influenced by peer relationships (Harris, 1995). In studies of non-adopted ethnic minority youth, ethnic socialization often takes place with peers who share similar levels of ethnic identity (Schwartz et al., 2014). These intraracial friendships, in turn, likely guide the way in which ethnic minority adolescents experience and engage in ethnic socialization. For example, Latin American, Asian, and White adolescents’ increase in intraracial friendships was associated with increases in ethnic identity development (Kiang, Witkow, Baldelomar, & Fuligni, 2010). For ethnically diverse youth, having more diverse friendships was related with higher ethnic-racial identity exploration at a later time (Rivas-Drake et al., 2017). For Asian adolescents, contact with same-ethnic friends was associated with higher ethnic identity (Yip et al., 2013). In a study with college-aged friends, “ethnic identity homophily2” was similarly related to individuals’ tendency to engage in conversations with their friends about ethnicity-related issues (Syed & Juan, 2012). Thus, it may be that engaging with ethnically diverse and similar friends about ethnicity-related issues helps to clarify and stimulate thinking regarding ethnic identity. Moreover, talking about ethnicity-related issues with intraethnic friends may keep that identity active in one’s mind. In transracial, transnational adoptive families, parents were the most frequent ethnic socialization agents for transracially adopted adolescents, but conversations with peers in general, regardless of ethnic or racial similarity, regarding ethnicity had a greater association with transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents’ ethnic identity development (Hu et al., 2012). These findings suggest peers – whether intraethnic, intraracial or not – are a crucial aspect of ethnic socialization and may serve different roles depending on the age of the target individual.

Channeling Hypothesis

The channeling hypothesis (Himmelfrab, 1979) captures the process between parent and peer cultural socialization in development. Channeling has been primarily studied with religious socialization – parents shape children’s religious environment by “channeling” or placing them into religious communities and activities (Himmelfrab, 1979). The process allows children to socialize with their religious peers and develop their religious identity over time. Once children enter adolescence and expand their social network outside the home, these rooted socialization agents continue to indirectly shape their religious identity (Cornwall, 1989; Park & Ecklund, 2007). Channeling captures the transactional nature among parents, adolescents, and peers, as well as the longitudinal influence of parent’s socialization efforts on youth’s future socialization patterns and outcomes.

Channeling hypothesis has been studied to a lesser extent outside of religious socialization research. A longitudinal study following African American families found that parents who were authoritative in their parenting style were able to deter adolescents’ affiliation with deviant peers and involvement in delinquent behavior (Laird, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2008). Another longitudinal study found that parental monitoring reduced the selection of delinquent peers for youths three years later (Tilton-Weaver, Burk, Kerr, & Stattin, 2013). In the same study, when parents expressed high levels of disapproval of delinquent peers, it reduced the rates of adolescents engaging in delinquency. Although limited, these studies suggest channeling similarly may occur for other forms of socialization as children transition into adolescence.

Channeling hypothesis offers a helpful framework to understand the ethnic socialization process during adolescence. Parents may indirectly promote adolescents’ peer ethnic socialization practices by engaging them in ethnically diverse environments, such as enrolling them in an ethnically diverse school (e.g., Feigelman & Silverman, 1984) or modeling behavior that promotes racially and ethnically similar peer friendships. In doing so, children are likely to experience peer ethnic socialization and, in turn, to develop their ethnic identities. For example, immigrant parents send their children to language schools to learn ethnic language, as well as attend relevant cultural events (Park & Sarker, 2007; Zhou & Kim, 2006). Channeling for transracial, transnational adoptees may occur when adoptive parents move to a neighborhood populated with more ethnic minorities, enroll adoptees in culture camps, or arrange play dates with children who share similar ethnic backgrounds. It also may occur through encouraging friendships with peers who are more open to conversations about ethnic and racial differences. Through these parent-initiated activities, transracial, transnational adoptees will have opportunities to interact with peers who are more open to discussions about ethnicity and race, and perhaps increase their propensity to engage in ethnic socialization practices in the future.

Ethnic Identity Development

Ethnic identity broadly refers to the degree to which an individual identifies as being a member of an ethnic group, and is a crucial aspect in the development of self-concept and psychological functioning for ethnic minorities (Phinney, 1990; Rumbaut, 1994). Ethnic identity development is theorized as a dynamic product that is achieved over time and through various social contexts (Caltabiano, 1984; Hogg, Abrams, & Patel, 1987; Syed & Azmitia, 2009). In particular, ethnic identity development gains more prominence as youth develop the cognitive abilities to process the information they receive regarding prejudice and discrimination (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014; Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). As individuals become more aware of their status as an ethnic minority and become more independent in the decision-making process, the process of exploring and committing to their ethnic identity becomes a more prominent developmental task.

When discussing the process of ethnic identity development, a distinction should be made between exploration and commitment because they follow distinct developmental courses (Pahl & Way, 2005) and are related to different psychological outcomes (Lee & Yoo, 2004). Ethnic identity exploration is a period in which adolescents search and examine the meaning and history of their ethnic group memberships, as well as participate in cultural activities to affirm their ethnic group membership. Ethnic identity commitment refers primarily to the resolution and clarity with the subjective significance of ethnic group membership to one’s overall identity (Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004).

Other ethnic identity scholars have included positive affect toward one’s ethnic group as a part of ethnic identity commitment (Phinney, 1992). However, private regard more accurately reflects the content of ethnic identity and is not consistent with Erikson’s (1968) theoretical work on identity development (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Thus, it is possible that an individual has resolution and clarity about the significance of being a member of an ethnic group but not necessarily concurrent positive private regard. Therefore, in this study, we focused on ethnic identity development, as operationalized and measured by exploration and resolution, and not the content of ethnic identity (i.e., private regard) (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014).

For transracially, transnationally adopted individuals, a more committed ethnic identity has been found to be associated with better psychological adjustment (Cederblad, Höök, Irhammar, & Mercke, 1999; Feigelman & Silverman, 1984; Yoon, 2001). By contrast, a more recent study found ethnic identity exploration was correlated with worse psychological adjustment, whereas other aspects of ethnic identity, such as resolution and private regard, were unrelated to adjustment (Lee, Lee, Hu, & Kim, 2015). Ethnic identity, measured by combining exploration and commitment, also has been found to mediate the relationship between parental ethnic socialization and psychological well-being among transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents (Basow, Lilley, Bookwala, & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2008; Yoon, 2001). These extant studies suggest the relationship between ethnic identity development and adjustment is complex among adopted Korean Americans and understanding the distinct developmental pathways toward ethnic identity exploration and resolution is needed.

Present Study

This study advances current research on ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development in a number of ways. Although socialization becomes more peer-driven during adolescence (Harris, 1995), most studies on ethnic socialization still focus only on parental ethnic socialization, draw from parent reports, and use single-informant methodology. Thus, the transactional nature among parent, children, and peers are not captured in these studies. Further, single-informant studies do not account for potential discrepancies between parents and children in perceptions on parental ethnic socialization (Hu et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012). Changes in ethnic socialization, particularly during childhood to adolescence, also have not been explored in these cross-sectional studies. Additionally, the ethnic experiences of transracially, transnationally adopted youth are not well understood (Lee, 2003). For these youth, the ethnic socialization process is complicated by the transracial, transnational nature of their family and peer relationships, but most adoption studies largely overlook the possible role of ethnic socialization and its correlates in psychological development and adjustment.

In this study, we incorporate parent reports of parental ethnic socialization, adolescent report of parental and peer ethnic socialization, and adolescent report of ethnic identity exploration and commitment. The longitudinal and multi-informant nature of the study also allows an examination of the potential long-term associations of parental ethnic socialization with ethnic identity development in transracial, transnational adoptive families. The present study addressed the following hypotheses:

H1. Transracial, transnational adoptive parents would report higher levels of ethnic socialization than transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents.

H2. Parental ethnic socialization would decrease from 2007 (Time 1; T1), when transracially, transnationally adopted youth were younger to 2014 (Time 2; T2), when the same group of transracially, transnationally youth were older,

H3. We expected the level of ethnic socialization to be greater with peers as socialization agents than with parents.

H4. There will be positive indirect paths among T1 parental ethnic socialization, T2 parental ethnic socialization and T2 peer ethnic socialization, and T2 ethnic identity exploration and resolution.

Method

Participants

The sample included internationally adopted Korean American individuals and one of their adoptive parents. The study followed up with families who participated in the Korean Adoption Survey (KAD) Project in 2007 during which the adopted youth was between the ages of 7–13. The adoptees and families were recruited in 2007 from a registry of international, transracial adoptees whose families reside mainly in Minnesota, United States.

In 2007 (T1), a total of 593 out of 786 families (with some families having more than one child) expressed interest in participating in the study. A survey was completed for each adopted child by one parent who self-identified as the primary caretaker, making a total of 578 returned parent surveys for a return rate of 73.5% (Lee, Lee, Hu, & Kim, 2015). Out of 578 surveys for adopted youth between age 7 and 18, 225 were completed for adopted children who were between the ages of 7 and 12. Youth between the ages of 7 and 12 did not participate in T1 data collection due to age (age 13 was the cutoff). Out of 225 surveys, 14 were excluded due to discrepancies in reported gender (i.e., parents reported incorrect gender for the child) or being duplicates (i.e., the same parent reported on the same child multiple times). Thus, the final sample size of parent-child dyads at T1 was 211. In 2014 (T2), adoptive parents from T1 (n = 211) were contacted, and 151 parent-adolescent dyads agreed to participate in the study. Of the 60 adolescents who were excluded, six had outdated contact information, and 40 did not respond to repeated outreach. Out of the 151 dyads, 119 dyads of parent and adoptee surveys were completed. Three parent-adolescent dyads were further excluded from further analysis due to discrepancies of parent gender from T1 and T2 datasets; thus, 116 dyads were included in final analysis, making a final retention rate of 55%.

Of the 116 adopted Korean American adolescents included in the final sample, 56 adolescents (48.3%) identified as female, 58 adolescents (50.0%) identified as male, and one adolescent (0.9%) did not disclose gender. The mean age of the sample was 9.37 years (SD = 1.69) in T1 and 16.33 years (SD = 1.71) in T2. All of the adolescents were internationally adopted from South Korea at the mean age of 7.86 months (SD = 5.17), with 105 adolescents (90.5%) adopted before 12-months-old.

Of the 116 adoptive parents included in the final sample, 107 parents (92.2%) identified as female, seven parents (6.0%) identified as male, and two parents (1.7%) did not disclose gender. The mean age of the parents was 53.41 years (SD = 4.37). The majority of the parents (n=114, 98.3%) identified as White, two parents identified as Korean American (with their spouses being White). Further analysis indicated the results obtained using the 116 sample were identical to the ones obtained using the 114 sample with the primary reporters being White; therefore, the results using the 116 sample were reported. In terms of education level and income, 81.9% adoptive parents reported having obtained a Bachelor’s or higher degree, and 50.5% reported an income of $126,000 or more. One hundred and thirteen parents (97.4%) reported having a spouse and three parents (2.6%) reported not having a spouse in T2. Average age of the spouse was 54.23 years (SD = 4.32). One hundred and eight parents (93.1%) identified their spouse as White and three parents (2.6%) identified their spouse as Asian American. Of the 103 parents who reported their spouses’ education level, 85 parents (75.2%) reported their spouses having obtained a Bachelor’s or higher degree. The demographics of the adoptive family in the current sample (i.e., predominantly White, highly educated and of high income) are representative of those in the U.S. population that adopt internationally (McGue et al., 2007).

We compared the 116 parents who completed both T1 and T2 data collections (respondents) with the 109 T1 only (non-respondents) parents on the key study variables for attrition analysis. There were no significant differences on parent’s age, gender, ethnicity, parent’s education level, or income. However, the respondent group reported higher level of ethnic socialization in T1 relative to the non-respondent parents, F(1, 223) = 5.12, p = .025, η2= .02 (Respondent parents: M = 2.85, SD = .67, n = 116; non-respondent parents: M = 2.63, SD = 0.74, n = 109).

Procedure

In 2014 (T2), updated contact information of the adoptive families was retrieved from the International Adoption Project registry. Adoptive parents who consented to participate in the KAD project in 2007 (T1) (refer to procedure in Lee, Lee, Hu, & Kim, 2015) were contacted via email, letters, or phone to see if they would be interested in participating in this longitudinal study. Each family was contacted at most three times. After the target adoptive parent provided consent, they were asked to provide assent for their children who were under the age of 18. All participants provided electronic consent or assent prior to study participation. Parents and their adolescents completed parent- and adolescent-versions of the online survey respectively. Each parent who completed the survey received an Amazon gift card of $10.00 and each adolescent received an Amazon gift card of $20.00 due to the longer length of the adoptee survey. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Measures

The study included a variety of measures from both T1 and T2.

Demographic variables

Parent completed a demographic questionnaire in T1, and parent and adolescent each completed a demographic questionnaire in T2 to obtain biographical data including their age, gender, family income, relationship status, education, etc.

Parental ethnic socialization

Parental ethnic socialization was assessed using the ethnic socialization subscale from the Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Socialization measure (Johnston et al., 2007, adapted from Hughes & Chen, 1997). The ethnic socialization subscale pertains to the extrinsic ways in which parents teach adopted children or adolescents about Korean culture and history (e.g., “… talked to child about important Korean people or historical events.”). This measure was reported by parents only in T1 and was reported by both parent and adolescent in T2. Each item was modified to reflect the ethnic socialization experiences relevant to Korean adoptive homes (i.e., Black was replaced with Korean and/or Asian). T2 survey for adolescents was further modified to reflect the ethnic socialization experiences relevant for adolescents. For example, “… play with other children who are Korean or Asian Americans” was changed to “… socialize with other adolescents who are Korean or Asian Americans.” Two items were dropped because one (“I have encouraged my child to read books about other racial/ethnic groups”) was not directly related to Korean culture and the other (“I have talked with my child about dating Korean or Asian people”) was not relevant to T1 socialization practices for children of younger age. The final ethnic socialization subscale includes six items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very Often).

Although the scale was not originally developed specifically for adoptees, Johnston and colleagues (2007) demonstrated good internal consistency of parental ethnic socialization subscale, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from α = .81–.82 for transracially adopted Chinese and Korean American children between the ages of 4 to 20. In the current sample, Cronbach’s α = .79 for T1 parents, α = .84 for T2 parents, and α = .82 for T2 adolescents.

Peer ethnic socialization

Peer ethnic socialization was also assessed using the adapted version of the Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Socialization measure (Johnston et al., 2007, adapted from Hughes & Chen, 1997). Only adolescents completed this measure in T2. The measure was adapted to reflect the ethnic socialization experiences related to peer interactions. Adolescents were asked to indicate “how frequently you have done or said the following things with/to your close friends over the past year”, adapted from “how frequently your parents (one or both) have done or said the following things to you.” The instruction for peer ethnic socialization was not the exact equivalent to the parent ethnic socialization, as it reflected the interactive, horizontal nature of peer socialization that differs from the vertical transmission of culture from parents to children (Cavalli-Sforza, Feldman, Chen & Dornbusch, 1982). Similar to the parental ethnic socialization measure, all 6 items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very Often). Cronbach’s α = .83 for T2 adolescents.

Ethnic identity exploration and resolution

Adolescents completed the Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) in T2. The EIS is a 17-item self-report measure that is comprised of three subscales: exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Items are measured with a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 (Does not describe me at all) to 4 (Describes me very well). The distinct subscales allow researchers to examine the associations between each aspect of ethnic identity separately. The study included the developmental process aspects (i.e., exploration and resolution) rather than content aspect (i.e., affirmation) for the longitudinal analyses in examining ethnic identity development. The exploration subscale includes seven items that focus on the activities through which adolescents have explored their ethnic identity (e.g., “I have participated in activities that have exposed me to my Korean heritage”). The resolution subscale includes four items on clarity and meaningfulness of their ethnicity (e.g., “I understand how I feel about being Korean”). Umaña-Taylor and colleagues (2004) demonstrated that the three subscales obtained strong internal consistency. In the current study, Cronbach’s α = .90 (exploration), and α = .89 (resolution) for T2 adolescents.

Data Analysis Plan

Research questions were tested using Mplus 7.3 by creating a series of path models fitted with full information maximum likelihood method (FIML; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), which is the recommended approach to handle missing data. Missing data for the studied variables ranged from 1% to 3%, with most variables missing < 1%.

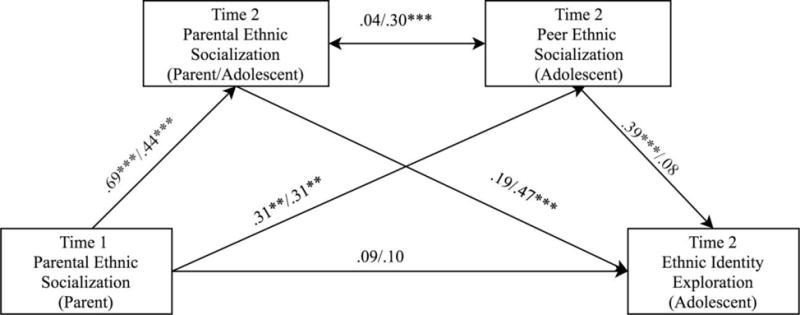

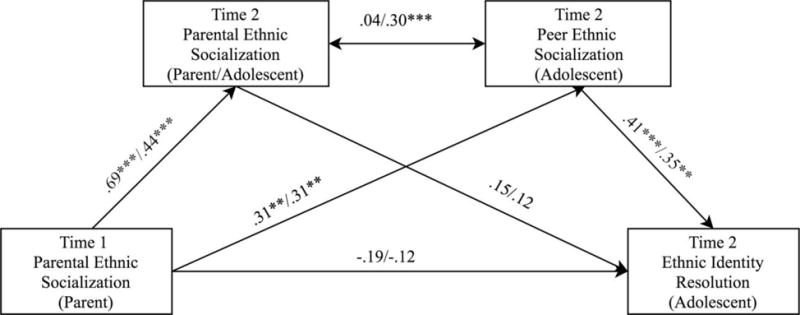

Two sets of path models were fitted for each outcome variable. For all tested models, the paths between parental and peer ethnic socialization T2 were bidirectional due to the exploratory nature of the channeling hypothesis and adjustment for temporal measurement covariance (i.e., both measures taken at T2). For ethnic identity exploration models (Model 1 & 2; see Figure 1), the relationship between parent ethnic socialization in T1 and ethnic identity exploration was tested for indirect pathways by (1) parent ethnic socialization in T2 reported by parent (Model 1) or reported by adolescent (Model 2), and (2) peer ethnic socialization in T2 reported by adolescent. Similar paths were conducted for ethnic identity resolution models (Model 3 & 4; see Figure 2); the relationship between parent ethnic socialization in T1 and ethnic identity resolution was tested for indirect pathways by (1) parent ethnic socialization in T2 reported by parent (Model 3) or reported by adolescent (Model 4), and (2) peer ethnic socialization in T2 reported by adolescent.

Figure 1.

Path Analyses for Ethnic Identity EXPLORATION – Model 1 and Model 2: Unstandardized regression coefficients for the relationships among T1 parental ethnic socialization, T2 parental ethnic socialization reported by parent (Model 1) or by adolescent (Model 2), T2 peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent, and T2 adolescent ethnic identity exploration, after controlling for child age and primary parent’s education. **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 2.

Path Analyses for Ethnic Identity RESOLUTION – Model 3 and Model 4: Unstandardized regression coefficients for the relationships among T1 parental ethnic socialization, T2 parental ethnic socialization reported by parent (Model 3) or by adolescent (Model 4), T2 peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent, and T2 adolescent ethnic identity resolution, after controlling for child age and primary parent’s education. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Two demographics variables, child age and primary parent’s education, were used as covariates for all variables in path analyses. Child age was included due to previous research findings that suggested parents socialized adopted children of 5–9 and those of 10–18-years-old differently (Lee et al., 2006). Further analyses indicated ethnic socialization was neither significantly correlated with age, nor differed when age was dichotomized into younger-than-9 and older-than-12 groups. We also correlated socialization and identity variables with child gender, age at adoption, parents’ income and education. Only primary parent’s education was significantly correlated with parental ethnic socialization in T1 (r = .23, p < .05) and parent ethnic socialization reported by adolescent in T2 (r = .24, p < .05) (See Table 1). Parent education was coded in 7 categories from 1 (less than high school to degree) to 7 (professional degree and/or doctorate degree), and it was treated as continuous variable in current analysis.

The hypothesized models were “just-identified” in the current study because each exogenous variable was hypothesized to directly influence each endogenous variable. Therefore, no model fit indices (i.e., chi-square of goodness-of-fit index, CFI, RMSEA, SRMR) will be reported. Both direct and indirect paths were evaluated. Three specific indirect paths were estimated in each of the four models: 1) indirect effect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to T2 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity, 2) indirect effect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to T2 peer ethnic socialization to ethnic identity, and 3) indirect affect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to T2 parental ethnic socialization to T2 peer ethnic socialization to ethnic identity. These effects were estimated by creating 1,000 bootstrap samples via random sampling with replacement. Simulation studies (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) have found that bias-corrected bootstrapping is the best statistical procedure for obtaining high statistical power and low Type I error rates.

In addition, for each of the four models, an alternative model was fitted where the relationship between parental ethnic socialization in T1 and peer ethnic socialization in T2 was tested for indirect pathways by (1) ethnic identity in T2 and (2) parent ethnic socialization in T2. Other model specifications to these alternative models were the same to those of the original models. Because both the original and the alternative models were “just-identified”, no model fit indices will be used for model comparison (as the fit indices are the same). The primary interest in fitting these alternative models was to examine the role of ethnic identity as a potential channel for youth seek out more parental and peer ethnic socialization. Thus, three alternative indirect paths were estimated: 1) indirect effect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity to T2 peer ethnic socialization, 2) indirect effect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity to T2 parental ethnic socialization to T2 peer ethnic socialization, and 3) indirect effect from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity to T2 peer ethnic socialization to T2 parental ethnic socialization.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and Pearson-product moment correlations for T1 and T2 measures are presented in Table 1. Bivariate correlations (Table 1) indicated that all ethnic socialization measures varied by reporters, socialization agents, and time of reporting were interrelated with each other. Ethnic identity exploration was significantly correlated with all ethnic socialization measures. Ethnic identity resolution was only significantly correlated with T2 parental ethnic socialization reported by adolescent and T2 peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent.

Study Hypotheses

Difference in reported parental ethnic socialization

A series of paired samples t-tests were conducted. Consistent with hypothesis 1, parent reported higher level of parental ethnic socialization in T2 compared with parental ethnic socialization reported by adolescent in T2 (t = 5.72, p < .001, d = .54).

Parental ethnic socialization decreased over time

Consistent with hypothesis 2, parental ethnic socialization as reported by parent in T1 and as reported by parent and adolescent in T2 decreased from T1 to T2 (t = 4.63, p < .001, d = .43; t = 9.63, p < .001, d = .91).

Parental and peer ethnic socialization

We also compared the ethnic socialization in T2 by different socialization agents. Contrary to hypothesis 3, peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent in T2 was lower than parental ethnic socialization in T2 reported by either parent (t = 11.83, p < .001, d = 1.11) or adolescent (t = 8.41, p < .001, d = .80).

Ethnic socialization on ethnic identity exploration

In Model 1, ethnic identity exploration was predicted by T1 parental ethnic socialization, and there was evidence that suggests potential indirect pathways by T2 parental ethnic socialization reported by parent and T2 peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent (Figure 1). As indicated in Table 2 (Model 1), T1 parental ethnic socialization was significantly correlated with T2 parental ethnic socialization (β = .69; SE = .07, p < .001) and T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .31; SE = .11, p < .01), but not with T2 ethnic identity exploration. T2 parental ethnic socialization was neither correlated with T2 peer ethnic socialization nor T2 ethnic identity exploration. T2 peer ethnic socialization was correlated with T2 ethnic identity exploration (β = .39; SE = .08, p < .001). Estimates of indirect effects suggested there was potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity exploration via T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .13; SE = .05, p < .01). In the alternative model, there was potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to T2 peer ethnic socialization via ethnic identity exploration (β = .14; SE = .05, p < .01).

In Model 2, the relationship between T1 parental ethnic socialization and T2 ethnic identity exploration demonstrated potential indirect pathways by T2 parental ethnic socialization reported by adolescent and T2 peer ethnic socialization reported by adolescent (Figure 1). T1 parental ethnic socialization was significantly correlated with T2 parental ethnic socialization (β = .44; SE = .11, p < .001) and T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .31; SE = .11, p < .01), but not with T2 ethnic identity exploration. T2 parental ethnic socialization was correlated with both T2 ethnic identity exploration (β = .47; SE = .08, p < .001) and T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .30; SE = .06, p < .001). T2 peer ethnic socialization was not significantly correlated with T2 ethnic identity exploration. Estimates of indirect effects suggested there was potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity exploration via T2 parental ethnic socialization (β = .21; SE = .07, p < .01). In the alternative model, there was also potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to T2 peer ethnic socialization via ethnic identity exploration (β = .13; SE = .05, p < .01).

Ethnic socialization on ethnic identity resolution

Results for Model 3 and Model 4 with T2 adolescent ethnic identity resolution are reported in Figure 2 and Table 2. Model 3 yielded similar results to Model 1. T1 parental ethnic socialization was correlated with T2 parent ethnic socialization (β = .69; SE = .07, p < .001) and T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .31; SE = .11, p < .01), but not with T2 ethnic identity resolution. T2 parental ethnic socialization was not correlated with T2 peer ethnic socialization or T2 ethnic identity resolution. T2 peer ethnic socialization was correlated with T2 ethnic identity resolution (β = .41; SE = .09, p < .001). Additionally, estimates of indirect effects suggested there was potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity resolution via T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .13; SE = .05, p < .01). In the alternative model, none of the indirect paths were estimated to be significant.

In Model 4, T1 parental ethnic socialization was significantly correlated with T2 parental ethnic socialization (β = .44; SE = .11, p < .001) and T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .31; SE = .11, p < .01), but not with T2 ethnic identity resolution. T2 parental ethnic socialization was correlated with T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .30; SE = .06, p < .001), but not with T2 ethnic identity resolution. T2 peer ethnic socialization was significantly correlated with T2 ethnic identity exploration (β = .35; SE = .11, p < .01). Additionally, estimates of indirect effects suggested there was potential indirect path from T1 parental ethnic socialization to ethnic identity resolution via T2 peer ethnic socialization (β = .10; SE = .05, p < .01). In the alternative model, none of the indirect paths were estimated to be significant.

Discussion

The study expands research on ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development by conducting a seven-year follow-up of ethnic socialization practices in transracial, transnational adoptive families. We specifically examined differences in parent and adolescent reports of parental ethnic socialization, changes in parental ethnic socialization over time, and the relationship among ethnic socialization by parents over a seven-year period, peer ethnic socialization, and ethnic identity exploration and resolution in transracial, transnational adoptive families.

We first examined whether adoptive parents and adolescent-aged adopted children agreed on the level of parental ethnic socialization. Results indicated adoptive parents reported higher levels of parental ethnic socialization than adolescents. This discrepancy in parent and adolescent report is consistent with research on discrepancies in ratings of parent-child relationships (Hu et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012; McElhaney, Porter, Thompson, & Allen, 2008; Stuart & Jose, 2012). Specifically, mothers tend to report engaging in more ethnic socialization efforts than adolescent reports of their mothers (Kim et al., 2012). It is possible that adoptive parents incorrectly rate their ethnic socialization practices as higher than what is actually being conducted. Alternatively, adopted youth and their parents may conceptualize the type, amount, and quality of ethnic socialization differently. This finding highlights the importance of employing multi-informant methodology in adoptive family research. Additionally, it demonstrates the complexity of ethnic socialization in transracial, transnational adoptive families (McGinnis, Livingston, Ryan, & Howard, 2009; Docan-Morgan, 2010).

One distinctive aspect of the study is that it is one of the longest longitudinal follow-up studies on ethnic socialization, as well as on transracial, transnational adoptive families. To this end, we were able to track changes in the frequency of parental ethnic socialization over a seven-year time span. Results indicated parental ethnic socialization decreased as transracially, transnationally adopted youth entered adolescence. This is consistent with extent cross-sectional research of ethnic socialization in that parents are likely to engage in less ethnic socialization as their children age (e.g., Hughes & Chen, 1997; Lee et al., 2006). As youth develop cognitive ability to process and understand complex cultural interactions, adoptive parents may be consciously decreasing ethnic socialization and increasing racial socialization practices, such as discussing prejudice and discrimination with their transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents. Future research should explore the process of parental and peer racial socialization for adopted adolescents.

Another contribution of the study is the incorporation of adolescents’ report of peer ethnic socialization. Contrary to study hypothesis, both transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents and adoptive parents reported higher parental ethnic socialization than peer ethnic socialization. This finding goes somewhat against the prevailing view that peers play a more prominent role than parents in adolescence (Harris, 1995). However, it is consistent with the Hu and colleagues (2012) study that found adoptive parents are still considered the primary socialization for this adoptive cohort. It may be that what is most important is the quality, not the frequency or quantity, of socialization that may contribute to ethnic identity development.

Furthermore, the longitudinal and multi-informant study design allowed a test of the channeling hypothesis. Regarding ethnic identity exploration, there was partial evidence to support possible channeling from parent ethnic socialization to peer ethnic socialization. Specifically, the study identified indirect pathways from parental ethnic socialization in childhood to parent and peer ethnic socialization in adolescence, and then to ethnic identity exploration in adolescence. In the alternative models, there was evidence to support indirect pathways from parental ethnic socialization in childhood to ethnic identity exploration, and then to peer ethnic socialization. Based on the findings from these competing models, it can be concluded that parental ethnic socialization is associated with peer ethnic socialization and ethnic identity exploration; however, directionality of the channeling hypothesis could not be determined. On the one hand, conversations about one’s ethnicity with parents and peers may encourage adolescents to further explore the meaning of this specific membership. On the other hand, it may be that ethnic identity exploration encourages further interaction among adolescents, parents, and peers, which is why both hypothesized and alternative models were valid. Of course, both explanations may be equally true given the dynamic and active nature of ethnic identity exploration.

Stronger support for the channeling hypothesis was found with ethnic identity resolution. Results suggest an indirect relationship between ethnic socialization in childhood and ethnic identity resolution in adolescence through both parental and peer ethnic socialization. The alternate models, by contrast, did not find any significant indirect paths. Unlike ethnic identity exploration, which is inherently dynamic and active, ethnic identity resolution reflects a more committed and clear understanding of one’s ethnicity that develops over time. That is, ethnic identity resolution is more likely to be influenced by childhood ethnic socialization from parents, nurtured through peer socialization, and then further developed in adolescence. In sum, these associations demonstrate the influence of early childhood parental ethnic socialization on adopted adolescents’ peer ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development.

The relationships between parental ethnic socialization, peer socialization, and adolescent ethnic identity have a few important implications. First, the findings provide partial evidence for the channeling hypothesis – adoptive parents’ introduction of culturally-relevant practices in childhood shaped adopted adolescent’s engagement with peers seven years later, and further solidify adopted adolescent’s search and comfort in their ethnic identity. Second, the indirect relationships suggest the importance of consistent parental ethnic socialization, as well as the addition of peer socialization in adolescence as transracially, transnationally adopted youth encounters more culturally-relevant experiences and undergo ethnic identity development. Third, the findings add to the limited peer ethnic socialization literature by demonstrating the importance of peers on ethnic identity development. Future studies should examine the content and context in which these ethnic-specific conversations and activities occur. It would be important to examine the effect of diversity, or lack thereof, within the peer group, given that many transracial, transnational adoptive individuals reside in ethnically homogenous neighborhoods.

Limitation

Although the study offers several interesting contributions, the findings must be considered alongside limitations. Given the complexity of analyses, a larger sample size to increase power would strengthen the study. Additionally, while adopted Korean American adolescents are the most populous group of international adoptees in the United States (Selman, 2012), the study only included adolescents who were adopted from South Korea during infancy. Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to internationally adopted children from other countries who are adopted at different ages and for whom resources to aid in cultural socialization vary greatly (Vonk, Lee, & Crolley-Simic, 2010).

Additional time points are needed to strengthen the study of channeling hypothesis. The present longitudinal study contains only two time points. Additionally, both parent and adolescent report of parent and peer ethnic socialization were measured concurrently in T2. Due to timing of parent and adolescent report, directionality of the channeling hypothesis could not be determined. While it provides fruitful information about the relationship between parent socialization and adolescent ethnic identity development, the study could not test for full mediation. It is critical for future research to include three or more time points from both parent and adolescent to fully test the channeling hypothesis.

The present study also adapted the parent version of the Racial, Ethnic, and Cultural Socialization measure (Johnston et al., 2007, adapted from Hughes & Chen, 1997) to create adolescent report of parent and peer ethnic socialization. As a result, the wording in adolescent version of parent and peer socialization scales was similar, and this similarity likely accounted for some of correlation that was not captured in analyses. Future research should use an adolescent-driven measure of parent and peer socialization. Recent research, however, has indicated that adolescent report of peer behaviors may be under or over estimated (Rivas-Drake, et al., 2017; Yip et al., 2013).

More research is needed to refine measurements of ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development to account for demographic variations among ethnic minority populations. The study only explored the developmental process aspects related to ethnic identity development (i.e., exploration and resolution) instead of content aspect (i.e., affirmation, ideology). Transracial, transnational adopted youth’s paradoxical experience of being both a member of the dominant White majority and an ethnic minority may complicate the process of ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development. For example, adopted adolescents’ daily ethnic socialization practices usually consist of less culture-specific events, but adopted adolescents are reminded of their ethnic difference when they attend summer culture camp. Additionally, adopted adolescents may also experience the stigma of adoption (Lee, 2010). The study conceptualized parental and peer ethnic socialization as similar processes; however, adopted adolescents may engage in different ethnic socialization practices with peers than with their adopted parents. Similarly, peer ethnic socialization was measured using an adapted version of the parent ethnic socialization measure but other aspects of peer socialization may shed additional insight into ethnic identity development. It should also be noted that the race and ethnicity of the adoptees’ peers are not reported in the study, but past research suggests intraracial/intraethnic peer relationships may offer distinct benefits to ethnic identity development (Syed & Juan, 2012). Future studies should explore the potential implications of intraracial/intraethnic friendships with regard to ethnic identity development.

Conclusion

The study extends current knowledge regarding the ways in which ethnic socialization contribute to ethnic identity development among transracially, transnationally adopted individuals. Discrepancy between adoptive parents and adolescents were found – parents reported higher levels of parental ethnic socialization than adolescents. Additionally, parental ethnic socialization decreased as adopted youth entered adolescence. Further, transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents reported higher parental ethnic socialization than peer socialization. Last, the positive relationships between parental ethnic socialization in childhood and ethnic identity resolution in adolescence were indirectly associated with both parental ethnic socialization and peer ethnic socialization during adolescence. There was partial evidence to support the indirect pathways among parental ethnic socialization in childhood, peer ethnic socialization, and ethnic identity exploration. The study demonstrates the cultural experiences of transracial, transnational adopted individuals and illustrates the importance of longitudinal and multi-informant methodology.

Appendix

Table 1.

Descriptives and Correlations for the Total Sample (n = 116)

| Variables 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Par ES (P) | 1 | 3.09 | .75 | ||||||

| 2. T2 Par ES (P) | .633*** | 1 | 2.80 | .80 | |||||

| 3. T2 Par ES (A) | .431*** | .363*** | 1 | 2.32 | .84 | ||||

| 4. T2 Peer ES (A) | .319** | .262** | .636*** | 1 | 1.79 | .73 | |||

| 5. T2 EI-E (A) | .330*** | .341*** | .617*** | .452*** | 1 | 2.41 | .72 | ||

| 6. T2 EI-R (A) | .050 | .143 | .309** | .376*** | .530*** | 1 | 3.07 | .76 | |

| 7. Child Age | −.028 | −.116 | −.037 | .118 | −.014 | .003 | 1 | 9.44 | 1.66 |

| 8. Education | .228* | .093 | .236* | .048 | .125 | .111 | −.241** | 5.28 | 1.16 |

Notes.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, Par = Parent, ES = Ethnic socialization, EI-E = Ethnic identity – exploration, EI-R = Ethnic identity – resolution, (P) = Reported by parents, (A) = Reported by adolescents.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Path Estimates for Direct and Indirect Effects

| Paths | Model 1 Exploration |

Model 2 Exploration |

Model 3 Resolution |

Model 4 Resolution |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| T1ParES → T2ParES | .69*** | .07 | .44*** | .11 | .69*** | .07 | .44*** | .11 |

| T1ParES → T2PeerES | .31** | .11 | .31** | .11 | .31** | .11 | .31** | .11 |

| T2ParES ↔ T2PeerES | .04 | .04 | .30*** | .06 | .04 | .04 | .30*** | .06 |

| T1ParES → EI | .09 | .10 | .10 | .07 | −.19 | .13 | −.12 | .10 |

| T2ParES → EI | .19 | .11 | .47*** | .08 | .15 | .12 | .12 | .11 |

| T2PeerES → EI | .39*** | .08 | .08 | .10 | .41*** | .09 | .35** | .11 |

| Indirect effects for original models | ||||||||

| T1ParES → T2ParES → EI | .13 | .08 | .21** | .07 | .10 | .08 | .05 | .05 |

| T1ParES → T2PeerES→ EI | .13** | .05 | .03 | .03 | .13** | .05 | .10** | .05 |

| T1ParES → T2ParES → T2PeerES → EI | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 |

| Indirect effects for alternative models | ||||||||

| T1ParES → EI → T2PeerES | .14** | .05 | .13** | .05 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .03 |

| T1ParES → EI → T2ParES → T2PeerES | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 |

| T1ParES → EI → T2PeerES→ T2ParES | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 | < .01 |

Notes.

p < .01;

p < .001.

T1 = Time 1, T2 = Time 2, Par = Parent, ES = Ethnic socialization, EI = Ethnic identity, β = Unstandardized path estimates, SE = Standard error.

Footnotes

The KAD dataset includes transracially, transnationally adopted children between the ages of 7 and 20. The current study examined children who were between the ages of 7–12 in 2007. Other studies have examined adolescents between the ages of 13–20 in 2007 (Hu et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2015). These studies used data from the same dataset, but different age cohorts.

Ethnic identity homophily occurs when pairs of peers share similar levels of ethnic identity (Syed & Juan, 2012).

References

- Barn R. ‘Doing the right thing’: transracial adoption in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2013;36:1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.770543. [Google Scholar]

- Basow SA, Lilley E, Bookwala J, McGillicuddy-DeLisi A. Identity Development and Psychological Weil‐Being in Korean‐Born Adoptees in the US. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(4):473–480. doi: 10.1037/a0014450. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM. Adjustment to adoption: A psychosocial perspective. Clinical Psychology Review. 1987;7:25–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(87)90003-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Alabi BO, Huynh VW, Masten CL. Ethnicity and gender in late childhood and early adolescence: Group identity and awareness of bias. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:463. doi: 10.1037/a0021819. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caltabiano NJ. Perceived differences in ethnic behavior: A pilot study of Italo-Australian Canberra residents. Psychological Reports. 1984;55:867–873. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1984.55.3.867. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW, Chen KH, Dornbusch SM. Theory and observation in cultural transmission. Science. 1982;218:19–27. doi: 10.1126/science.7123211. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7123211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederblad M, Höök B, Irhammar M, Mercke AM. Mental health in international adoptees as teenagers and young adults. An epidemiological study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40(8):1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall M. The determinants of religious behavior: A theoretical model and empirical test. Social Forces. 1989;68:572–592. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579261. [Google Scholar]

- Docan-Morgan S. Korean adoptees’ retrospective reports of intrusive interactions: Exploring boundary management in adoptive families. Journal of Family Communication. 2010;10:137–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431003699603. [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman W. Adjustments of transracially and inracially adopted young adults. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2000;17:165–183. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007531829378. [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman W, Silverman AR. The long-term effects of transracial adoption. The Social Service Review. 1984;58:588–602. https://doi.org/10.1086/644240. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR. Where is the child’s environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological review. 1995;102:458. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.458. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelfarb HS. Agents of religious socialization among American Jews. Sociological Quarterly. 1979;20:447–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1979.tb01230.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Abrams D, Patel Y. Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and occupational aspirations of Indian and Anglo-Saxon British adolescents. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1987;113:487–508. DOI not available. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu AW, Anderson KN, Lee RM. Let’s talk about race and ethnicity: Cultural Socialization, parenting quality and ethnic identity development. Family Science. 2015;6:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2015.1081007. [Google Scholar]

- Hu AW, Kim OM, Lee JP, Lee RM. Conversations about ethnicity and discrimination: Who matters more? Parents vs. friends. Symposium presented at the 2012 American Psychological Association convention; Orlando, Florida. Aug, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Bachman MRD, Fuligni A. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. Tuned in or tuned out: Children’s interpretations of parents’ racial socialization messages; pp. 591–610. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:200–214. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0104_4. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. The nature of parents’ race-related communications to children: A developmental perspective. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda C, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 1999. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:981–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00981.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rivas D, Foust M, Hagelskamp C, Gersick S, Way N. How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed-methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization processes in ethnically diverse families. In: Quintana S, McKown C, editors. Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. pp. 226–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Developmental psychology. 2006;42:747. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston KE, Swim JK, Saltsman BM, Deater‐Deckard K, Petrill SA. Mothers’ racial, ethnic, and cultural socialization of transracially adopted Asian children. Family Relations. 2007;56:390–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00468.x. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Witkow MR, Baldelomar OA, Fuligni AJ. Change in ethnic identity across the high school years among adolescents with Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2010;39:683–693. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9429-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9475-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim OM, Reichwald R, Lee R. Cultural socialization in families with adopted Korean adolescents: A mixed-method, multi-informant study. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2012;28:69–95. doi: 10.1177/0743558411432636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558411432636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk HD. Shared fate: A theory of adoption and mental health. London: Collier-Macmillan; New York: The Free Press of Glenco; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Parents’ monitoring knowledge attenuates the link between antisocial friends and adolescent delinquent behavior. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2008;36:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9178-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JP, Lee RM, Hu AW, Kim OM. Ethnic identity as a moderator against discrimination for transracially and transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2015;6:154–163. doi: 10.1037/a0038360. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. The transracial adoption paradox history, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist. 2003;31:711–744. doi: 10.1177/0011000003258087. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000003258087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Parental perceived discrimination as a postadoption risk factor for internationally adopted children and adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:493. doi: 10.1037/a0020651. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Grotevant HD, Hellerstedt WL, Gunnar MR. Cultural socialization in families with internationally adopted children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:571. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.571. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Yoo HC. Structure and measurement of ethnic identity for Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:263–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.263. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate behavioral research. 2004;39(1):99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massati RR, Vonk EM, Gregoire TK. Reliability and validity of the transracial adoption parenting scale. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;14:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731503257807. [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Porter MR, Thompson LW, Allen JP. Apples and oranges: Divergent meanings of parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental influence. The Journal of early adolescence. 2008;28:206–229. doi: 10.1177/0272431607312768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431607312768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis H, Livingston S, Ryan S, Howard JA. Beyond culture camp: Promoting healthy identity formation in adoption. New York: Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute; 2009. Nov, Retrieved from http://www.adoptioninstitute.org/publications/200911BeyondCultureCamp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behavior genetics. 2007;37(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus. Statistical analysis with latent variables. 2007 Version, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JZ, Ecklund EH. Negotiating Continuity: Family and Religious Socialization for Asian Americans. The Sociological Quarterly. 2007;48:93–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00072.x. [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Sarkar M. Parents’ attitudes toward heritage language maintenance for their children and their efforts to help their children maintain the heritage language: A case study of Korean-Canadian immigrants. Language, Culture and Curriculum. 2007;20:223–235. https://doi.org/10.2167/lcc337.0. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychological bulletin. 1990;108:499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh E. Transnational Korean Adoptees: Adoptee Kinship, Community, and Identity. Journal of American Ethnic History. 2013;32:89–93. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerethnhist.32.2.0089. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, Yip T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child development. 2014;85:40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor A, Schaefer D, Medina M. Ethnic-racial identity and friendships in early adolescence. Child Development. 2017 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojewski JW. A typical American family? How adoptive families acknowledge and incorporate Chinese cultural heritage in their lives. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2005;22:133–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-005-3415-x. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Alvarez J, Bachman M, Cameron J, Fuligni A, Garcia Coll C, Rhee E. The development of a sense of “we”: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In: Bennett M, Sani F, editors. The development of the social self. East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794. https://doi.org/10.2307/2547157. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels GM. “Being raised by white people”: Navigating racial difference among adopted multiracial adults. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:80–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00581.x. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Knight GP, Umaña‐Taylor AJ, Rivas‐Drake D, Lee RM. Methodological issues in ethnic and racial identity research with ethnic minority populations: Theoretical precision, measurement issues, and research designs. Child Development. 2014;85:58–76. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12201. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs PH, Heitfield H. International adopters and their children: Birth culture ties. Gender Issues. 2001;19:3–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-001-1005-6. [Google Scholar]

- Selman P. The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century: Global trends from 2001 to 2010. In: Gibbons J, Rotabi K, editors. Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes. Farnham, UK: Ashgate; 2012. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Song SL, Lee RM. The past and present cultural experiences of adopted Korean American adults. Adoption Quarterly. 2009;12:19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926750902791946. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J, Jose PE. The influence of discrepancies between adolescent and parent ratings of family dynamics on the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:858. doi: 10.1037/a0030056. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M. College students’ storytelling of ethnicity-related events in the academic domain. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2012;27:203–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558411432633. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Azmitia M. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:601–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Juan MJD. Birds of an ethnic feather? Ethnic identity homophily among college-age friends. Journal of adolescence. 2012;35:1505–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Allen WR. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates of racial socialization by Black parents. Child development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton-Weaver LC, Burk WJ, Kerr M, Stattin H. Can Parental Monitoring and Peer Management Reduce the Selection or Influence of Delinquent Peers? Testing the Question Using a Dynamic Social Network Approach. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:2057–2070. doi: 10.1037/a0031854. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AG, Lee RM. Perceived ethnic–racial socialization, ethnic identity, and social competence among Asian American late adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:169. doi: 10.1037/a0016400. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986303262143. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Seaton E. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2. [Google Scholar]

- Vonk ME, Lee J, Crolley-Simic J. Cultural socialization practices in domestic and international transracial adoption. Adoption Quarterly. 2010;13:227–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926755.2010.524875. [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Douglass S, Shelton JN. Daily intragroup contact in diverse settings: Implications for Asian adolescents’ ethnic identity. Child Development. 2013;84(4):1425–1441. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DP. Causal modeling predicting psychological adjustment of Korean-born adolescent adoptees. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2001;3:65–82. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v03n03_06. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Kim SS. Community forces, social capital, and educational achievement: The case of supplementary education in the Chinese and Korean immigrant communities. Harvard Educational Review. 2006;76:1–29. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.76.1.u08t548554882477. [Google Scholar]