Abstract

Objectives

Failure to recruit sufficient applicants to general practice (GP) training has been a problem both nationally and internationally for many years and undermining of GP is one possible contributing factor. The aim of our study was to ascertain what comments, both negative and positive, are being made in UK clinical settings to GP trainees about GP and to further explore these comments and their influence on career choice.

Methodology

We conducted a mixed methods study. We surveyed all foundation doctors and GP trainees within one region of Health Education England regarding any comments they experienced relating to a career in GP. We also conducted six focus groups with early GP trainees to discuss any comments that they experienced and whether these comments had any influence on their or others career choice.

Results

Positive comments reported by trainees centred around the concept that choosing GP is a positive, family-focused choice which facilities a good work–life balance. Workload was the most common negative comment, alongside the notion of being ‘just a GP’; the belief that GP is boring, a waste of training and a second-class career choice. The reasons for and origin of the comments are multifactorial in nature. Thematic analysis of the focus groups identified key factors such as previous exposure to and experience of GP, family members who were GPs, GP role models, demographics of the clinician and referral behaviour. Trainees perceived that negative comments may be discouraging others from choosing GP as a career.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that negative comments towards GP as a career do exist within clinical settings and are having a potential impact on poor recruitment rates to GP training. We have identified areas in which further negative comments could be prevented by changing perceptions of GP as a career. Additional time spent in GP as undergraduates and postgraduates, and positive GP role models, could particularly benefit recruitment. We recommend that undermining of GP as a career choice be approached with a zero-tolerance policy.

Keywords: primary care, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Qualitative and quantitative data from both focus groups and end of year survey data.

Responses gained from trainees in Foundation year two and general practice (GP) specialty training.

Surveys and focus groups all rely on retrospective narratives from junior doctors; therefore, time since an experience may reduce the reliability of this data.

Focus groups of GP trainees at the start of their training and further research may be needed into how experiences change throughout training.

No data gathered from the medical student population and further research needed in order to see whether denigration of GP is a problem in this group.

Introduction

General practice (GP) recruitment is of increasing concern internationally. Recent efforts to improve recruitment in the UK have resulted only in slight improvement with training places left unfilled in some regions.1 These low recruitment levels are in the context of the pledge to increase GP training recruitment, with the target of 50% of postgraduate medical training places being allocated to GP.2 However, the proportion of UK medical graduates intending to enter GP is well below this target, with the proportion reducing rather than increasing.3–5

It is of paramount importance, therefore, to address barriers to recruitment and explore the factors that impact on medical students’ and foundation doctors’ (FDs) career aspirations. Career choice intentions of medical students is a complex issue with multiple modifiable and non-modifiable factors reported, such as exposure to specialty, role models, financial reward, prestige and workload.6 7 The situation around GP as a career choice is similarly complex and includes pretraining perceptions, medical school influences and postgraduate factors.8

One area rarely addressed until recently is the issue of undermining of career choices. It has been suggested, based predominantly on anecdotal evidence, that negative comments made to students and trainees may influence career choices. A notable exception was a recent survey of medical students who reported that psychiatry and GP attracted the greatest number of negative comments, which were made by academic staff, doctors and students. This supports a recent report by Health Education England and the Medical Schools Council (HEE/MSC) on raising the profile of GP at medical schools that stated explicitly among its recommendations: ‘work should take place to tackle undermining of GP as a career across all medical school settings including primary care’.8

Denigration of GP has been studied more extensively internationally within other contexts. Analysis of data from the USA has demonstrated fairly high levels of discouragement about, or denigration of primary care, through five decades.9–13 Similarly, Canadian medical students report particular denigration of family doctors and a general feeling of lack of respect between specialities14 15 and Australian students report poor status of GP to be a particular negative factor in relation to future career choice.16

Study of the denigration of GP in the UK has been limited to focusing on career intention9 14 17 18 and many questions remain unanswered.19 First, what comments, both negative or indeed positive, are being made by clinicians about GP as a career choice? Second, why are comments being made, that is, what are the factors underlying these comments? And third, how do the comments influence the eventual career choice of potential GPs? Thus, the aim of our study was to ascertain what comments, both negative and positive, are being made in clinical settings to trainees about GP and to explore these comments and their perceived influence on career choice with trainees who have chosen a career in GP. To our knowledge, no studies previously have sought to address these aims using qualitative and quantitative methods, in the UK or indeed internationally.

Methods

We undertook a mixed method study, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methods, to address the research questions. Although not without its critics,20 we agree with Bryman and others that there is utility and validity in combining both quantitative and qualitative methods in one study.21 22

We asked all FDs and General Practice Specialty Registrars (GPSTs) within one HEE region about comments that they had received regarding GP as a career option, within a pre-existing online, end of post evaluation survey. FDs in the UK are 1 and 2 years postgraduation and GPSTs are at least 2 years postgraduation, some having many more years of experience prior to commencing GP training. Two reminders were sent to trainees to complete the surveys. The following questions were asked:

FDs: So far in your foundation training have you received any specific comments, either positive or negative, regarding GP as a career option? If so, please describe the exact nature of the comments and by whom they were made. This was asked within the annual, regional FD survey in mid-2016 towards the end of their Foundation year 1 or 2.

GPSTs: In this post have you had any specific comments made, either positive or negative, about your choice of career to be a GP? Please provide the exact nature of the comments and by whom they were made. This was asked within their End of Post Feedback Survey in July 2016 (following completion of a 6-month GP or Hospital Training Post).

Comments were reviewed by the research team and classified as negative, positive or mixed. Where classification was unclear or ambiguous, the comments were classified as mixed. A descriptive analysis was undertaken grouping the themes depending on their nature and source, and the number and proportion of comments were presented.

Focus groups

We undertook six focus groups with GPSTs from the two largest GP training programmes in one HEE region. Focus group interviews were conducted by members of the research team using a semistructured interview format to allow participants to elaborate on their experiences. Focus group interviews varied in size from 3 to 14 participants with an average size of eight (total number of participants=49). Each interview lasted approximately 40 minutes and was digitally recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. Two researchers checked the transcripts in order to confirm the accuracy of transcriptions and to ensure that sufficient participant discussion had taken place, with minimal input from the researcher, allowing rich, authentic data to be captured. Participants were asked to describe and recall any comments made to them by primary or secondary care clinicians, at any point in their training, regarding a career choice of GP. They were asked to expand on the comments and discuss similar or contrasting experiences, and whether they felt that the comments had affected their career choice in any way. Thematic analysis, based on the model outlined by Braun and Clarke,23 was carried out by two members of the research team using a mixed deductive and inductive approach. Participants were fully consented and approval was granted by the University Faculty ethical board.

Results

Survey results

There were 780 responses to the survey from 839 FDs (response rate=93%). Two hundred and thirty-two (30%) FDs reported having received comments about GP as a career choice. Ninety-one FDs reported positive comments (12% of responders), 50 reported negative comments (6%) and 56 reported both positive and negative comments (7%).

There were 343 responses to the GPST end of post evaluation from 399 trainees (response rate=86%). One hundred and thirty-eight (40%) GPSTs reported comments during their previous 6 months post. One hundred and fifteen trainees reported positive comments (33% of responders), 15 reported negative comments (4%) and 8 reported both positive and negative comments (2%).

Table 1 displays the types of comments reported by FD and GPST doctors. The most common types of positive comment were the generic statement ‘you would make a good GP’ (predominantly made to GPSTs; GPSTs perceived this as a positive comment, but it could be argued that this is not necessarily the case), work–life balance issues, the view that the GP training programme was good (predominantly made to FDs) and the variety of the job. Workload was the most common negative comment made to FDs. Other comments were related to it being a wasted career, an easy choice, boring and stressful.

Table 1.

Comments about GP as a career by theme

| Theme | n (FD) | % (FD)* | n (GPST) | % (GPST)* |

| Positive | ||||

| Work–life balance | 20 | 30 | 14 | 23 |

| Good training programme | 16 | 24 | 5 | 8 |

| Variety | 6 | 9 | 5 | 8 |

| Special interests | 4 | 6 | – | – |

| Recruitment crisis-easy to get job | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| Flexible | 4 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Continuity of care | – | – | 3 | 5 |

| Less stress | 1 | 2 | – | – |

| Lifestyle | 1 | 2 | – | – |

| Short training | 1 | 2 | – | – |

| Pay | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Holistic | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Negative | ||||

| Workload | 25 | 34 | 2 | 9 |

| A waste | 6 | 8 | 3 | 14 |

| ‘Easy choice’ | 5 | 7 | 4 | 18 |

| Boring | 6 | 8 | 2 | 9 |

| Stress | 6 | 8 | 2 | 9 |

| Bad referrals | 6 | 8 | – | – |

| Paperwork | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Why be a GP? | 1 | 1 | 3 | 14 |

| Trivial patient problems | – | – | 3 | 14 |

| A few GPs give the profession a bad name | – | – | 2 | 9 |

| Recruitment crisis | 2 | 3 | – | – |

| Training scheme | 2 | 3 | – | – |

| Blame environment | 2 | 3 | – | – |

| Time constraints | 2 | 3 | – | – |

| E-portfolio† | 1% | – | – | |

| QOF‡ | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Complaints | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| ‘For those who can’t do anything else’ | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Media opinion | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Isolating | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Uncertain future | 1 | 1 | – | – |

| Ambiguous | ||||

| ‘You would make a good GP’ | 9 | 14 | 28 | 47 |

*Percentages are based on the number of comments reported by that group of trainees; that is, the denominator is the number of positive or negative comments in total for that group of trainees. Many trainees reported hearing positive and/or negative comments but did not expand further.

†E-portfolio: GPSTs in the UK are required to collect evidence of their learning in an e-portfolio.

‡QOF: Quality and Outcomes Framework: A system of performance payment for GPs in the UK.

FD, foundation doctors; GPST, General Practice Specialty Registrar; GP, General Practitioner.

Positive and negative comments were also grouped by the role of the commentator (table 2). The majority of positive comments were made by GPSTs, followed by GPs. In contrast, the majority of negative comments were made by hospital clinicians.

Table 2.

Comments about GP as a career by commentator

| Commentator | n (FD) | % (FD)* | n (GPST) | % (GPST)* |

| Positive | ||||

| GPSTs | 60 | 57 | 4 | 4 |

| GPs | 23 | 22 | 35 | 31 |

| Consultants | 10 | 10 | 29 | 26 |

| Junior/middle grade hospital doctors | 9 | 9 | 25 | 22 |

| Nursing staff | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Patients | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | – | – | 11 | 10 |

| Negative | ||||

| Junior/middle grade hospital doctors | 29 | 39 | 6 | 22 |

| Consultants(hospital doctors) | 20 | 27 | 8 | 30 |

| GPs | 11 | 15 | 3 | 11 |

| GPSTs | 9 | 11 | – | – |

| Nursing staff | 6 | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| Patients | – | – | – | – |

| Other (non-clinical staff) | – | – | 7 | 26 |

*Percentages are based on the number of comments reported by that group of trainees; that is, the denominator is the number of positive or negative comments in total for that group of trainees. Many trainees reported hearing positive and/or negative comments but did not expand further.

FD, foundation doctors; GPST, General Practice Specialty Registrar; GP, General Practitioner.

Focus group study

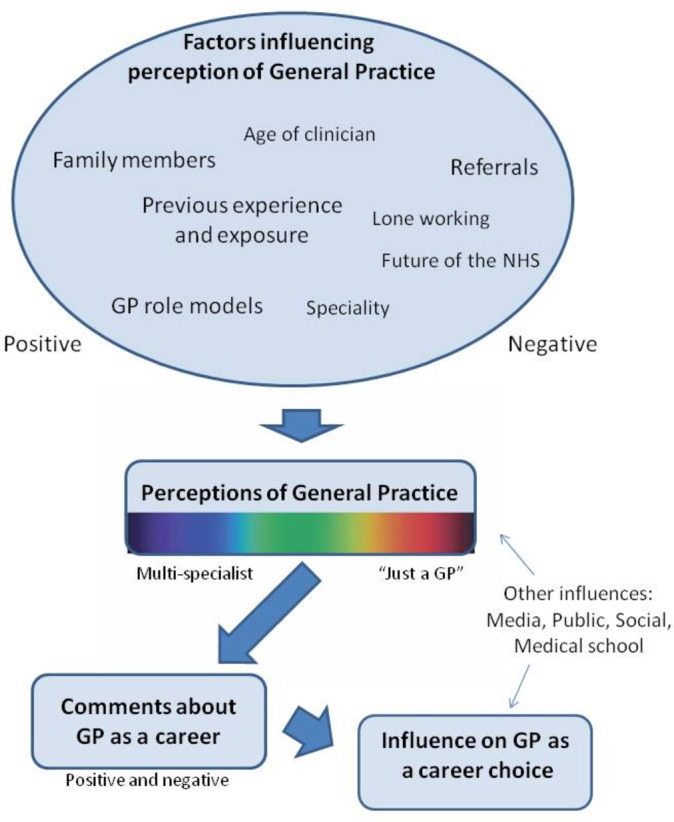

Thematic analysis of the data revealed details of the comments being made and their influencing factors, and a model of how they affect trainees emerged (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors influencing clinicians’ perceptions of general practice (GP). NHS, National Health Service.

Nature of the comments

A picture of the spectrum of clinicians’ perceptions of GP, varying from multispecialists to ‘just a GP’, emerged. Within the hospital setting, particularly in the acute specialities, the job of a GP was viewed as very simple: GPs were perceived as not using or possessing particular skills that hospital doctors had.

"GP’s just being very simple, managing very simple things and you’re not going to be using your brain that much, you’re not going to be using your clinical skills that much it’s just talking and talking". (Senior Registrar being quoted).

The term ‘just a GP’ was frequently reported when trainees were discussing their career option with more senior clinicians. Participants also realised that they would even use this term themselves to describe their future plans. It was linked with the idea that to be a GP was ‘a waste’, with GP seen as inferior to hospital specialities and disregarded as a specialty in its own right:

"you’re too good for GP’ - like that was kind of what he was getting at"

These perceptions were contrasted with comments from other clinicians who had very different views of being a GP, notably of its variety:

"because you are the main community doctor so you are going to deal with so many different things and so you hold a lot of responsibility"

Factors determining clinicians’ perceptions

A number of key factors emerged that appear to underlie clinicians’ perceptions of GP (see figure 1). Some factors were predominantly linked to positive perceptions (previous exposure and experience of GP, family members who were GPs, GP role models), some were linked to both positive and negative perceptions (age and specialty of clinician) and others to predominantly negative perceptions (lone working, uncertain future, referral behaviour).

Previous experience and exposure

Previous exposure to GP, particularly as a FD and medical student, emerged as a predominantly positive influencing factor in selecting GP as a career and influencing clinicians’ perceptions of GP:

"I think everyone should do a foundation rotation in GP, everybody. I think it will help not only people decide if they like it and what to do. But also () having consultants () understand what GPs actually do"

"it’s the people who have of no experience of it, you know personally, or links to it that then give the negative"

Family members

Several participants noted the influence of friends and family members who were GPs on their career choice, but also highlighted the influence of this on hospital doctors’ likelihood to make positive or negative comments:

"And asking for a reference from a consultant whose wife is a GP for GP training, ‘ah yes I’d be delighted to give you a reference, it’s excellent that you’re going to do GP’; But I think that’s coming from his understanding of what it involves"

GP role models

GP role models were reported as consistently positive factors, influencing participants and other clinicians’ perceptions of GP:

"So I think role models is what changes perception, we need people to stand up and help change things"

Age and specialty of clinicians

Differences in specialty, age and stage of clinicians were noted by participants to determine the nature of comments made. Predominantly acute specialities were quoted as making negative comments and older hospital consultants were perceived as more likely than younger registrars to make negative comments:

"working in A&E (Accident and Emergency department) I’ve had the whole ‘you’re wasted in GP' "

"I think it’s that old school kind of consultants who would never have done a GP job in the foundation program training who therefore think things aren’t as they are"

Lone working and uncertain future

Some participants quoted comments from hospital clinicians who perceived GP to be lonely work, without a team, as in the secondary care setting:

"that for a sociable person GP is a lonely job and people would say that as a negative thing"

Several participants reported clinicians making negative comments about choosing GP due to the uncertain future of the National Health Service (NHS):

"anyway my consultant was trying to discourage me from getting onto the GP programme, saying that, it might be appealing now but he doesn’t think that things will remain as such in the future"

Referral behaviour

A further theme that emerged consistently across all focus groups was the relationship between referral behaviour and perceptions of GP and GPs. Participants described numerous experiences of hearing consultants, junior doctors and nurses criticising GPs for ‘rubbish’ referrals. GPs were criticised for failing to independently manage medical problems and were seen as frequently referring, mainly to make their own job a lot easier.

"But in my foundation program I felt that, you know, you work in medical admissions so not even in A&E and it’s like well this is a rubbish referral from the GP, this GP is obviously crap"

" ’this is an inappropriate referral - GP’s are rubbish’: you get that almost I think in every job I’ve done as a hospital doctor and before that when I worked as a midwife or as a nurse"

Influence on career choice

All participants were current GP trainees; therefore, any negative comments experienced had not deterred them from choosing GP. However, some participants reported being initially influenced away from a career in GP:

"I always wanted to do GP in medical school but then when I got to F1 I sort of, you know fell out of love with it a little bit, I think part of that was because there’s so much GP bashing around F1s and in hospital"

"I think one of the reasons why I didn’t just apply for GP straight out was because the people, the medics that I was with were saying, well you’d be wasted you should be doing medicine … and they tipped me away from where I’ve actually ended up, if that makes sense"

Most participants felt that their colleagues who were undecided about GP training could potentially be dissuaded.

"But I can imagine someone who is half and half with a constant barrage of these sort of tongue in cheek comments might you know change their mind"

Other influences

Our study was explicitly focused on the influence of comments made by clinicians towards a career in GP but, not surprisingly given the multifaceted and complex nature of career choice, other potential influences on career choice emerged from the analysis.

Badmouthing of GP on social media, television and in newspapers, was brought up by participants: they reported a lack of awareness of what the job of a GP entails from the general public’s perspective:

"Also everything in the press, not just now but over the last however many years, there is a lot in the press about GP’s and missing this missing that and misrepresentation and I think that as well does impact on people’s perception"

The lack of exposure to GP throughout medical school and the Foundation programme were raised by many participants as potential negative influencing factors. Experience at medical school varied, but the predominant message was that GP was seen as a second class and second choice career:

"I think that’s really difficult in medical school because you spend so little time in general practice or based in general practice … and that kind of just influences your choice as to whether you actually really want to be a GP or not"

"It is even at the beginning when they say ‘so who here wants to do this or whatever' and you’ve got a lecture of 300 and they say ‘so the study showed that 50% of you are going to be GP’s, how many of you are’ and like… ’hands up not very many' and they go ‘ha ha’ and it seems like a bit of a joke somehow"

Discussion

Our study has demonstrated that both negative and positive comments are being made to trainees about a career in GP in the UK and a number of influencing factors have emerged. Many trainees reported positive comments and a significant minority of FDs (19%) and GPSTs (6%), reported negative comments. Qualitative analysis revealed a number of factors that appear to be underlying clinicians’ perceptions of GP (see figure 1): Previous exposure to and experience of GP, family members who were GPs, GP role models, age and specialty of clinician, lone working, the future of the NHS and the influence of referral behaviour.

Quantity of negative and positive comments

The predominance of positive comments is striking and the relative low proportion of trainees reporting negative comments is lower than might have been expected. It is important to note that the trainees are only reporting comments made in their previous placement for GPSTs (6 months) or during Foundation training for FDs (1 or 2 years); some would argue for a zero-tolerance attitude towards undermining, similar to any other form of discrimination.3 24 The larger proportion of negative comments reported by FDs is particularly concerning given that they are yet to commit to a specialty, whereas the increased proportion of positive comments to GPSTs may be understandable as these doctors have already chosen their career path. The nature of the positive comments is also of interest in this group, as half of the comments were praising the doctor that they would ‘make a good GP’, rather than praising the specialty. GPSTs perceived this as a positive comment, but it could be argued that this is not necessarily the case. No similar studies have been reported previously so we are unable to make comparisons, or to comment on whether a similar number of comments, negative or positive, are being made about other medical career choices. The majority of negative comments were made by hospital doctors; there were also negative comments from GPs, whereas GPSTs appear to be championing their specialty.

Nature of the comments

Findings from the survey and the focus group triangulate the nature of comments made and correlate with the limited previous exploratory work in this area.4 25–27 Positive comments centre around the concept that choosing GP is a positive, family-focused choice which facilities a good work–life balance, as supported by previous work18; paradoxically this may have a negative impact on career choice by suggesting that GP is less challenging than other specialties. The frequent negative comments about the workload of GP is perhaps not surprising given the current context of primary care within the NHS in the UK.28 More worrying, are the negative themes around the belief that GP is boring, a waste of training and a second-class career choice. The notion of trainees being ‘just a GP’ has been highlighted in a recent editorial.29 Perceived prestige of specialties has been shown to be an important factor in career choice30 and other studies have demonstrated perceived lack of prestige of GP, with junior doctors portraying it as a choice for those unsuccessful in other areas, with talk of ‘ending up’ or ‘falling back’ on GP.18 31 32

Influencing factors

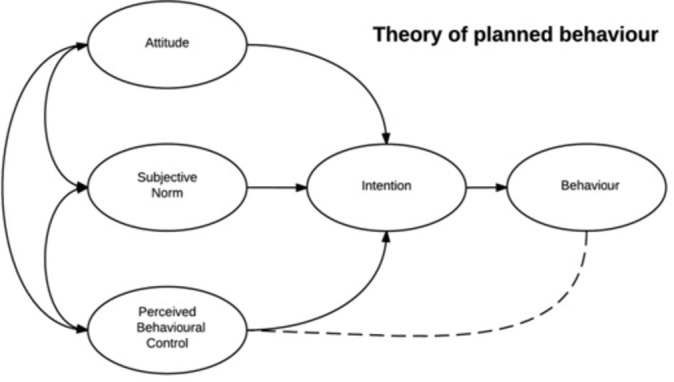

We have proposed an original model (figure 1) to frame the relationship between the factors found to influence clinicians’ perceptions of GP, how this relates to the comments they make and the influence that these can potentially have on trainees’ career choice. This model maps conceptually within the theory of planned behaviour (figure 2),33 a model used to frame a wide variety of behavioural intentions. Perceptions of GP appear to be key, combined with the impact of subjective norms within clinical contexts; both primary and secondary care settings. This behavioural model suggests that to tackle the problem of negative comments about GP as a career choice, we need to address both the factors that influence this perception of GP and the clinical contextual settings, while also addressing individuals’ beliefs that they can change their behaviour.

Figure 2.

Theory of planned behaviour.

The causative factors that our study suggests are influencing perceptions, and therefore comments, about GP may be interlinked: older consultants are suggested in the focus group study to be more likely to make negative comments suggesting that ‘tribalism’ within medicine may be less of a problem with the new generation who have had more exposure to GP as FDs or medical students. Acute specialties may generate more negative comments due to the link with referral behaviour: specialties in which their increased workload is perceived to be due to transfer of work from primary care appear more likely to make negative comments. In contrast, several factors centred around increased understanding of a GPs’ role, appear to make positive comments more likely: having a GP as a family member, GP role models and previous exposure to GP. These are all relatively original findings in the context of the influence they have on perceptions of and comments about, GP by clinicians in training settings. Similarly, the portrayal of GP as a lonely career and the uncertain future of the NHS appear to be influencing factors that are worth confirming and exploring further.

A crucial question is whether denigration of GP does influence career decisions, given that this ‘friendly banter’, as it sometimes portrayed,23 is not a new phenomenon.13 Narratives from our trainees would suggest that the answer is clearly in the affirmative, which would support suggestions from previous studies in other contexts.4 9

Strengths and limitations

Our multimethod study provides triangulation of our findings from two contrasting sources. The high response rate in the survey and relatively large number of participants in the focus group study supports the validity and trustworthiness of the findings. Although the results are from one region of the UK only, there is no theoretical reason why they would not be generalisable, certainly across England and probably the UK. There are some limitations of the study, one being participant recall. We would suggest that prospective studies be undertaken of comments made to medical students and/or trainees. Although the mixed method aids triangulation of our findings these are some differences between the survey and focus groups: For example, the survey questions asked trainees about comments made in their most recent placement only, due to being a component of the trainees postplacement evaluation, whereas the more open and explorative focus group discussions included comments heard throughout their undergraduate and postgraduate training. In addition, focus group participants were GPSTs and we were, therefore, not able to determine whether any potential applicants to GP training had truly been dissuaded due to negative comments.

Implications

Our study has a number of important implications for medical schools, GPs, Secondary care trusts, HEE and the UK NHS as a whole. Most urgently, we have demonstrated that negative comments about GP as a career are being made to trainees in clinical settings and trainees’ perceptions are that these comments do influence career choice. Undermining of GP, and we would extend this to ‘tribalism’ within the medical workforce in general, must be addressed urgently and cohesively within the NHS and training facilities with a ‘zero tolerance’ policy. We would highly endorse the recommendations of the HEE/MSC report within medical schools and extend this to all clinical and postgraduate training settings to tackle undermining of GP as a career choice.8

Our explanatory model (figure 1) would suggest that influencing the factors that lead to individuals’ perception of GP, and the clinical contextual settings in which they work, would potentially address the problem of negative comments about GP as a career choice. In addition, increasing time spent in GP as a medical student and FD, with positive role modelling, would appear to increase the likelihood of trainees becoming GPs.34 35 The move to a single GMC Specialty Register and title of ‘consultant in primary or community care’ may also improve the prestige and respect of GPs among their colleagues.29 Finally, there also appears to be work that GPs can do themselves to raise the profile of their discipline, such as avoiding making undermining comments of their own career.29

Further work/Conclusion

Our study corroborates anecdotal evidence of denigration of GP in clinical settings within the UK and suggests the need to work towards a ‘zero tolerance’ of undermining of career choice. It also reveals several underlying factors influencing the perception of GP and thus, the likelihood of clinicians making negative and positive comments about GP as a career choice. We would strongly recommend that further explorative work and quantitative surveys are undertaken to explore the extent to which our findings are confirmed nationally and internationally, and to confirm to what extent they are discouraging students and trainees from following a career in GP. We have hypothesised an original model, based on motivational theory, to explore the influence of comments made and would recommend that this model be tested in other clinical contexts to confirm and build on our findings. In addition, we would recommend that work be undertaken to explore undermining of hospital medicine by GPs and other clinicians. Badmouthing of all specialities, including GP, whether in the primary or secondary care setting, must be addressed and confronted as a discriminatory issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Newcastle University for funding the focus group study. Thanks to the Postgraduate Primary Care School and Foundation School at Health Education England (across the Northeast and North Cumbria) for collecting the questionnaire evaluation data, and for funding the GP specialty trainees undertaking an education attachment, to the Durham Tees Valley and Northumbria Training Programmes for facilitating access to the General Practice speciality trainees and the participating trainees for their time. Thanks also to Jo Hall for her early help in the project and to Alison Bonavia and Bob Mckinley for advice on drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study proposal was proposed by HA and developed jointly by HA, KB, HC and KM. The focus groups were undertaken by HA and KM and analysed by HA and KM. The survey data were analysed by HC and KB. The paper was written by all authors jointly and all authors approved the final version of the paper. The guarantor for this paper is HA.

Funding: Funding for transcription, publication fees and the cost of focus groups was provided by the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Newcastle University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval granted by Newcastle University Ethics approval committee. Ethics Approval application number: 00911/2015.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data, quotes from focus groups and survey questions which have not been included in the paper, can be requested via the corresponding author.

References

- 1. General Practice National Recruitment Office. Recruitment figures 2015: general practice ST1, 2015. https://gprecruitment.hee.nhs.uk/Portals/8/Documents/Annual%20Reports/GP%20ST1%20Recruitment%20Figures%202015.pdf?ver=2015-12-18-140824-470 (accessed Apr 2017).

- 2. NHS England. General practice forward view, 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf (accessed Apr 2017).

- 3. Baker M, Wessely S, Openshaw D. Not such friendly banter? GPs and psychiatrists against the systematic denigration of their specialties. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:508–9. 10.3399/bjgp16X687169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ajaz A, David R, Brown D, et al. . BASH: badmouthing, attitudes and stigmatisation in healthcare as experienced by medical students. BJPsych Bull 2016;40:97–102. 10.1192/pb.bp.115.053140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lambert TW, Smith F, Goldacre MJ. Trends in attractiveness of general practice as a career: surveys of views of UK-trained doctors. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e238–47. 10.3399/bjgp17X689893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ibrahim M, Fanshawe A, Patel V, et al. . What factors influence British medical students’ career intentions? Med Teach 2014;36:1064–72. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.923560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Querido SJ, Vergouw D, Wigersma L, et al. . Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Med Teach 2016;38:18–29. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1074990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wass V. By choice — not by chance: supporting medical students towards future careers in general practice. London: Health Education England and the Medical Schools Council, 2016. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/By%20choice%20not%20by%20chance%20web%20FINAL.pdf (accessed Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hunt DD, Scott C, Zhong S, et al. . Frequency and effect of negative comments ("badmouthing") on medical students' career choices. Acad Med 1996;71:665–9. 10.1097/00001888-199606000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmes D, Tumiel-Berhalter LM, Zayas LE, et al. . ‘Bashing’ of medical specialties: students' experiences and recommendations. Fam Med 2008;40:400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schafer S, Shore W, French L, et al. . Rejecting family practice: why medical students switch to other specialties. Fam Med 2000;32:320–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stephens MB, Lennon C, Durning SJ, et al. . Professional badmouthing: who does it and how common is it? Fam Med 2010;42:388–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brooks JV. Hostility during training: historical roots of primary care disparagement. Ann Fam Med 2016;14:446–52. 10.1370/afm.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillips SP, Clarke M. More than an education: the hidden curriculum, professional attitudes and career choice. Med Educ 2012;46:887–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pianosi K, Bethune C, Hurley KF. Medical student career choice: a qualitative study of fourth-year medical students at memorial university, newfoundland. CMAJ Open 2016;4:E147–52. 10.9778/cmajo.20150103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tolhurst H, Stewart M. Becoming a GP-a qualitative study of the career interests of medical students. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:204–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erikson CE, Danish S, Jones KC, et al. . The role of medical school culture in primary care career choice. Acad Med 2013;88:1919–26. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e768–75. 10.3399/bjgp16X687049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alberti H, Merritt K. Confronting the bashing: fundamental questions remain. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:604–5. 10.3399/bjgp16X688081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guba EG. Lincoln. Fourth generation evaluation: Sage, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bryman A. Social research methods: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Illing J. Thinking about research: frameworks, ethics and scholarship Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice, 2010:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McDonald P, Jackson B, Alberti H, et al. . How can medical schools encourage students to choose general practice as a career? Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:292–3. 10.3399/bjgp16X685297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edgcumbe DP, Lillicrap MS, Benson JA. A qualitative study of medical students’ attitudes to careers in general practice. Int J Med Educ 2008;19:65–73. 10.1080/14739879.2008.11493651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans J, Lambert T, Goldacre M. GP recruitment and retention: a qualitative analysis of doctors' comments about training for and working in general practice. Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract 2002;83:1–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Firth A, Wass V. Medical students’ perceptions of primary care: the influence of tutors, peers and the curriculum. Int J Med Educ 2007;18:364–72. 10.1080/14739879.2007.11493562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Royal College of General Practitioners. Patient safety implications of general practice workload, 2015. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/fatigue-in-general-practice.aspx (accessed apr 2017).

- 29. Obe VW, Gregory S. Not ’just' a GP: a call for action. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:148–9. 10.3399/bjgp17X689953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Curtis-Barton MT, Eagles JM. Factors that discourage medical students from pursuing a career in psychiatry. Psychiatrist 2011;35:425–9. 10.1192/pb.bp.110.032532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Petchey R, Williams J, Baker M. ’Ending up a GP': a qualitative study of junior doctors' perceptions of general practice as a career. Fam Pract 1997;14:194–8. 10.1093/fampra/14.3.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Merrett A, Jones D, Sein K, et al. . Attitudes of newly qualified doctors towards a career in general practice: a qualitative focus group study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e253–9. 10.3399/bjgp17X690221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ajzen I. From intentions to action: a theory of planned behavior : Kuhl J, Beckman J, Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer, 1985:11. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alberti H, Randles HL, Harding A, et al. . Exposure of undergraduates to authentic GP teaching and subsequent entry to GP training: a quantitative study of UK medical schools. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e248–52. 10.3399/bjgp17X689881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marchand C, Peckham S. Addressing the crisis of GP recruitment and retention: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e227–37. 10.3399/bjgp17X689929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.