Abstract

Objectives

Physical activity is fundamental in diabetes management for good metabolic control. This study aimed to identify barriers to performing leisure time physical activity and explore differences based on gender, age, marital status, employment, education, income and perceived stages of change in physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes in Oman.

Design

Cross-sectional study using an Arabic version of the ‘Barriers to Being Active’ 27-item questionnaire.

Setting

Seventeen primary health centres randomly selected in Muscat.

Participants

Individuals>18 years with type 2 diabetes, attending diabetes clinic for >2 years and with no contraindications to performing physical activity.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Participants were asked to rate how far different factors influenced their physical activity under the following categories: fear of injury, lack of time, social support, energy, willpower, skills, resources, religion and environment. On a scale of 0–9, barriers were considered important if scored ≥5.

Results

A total of 305 questionnaires were collected. Most (96%) reported at least one barrier to performing leisure time physical activity. Lack of willpower (44.4%), lack of resources (30.5%) and lack of social support (29.2%) were the most frequently reported barriers. Using χ2 test, lack of willpower was significantly different in individuals with low versus high income (54.2%vs40%, P=0.002) and in those reporting inactive versus active stages of change for physical activity (50.7%vs34.7%, P=0.029), lack of resources was significantly different in those with low versus high income (40%vs24.3%, P=0.004) and married versus unmarried (33.8%vs18.5%, P=0.018). Lack of social support was significant in females versus males (35.4%vs20.8%, P=0.005).

Conclusions

The findings can inform the design on physical activity intervention studies by testing the impact of strategies which incorporate ways to address reported barriers including approaches that enhance self-efficacy and social support.

Keywords: physical activity, type 2 diabetes, primary health care, barriers, oman, general diabetes, public health, sports Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Barriers to performing leisure physical activity for adults with type 2 diabetes were investigated in Oman, where prevalence of both diabetes and physical inactivity is high.

Questions on possible barriers to performing physical activity linked to religion and environment were included.

The tool used in this study was an English to Arabic language translated questionnaire that may have affected the validity of questions.

Introduction

Oman is located in Southwest Asia on the Southeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula. Similar to its neighbouring countries (United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait), Oman has witnessed enormous economic advancement in recent decades, along with significant increases in non-communicable diseases including a rising prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes prevalence in Oman has increased from 8.3% in 1991 to 12.3% in 2008, and recent estimates are in the order of 14.8%, exceeding global rates.1 2 WHO has indicated that physical inactivity is one of the top 10 leading global causes of mortality and disability worldwide, and the principal cause for approximately 27% of diabetes and approximately 30% of ischaemic heart disease.3 In Oman, it has been reported that almost 70% of the population are physically inactive (daily activity of ≤10 min).4 This raises concerns regarding the impact these high levels of physical inactivity may be having on lifestyle-related chronic diseases including diabetes on healthcare expenditures and overall population health.5

The protective effects of physical activity (PA) in the management of diabetes, specifically type 2 diabetes (T2D), have been widely reported.6 7 WHO recommends at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA or 75 min of vigorous PA/week.8 However, >60% of patients with diabetes in Western countries do not meet the recommended levels of PA.9 10 The Oman World Health Survey (OWHS) 2008 reported that in Oman only 15% of patients with diabetes (98% of them with T2D) met PA recommendations using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ).2

The importance of leisure time PA in meeting PA recommendations is consistently11 associated with reduced mortality risks (20% to >37% risk reduction) and favourable cardiovascular outcomes.12 This relationship appears to have a dose–response effect where the upper threshold for mortality benefit occurs at three to five times the leisure PA recommendations of 7.5 to <15 MET hours/week.12 No clear association is observed for occupational or travel PA.13

Theoretical models underpinning effective interventions to promote personalised PA (contents, methods and approaches) should focus on benefits and ways to overcome barriers to PA.14 Literature to date mainly from Western countries has reported a number of potential barriers to performing PA in adults with diabetes. These include lack of time,15–18 physical constraints including pain,19 lack of knowledge and limited facilities.20 Differences in reporting barriers to PA have been noted across genders, age groups, environments, cultures and disease status. Female gender, increasing age, unsafe neighbourhoods, being overweight and being a smoker increased the odds of reporting barriers to PA among migrant populations like African-Americans, South Asian British and Mexican Americans.21–23 In the Arab countries, modest evidence on barriers to PA in both the general population and in adults with T2D suggests that lack of time, coexisting diseases and adverse weather conditions14 24–29 are the main factors. Moreover, the climate in this region may be a drawback to meeting recommended levels of PA due to high temperatures during the day, particularly in the sandy/desert areas. During the summer months, these countries including Oman experience major heat waves (>40° C) and humidity levels that could reach 90%.

The current study aimed to identify barriers to performing leisure time PA in adults with T2D in Oman and the distribution of barrier scores across different socio-demographic characteristics and perceived stages of change in PA.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This cross-sectional interview-based study was part of a larger study that examined correlates of PA and sitting time in adults with T2D, and barriers to leisure PA in the same population. Results regarding the PA patterns of the population using the GPAQ are reported elsewhere.30 This current paper identified barriers to performing leisure PA expressed by Omani adults with T2D using adapted questions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) questionnaire31 conducted in April/May 2015 in Muscat (urban communities). Reporting of this study follows the guidelines for strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology.32

All patients with T2D attending their routine diabetes clinics in 17 randomly selected primary healthcare centres in Muscat were approached to take part in the study. Inclusion criteria were age >18 years and being followed up in a diabetes clinic for >2 years and ability to provide informed consent. For illiterate participants, informed consents were taken from their spouse, son, daughter or other close family member. Participants with type 1 diabetes, newly diagnosed (<6 months) or who had difficulty in performing any PA, including history of myocardial infarction of <6 months and multiple organ failure, were excluded.

Data sources/measurement

In addition to recording physiological data (body mass index (BMI), medication, duration of diabetes, blood pressure (BP), lipid profile and comorbidities coinciding with diabetes) from the electronic health system, a multisection questionnaire with a range of answers in closed format was administered by a trained interviewer. The following information was collected.

Socio-demographic data

Included gender, age, marital status, education, household income and employment.

Perceptions on stage of change in PA

Based on the trans-theoretical theory of behaviour change,33 subjects were asked to identify their perceived stage of change in PA. Participants were to select ‘maintenance stage’ if they were participating in moderate PA five or more times per week or in vigorous activity three to five times per week longer than six consecutive months or select ‘action stage’ if <6 months. ‘Preparation stage’ was selected by subjects who were thinking about starting exercise such as walking in the near future or doing vigorous activity less than three times per week or moderate activity less than five times per week. Contemplation stage ‘getting ready’ was selected by subjects who were thinking about starting exercise or walk in the next six months. Subjects who were not thinking about starting any PA in the near future selected precontemplation stage ‘not ready’.

CDC questionnaire on barriers to leisure PA

An English to Arabic-translated CDC questionnaire ‘Barriers to Being Active’ was used in a study in Saudi Arabia14 with 21 questions on seven barriers (lack of time, lack of social support, lack of energy, lack of willpower, fear of injury, lack of skill and lack of resources). Permission to use the questionnaire was obtained from the lead author on 24 November 2014 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2813614/figure/F0001/). However, in that tool no statements on religion or environment as possible barriers to PA were included. To address this gap and to formulate robust items on these topics, we undertook several procedures. Literature search was conducted to identify possible content for the new items from similar studies in neighbour countries with similar socio-economical characteristics.28 29 Potential religious barriers considered questions on religious beliefs restricting PA, accepted clothing for PA and religious perceptions on PA.14 25 26 Potential environmental barriers included questions on extreme weather conditions, PA in summer time and availability of appropriate environment for PA.16 25 Content and face validity of the questionnaire were assessed by our investigatory team and draft questions were then discussed with a sample of patients prior to field testing and adjustments were made to ease comprehension and ensure translation to Arabic was appropriate.

A set of three related questions (total of 27 questions) presented in random order within the questionnaire represented one barrier category. A scoring system31 was used to indicate how likely each statement/item was considered to be a barrier (very likely=3, somewhat likely=2, somewhat unlikely=1, very unlikely=0). Scores of the three theme-related questions were added up to provide a total for each category of barriers. Possible scores for each barrier category ranged from 0 to 9. A score of ≥5 was considered as an important barrier to overcome.31 A copy of the used (Arabic and English) questionnaire can be found in online supplementary materials 1 and 2.

To ensure common understanding and acceptability, an interview recording was undertaken in Muscat in 25 randomly selected adult with T2D (population of interest) outside the sampled health centres of the study. Results were discussed and reviewed by the investigation team and an independent statistician.

Based on the data from the current study, the scale quality (27-item study questionnaire) including internal consistency reliability measures was investigated through the use of factor analysis using SPSS V.22 and supported by McDonald’s coefficient omega using the free and open source R.34 35

Study size

Power analysis was performed to estimate the prevalence of meeting PA recommendations in adult population with T2D in a parallel study conducted in the same population.30 We assumed that meeting PA recommendation is at least in part facilitated by reporting fewer barriers to PA36 and used an estimated 15% prevalence of adequate PA in patients with diabetes, as reported in the 2008 OWHS.37 Using 95% confidence limits, a response rate of 80%, a precision of ±4% and smallest expected frequency of 15%, the calculated sample size was ~300 participants across primary health centres in Muscat region, the capital of Oman.

Training

A multidisciplinary team of two nurses, one senior dietician, one medical orderly and two doctors were recruited for data collection. A 1-day training on administration of the questionnaire was delivered by the national focal point on PA in Oman Ministry of Health. Data entry, cross-checking and cleaning were done through Epi Info 7 by an independent personnel. Entered data were transferred to SPSS V.22 for analysis and subsequent results.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were expressed as percentages and mean (SD), median (quartiles) to describe the study sample characteristics. Sum of scores from the three related questions per category (range from 0 to 9) were expressed as median, lower quartile (LQ), and upper quartile (UQ). Correlations between the sum of scores of the nine barrier categories were tested. Furthermore, data were dichotomised to scores <5 and ≥5 to determine the highly reported barriers as advised in the CDC questionnaire and practised in a study in Saudi Arabia.31 χ2 analysis was carried out to identify the distribution of the high barrier scores (≥5) across the independent socio-demographic factors including gender (male vs female); age (to ensure sufficient power and adequate numbers for further statistical analysis the population was divided by the mean age ≤57 vs <57 years); marital status (currently unmarried vs married); education (those unable to read or write (‘uneducated’) versus those having attended primary school or beyond (‘educated’); household income (<500 vs ≥500 Omani rials (‘OR’)); and employment (unemployed, including those retired vs employed). Self-reported stage of change in PA was expressed as one of two categories: inactive if reporting ‘precontemplation’ or ‘contemplation’ and potentially active if reporting being at ‘preparation’, ‘action’ or ‘maintenance’ stages of PA. Corrected P values (Yate’s continuity) were reported for high barrier scores against the studied independent variables.

Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed to identify composite scores for the components underlying the items/questions in the study scale. A nine-factor solution was used to investigate the contributions of the 27-item/questions to the nine barrier categories.38 Furthermore, factor loading matrix was examined using Oblimin rotation39 where correlations between the extracted components were obtained.

Results

Socio-demographic

Out of 312 patients approached, 305 (98%) completed the questionnaire. Slightly more females were represented in this sample (57.4%) than males. The population was slightly older with mean (SD) age of 57 (10.8) years. Additionally, more than two-thirds being married (78.8%) and just about half unable to read or write (48.9%). More than a third of the study population (39.3%) reported household income of <500 OR (less than national average)40 and the majority (77%) reported unemployment (including retirement). More males than females were educated (70% vs 37%) and employed (45% vs 7%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Selected participants characteristics

| Population characteristics | Total population n=305 (100%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 130 (42.6) |

| Female | 175 (57.4) |

| Age (years) | |

| ≤57 | 155 (51) |

| >57 | 150 (49) |

| Marital status | |

| Currently unmarried | 65 (21) |

| Currently married | 240 (79) |

| Education | |

| Not educated | 149 (49) |

| Educated | 156 (51) |

| Income | |

| <500 OR | 120 (39) |

| ≥500 OR | 185 (61) |

| Employment | |

| Not employed | 234 (77) |

| Employed | 71 (23) |

| Physiological | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | Median (LQ, UQ) 6 (4, 10) |

| Self-reported comorbidities* | |

| Yes | 277 (91) |

| No | 28 (9) |

| Current medication | |

| Antihypertension | 217 (71) |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 189 (62) |

| Oral-hypoglycaemic drugs | 260 (85) |

| Oral-hypoglycaemic drugs with insulin | 75 (25) |

| Diet control | 45 (15) |

| Blood pressure† | |

| Within target (<140/<80) | 237 (78) |

| High (≥140/≥80) | 68 (22) |

| Fasting lipid profile (mmol/L)† | |

| Cholesterol within target (<5.0) | 201 (66) |

| Cholesterol high (≥5.0) | 104 (34) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)† | |

| Healthy weight range (18.5–24.99) | 34 (11) |

| Overweight (>25–29.99) | 118 (39) |

| Obese (>30) | 153 (50) |

| HbA1c (%)† (>48 mmol/mol) | |

| Normal≤7 | 127 (42) |

| High>7 | 178 (58) |

| Self-reported stages of physical activity | |

| Not ready (precontemplation) | 112 (37) |

| Getting ready (contemplation) | 95 (31) |

| Preparation | 46 (15) |

| Action | 14 (5) |

| Maintenance | 38 (12) |

*Reported hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, thyroid dysfunction or any other chronic condition coinciding with diabetes.

†Oman diabetes mellitus management guidelines (2015).41

LQ, lower quartile; OR, Oman rial; UQ, upper quartile.

Physiological status

Median (LQ, UQ) duration of diabetes in this population was 6.0 (4.0, 10.0) years. The majority of the participants had hypertension (n=217, 71%) or/and hyperlipidaemia (n=189, 62%) coinciding with their diabetes. All of them were using antihypertensive or/and lipid-lowering medications as appropriate. More than three-quarters of those taking antihypertensives (78%) and two-thirds of those using lipid-lowering drugs (66%) had BP readings and fasting serum cholesterol within target levels (BP <140/80 mm Hg and fasting serum cholesterol of <5 mmol/L).41 Fifteen per cent (n=45) were controlling their diabetes by diet alone versus 85% (n=260) on oral anti-hypoglycaemic medications, in which 25% (n=75) were additionally on insulin. Mean (SD) BMI was 31.0 (6.0) kg/m2 where 89% (n=271) had BMI >25 kg/m2 in which 50% (n=153) were obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) and 39% (n=118) were overweight (BMI >25–29.99 kg/m2). Glycated haemoglobin HbA1c was >7% (>48 mmol/mol) in more than half of the population (58%), indicating poor diabetes control (table 1).

Self-reported stages of PA

Only 17% (n=52) of participants considered themselves actively participating in regular, moderate or vigorous PA (22% of males vs 13% of females). Of the remainder, the majority reported being ‘not ready’ (37%), ‘getting ready’ (31%) or in ‘preparation’ (15%) (table 1).

CDC questionnaire on barriers to leisure PA

For the 27-item/question scale, McDonald’s coefficient omega was =0.750, indicating moderate reliability of the scale.38 Further, PCA analysis with nine-component solution generally supported the previously found subscales (three questions per barrier category) in barriers to performing PA mainly components 2, 4, 5, 6 and 9 representing fear from injury, environmental barriers, religious barriers, lack of willpower and lack of resources respectively (see online supplementary material 3). However, cross-contributions were evident in four out of the nine extracted components, namely component 1 (lack of willpower, time, energy and skills), component 3 (lack of time and energy), component 7 (lack of social support and skills) and component 8 (lack of social support and energy).

bmjopen-2017-016946supp003.pdf (481.7KB, pdf)

Each of the subscales for the nine studied barriers had good reliability (McDonald’s coefficient omega was =0.900). Based on this, further results are presented using sum scores.

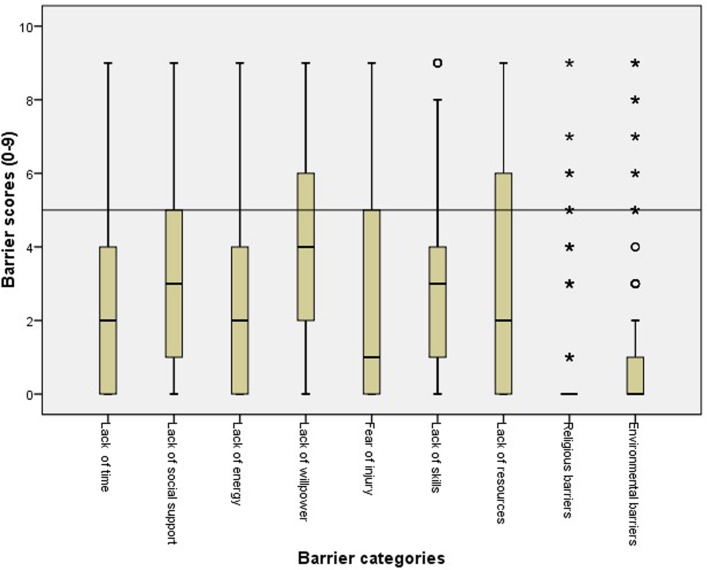

The majority of the population, 97.7% (n=298), reported at least one barrier to performing leisure PA median (LQ, UQ) was 6 (4, 7). Population distributions were not normal across all reported barrier categories. Median sum scores were all <5 as illustrated in figure 1. Except for reporting lack of willpower and lack of resources, 75% of sum scores of other reported barriers were ≤5.

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plots for the reported barrier sum scores of 0–9 (high scores defined as ≥5).

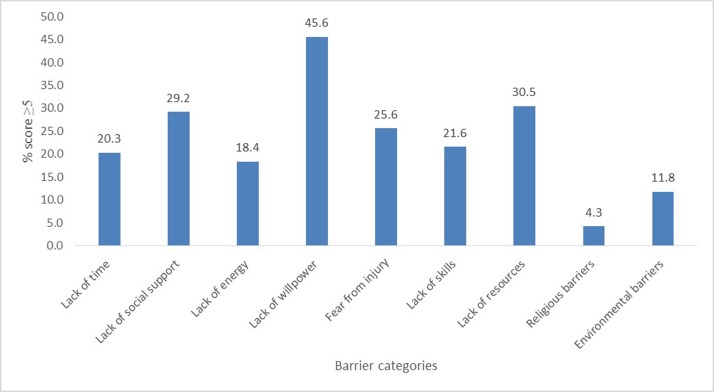

Categorising barrier scores to <5 and ≥5 (significant barrier) highlighted that ‘lack of willpower’ (n=139), ‘lack of resources’ (n=93) and ‘lack of social support’ (n=89) were the most frequently reported ‘significant barriers’ to PA (figure 2). Barriers found to be significant in both males and females were lack of willpower (41.5% males: 48.6% females) and lack of resources (32.3% males: 29.1% females). In addition, lack of time in males (26.9%) and lack of social support in females (35.4%) were also noteworthy (table 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of reported high barrier scores (≥5).

Table 2.

Correlations between sum scores of barrier categories

| Lack of time | Lack of social support | Lack of energy | Lack of willpower | Fear of injury | Lack of skill | Lack of resources | Religious barriers | Environmental barriers | |

| Lack of time | 1.000 | 0.134* | 0.464* | 0.118* | −0.116* | 0.035 | 0.013 | −0.092 | 0.013 |

| Lack of social support | 0.134* | 1.000 | 0.125* | 0.288* | 0.262* | 0.430* | 0.083 | 0.011 | 0.039 |

| Lack of energy | 0.464* | 0.125* | 1.000 | 0.306* | −0.013 | 0.178* | 0.171* | −0.070 | 0.099 |

| Lack of willpower | 0.118* | 0.288* | 0.306* | 1.000 | 0.058 | 0.497* | 0.260* | −0.112 | 0.053 |

| Fear of injury | −0.116* | 0.262* | −0.013 | 0.058 | 1.000 | 0.338* | −0.218* | 0.032 | −0.090 |

| Lack of skill | 0.035 | 0.430* | 0.178* | 0.497* | 0.338* | 1.000 | 0.182* | −0.052 | 0.005 |

| Lack of resources | 0.013 | 0.083 | 0.171* | .260* | −0.218* | 0.182* | 1.000 | 0.038 | 0.281* |

| Religious barriers | −0.092 | 0.011 | −0.070 | −0.112 | 0.032 | −0.052 | 0.038 | 1.000 | 0.007 |

| Environmental barriers | 0.013 | 0.039 | 0.099 | 0.053 | −0.090 | 0.005 | 0.281* | 0.007 | 1.000 |

*P value<0.050.

Correlations between the sum scores of the nine studied barriers were generally weak (R<0.200). Positive and significant correlations of >0.300 were noted among lack of energy with lack of time; lack of skill with lack of social support; lack of energy and lack of willpower; lack of skills with lack of willpower; and fear of injury with lack of skills (table 2). Interestingly, no significant correlations were seen within the religious and environmental barriers except for one weak significant positive correlation between lack of resources and environmental barriers.

Distributions of significant high barrier score (≥5) across the studied socio-demographic factors and self-reported stages of change in PA differed among the nine barrier categories: ‘lack of time’ was frequently highly scored by males, younger adults and those who were married, employed or educated. Additionally, ‘lack of social support’ was highly scored by females and ‘lack of energy’ by employed or educated adults. However, ‘lack of willpower’ was highly scored by individuals with lower income or at inactive stages of PA. Moreover, ‘fear of injury’ was highly scored by older adults, unemployed, uneducated or individuals reporting inactive stages of PA. Furthermore, ‘lack of skills’ was highly scored by females, younger adults and unemployed or uneducated. ‘Lack of resources’, on the other hand, was frequently highly scored by married adults or with lower income. It is notable that the religious and environmental barriers had no significant different distributions across any of the studied factors (table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of high barrier scores (≥5) to leisure physical activity in adult population with type 2 diabetes across socio-demographic variables and self-reported stages of change in physical activity (n=305)

| (%) Scores≥5 | Lack of time | Lack of social support | Lack of energy | Lack of willpower | Fear of injury | Lack of skills | Lack of resources | Religious barriers | Environmental barriers |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male Female Corrected χ2 P value |

26.6 15.4 5.4 0.020* |

20.8 35.4 7.1 0.008* |

21.5 16.0 1.2 0.278 |

41.5 48.6 1.2 0.270 |

24.6 26.3 0.04 0.843 |

13.1 28.0 8.9 0.003* |

32.3 29.1 0.2 0.640 |

3.8 4.6 0.001 0.981 |

10.0 13.1 0.4 0.508 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| ≤57 >57 Corrected χ2 P value |

27.7 12.7 9.7 0.002* |

26.5 32.0 0.9 0.347 |

21.3 15.3 1.4 0.232 |

45.8 45.3 0.0 1.000 |

18.7 32.7 7.1 0.008* |

16.1 27.3 5.0 0.025* |

33.5 27.3 1.1 0.292 |

4.5 4.0 0.00 1.000 |

12.3 11.3 0.0 0.942 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Unmarried Married Corrected χ2 P value |

10.8 22.9 3.9 0.047* |

35.4 27.5 1.2 0.277 |

16.9 18.8 0.0 0.875 |

43.1 46.3 0.1 0.753 |

30.8 24.2 0.9 0.356 |

24.6 20.8 0.2 0.626 |

18.5 33.8 4.9 0.026* |

7.7 3.3 1.4 0.231 |

13.8 11.3 0.1 0.720 |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Unemployed Employed Corrected χ2 P value |

12.4 46.5 37.0 <0.001* |

31.6 21.1 2.4 0.120 |

14.5 31.0 8.8 0.003* |

47.0 40.8 0.6 0.437 |

29.5 12.7 7.2 0.007* |

25.6 8.5 8.5 0.004* |

31.6 26.8 0.4 0.527 |

4.7 2.8 0.1 0.740 |

11.5 12.7 0.0 0.960 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Uneducated Educated Corrected χ2 P value |

11.4 28.8 13.2 <0.001* |

33.6 25.0 2.3 0.129 |

13.4 23.1 4.1 0.042* |

45.6 45.5 0.0 1.0 |

35.6 16.0 14.2 <0.001* |

28.2 15.4 6.6 0.010* |

29.5 31.4 0.1 0.816 |

6.0 2.6 1.5 0.162 |

10.7 12.8 0.1 0.700 |

| Income | |||||||||

| <500 ≥ 500 Corrected χ2 P value |

16.7 22.7 1.3 0.257 |

26.7 30.8 0.4 0.516 |

21.7 16.2 1.1 0.294 |

54.2 40.0 5.3 0.021* |

20.8 28.6 1.9 0.163 |

23.3 20.5 0.2 0.663 |

40.0 24.3 7.7 0.005* |

5.8 3.2 0.6 0.422 |

8.3 14.1 1.8 0.183 |

| Self-reported stages of physical activity | |||||||||

| Not active Active Corrected χ2 P value |

18.4 24.5 1.2 0.276 |

28.5 30.6 0.1 0.808 |

17.9 19.4 0.0 0.873 |

50.7 34.7 6.2 0.012* |

31.9 12.2 12.5 <0.001* |

24.2 16.3 2.0 0.161 |

29.5 32.7 0.2 0.667 |

4.3 4.1 0.00 1.0 |

13.5 8.2 1.4 0.244 |

*Significant at P<0.050.

Discussion

Despite evidence on the effectiveness of meeting PA levels in the management of T2D and associated cardiovascular risk factors,6 7 PA is poorly addressed in routine diabetes care.42 Low PA levels in populations with T2D are consistently reported in Western countries, for example, the USA43 as well as in Arabic-speaking countries, namely Oman, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon.2 44 45 Addressing perceived barriers to performing recommended PA levels in this population is crucial for planning effective PA-promoting interventions.

Within a series of formative studies to inform a culturally congruent PA intervention in diabetes care,46 this study has looked at perceived barriers to performing leisure time PA in an adult population with T2D attending primary care using an adapted CDC questionnaire translated to Arabic language.14

The current findings relating to willpower, resources and social support were also reported as the top three barriers to PA in the Saudi population attending primary care by AlQuaiz.14 In the West, the USA in particular, the strongest reported barriers to PA among adults with T2D were pain (41%), followed by lack of willpower (27%) and poor health (21%).47

In the current study, lack of willpower was significantly highly reported by individuals from low-income households. This finding is similar to a Canadian study which reported a negative association between financial position and on intention to participate in leisure time PA in adult population with T2D in Canada.48 Additionally in a study in the USA, older individuals with low income who were found to be depressed had low participation in social activities and less odds of engaging in PA.49 Nonetheless, more evidence is needed to explain how income alters the willpower for performing leisure PA in Arabic-speaking countries, namely Oman. Comparably, lack of willpower was more likely to be reported by individuals at inactive stages of PA (precontemplation or contemplation stages of PA) than those in active stages. Progressive stages of behavioural change according to the trans-theoretical model were direct correlates to PA in a review article by Trost50 and direct determinants in another by Van Stralen.51 This finding supports the need for programmes to help raise self-willpower/determination through stepped process of behaviour change from inactive (precontemplation) to active stages of PA (action and maintenance).52 Interestingly, fear of injury was the only other reported barrier significantly different between individuals at inactive versus active stages of change in PA. This could be explained by possible physical constraints pertaining to older age49 and existing comorbidities in the current study population triggering fear of injuries associated with PA.

Limited resources including high cost and limited facilities for PA have been reported as significant barriers to PA across different cultures.20 22 In the current study, limited resources were reported as significant by individuals who were married and those with low income. Married individuals could have more financial commitments to their families especially in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries where extended families are common.53 This may alter an individual’s priorities for household income expenditure. Low income was similarly reported as a barrier in a Saudi population, possibly due to the perceived high cost of using PA facilities.14 This may reflect a narrow view on what constitutes PA and a misconception that expensive equipment is required. Hence, irrespective of culture, interventions promoting cost-neutral PA such as walking in populations would be highly desirable to overcome this barrier.46 54

Lack of social support was frequently reported by females in this study. Meeting cultural norms and social expectations related to safety, security and conservative dress mainly for females were reported as barriers to PA in South Asian (Pakistani and Indian) British populations18 21 and populations in Arabic countries such as Qatar.55 Evaluation of interventions to provide the necessary social support and networks to PA specifically for women with T2D, particularly in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, is warranted. Activities including group-based activities and buddying56–58 are worth further investigation.

Other reported barriers such as fear of injury and lack of skills varied across subgroups in particular, older, unemployed and uneducated individuals. Older individuals with T2D are more vulnerable to have poor vision and osteoarthritic changes that may cause fall and injuries.59 Moreover, the negative influence of pain to PA in older population with T2D was reported in Western countries,47 and hence potential barriers to individuals’ participation. These results suggest that programmes to promote PA should be individualised for type, frequency and intensity of PA and incorporate safety measures to prevent PA-induced pain and injuries in older individuals.60

Lack of time, on the other hand, has been a highly cited barrier to PA in the general population as well as populations with diabetes.15–18 21 22 47 61 However, unlike the study by Alquaiz, significant scores for lack of time in this study were higher in males compared with females14 along with a lack of energy, which may be a reflection of the fact that more males than females were educated and employed. This perception of ‘lack of time’, in addition to family and social commitments, may jeopardise their time for PA, especially if individuals were younger and married. This discussion highlights the importance of changing people’s perceptions of PA but also consideration of opportunities in other PA domains, namely work and travel, that could enable individuals with less leisure time to increase overall PA and behaviour.

Factors which are independent of an individual’s decision-making, such as environment and religion, had no significant associations in the current study despite the hot weather during data collection of this study in April/May. These null results may be real or may be due to the wording of the questions and their interpretation. To address these gaps in the literature, a qualitative exploration of possible environmental, including seasonal variations, and religious factors affecting PA performance may be warranted.

Moreover, PCA showed cross-contribution of items/questions within lack of willpower, time, energy and skills indicating doubtful responses. Similarly, inputs from questions on lack of social support and lack of skills and energy were mixed. Future questionnaires on barriers to performing PA, especially in the Arabic-speaking countries, should consider more specific questions.

Additionally, results of this study cannot be generalised across all regions in Oman. More information is required from rural Omani communities where perceptions on PA may be different. Despite the excellent scale reliability measures in the current data, the results cannot be generalised due to possible differences in scale quality across various data.38 Moreover, due to the cross-sectional design of this study, causal inferences cannot be drawn.

Finally, future attempts to explore barriers to PA should equally include work and travel domains to cater for diversities in both PA behaviour and sedentary lifestyle across subgroups of adults with T2D.

Conclusion

This study identified lack of willpower, low resources and low social support (especially in females) as the most common barriers to performing leisure PA. The current findings can be used to inform the design of PA interventions for testing in clinical trials. The specific areas which might be usefully included to address barriers to performing PA are (1) assessment of individuals’ readiness to change, (2) low-cost options for PA resources and social support, (3) approaches aimed at increasing individuals’ understanding of what constitutes PA and (4) methods that are flexible and tailored to the specific needs of subgroups of adults with T2D. In addition, approaches that enhance self-efficacy (and will power) and social support should be included.

bmjopen-2017-016946supp001.pdf (128.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016946supp002.pdf (113.9KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TSA is the principal investigator in charge of the project. SMA, YF, EB, AMC and ASA have all been involved in designing the intervention and the evaluation. TS prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and all other authors have contributed. All authors have critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The Oman Ministry of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Regional Research Committee in Muscat, Oman Ministry of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and approvals from the Oman Ministry of Health.

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes atlas. 7th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015. http://www.diabetesatlas.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al Riyami A, Elaty MA, Morsi M, et al. . Oman world health survey: part 1 - methodology, sociodemographic profile and epidemiology of non-communicable diseases in oman. Oman Med J 2012;27:425–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Physical activity: WHO, 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/ (accessed 21 May 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Badran M, Laher I. Type II Diabetes mellitus in Arabic-speaking countries. Int J Endocrinol 2012;2012:1–11. 10.1155/2012/902873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oman Health Vision 2050, Ministry of Health, Directorate of Planning, 2012.

- 6. Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, et al. . Exercise and type 2 diabetes: American college of sports medicine and the American diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:2282–303. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181eeb61c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Loreto C, Fanelli C, Lucidi P, et al. . Make your diabetic patients walk: long-term impact of different amounts of physical activity on type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1295–302. 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. WHO’s global recommendations on PA for health, 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdf

- 9. Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, et al. . Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012;380:272–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60816-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, et al. . Physical activity in U.S. adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes, 2003. Diabetes Care 2007;30:203–9. 10.2337/dc06-1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. . Exercise and type 2 diabetes: The American college of sports medicine and the American diabetes association: Joint position statement. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e147–e167. 10.2337/dc10-9990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arem H, Moore SC, Patel A, et al. . Leisure time physical activity and mortality: a detailed pooled analysis of the dose-response relationship. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:959–67. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallman DM, Mathiassen SE, Gupta N, et al. . Differences between work and leisure in temporal patterns of objectively measured physical activity among blue-collar workers. BMC Public Health 2015;15:976 10.1186/s12889-015-2339-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. AlQuaiz AM, Tayel SA. Barriers to a healthy lifestyle among patients attending primary care clinics at a university hospital in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med 2009;29:30–5. 10.4103/0256-4947.51818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Egan AM, Mahmood WA, Fenton R, et al. . Barriers to exercise in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. QJM 2013;106:635–8. 10.1093/qjmed/hct075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Husman PM, et al. . Motivators and barriers to exercise among adults with a high risk of type 2 diabetes--a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25:62–9. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00791.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hume C, Dunstan D, Salmon J, et al. . Are barriers to physical activity similar for adults with and without abnormal glucose metabolism? Diabetes Educ 2010;36:495–502. 10.1177/0145721710368326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH. Barriers to regular exercise among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Health Promot Int 2009;24:416–27. 10.1093/heapro/dap031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Labrunée M, Antoine D, Vergès B, et al. . Effects of a home-based rehabilitation program in obese type 2 diabetics. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2012;55:415–29. 10.1016/j.rehab.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Booth AO, Lowis C, Dean M, et al. . Diet and physical activity in the self-management of type 2 diabetes: barriers and facilitators identified by patients and health professionals. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2013;14:293–306. 10.1017/S1463423612000412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hanna L, et al. . ’I can’t do any serious exercise': barriers to physical activity amongst people of Pakistani and Indian origin with Type 2 diabetes. Health Educ Res 2006;21:43–54. 10.1093/her/cyh042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mier N, Medina AA. Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes: perspectives on definitions, motivators, and programs of physical activity. Prev Chronic Dis 2007;4:A24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wanko NS, Brazier CW, Young-Rogers D, et al. . Exercise preferences and barriers in urban African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2004;30:502–13. 10.1177/014572170403000322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Otaibi HH. Measuring stages of change, perceived barriers and self efficacy for physical activity in Saudi Arabia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:1009–16. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.2.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amin TT, Suleman W, Ali A, et al. . Pattern, prevalence, and perceived personal barriers toward physical activity among adult Saudis in Al-Hassa, KSA. J Phys Act Health 2011;8:775–84. 10.1123/jpah.8.6.775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ali HI, Baynouna LM, Bernsen RM. Barriers and facilitators of weight management: perspectives of Arab women at risk for type 2 diabetes. Health Soc Care Community 2010;18:219–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berger G, Peerson A. Giving young Emirati women a voice: participatory action research on physical activity. Health Place 2009;15:117–24. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Al-Kaabi J, Al-Maskari F, Saadi H, et al. . Physical activity and reported barriers to activity among type 2 diabetic patients in the United arab emirates. Rev Diabet Stud 2009;6:271–8. 10.1900/RDS.2009.6.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Serour M, Alqhenaei H, Al-Saqabi S, et al. . Cultural factors and patients' adherence to lifestyle measures. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:291–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alghafri TS, Alharthi SM, Al-Farsi Y, et al. . Correlates of physical activity and sitting time in adults with type 2 diabetes attending primary health care in Oman. BMC Public Health 2017;18:85 10.1186/s12889-017-4643-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Usa CDC. “Overcoming barriers to physical activity”: Centers for disease control and prevention, 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ndep/pdfs/8-road-to-health-barriers-quiz-508.pdf (accessed 16 Jul 2014).

- 32. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies, 2017. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/ (accessed 22 Jan 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Martin SB, Morrow JR, Jackson AW, et al. . Variables related to meeting the CDC/ACSM physical activity guidelines. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:2087–92. 10.1097/00005768-200012000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Crutzen R, Peters G-JY. Scale quality: alpha is an inadequate estimate and factor-analytic evidence is needed first of all. Health Psychology Review 2015:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. R Development Core Team. 2014. http://r-development-core-team.software.informer.com/

- 36. Heiss V, Petosa R. Correlates of physical activity among adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic literature review. Am J Health Educ 2014;45:278–87. 10.1080/19325037.2014.933139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministry of Health Oman. studies DoRa , World health survey report. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol 2014;105:399–412. 10.1111/bjop.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Youngblut JM. Comparison of factor analysis options using the Home/Employment Orientation Scale. Nurs Res 1993;42:122???124–4. 10.1097/00006199-199303000-00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ministry of National Economy. Statistical yearbook. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of National Economy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ministry of Health Oman. centre E : Diabetes management guidelines. Oman: Ministry of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matthews L, Kirk A, Macmillan F, et al. . Can physical activity interventions for adults with type 2 diabetes be translated into practice settings? A systematic review using the RE-AIM framework. Transl Behav Med 2014;4:60–78. 10.1007/s13142-013-0235-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, et al. . Physical activity in U.S. adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes, 2003. Diabetes Care 2007;30:203–9. 10.2337/dc06-1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Al-Nozha MM, Al-Hazzaa HM, Arafah MR, et al. . Prevalence of physical activity and inactivity among Saudis aged 30-70 years. A population-based cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J 2007;28:559–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sibai AM, Costanian C, Tohme R, et al. . Physical activity in adults with and without diabetes: from the ’high-risk' approach to the ’population-based' approach of prevention. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1002–02. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alghafri TS, Alharthi SM, Al-Farsi YM, et al. . Study protocol for "MOVEdiabetes": a trial to promote physical activity for adults with type 2 diabetes in primary health care in Oman. BMC Public Health 2017;17:28 10.1186/s12889-016-3990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thomas N, Alder E, Leese GP. Barriers to physical activity in patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:287–91. 10.1136/pgmj.2003.010553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boudreau F, Godin G. Understanding physical activity intentions among French Canadians with type 2 diabetes: an extension of Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009;6:35 10.1186/1479-5868-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Plow MA, Allen SM, Resnik L. Correlates of Physical Activity Among Low-Income Older Adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2011;30:629–42. 10.1177/0733464810375685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, et al. . Correlates of adults' participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:1996–2001. 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van Stralen MM, De Vries H, Mudde AN, et al. . Determinants of initiation and maintenance of physical activity among older adults: a literature review. Health Psychol Rev 2009;3:147–207. 10.1080/17437190903229462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kirk A, MacMillan F, Webster N. Application of the Transtheoretical model to physical activity in older adults with Type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease. Psychol Sport Exerc 2010;11:320–4. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. GCC statistical center. GCC-statistics, 2010. https://gccstat.org/en/terms-of-use13/10/2016

- 54. Bird EL, Baker G, Mutrie N, et al. . Behavior change techniques used to promote walking and cycling: a systematic review. Health Psychol 2013;32:829–38. 10.1037/a0032078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Donnelly TT, Al Suwaidi J, Al Enazi NR, et al. . Qatari women living with cardiovascular diseases-challenges and opportunities to engage in healthy lifestyles. Health Care Women Int 2012;33:1114–34. 10.1080/07399332.2012.712172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bastiaens H, Sunaert P, Wens J, et al. . Supporting diabetes self-management in primary care: pilot-study of a group-based programme focusing on diet and exercise. Prim Care Diabetes 2009;3:103–9. 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Matthews L. The feasibility, effectiveness and implementation of a physical activity consultation service for adults within routine diabetes care. [Implementation of physical activity services for the management of adults with Type 2 Diabetes]. University of Strathclyde School of Psychological Sciences and Health 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Barrera M, Strycker LA, Mackinnon DP, et al. . Social-ecological resources as mediators of two-year diet and physical activity outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients. Health Psychol 2008;27(2 Suppl):S118–S125. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998;15:539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Borschmann K, Moore K, Russell M, et al. . Overcoming barriers to physical activity among culturally and linguistically diverse older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Australas J Ageing 2010;29:77–80. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Donahue KE, Mielenz TJ, Sloane PD, et al. . Identifying supports and barriers to physical activity in patients at risk for diabetes. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3:A119–A19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016946supp003.pdf (481.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016946supp001.pdf (128.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016946supp002.pdf (113.9KB, pdf)