Abstract

Purpose

We report a case of ophthalmomyiasis interna successfully removed in toto with pars plana vitrectomy.

Observations

An 84-year-old woman with recent close contact with lambs presented with a new floater. Examination revealed subretinal tracks pathognomonic for ophthalmomyiasis and a larva suspended in the vitreous. The larva was successfully removed in toto with pars plana vitrectomy by aspiration through the vitreous cutter.

Conclusions and importance

Aspiration with pars plana vitrectomy can be considered a primary therapeutic modality for botfly larvae suspended in the vitreous. In our case, in toto removal of the larvae reduced the risk of inflammatory reaction.

Keywords: Ophthalmomyiasis interna, Vitrectomy, Oestrus ovis, Sheep botfly

1. Introduction

Ophthalmomyiasis describes infection of the eye by the burrowing larvae of certain fly species. In the United States, most cases are attributed to the larvae of the rodent botfly species Cutebara or Hypoderma,1, 2, 3, 4 but several species of botfly responsible for ophthalmomyiasis in humans have been identified including the cattle, sheep, deer, rodent, and human botflies.5

Most larvae invade the cornea, conjunctiva, or adnexal tissues (ophthalmomyiasis externa).6, 7, 8 Less commonly, the larva may invade the anterior chamber, vitreous, or subretinal space after boring through the ocular cul-de-sac (ophthalmomyiasis interna).1, 2 Patients with ophthalmomyiasis externa may complain of pain, itching, tearing, foreign body sensation, chemosis, and mucopurulent discharge.9 In contrast, patients with ophthalmomyiasis interna may complain of flashes, floaters, linear scotomas, and pain.10, 11

2. Case report

An 84-year-old woman who lives within a major city in the Pacific Northwest presented to her retina specialist with a new floater eight months after participating in a lambing (the assisted birthing of a lamb from an ewe). Her only ocular history was non-neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Her vision was 20/20 in the affected eye. On exam, several criss-crossing hypopigmented atrophic tracks in the retinal periphery were noted as well as an immobile larva suspended in mid-vitreous (Fig. 1). A 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy was performed and the immobile organism was removed without corporeal disruption via aspiration through the vitreous cutter into an attached 3 ml syringe attached to the aspiration line via a 3-way stopcock.

Fig. 1.

(A) Ultra-wide field color fundus photo of the right eye demonstrating peripheral hypopigmented subretinal tracks and a larva in the vitreous anteriorly (white circle). (B) Ultra-wide field fundus autofluorescence photo highlighting the subretinal tracks. (C) Color slit lamp photo of the larva suspended in anterior vitreous. (D) Infra-red image of larva.

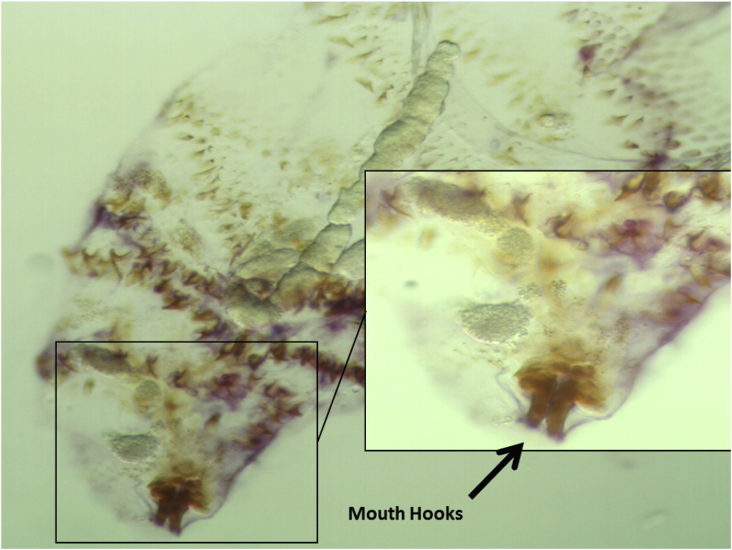

Histopathologic examination disclosed a clear ovaloid structure with eight to ten horizontal segments that taper to a point at both ends. Multiple bands of tiny brown hooks lined the junction between each segment. Protruding from the tapered end of the specimen were two brown terminal hooks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Histological image of the retrieved specimen demonstrating transparent body with tapered ends, mouth hooks, and body spicules.

3. Discussion

Globally, the most common cause of human ophthalmomyiasis is the sheep blotfly Oestrus ovis.12 Adult O ovis flies typically incubate eggs internally until they hatch, then deposit the larvae in the nostrils of sheep or goats. Eggs or larvae may also be deposited on human corneal or conjunctival tissue by contact with an adult fly or the human's own contaminated hand. Farmers, shepherds, or those living in rural areas are most at risk, but infection my also occur in urban dwellers.13, 14, 15 Other risk factors include advanced age, debilitation, ocular wounds and infections, and poor general health.16

On examination, patients with ophthalmomyiasis externa have findings consistent with mucopurulent conjunctivitis 9. In ophthalmomyiasis interna, larvae that invade the subretinal space may travel back and forth across the fundus within the subretinal space, creating characteristic hypopigmented criss-crossing tracks.17 Subretinal hemorrhages may be seen where the tunneling larva disrupts local vasculature. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) may demonstrate hyporeflective spaces between the outer retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), with adjacent hyperreflectivity.18 Larvae that enter the vitreous may leave a vitreous hemorrhage at the retinal exit wound.19 Dead larvae or larval remnants within the vitreous may cause an inflammatory response ranging from mild vitritis to florid veitis,20 endophthalmitis,21 traction retinal detachment,22 or lens dislocation.23 A small, segmented larva with tapered ends and body spicules up to 5 mm in length may be seen on slit lamp exam, in the subretinal space, or suspended in the vitreous body.

In our patient, fundus examination revealed hypopigmented tracks in the retina consistent with a larva tunneling through the subretinal space. It is likely that the larva migrated from the subretinal space into the vitreous cavity, although no holes or breaks in the retina were seen. It is likely that the larva died shortly prior to presentation as there was no evidence of inflammation and the larva appeared intact without signs of decomposition.

Depending on the structural integrity or method of retrieval of intraocular larvae, precise identification of the causative organism is often challenging if not impossible. Based on previous descriptions, the retrieved specimen had morphological features consistent with the first instar of the sheep botfly O ovis,24 although larva of other fly species remain in the differential. O ovis ophthalmomyiasis is typically limited to the external type, but cases of ophthalmomyiasis interna do occur.25 Our patient's history of ovine exposure supports this as the causative organism.

Treatment is centered on timely removal of the larva from the eye to prevent consequent inflammation and other sequelae. If treatment is elected, subretinal larvae may be destroyed by laser photocoagulation. If the larva is within the macula, one may chase it into a safer area before attempting photocoagulation as the larvae exhibit negative phototaxis.12, 13 Those larvae in the vitreous cavity may be removed whole via a pars plana vitrectomy,21, 20 with care taken to remove the larva intact.1 The patient should be carefully observed and promptly treated for development of any inflammatory reaction. For cases in which the larva cannot be isolated or removed, successful treatment with oral Ivermectin and corticosteroids has been reported.26, 4, 27

4. Conclusion

Ophthalmomyiasis may occur in humans with close animal contact, whether they live in rural or urbans areas. Larvae may remain confined to the external tissues of the eye or invade intraocularly, leading to severe inflammation and other dangerous sequelae. Social history and inquiries about animal contact are important in narrowing the differential diagnosis and possibly identifying the culprit species. Pars plana vitrectomy may be considered a reasonable primary modality to remove larvae in the vitreous, to prevent an ocular inflammatory reaction.

Patient consent

Consent to publish the case report was not obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Funding

This report is supported by an unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY; and Core grant P30 EY010572 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD).

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Conflict of interest

The following authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures: HHC, RKS, JB, DJW, AKL.

Acknowledgements

No other acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Homer H. Chiang, Email: Homer.Chiang@med.uvm.edu.

Rasanamar K. Sandhu, Email: rasnasandhu@gmail.com.

Justin Baynham, Email: justin.baynham@gmail.com.

David J. Wilson, Email: wilsonda@ohsu.edu.

Andreas K. Lauer, Email: lauera@ohsu.edu.

References

- 1.Custis P.H., Pakalnis V.A., Klintworth G.K. Posterior interna ophthalmomyiasis; identification of a surgically removed Cuterebra larva by scanning electron microscopy. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon J.M., Winkler C.H., Nelson J.H. Ophthalmomyiasis interna caused by Cuterebra larva. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1969;67:110–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien C.S., Allen J.H. Ophthalmomyiasis interna anterior: report of Hypoderma larva in anterior chamber. Am J Ophthalmol. 1939;22:996–998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagacé-Wiens P.R., Dookeran R., Skinner S. Human ophthalmomyiasis interna caused by Hypoderma tarandi. North Can Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:64–66. doi: 10.3201/eid1401.070163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearney M.S., Nilssen A.C., Lyslo A. Ophthalmomyiasis caused by the reindeer warble fly larva. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:276–284. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.4.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron J.A., Shoukrey N.M., Al-Garni A.A. Conjunctival ophthalmomyiasiss by the sheep nasal botfly (Oestrus ovis) Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:331–334. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76736-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kersten R.C., Shoukrey N.M., Tabbara K.F. Orbital myiasis. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1228–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savino D.F., Margo E., McCoy E.D. Dermal myiasis of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1225–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Özyol P., Özyol E., Sankur F. External ophthalmomyiasis: a case series and review of ophthalmomyiasis in Turkey. Int Ophthalmol. 2016 Dec;36(6):887–891. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0204-9. PubMed PMID: 26895273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanifar A.A., Espiritu M.J., Myung J.S. Three-dimensional spectral domain optical coherence tomography and light microscopy of an intravitreal parasite. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015 Dec;5:33. doi: 10.1186/s12348-015-0064-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodger D.C., Kim E.L., Rao N.A. Ophthalmomyiasis interna. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:247. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogt R., Holzmann T., Jägle H. Ophthalmomyiasis externa. Ophthalmologe. 2015;112:61–63. doi: 10.1007/s00347-014-3087-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akçakaya A.A., Sargın F., Aslan Z.İ., Sevimli N., Sadigov F. External ophthalmomyiasis seen in a patient from Istanbul, Turkey. Turk Parazitol Derg. 2014;38:205–207. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2014.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arslan F., Mete B., Oztürk R. External ophthalmomyiasis caused by Oestrus ovis in İstanbul. Trop Doct. 2010;40:186–187. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.090464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pather S., Botha L.M., Hale M.J., Jena-Stuart S. Ophthalmomyiasis externa: case report of the clinicopathologic features. Int J Ophthalmic Pathol. 2013;2:2324–2329. doi: 10.4172/2324-8599.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi W., Kim G.E., Park S.H., Shin S.E., Park J.H., Yoon K.C. First report of external ophthalmomyiasis caused by Lucilia sericata Meigen in a healthy patient without predisposing risk factors. Parasitol Int. 2015 Oct;64:281–283. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gass J.D.M., Lewis R.A. Subretinal tracks in ophthalmomyiasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:1500–1505. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910040334008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulus Y.M., Butler N.J. Spectral-Domain optical coherence tomography, wide-field photography, and fundus autofluorescence correlation of posterior ophthalmomyiasis interna. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retin. 2016;47:682–685. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160707-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziemianski M.C., Ky Lee, Sabates F.N. Ophthalmomyiasis interna. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:1588–1589. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040440008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Syrdalen P., Stenkula S. Ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225:103–106. doi: 10.1007/BF02160340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gözüm N., Kir N., Ovali T. Internal ophthalmomyiasis presenting as endophthalmitis associated with an intraocular foreign body. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34:472–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards K.M., Meredith T.A., Hagler W.S., Healy G.R. Ophthalmomyiasis interna causing visual loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;97:605–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syrdalen P., Nitter T., Mehl R. Ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior: report of case caused by the reindeer warble fly larva and review of previous reported cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:589–593. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.9.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankar M.K., Diddapur S.K., Nadagir S.D. Ophthalmomyiasis externa caused by Oestrus ovis. J Lab Physicians. 2012;4:43–44. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.98671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakusin W. Ocular myiasis interna caused by the sheep nasal bot fly (Oestrus ovis L.) S Afr Med J. 1970;10:1155–1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taba K.E., Vanchiere J.A., Kavanaugh A.S., Lusk J.D., Smith M.B. Successful treatment of ophthalmomyiasis interna posterior with ivermectin. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6:91–94. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e318208859c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakamatsu T.H., Pierre-Filho P.T. Ophthalmomyiasis externa caused by Dermatobia hominis: a successful treatment with oral ivermectin. Eye. 2006;20:1088–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]