SUMMARY

The lysosomal membrane is the locus for sensing cellular nutrient levels, which are transduced to mTORC1 via the Rag GTPases and the Ragulator complex. The crystal structure of the five-subunit human Ragulator at 1.4 Å resolution was determined. Lamtor1 wraps around the other four subunits to stabilize the assembly. The Lamtor2:Lamtor3 dimer stacks upon Lamtor4:Lamtor5 to create a platform for Rag binding. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange was used to map the Rag binding site to the outer face of the Lamtor2:Lamtor3 dimer and to the N-terminal intrinsically disordered region of Lamtor1. EM was used to reconstruct the assembly of the full-length RagAGTP:RagCGDP dimer bound to Ragulator at 16 Å resolution, revealing that the G-domains of the Rags project away from the Ragulator core. The combined structural model shows how Ragulator functions as a platform for the presentation of active Rags for mTORC1 recruitment, and might suggest an unconventional mechanism for Rag GEF activity.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1) is a master growth regulator implicated in human diseases ranging from cancer to type-2 diabetes to neurodegeneration. In response to the combined action of nutrient, growth factor and energy inputs, mTORC1 drives mass accumulation, an obligate prerequisite for cell division, by upregulating multiple anabolic programs including protein, lipid and nucleotide synthesis, while suppressing catabolic programs such as autophagy and lipid catabolism (Perera and Zoncu, 2016; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017).

A key step in mTORC1 activation is its nutrient-driven recruitment to the surface of lysosomes, where the kinase activity of mTORC1 is unlocked. In mammalian cells amino acids, along with glucose and cholesterol, trigger the lysosomal translocation of mTORC1 via a mechanism that requires the Ras-related, heterodimeric Rag guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) and the pentameric Ragulator complex (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Castellano et al., 2017; Efeyan et al., 2013; Sancak et al., 2010; Sancak et al., 2008). The Rag GTPases, composed of RagA or RagB (which are functionally equivalent to each other) in complex with RagC or RagD (also functionally equivalent), are thought to directly bind to the Raptor subunit of mTORC1, anchoring it to the lysosomal membrane (Kim et al., 2008; Sancak et al., 2010; Sancak et al., 2008). Binding to Raptor requires RagA/B to be GTP-loaded, while RagC/D must be GDP-loaded. Nutrients are thought to induce the RagA/BGTP-RagC/DGDP active state via a series of dedicated sensors that, in turn, control GTPase Activating Proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) specific for either Rag component (Bar-Peled et al., 2012; Barad et al., 2015; Chantranupong et al., 2016; Saxton et al., 2016; Wolfson et al., 2016; Zoncu et al., 2011). For example, the Gator1 complex has been shown to function as a GAP that promotes GTP hydrolysis by RagA/B, thus causing mTORC1 detachment from the lysosome when nutrient levels are low (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Panchaud et al., 2013). Conversely, in high nutrients the RagC/D-specific GAP, Folliculin (FLCN)-FNIP, promotes switching of the Rag heterodimer to the mTORC1-binding configuration (Peli-Gulli et al., 2015; Petit et al., 2013; Tsun et al., 2013).

Unlike other Ras-superfamily GTPases, the Rags lack any lipidation motifs and thus cannot directly bind to the lysosomal lipid bilayer. The Ragulator/Lamtor complex, composed of the p18, p14, MP1, c7orf59 and HBXIP (also known as Lamtor1-5, respectively, and referred to hereafter as such) provides an essential Rag-anchoring function via myristoylation and palmiotoylation of the p18 subunit (Bar-Peled et al., 2012; Nada et al., 2009; Sancak et al., 2010; Teis et al., 2002). The membrane anchoring function of Ragulator is underscored by the observation that, when any of its subunits is deleted, both the Rag GTPases and mTORC1 become constitutively inactivated in the cytoplasm (Sancak et al., 2010).

Despite clear genetic and biochemical evidence that Ragulator and Rag GTPases form a two-tiered scaffolding complex for mTORC1, a structural understanding of the overall organization of the Ragulator-Rag assembly, and of the critical interfaces that mediate their interaction, is lacking. Thus, our understanding of how mTORC1 is captured to the lysosomal surface remains severely limited.

Most of the current structural understanding of Rag GTPase and Ragulator come from studies in yeast. This organism possesses one RagA/B ortholog, Gtr1, and one RagC/D ortholog, Gtr2. Similar to the mammalian Rags, Gtr1 and Gtr2 localize to the vacuolar surface, dimerize with each other and must be in the Gtr1GTP-Gtr2GDP state in order to activate TORC1 (Binda et al., 2009; Nicastro et al., 2017). The 2.8 Å crystal structure of the Gtr1-Gtr2 heterodimer, loaded with non-hydrolyzable GMP-PNP, revealed a pseudo two-fold symmetry in which the two GTPase domains face away from each other and do not directly interact. Dimerization of the two Rag components is provided by the C-terminal domains (CTDs), which have a roadblock fold consisting of a central five-stranded β-sheet flanked by one α-helix on the G-domain side and two α-helices on the other (Gong et al., 2011). Comparison of the Gtr1GMPPNP-Gtr2GMPPNP structure with a Gtr1GMPPNP-Gtr2GDP one suggests that, upon GTP hydrolysis, the Gtr2 G-domain undergoes a 28° rotation relative to its CTD. This movement expands a common surface, contributed by the Gtr1 and Gtr2 G-domains, which may enable binding to the Raptor/Kog1 subunit of TORC1 (Gong et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2012).

Yeast also has a vacuole-associated Ego ternary complex (Ego-TC) that is thought to perform an equivalent function to mammalian Ragulator in anchoring the Gtrs to the vacuolar surface (Nicastro et al., 2017; Powis et al., 2015). Within this complex, Ego1 is the lipidated subunit; Ego2 has a type-I roadblock fold highly similar to that of Lamtor 4 and 5, whereas Ego3 has a type-II roadblock fold highly similar to that of Lamtor 2 and 3, and distinguished from type-I by the presence of an additional alpha helix. The crystal structure of the Lamtor2/3 subcomplex is highly similar to the Ego3 homodimer, and revealed a near-symmetrical protein platform onto which additional interactions can be built (Kurzbauer et al., 2004; Powis et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012). However, how the Lamtor2-3 and Lamtor 4-5 dimers are brought together, and whether p18/Lamtor1 contributes to their overall stabilization is unclear.

It has been proposed that the Rag GTPases interact with Ragulator via binding of their roadblock-folded CTDs to 2 or more Ragulator subunits. However, the exact subunit composition of the Ragulator-Rag binding interface remains unknown. It is also unclear whether this interface is inherently static or whether factors such as nucleotides, post-translational modifications or interacting proteins can affect its stability in order to modulate the amount of mTORC1 that can access the lysosomal surface.

In addition to its Rag-scaffolding role, Ragulator has been proposed to function as a GEF that promotes GTP loading of RagA/B and thus contributes to switching the Rags to the active state under high nutrients (Bar-Peled et al., 2012). The GEF function of Ragulator seems to be specific to RagA/B, requires all five subunits, and may be triggered by amino acids signaling through lysosomal membrane proteins, SLC38A9 and vacuolar H+ ATPase (v-ATPase) (Wang et al., 2015; Zoncu et al., 2011). Due to the lack of a structural view of the entire Ragulator-Rag GTPase complex, it is unclear which subunits of Ragulator participate in the GEF activity and whether the involved mechanism bears resemblance to how other Ras superfamily GTPases interact with their respective exchange factors. Moreover, whether the scaffolding and GEF activities of Ragulator are separable or intrinsically linked is unknown.

Crystallization of the entire Ragulator-Rag GTPase assembly has so far proven elusive. To shed light into its overall organization and regulatory functions, we obtained an atomic resolution (1.43 Å) crystal structure of Ragulator, and fitted it within a low resolution (16.2 Å) electron microscopy (EM) map of the Ragulator-Rag supercomplex. Combining homology modeling and protein mapping methods, we obtain a model that reveals stacking of the two Rag CTDs onto Lamtor2/3 as the primary interacting surface, and suggests how this interface can be dynamically regulated by the nucleotide state of RagA/B in order to control the efficiency of lysosomal mTORC1 capture. Moreover we find that, unlike classical Ras GEFs, the ordered core Ragulator does not directly contact the Rag G-domains. Instead, the N-terminal intrinsically disordered region (IDR) of Lamtor1 appears to engage with the Rag dimer in an unusual variation on GEF mechanism.

Results

Mapping and expression of the Ragulator core

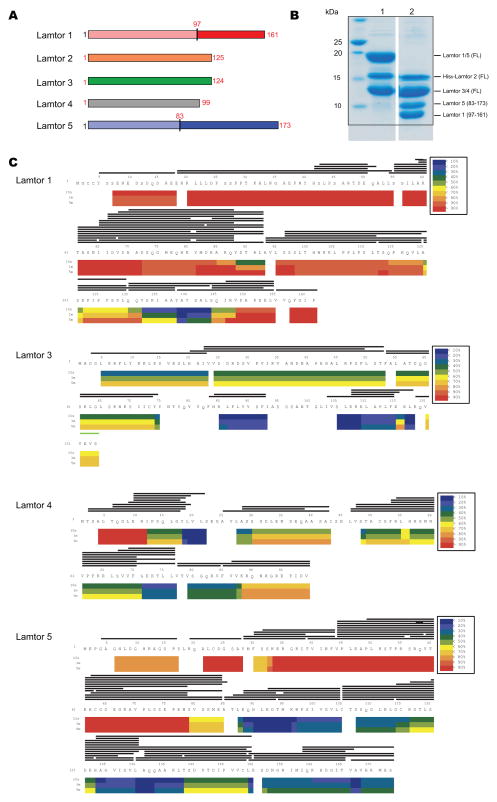

Full-length human Ragulator subunits Lamtor1-5 (Fig. 1A) were co-expressed in insect cells and purified (Fig. 1B). In order to differentiate folded and IDR regions of the subunits, the complex was subjected to hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) (Chalmers et al., 2011; Engen, 2009; Englander, 2006) for 10s, 1 min, and 5 min. Excellent peptide coverage was obtained with the sole exception of Lamtor2 (Fig. 1C), and consistent patterns were seen at all three time points. Lamtor3 and 4 are essentially roadblock domain-only subunits (Fig. 1A). Lamtor3 was well-protected throughout, and Lamtor4 protected except for the first 12 amino acids (Fig. 1C). Most of the N-terminal 80 amino acids of Lamtor5 exchanged rapidly, consistent with intrinsic disorder, while the C-terminal roadblock domain was well-protected (Fig. 1C). These observations are consistent with the boundaries of the previously crystallized portions of Lamtor3 and 5 (Garcia-Saez et al., 2011; Kurzbauer et al., 2004). Lamtor1 is the only non-roadblock subunit of Ragulator (Fig. 1A). The N-terminal ~100 and C-terminal ~15 amino acid residues of Lamtor1 exchanged quickly, with residues 100–150 protected to varying degrees. Residues 123–149 were the most protected (Fig. 1C); these largely correspond to residues of yeast Ego1 that were ordered in the previously crystallized Ego1-2-3 complex (Powis et al., 2015). Thus these data are in accord with the pre-existing structural data where available, as well as internally consistent across various time points. We placed high confidence in these results, and used them to design Lamtor1 and 5 truncation constructs for the crystallization of the ordered core of Ragulator.

Figure 1. Domain structure and dynamics of Ragulator.

(A) Schematic diagram of the domain structures of Ragulator (Lamtor1-5). The roadblock domains are labeled. The boundaries of the constructs we used for crystallization are highlighted in red. (B) The purified full length and truncated Ragulator were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1: Full-length Ragulator; Lane 2: truncated Ragulator for crystallization. (C) Deuterium uptake data for full-length Ragulator (Lamtor1-5). HDX- MS data are shown in heat map format where peptides are represented using rectangular strips above the protein sequence. Absolute deuterium uptake after 10s, 1m and 5m is indicated by a color gradient below the protein sequence.

Crystal Structure of Ragulator

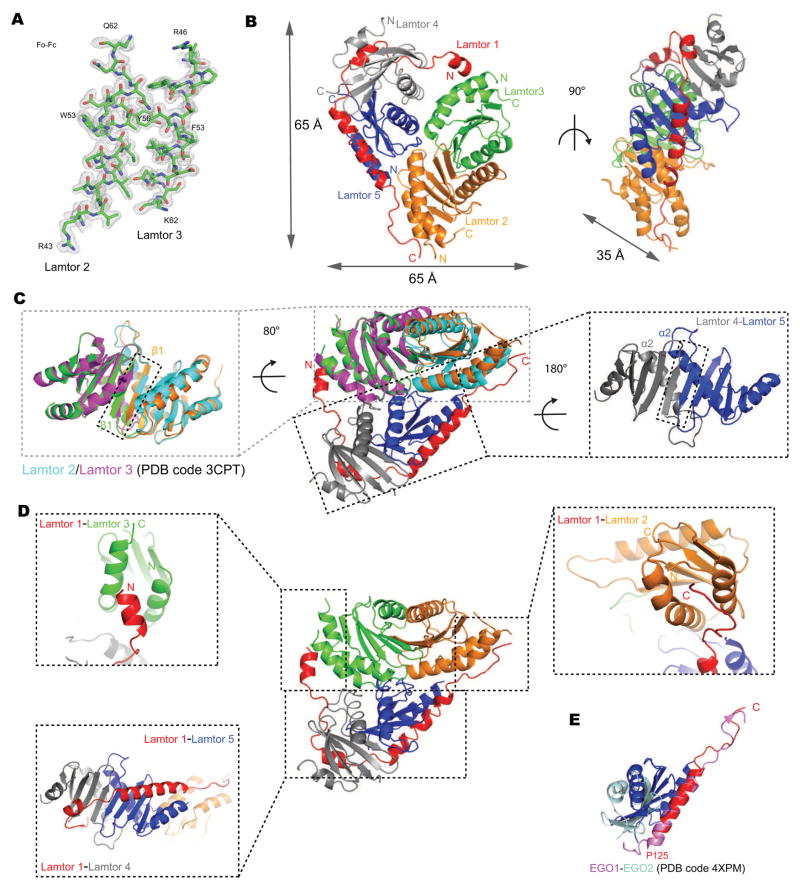

The structure of the ordered core of Ragulator was determined at 1.43 Å resolution by molecular replacement with the previously solved substructures (Fig. 2A, Fig. S1–2, Table 1). The structure is roughly a V-shaped slab with 65 Å-long edges and 35 Å thick (Fig. 2B). The structure consists of the roadblock domain heterodimers of Lamtor4-Lamtor5 and Lamtor2-Lamtor3, which are stacked upon each other at an angle in head-to-tail fashion, and cradled within the enveloping arch of Lamtor1. The Lamtor2-Lamtor3 dimer assembles via antiparallel contacts between helices α2 from both subunits and the formation of a continuous β-sheet through both subunits via antiparallel hydrogen-bonding between the two β1 strands (Fig. 2C), as seen in the isolated Lamtor2-Lamtor3 structure (Kurzbauer et al., 2004) (Fig. 2C). The Lamtor4-Lamtor5 dimer is similarly held together by antiparallel α2 helical contacts and a shared β-sheet (Fig. 2C). The roadblock domain dimer interfaces are extensive, consisting of 1281 and 1006 Å2, respectively.

Figure 2. Crystal structure of Ragulator.

(A) The omit map corresponding to the Lamtor2 (A42-Q62) and Lamtor3 (R46-K62) displayed at a contour level of 2σ (gray). (B) The overall structure of the truncated Ragulator shown in a ribbon representation colored as Fig1A. (C) Superposition of the Lamtor2-3 structure reported previously (PDB code 3CPT, in magenta and cyan) and the Lamtor2-3 structure from this study in the complex of Ragulator (left). Lamtor 4-5 dimer interface was shown on the right. (D) The contact between Lamtor1 with other subunits within Ragulator. (E) Structure-based alignment of Lamtor1-5 with yeast EGO1-2 (colored in pink and lightblue respectively, PDB code 4XPM).

Table 1.

Statistics of Crystallographic Data Processing and Refinement

| Ragulator | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P 61 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 168.71, 168.71, 52.325 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.12 |

| Resolution (Å) | 146.1-1.43 |

| No. of reflections | 139258 |

| Completeness (%) | 93.6 (94.4) |

| Redundancy | 9.1 (7.7) |

| Rsym | 0.07 (1.94) |

| <I>/<σ(I)> | 12.12 (0.7) |

| CC1/2 | 0.99 (0.33) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 146.1 - 1.50 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 0.1918/0.2121 |

| Average B-factor | 35.23 |

| R.m.s. deviation from ideality | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.006 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.931 |

| Ramachandran Plot (%) | |

| Favored | 98.2 |

| Allowed | 1.6 |

| Outliers | 0.2 |

Lamtor1 has a unique role in the complex as the only non-roadblock domain subunit. Lamtor1 contains three α-helices, but has no hydrophobic core of its own. Its helices α1, α2, and α3, and its extended regions are splayed out across the outer surfaces of all four of the other subunits. From N- to C-, Lamtor1 contacts Lamtor3, 4, 5, and 2, in turn. Contacts occur between Lamtor1-α1 and Lamtor3-α1 and α3; Lamtor1-α2 with Lamtor4-α1 and the outer face of the Lamtor4 β-sheet; Lamtor1-α3 with Lamtor5-α1 and β-sheet face; and the extended C-terminus of Lamtor1 with Lamtor2-α1 and α3. The Lamtor1 binding sites of Lamtor2 and Lamtor3 are quasi-equivalent to one another, both being formed between the N- and C-terminal helices of the roadblock unit (Fig. 2D). The Lamtor1 binding sites on Lamtor4 and Lamtor5 are also quasi-equivalent to each other, in this case, formed between the N-terminal helix and the face of the β-sheet (Fig. 2D). The structure suggests that Lamtor1- α2 and Lamtor1- α3 essentially complete Lamtor4 and Lamtor5, respectively, turning them into type II roadblock domains like Lamtor2 and Lamtor3. The latter interfaces provide more scope for a broad binding surface, thus the interfacial area is nearly twice as large as the interface with Lamtor2-Lamtor3. The Lamtor1 contacts bury 950 Å2 and 1892 Å2, respectively, in interfaces with the Lamtor2-Lamtor3 and Lamtor4-Lamtor5 dimers. The large amount of buried surface area seems undoubtedly critical to the folding of Lamtor1 and to the stability of the overall complex.

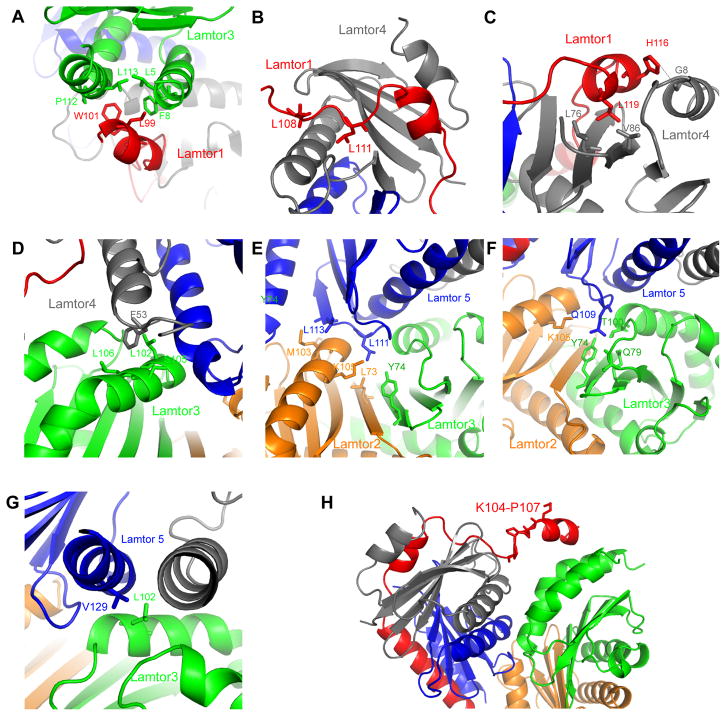

The longest helix of Lamtor1, α3, packs against Lamtor5 and consists of residues 125–146, corresponding generally to the geometry of the yeast Ego1-2 subcomplex (Powis et al., 2015) (Fig. 2E). This region also agrees closely with its most protected region in the HDX experiments. In contrast, the interactions of Lamtor1 with Lamtor3/4 have no counterpart in the yeast Ego1-2-3 crystal structure. Lamtor1 Leu99 and Trp102 anchor Lamtor1 α1 to the groove between Lamtor3 α1 and α3. Lamtor3 contributes Leu5, Phe8, Pro112, and Leu113 to this site (Fig. 3A). Lamtor1 makes a more complex set of interactions with Lamtor4. The more N-terminal portion of the Lamtor4-binding site on Lamtor1 has an extended conformation, and contacts first Lamtor4 α2, before wedging itself into the gap where Lamtor4 strands β3 and β4 splay apart. Lamtor1 Leu108 and Leu111 are the major anchors for this section (Fig. 3B). Lamtor1 α2, and a few C-terminal residues thereafter, then bind to the outer face of the Lamtor4 β-sheet. Here, Lamtor1 Leu119 is the major hydrophobic anchor, whilst His116 hydrogen bonds with a main-chain carbonyl from Lamtor4 α1 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Subunit interfaces of Ragulator.

(A) Key residues on the interface between Lamtor 1-Lamtor 3. (B) Key residues on the interface between Lamtor1-Lamtor 4. (C) Detail of the hydrophobic core and hydrogen bond between Lamtor1-Lamtor 4. (D) Interaction between Lamtor 3-Lamtor4, mainly mediated by F53 of Lamtor4. (E) Hydrophobic interaction between Lamtor2-Lamtor3-Lamtor5. (F) Hydrogen bonding between Lamtor2-Lamtor3-Lamtor5. (G) Hydrophobic interaction between Lamtor3-Lamtor5. (H) Loose interface between Lamtor3-Lamtor4, anchored by Lamtor1 K104-P107.

The interface between the two roadblock dimers involves 1206 Å2. Most of this interface is contributed by the binding of Lamtor5 with both subunits of the Lamtor2-Lamtor3 dimer. In contrast, Lamtor4 makes limited interactions with the Lamtor3, mainly via Phe53 of Lamtor4 α2 (Fig. 3D), and Lamtor4 has no direct contact with Lamtor2. Lamtor5 inserts a wedge formed by roadblock strands β1 and β2, and the β1-β2 turn, into the crevice between the α3 helices of Lamtor2/3. Lamtor5 β2 makes prominent hydrophobic contacts via its Leu111 and Leu113 side chains (Fig. 3E). Lamtor5 Gln109 projects from the β1-β2 turn and participates in a hydrogen bonding network with the side chains of Lamtor2 Lys105 and Lamtor3 Tyr74, Gln79, and Thr100, and the main-chain of Lamtor3 Ser96, which is part of a 310 helical turn (Fig. 3F). Lamtor5 α2 also makes a number of contacts with Lamtor3 α3, centered on the hydrophobic interaction between Lamtor3 Leu102 and Lamtor5 Val129 (Fig. 3G). Overall, the complex is tightly held together from within by the nexus of Lamtor5 at the tip of the V, and from without by the encirclement of all of the other subunits by Lamtor1. In contrast, the relative lack of interactions between Lamtor3 and 4 at the open end of the V, and the loosely anchored Lamtor1 connector region Lys104-Pro107 across the gap (Fig. 3H), appear to leave room for some overall subunit motions in the structure.

RagA/C binding sites of Ragulator

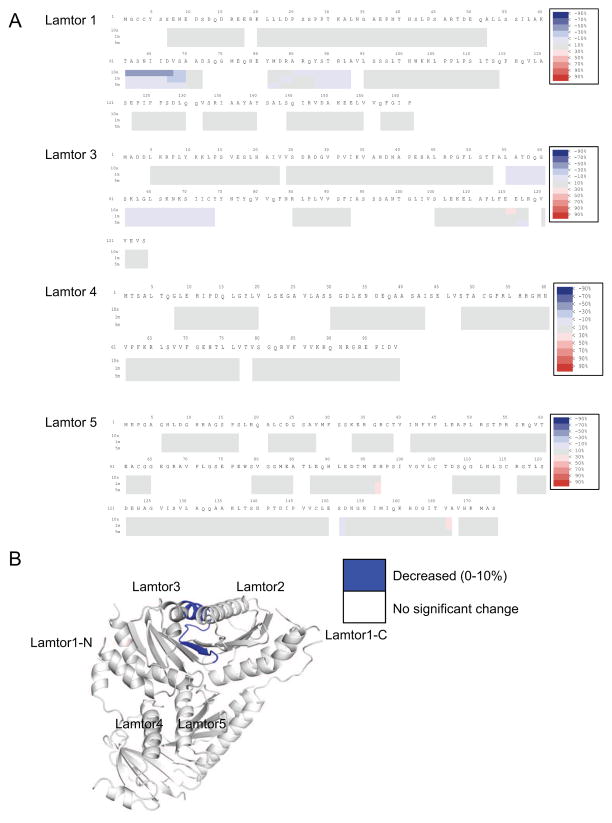

In order to map the location of the RagA/C binding sites on Ragulator, we purified the active Rag dimer RagAQ66L-GTP and RagCD181N-XDP. HDX-MS data were collected for three time points in the presence of active RagA/C dimer and compared to spectra for Ragulator obtained in its absence. The difference heat maps for Lamtor1 and 3–5 are shown in Fig. 4A, with inadequate peptide coverage limiting analysis of Lamtor2. Moderate protection of up to 10% was observed for Lamtor3 residues 55–74, corresponding to the α2-β3 region. This region is involved in heterodimerization with Lamtor2 and forms part of a broad, solvent-exposed surface (Fig. 4B). We concluded that this surface of the Ragulator core binds to RagA/C. The greatest increase in protection, a remarkable and highly significant 50% at the 10 s time point, was observed for residues 61–70 of the N-terminal IDR of Lamtor1. Despite their disorder in the context of the Ragulator structure, this region is one of the most highly conserved in Lamtor1, with a number of residues identically conserved even in yeast Ego1 (Fig. S1). From this result, we conclude that the sequence 61-TASNIIDVSA-70 of Lamtor1 is centrally involved in binding to RagA/C. The first ordered residue of Lamtor1 in the Ragulator core structure is Ser97. This leads to the striking and unexpected conclusion that Ragulator binds RagA/C in a bipartite manner, combining interactions with both the Lamtor2/3 face of the ordered core and with a part of the Lamtor1 IDR that is separated from the core by a gap of 26 amino acids.

Figure 4. HDX-MS of Ragulator in the presence of RagA/C.

(A) Each block indicates peptide analyzed with three time points. From the top, 10s, 1m and 5m. The difference heat map of relative deuteration levels between apo and bound states is indicated by difference colors, as indicated at upper right. (B) HDX results from part (A) were mapped onto the crystal structure, with the N-terminus of Lamtor1 omitted because of its disorder in the crystal structure. Note that there is no MS coverage for Lamtor2.

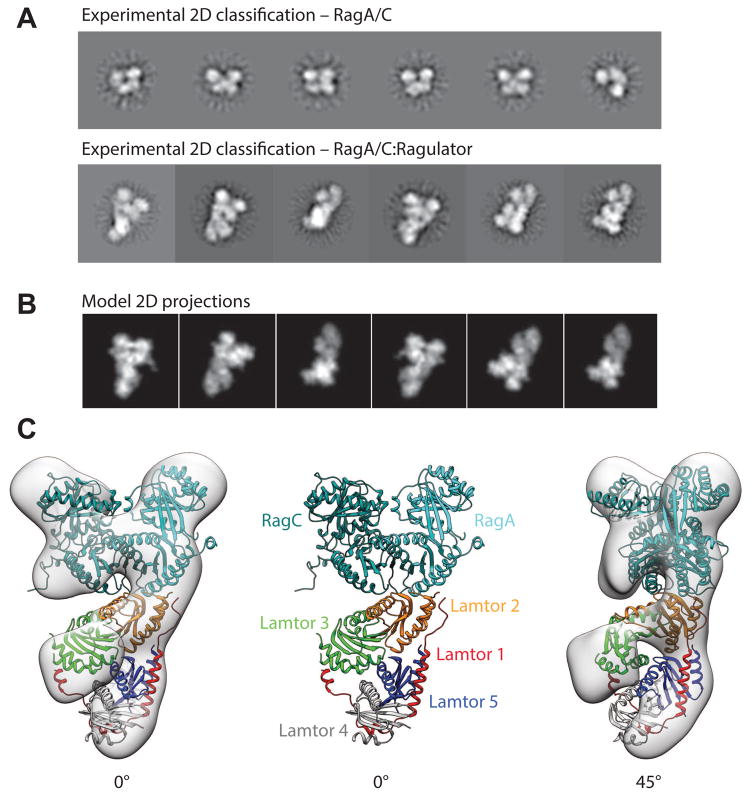

Electron microscopy of the Ragulator-RagAC complex

The structure of the RagA/C (RagAQ66L-GTP:RagCD181N-XDP):Ragulator complex was determined by negative stain EM (Fig. 5A,B, Fig. S3). The structure converged on a resolution of 16.2 Å, allowing us to model the domain structure of the whole complex based using the yeast Gtr1GMPPNP-Gtr2GDP structure (Jeong et al., 2012) to model the RagA/C dimer, and our Ragulator crystal structure as starting points. The complex consists of a bi-lobed head structure with a platform supporting these (Fig 5C). The density is consistent with the double-headed architecture of the heterodimeric RagA/C structure on the basis of its homology to Gtr1-2 (Gong et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2012). The EM analysis is limited by the available resolution. At 16 Å, RagA and RagC appear essentially identical, and the assignment of RagA to one side and RagC to the other was ambiguous. On the basis of the report by de Araujo (2017), the assignment shown in Fig. 5C was selected. In our structure, the Lamtor2/3 face of Ragulator is associated with the RagA/C density via the roadblock domains of RagA/C. RagA/C interactions are principally with the Lamtor2 side of the Lamtor2/3 face, although the docked model also predicts that side-chains of Lamtor3 α2 are close to those of the C-terminal helix of RagC. The EM density is clear and the fit of Ragulator and RagA/C to the density is unambiguous. Moreover, the interaction observed with the Lamtor2/3 face is consistent with the HDX-MS data. The central and surprising observation from the EM is that core of Ragulator makes no direct contacts to the G-domains of RagA/C.

Figure 5. The structure of full-length RagA/C:Ragulator by electron microscopy.

(A) Representative 2D class averages of RagA/C dimer in comparison to whole RagA/C:Ragulator complex (B) Calculated 2D projections from the modelled complex show good agreement to the experimentally observed views supporting the modelled domain architecture as shown (C) fitted into the 3D reconstructed volume.

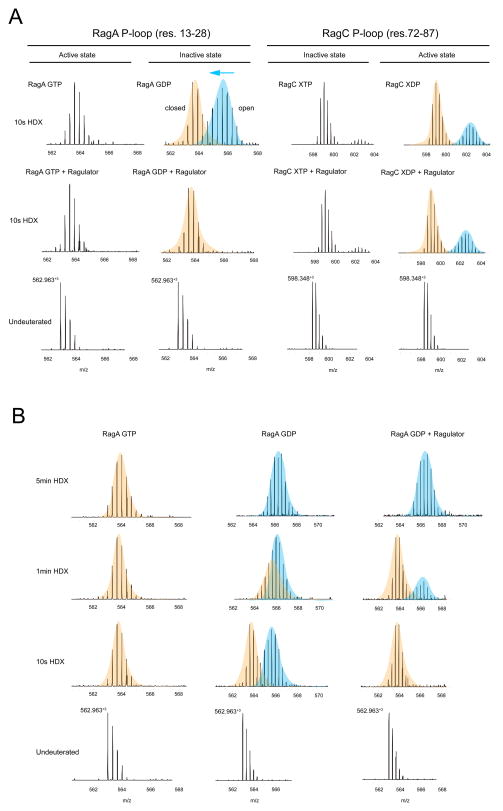

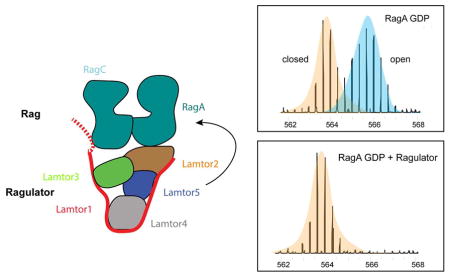

Inactive RagA G-domain dynamics are altered by Ragulator

Given the remarkable and unexpected finding that the ordered core of Ragulator has no direct interactions with the RagA/C G-domains, we sought to probe whether there was any physical evidence for a Ragulator effect on the structure or dynamics of the G-domains. We prepared both “active” RagAQ66L-GTP:RagCD181N-XDP and “inactive” RagAQ66L-GDP:RagCD181N-XTP dimers (Fig. S4) and obtained HDX-MS data in the presence and absence of Ragulator with excellent coverage (Fig. S5). We monitored the dynamics of the RagA and C P-loop peptides, residues 13–28 and 72–87, respectively. RagA in the GTP state shows a single slowly exchanging molecular mass envelope in the presence or absence of Ragulator (Fig. 6A). However, in the GDP state and in the absence of Ragulator, the P-loop of RagA manifests two mass envelopes (Fig. 6A). The second envelope corresponds to a more rapidly exchanging conformation which is uniquely associated with the GDP state. Upon addition of Ragulator, this conformation is completely suppressed. Thus, Ragulator depopulates the unique GDP-dependent fast-exchanging state of the RagA P-loop, consistent with its proposed function as a GEF for RagA. This behavior is evident at 10 s to 1 min of exchange. By 5 min, the RagA 13–28 peptide has fully exchanged in all conditions (Fig. 6B). Like RagA, RagC manifests a single slowly exchanging envelope in the GTP state. There is evidence for a trace population of a faster exchanging conformation, which is likely due to presence of trace amounts of XDP. In the GDP (XDP) state, a larger proportion of a rapidly exchanging envelope appears. In contrast to the situation with RagA, the presence of Ragulator has no effect on this peak. These data are consistent with a direct physical effect of Ragulator on the dynamics of the RagA G-domain.

Figure 6. Ragulator modulates the dynamics of the RagA nucleotide binding site.

(A) Mass spectra for the peptides from the P-loop of RagA and RagC under active and inactive states in apo and bound state with Ragulator. (B) Mass spectra of the peptides from P-loop from RagA under active or inactive state in complex with Ragulator. Time points are indicated.

Discussion

Here, we have visualized the completely assembled architecture of the five-subunit human Ragulator complex, a pivotal regulator of mTORC1 translocation to the lyososomal membrane. Atomic details were obtained for Ragulator itself, while insights into its complex with the RagA/C dimer are to some extent limited by the resolution of the EM reconstruction. Some aspects of the architecture could have been inferred from fragmentary structures of yeast and human Ragulator. The roadblock heterodimer of Lamtor2/3 assembles much as previously observed (Kurzbauer et al., 2004), and the alignment of Lamtor1 with Lamtor2/5 could have been anticipated from the Ego1-2-3 complex (Powis et al., 2015). Lamtor4/5 heterodimerize, as expected on the basis of the Lamtor2/3 structure. On the other hand, the overall V-shape of the complex, with a loosely tethered opening between Lamtor3/4 was not anticipated. This is important as the space left in the middle of the V could provide scope for molecular movements during regulation by V-ATPase (Zoncu et al., 2011), SLC38A9 (Wang et al., 2015), or other factors. This structure revealed how the Lamtor2/3 and 4/5 roadblock dimers assemble with one another, which is key to the overall organization of the complex. The interactions of the two N-terminal helices with Lamtor2/4, and the remarkable overall encirclement of the roadblock subunits 2–5 by Lamtor1, were described.

Ragulator is reported to be a GEF for RagA (and B) (Bar-Peled et al., 2012), a property considered central to its ability to form the active RagAGTPRagCGDP dimer and so recruit and activate mTORC1. Yet HDX-MS and EM data both lead to the conclusion that the Ragulator core complex interacts directly only with the RagA/C roadblock dimer. There appears to be no direct contact between the Ragulator core and the G-domains of RagA/C. This lack of interaction between the GEF core scaffold and the G-domains is unusual. Numerous structures of small G-protein:GEF complexes have been determined, including those of EF-Tu:EF-Ts (Kawashima et al., 1996; Wang et al., 1997), Ras:Sos (Boriack-Sjodin et al., 1998), Arf1:Sec7 (Mossessova et al., 2003), Rab5:Rabex5 (Delprato and Lambright, 2007), and Ypt1:TRAPP (Cai et al., 2008). In every case, extensive interactions of an ordered GEF structural scaffold collaborate with invasion of the nucleotide-binding site to destabilize GDP binding. Having observed that Ragulator radically departs from this theme, we investigated further whether Ragulator could induce physical changes in RagA. We found by HDX-MS that Ragulator selectively destabilizes the GDP-specific conformation of RagA, consistent with the expectation for a functional RagA GEF. The mechanism whereby this conformational shift occurs remains to be elucidated.

The consensus function of the active RagA/C:Ragulator complex is to serve as a lysosomal recruitment platform for mTORC1, and our structure provides insights into how recruitment of mTORC1 by the RagA/C:Ragulator complex may occur. In particular, by sitting on the Lamtor 2-3 platform in an ‘upright’ position with its G domains facing the cytoplasm, the Rag heterodimer is ideally placed to capture mTORC1 molecules diffusing nearby. This upright, cytoplasm-facing configuration should be further aided by the intrinsically disordered, N-terminal lipidated region of Lamtor1, which further separates the Rags and the Ragulator ordered core from the lysosomal lipid bilayer. The overall footprint of the complex is ~135 × 65 Å, which provides abundant room for targeting the 290 × 210 × 135 Å mTORC1 structure (Aylett et al., 2016; Baretic et al., 2016; Yip et al., 2010). Among the notable features of the exposed surface of this complex, Lamtor2 Phe64 protrudes as a highly solvent-accessible finger, suggestive of a potential mTORC1 recruitment surface.

By pointing away from Ragulator, the Rag G-domains are also predicted to be highly accessible by their GAPs, Gator1 and FLCN (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Panchaud et al., 2013) (Peli-Gulli et al., 2015; Petit et al., 2013; Tsun et al., 2013). The recent identification of Kicstor as a lysosome-scaffolding complex for Gator1 that is essential for mTORC1 inhibition (Peng et al., 2017; Wolfson et al., 2017) suggests that GTP hydrolysis by RagA/B occurs at the lysosomal surface. Although no structural information is currently available on the Kicstor:Gator1 supercomplex, one would predict that the GAP core of Gator1 (likely provided by the Longin domains of Nprl2 and 3) is placed in an ideal orientation to make contact with the G-domain of RagA, so that their respective distances from the lysosomal membrane should match. In high amino acids, FLCN dissociates from the lysosomal surface, and likely accesses the RagC G-domain from the cytoplasmic side (Peli-Gulli et al., 2015; Petit et al., 2013; Tsun et al., 2013). Thus, FLCN-stimulated GTP hydrolysis could also be aided by the exposed configuration of the Rag G-domains.

While the initial version of this manuscript was under review, Scheffzek and colleagues reported the crystal structure of Ragulator alone and bound to the roadblock domains of RagA/C (de Araujo et al., 2017). The structure of Ragulator alone appears to be essentially the same as ours, reinforcing confidence in the accuracy of these structures. In the presence of the roadblock domains of RagA/C, Lamtor1 residues after 47 were found to be well-ordered (de Araujo et al., 2017), consistent with our observation of HDX protection for Lamtor1 residues 61–70 in the presence of RagA/C. Interacting residues, such as Lamtor1 Val148, mutated in this study reduce function, consistent with expectations from our structure. In spite of the limited resolution of the EM structure, the orientation deduced for the RagA/C dimer relative to Ragulator is very similar. Similar conclusions were drawn based on the two different approaches applied, EM reconstruction with a full-length active RagA/C dimer in this case, and crystallization with the RagA/C roadblock fragments in the other study (de Araujo et al., 2017). The structural insights presented in these two studies will set the stage for a more detailed analysis of into the critical question as to how the active Rag:Ragulator complex recruits and activates mTORC1, a central question at the heart of much current research into cellular metabolic regulation.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, James H. Hurley (jimhurley@berkeley.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All proteins used in experiments in this study were expressed in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells using ESF 921 Insect Cell Culture Medium, Protein Free (Expression Systems).

METHOD DETAILS

Cloning and protein purification

DNAs coding for full-length human Ragulator (Lamtor 1-5) and Rag GTPases (RagA and RagC) were subcloned into pFastBac Dual following the polyhedron and p10 promoters, respectively. For co-expression of Ragulator, three more copies of polyhedron promoters were constructed to the upstream of the genes. Lamtor 1 G2A was introduced for preventing the lipidation. For crystallization, Lamtor 1 (S97-P161) and Lamtor 5 (M83- S173) were co-expressed with full-length Lamtor 2-4. Full-length and truncated human Ragulator and Rag GTPases constructs (wild-type and RagAQ66L and RagCD181N) were co-expressed in Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells. Baculoviruses were generated in Sf9 cells with the bac-to-bac system (Life Technologies). Recombinant Lamtor1 was expressed with an N-terminal GST tag followed by a TEV protease cleavage site and Lamtor2 was His6 tagged and coexpressed with untagged Lamtor 3-5. Recombinant RagC was expressed in an N-terminal MBP-TEV tag with untagged RagA.

Cells were infected and harvested after 48 to 72 hours. Cells were pelleted at 2000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were lysed in 1X PBS pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM TCEP-HCl and protease inhibitors (Roche). GTP was included for purification of RagS. The lysate was centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 50 min at 4°C. The supernatant was bound to glutathione sepharose (GS4B) or amylose resin at 4 °C for 2 hrs and washed extensively with 1X PBS pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM TCEP and further applied to an on-column TEV digestion overnight. The flow-through was collected and concentrated for Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM TCEP-HCl. Peak fractions were collected and flash-frozen in liquid N2 for storage.

HDX-MS Experiments

Amide hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) was initiated by a 20-fold dilution of 15 μM Ragulator or RagS and RagS-Ragulator complex into D2O buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pD 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.5 mM TCEP at 30 °C. After intervals of 10s-5m, exchange was quenched at 0 °C with the addition of ice-cold quench buffer (400 mM KH2PO4/H3PO4, pH 2.2). Quenched samples were injected onto an HPLC (Agilent 1100) with in-line peptic digestion and desalting steps. Desalted peptides were eluted and directly analyzed by an Orbitrap Discovery mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Initial peptide identification was performed via tandem MS/MS experiments. A Proteome Discoverer 2.1 (Thermo Scientific) search was used for peptide identification. Mass analysis of the peptide centroids was performed using HDExaminer (Sierra Analytics, Modesto, CA), followed by manual verification of each peptide. The deuteron content was adjusted for deuteron gain/loss during digestion and HPLC.

Crystallization of Ragulator

Crystals of truncated Ragulator were obtained by mixing 1 μl of the protein concentrated to 5.36 mg/ml with an equal amount of reservoir solution consisting of 0.1 M CHES pH 9.0, PEG 600 using sitting-drop vapor diffusion at 19 °C. Crystals appeared in 1 day and grew to full size (0.30 × 0.10 × 0.15 mm) in a week. Crystals were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen in the well solution.

Data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data were collected at BL 8.3.1, Advanced Light Source (ALS), LBNL. The crystal giving the best X-ray diffraction to 1.42 Å collected at λ = 1.12 Å was used for data collection of a total of 5760 frames with 0.06 oscillation per frame. All data sets were processed with XDS. Data collection and processing statistics are given in Table 1. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007) using structures of Lamtor 2-Lamtor 3 (PDB code 1VET) (Kurzbauer et al., 2004) and Lamtor 5 (PDB code 3MS6) (Garcia-Saez et al., 2011) as the search models, followed by autobuilding using Buccaneer for chains of Lamtor 1 and Lamtor 4. Subsequently, the structure was manually rebuilt using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and refined using PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010). All protein model figures were generated with PyMOL (v.1.7; Schrödinger) (DeLano, 2002).

Negative stain EM of Rag-Ragulator complex

RagAQ66L and RagCD181N were loaded with GTP and XDP respectively. RagA/C was mixed with ragulator in equimolar amounts and incubated overnight at 4 °C, the reconstituted RagA/C:ragulator was purified using size exclusion chromotography on superdex S200 resin. A solution of RagA/C Ragulator was diluted into 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2 containing glutaraldehyde at 0.01% w/v and incubated at 4 °C for 15 minutes. The cross-linked solution of RagA/C Ragulator at 58 nM was incubated on glow discharged continuous carbon grids for 1 minute at room temperature. The sample solution was blotted with Whatman #1 filter paper and replaced with 2% Uranyl Formate to stain. Staining was performed twice with incubations of 1 minute. The protein complex was visualised at room temperature on a Tecnai F20 (FEI) operated at 120 keV and Gatan ultrascan camera. Micrographs were collected with a total dose of 35 e−/Å2, between a defocus of 1 – 3 μm and a magnified pixel size of 1.5 Å/pixel.

EM image processing

36,948 particles were picked in a template-free manner using gautomatch (K. Zhang, Cambridge) from 210 micrographs. 2D references were generated in Relion-2.0 (Kimanius et al., 2016; Scheres, 2012), and used for template based autopicking. 39,463 particles were extracted and 2D averaged into 100 classes. 2D classes were selected based on high population and visual inspection. Ab-initio classification and reconstruction was performed on these particles in Cryosparc (Punjani et al., 2017) producing a reference volume from 24,061 particles which were used for further refinement. Refinement in Cryosparc converged on a map with a determined resolution of 16.2 A (gold-standard FSC 0.143 criterion).

Molecular models were constructed in Coot. A trial molecular model was constructed based on the hypothesis that the RagA-RagC roadblock dimer would be related to the Lamtor2-Lamtor3 dimer by the same type of interface and transformation relating Lamtor2-Lamtor3 to Lamtor4-Lamtor5. The model was generated by homology to the structure of the yeast Gtr1-Gtr2 dimer (Gong et al., 2011; Jeong et al., 2012). For projection matching validation EMAN2 was used. The model was converted into a volume with a resolution of 1.5 Å/pixel and low pass filtered to 16 Å for comparison of model projections to experimental 2D averages. The model was fitted into the 3D density using UCSF Chimera fitmap. Essentially the same result was obtained as the top solution by using unbiased automated docking in Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package (Pettersen et al., 2004).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The atomic coordinates and structure factors for the Ragulator have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) under ID code 6B9X. The EM density map has been deposited in the EMDB under ID code EMD-7072.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Director’s New Innovator Award (1DP2CA195761-01), the Pew-Stewart Scholarship for Cancer Research, the Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovation Award and the Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. Foundation Grant to R.Z. Beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source, LBNL, is supported by the UC Office of the President, Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives grant MR-15-328599 and the Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, which is partially funded by the Sandler Foundation. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-Y. S., K. L. M., R. Z, and J. H. H.; Methodology, M.-Y. S., K. L. M., D.-J. K., Y. F., R. L., and G. S.; Investigation, M.-Y. S. and K. L. M.; Writing, M.-Y. S., K. L. M., R. Z. and J. H. H.; Validation, G. S.; Supervision, R. Z. and J. H. H.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr Sect D-Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylett CHS, Sauer E, Imseng S, Boehringer D, Hall MN, Ban N, Maier T. STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY Architecture of human mTOR complex 1. Science. 2016;351:48–52. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM. A Tumor Suppressor Complex with GAP Activity for the Rag GTPases That Signal Amino Acid Sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2013;340:1100–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1232044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator Is a GEF for the Rag GTPases that Signal Amino Acid Levels tomTORC1. Cell. 2012;150:1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barad BA, Echols N, Wang RYR, Cheng Y, DiMaio F, Adams PD, Fraser JS. EMRinger: side chain directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2015;12:943–946. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baretic D, Berndt A, Ohashi Y, Johnson CM, Williams RL. Tor forms a dimer through an N-terminal helical solenoid with a complex topology. Nature Communications. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda M, Peli-Gulli MP, Bonfils G, Panchaud N, Urban J, Sturgill TW, Loewith R, De Virgilio C. The Vam6 GEF controls TORC1 by activating the EGO complex. Mol Cell. 2009;35:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boriack-Sjodin PA, Margarit SM, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J. The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos. Nature. 1998;394:337–343. doi: 10.1038/28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Chin HF, Lazarova D, Menon S, Fu C, Cai H, Sclafani A, Rodgers DW, De La Cruz EM, Ferro-Novick S, et al. The structural basis for activation of the Rab Ypt1p by the TRAPP membrane-tethering complexes. Cell. 2008;133:1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano BM, Thelen AM, Moldavski O, Feltes M, van der Welle RE, Mydock-McGrane L, Jiang X, van Eijkeren RJ, Davis OB, Louie SM, et al. Lysosomal cholesterol activates mTORC1 via an SLC38A9-Niemann-Pick C1 signaling complex. Science. 2017;355:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.aag1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers MJ, Pascal BD, Willis S, Zhang J, Iturria SJ, Dodge JA, Griffin PR. Methods for the Analysis of High Precision DIfferential Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange Data. Int J Mass spectrom. 2011;302:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantranupong L, Scaria SM, Saxton RA, Gygi MP, Shen K, Wyant GA, Wang T, Harper JW, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM. The CASTOR Proteins Are Arginine Sensors for the mTORC1 Pathway. Cell. 2016;165:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo MEG, Naschberger A, Furnrohr BG, Stasyk T, Dunzendorfer-Matt T, Lechner S, Welti S, Kremser L, Shivalignaiah G, Offterdinger M, et al. Crystal structure of the human lysosomal mTORC1 scaffold complex and its impact on signaling. Science. 2017 doi: 10.1126/science.aao1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System DeLano Scientific. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Delprato A, Lambright DG. Structural basis for Rab GTPase activation by VPS9 domain exchange factors. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Chang S, Gumper I, Snitkin H, Wolfson RL, Kirak O, Sabatini DD, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 by the Rag GTPases is necessary for neonatal autophagy and survival. Nature. 2013;493:679–683. doi: 10.1038/nature11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr Sect D-Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engen JR. Analysis of Protein Conformation and Dynamics by Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange MS. Anal Chem. 2009;81:7870–7875. doi: 10.1021/ac901154s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry: A historical perspective. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Saez I, Lacroix FB, Blot D, Gabel F, Skoufias DA. Structural Characterization of HBXIP: The Protein That Interacts with the Anti-Apoptotic Protein Survivin and the Oncogenic Viral Protein HBx. J Mol Biol. 2011;405:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong R, Li L, Liu Y, Wang P, Yang H, Wang L, Cheng J, Guan KL, Xu Y. Crystal structure of the Gtr1p-Gtr2p complex reveals new insights into the amino acid-induced TORC1 activation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1668–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.16968011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JH, Lee KH, Kim YM, Kim DH, Oh BH, Kim YG. Crystal Structure of the Gtr1p(GTP)-Gtr2p(GDP) Protein Complex Reveals Large Structural Rearrangements Triggered by GTP-to-GDP Conversion. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29648–29653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.384420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T, BerthetColominas C, Wulff M, Cusack S, Leberman R. The structure of the Escherichia coli EF-Tu center dot EF-Ts complex at 2.5 angstrom resolution. Nature. 1996;379:511–518. doi: 10.1038/379511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:935–945. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SHW, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzbauer R, Teis D, de Araujo ME, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Hekman M, Rapp UR, Huber LA, et al. Crystal structure of the p14/MP1 scaffolding complex: how a twin couple attaches mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling to late endosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403435101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova E, Corpina RA, Goldberg J. Crystal structure of ARF1 center dot Sec7 complexed with brefeldin A and its implications for the guanine nucleotide exchange mechanism. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nada S, Hondo A, Kasai A, Koike M, Saito K, Uchiyama Y, Okada M. The novel lipid raft adaptor p18 controls endosome dynamics by anchoring the MEK-ERK pathway to late endosomes. EMBO J. 2009;28:477–489. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicastro R, Sardu A, Panchaud N, De Virgilio C. The Architecture of the Rag GTPase Signaling Network. Biomolecules. 2017;7 doi: 10.3390/biom7030048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchaud N, Peli-Gulli MP, De Virgilio C. Amino acid deprivation inhibits TORC1 through a GTPase-activating protein complex for the Rag family GTPase Gtr1. Science signaling. 2013;6:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peli-Gulli MP, Sardu A, Panchaud N, Raucci S, De Virgilio C. Amino Acids Stimulate TORC1 through Lst4-Lst7, a GTPase-Activating Protein Complex for the Rag Family GTPase Gtr2. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Yin N, Li MO. SZT2 dictates GATOR control of mTORC1 signalling. Nature. 2017;543:433–437. doi: 10.1038/nature21378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera RM, Zoncu R. The Lysosome as a Regulatory Hub. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2016;32:223–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit CS, Roczniak-Ferguson A, Ferguson SM. Recruitment of folliculin to lysosomes supports the amino acid-dependent activation of Rag GTPases. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:1107–1122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis K, Zhang T, Panchaud N, Wang R, De Virgilio C, Ding J. Crystal structure of the Ego1-Ego2-Ego3 complex and its role in promoting Rag GTPase-dependent TORC1 signaling. Cell Res. 2015;25:1043–1059. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag Complex Targets mTORC1 to the Lysosomal Surface and Is Necessary for Its Activation by Amino Acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Knockenhauer KE, Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Pacold ME, Wang T, Schwartz TU, Sabatini DM. Structural basis for leucine sensing by the Sestrin2-mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2016;351:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell. 2017;169:361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SHW. RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. Journal of Structural Biology. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teis D, Wunderlich W, Huber LA. Localization of the MP1-MAPK scaffold complex to endosomes is mediated by p14 and required for signal transduction. Dev Cell. 2002;3:803–814. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsun ZY, Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Zoncu R, Wang T, Kim C, Spooner E, Sabatini DM. The Folliculin Tumor Suppressor Is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases That Signal Amino Acid Levels to mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2013;52:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, et al. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2015;347:188–194. doi: 10.1126/science.1257132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Jiang YX, MeyeringVoss M, Sprinzl M, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of the EF-Tu center dot EF-Ts complex from Thermus thermophilus. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:650–656. doi: 10.1038/nsb0897-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Saxton RA, Shen K, Scaria SM, Cantor JR, Sabatini DM. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2016;351:43–48. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson RL, Chantranupong L, Wyant GA, Gu X, Orozco JM, Shen K, Condon KJ, Petri S, Kedir J, Scaria SM, et al. KICSTOR recruits GATOR1 to the lysosome and is necessary for nutrients to regulate mTORC1. Nature. 2017;543:438–442. doi: 10.1038/nature21423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip CK, Murata K, Walz T, Sabatini DM, Kang SA. Structure of the Human mTOR Complex I and Its Implications for Rapamycin Inhibition. Mol Cell. 2010;38:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Peli-Gulli MP, Yang H, De Virgilio C, Ding J. Ego3 functions as a homodimer to mediate the interaction between Gtr1-Gtr2 and Ego1 in the ego complex to activate TORC1. Structure. 2012;20:2151–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar H(+)-ATPase. Science. 2011;334:678–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.