Abstract

The demand for effective eye therapies is driving the development of injectable hydrogels as new medical devices for controlled delivery and filling purposes. This article introduces the properties of injectable hydrogels and summarizes their versatile application in the treatment of ophthalmic diseases, including age-related macular degeneration, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and intraocular cancers. A number of injectable hydrogels are approved by FDA as surgery sealants, tissue adhesives, and are now being investigated as a vitreous humor substitute. Research on hydrogels for drug, factor, nanoparticle, and stem cell delivery is still under pre-clinical investigation or in clinical trials. Although substantial progress has been achieved using injectable hydrogels, some challenging issues must still be overcome before they can be effectively used in medical practice.

Keywords: Injectable hydrogels, ophthalmology, drug delivery system, regenerative medicine

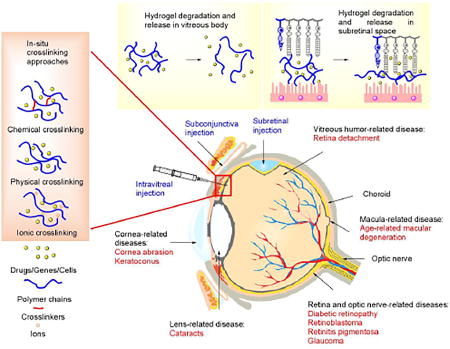

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

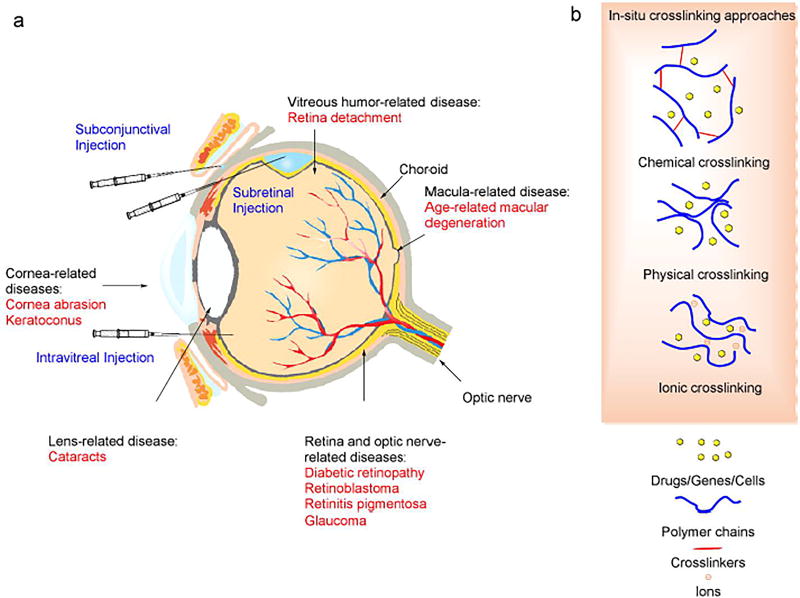

According to the statistics from the World Health Organization and other institutes, over 20 million patients were recorded as having ophthalmic diseases and disorders in the United States by 2014, and the total number of people with a visual impairment is estimated to be 285 million globally [1–6]. The prevalence of such diseases is forecast to double in 2050 based on demographic age [1, 2, 5, 6]. The human eye has a sophisticated multi-segmented structure, and malfunction of any segment may cause permanent vision loss or blindness. Eye segments are vulnerable to either inherited or contracted diseases and disorders (Figure 1), and the most commonly encountered diseases and disorders that cause visual impairment include cataracts, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, age-related diseases, inflammation, and intraocular tumors, as well as other diseases. These diagnoses lead to 26 million doctor visits annually in the US [1, 2, 7, 8] and more in other parts of the world.

Figure 1.

Anatomical structure of eye with related eye diseases or disorders and formation of in-situ gelation in an injectable hydrogel for ophthalmic diseases or disorders treatment.

To date, only a limited number of technologies have been available for ophthalmic disorders and disease therapy. Surgery-based techniques are used as the major therapies for damaged tissue and the delivery of therapeutic components (i.e., drugs, protein/peptides, genes, and nanoparticles) [9–11]. Surgical methods, however, are limited to therapies such as removal of the vitreous humor, refraction-correction, glaucoma treatment, and corneal transplant. Although therapeutic molecules have played a critical role in the therapy of congenital and acquired diseases, the challenge remains to improve the efficacy of drug delivery and minimize side effects and the off-target rate. Commonly used eye drops have little permeability to the cornea, and are thus limited to treatment in the outer segment of the eye. In conventional administration approaches such as topical eye drops, subconjunctival injection, and intravitreal injection, several physiologic and biologic barriers exist that the therapeutic payload must overcome (Figure 1). These include (1) tear film and lacrimation, (2) the corneal barrier, (3) the iris capillary endothelial barrier, (4) the epithelial barrier of ciliary body, (5) the retinal capillary barrier, and (6) the retinal pigment epithelial barrier [12, 13]. These approaches have the drawbacks of low efficiency, off-target delivery, side effects, and a short lifespan. Viral vectors, e.g. adeno-associated virus (AAV) and lentivirus, are highly effective transfection tools for gene therapy in ophthalmic research. However, this type of delivery vehicle has underlying safety concerns of immunogenicity, broad tissue tropism, carcinogenesis, and genomic insertional mutagenesis in clinical trials, thus in the end it is hoped that physicians and patients will accept only non-viral vectors as the standard of treatment [14].

The need for an effective delivery vehicle for a therapeutic payload is driving the development of materials on multiple scales. As a mimic of the extracellular matrix (ECM), hydrogels have the potential to serve as delivery vehicles for cells and drugs. This class of hydrophilic, crosslinked polymers can retain over 90% water within the mesh of their porous network structure, thus enabling the encapsulation of hydrophilic drugs and cells. In contrast to pre-formed hydrogels, the in-situ gelation of an injectable hydrogel also allows the formation of a hydrogel encapsulated with a therapeutic payload [15–17]. Therefore, the localized delivery of a drug and/or cells can be achieved relatively more easily and less invasively than by implantation, and reach the tissues which are difficult for conventional delivery methods to reach. This type of biomaterial has been extensively studied in regenerative medicine and controlled drug release for gastroenterology, orthopedics, neurology, otolaryngology, and ophthalmology, and some hydrogel-based systems are commercially available, e.g. Re-Gel and SAR-Gel.

This article is a general summary of the most commonly used types and mechanism of the formation of in situ-formed hydrogels for ophthalmic application, focusing on their use as a delivery system for drugs and cells. This article contains a thoughtful discussion about the structure-properties relationship that determines the applications of an injectable hydrogel. We will provide details of ocular disease therapies and/or regeneration that entail the use of hydrogels, and discuss current research progress and challenges in the application of hydrogels.

2. INJECTABLE HYDROGELS

2.1 Formulation and gelation

The major components of an injectable hydrogel are hydrophilic, synthetic, or naturally derived polymers that are crosslinked in situ by a variety of mechanisms [15, 17–19]. The synthetic polymers may be crosslinked hydrophilic homopolymers or copolymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyethylene glycol (PEG), poly(N-isoproylacrylamine) (PNIPAAm), or Pluronic® F-127. PEG is a polymer of ethylene glycol, and has hydrophilic and thermoresponsive properties. This polymer is approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (the FDA) for medical use and can be easily crosslinked by several approaches; it may also form block copolymers with other polymers [15–17, 20]. PVA is a water-soluble polymer with good stability. Similar to PEG, it can be crosslinked in multiple ways and functionalized via pendant hydroxyl groups. PNIPAAm is polymerized from N-isoproylacrylamine and is also thermoresponsive, and has a low critical solution temperature (LCST) less than the physiological temperature, which allows rapid gelation [16]. Pluronic® F-127 is a copolymer of polyethylene glycol and polypropylene glycol, which is also thermally responsive and biocompatible. The major naturally derived polymers used for injectable hydrogels include polysaccharides (alginate, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid) and proteins in ophthalmology, which are biocompatible and have low toxicity [21, 22]. Alginate is an anionic polysaccharide which is a linear block copolymer of D-mannuronic acid and L-guluronic acid, and may be crosslinked by divalent ions. Its mild gelation allows the easy encapsulation of drugs, genes, and cells [22]. Hyaluronic acid (HA) is an anionic polymer composed of alternatively arranged D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine connected by a 1,4-linkage, and has an important role in the construction of ECM and the vitreous humor as well as in the regulation of cell adhesion, mobility, and angiogenesis [23]. Chitosan is a random copolymer of D-glucosamine (major content) and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine by 1,4-linkage, and has similar properties to HA. Pendant amine groups of chitosan enable chemical modification in various ways. Collagen is a major protein component of ECM with a triple helix structure and has a Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence that allows cell adhesion [23]. Gelatin is a hydrolyzed product of collagen with no triple helix structure, thus it is more soluble and more easily encapsulates macromolecules.

Generally, injectable hydrogels are divided into several classes based on the gelation mechanism: chemically crosslinked hydrogels and physically crosslinked hydrogels [15–17] (Figure 1). The chemically crosslinked hydrogels utilize a chemical crosslinking reaction, and the most commonly used reactions include Michael addition, Schiff base formation, the Diels–Alder reaction, click chemistry, and enzyme reactions to effect in situ, covalent crosslinking, and formation of a matrix macromolecular structure [17, 24–27]. Physically crosslinked hydrogels are formed by changes in physico-chemical parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, ionic strength, the glucose concentration or mechanical stress) as stimuli for conformation changes of polymers and cause phase separation, thus the aggregation of polymer chains forms a physically crosslinked network [21, 28]. This type of hydrogel incorporates stimuli-responsive polymers in ophthalmic application, including thermo-responsive PEG, PNIPAAm, Pluronic® F-127 and hydroxymethyl cellulose, and pH-responsive polyacrylic acid (PAAc) and chitosan [29–34]. Furthermore, ionic crosslinking (e.g. divalent ions crosslinked alginate or fibrin with factor xiii) and supramolecular interactions (e.g., cyclodextrin) have been used for forming injectable hydrogel [16, 35–38]. The features of these materials and related gelation approaches are summarized in table 1. A more detailed classification and the introduction of materials are available from other publications [15, 16, 38].

Table 1.

Summary of major polymer components in ophthalmic injectable hydrogels

| Type | Polymers | Gelation method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic polymers | PAAc[16] | pH changes | Controlled swelling behavior | Cytotoxicity and cause inflammation |

| PEG[20] | Temperature, chemical crosslinking | Easy to crosslink, biocompatible, stable | Non-biodegradable, gelation behavior may vary | |

| Pluronic F-127[20] | Temperature | Biocompatible, controlled properties | Non-biodegradable, weak mechanical properties and stability | |

| PNIPAAm[20] | Temperature | Easy gelation below physiological temperature | Non-biodegradable, toxic degradation product | |

| PVA[19] | Chemical crosslinking | Stable, biodegradable, biocompatible | Not stimuli-responsive, crosslinkers maybe toxic | |

| Naturally derived polymers | Alginate[17] | Chemical and/or Ionic crosslinking | Biocompatible, rapid gelation, good mechanical properties | Poor cell adhesion |

| Chitosan[17] | Chemical crosslinking, pH changes | Similar to hyaluronic acid, easy to modify | Poor solubility at neutral pH | |

| Collagen[85] | Chemical crosslinking, Temperature (must be denatured) | ECM component, cell adhesion, biocompatible | Difficult to dissolve, susceptible to degradation | |

| Dextran[20] | Chemical crosslinking | Biocompatible, easy to crosslink, large capacity | May cause side-effect in vivo | |

| Gelatin[16] | Chemical crosslinking | Easy to dissolve, multiple reaction available, biocompatible | Weak mechanical properties, susceptible to degradation | |

| Hyaluronic acid[17] | Chemical crosslinking, temperature (with other polymers) | Easy modification, ECM/vitreous component, bioactive | High viscosity, susceptible to degradation |

2.2 Hydrogel structure and payload release

As delivery vehicles, the hydrogel structure can be engineered in its chemical and/or physical aspect for extended payload release from the polymer matrix [39]. For a low molecular weight substance, the release generally follows the model of diffusion from a matrix, and provides rapid drug release from hours to days, especially for hydrophilic drugs [39]. Enhancement of the electrical charge arising from functional groups or hydrogen bonds may also improve the affinity of a hydrogel for a hydrophilic drug. Thus, such drugs may be loaded in a large quantity and achieve a sustained release. The addition of hydrophobic polymers may prolong the lifespan of a hydrophobic drug directly dispersed or loaded in a liposome or cyclodextrin [40].

For covalently bonded and encapsulated biomacromolecules, nanoparticles, or cells, the payload release is effected by surface erosion or the bulk degradation of the gel matrix, rather than diffusion from the hydrogel. Therefore, the injectable hydrogels may be engineered to have a desirable lifespan of weeks or months by controlling the degradation rate [39]. The delivery cells pose an additional requirement for the hydrogel structure, and the involvement of the integrin recognition sequence and glycoprotein receptors may improve the behavior of encapsulated cells for delivery [41].

The swelling behavior of pH responsive polymers (e.g. PAAc) has been employed to obtain a controlled release of both small molecules and macromolecules. The molecular weight of a polymer between two crosslink points and the mesh size are most critical properties that control the swelling behavior, the drug release rate, and oxygen permeability. The Flory-Rehner theory has been used to determine the swelling behavior of a hydrogel and a more elaborate model for hydrogel swelling behavior was created on this basis to understand the gelation in water [42]. The equation can be written as:

| (1) |

Where Mc is the average molecular weight of the polymer between two chains after crosslinking, Mn is the number average molecular weight of polymer before crosslinking, ν2,s is the volume fraction of polymer in swelling state, ν2,r is the volume fraction of polymer at relaxed state (after gelation but before swelling), V1 is volume of water and ν̄ is specific volume of the polymer, and χ1 is the interaction parameter between the polymer and water.

The swelling ratio of hydrogels Q is inversed volume fraction of polymer in swelling state. For super-swollen hydrogels (Q>10), swelling ratio can be described as:

| (2) |

Therefore, the Mc governs the swelling behavior of hydrogels. The mesh size ζ is related to Mc, which is another parameter to represent the porosity of the hydrogel and determine the release rate from the hydrogel. The mesh size can be determined by the following equation:

| (3) |

Where is the squared mean of end-to-end distance of network chain between two adjacent crosslinking sites, Mr is the molecular weight of polymer repeating units, Cn is Flory characteristic ratio (8.8), and l is the distance between two carbon atoms (1.54Å).

By selecting the types of monomers and/or polymers, the polymerization or crosslinking reaction route, and the concentration of the reactant in the synthesis, the structure of an injectable hydrogel can be well defined and utilized for controlled release. The drug release from hydrogel with consideration of factors of polymer relaxation and drug diffusion can be characterized by the Ritger–Peppas equation [42].

Where is the fraction of released drug, k is proportionality constant, t is release time, and n is release mechanism related diffusion exponent.

Although the drug release model from a hydrogel has been well defined, it is still challenging to determine the drug release characteristics using mathematical methods due to the irregular geometry of gelation and the uneven distribution of a drug within a hydrogel [40]. Furthermore, several biomacromolecules may become denatured within an injectable hydrogel during delivery, thus reducing the overall availability of the payload, which renders it more difficult to estimate the drug release amount and the rate.

2.3 Criteria of injectable hydrogel design for ophthalmic fields

Similar to other biomaterials, the application of an injectable hydrogel for drug delivery and regenerative medicine has requirements in biocompatibility, non-toxicity, non-inflammation, non-immunogenic, biodegradability, stability, matching mechanical properties with natural tissues, and is application-specific. Moreover, formation of an injectable hydrogel must be conducted in a benign environment which is free from the production of excess gas, protons, heat, or substances hazardous to living organisms, and the gel must form under physiological conditions of temperature and ionic strength in a controllable manner.

A few additional criteria of functions are proposed for biomaterials for ophthalmic applications. First, a hydrogel should have the capability to be functionalized to meet the needs of different applications, and must be able to be applied using a thin needle (i.e., 30-gauge or thinner) in the restricted space of the eye [43, 44]. The hydrogels that are developed as drug delivery system should be able to encapsulate a drug at a high concentration and provide a sustained release from the crosslinked network, although an initial burst release is inevitable. Therefore, the in situ crosslinking of a hydrogel must not affect its chemical properties or the availability of a drug within the matrix, and the hydrogel must be engineered to meet the drug release requirement by controlling the aforementioned factors [45]. Moreover, transportation of cells for the posterior segment may require an injectable hydrogel to adhere a cell by non-specific or specific binding, and have an adequate pore size for the exchange of nutrients and the migration of cells. Additionally, a hydrogel should provide mechanical support and guide the differentiation of stem cells or adult cells laden with growth factors [46]. Aside from the above, a high water content, tissue adhesion, and gas permeability are prerequisites for desirable wound healing materials for ocular surgery or intravitreal injection [25]. Last but not least, transparency and a refractive index similar to the human eye are highly preferred, especially for application to the front of the eye for the substitute of the vitreous (refractive index of approximately 1.42), and other physiological conditions of the eye (e.g. the eye flow and intraocular pressure (IOP)) should not be significantly changed during and after the injection of a hydrogel [13, 45].

3. INJECTABLE HYDROGELS IN OPHTHALMIC TREATMENT

Major ophthalmic diseases and disorders include age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cataracts, cancers, corneal wear, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, inflammation, keratoconus, retinal detachment, and retinitis pigmentosa. The following section is a summary and a discussion of the progress on the research on injectable hydrogels in the treatment of the aforementioned diseases and disorders.

3.1 Corneal abrasion and keratoconus

3.1.1 Cause of disease and treatment

The epithelial surface of the cornea is vulnerable to mechanical wear and may cause temporary pain and reduced vision. The light abrasion may be restored by the reconnection of epithelium cells, but severe damage may require antibiotics and a sealant to prevent infection and further damage. Keratoconus is a common progressive degenerative eye disorder with structural changes in thinning cornea, and causes a conical shape of cornea thus deflect the light way to the retina. The severe distortion of vision, streaking, and sensitivity to all light are the common symptoms in the keratoconus patient [47].

3.1.2 The hydrogels in treatment

The in-situ formed hydrogel is also an effective approach for delivery due to the ease of delivery and the long-term dosage retention [48], and the hydrogel can be used to repair and seal corneal wounds. The PEG-based homopolymers and copolymers are ideal for this purpose. A PEG-based doxycycline laden transparent hydrogel can be formed in situ rapidly using thiol reaction and evaluated for their wound healing application. The PEG hydrogel can resist the deformation under shearing force and prolong the release of drug up to 7 days. A significant reduction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) was demonstrated by immunofluorescence studies and histology studies, which exhibited superior corneal healing compared to conventional topically administered solution [49]. In another study, the thermoresponsive copolymer of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) and PEG was used for corneal wound healing. A hydrogel underwent sol-gel transition at a temperature higher than the room temperature at a 35% weight concentration, and a biocompatible hydrogel facilitated the migration of epithelial cells [50]. Studies in a rabbit model revealed desirable pocket healing with little evidence of scarring and normal keratocyte appearance.

Stem cells have also been utilized for the regeneration of a worn cornea. A study of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with a thermoresponsive injectable carboxymethyl-hexanoyl chitosan (CHC) hydrogel discovered that the cell viability and cluster of differentiation (CD) 44+ proportion of iPSCs were increased. The wound healing in abrasion-injured corneas was facilitated by the combination of stem cells and the hydrogel. The study also found that the CHC hydrogel has effects in reducing the reactive oxygen species (ROS) and restoring the corneal epithelial thickness, thus further improving the reconstruction of damaged cornea. The CHC hydrogel shows a potential as a stem cell delivery system for the enhancement of corneal wound treatment [51].

Current treatment of keratoconus includes cornea transplant surgery and corneal collagen crosslinking by Riboflavin/UV light [52]. A PEG injectable hydrogel containing Tyr-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (YRGDS) peptides was developed as a culture system for studying corneal keratocytes [53]. Keratocytes encapsulated in hydrogels remained viable for over 4 weeks with desirable morphology, and a hydrogel can support the production of collagen, biglycan, keratocan, and related DNA. However, the hydrogel failed to restore the keratocyte phenotype but merely stabilized the phenotype. Therefore, the keratocytes cultured in three-dimensional (3D) PEG hydrogel still need further investigation to translate to cell-based therapeutic method for keratoconus.

3.2 Cataracts

3.2.1 Cause of disease and treatment

Cataracts are the greatest cause of blindness worldwide, and over 50% of blindness and 30% of vision impairment are the result of cataracts. The cause is a slowly developing clouding of the lens of one eye or both eyes [3]. This disease is considered a consequence of aging and other factors (e.g. trauma, radiation, and excessive exposure to sunlight). The current treatment of cataracts is surgical, i.e., the removal of the cloudy lens [54]. Hydrogels have been used as a replacement lens after surgical incision, and have similar requirements as the previously discussed corneal surgery sealants. An injectable hydrogel was approved by the FDA as a cataract surgery sealant in 2014.

3.2.2 Hydrogels as sealant

Synthetic polymers work better than naturally derived polymers as wound dressings and sealants. PEG hydrogel polymers are primarily used, because they have a long safety record, biocompatibility, and a high water content, which is similar to that of the eye. PEG–based hydrogels can be engineered to meet mechanical and biological requirements for applications as a sealant [16]. Studies exist on the PEG polymerized adherent ocular bandage during transient fluctuations of the IOP [55]. The PEG-based formulation (the ReSure® sealant from Ocular Therapeutix) has been approved by the FDA and studied in multiple cases [56]. Fibrin is a promising material for wound healing because it has a natural role in hemostasis. Fibrin may form a gel in the presence of Ca2+ via the crosslinking of fibrinogen. Several commercial products are currently available as tissue sealants (e.g. Tissucol®). This type of material is mainly used for topical usage in eye incisions.

3.2.3 Hydrogels as a lens replacement

Meanwhile, injectable hydrogels have been studied for replacement of the lens. This type of hydrogel requires similar refractive index with natural lens (1.42), stable swelling behavior, and matching mechanical properties. Conventionally, siloxane polymer was designed for implementation as an injectable intraocular lens and it has a consistency suitable for injection into the empty lens capsule [57]. However, the siloxane-based materials as a replacement of the lens may not well match the sturdiness of the natural lens [57].

A photon reaction using irradiation with blue light was also employed to create potential hydrogels for this application. Low molecular weight poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylates (PEGDA) and high molecular weight copolymer of N-vinylpyrrolidone and vinyl alcohol (PVP-PVA) with light reactive acryl groups were crosslinked via blue light irradiation [58]. A hydrogel allows comparable transparency to a range of 300–800 nm wavelength light with the natural adult (25-year old) lens; however, the refractive index of these hydrogels is 1.40 at optimized condition, which is lower than the 1.42 of natural lens. The hydrogels with optimized PEGDA and PVP-PVA ratio had no significant mass loss (1 %) and swelling (4 %) after they were formed.

Although low viscosity of the polymer solution caused leakage when injected into the pig capsular bag, the studies inspired the development of injectable hydrogels with similar formulation. Moreover, this approach avoids use of hazardous UV for hydrogel crosslinking by replacing it with blue light, although the cytotoxicity of the photo initiator remains an underlying issue and blue light still may damage the retina.

Acrylamide hydrogels with thiol groups were polymerized and broken down for crosslinking. The hydrogel precursors were crosslinked via Michael addition, and the moduli of a hydrogel are controlled in a range of 0.27 to 1.1 kPa using different reactant ratios, which may be similar to the natural vitreous humor [59]. An optically clear gel could be rapidly obtained within the lens capsular bag. In a rabbit study, the hydrogel was demonstrated to be transparent and stable for 9 months [59].

3.3 Glaucoma

3.3.1 Cause of disease and treatment

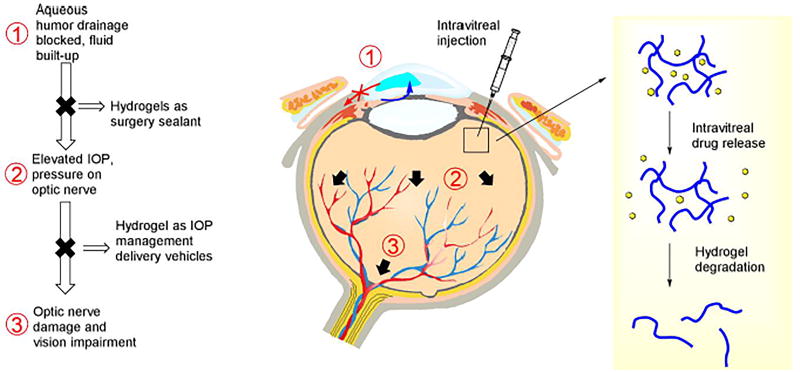

Glaucoma is the second major cause of blindness in the world after cataracts. It is caused by increasing intraocular pressure with imbalance between aqueous humor production and drainage of aqueous humor via trabecular meshwork and scleral venous sinus (Figure 2), thus putting pressure on the optic nerve that results in the impairment of the nerve system and a loss of vision [60, 61]. Medications such as Timolol Maleate, Xalatan, and pilocarpine are commonly used for glaucoma treatment in the form of eye drops. However, conventional administration methods such as eye drops have a drawback of low bioavailability (less than 5%) and intravitreal injections have a relatively short retention time; therefore, hydrogels may provide sustained release and improve bioavailability [7, 62]. For instance, OTX-TP from Ocular Therapeutix is under phase 3 clinical trial for treatment of glaucoma. There are also microcatheter-based drainage and laser-based surgical methods in medical practice that use a hydrogel as a sealant of incursion similar to cataract surgery [63].

Figure 2.

Pathophysiology of glaucoma and current treatment with injectable hydrogels.

3.3.2 Drug delivery

The delivery of IOP management drugs utilize both synthetic and naturally derived injectable hydrogels. A thermoresponsive copolymer, PNIPAAm–chitosan (CS), has been investigated for ocular drug delivery. PNIPAAm–CS featured a low critical solution temperature (LCST) of 32 °C, which is lower than physiological temperature [31]. Timolol Maleate, a useful drug in glaucoma treatment, was studied with the hydrogel and showed a release profile with larger area under the curve compared with conventional eye drops, and reached final concentration of 11.2 µg/mL. The MTT assay showed the minimal toxicity of a Timolol Maleate-laden hydrogel with 0.5–400 g/mL concentration of polymers. The PNIPAAm–CS hydrogel has the potential to extend the drug released into a glaucomatous eye and more effectively reduce IOP than conventional eye drops.

In another study, gelatin was grafted with carboxylic end-PNIPAAm via a carbodiimide coupling reaction in situ to produce a delivery system which was designed for the administration of intracameral anti-glaucoma medication [64]. The hydrogel had superior thermal gelation and adhesion and was biodegradable in the presence of an enzyme. Cytotoxicity studies suggested that the anterior segment with in situ forming gels had good proliferation and minimal inflammation. The hydrogel had a high encapsulation (~62%) and cumulative release ratio (~95%), and the subsequent degradation of the gelatin network was progressive [64]. The in vivo efficacy of the delivery carrier was evaluated in a rabbit glaucoma model, and the intracameral administration of pilocarpine using a hydrogel was found to be more effective than traditional eye drops and injection of free drug. Furthermore, the hydrogel extended the reduction of IOP and pharmacological responses related to reduced-IOP, such as miotic action and stable corneal endothelium density.

Gelatin and chitosan can be crosslinked using different agents, including genipin which was tested to deliver Timolol Maleate. The gelatin and chitosan gels obtained with the aid of genipin were safe and useful for the controlled intraocular drug release [26]. The alginate was employed as a rapidly forming injectable hydrogel, and was consequently used to release pilocarpine and Kelton LV [35]. In vitro studies indicated that pilocarpine was released slowly from an alginate gel via diffusion from the gel and the guluronate residue ratio of alginate governed the release rate. The rabbit eyes were treated with injectable hydrogel composed of alginate loaded with pilocarpine, and the lowered IOP indicated significant extension of the pressure-reducing effect.

An amphiphilic chitosan-based thermogel with a shear-reversible colloidal system was developed to improve release duration of latanoprost as anti-glaucoma drug and benzalkonium chloride as the preservative [32]. The incorporated substances and preparation procedure have an impact on the mechanical and drug release properties. The release of the drug loaded in a colloidal carrier may not occur via diffusion within the gel but limit the transport within the gel. A gel has potential, because it is easy to prepare and administer, has low cytotoxicity, and effectively lowers the IOP for 40 days in a rabbit glaucoma model. PNIPAAm in linear polymer formation crosslinked with PNIPAAm/epinephrine nanoparticles was also studied for anti-glaucoma therapy [65]. However, the hydrogel system only extends epinephrine release to 32 h, which is considerably shorter than the release period of delivery systems containing both natural polymer and PNIPAAm.

3.3.3 Stem cell treatment

The development of stem cell treatments for glaucoma has made some progress in recent years. The cell therapy using stem cells is promising for both replacements of lost cells and protection of damaged cells, especially the vulnerable trabecular meshwork and retinal ganglion cells [66]. Embryonic stem cells (ESC), iPSC, and adult stem cells show promise as therapeutic approaches. The glaucoma therapies using commercialized stem cells are being conducted at some institutions, although safety and ethics are still the concerns [66]. The injectable hydrogels have been studied as the delivery vehicle for stem cells, and human iPSC/ESC cultured within an alginate-RGD hydrogel were shown to maintain cell survival for 45 days and upregulate the expression of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) markers (TYR and RPE65) and retinal ganglion cell marker (MATH5) [67]. More discussion in detail along with other diseases in the following section (e g. Diabetic retinopathy and AMD).

3.4 Retinal detachment

3.4.1 Cause and treatment of the disease

Retinal detachment is caused by fluid leaking behind the RPE, and the treatment includes removal of the vitreous humor and filling it with other materials [4, 68]. The surgical treatment for retinal detachment requires vitreous tamponade-like agents to fill the volume and restore the IOP, allowing the detached neurosensory retina to attach to the RPE. The most commonly used vitreous tamponade agents in clinical surgery include sulfur hexafluoride, perfluorocarbon gasses, perfluorocarbon liquids, and silicone-based oils [68]. However, no material is currently clinically available as a long-term vitreous substitute. The development of a substitute for the vitreous body remains challenging in ophthalmology research but is interesting to investigate. A hydrogel may be a superior choice as a substitute for the vitreous humor by employing a polymer solution to fill a potential irregular cavity using a minimally invasive technique, providing a similar refractive index and viscosity as the natural vitreous humor [69].

3.4.2 Hydrogels as vitreous substitutes

The PEG and PVA-based injectable hydrogels are desirable candidates for their stability, optical transparency and matching mechanical properties. In a study, the foldable capsular vitreous body (FCVB) was injected with a PVA hydrogel to serve as a long-term vitreous substitute. The PVA hydrogel was crosslinked by gamma irradiation and showed good viscoelasticity and biocompatibility on L929 cell lines, and maintained constant IOP and retinal morphology. The hydrogel inside the FCVB remained transparent and supported the retina 180 days after injection. The PVA hydrogel with improved stable performance may be utilized as a vitreous substitute; however, gamma radiation crosslinking has to be carefully handled [70].

Another example reported an injectable vitreous substitute composed of thermosensitive amphiphilic polymer poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (PEG-MA), which could form a transparent gel in situ [71]. The hydrogel allows more transmission of visible light compared to natural vitreous and exhibits mechanical stability under temperature changes and shearing force. The hydrogel was biocompatible both in vitro and in vivo, and kept IOP at a desirable level. Furthermore, an in-situ gelation system based on α-PEG-MA and a redox-initiated radical crosslinking reaction was developed as a vitreous substitute [72]. The studies characterized reaction kinetics, gelation time, rheological properties, and swelling behavior in detail. It has been shown that the system formed a transparent gel in the vitreous cavity, and the inflammation response caused by injection could be controlled in a rabbit model.

In another instance, hydrogels were synthesized using a photo-initiated reaction of HA with adipic dihydrazide (ADH) [73], and clear and transparent hydrogels with a refractive index similar to human vitreous humor were obtained. A degradation test only observed a small fraction of mass loss in 1 month. Different from other photo crosslinked hydrogels, the cytotoxicity induced from the hydrogel and apoptosis in the RPE cells can be minimized, although using photoinitiator still has underlying risk. The UV crosslinked gels may remain stable and functional in place for 6 weeks in vivo. A hydrogel from a tetra-arm thiol ended PEG cluster was crosslinked by maleimide, and rapid gelation was performed with a low polymer concentration (4.0 g/L) [74]. The transparent injectable hydrogel was non-toxic and non-inflammatory and had no significant swelling behavior in a rabbit retinal detachment model. The hydrogel remained clear and provided retinal support for 410 days, which proves the superiority of a PEG-based injectable hydrogel to conventional vitreous filling materials.

3.5 Retinitis Pigmentosa

3.5.1 Cause of disease and treatment

Retinitis pigmentosa is an inherited disease caused by the degeneration of the rod photoreceptor cells. The mutations of rhodopsin gene lead to the majority of retinitis pigmentosa in autosomal dominant form, and mutation of other genes (USH2A, RPGR, and RP2) causes autosomal recessive or X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Currently, the treatment of this disease remains a challenge with conventional approaches. Research has focused on the regeneration of the diseased retina using a variety of cell types for transplantation. The stem and progenitor cells were injected into the vitreous or sub-retinal space in early studies, and these donor cells were expected to migrate to the degenerated retina sites and integrate with retina, eventually restoring vision of patient [23, 75]. However, the bolus injection failed to obtain localized tissue grafts in aforementioned studies. Thus, conventional two-dimensional (2D) substrates were not effective in stimulating neural regeneration in vivo, and a 3D structure would be highly preferable. The transplantation of stem cells to adult models has been limited due to their low survival rate and the problem of integration, therefore a hydrogel played a critical role in regeneration of the retina [76, 77]. Meanwhile, the gene delivery using an injectable hydrogel has also been studied as a treatment for retinitis pigmentosa [9, 10].

3.5.2 Gene delivery, drugs and stem cells

Genes in a variety of forms have been delivered to the retina for the treatment of retinitis pigmentosa [9, 10]. Pluronic F-127-based hydrogels have been studied for gene delivery as a treatment of retinitis pigmentosa [33]. The delivery to RPE did not decrease in the transduction efficiency compared to traditional methods, and also no toxicity has been observed in transduced 293T cells. The hydrogel can provide treatment for retinal diseases via localized and sustained delivery of dexamethasone across human sclera. However, limited biocompatibility was suggested from tissue damage and an increase in activated macrophages. A hydrogel composed of PEG and poly(l-lysine) (PLL) has controllable mechanical properties and supports the migration, survival, and differentiation of retinal ganglion cells and amacrine cells. This research may provide a future solution for engineering CNS tissue for retinal regeneration [78].

Thermoresponsive hydrogels from PNIPAAm, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), AA and acryloyloxy dimethyl-γ-butyrolactone (DBA) were synthesized for posterior segment therapeutic payload delivery. The increase in the DBA content of a hydrogel reduced the water content and lowered the critical solution temperature. Although the gelation took some time, the gels degraded slowly, and over 85% of the mass remained after 4 months. These hydrogels are promising as delivery vehicles to provide localized release to combat retinal degenerative diseases [79].

The oxidized dextran crosslinked with adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogels were synthesized without using the initiators and produced an injectable hydrogel for drug delivery to the posterior eye segment [80]. The degree of dextran oxidation and the concentration of two components governed gelation and degradation rate of hydrogels. Higher oxidized dextran content is proven to improve cell adhesion and proliferation compared to lower concentrations. Hydrogels are non-toxic and biodegradable but still need further investigation in vivo.

Several clinical trials using retinal stem cell (RSC) were run, and the migration and differentiation of stem cells were obtained after direct injection [81, 82]. However, the differentiation and migration of injected stem cells must be significantly improved, and cell degeneration after injection must be resolved. An injectable hydrogel for stem cell delivery was developed from a copolymer of hyaluronan and methylcellulose (HAMC). The hydrogel precursors can be injected with 34-gauge syringe, and gelation was conducted in a rapid manner with absence of significant swelling. HAMC hydrogels improved cell viability and integration of RSC-derived rods via the interaction with the CD44 receptor, and also improved the distribution and regeneration of neural stem and progenitor cells. This delivery system proved the concept that a hydrogel improves cell transplantation efficacy in animal models, but the functionality of the regenerated RPE must be further investigated [83, 84].

Thermoresponsive and bioactive hydrogels from type I bovine collagen and amine ended PNIPAAm were crosslinked by using 1-ethyl-(3-3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and designed for the delivery of RPE cells into the posterior segment for retinal degenerative diseases treatment [85]. Hydrogel scaffolds display a rapid phase transition at physiological temperature and can deliver cells with minimal cytotoxicity. RPE cells loaded at room temperature avoid the problem of cell repulsion, and RPE cells were well trapped in hydrogel scaffold. Another formulation using NHS and NIPAAm with HA and modification obtained similar results with RPE cells [86]. However, no further studies followed using thermoresponsive hydrogels in any animal models.

3.6 Diabetic retinopathy

3.6.1 Cause of disease and treatment

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is caused by choroidal blood vessel damage from diabetes which finally leads to partial or complete loss of vision. Treatment includes laser surgery, corticosteroid injection, and anti-angiogenesis treatment. The monoclonal anti-VEGF drugs Avastin® (Bevacizumab), Lucentis® (Ranibizumab) and Eylea® (Aflibercept) are the most commonly used drugs for DR. A wet AMD treatment in the clinic is a recent anti-angiogenesis treatment; however, it has a short lifespan via intraocular injection, and required repeated delivery. An injectable hydrogel may improve delivery efficiency and render sustained delivery. Current research on DR focuses on improving delivery efficiency of anti-VEGF and diabetic management drugs (heparin and some growth factors) for diabetes treatment, as well as for stem cells for regeneration in the future [81, 87, 88]. The hydrogel-based VEGF delivery system will be discussed along with AMD.

3.6.2 Drug Delivery

The fibrin with a bi-domain peptide incorporated has a drug release profile which is controlled through reversible binding, and the system can form a gel in situ [88]. The peptide sequesters affinity to heparin within the matrix and can slow the release of any heparin binding protein such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) because it reversibly binds the heparin. This fibrin gel has been tested as the controlled delivery vehicle of multiple factors, and the peptide sequences affinity to heparin can slow the release of protein reversibly bind the heparin [88].

A recent study introduced an ECM-derived hydrogel for heparin and growth factor delivery [89]. The system immobilizes growth factors on a hydrogel using a variety of interactions (e.g. chemical bonding or growth factor binding domains) to increase their stability and activity. The hydrogel with sulfated glycosaminoglycan content in a study was derived from a decellularized pericardial ECM and could bind with fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). Delivery of bFGF both in vitro and in vivo from a hydrogel increased the retention compared to the delivery in standalone collagen. An intramyocardial injection in a rodent infarct model showed improved neovascularization, and the newly formed blood vessel was anastomosed with the existing vasculature. Thus, a decellularized ECM hydrogel provided a platform for the incorporation of heparin-binding growth factors for the regeneration of the retinal structure.

3.6.3 Stem cell treatment

It has been suggested that the retina can be regenerated with stem cells. The differentiation of ESC/iPSC has several steps, from retinal progenitor cells (RPC), to photoreceptor precursors, and finally to photoreceptor cells [90]. The delivery of the RPC into the retina remains a challenge, and the survival, delivery, and differentiation of cells must be controlled for diabetic retinopathy. An injectable hydrogel may play the role of a delivery vehicle, mechanical support, and a reservoir for factors. HA is perceived to play a role in morphogenesis, cell proliferation, inflammation, wound repair, and other cellular processes. The interaction with cells primarily through CD44 and hyaluronan-mediated motility (RHAMM) developed a stem cell delivery system that used the HAMC with injectable, biodegradable, and minimally invasive properties [84]. The HAMC hydrogel was injected in a murine model to assess their biodegradability and capability as a cell delivery vehicle. RSPC delivery in HAMC is significantly better than saline distributed in the subretinal space.

HA-based injectable hydrogels can comprise an injectable delivery system through encapsulating the mouse RPC cells. RPCs were maintained undifferentiated within a hydrogel, and the hydrogel was completely degraded by 3 weeks and the RPCs were evenly distributed in the subretinal space. The released RPC remained viable when expressed in the recoverin (a mature photoreceptor marker). The hydrogel with benign properties provided a beneficial environment to support cell survival and proliferation, and differentiated RPCs allowed for the regeneration of damaged photoreceptor cells[91].

3.7 Age-related macular degeneration

3.7.1 Cause of disease and treatment

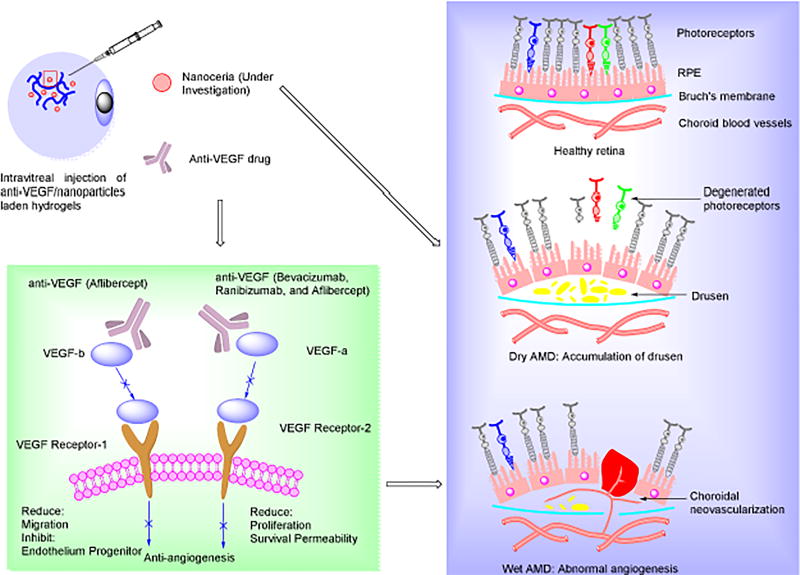

AMD is the most commonly seen age-related ocular disease in the western world, is most prevalent in those over 55 years of age, and results in visual deficits [81, 92–94]. AMD can be divided into two categories: atrophic (as known as dry AMD, 90% prevalence) and exudative (wet AMD, more severe) AMD. Dry AMD is a consequence of drusen accumulation, and the wet form is associated with abnormal angiogenesis (Figure 3). Currently, no effective treatment exists for dry AMD, and wet AMD may be treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs with injections directly into the eye once a month, with no approach to recover lost vision [95–97]. Similar to DR, anti-angiogenesis approaches are effective in preventing the progression of the disease and have been approved by the FDA for wet AMD treatment. However, the recovery of lost or impaired vision remains elusive. Recent studies have revealed that ROS is associated with both dry and wet AMD, thus controlling ROS may become an effective approach to prevent the progression of AMD [98]. The long-term sustained intraocular delivery of robust antioxidants and/or antiangiogenic agents may be considered as the best option for both dry and wet AMD [99].

Figure 3.

Left panel: Schematic diagrams of injectable hydrogel-mediated antiangiogenesis/antioxidant treatments for Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD); Right panel: Schematic illustration of AMD pathophysiology: dry AMD is caused by accumulation of drusen under Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) cell layer and wet AMD is associated with acute abnormal angiogenesis under RPE, finally resulting in rupture of RPE cell layer with photoreceptor. The injectable hydrogels with anti-VEGF drug are used in intravitreal injection for wet AMD treatment, and nanoceria treatment of both dry and wet AMD are under investigation in our laboratory.

3.7.2 Anti-VEGF and antioxidant delivery

The sustained release of Avastin from a hydrogel composed of block polymers of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone)-b-poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) (PEOX-PCL-PEOX) was reported. The block polymers are synthesized in 3 step reactions, and the hydrogels may be biodegradable in vitro and have minimal cytotoxicity in a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line [100]. The histomorphology and electrophysiology were studied in rabbits and the neuroretina was preserved after 2 months of intravitreal injection. In another instance, the administered intravitreal release profile of bevacizumab from poly(ethylene glycol)-poly-(serinol hexamethylene urethane) (ESHU) hydrogel was also studied for 9 weeks, and over 4 times higher than in eyes that received bevacizumab through bolus injections. No significant elevation in the IOP was noted after injection, nor any severe inflammatory reaction [45]. Compared to the conventionally used PEG-PCL-PEG or PEG-PLA-PEG hydrogels, the ESHU hydrogel and its degradation products were more biocompatible (absence of lactic acid), and the structure may have a stronger affinity for protein and peptide structures. Thus, the development of such suitable materials may proceed in the treatment of wet AMD. Moreover, the four-arm PEG were crosslinked via the maleic and thiol end groups of the PEG chains in situ, and this type of biocompatible hydrogel may be used for Avastin delivery in vivo. A sustained released was obtained within 14 days, and over 70% of the drug was released during a release test. Further investigation of the long-term release and hydrogel degradation has not been done and further studies are still required [101]. It seems as if the standalone PEG chains may not meet the long-term release requirements for antibody drugs.

An injectable hydrogel was developed from alginate and chitosan for the potential intraocular delivery of antibody drugs. This polysaccharide cross-linked hydrogel had a degradation rate associated with the oxidized alginate content. Encapsulated Avastin had an initial burst release from hydrogels and then sustained release in 3 days, and the increase of the oxidized alginate concentration lowered the release rate of Avastin from the hydrogel [102]. Another hydrogel was developed from vinylsulfone functionalized hyaluronic acid (HAVS) and thiolated dextran (Dex-SH) via Michael addition for intravitreal bevacizumab delivery. The material was biocompatible as confirmed by multiple methods, including IOP measurement, ophthalmoscope, full-field electroretinography (ERG), and histological studies [103]. The hydrogel prolonged the release of bevacizumab in a rabbit model and maintained an effective therapeutic concentration for over 6 months. Photo-responsive polymer coated gold nanoparticles were encapsulated in agarose hydrogels, and the release rate of the bevacizumab load could be controlled with the light intensity and the exposure time [104]. A hydrogel prolonged the release and increased the bioavailability of an anti-VEGF antibody drug in a bovine model.

Some preliminary research has been done on using nanoceria as an antioxidant [99, 105], which may protect retinal function and RPE cells as well as reducing ROS-related inflammation. Recent strategies in our group for the treatment of age-related diseases with an injectable hydrogel as a delivery vehicle involved the delivery of anti-VEGF and antioxidative nanoparticles (Figure 3).

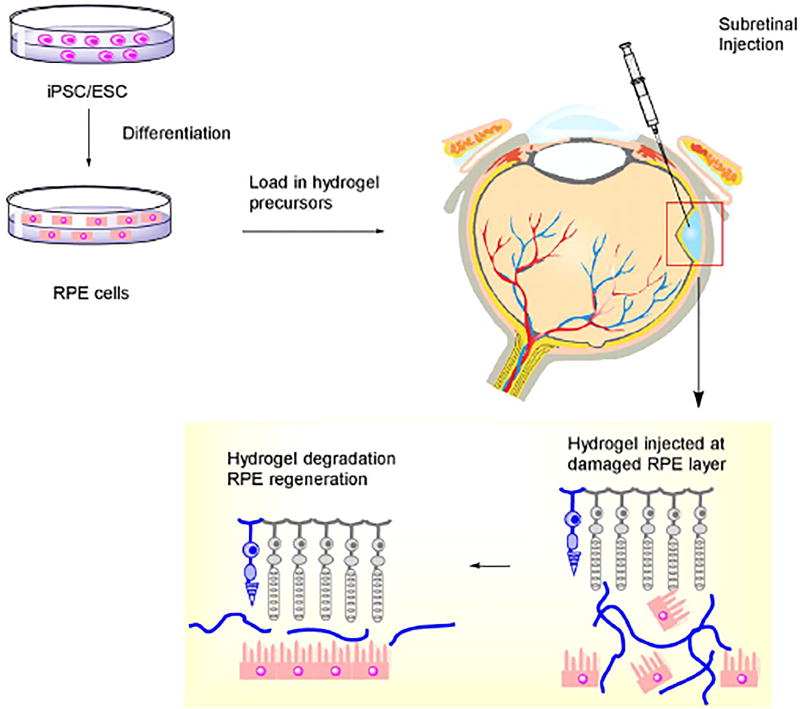

3.7.3 Stem cell treatment

Similar to DR, an alternative treatment strategy under investigation for dry AMD utilizes the transplantation of RPE or photoreceptor cells [81]. The approach involves the delivery of RPE cells under the retina to restore damaged vision (Figure 4). The injection of RPE cells into the subretinal space seems to be promising, although post-injection cellular positioning and cell viability may be issues. The use of an injectable hydrogel for cell delivery may overcome those issues by providing physical support for cells and preventing cell death [81, 83]. Also, transplantation may be conducted in a minimally invasive way, without surgery in RPE sheet implantation. Furthermore, it has been found that ESC/iPSC is capable of replacing damaged retinal cells. Neural stem cells (NSC) may potentially become replacement cells and be mediators of treatment. Injectable hydrogels based on alginate, collagen, or chitosan are being developed, and show a continuous, slow and low in vivo release over several weeks [17, 76, 81]. However, the loading capacity of a hydrogel is limited, thus during the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as AMD, and repeated injection of hydrogel for sustained release remains a great hurdle to FDA approval. Safety issues (incidence or adverse events) occurred in an earlier trial of stem cell treatments, which rendered this potential therapy more unpredictable [81, 83].

Figure 4.

Stem cell treatment with an injectable hydrogel for retina photoreceptor regeneration.

3.8 Inflammation

Eye inflammation is found in a variety of forms such as keratitis, uveitis, iritis, scleritis, chorioretinitis, conjunctivitis, choroiditis, retinitis, and retinochoroiditis. However, the poor bioavailability and therapeutic effects of conventional administration techniques remain a problem in inflammation treatment. Novel treatments with hydrogels entail the delivery of antibiotics and other drugs.

The Gelrite gellan gum-based in situ forming systems undergo a sol-gel transition and have been evaluated as an ophthalmic delivery system for antibiotics [106]. This hydrogel system may improve therapeutic efficacy and provide the prolonged release of ciprofloxacin over an 8-hour period in vitro.

Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea and the neuro-retinal area, ultimately leading to severe vision loss and morbidity. The latest therapy involves the use of rhodamine-conjugated liposomes loaded with vasoactive intestinal peptide released from commercial hyaluronic acid hydrogels (Provisc and HA Acros) [107]. Studies show that the increased viscosity and reinforced elasticity of hydrogels was caused by interactions between the hydrogel moieties and the liposomes. In vivo studies showed that the conjugates released from the hydrogels significantly reduced the inflammatory response, and prolonged the drug release.

A PEG-PCL-PEG triblock copolymer was thermoresponsive and formed a gel at physiological temperature [108]. The evaluation of PEG-PCL-PEG hydrogel toxicity indicates that the hydrogel is biocompatible. The PEG-PCL-PEG hydrogel is biodegradable in the eye, and it does not affect cultured human lens epithelia, IOP, and other ocular tissues. However, a temporarily elevated IOP and slight corneal endothelial damage were found at some specific conditions.

3.9 Intraocular cancers

The major types of intraocular cancers which occur in adults are melanoma and lymphoma, and retinoblastoma is a relatively rare cancer in children [109]. The cause of intraocular cancer may vary, and current intraocular cancer treatment includes chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, and surgery [110]. Chemotherapy drugs used to treat ocular cancers include dacarbazine (DTIC), vincristine, etoposide, carboplatin, doxorubicin, and cisplatin. However, chemotherapy incompletely eradicates the tumors because high doses are not delivered to the tumor. The role of an injectable hydrogel in cancer treatments is mainly focused on the localized delivery of chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy drugs. Carboxymethyl Chitosan (CMCS) hydrogels were crosslinked by genipin and studied in terms of the in vitro drug release of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and bevacizumab [27]. The major proportion of 5-FU was released from the drug hydrogels within 8h, but the bevacizumab was released in a slow manner, it was less than 20% after 53h. An in vivo evaluation in rabbits indicated that the drug laden hydrogels were nontoxic and biodegradable.

Chondroitin 6-sulfate (C6S) was incorporated with Poloxamer to form a transparent hydrogel [111]. The copolymer was prepared by EDC crosslinking, and the gelation temperature of the hydrogel was determined to be body temperature, and the gelation temperature could be lowered by decreasing the C6S content and elevating the polymer concentration. The release of drug from the hydrogel was sustained in vitro, and the releasing rate of drug can be altered by the C6S content in the system as the result of the in situ gelation. The C6S-g-Poloxamer-coated surface was observed as biocompatible, suggested from human lens cell (B3) transformed shapes after 2 days. These nanoscale hydrogels may be effective drug carriers for chemotherapy drugs via topical or intraocular administration.

3.10 Other applications

An ophthalmic hydrogel system combined oxidized glutathione (GSSG) with an existing HA using a thiol reaction [24]. This GSSG hydrogel enabled adipose-derived stem cell growth in vitro and biocompatibility of intracutaneous and subconjunctival structures. The hydrogel could also conjugate with other proteins or peptides. Thus, this type of hydrogel could be used for localized ocular drug delivery in the future. Meanwhile, the hydrogel has potential to serve as a 3D scaffold for cell delivery.

An injectable hydrogel can be used as a carrier of iontophoresis nanoparticles [112]. A study with a major focus on the particle distribution into the eye tissue and the penetration efficiency was carried out [113]. Nanoparticles and iontophoresis agents were loaded and injected, and strong fluorescence as a sign of successful delivery was observed as a sign of successful delivery in the anterior and posterior segments. This type of hydrogel provides an alternative approach using the iontophoresis of drug-nanoparticles for ocular treatment.

4 SUMMARY OF CHALLENGE AND PROSPECTIVE

As reviewed above, controlling the synthesis approaches and components can produce hydrogels with desirable properties and functionalities for applications in drug delivery, cell transport, and wound sealing/healing. A summary is presented in Table 2. Naturally derived polymers have advantages over current synthetic polymers, especially in bioactivity and functionality, but batch-to-batch differences of polymers from natural sources may cause instability and inconsistency in therapy, which limits future applications. An injectable hydrogel should be characterized with better-tailored structures, either from bioactive and biofunctional synthetic polymers or well-defined, modified natural polymers, enabling superior performance in drug binding and cell delivery. These materials may become the next generation delivery vehicles in ophthalmic practice.

Table 2.

Summary of the injectable hydrogels in ophthalmic applications

| Disease or Disorder | Hydrogels | Treatment | Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corneal abrasion and Keratoconus | PEG[49] | Doxycycline delivery | Cornea healing, MMP-9 reduced |

| PLGA-PEG-PLGA[50] | Wound healing | High gelation concentration, facilitate cell migration | |

| CHC[51] | Stem cells treatment | Facilitated wound healing | |

| PEG-YRGDS[53] | Regeneration | Improve ECM production | |

| Cataracts | ReSure (I-Zip)[55] | Sealant | Transparent |

| PEG-PVP-PVA[58] | Low swelling, low refractive index | ||

| Tissucol (Fibrin) | Topical use only | ||

| Glaucoma | PNIPAAm-chitosan[31] | Timolol Maleate/Pilocarpine/Kelton delivery | Sustained delivery |

| PNIPAAm-gelatin[64] | Sustained release | ||

| Chitosan-gelatin[26] | Safe in situ crosslinking | ||

| Alginate[35] | Alginate residue have effects | ||

| Chitosan [32] | Latanoprost delivery | Shear reversible | |

| PNIPAM [65] | Epinephrine delivery | Limited release period | |

| Alginate-RGD[67] | Stem cells treatment | Upregulate ganglion cell marker expression | |

| Retinal detachment | Polyacrylamide[69] | Space filling | Transparent and stable |

| PVA[70] | FCVB carrier | Long-term support | |

| PEG-MA[71] | Space filling and retinal support | Inflammation | |

| PEG-MA[72] | Stable | ||

| UV crosslinked HA-[73] | Space filling | Cytotoxicity | |

| Tetra-arm PEG[74] | Non-swelling and stable for 1 year | ||

| Retinitis pigmentosa | Pluronic F-127[33] | Vector delivery | High transduction, but limited biocompatibility |

| PEG-PLL[78] | Stem cells treatment | Potential for retinal ganglion regeneration | |

| DBA-NAS-AA-PNIPAAm[79] | Drug delivery | Stable, slow gelation | |

| Adipic acid-dextran[80] | Must be tested in vivo | ||

| HAMC-HA[83, 84] | Stem cells or RPE cells delivery | High transplantation efficacy, need further study | |

| Collagen-PNIPAAm/HA-PNIPAAm [85, 86] | Improve cell viability, need further study | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | Fibrin-peptides[88] | Heparin-growth factor delivery | Slowed release, regeneration |

| ECM[89] | Facilitate regeneration | ||

| HAMC[84] | Stem cells treatment | Potential for RPC delivery | |

| p(NIPAM-NAC)[91] | |||

| Age-related macular degeneration | PEOX-PCL-PEOX[100] | Anti-VEGF antibody delivery | Prevent worsening of wet AMD |

| ESHU[45] | Retention compared to bolus injection | ||

| Four-arm PEG [101] | Sustained 14 days release | ||

| Alginate[102] | Sustained release, rate related to alginate ratio | ||

| HA-Dextran[103] | Long term release | ||

| Agarose[104] | Light controlled release from AuNP | ||

| Collagen, alginate and chitosan[81, 83]. | RPE and stem cells transplant | Pre- and clinical trial in progress | |

| Inflammation | Hyaluronic acid[107] | Rhodamine-conjugated liposomes delivery | Prolonged release |

| PEG-PCL-PEG[108] | Antibiotics delivery | Problem in IOP and cornea wear | |

| Intraocular cancers | Poloxamer[111] | Chemotherapy | Nanoscale formation |

| CMCS[27] | Extended delivery | ||

| Other | Block copolymers[113] | Ionphoresis | Extend release time |

| GSSG-HA[24] | Stem cells treatment | Early research |

It should be noted that injectable hydrogels have been significantly studied for tissue engineering and cancer treatment [114]. One of the major advantages of the system is its controlled and sustained release properties, which may help prevent toxicity while maximizing the therapeutic index. Indeed, the applications of injectable hydrogels are not limited to the ophthalmic field but also others, such as liver, cartilage, bone, ear, and brain disorders [15–17, 115–117].

Injectable hydrogels have been well-studied as sealants and vitreous humor substitutes, and studies achieved hydrogels with good stability and matching refractive indices. Although proven to be effective as delivery vehicles with improved bioavailability, localized delivery, and cell viability, the use of an injectable hydrogel may not fully overcome the drawback of a therapeutic payload. For instance, intravitreal injection of bevacizumab or other proteinaceous drugs may cause some complications, and the use of hydrogel can enhance the retention time of a therapeutic protein in the eyes. It can reduce the injection frequency and injection-associated complications, but may not completely eliminate side effects. The localized delivery of a targeted drug from an injectable hydrogel may be considered in the future. Furthermore, stem cells from allograft sources may cause several issues, and iPSC from surgery patients may serve as an alternative approach for restoration of human corneal damage. Hydrogels have been demonstrated to enhance the viability of stem cells once encapsulated. The combination of an injectable hydrogel for both localized drug delivery and iPSC therapy is the most promising method for degeneration and inherited disease treatment. Although progress has been made, the massive production and induction for the specific functionality of iPSC still requires further investigation. Moreover, hydrogels can be reservoirs in gene delivery, but the transfection effectiveness still needs improvement compared to virus-based vectors. For ROS-related diseases (AMD and several inflammation), an injectable hydrogel with sustained antioxidant properties and/or payload may become the focus of a treatment study in the coming years. Additionally, although some of the drug delivery and regeneration publications have shown studies in animal models, a large fraction of research using an injectable hydrogel is done at the in vitro level. Only a few studies used ophthalmic study methods (ERG, OCT, Fundus camera, etc.) that fully revealed the functionality of treated or regenerated tissues. Most injectable hydrogel formulations still require further in vivo tests for future clinical application, although perfect animal models for some ophthalmic diseases (e.g. dry AMD) remain challenging to generate.

Last but not least is the issue of FDA approval. Only a limited number of injectable hydrogels are available as FDA-approved commercial products, and most of them are used in the incision healing process in ocular surgery. The clinical use of drug delivery and regeneration hydrogels is under investigation for some types; however, progress is relatively slow and complications remain in stem cell-associated research. It may still take several years to determine clinical outcomes for injectable hydrogels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Eye Institute (R21EY024059 & R01EY026564, Z.H.), the Carolina Center of Nanotechnology Excellence (Z.H.), the UNC Junior Faculty Development Award (Z.H.), and the NC TraCS Translational Research Grant (550KR151611, Z.H.). The authors thank Cassandra Janowski Barnhart, M.P.H. (Department of Ophthalmology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Saaddine JB, Honeycutt AA, Narayan K, Zhang X, Klein R, Boyle JP. Projection of diabetic retinopathy and other major eye diseases among people with diabetes mellitus: United states, 2005–2050. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2008;126:1740–1747. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.12.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2006;90:262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jancevski M, Foster CS. Cataracts and uveitis. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2010;21:10–14. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328332f575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:845–881. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congdon N, O'Colmain B, Klaver CCW, Klein R, Munoz B, Friedman DS, Kempen J, Taylor HR, Mitchell P, Hyman L. G. Eye Dis Prevalence Res, Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012;96:614–618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kholdebarin R, Campbell RJ, Jin Y-P, Buys YM. Multicenter study of compliance and drop administration in glaucoma. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology / Journal Canadien d'Ophtalmologie. 2008;43:454–461. doi: 10.1139/i08-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caprioli J, Coleman AL. Blood Pressure, Perfusion Pressure, and Glaucoma. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;149:704–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han Z, Banworth MJ, Makkia R, Conley SM, Al-Ubaidi MR, Cooper MJ, Naash MI. Genomic DNA nanoparticles rescue rhodopsin-associated retinitis pigmentosa phenotype. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2015;29:2535–2544. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-270363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng M, Mitra RN, Filonov NA, Han Z. Nanoparticle-mediated rhodopsin cDNA but not intron-containing DNA delivery causes transgene silencing in a rhodopsin knockout model. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2016;30:1076–1086. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-280511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett J, Wellman J, Marshall KA, McCague S, Ashtari M, DiStefano-Pappas J, Elci OU, Chung DC, Sun J, Wright JF, Cross DR, Aravand P, Cyckowski LL, Bennicelli JL, Mingozzi F, Auricchio A, Pierce EA, Ruggiero J, Leroy BP, Simonelli F, High KA, Maguire AM. Safety and durability of effect of contralateral-eye administration of AAV2 gene therapy in patients with childhood-onset blindness caused by RPE65 mutations: a follow-on phase 1 trial. The Lancet. 388:661–672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misra GP, Gardner TW, Lowe TL. Hydrogels for Ocular Posterior Segment Drug Delivery. In: Kompella BU, Edelhauser FH, editors. Drug Product Development for the Back of the Eye. Springer US; Boston, MA: 2011. pp. 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fathi M, Barar J, Aghanejad A, Omidi Y. Hydrogels for ocular drug delivery and tissue engineering. BioImpacts : BI. 2015;5:159–164. doi: 10.15171/bi.2015.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitra RN, Zheng M, Han Z. Nanoparticle-motivated gene delivery for ophthalmic application. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2016;8:160–174. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overstreet DJ, Dutta D, Stabenfeldt SE, Vernon BL. Injectable hydrogels. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics. 2012;50:881–903. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Rodrigues J, Tomas H. Injectable and biodegradable hydrogels: gelation, biodegradation and biomedical applications. Chemical Society Reviews. 2012;41:2193–2221. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15203c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J-A, Yeom J, Hwang BW, Hoffman AS, Hahn SK. In situ-forming injectable hydrogels for regenerative medicine. Progress in Polymer Science. 2014;39:1973–1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annabi N, Tamayol A, Uquillas JA, Akbari M, Bertassoni LE, Cha C, Camci-Unal G, Dokmeci MR, Peppas NA, Khademhosseini A. 25th Anniversary Article: Rational Design and Applications of Hydrogels in Regenerative Medicine. Advanced Materials. 2014;26:85–124. doi: 10.1002/adma.201303233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen MK, Alsberg E. Bioactive factor delivery strategies from engineered polymer hydrogels for therapeutic medicine. Progress in Polymer Science. 2014;39:1235–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang K, Buschle-Diller G, Misra RDK. Chitosan-based injectable hydrogels for biomedical applications. Materials Technology. 2015;30:B198–B205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Vlierberghe S, Dubruel P, Schacht E. Biopolymer-Based Hydrogels As Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:1387–1408. doi: 10.1021/bm200083n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mawad D, Anne Boughton E, Boughton P, Lauto A. Advances in hydrogels applied to degenerative diseases. Current pharmaceutical design. 2012;18:2558–2575. doi: 10.2174/138161212800492895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarembinski TI, Doty NJ, Erickson IE, Srinivas R, Wirostko BM, Tew WP. Thiolated hyaluronan-based hydrogels crosslinked using oxidized glutathione: An injectable matrix designed for ophthalmic applications. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchhof S, Goepferich AM, Brandl FP. Hydrogels in ophthalmic applications. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2015;95:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muzzarelli RA. Genipin-crosslinked chitosan hydrogels as biomedical and pharmaceutical aids. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2009;77:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L-q, Lan Y-q, Guo H, Cheng L-z, Fan J-z, Cai X, Zhang L-m, Chen R-f, Zhou H-s. Ophthalmic drug-loaded N, O-carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogels: synthesis, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2010;31:1625–1634. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ulijn RV, Bibi N, Jayawarna V, Thornton PD, Todd SJ, Mart RJ, Smith AM, Gough JE. Bioresponsive hydrogels. Materials today. 2007;10:40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2010;62:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattarai N, Ramay HR, Gunn J, Matsen FA, Zhang M. PEG-grafted chitosan as an injectable thermosensitive hydrogel for sustained protein release. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;103:609–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Y, Zhang C, Shen W, Cheng Z, Yu L, Ping Q. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)–chitosan as thermosensitive in situ gel-forming system for ocular drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;120:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsiao M-H, Chiou S-H, Larsson M, Hung K-H, Wang Y-L, Liu CJ-L, Liu D-M. A temperature-induced and shear-reversible assembly of latanoprost-loaded amphiphilic chitosan colloids: Characterization and in vivo glaucoma treatment. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:3188–3196. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strappe PM, Hampton DW, Cachon-Gonzalez B, Fawcett JW, Lever A. Delivery of a lentiviral vector in a Pluronic F127 gel to cells of the central nervous system. European journal of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics. 2005;61(3):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibata H, Heo YJ, Okitsu T, Matsunaga Y, Kawanishi T, Takeuchi S. Injectable hydrogel microbeads for fluorescence-based in vivo continuous glucose monitoring. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:17894–17898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006911107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Liu J, Zhang X, Zhang R, Huang Y, Wu C. In situ gelling gelrite/alginate formulations as vehicles for ophthalmic drug delivery. Aaps PharmSciTech. 2010;11:610–620. doi: 10.1208/s12249-010-9413-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sultana Y, Aqil M, Ali A. Ion-activated, Gelrite®-based in situ ophthalmic gels of pefloxacin mesylate: comparison with conventional eye drops. Drug Delivery. 2006;13:215–219. doi: 10.1080/10717540500309164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang K, Nune KC, Misra RDK. The functional response of alginate-gelatin-nanocrystalline cellulose injectable hydrogels toward delivery of cells and bioactive molecules. Acta Biomaterialia. 2016;36:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peak CW, Wilker JJ, Schmidt G. A review on tough and sticky hydrogels. Colloid and Polymer Science. 2013;291:2031–2047. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: Progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49:1993–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin C-C, Metters AT. Hydrogels in controlled release formulations: Network design and mathematical modeling. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2006;58:1379–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang K, David AE, Choi Y-S, Wu Y, Buschle-Diller G. Scaffold materials from glycosylated and PEGylated bovine serum albumin. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2015;103:2839–2846. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Advanced Materials. 2006;18:1345–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwon JW, Han YK, Lee WJ, Cho CS, Paik SJ, Cho DI, Lee JH, Wee WR. Biocompatibility of poloxamer hydrogel as an injectable intraocular lens: a pilot study. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 2005;31:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai J-Y. Biocompatibility of chemically cross-linked gelatin hydrogels for ophthalmic use. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine. 2010;21:1899–1911. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rauck BM, Friberg TR, Mendez CAM, Park D, Shah V, Bilonick RA, Wang Y. Biocompatible Reverse Thermal Gel Sustains the Release of Intravitreal Bevacizumab In Vivo. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;55:469–476. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose JB, Pacelli S, Haj AJE, Dua HS, Hopkinson A, White LJ, Rose FR. Gelatin-based materials in ocular tissue engineering. Materials. 2014;7:3106–3135. doi: 10.3390/ma7043106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-A-induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2003;135:620–627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xinming L, Yingde C, Lloyd AW, Mikhalovsky SV, Sandeman SR, Howel CA, Liewen L. Polymeric hydrogels for novel contact lens-based ophthalmic drug delivery systems: a review. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye. 2008;31:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anumolu SS, DeSantis AS, Menjoge AR, Hahn RA, Beloni JA, Gordon MK, Sinko PJ. Doxycycline loaded poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogels for healing vesicant-induced ocular wounds. Biomaterials. 2010;31:964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pratoomsoot C, Tanioka H, Hori K, Kawasaki S, Kinoshita S, Tighe PJ, Dua H, Shakesheff KM, Rose FRAJ. A thermoreversible hydrogel as a biosynthetic bandage for corneal wound repair. Biomaterials. 2008;29:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chien Y, Liao Y-W, Liu D-M, Lin H-L, Chen S-J, Chen H-L, Peng C-H, Liang C-M, Mou C-Y, Chiou S-H. Corneal repair by human corneal keratocyte-reprogrammed iPSCs and amphiphatic carboxymethyl-hexanoyl chitosan hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2012;33:8003–8016. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gomes JAP, Monteiro BG, Melo GB, Smith RL, da Silva MCP, Lizier NF, Kerkis A, Cerruti H, Kerkis I. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of human immature dental pulp stem cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2010;51:1408–1414. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]