Abstract

Socioeconomic factors are known to be contributing factors for vehicle-pedestrian crashes. Although several studies have examined the socioeconomic factors related to the location of the crashes, limited studies have considered the socioeconomic factors of the neighborhood where the road users live in vehicle-pedestrian crash modelling. This research aims to identify the socioeconomic factors related to both the neighborhoods where the road users live and where crashes occur that have an influence on vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. Data on vehicle-pedestrian crashes that occurred at mid-blocks in Melbourne, Australia, was analyzed. Neighborhood factors associated with road users’ residents and location of crash were investigated using boosted regression tree (BRT). Furthermore, partial dependence plots were applied to illustrate the interactions between these factors. We found that socioeconomic factors accounted for 60% of the 20 top contributing factors to vehicle-pedestrian crashes. This research reveals that socioeconomic factors of the neighborhoods where the road users live and where the crashes occur are important in determining the severity of the crashes, with the former having a greater influence. Hence, road safety countermeasures, especially those focussing on the road users, should be targeted at these high-risk neighborhoods.

Keywords: Vehicle-pedestrian crashes, Boosted regression tree, Neighborhood socioeconomic influences, Neighborhoods where road users live, Neighborhood where crash occur

Introduction

Pedestrians are known as vulnerable road users due to their lack of protection and are thus more likely to be killed or seriously harmed in vehicle-pedestrian crashes. For example, pedestrians are 23 times more likely to be killed in vehicle-pedestrian crashes than car occupants in the USA [1]. According to the World Health Organisation [2], 22% of the 1.25 million people killed each year in road traffic crashes worldwide are pedestrians. In Calgary, Canada, only 7.4% of the vehicle-vehicle collisions on local roads resulted in injuries [3], but 84.8% of the pedestrian-vehicle collisions on local roads resulted in deaths or serious injuries [4]. In Great Britain, 23% of all fatalities in road crashes in 2013 were pedestrians [5] and 39% of the traffic fatalities in Korea were pedestrians [6]. Likewise, 4884 pedestrians were killed in the USA and an estimated 65,000 were injured in traffic crashes in 2014 [7].

Therefore, vehicle-pedestrian crashes are a major concern in many countries, and many studies have been conducted to identify the factors contributing to these crashes. Personal characteristics of pedestrian, such as age and gender, have been found to be significant variables in several studies [6, 8–10], while vehicle type and road geometry factors have been identified as important variables in other studies [11–13]. Additionally, the influences of built environment, environment condition, and speed limit have also been investigated in many studies [14–17].

Relatively few studies, however, had examined the contribution of socioeconomic factors, such as culture, income and level of education, on vehicle-pedestrian crashes. Campos-Outcalt et al. [18] examined the influence of race and ethnicity on pedestrian crashes in Arizona and revealed that the rates and circumstances of pedestrian deaths were affected by these factors. In addition, several studies had examined the influences of income and education level on vehicle-pedestrian crashes [19–22].

In general, two main approaches were used to examine the influence of socioeconomic variables on vehicle-pedestrian crashes. Some studies used the socioeconomic characteristics of the neighborhood where pedestrians lived [19, 21, 22] while other studies used the socioeconomic factors related to the neighborhoods where the crash occurred [23, 24]. However, limited or no study has investigated the socioeconomic factors related to both types of neighborhoods or examined their relative importance.

Studies show that social and economic factors related to location of crashes could influence on vehicle-pedestrian severity level (Table 1). For instance, Wier et al. [25] and Graham et al. [26] showed that the proportion of low-income households and the proportion of people without access to a motor vehicle were contributing factors for vehicle-pedestrian crash injury severity. Therefore, understanding the social and economic factors related to location of crashes may assist road safety professionals to target suburbs to apply site-specific pedestrian safety programs and improving vehicle-pedestrian safety issue in these suburbs.

Table 1.

Distribution of categorical variables

| Factors | Severity | Factors | Severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal | Serious injury | Other injury | Fatal | Serious injury | Other injury | ||||

| Season | Fall | 5.6% | 49.4% | 44.9% | Vehicle type | Bus | 0 | 55.6% | 44.4% |

| Spring | 5.0% | 53.3% | 41.7% | Heavy vehicles | 27.3% | 27.3% | 45.5% | ||

| Summer | 5.3% | 49.9% | 44.8% | Motor and bike | 2.5% | 54.3% | 43.2% | ||

| Winter | 6.3% | 48.6% | 45.1% | Other | 22.4% | 46.9% | 30.6% | ||

| Time of Crash | 1Peak (7:00–9:00) | 4.7% | 40.4% | 54.9% | Passenger car | 5.2% | 51.2% | 43.6% | |

| 2Peak (16:00–19:00) | 15.8% | 61.8% | 22.4% | Taxi and van | 4.9% | 39.9% | 55.2% | ||

| Off-Peak (9:00–16:00) | 3.1% | 46.4% | 50.4% | Tram and train | 7.1% | 51.8% | 41.1% | ||

| Other | 6.8% | 55.1% | 38.1% | Traffic condition | Flash | 3.4% | 50.4% | 46.2% | |

| Day of Crash | Weekdays | 5.1% | 48.7% | 46.2% | No control | 5.7% | 51.0% | 43.3% | |

| Weekend | 7.0% | 55.2% | 37.8% | Pedestrian crossing | 5.4% | 48.6% | 45.9% | ||

| Pedestrian Age | 19–24 | 3.2% | 52.0% | 44.8% | Pedestrian light | 6.6% | 50.0% | 43.4% | |

| 25–44 | 5.5% | 51.6% | 42.9% | School crossing | 16.7% | 16.7% | 66.7% | ||

| 45–64 | 4.9% | 47.7% | 47.4% | Unknown | 4.3% | 42.7% | 53.0% | ||

| 65–74 | 9.3% | 47.5% | 43.2% | Surface condition | Dry | 5.3% | 49.7% | 45.0% | |

| 75+ | 13.0% | 51.6% | 35.3% | Icy | 0 | 100.0% | 0 | ||

| Other | 50.0% | 50.0% | Other | 3.4% | 25.4% | 71.2% | |||

| Under 18 | 2.1% | 49.5% | 48.3% | Wet | 7.8% | 59.3% | 32.9% | ||

| Pedestrian Gender | Female | 3.6% | 47.8% | 48.5% | Atmosphere condition | Clear | 5.7% | 50.0% | 44.3% |

| Male | 7.1% | 52.0% | 40.9% | Dust | 0 | 0 | 100.0% | ||

| Unknown | 66.7% | 33.3% | Fog | 0 | 66.7% | 33.3% | |||

| Driver Age | 26–44 | 5.4% | 49.1% | 45.6% | Raining | 5.4% | 62.3% | 32.3% | |

| 45–64 | 4.8% | 48.4% | 46.8% | Strong wind | 0 | 50.0% | 50.0% | ||

| 65–74 | 5.0% | 54.5% | 40.6% | Unknown | 3.2% | 23.8% | 73.0% | ||

| 75+ | 6.6% | 48.7% | 44.7% | Light condition | Dark light on | 9.4% | 60.0% | 30.6% | |

| Other | 9.1% | 63.6% | 27.3% | Dark no light | 20.0% | 48.2% | 31.8% | ||

| Under 25 | 6.9% | 53.8% | 39.2% | Day | 3.2% | 46.1% | 50.8% | ||

| Driver Gender | Female | 4.2% | 49.8% | 46.0% | Dusk/dawn | 4.9% | 52.9% | 42.2% | |

| Male | 6.3% | 50.6% | 43.2% | Other | 0 | 54.5% | 45.5% | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 25.0% | 75.0% | Speed limit | < 60 | 1.1% | 44.0% | 54.9% | |

| Pedestrian Gender | Female | 3.6% | 47.8% | 48.5% | > 70 | 16.4% | 58.9% | 24.6% | |

| Male | 7.1% | 52.0% | 40.9% | 60–70 | 6.1% | 53.2% | 40.7% | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 66.7% | 33.3% | Other | 1.0% | 33.7% | 65.4% | ||

| Land Use | Commercial | 3.3% | 45.2% | 51.5% | Road dividing type | Divided double line (DD) | 12.8% | 54.4% | 32.8% |

| Community and Education | 3.7% | 61.1% | 35.2% | Divided single centerline representation (DS) | 6.3% | 53.7% | 40.0% | ||

| Industrial | 10.7% | 52.7% | 36.7% | Not divided (ND) | 4.2% | 49.1% | 46.7% | ||

| Residential | 5.2% | 55.5% | 39.3% | Unknown (U) | 3.8% | 46.8% | 49.4% | ||

| Sport and recreation | 8.3% | 46.9% | 44.8% | Existence of road median | Yes | 5.5% | 50.2% | 44.3% | |

| Undefined | 6.2% | 49.9% | 43.9% | No | 1.0% | 40.0% | 59.0% | ||

Meanwhile, other studies showed that socio-economic factors could influence road users’ behavior [27, 28]. For instance, studies showed that ethnicity and family background were important factors associated with traffic crashes [29–31]. Therefore, using drivers’ and pedestrians’ residency neighborhood social and economic factors can assist in identifying target suburbs to apply different road user behavior change programs and improve traffic safety knowledge of road users in these suburbs.

This research aims to examine the influence of socioeconomic factors of the neighborhoods where the crashes occur, the neighborhoods where drivers live and the neighborhoods where pedestrians live, as well as examining their relative importance. It will examine the neighborhoods where the road users live (residency neighborhood) and where the crashes occur (crash neighborhood) on vehicle-pedestrian crash severity, while controlling for the influences of roadway, road user, vehicle and environmental factors. It will contribute to advancing knowledge in the field as very limited research has been conducted to examine the influence of socioeconomic factors of both the neighborhoods where the crashes occur and where the pedestrians live.

Data

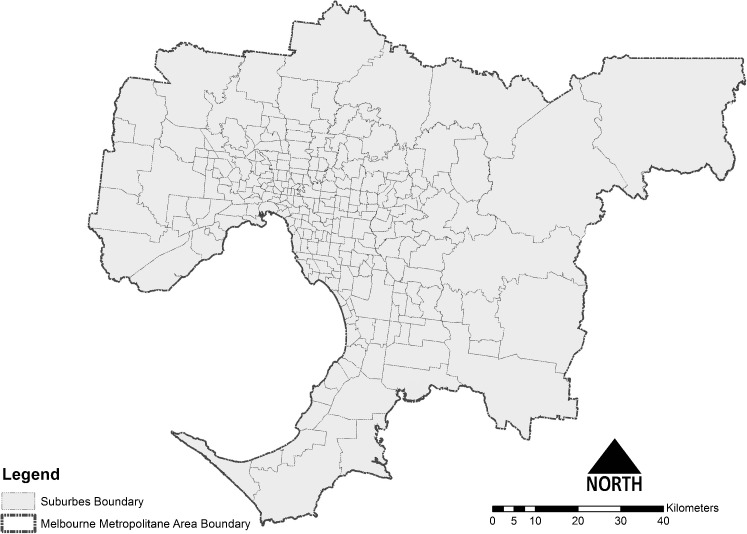

Data on vehicle-pedestrian crashes on public roads that occurred at mid-blocks in the Melbourne metropolitan area from 2004 to 2013 were extracted from Victoria Road Crash Information database. Melbourne metropolitan area refers to Capital City Statistical Division (Capital City SDs) in Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) [32]. According to ASGC definition, Capital City SDs are predominantly urban in character and represent the state/territory capital cities in the wider sense. Figure 1 shows the Melbourne metropolitan area. It should be noted that in Victoria, Australia, only crashes resulting in deaths or injuries were required to be reported to the police. In this database, the severity of a crash was determined by the person who suffered the most severe injury and was recorded using three categories. A fatal crash referred to a crash in which at least one person died within 30 days of a collision. According to VicRoads classification, a serious injury crash referred to a collision that resulted in at least one person being sent to hospital. Other injury crash referred to a crash that did not have any fatality or serious injury.

Fig. 1.

Melbourne metropolitan area and its suburbs

Data on the socioeconomic factors were extracted from Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Since information on the postcodes of the crash location and the addresses of the persons involved in the crash (residency location) were available in the crash database, socioeconomic data at the postcode level were extracted from the ABS. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) was then used to merge the crash information and the socioeconomic data. The final dataset used contained 3577 crashes, of which 152 (4%) were fatal crashes, 1679 (47%) were serious injury crashes and 1746 (49%) were other injury crashes. It should be noted that 20% of pedestrian, 11% of drivers and only 6% of both drivers and pedestrians had the same postcode for the crash location and residency locations. Table 1 and 2 show the summary of categorical and continuous variables used in this research.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for continuous variables

| Factors | Unit | Mean | Std. Deviation | Factors | Unit | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic and geometry | Traffic volume | Vehicles per day | 13,376.63 | 10,201.44 | Social and economical | Secondary and under | Percent | 16.55 | 7.26 |

| Average slope | Percent | 1.37 | 3.01 | Technical or further educational | Percent | 7.29 | 1.88 | ||

| Distance to public transport station | Meter | 137.73 | 422.62 | University or other tertiary institution | Percent | 23.35 | 14.39 | ||

| Road width | Meter | 20.03 | 10.93 | Other type education | Percent | 28.67 | 10.33 | ||

| Social and economical | Population density | pop per Sq. Kilometres | 2794.43 | 2058.17 | Employed rate | Percent | 93.70 | 2.80 | |

| Indigenous | Percent | .40 | .30 | Labour force participants | Percent | 61.36 | 7.17 | ||

| Median age | Percent | 35.53 | 4.85 | White collar job | Percent | 20.45 | 5.97 | ||

| Median Income | Percent | 635.99 | 192.92 | Blue collar job | Percent | 21.80 | 9.03 | ||

| Born in Australia | Percent | 57.07 | 15.30 | Pink collar job | Percent | 57.46 | 5.29 | ||

| Born UK | Percent | 3.83 | 1.96 | Use train to commute | Percent | 6.61 | 4.20 | ||

| Born in Asia | Percent | 12.45 | 11.01 | Use bus to commute | Percent | 1.41 | 1.32 | ||

| Born in India | Percent | 3.01 | 2.29 | Use tram to commute | Percent | 5.16 | 7.12 | ||

| Born in Middle East | Percent | .59 | 1.64 | Use other type to commute | Percent | 3.98 | 2.70 | ||

| Born in South eastern of Europe | Percent | 2.39 | 2.24 | Use private car to commute | Percent | 55.63 | 18.11 | ||

| Born in other | Percent | 13.66 | 4.17 | Use walk to commute | Percent | 7.45 | 11.53 | ||

| Born location Not sated | Percent | 6.99 | 4.38 | ||||||

Method

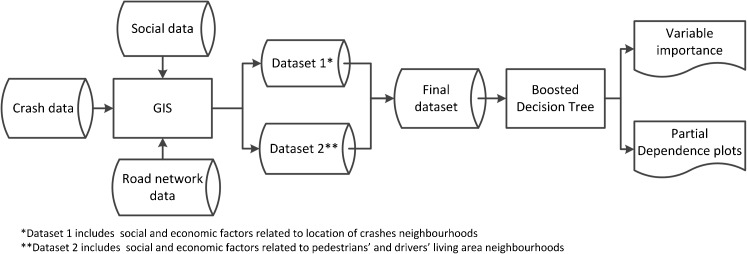

GIS is applied in this research to compile the dataset. All data including crash data, social and economic data and traffic data are added as separate layers in Arcmap GIS and merges using the postcodes of the crash locations and the postcodes of the road users’ addresses to their. The final dataset includes traffic and road characteristics data, personal characteristics data and socioeconomic data for location of crashes and road users’ residency neighborhood. Then, this final dataset is applied in boosted decision tree (BDT) to identify contributing factors for vehicle-pedestrian crashes. Figure 2 shows the method that is applied in this research.

Fig. 2.

Methodology that is applied in this research

Non-parametric techniques such as decision tree (DT) and support vector machine have been used in different traffic crash severity analysis [33–38]. The DT approach is a simple and powerful method to solve classification problems and provides a graphical structure using a tree with many branches and leaves. These graphical features are useful in understanding and interpreting the results [34].

In DT models, the root node in top of tree which contains all objects is split into two homogeneous sets that are called child nodes. Then, DT splits child nodes until no further split can be made, i.e. all child nodes are homogenous (or a user-defined minimum number of objects in the node is reached). These final nodes are called terminal nodes or leaves and they have no branches. DT then removes all branches with little impact on the predictive value of the tree. In the DT technique, the best tree is determined by dividing the sample into learning and test sub-samples and the testing error rates or costs are used to prune the tree. The learning sample is used to grow an overly large tree. Then, the test sample is used to estimate the rate at which cases are misclassified (possibly adjusted by misclassification costs). The misclassification error rate is calculated for the largest tree and also for every sub-tree. The best sub-tree is the one with the lowest or near-lowest cost, which may be a relatively small tree.

One disadvantage of the DT model is that it is often unstable, and the results may change significantly with changes in the training and testing the data [39]. Therefore, ensemble models, such as bagged decision tree (BgDT), boosted decision tree (BDT) and random forest (RF), are applied in some studies to improve the reliability and accuracy of DT models [24, 40–44]. Since BDT has better performance in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity analysis than DT and BgDT models [24], BDT model is applied in this research to explore the factors contributing to vehicle-pedestrian crash severity.

BDT combines regression trees and boosting technique to improve the performance of DT models. Boosting is a forward and stage-wise procedure in which a subset of data is randomly selected to iteratively produce new tree models to improve the quality of prediction [45]. This process introduces a stochastic gradient boosting procedure that can improve model performance and reduce the risk of over-fitting [46]. In stochastic gradient boosting procedure, at each iteration, a subsample of the training data is drawn at random (without replacement) from the full training dataset. The randomly selected subsample is then used, instead of the full sample, to fit the base learner.

In this approach, after the first tree is fitted, the residuals are calculated. In BDT, the difference between the target function and the current predictions of an ensemble is called the residual. In next step, observations with high residual values are defined as an observation with high prediction error. Then, BDT calculates the adjustment weights using Eq. 1:

| 1 |

where 0 ≤ m(i) ≤ n and n is the number of fitted decision tree models and m is the number of models that misclassified cases i in the previous step. The weights are then used to adjust the estimated probabilities and minimize the misclassification error rate. Hence, subsequent trees are fitted to the residual of the previous tree [47]. This process is repeated n times and m models to adjust the estimated probabilities.

In DT model, the relative importance of the independent variables (predictors) is calculated based on the number of times a variable is selected to split a node and the improvements in classification. However, in the BDT model, the importance of a predictor x i for a classifier Γ is obtained by averaging or weighted averaging the importance in the set of classifiers (dependent variables) using Eq. 2 [48].

| 2 |

where C is the number of classifiers in the BDTs and Tc indicates the decision tree produced at the cth step.

In this research, fitted BDT models were obtained using the “gbm” library [49] in the R software [50] in the caret package [51]. To develop the BDT model, the repeated k-fold cross-validation technique was applied. The dataset was randomly divided into k blocks of roughly equal size instead of dividing the data into training and testing sub-sets. In each iteration, one block was left out and the other k-1 blocks were used to train the model. Each k block was left out once and the left out block was used for prediction. These predictions are summarized in a performance measure (e.g. accuracy). This procedure was repeated s times to decrease the error and find the most robust model. The (s x k) estimates of performance were then averaged to obtain the overall re-sampled estimate.

In this research, a 10-fold cross-validation with 5 iterations [24] was applied for each model, and the performances of the models were estimated. In addition to the error rate, interaction depth and shrinkage were other parameters that were used to evaluate the BDT models. The shrinkage or learning rate was used to determine the contribution of each tree to the growing model. This parameter was used to decrease the contribution of each tree in the model. Tree complexity or interaction depth represented the depth of a tree and showed the interaction among predictor variables. Based on previous research, the interaction depth and shrinkage parameters were assumed to be 15 and 0.1 [24], respectively, in this study and the model repeated 2000 times (boosting iterations) to find the final model.

Results and Discussion

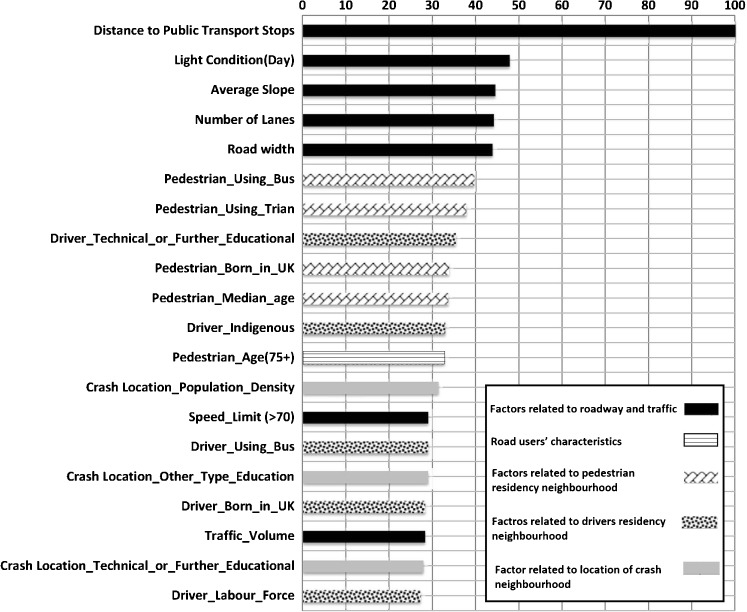

Identifying factors that might have important relationships with vehicle-pedestrian crash severity could assist traffic safety professionals in choosing the appropriate safety countermeasures, such as road geometry modifications, improving traffic safety knowledge or changing road user behaviors through social marketing campaigns. The top 20 factors identified by the BDT models are shown in Fig. 3. To facilitate comparison, the score indicating the importance of each factor was scaled so that the top factor has a score of 100. In general, the top 20 most important factors could be grouped into five categories: roadway and traffic, road user characteristics, drivers’ residency neighborhood, pedestrians’ residency neighborhood and crash neighborhood factors. In addition to the importance plot, the partial dependence plot for these factors was also generated and shown in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 to facilitate the interpretation of the results.

Fig. 3.

20 top relative important variables in BDT model for vehicle-pedestrian crashes

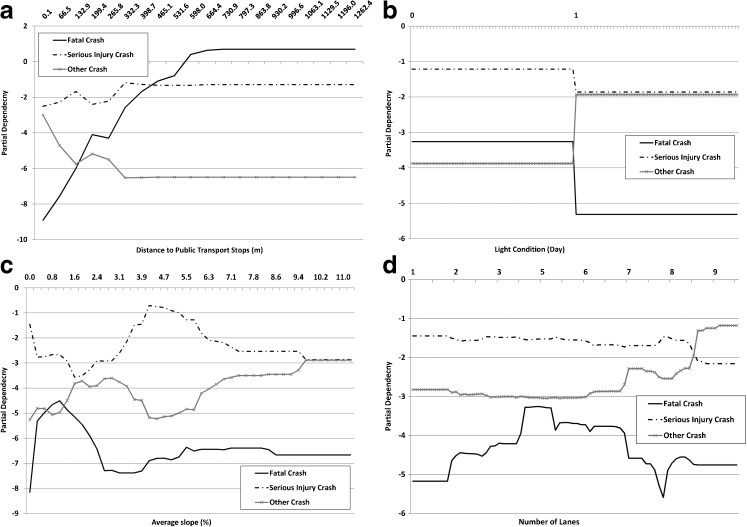

Fig. 4.

Roadway and traffic-related factors. a Distance from public transport stops. b Light condition. c Road gradient. d Number of lanes

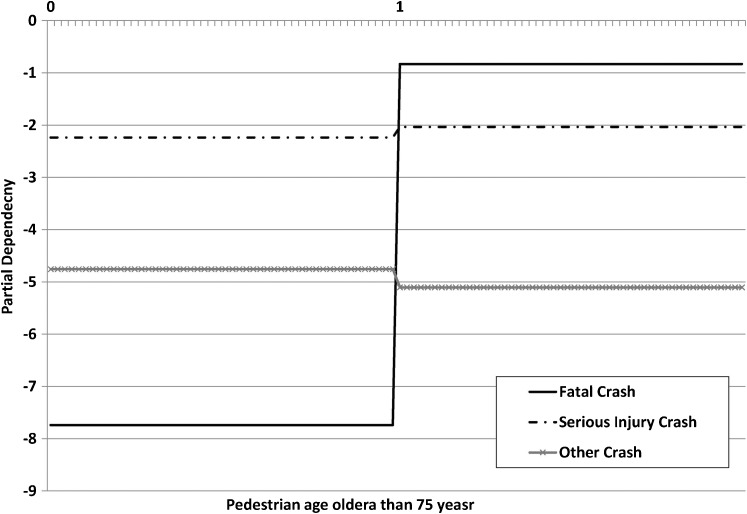

Fig. 5.

Road users’ characteristics (population over 75 years of age)

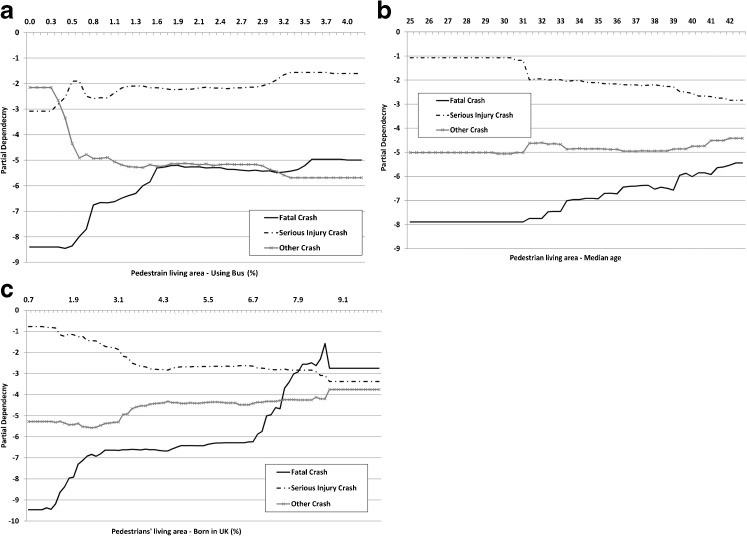

Fig. 6.

Pedestrian residency neighborhood factors. a Bus commutes. b Suburbs median age. c Born in UK

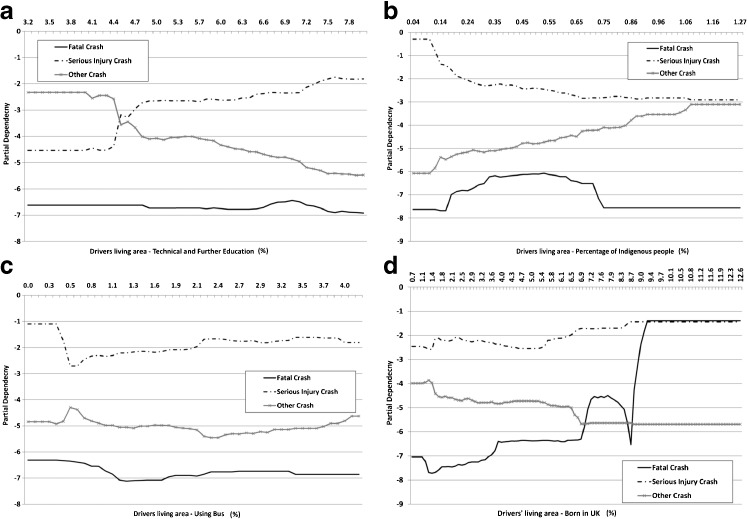

Fig. 7.

Drivers residency neighbourhood factors. a Tertiary education. b Indigenous people. c Bus commutes. d Born in UK

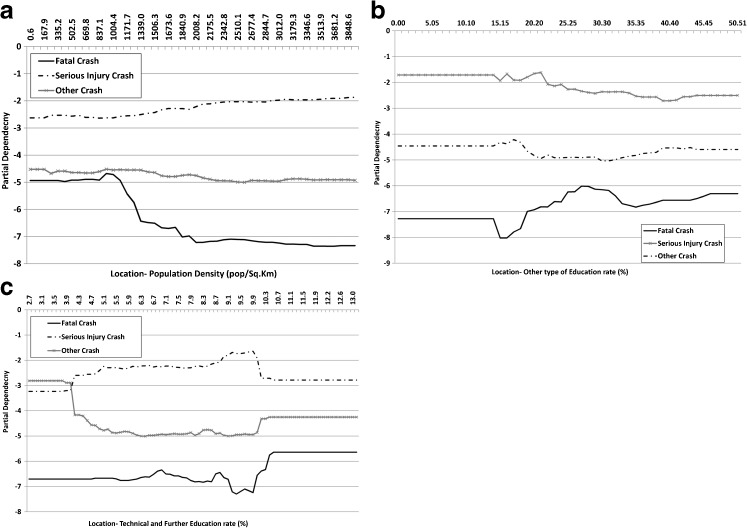

Fig. 8.

Crash neighborhood factors. a Population density. b Other type of education. c Tertiary education

As shown in Fig. 3, seven of the top 20 factors were roadway and traffic-related factors, one was related to the characteristics of road users involved in the crash, four were socioeconomic factors of the pedestrians’ residency neighborhood, five were related to drivers’ residency neighborhood and three were related to the socioeconomic characteristics of the crash location. Also, six of the socioeconomic characteristics of the drivers’ and pedestrians’ residency neighborhoods were ranked ahead all the socioeconomic factors related to the crash location. These findings implied that the socioeconomic factors related to drivers’ and pedestrian’ residency neighborhoods were more important than the socioeconomic factors related to the locations of crashes.

Roadway and Traffic-Related Factors

According to Fig. 3, seven of the top 20 factors were roadway and traffic-related factors, and five of them were ranked at the top. Overall, the most important contributing factor identified by the BDT model was distance of vehicle-pedestrian crash locations to public transport stops. Also, as shown in Fig. 4a, an increase in the distance between the crash location and public transport stop up to 600 m was associated with an increase in the probability of a crash being severe (fatal or seriously injury). This finding was similar to the results of other published research [24]. Therefore, applying lower speed limits around public transport stops or using on-site safety posters or signs to warn drivers and pedestrians to be more careful might assist in reducing vehicle-pedestrian crash severity in these areas. Additionally, the existence of buses in bus stops could decrease the drivers’ and pedestrians’ sight distances and increase the probability of crashes. Designing proper bus stop bays might help to resolve this problem and reduce the risk and the severity of vehicle-pedestrian crashes.

As shown in Fig. 3, the next four most important factors in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity were also related to roadway and traffic factors, including light condition, road gradient, number of lanes and road width. These findings were consistent with published research [10, 52–55]. According to Fig. 4b, the risks of fatal and serious injuries in vehicle-pedestrian crashes were lower in day-time than at night. This finding is expected because an increase in lighting and visibility would increase sight distance. Hence, installing street lighting in vehicle-pedestrian crash hotspots would alleviate this safety issue.

In addition, according to Fig. 4c, increasing the road slope up to about 1% would increase the likelihood of the crash being fatal, while the risk of serious injury would increase between 1 and 4% road slope, and further increases in road slope would increase likelihood of the crash resulting in only minor injury. Road gradient could impact the breaking distance and driver sight distance. Therefore, applying lower speed limit on roads with slope and providing sufficient advance warning to drivers to reduce their vehicle speed could reduce the vehicle-pedestrian crash severity.

Furthermore, according to Fig. 4d, increasing the number of lanes and road width would increase the severity of vehicle-pedestrian crashes. On wider roads, pedestrians would need more time to cross the roads, and thus installing pedestrian crossing facilities and road medians on wider roads to provide a safe refuge when crossing the roads could be an effective means to improve pedestrian safety (Table 2).

Road Users’ Characteristics

Four road users’ characteristics were examined in this study because these were the only characteristics for which data were available. These characteristics included the age (six groups) and gender (three groups) of the drivers, and the age (seven groups) and gender (three groups) of the pedestrians involved in the crashes. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 3, only one of these 19 variables was ranked in the top 20 contributing factors. Driver gender (male), for example, had an importance score of only 2.4 and was not ranked in the top 100 variables. Among other reasons, the age and gender of road users were often used to capture their attitudes and behaviors, and these characteristics were found to be significant in many studies [4, 6, 56]. However, part of these influences might have been captured by the socioeconomic characteristics of the drivers’ and pedestrians’ residency neighborhoods.

Pedestrians aged 75 and older were the only variable to be ranked in the top 20 factors affecting vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. Also, according to Fig. 5, pedestrians over 75 years of age experienced an increase in the risk of suffering a fatal or serious injury in a vehicle-pedestrian collision. This result was expected because of the increased fragility of older pedestrians. This result was similar to results of other studies showing that an increase in the age of the pedestrians would increase the probability of serious and fatal crashes [9, 52, 57].

Pedestrians’ Residency Neighborhood Characteristics

As shown in Fig. 6a, variations in the percentage of public transport usage for commuting in pedestrians’ residency neighborhood would have a considerable influence on the vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. According to the figure, increases in the percentage of public transport usage in pedestrians’ residency neighborhood were associated with increases in the probability of fatal and serious injury crashes, although the risk of fatal injury appeared to plateau around 1.5%. Moreover, as discussed previously, the probability of a crash to be serious or fatal would increase with increasing distance from public transport stops. These results were expected because people need to walk to access to public transport stops, and pedestrians would often jaywalk to catch the bus or tram. Therefore, the probability of a vehicle-pedestrian crash being severe would be higher for pedestrians who lived in suburbs with high percentages of bus usage.

As shown in Fig. 3, the median age of people living in the pedestrians’ residency neighborhood was an important contributing factor in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 6b, the probability of a vehicle-pedestrian crash to result in fatality or serious injury would be higher for pedestrians who lived in suburbs with a higher median age than 30 years of age, and this risk would increase with increasing median age. Therefore, pedestrian-related road safety campaigns or health promotion activities should be targeted at these suburbs.

According to Fig. 3, country of birth would be another contributing factor in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. People from different family background and culture would have different attitudes and walking behaviours, which could have an impact on vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. Previous research had shown that ethnicity and family background were important factors associated with traffic crashes [29–31]. Our results, as highlighted in Fig. 6c, suggested that suburbs with higher proportions of people born in the UK could be targeted for pedestrian safety educational programs or campaigns. These programs could increase the traffic safety knowledge, especially safe walking knowledge, and improve pedestrian safety for people living in these targeted suburbs.

Drivers’ Residency Neighborhood Characteristics

As shown in Fig. 3, the level of education in the drivers’ residency neighborhoods was an important contributing factor in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. According to Fig. 7a, an increase in the number of people with technical and further education in the drivers’ residency neighborhoods would increase the risk of a serious injury crash instead of a minor injury crash. This result was consistent with previous studies that found that drivers with higher levels of education accepted more risk in driving and were more involved in traffic crashes [58, 59]. Therefore, driver safety education, pedestrian awareness campaigns and other behavioral change programs should be targeted at neighborhoods with higher proportions of people with technical education.

As shown in Fig. 3, the ethnicity of the people living in the drivers’ residency neighborhoods was an important contributing factor in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. According to Fig. 7b, increases in the percentage of people living the drivers’ residency neighborhoods with indigenous background from 0.2 to 0.6 would increase the probability of vehicle-pedestrian crashes to be fatal but decrease the probability of vehicle-pedestrian crashes resulting in serious injuries.

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3, the percentage of public transport use in drivers’ residency neighborhoods could influence the severity of vehicle-pedestrian crashes. Also, according Fig. 7c, that the severity of crash would generally be lower in suburbs where more people use public transport. Drivers living in these suburbs might be more aware of and had better attitudes towards pedestrians and public transport users. Therefore, education programs and campaigns to inform drivers about pedestrian safety should be targeted at neighborhoods with lower percentages of public transport use.

Moreover, as shown in Fig. 7d, increases in the percentage of people living the drivers’ residency neighborhoods who were born in the UK were associated with increases in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity level. Therefore, driver safety education and other behavioural change programs should be targeted at neighborhoods with around 0.6% indigenous people and higher proportions of people who were born in the UK.

Crash Location Neighborhood Characteristics

As shown in Fig. 3, the population density of the crash location was an important factor contributing to vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. This result was similar to those of La Scala et al. [60], Clifton et al. [61] and Toran pour et al. [24], which showed that changes in population density might influence vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. According to Fig. 8a, increases in the population density were associated with slight and gradual increases in the likelihood of serious injuries in vehicle-pedestrian crashes. However, increases in the population density, particularly between 1000 and 2000 people per square km, were associated with decreases in the likelihood of fatality.

As shown in Fig. 8b, c, a larger number of people with technical or “other” education living in the location of the crash would be associated with an increase in the probability of serious vehicle-pedestrian crashes. These results were expected because the land use and jobs available in each suburb might attract people with specific education type and level, income and occupations. Additionally, it might influence the driving and walking behaviors in the neighborhood, the quality of the road and the swiftness of emergency responses in the event of a crash.

Therefore, site-specific road safety countermeasures, such as road safety audits, engineering treatments and enforcement activities should be targeted at neighborhoods with high population densities and higher percentages of people with technical or “other” education. Additionally, site-specific road safety messages could be used to alert road users and change driver and pedestrian behavior in these areas.

Conclusion

Identifying contributing factors in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity could assist transportation engineers, road safety professionals and policy makers in developing and implementing effective countermeasures to reduce the number of pedestrian deaths and injuries. In this research, the BDT model was applied to identify the contribution of socioeconomic factors related to locations of crashes, and also pedestrians’ and drivers’ residency neighborhoods. Results of this research would provide valuable information to assist road safety professional in targeting the right neighborhoods to implement different safety measures related to pedestrians and drivers, as well as targeting site-specific safety measures to reduce vehicle-pedestrian crashes.

This study found that neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics accounted for 12 out of the 20 most important variables in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity at mid-blocks. Moreover, this research revealed that nine of these 12 socioeconomic variables were related to pedestrians’ and drivers’ residency neighborhoods, which showed the importance of factors related to residency neighborhoods compared to factors related to the location of crashes.

This research found that public transport use and family background were the two most important factors affecting vehicle-pedestrian crash severity that were related to the pedestrians’ residency neighborhoods. According to the results of this research, neighborhoods with high public transport usage, and higher proportions of people born in the UK, could be targeted for measures to improve the safety of pedestrians, such as pedestrian safety educational programs.

This study also found that the level of education, ethnicity and usage of public transport in the drivers’ residency neighborhoods were important contributing factor in vehicle-pedestrian crash severity. This research showed that drivers’ behavior modification programs need to be targeted at neighborhoods with higher proportions of people with technical and trade education, higher proportions of people who were born in the UK and neighborhood with around 0.6% of the population with indigenous background. Raising the awareness of drivers in these targeted neighborhoods about vehicle-pedestrian safety and developing other driver safety campaigns would decrease the number of injuries and deaths related to vehicle-pedestrian crashes.

Further, this research found that population density and the percentage of people with technical or trade education had important effects on the location and severity of vehicle-pedestrian crashes. This research provided some evidence to support the recommendation that site-specific engineering, enforcement and safety messages should be applied in neighborhoods with higher population density and larger shares of people with technical or trade education.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that this research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Pucher J, Dijkstra L. Promoting safe walking and cycling to improve public health: lessons from The Netherlands and Germany. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1509–1516. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Global status report on road safety 2015. Geneva , Switzerland: World Health Organization, Department of Violence & Injury Prevention & Disability (VIP). 2015

- 3.Rifaat S, Tay R, Perez A, Barros AD. Effects of neighborhood street patterns on traffic collision frequency. J Transp Safety & Security. 2009;1(4):241–253. doi: 10.1080/19439960903328595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rifaat SM, Tay R, de Barros A. Urban street pattern and pedestrian traffic safety. J Urban Design. 2012;17(3):337–352. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2012.683398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Ranjitkar P, Zhao Y, Yi H, Rashidi S. Analyzing pedestrian crash injury severity under different weather conditions. Traffic Inj Prev. 2016:00–0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Tay R, Choi J, Kattan L, Khan A. A multinomial logit model of pedestrian–vehicle crash severity. Int J Sustain Transp. 2011;5(4):233–249. doi: 10.1080/15568318.2010.497547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHTSA NCfSaA. Pedestrians: 2014 data. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2016. DOT HS 812 270.

- 8.Mohamed MG, Saunier N, Miranda-Moreno LF, Ukkusuri SV. A clustering regression approach: a comprehensive injury severity analysis of pedestrian–vehicle crashes in New York, US and Montreal. Canada Saf Sci. 2013;54:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2012.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eluru N, Bhat CR, Hensher DA. A mixed generalized ordered response model for examining pedestrian and bicyclist injury severity level in traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(3):1033–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J-K, Ulfarsson GF, Shankar VN, Mannering FL. A note on modeling pedestrian-injury severity in motor-vehicle crashes with the mixed logit model. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42(6):1751–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ukkusuri S, Miranda-Moreno LF, Ramadurai G, Isa-Tavarez J. The role of built environment on pedestrian crash frequency. Saf Sci. 2012;50(4):1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2011.09.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones AP, Haynes R, Harvey IM, Jewell T. Road traffic crashes and the protective effect of road curvature over small areas. Health & Place. 2012;18(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballesteros MF, Dischinger PC, Langenberg P. Pedestrian injuries and vehicle type in Maryland, 1995–1999. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00129-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho G, Rodríguez DA, Khattak AJ. The role of the built environment in explaining relationships between perceived and actual pedestrian and bicyclist safety. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(4):692–702. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clifton KJ, Kreamer-Fults K. An examination of the environmental attributes associated with pedestrian–vehicular crashes near public schools. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(4):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gårder PE. The impact of speed and other variables on pedestrian safety in Maine. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(4):533–542. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miranda-Moreno LF, Morency P, El-Geneidy AM. The link between built environment, pedestrian activity and pedestrian–vehicle collision occurrence at signalized intersections. Accid Anal Prev. 2011;43(5):1624–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campos-Outcalt D, Bay C, Dellapenna A, Cota MK. Pedestrian fatalities by race/ethnicity in Arizona, 1990–1996. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00465-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougherty G, Pless IB, Wilkins R. Social class and the occurrence of traffic injuries and deaths in urban children. Can J Public Health. 1990;81(3):204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyons RA, Towner E, Christie N, et al. The advocacy in action study a cluster randomized controlled trial to reduce pedestrian injuries in deprived communities. Inj Prev. 2008;14(2):e1. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cottrill CD, Thakuriah P. Evaluating pedestrian crashes in areas with high low-income or minority populations. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42(6):1718–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borrell C, Plasència A, Huisman M, et al. Education level inequalities and transportation injury mortality in the middle aged and elderly in European settings. Inj Prev. 2005;11(3):138–142. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amoh-Gyimah R, Sarvi M, Saberi M. Investigating the Effects of Traffic, Socioeconomic, and Land Use Characteristics on Pedestrian and Bicycle Crashes: A Case Study of Melbourne, Australia. Paper presented at: Transportation Research Board 95th Annual Meeting; 2016.

- 24.Toran Pour A, Moridpour S, Tay R, Rajabifard A. Modelling pedestrian crash severity at mid-blocks. Transportmetrica A: Transp Sci. 2017;13(3):273–297. doi: 10.1080/23249935.2016.1256355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wier M, Weintraub J, Humphreys EH, Seto E, Bhatia R. An area-level model of vehicle-pedestrian injury collisions with implications for land use and transportation planning. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(1):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham D, Glaister S, Anderson R. The effects of area deprivation on the incidence of child and adult pedestrian casualties in England. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(1):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilde GJS. Social interaction patterns in driver behavior: an introductory review. Hum Factors. 1976;18(5):477–492. doi: 10.1177/001872087601800506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishaque MM, Noland RB. Behavioural issues in pedestrian speed choice and street crossing behaviour: a review. Transp Rev. 2008;28(1):61–85. doi: 10.1080/01441640701365239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Factor R, Mahalel D, Yair G. The social accident: a theoretical model and a research agenda for studying the influence of social and cultural characteristics on motor vehicle accidents. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(5):914–921. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agran PF, Winn DG, Anderson CL, Del Valle C. Family, social, and cultural factors in pedestrian injuries among Hispanic children. Inj Prev. 1998;4(3):188–193. doi: 10.1136/ip.4.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coughenour C, Clark S, Singh A, Claw E, Abelar J, Huebner J. Examining racial bias as a potential factor in pedestrian crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;98:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census Dictionary. In. Vol Cat no. 2901.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2001.

- 33.Chang L-Y, Wang H-W. Analysis of traffic injury severity: an application of non-parametric classification tree techniques. Accid Anal Prev. 2006;38(5):1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashani AT, Mohaymany AS. Analysis of the traffic injury severity on two-lane, two-way rural roads based on classification tree models. Saf Sci. 2011;49(10):1314–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2011.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Lord D, Zhang Y, Xie Y. Predicting motor vehicle crashes using support vector machine models. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(4):1611–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abellán J, López G, de Oña J. Analysis of traffic accident severity using decision rules via decision trees. Expert Syst Appl. 2013;40(15):6047–6054. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2013.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang L-Y, Chien J-T. Analysis of driver injury severity in truck-involved accidents using a non-parametric classification tree model. Saf Sci. 2013;51(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2012.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung S, Qin X, Oh C. Improving strategic policies for pedestrian safety enhancement using classification tree modeling. Transp Res A Policy Pract. 2016;85:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2016.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lord D, van Schalkwyk I, Chrysler S, Staplin L. A strategy to reduce older driver injuries at intersections using more accommodating roundabout design practices. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(3):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pham M-H, Bhaskar A, Chung E, Dumont A-G. Random forest models for identifying motorway rear-end crash risks using disaggregate data. Paper presented at: Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 2010 13th International IEEE Conference; 2010.

- 41.Jiang X, Abdel-Aty M, Hu J, Lee J. Investigating macro-level hotzone identification and variable importance using big data: a random forest models approach. Neurocomputing. 2016;181:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2015.08.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung Y-S. Factor complexity of crash occurrence: an empirical demonstration using boosted regression trees. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;61:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee C, Li X. Predicting driver injury severity in single-vehicle and two-vehicle crashes with boosted regression trees. Transp Res Record: J Transp Res Board. 2015;2514:138–148. doi: 10.3141/2514-15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu C, Liu P, Wang W, Li Z. Identification of freeway crash-prone traffic conditions for traffic flow at different levels of service. Transp Res A Policy Pract. 2014;69:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2014.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elith J, Leathwick JR, Hastie T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J Anim Ecol. 2008;77(4):802–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001:1189–232.

- 47.Matignon R. Data Mining Using SAS Enterprise Miner. South Sanfrancisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2007.

- 48.Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. Classification and regression trees. New York: CRC press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ridgeway G. Generalized boosted models: a guide to the gbm package. Update. 2007;1(1):2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2013. In: ISBN 3–900051–07-0; 2014.

- 51.Kuhn M. Caret package. J Stat Softw. 2008;28(5).

- 52.Verzosa N, Miles R. Severity of road crashes involving pedestrians in metro manila. Philippines Accid Anal Prev. 2016;94:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harwood DW, Bauer KM, Richard KR, et al. Pedestrian Safety Prediction Methodology. NCHRP Web-only Document 129: Phase III. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC (2008). 2008.

- 54.Tulu GS, Washington S, Haque MM, King MJ. Investigation of pedestrian crashes on two-way two-lane rural roads in Ethiopia. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;78:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noland RB, Oh L. The effect of infrastructure and demographic change on traffic-related fatalities and crashes: a case study of Illinois county-level data. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(4):525–532. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rifaat S, Tay R, de Barros A. Effect of land use, road infrastructure, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics on public transit usage. Paper presented at: International Conference of the Hong Kong Society for Transportation Studies (HKSTS), 16th, 2011, Hong Kong; 2011.

- 57.Sze NN, Wong SC. Diagnostic analysis of the logistic model for pedestrian injury severity in traffic crashes. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(6):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shinar D, Schechtman E, Compton R. Self-reports of safe driving behaviors in relationship to sex, age, education and income in the US adult driving population. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33(1):111–116. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(00)00021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hassan HM, Shawky M, Kishta M, Garib AM, Al-Harthei HA. Investigation of drivers’ behavior towards speeds using crash data and self-reported questionnaire. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;98:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2016.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.LaScala EA, Gerber D, Gruenewald PJ. Demographic and environmental correlates of pedestrian injury collisions: a spatial analysis. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32(5):651–658. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clifton KJ, Burnier CV, Akar G. Severity of injury resulting from pedestrian–vehicle crashes: what can we learn from examining the built environment? Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ. 2009;14(6):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]