Abstract

Background

State-of-the-art strain engineering techniques for the host Pichia pastoris (syn. Komagataella spp.) include overexpression of homologous and heterologous genes, and deletion of host genes. For metabolic and cell engineering purposes the simultaneous overexpression of more than one gene would often be required. Very recently, Golden Gate based libraries were adapted to optimize single expression cassettes for recombinant proteins in P. pastoris. However, an efficient toolbox allowing the overexpression of multiple genes at once was not available for P. pastoris.

Methods

With the GoldenPiCS system, we provide a flexible modular system for advanced strain engineering in P. pastoris based on Golden Gate cloning. For this purpose, we established a wide variety of standardized genetic parts (20 promoters of different strength, 10 transcription terminators, 4 genome integration loci, 4 resistance marker cassettes).

Results

All genetic parts were characterized based on their expression strength measured by eGFP as reporter in up to four production-relevant conditions. The promoters, which are either constitutive or regulatable, cover a broad range of expression strengths in their active conditions (2–192% of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter P GAP), while all transcription terminators and genome integration loci led to equally high expression strength. These modular genetic parts can be readily combined in versatile order, as exemplified for the simultaneous expression of Cas9 and one or more guide-RNA expression units. Importantly, for constructing multigene constructs (vectors with more than two expression units) it is not only essential to balance the expression of the individual genes, but also to avoid repetitive homologous sequences which were otherwise shown to trigger “loop-out” of vector DNA from the P. pastoris genome.

Conclusions

GoldenPiCS, a modular Golden Gate-derived P. pastoris cloning system, is very flexible and efficient and can be used for strain engineering of P. pastoris to accomplish pathway expression, protein production or other applications where the integration of various DNA products is required. It allows for the assembly of up to eight expression units on one plasmid with the ability to use different characterized promoters and terminators for each expression unit. GoldenPiCS vectors are available at Addgene.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12918-017-0492-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pichia pastoris, Cell engineering, Golden Gate cloning, GoldenMOCS, GoldenPiCS, Synthetic biology

Background

The yeast Pichia pastoris (syn. Komagataella spp.) is frequently applied for the production of heterologous proteins, most of which are efficiently secreted [1]. It is also favored for the production of membrane proteins [2], pharmaceuticals and chemical compounds [3] and as a model organism for biomedical research [4]. New genetic tools for P. pastoris such as promoters, signal peptides, selection markers, Flp-frt/Cre-lox recombination and CRISPR/Cas9 have been reviewed recently [3]. Compared to other yeast species, P. pastoris is distinguished by its methylotrophy, its Crabtree-negative metabolism, its growth to very high cell densities, the low number and concentration of secreted host cell proteins [5] and the availability of many genetic tools and industrially relevant strains (humanized N-glycosylation, protease deficiency) [6]. Genomic integration into specific loci is usually applied by using 5′ and 3′ homologous regions and is crucially depending on the avoidance of repetitive homologous regions and the use of well-purified vector DNA [7].

For recombinant protein production in P. pastoris, different highly efficient promoter systems were established (reviewed by Weinhandl et al. [8]) and applied to produce up to several grams per liter of secreted heterologous products, covering proteins intended for biopharmaceutical purposes as well as industrial enzymes [9]. The methanol utilization (MUT) pathway of P. pastoris is very efficient and the corresponding genes are highly induced on methanol [10, 11]. MUT promoters (e.g. P AOX1, P DAS1/2 and P FLD1) as well as strong constitutive promoters from highly expressed genes (such as P GAP, derived from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene TDH3 and the promoter of translation elongation factor P TEF1) are frequently applied [12]. Nevertheless, there is still room to further improve productivity and/or protein quality. Besides increasing transcriptional strength by using strong promoters and higher gene copy numbers of the expression cassettes, also cell engineering to boost the host’s folding and secretion capacity or to provide precursors and energy for these processes proved to be beneficial for enhancing product titers (reviewed by Puxbaum et al. [1]). Sometimes such cell engineering approaches require the simultaneous overexpression of more than one gene to reach their full potential (e.g. Nocon et al. [13], Delic et al. [14]). On the other hand, gene knock-outs might be necessary to avoid detrimental processes such as transport to the vacuole or proteolysis (e.g. Idiris et al. [15]). Both of these genetic manipulations require extensive cloning and transformation efforts, which makes them rather time-consuming and tedious.

Today, advanced synthetic biology tools are applied in all fields of microbiology. New cloning methods such as Gateway®, Gibson Assembly and Golden Gate cloning, together with genome editing techniques like CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN (transcription activator-like effector nucleases), enable efficient and highly specific cell engineering and thereby revolutionized the whole field [16]. Golden Gate cloning is based on type IIs restriction enzymes (which are cutting outside of their recognition sequence) and offers important benefits: it does not require long flanking DNA, it uses efficient one-pot reactions, allows scar-less cloning and is cost-saving compared to many other advanced techniques [17]. In Golden Gate Assembly (GGA), the two different type IIs restriction endonucleases BsaI and BpiI are used which yield four base pair overhangs outside of their recognition sequence. These overhangs can be freely designed and are termed fusion sites (Fs). These fusion sites enable base pair precise assembly of genetic parts such as promoters, coding sequences (CDS) and transcription terminators. By using simultaneous restriction and ligation in efficient one-pot cloning reactions, rapid assembly of multiple DNA fragments is achieved [17].

Recently, Obst et al. [18] and Schreiber et al. [19] reported the use of Golden Gate cloning for the generation of libraries of expression cassettes in P. pastoris, which were tested for the production of reporter proteins by the assembly of standardized parts such as promoters, ribosome binding sites, secretion signals and terminators in a fast and efficient way. These studies aimed to optimize a single transcription unit for the production of one heterologous protein of interest (either a fluorescent reporter or an antimicrobial peptide). Vogl et al. [20] used Gibson assembly with a set of MUT-related promoters and novel transcription terminators for the overexpression of multiple genes in P. pastoris and could show a strong effect of the inserted promoters when overexpressing the carotenoid pathway (crtE, crtB, crtI, and crtY). Our study extends the versatile Golden Gate technique for all applications in P. pastoris where the simultaneous integration of multiple DNA products is required (e.g. cell engineering, pathway expression, protein production, co-expression of cofactors) and aims beyond the mere assembly of single expression cassettes for the heterologous protein of interest.

For this purpose, we adapted the Golden Gate based modular cloning (MoClo) introduced by Weber et al. [21], to create the GoldenPiCS (Golden Gate derived P. pastoris cloning system) vector toolkit. GoldenPiCS is part of a universal system termed GoldenMOCS, standing for Golden Gate-derived Multiple Organism Cloning System [22]. The GoldenMOCS platform enables versatile integration of host specific parts such as promoters, terminators, and resistance cassettes, origins of replication or genome integration loci to adapt the plasmid to the needs of the experiment and the host cell to be engineered. Here, we present the GoldenMOCS- subsystem GoldenPiCS designed for use in P. pastoris and the characterization of its individual genetic parts using eGFP (enhanced green fluorescence protein) as a reporter. Vectors of these systems were deposited at Addgene as GoldenPiCS kit (#1000000133).

Results and discussion

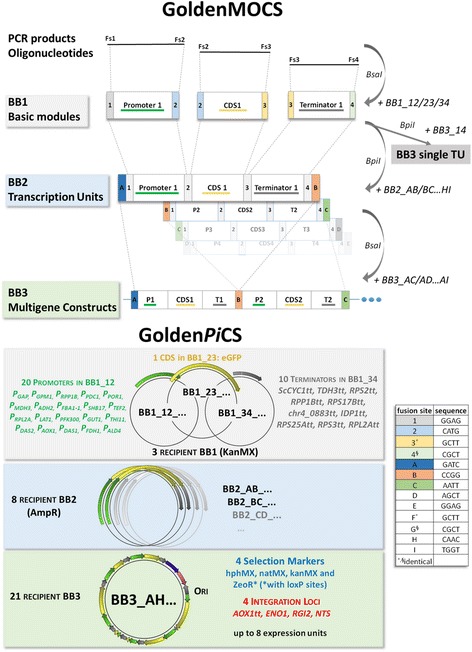

GoldenPiCS, our Golden Gate-derived P. pastoris cloning system, consists of three hierarchical backbone (BB) levels for flexible generation of overexpression plasmids containing multiple transcription units (up to eight per plasmid), four different selection markers and five loci either for targeted genome integration or episomal plasmid maintenance (Fig. 1). We mainly designed the system to enable advanced cell engineering or the expression of whole metabolic pathways. In the lowest cloning level, individual parts such as promoters, coding sequences (e.g. reporters or GOIs) and transcription terminators are incorporated into backbone 1 (BB1) plasmids, which are subsequently assembled to one transcription unit in BB2. This is followed by the assembly of multiple expression units into one BB3, which is designed for subsequent genome integration in P. pastoris (four different selection markers and four loci for targeted genome integration are available). Contrary to other cloning techniques, Golden Gate Assembly avoids the need for excessive sequencing, because BB2 and BB3 constructs are assembled by ligation instead of overlap-extension PCR (only BB1 inserts require sequencing after assembly). Correct ligation is assured by defined fusion sites (see Fig. 1): Fusion sites Fs1 to Fs4 are linked to individual parts by PCR and required for their assembly into a transcription unit (BB2) e.g. promoters with coding sequences (‘CATG’, fusion site Fs2). Fusion sites FsA to FsI are used for the assembly of multiple expression units in BB3 e.g. for fusing the first transcription unit to the second (‘CCGG’, fusion site FsB). The different BB3 vectors with fusion sites FsA-FsC, FsA-FsD, to FsA-FsI are designed for the assembly of two, three, … up to eight transcription units in one single plasmid. Internal BsaI and BpiI restriction sites must be removed in all modules by introducing point mutations, with consideration of the codon usage of P. pastoris.

Fig. 1.

Assembly strategy and hierarchical backbone levels of the cloning systems GoldenMOCS and GoldenPiCS. In the microorganism-independent general platform GoldenMOCS, DNA products (synthetic DNA, PCR products or oligonucleotides) are integrated into BB1 by a BsaI Golden Gate Assembly and fusion sites Fs1, Fs2, Fs3 and Fs4. Fusion sites are indicated as colored boxes with corresponding fusion site number or letter. Basic genetic elements contained in backbone 1 (BB1) can be assembled in recipient BB2 by performing a BpiI GGA reaction. The transcription units in BB2 are further used for BsaI assembly into multigene BB3 constructs. Single transcription units can be obtained by direct BpiI assembly into recipient BB3 with fusion sites Fs1-Fs4. Fusion sites determine module and transcription unit positions in assembled constructs. Thereby, fusion sites Fs1 to Fs4 are used to construct single expression cassettes in BB2 and are required between promoter (Fs1-Fs2), CDS (Fs2-Fs3) and terminator (Fs3-Fs4). Fusion sites FsA to FsI are designed to construct BB3 plasmids and separate the different expression cassettes from each other. The FSs are almost randomly chosen sequences and only FS2 has a special function, because it includes the start codon ATG. GoldenPiCS additionally includes module-containing BB1s specific for P. pastoris: 20 promoters, 1 reporter gene (eGFP) and 10 transcription terminators, and recipient BB3 vectors containing different integration loci for stable genome integration in P. pastoris and suitable resistance cassettes (Additional file 2)

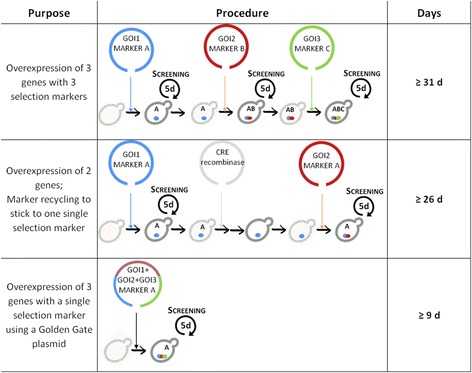

Previously, strain engineering approaches with P. pastoris often relied on pGAPz, pPIC6 (Invitrogen) or related expression vectors, which harbor only one transcription unit (Fig. 2). Cloning of concatemers containing more than two transcription units proved to be highly time consuming and also led to unpredictable integration events when using repetitive promoter and terminator sequences [23, 24]. Therefore, conventional overexpression of n genes requires n cycles of preparing competent cells and transforming them, and the use of n different selection markers. For overexpression of three factors plus screenings using consecutive transformations, the procedure would take at least 31 days (four days for transformation and re-streak, five days for screening and two days to prepare competent cells; Fig. 2, upper panel). Furthermore, selection markers can be removed and recycled, with the cost of an additional cycle of competent-making and transformation (Fig. 2, middle panel). In addition to that, the use of different integration loci must be included to prevent ‘loop-out’ incidents of integrated DNA. Alternatively, co-transformation of multiple vectors can be considered, but this requires the use of several independent selection markers, otherwise in our experience transformation efficiency is low and it is very unpredictable if all vectors get integrated into the genome [25]. Our backbone BB3 Golden Gate plasmids can carry multiple transcription units and hence significantly simplify and shorten the procedure to one single transformation step. Integration of multiple transcription units plus screening lasts only nine days (Fig. 2, lower panel). The thereby generated strains benefit from decreased generation numbers and milder selection procedures.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of conventional and Golden Gate based strain engineering strategies for P. pastoris. Overexpression of multiple genes (GOIs) in P. pastoris using conventional cloning plasmids requires several rounds of competent making (2 days), transformation (4 days including second streak-out) and clone screening (5 days) and takes at least 31 days for three genes with three selection markers. Alternatively, multiple vectors can be co-transformed at once, but resulting transformation efficiencies are usually very low and clonal variation increases. Appropriate flanking sites for the selection marker (loxP or FRT sites) enable marker recycling by recombinases (Cre or Flp, respectively), but require one more round of competent making and transformation which takes at least eight additional days. Golden Gate plasmids carry several transcription units at once and thereby enable transformation and screening in only nine days

Recombination events by repetitive sequences disturb full vector integration in P. pastoris

Initially, we started with Golden Gate vectors carrying up to four transcription units with the same promoter and transcription terminator (P GAP and ScCYC1tt). High clonal variation prompted us to analyze gene copy numbers (GCN) of integrated genes and we found that individual transcription units were lost. Similar results have been obtained with P GAP or P AOX1 based multicopy vectors [24], thus showing that incomplete vector integration is not due to the Golden Gate backbone. We positively confirmed post-transformational integration stability for three of the transformants in three consecutive shake flask- batch cultivations without selection pressure (gene copy numbers were stable for more than 15 generations; Additional file 1: Table S1). Therefore, we conclude that repetitive homologous sequences within the expression vector (P GAP and ScCYC1tt sequences) resulted in recombination events (internal ‘loop out’) during transformation.

The high occurrence of incomplete vector integration prompted us to establish a collection of 20 different promoters and 10 transcription terminators (Table 1), in order to avoid repetitive sequences when creating constructs carrying multiple expression units. Promoters and terminators were selected based on the transcriptional regulation and expression strength of their natively controlled genes in published microarray experiments [26]. All of them were screened in several production-relevant conditions (Additional file 1: Table S2). In addition to established promoters [3, 12], we selected novel yet uncharacterized promoter sequences based on their expression behavior in transcriptomics data from P. pastoris cells cultivated on different carbon sources [26]. By applying this collection we aimed to gain the ability to fine-tune the expression of integrated genes. Ideally, promoters for cell engineering purposes should cover a wide range of expression strengths and allow constitutive as well as tunable expression. Transcription terminators were selected from constitutively highly expressed genes [26], many of them being derived from ribosomal protein genes. Also ribosomal genes were reported to be regulated at the level of mRNA stability [27], which is one of the main functions of the 3’UTR contained in the transcription terminator fragments.

Table 1.

Promoters and terminators of the P. pastoris GoldenPiCS toolbox

| Promoter/Terminator | Short Name | Gene name | ORF | length [bp] | μA mean exp. G | μA mean exp. X | μA mean exp. D | μA mean exp. M | rel. eGFP [%] G | rel. eGFP [%] X | rel. eGFP [%] D | rel. eGFP [%] M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P GAP | TDH3 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr2–0858 | 496 | 175,734 | 153,293 | 190,970 | 89,048 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| P GPM1 | GPM1 | phosphoglycerate mutase | PP7435_Chr3–0360 | 404 | 118,686 | 98,941 | 165,884 | 52,844 | 25 | 13 | 26 | 11 |

| P RPP1B | RPP1B | ribosomal protein P1 beta | PP7435_Chr4–0276 | 999 | 168,241 | 88,081 | 147,457 | 134,220 | 22 | 14 | 23 | 13 |

| P PDC1 | PDC1 | pyruvate decarboxylase 1 | PP7435_Chr3–1042 | 989 | 95,047 | 34,921 | 188,242 | 24,093 | 19 | 17 | 23 | 16 |

| P POR1 | POR1 | mitochondrial porin | PP7435_Chr2–0411 | 704 | 94,576 | 173,321 | 58,699 | 118,862 | 46 | 28 | 19 | 51 |

| P MDH3 | MDH3 | peroxisomal malate dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr4–0136 | 979 | 26,497 | 206,905 | 12,554 | 87,661 | 76 | 83 | 17 | 110 |

| P ADH2 | ADH2 | alcohol dehydrogenase 2 | PP7435_Chr2–0821 | 820 | 117,961 | 165,203 | 140,678 | 61,540 | 33 | 47 | 16 | 54 |

| P FBA1–1 | FBA1–1 | fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | PP7435_Chr1–0374 | 970 | 152,990 | 127,354 | 213,816 | 57,961 | 20 | 11 | 14 | 12 |

| P SHB17 | SHB17 | sedoheptulose bisphosphatase | PP7435_Chr2–0185 | 995 | 24,473 | 43,866 | 35,852 | 167,426 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 |

| P TEF2 | TEF2 | translational elongation factor EF-1 alpha | PP7435_Chr1–1535 | 572 | 184,546 | 96,226 | 180,287 | 161,445 | 53 | |||

| P RPL2A | RPL2A | ribosomal 60S subunit protein L2A | PP7435_Chr4–0909 | 949 | 184,025 | 96,715 | 164,082 | 143,041 | 10 | |||

| P LAT1 | LAT1 | dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase | PP7435_Chr1–0349 | 1006 | 24,576 | 22,867 | 31,661 | 16,960 | 6 | |||

| P PFK300 | PFK300 | Gamma subunit of 6-phosphofructokinase | PP7435_Chr4–0686 | 229 | 20,845 | 18,516 | 21,844 | 15,474 | 2 | |||

| P GUT1 | GUT1 | glycerol kinase | PP7435_Chr4–0173 | 1305 | 31,172 | 88,114 | 1324 | 12,564 | 44 | 1 | ||

| P THI11 | THI11 | involved in synthesis of thiamine precursor | PP7435_Chr4–0952 | 1005 | 77,578 | 101,948 | 45,756 | 120,542 | 36 | |||

| P DAS2 | DAS2 | dihydroxyacetone synthase 2 | PP7435_Chr3–0350 | 1005 | 1316 | 32,401 | 1268 | 186,477 | 0 | 160 | ||

| P AOX1 | AOX1 | alcohol oxidase 1 | PP7435_Chr4–0130 | 928 | 5301 | 159,461 | 4487 | 188,502 | 0 | 105 | ||

| P DAS1 | DAS1 | dihydroxyacetone synthase 1 | PP7435_Chr3–0352 | 554 | 2518 | 45,547 | 2200 | 239,261 | 0 | 99 | ||

| P FDH1 | FDH1 | formate dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr3–0238 | 1032 | 3126 | 215,618 | 2418 | 179,036 | 0 | 83 | ||

| P ALD4 | ALD4 | mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr2–0787 | 869 | 21,239 | 109,237 | 9330 | 52,434 | 0 | 18 | ||

| ScCYC1tt | YJR048W | cytochrome C isoform 1 | Sc: YJR048W | 285 | – | – | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| TDH3tt | TDH3 | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr2–0858 | 210 | 175,734 | 153,293 | 190,970 | 89,048 | 139 | 128 | 126 | |

| RPS2tt | RPS2 | protein component of the 40S ribosome | PP7435_Chr1–1396 | 476 | 161,620 | 77,215 | 151,802 | 135,407 | 136 | 129 | 128 | |

| RPP1Btt | RPP1B | ribosomal protein P1 beta | PP7435_Chr4–0276 | 507 | 168,241 | 88,081 | 147,457 | 134,220 | 120 | 117 | 113 | |

| RPS17Btt | RPS17B | ribosomal protein 51 | PP7435_Chr2–0491 | 495 | 122,828 | 89,591 | 125,205 | 117,162 | 124 | 122 | 118 | |

| chr4_0883tt | chr4_0883 | not conserved hypothetical protein | PP7435_Chr4–0069 | 483 | 127,795 | 93,922 | 95,185 | 113,403 | 88 | 99 | 84 | |

| IDP1tt | IDP1 | mitochondrial NADP-specific isocitrate dehydrogenase | PP7435_Chr1–0546 | 503 | 11,349 | 8309 | 19,236 | 10,932 | 126 | 123 | 118 | |

| RPS25Att | RPS25A | protein component of the 40S ribosome | PP7435_Chr2–0346 | 493 | 146,211 | 100,973 | 140,035 | 126,110 | 140 | 126 | 123 | |

| RPS3tt | RPS3 | protein component of the 40S ribosome | PP7435_Chr1–0118 | 174 | 143,928 | 59,278 | 143,257 | 121,372 | 137 | 125 | 123 | |

| RPL2Att | RPL2A | ribosomal 60S subunit protein L2A | PP7435_Chr4–0909 | 504 | 184,025 | 96,715 | 164,082 | 143,041 | 102 | 102 | 93 |

Mean expression from microarray (μA) data were extracted from [26]. The relative eGFP expression is related to expression under control of PGAP in the respective condition

G 2% glycerol, X glucose feed bead (limited glucose), D 2% glucose, M methanol

Validation of Kozak sequence mutations in the PGAP sequence of P. pastoris

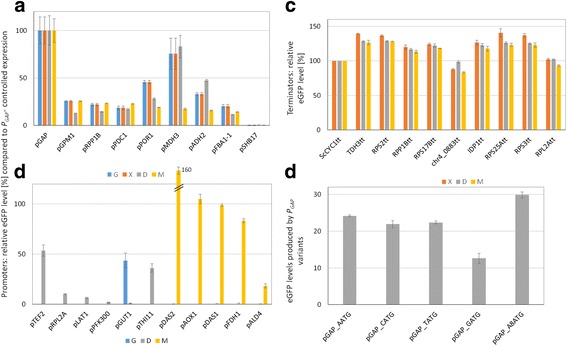

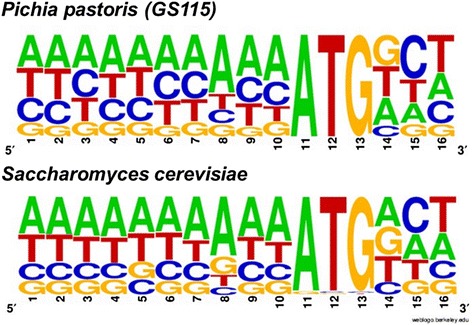

In the GoldenMOCS setup, fusion site Fs2 that links the promoter to the GOI contains the start codon ATG and part of the Kozak sequence, which is important for translational initiation in eukaryotes. As this fusion site is a fixed variable in the Golden Gate system, we evaluated the effect of the ‘-1’ position of the P GAP promoter (position in front of the start codon, Fig. 3d) on reporter gene expression in P. pastoris. Due to the ‘CATG’ fusion site, the native ‘A’ in position ‘-1’ of the P GAP promoter (‘-8’ to ‘-1’: AAAACACA) is changed to ‘C’ (AAAACACC). While P GAP variants with ‘A’, ‘T’ and ‘C’ at position ‘-1’ performed similarly, the variant with ‘G’ resulted in a lower eGFP level (P GAP_GATG; about 40% lower compared to the other variants). The Kozak consensus sequence of P. pastoris was analyzed and found to be similar to that of S. cerevisiae, which is rich in ‘A’ and poor in ‘G’ bases (Fig. 4). Based on these results, eight bases of the A-rich Kozak consensus sequence were tested in an additional P GAP variant (P GAP_A8ATG; position ‘-4’ and ‘-2’ replaced by ‘A’: AAAAAAAA) and a slightly increased expression of eGFP was found (Fig. 3d). Nevertheless, we chose the ‘CATG’ fusion site for our GoldenPiCS system and kept the ‘GCTT’ fusion site for the GOI-terminator assembly.

Fig. 3.

Relative eGFP levels obtained with various elements of the GoldenPiCS toolbox. Expression strength of different promoters in comparison to P GAP tested on different carbon sources (a, b), expression levels for P GAP-controlled expression in combination with different transcriptional terminators (c), and comparison of P GAP variants with alternative ‘-1’ nucleotides (d). At least 10 P. pastoris clones were screened to test promoter and terminator function in up to four different conditions: glycerol and glucose excess as present in batch cultivation (“G”, “D”), limiting glucose (“X”) and methanol feed (“M”), both representing fed batch. P GAP to P SHB17 were tested in ‘G’, ‘D’, ‘X’ and ‘M’ (A). P TEF2 to P PFK300 were validated in ‘D’, while P GUT1, P THI11 and MUT-related promoters were tested in putative repressed and induced conditions (‘D’/‘G’, ‘D’+/−100 μM thiamine and ‘D’/M, respectively) (B). P GAP variants with alternative ‘-1’ bases were analyzed in glucose excess (‘D’). Relative eGFP levels are related to P GAP- controlled expression (A, B), terminator ScCYC1tt (B), or presented as relative value (C)

Fig. 4.

Kozak consensus sequences of P. pastoris and S. cerevisiae. The sequences were retrieved by the regulatory sequence analysis tool (RSAT) and illustrated using weblogo

Analysis of GoldenPiCS promoter and terminator strength and regulation using eGFP

All promoters and terminators were characterized for their capacity for expression of the intracellular reporter eGFP in appropriate conditions (Additional file 1: Table S2): glycerol or glucose excess (“G” and “D”, respectively, maximum specific growth rate μMAX~0.22 h−1) as present in batch cultivation, limiting glucose (“X”, 12 mm glucose feed beads, specific growth rate μ~ 0.04 h−1) and methanol feed (“M”, μMAX up to 0.1 h−1), the latter two representing conditions as encountered during fed batch cultivation. P GAP was used as reference to evaluate the expression strength of the promoters. P TEF2, P GPM1, P RPP1B, P PDC1, P POR1, P ADH2, P FBA1–1, P RPL2A, P LAT1, P PFK300 and P MDH3 were confirmed to have a constitutive regulation with a range of eGFP expression of 2–192% of P GAP in all tested conditions (Fig. 3a and b). Promoters responsive to thiamine (P THI11), glycerol (P GUT1) and methanol (P AOX1, P DAS1, P DAS2, P FDH1, P SHB17 and P ALD4) were well repressed (0% of P GAP) and induced (to 18–160% of P GAP) in the repressed and induced conditions, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 3b). The selected transcription terminator sequences did not have large effects on eGFP expression levels (tested with P GAP, normalized to termination with ScCYC1tt, Table 1 and Fig. 3c). However, eGFP levels were about 20% lower compared to the other terminators when using ScCYC1tt (also reported recently in [7]), chr4_0883tt and RPL2Att. Recently, a set of transcriptional terminators derived from MUT- and other metabolic genes of P. pastoris was tested in combination with expression under control of PAOX1 and a broader range of expression levels from 60 to 100% relative to the AOX1 terminator was observed [20]. Compared to that, transcription terminators of GoldenPiCS, which were mainly selected from ribosomal genes (reported to be regulated at the level of mRNA stability [27]), appear to result in more uniform expression levels.

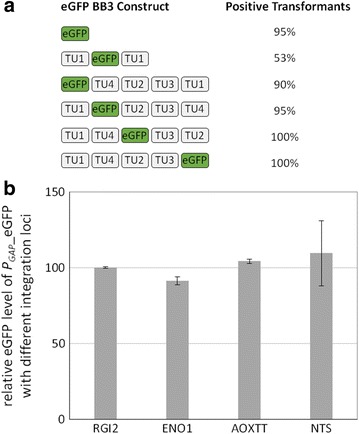

Evaluation of genome integration efficiency of GoldenPiCS multigene constructs

Vectors containing up to five transcription units without repetitive homologous sequences, including P GAP_eGFP_ScCYC1tt in different positions of the vector as readout, resulted in complete vector integration for more than 97% of all P. pastoris transformants, although we observed a slight efficiency decrease with increasing distance from the selection marker (Fig. 5a). Relative eGFP levels were very similar for all tested constructs. In contrast, just 56% eGFP positive clones were obtained when a control vector containing twice the identical transcription unit with P GAP_eGFP_ScCYC1tt in between was used (only 9 out of 16 clones contained an integrated copy). To further increase our repertoire for strain engineering purposes, Golden Gate constructs containing a single eGFP transcription unit (P GAP_eGFP_ScCYC1tt) targeted to different integration loci (AOX1tt, RGI2, ENO1 or NTS) were analyzed. The eGFP levels were similar with all tested constructs expressing from different genomic loci in P. pastoris (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Genome integration efficiency of Golden Gate vectors without repetitive homologous sequences (a) and expression of eGFP obtained after integration into different genomic loci (b). Genome integration efficiency (fraction of positive clones) are shown for P. pastoris transformed with different Golden Gate vectors containing P GAP-eGFP_ScCYC1tt: control plasmid (single eGFP), eGFP in position 2 with a repetitive transcription unit (TU1) in position 1 and 3 (‘loop-out’ control) and 4 quadruple combinations with eGFP in position 1, 2, 3 and 5 next to four other transcription units TU1–4) (a). Genome integration was verified by analyzing eGFP expression of each 16 (controls) and 22 clones (quadruple combinations), respectively. TU1–4 were cloned with the promoters and transcription terminators PPOR1/RPS3tt, PPDC1/IDP1tt, PADH2/RPL2Att and PMDH3/TDH3tt, respectively. Coding sequences of TU1–4 were derived from various non-essential intracellular-protein coding genes of P. pastoris with a length of 500–2000 bp. The influence of the genomic integration locus was analyzed using vectors containing only one transcription unit (P GAP_eGFP_ScCYC1tt) (b). In both cases clones were screened under glucose surplus

Example of multi-gene construct assembly with GoldenPiCS

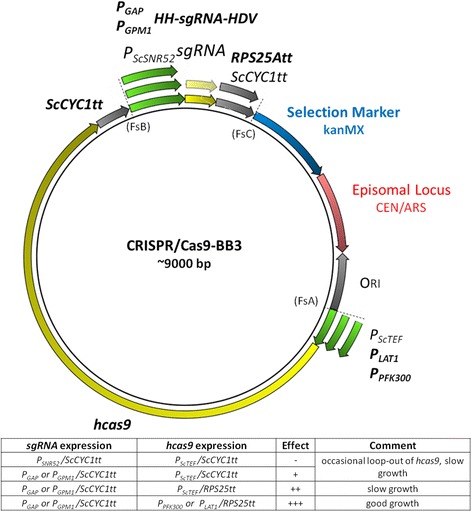

Efficient genome editing by the CRISPR/Cas9 system was shown in many organisms including P. pastoris [28]. However, efficiencies and applicability were not uniformly high when using different targets or approaches. We applied GoldenPiCS to assemble different alternatives of the two transcription units of humanized Cas9 (hcas9) and single guide RNA (sgRNA) on one single episomal plasmid and test them for their efficiency to perform InDel mutations in P. pastoris (Fig. 6). The assembled BB3 plasmids were episomally maintained in P. pastoris by using the S. cerevisiae CEN/ARS locus instead of a genome integration locus [29]. Initially, we tested sgRNA expression with the SNR52 promoter (RNAPIII promoter capable to express non-coding RNA) and the SUP4 terminator from S. cerevisiae [30], and hcas9 controlled by P ScTEF and ScCYC1tt, but we could not obtain InDel mutations in P. pastoris. Next, we tried the strong RNAPII promoter P GAP and flanking self-splicing hammerhead (HH, 5′) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV, 3′) ribozyme sequences for correct processing of the sgRNA [31] and observed an efficiency of up to 90% when targeting eGFP, similar as described by Weninger et al. [28]. To reduce potential loop-out problems of the Cas9 transcription unit encountered during expression in P. pastoris, we exchanged the ScCYC1tt terminator of the sgRNA transcription unit for the P. pastoris-derived transcription terminator RPS25Att to avoid repetitive sequences. Regarding the expression of hcas9, we obtained similarly high efficiencies with different promoters, however, growth was weaker with P ScTEF1 while it was almost unaffected when using P LAT1 or P PFK300. Targeting efficiency was mostly dependent on the applied sgRNA sequence, as we found large differences for several examples: At least two different sgRNAs designed by CHOP CHOP [32] were tested for each target. In all cases, they resulted in different efficiencies for InDel formation, e.g. two different sgRNAs each targeting AOX1 and DAS2, which are non-essential on glucose, resulted in largely different efficiencies of 38% vs. 100% and 0% vs. 100%, respectively. Therefore, we recommend to test at least two different sgRNAs for each target sequence.

Fig. 6.

Overview of CRISPR/Cas9-BB3 plasmids assembled using GoldenPiCS. Transcription units for sgRNA (fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA [42]) and hcas9 (with SV40 nuclear localization sequence at its C-terminus) with various promoters and transcription terminators were assembled in BB3cK_AC (CEN/ARS locus, KanMX selection marker, fusion sites FsA-FsC). The plasmids were successfully used to generate InDel mutations in different genomic loci and eGFP in P. pastoris. The effects of the tested constructs are summarized in the table below the vector scheme. Modules which worked most efficiently are indicated in bold in the vector scheme

With this example we demonstrate the suitability of GoldenPiCS to assemble several expression cassettes on one vector and to rapidly create new variants by exchanging parts like promoters, terminators or expression sequences. The GoldenPiCS based vectors for the described CRISP/Cas9 approach are available as separate kit at Addgene (Gassler et al. 2018.) This allowed rapid optimization of a CRISPR/Cas9-BB3 for efficient InDel mutations in P. pastoris within a short time.

Conclusions

Advanced synthetic biology tools revolutionized genetic engineering and are applied for many different organisms today. Strain engineering of P. pastoris has been shown to improve bottlenecks of protein synthesis, folding and secretion [1, 6]. Recently, we reported that overexpression of different pentose phosphate pathway genes had synergistic effects on production of human superoxide dismutase in P. pastoris [13], as were combinations of individual enzymes involved in redox homeostasis and oxidative protein folding [14]. For such complex cell engineering approaches more efficient strategies are needed. Recently, the carotenoid pathway was introduced into P. pastoris and fine-tuned by using a set of MUT-related promoters and terminators constructed by Gibson assembly [20, 33]. At about the same time, we established GoldenPiCS, a Golden Gate based modular cloning system for genetic engineering of P. pastoris. Both systems facilitate the assembly of multiple transcription units with the possibility to fine-tune the expression of each target individually. In our opinion, Golden Gate cloning has crucial advantages such as its low price, broad flexibility and high efficiency. These advantages have inspired several research groups to apply Golden Gate cloning for their purposes. So far, Golden Gate based screening in P. pastoris was dedicated to design and optimize the expression of a single recombinant gene for its production in P. pastoris by high throughput testing of different promoters and secretion signals [18, 19]. In contrast, our GoldenPiCS system is aimed to facilitate cell engineering by allowing the overexpression of multiple genes e.g. redox partners or metabolic enzymes that act in a common pathway. Therefore, our system allows for the assembly of up to eight expression units on one plasmid with the ability to use different characterized promoters and terminators for each expression unit. The latter was proven to be essential to obtain stable transformants. The toolbox described by Obst et al. [18] is based on the yeast toolkit (YTK) and is primarily designed to test gene expression of a heterologous protein of interest with different regulatory elements (with a strong focus on the comparison of different published signal peptides), but is rather limited to a subset of 4–6 strong promoters and just employs two transcription terminators, one thereof taken from the original YTK. It also overlaps with the high throughput screening platform described by Schreiber et al. [19], where two promoters and three different secretion signals were tested for the production of antimicrobial plasmids. The GoldenPiCS system is not primarily aimed for the expression screening of the heterologous protein itself (although it can be used for it), but dedicated to combinatorial cell engineering strategies or the expression of whole metabolic pathways. We have thus added an example on the assembly of CRISPR/Cas9 vectors with 2 expression cassettes, where the issue of stability with repeated sequences (and its solution with the promoter library) is illustrated, as well as the advantage of fast assembly of elements. Aside from the development of the GoldenPiCS toolkit, we have invested effort to assay promoter and terminator strength in different conditions, to validate the effect of the ‘-1’ position in front of the start codon and to present data for the ‘loop-out’ effect in P. pastoris transformants. Importantly, we found that repetitive sequences on the expression vector lead to unwanted recombination events and therefore must be avoided.

Overall, we present the hierarchical multi-organism modular cloning system (GoldenMOCS) and provide several modules and plasmids for P. pastoris: GoldenPiCS consists of 20 P. pastoris promoters, 10 terminators (all P. pastoris-derived, except for the terminator ScCYC1tt), 4 integration loci (RGI2, ENO1, NTS and AOX1tt) and one locus for episomal plasmid maintenance, as well as 4 resistance marker cassettes (hphMX, natMX, kanMX and ZeoR; the latter with loxP sites). With the currently available set of fusion sites, assembly of up to eight expression units per plasmid is possible. All of these are available through Addgene (please note that the ARS/CEN locus for episomal plasmid maintenance is only part of the CRISPR/Cas9 kit; Gassler et al. 2018) and allow high throughput assembly of multigene constructs for cell and metabolic engineering purposes.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

Escherichia coli DH10B (Invitrogen) was used for plasmid amplification. Promoter and terminator studies were done in P. pastoris (Komagataella phaffii) CBS7435(MutS), obtained from Helmut Schwab, Graz University of Technology, Austria. P. pastoris clones were screened in 24- deep well plates (Whatman, UK) using appropriate media (complex YP media or synthetic M2 screening media) [4] and selection markers (Additional file 1: Table S3). Plasmids were linearized within the genome integration locus (not applied for the episomal CRISPR/Cas9-BB3’s) and transformed into electro-competent P. pastoris by electroporation (2 kV, 4 ms, GenePulser, BioRad) according to [4].

Molecular biology

Primer design and in silico cloning was performed using the CLC Main Workbench Version 7.7.3. GoldenPiCS module sequences and backbones are listed in Additional file 2. Custom DNA oligonucleotides and gBlocks (from IDT, BE), restriction enzymes, T4 Ligase, Q5 polymerase (all from New England Biolabs, DE, or Fermentas, DE) and DNA cleanup kits (from Qiagen, DE, and Promega, DE) were used for routine cloning work.

GoldenMOCS and GoldenPiCS

Basic principle and background

Golden Gate cloning [17, 34, 35], a modular cloning system, was set up for simultaneous overexpression of multiple genes independent of the microorganism and further developed for application in P. pastoris (see Fig. 1 for a schematic overview). We termed the basic system GoldenMOCS, (Golden Gate-derived Multiple Organism Cloning System) and the subsystem specialized for application in P. pastoris was named GoldenPiCS (includes GoldenMOCS plus further developments). The system is generally comprised of three backbone (BB) levels. BB1 constructs harbor the three basic modules (promoters, coding sequences and terminators), BB2 constructs are used to assemble transcription units (promoter + CDS + terminator) and BB3 are used to further combine multiple transcription units (Fig. 1).

Golden Gate cloning employs type IIs restriction enzymes (BsaI and BpiI) which cut outside of their recognition site and enables scarless cloning, assembly of multiple DNA fragments and efficient one-pot cloning reactions (simultaneous restriction and ligation; termed Golden Gate assembly reaction). Therefore, internal BsaI and BpiI restriction sites must be removed from all modules by introducing point mutations, respecting the codon usage of the host organism (P. pastoris codon usage reported by De Schutter et al. [36]).

Fusion sites, modules and plasmids (summarized in Fig. 1 and Additional file 2)

Golden Gate cloning applies the two type IIs restriction endonucleases BsaI and BpiI, which yield four base pair overhangs outside of their recognition sequence. These overhangs - termed fusion sites (Fs) - can be freely designed and are used to systematically assemble modules in the GoldenMOCS.

Modules of the GoldenPiCS include basic modules (promoters, CDSs, terminators), resistance cassettes, integration sites, and linkers (containing restriction sites for DNA integration and excision; BB2 linkers additionally contain a 5′ located strong artificial transcriptional terminator (BBa_B1007, modified E. coli thr terminator) to prevent transcriptional read-through from the resistance gene). The following nomenclature is used for basic modules: P XXXn or pXXXn for promoters, YYYn for coding sequences and ZZZntt for terminators. Modules from other organisms are indicated by the initials of the species name, e.g. ‘Sc’ for S. cerevisiae.

Recipient BB1 and BB2 plasmids were adapted from pIDT-SMART (IDT, BE) and pSTBlue-1 (VWR, DE), respectively (with kanamycin/ampicillin resistance). All recipient backbones are comprised of an origin of replication for E. coli, a resistance cassette (for E. coli or P. pastoris, a linker with BpiI and/or BsaI cloning sites, while BB3 additionally contains a genomic locus for integration or episomal plasmid maintenance for P. pastoris.

Golden Gate assembly – BB1

The three basic modules promoter, CDS and terminator are assembled into BB1 using primers with BsaI sites and two appropriate fusion sites: Fs1-Fs2 to integrate into recipient BB1_12 (for promotor modules), Fs2-Fs3 to integrate into BB1_23 (for CDS modules) and Fs3-Fs4 to integrate into BB1_34 (for terminator modules). Multiple fragments (e.g. to introduce mutations or to create fusion genes) can be assembled in the BB1 assembly reaction by appropriate fusion site design. All inserts which were assembled into BB1 need to be checked by sequencing.

Golden Gate assembly – BB2

Single transcription units (promoter, CDS, terminator) are assembled into a recipient BB2 using the fusion sites Fs1, Fs2, Fs3 and Fs4. Depending on the intended position of the transcription unit in BB3, the appropriate BB2 is used: BB2_AB with FsA-FsB for the first, BB2_BC with FsB-FsC for the second position, etc.

Golden Gate assembly – BB3

Multiple transcription units are assembled into a recipient BB3 using fusion sites appropriate for the number of transcription units (e.g. A-C for two transcription units). For overexpression of a single transcription unit, direct cloning from BB1 into a special BB3, equipped with a BB2 linker with BpiI restriction sites and fusion sites Fs1-Fs4 (e.g. BB3aN_14) can be done.

BB3 creation

De novo assembly of BB3 plasmids can be done using a BpiI Golden Gate Assembly reaction with the following modules: linker, resistance cassette, integration locus and Ori modules - including appropriate flanking fusion sites (Fs1–2, Fs2–3, Fs3–4 and Fs4–1, respectively). In order to create recipient BB3 for direct cloning with BB1, the linker with fusion sites FsA-FsB can be replaced using a BsaI reaction with BB2_AB – thereby introducing the BB2 linker with BpiI restriction sites and fusion sites Fs1-Fs4. Amplification and sequencing primers are included in Additional file 2.

BB3 plasmids for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing were assembled as usual recipient BB3, consisting of resistance cassette, Ori, CEN/ARS locus and a linker containing fusion sites FsA-FsC for integration of two transcription units (Additional file 2 and Fig. 6).

Golden Gate assembly reaction

One μL BsaI or BpiI (10 U), 40 U T4 Ligase (0.1 μL), 2 μL CutSmart™ Buffer (10×, NEB), 2 μL ATP (10 mM, NEB) and 40 nM dilutions of PCR fragments and/or carrier and recipient backbone were diluted in 20 μL total volume and incubated as follows: 8 to 50 cycles (depending on insert number) of each 2 min at 37 °C and 16 °C, followed by 10 min at 37 °C, 30 min at 55 °C and 10 min at 80 °C (final ligation, digestion and heat inactivation).

Characterization of genetic parts in P. pastoris

For evaluation of promoter and terminator function (screening), P. pastoris transformants were cultivated at 25 °C on a rotary shaker at 280 rpm. Screening conditions were designed to represent bioreactor cultivation phases (Additional file 1: Table S2). Briefly, glycerol and glucose excess conditions (“G”, “D”) as present in batch cultivation were analyzed at a high growth rate of μMAX~0.22 and an OD600 of about 3–8. Limiting glucose (“X”, 12 mm glucose feed beads, releasing glucose at a non-linear rate of 1.63 ∙ t0.74 mg per disc, Kuhner, CH) and methanol feed (“M”), representing fed batch conditions, were measured at an OD600 of about 10 and growth rates around 0.04 h−1 and μMAX-MeOH (up to 0.1 h−1), respectively. Growth rates and biomass increase can roughly be calculated from the substrate yield coefficient, which is YX/S ~ 0.5 for μ > 0.05 h−1 on glucose [37] and YX/S ~ 0.6 on glycerol [38], while it is lower on sole methanol (YX/S ~ 0.4) and methanol culture lag phases are prolonged [39].

Flow cytometry

Analysis of eGFP levels in screenings and corresponding calculations were done as described before [40, 41]. Briefly, fluorescence intensity is related to the cell volume for all data points, resulting in specific eGFP fluorescence. Thereof, the population’s geometric mean is normalized by subtracting background signal (of non-producing P. pastoris wild type cells) and related to expression under the control of P GAP. Indel mutation screenings with CRISPR/Cas9-BB3’s were done in a CBS7435(MutS) strain stably expressing eGFP under control of the P GAP promoter (integration in the native P GAP locus). Disruption frequency of eGFP (InDel mutations) was analysed by flow cytometry and verified by sequencing of individual clones.

InDel mutations using CRISPR/Cas9

Targeting efficiency of the modular CRISPR/Cas9 system on native sequences was evaluated by disruption of the coding sequences of AOX1 and DAS1 at two different positions each. CRISPR/Cas9-BB3s plasmids harboring the Cas9/sgRNA transcription units were transformed into electro-competent P. pastoris by electroporation (2 kV, 4 ms, GenePulser, BioRad) according to [4] and selected on G418 agar plates. After restreaking the clones two times on selective agar plates the targeted loci were checked for InDel mutations by colony PCR, followed by Sanger sequencing. Sequences of gRNAs and verification primers are listed in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Additional files

File contains additional Tables S1-S3. Table S1. Gene copy numbers of four GOIs in three engineered Pichia pastoris strains after three consecutive batch cultivations. Table S2. P. pastoris deep-well screening conditions. Table S3. Selection markers. Table S4. sgRNA sequences for CRISPR/Cas9 and verification primers for InDel mutations. (PDF 277 kb)

GoldenPiCS modules and plasmids. Modules and plasmids are listed with corresponding cloning- and fusion sites and full sequences. DNA orientation is 5’to 3′. All plasmids are available at Addgene. (XLSX 33 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Diane Barbay and Franz Zehetbauer for supporting cloning work. We also thank Minoska Valli for proofreading of the manuscript. EQ-VIBT Cellular Analysis is acknowledged for providing flow cytometry equipment.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy (BMWFW), the Federal Ministry of Traffic, Innovation and Technology (bmvit), the Styrian Business Promotion Agency SFG, the Standortagentur Tirol, the Government of Lower Austria and ZIT – Technology Agency of the City of Vienna through the COMET-Funding Program managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency FFG.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated in this study are included in the article and its supplementary information files. All described genetic parts and the GoldenPiCS-vectors are available through Addgene.

Abbreviations

- BB

Backbone

- Cas9

CRISPR-associated protein 9

- CRISPR

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

- eGFP

Enhanced GFP

- Fs

Fusion site

- GCN

Gene copy number

- GGA

Golden Gate Assembly

- GOI

Gene of interest

- GoldenMOCS

Golden Gate-derived multi-organism cloning system

- GoldenPiCS

Golden Gate-derived Pichia pastoris cloning system

- InDel

Insertion or deletion mutation

- MUT

Methanol utilization

- RNAP

RNA polymerase

- sgRNA

Single guide RNA

Authors’ contributions

RP, JB, SSt, TG and RZ performed experimental work and data analyses. RP and KB supervised the experimental work and contributed to study design. HM and MS designed the initial Golden Gate parts and conceived of the cloning strategy. BG and DM contributed to study design and conceived the project. RP drafted the manuscript, BG, DM and HM revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12918-017-0492-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Roland Prielhofer, Email: roland.prielhofer@boku.ac.at.

Juan J. Barrero, Email: juanjose.barrero@uab.cat

Stefanie Steuer, Email: stefanie.steuer@kabsi.at.

Thomas Gassler, Email: thomas.gassler@boku.ac.at.

Richard Zahrl, Email: richard.zahrl@boku.ac.at.

Kristin Baumann, Email: kristin.baumann@boku.ac.at.

Michael Sauer, Email: michael.sauer@boku.ac.at.

Diethard Mattanovich, Email: diethard.mattanovich@boku.ac.at.

Brigitte Gasser, Phone: +43-1-47654-79033, Email: brigitte.gasser@boku.ac.at.

Hans Marx, Email: hans.marx@boku.ac.at.

References

- 1.Puxbaum V, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Quo vadis? The challenges of recombinant protein folding and secretion in Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(7):2925–2938. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6470-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne B. Pichia pastoris as an expression host for membrane protein structural biology. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2015, 32C:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kang Z, Huang H, Zhang Y, Du G, Chen J. Recent advances of molecular toolbox construction expand Pichia pastoris in synthetic biology applications. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33(1):19. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasser B, Prielhofer R, Marx H, Maurer M, Nocon J, Steiger M, Puxbaum V, Sauer M, Mattanovich D. Pichia pastoris: protein production host and model organism for biomedical research. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:191–208. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattanovich D, Graf A, Stadlmann J, Dragosits M, Redl A, Maurer M, Kleinheinz M, Sauer M, Altmann F, Gasser B. Genome, secretome and glucose transport highlight unique features of the protein production host Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Factories. 2009;8:29. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner JM, Alper HS. Synthetic biology and molecular genetics in non-conventional yeasts: current tools and future advances. Fungal Genet Biol. 2016;89:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwarzhans JP, Wibberg D, Winkler A, Luttermann T, Kalinowski J, Friehs K. Integration event induced changes in recombinant protein productivity in Pichia pastoris discovered by whole genome sequencing and derived vector optimization. Microb Cell Factories. 2016;15:84. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0486-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinhandl K, Winkler M, Glieder A, Camattari A. Carbon source dependent promoters in yeasts. Microb Cell Factories. 2014;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinacker D, Rabert C, Zepeda AB, Figueroa CA, Pessoa A, Farías JG. Applications of recombinant Pichia pastoris in the healthcare industry. Braz J Microbiol. 2013;44(4):1043–1048. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822013000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasser B, Steiger MG, Mattanovich D. Methanol regulated yeast promoters: production vehicles and toolbox for synthetic biology. Microb Cell Factories. 2015;14(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartner FS, Glieder A. Regulation of methanol utilisation pathway genes in yeasts. Microb Cell Factories. 2006;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogl T, Glieder A. Regulation of Pichia pastoris promoters and its consequences for protein production. New Biotechnol. 2013;30(4):385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nocon J, Steiger M, Mairinger T, Hohlweg J, Russmayer H, Hann S, Gasser B, Mattanovich D. Increasing pentose phosphate pathway flux enhances recombinant protein production in Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Delic M, Rebnegger C, Wanka F, Puxbaum V, Haberhauer-Troyer C, Hann S, Köllensperger G, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Oxidative protein folding and unfolded protein response elicit differing redox regulation in endoplasmic reticulum and cytosol of yeast. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012; 52(9):2000–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Idiris A, Tohda H, Sasaki M, Okada K, Kumagai H, Giga-Hama Y, Takegawa K. Enhanced protein secretion from multiprotease-deficient fission yeast by modification of its vacuolar protein sorting pathway. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85(3):667–677. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casini A, Storch M, Baldwin GS, Ellis T. Bricks and blueprints: methods and standards for DNA assembly. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16(9):568–576. doi: 10.1038/nrm4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obst U, TK L, Sieber V. A modular toolkit for generating Pichia pastoris secretion libraries. ACS Synth Biol. 2017;6(6):1016–1025. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schreiber C, Muller H, Birrenbach O, Klein M, Heerd D, Weidner T, Salzig D, Czermak P. A high-throughput expression screening platform to optimize the production of antimicrobial peptides. Microb Cell Factories. 2017;16(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogl T, Sturmberger L, Kickenweiz T, Wasmayer R, Schmid C, Hatzl AM, Gerstmann MA, Pitzer J, Wagner M, Thallinger GG, et al. A toolbox of diverse promoters related to methanol utilization: functionally verified parts for heterologous pathway expression in Pichia pastoris. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5(2):172–186. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber E, Engler C, Gruetzner R, Werner S, Marillonnet S. A modular cloning system for standardized assembly of multigene constructs. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarkari P, Marx H, Blumhoff ML, Mattanovich D, Sauer M, Steiger MG. An efficient tool for metabolic pathway construction and gene integration for Aspergillus niger. Bioresour Technol. 2017;245(Pt B):1327–1333. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Aw R, Polizzi KM. Can too many copies spoil the broth? Microb Cell Factories. 2013;12:128. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hohenblum H, Gasser B, Maurer M, Borth N, Mattanovich D. Effects of gene dosage, promoters, and substrates on unfolded protein stress of recombinant Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;85(4):367–375. doi: 10.1002/bit.10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasser B, Dragosits M, Mattanovich D. Engineering of biotin-prototrophy in Pichia pastoris for robust production processes. Metab Eng. 2010;12(6):573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prielhofer R, Cartwright SP, Graf AB, Valli M, Bill RM, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Pichia pastoris regulates its gene-specific response to different carbon sources at the transcriptional, rather than the translational, level. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):167. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1393-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigull J, Mnaimneh S, Pootoolal J, Robinson MD, Hughes TR. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA stability using transcription inhibitors and microarrays reveals posttranscriptional control of ribosome biogenesis factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(12):5534–5547. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5534-5547.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weninger A, Hatzl AM, Schmid C, Vogl T, Glieder A. Combinatorial optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 expression enables precision genome engineering in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. J Biotechnol. 2016;235:139–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Liachko I, Dunham MJ. An autonomously replicating sequence for use in a wide range of budding yeasts. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014;14(2):364–367. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(7):4336–4343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao Y, Zhao Y. Self-processing of ribozyme-flanked RNAs into guide RNAs in vitro and in vivo for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014;56(4):343–349. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labun K, Montague TG, Gagnon JA, Thyme SB, Valen E. CHOPCHOP v2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W272–W276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogl T, Ahmad M, Krainer FW, Schwab H, Glieder A. Restriction site free cloning (RSFC) plasmid family for seamless, sequence independent cloning in Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Factories. 2015;14:103. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engler C, Gruetzner R, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. Golden Gate shuffling: a one-pot DNA shuffling method based on type IIs restriction enzymes. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Werner S, Engler C, Weber E, Gruetzner R, Marillonnet S. Fast track assembly of multigene constructs using Golden Gate cloning and the MoClo system. Bioeng Bugs. 2012;3(1):38–43. doi: 10.4161/bbug.3.1.18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Schutter K, Lin YC, Tiels P, Van Hecke A, Glinka S, Weber-Lehmann J, Rouzé P, Van de Peer Y, Callewaert N. Genome sequence of the recombinant protein production host Pichia pastoris. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(6):561–566. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rebnegger C, Graf AB, Valli M, Steiger MG, Gasser B, Maurer M, Mattanovich D. In Pichia pastoris, growth rate regulates protein synthesis and secretion, mating and stress response. Biotechnol J. 2014;9(4):511–525. doi: 10.1002/biot.201300334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurramkonda C, Adnan A, Gabel T, Lunsdorf H, Ross A, Nemani SK, Swaminathan S, Khanna N, Rinas U. Simple high-cell density fed-batch technique for high-level recombinant protein production with Pichia pastoris: application to intracellular production of hepatitis B surface antigen. Microb Cell Factories. 2009;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jungo C, Rérat C, Marison IW, Von Stockar U: Quantitative characterization of the regulation of the synthesis of alcohol oxidase and of the expression of recombinant avidin in a Pichia pastoris Mut+ strain. 2006, 39(4):936–944.

- 40.Prielhofer R, Maurer M, Klein J, Wenger J, Kiziak C, Gasser B, Mattanovich D. Induction without methanol: novel regulated promoters enable high-level expression in Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Factories. 2013;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stadlmayr G, Mecklenbrauker A, Rothmuller M, Maurer M, Sauer M, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Identification and characterisation of novel Pichia pastoris promoters for heterologous protein production. J Biotechnol. 2010;150(4):519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.09.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346(6213):1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File contains additional Tables S1-S3. Table S1. Gene copy numbers of four GOIs in three engineered Pichia pastoris strains after three consecutive batch cultivations. Table S2. P. pastoris deep-well screening conditions. Table S3. Selection markers. Table S4. sgRNA sequences for CRISPR/Cas9 and verification primers for InDel mutations. (PDF 277 kb)

GoldenPiCS modules and plasmids. Modules and plasmids are listed with corresponding cloning- and fusion sites and full sequences. DNA orientation is 5’to 3′. All plasmids are available at Addgene. (XLSX 33 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study are included in the article and its supplementary information files. All described genetic parts and the GoldenPiCS-vectors are available through Addgene.