Abstract

TFIID is a critical component of the eukaryotic transcription pre-initiation complex (PIC) required for the recruitment of RNA Pol II to the start site of protein-coding genes. Within the PIC, TFIID’s role is to recognize and bind core promoter sequences and recruit the rest of the PIC components. Due to its size and its conformational complexity, TFIID poses a serious challenge for structural characterization. The limited amounts of purified TFIID that can be obtained by present methods of purification from endogenous sources has limited structural studies to cryo-EM visualization, which requires very small amounts of sample. Previous cryo-EM studies have shed light on how the extreme conformational flexibility of TFIID is involved in core promoter DNA binding. Recent progress in cryo-EM methodology has facilitated a parallel progress in the study of human TFIID, leading to an improvement in resolution and the identification of the structural elements in the complex directly involved in DNA interaction. While many questions remain unanswered, the present structural knowledge of human TFIID suggests a mechanism for the sequential engagement with different core promoter sequences and how it could be influenced by regulatory factors.

The regulation of transcription initiation is a primary means by which the expression of genes is controlled. In eukaryotic cells, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) carries out the transcription of protein-coding genes by reading the template DNA and synthesizing the complementary messenger RNA. However, because Pol II is not capable of differentiating the start of a gene from any other DNA sequence, initiation of Pol II transcription requires a vast assemblage of proteins called the transcription preinitiation complex (PIC) [1–3], which function to recognize the start region of a gene (i.e. the promoter), and to place the template DNA into the catalytic center of Pol II so that it can begin transcribing.

The general transcription factor TFIID is a pivotal component of the PIC, and is primarily responsible for recognizing the promoter DNA and nucleating PIC assembly [2–10]. TFIID is composed of the TATA-bind protein (TBP) and thirteen TBP-associated factors (TAFs) that comprise over 1 MDa in mass. According to the sequential PIC assembly pathway [2,3,11], TFIID first recognizes and binds to promoter DNA via sequence-specific interactions mediated by its TBP and TAF subunits. Recruitment of TFIIA stabilizes the DNA-bound state of TBP/TFIID [12]. Recruitment of Pol II is mediated by TFIIB and TFIIF, which interact with promoter DNA and TFIID [13]. The subsequent addition of TFIIE further stabilizes the PIC and allows for the recruitment of TFIIH, which mediates the opening of the promoter DNA duplex [14].

Despite its importance in coordinating transcription initiation, a detailed mechanistic understanding of TFIID’s activities remains elusive. The high degree of conformational plasticity within the TFIID architecture has largely limited structural analysis to low-resolution electron microscopy (EM) studies. However, by improving the biochemical preparation of TFIID complexes and by exploiting the latest technological advances within the field of 3D cryo-EM [15], we have been able to visualize promoter binding by human TFIID in close-to-atomic-level detail.

Overall architecture and flexibility of TFIID

The first low-resolution description of human TFIID using negative stain EM showed it to have a horseshoe shape defined by three lobes – A, B and C – surrounding a central cavity [16]. A similar architecture was proposed for the budding yeast complex [17], for which the use of antibody labeling led to a model of TAFs distribution within the lobes [18,19]. Early structural efforts also included studies of activator binding to human TFIID and the structural consequences of TAF isoforms [20,21]. However, it soon became clear that defining the structure of TFIID is substantially complicated by the fact that the complex is highly flexible [22,23].

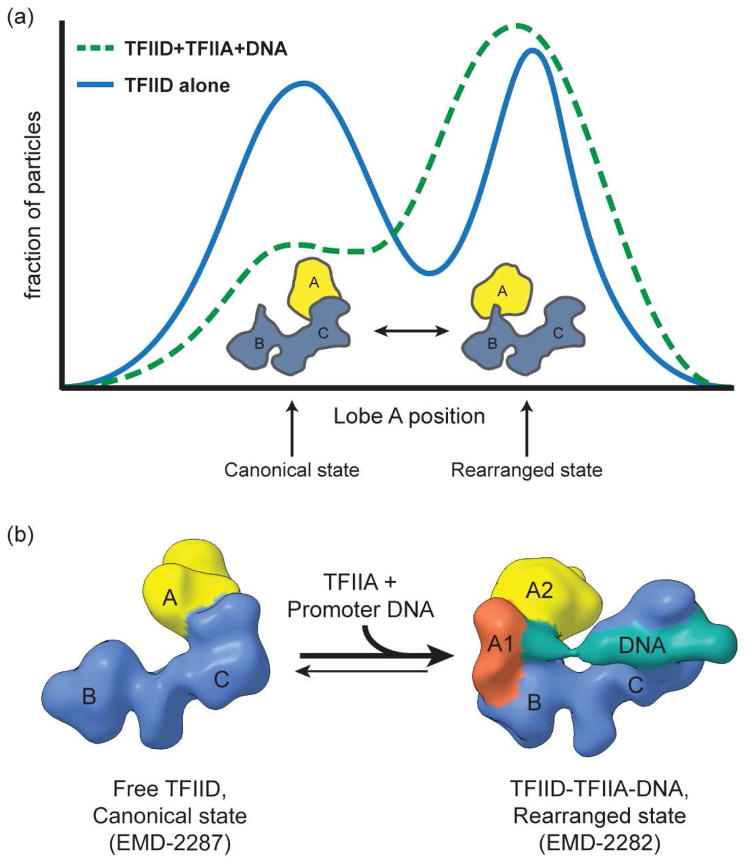

We characterized the flexibility of human TFIID and its link to promoter binding in cryo-EM studies of frozen-hydrated complexes that used computational sorting of different structural states [24]. The study demonstrated the translocation of Lobe A (corresponding to ~1/3 of the mass of TFIID) from one side of a more stable core, made up of Lobes B and C, to the other - a movement of over 100 Å. Analysis of the position of Lobe A revealed a continuous distribution between two more abundant states, that we termed “canonical” and “rearranged”. In the canonical state Lobe A is in contact with Lobe C, while in the rearranged state Lobe A is in contact with Lobe B (Figure 1a). Importantly, Lobe A stays tethered during this transition, without ever fully detaching from the rest of the complex. The study showed that in the presence of TFIIA and promoter DNA, TFIID shifts towards the rearranged state. In fact, a comparison of 3D cryo-EM reconstructions of the states present in samples of TFIID alone versus those in samples of TFIID in the presence of TFIIA and promoter DNA showed that TFIID binds promoter DNA only in the rearranged state [24] (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Conformational flexibility of TFIID and its role in promoter binding.

(a) The distribution of conformational states within cryo-EM samples of TFIID was determined by two-dimensional classification of single particle images [24]. The plots illustrate the fraction of particles with a given position of lobe A with respect to the immobile BC core, with positions to the left of center representing the canonical conformation of TFIID, in which lobe A is near lobe C, and those to the right representing the rearranged state of TFIID, in which lobe A is near lobe B. The plot for samples containing TFIID alone reveals a continuous bimodal distribution of states, with a nearly equal number of particles being in either of the two major states. In the presence of TFIIA and super core promoter DNA, however, the distribution shifts towards the rearranged state. (b) Cryo-EM 3D reconstructions of TFIID in the canonical (left) and rearranged (right) states were generated using a multi-model refinement strategy [24]. The density corresponding to the BC core (blue) stays relatively consistent between the two states, whereas the density for lobe A (yellow) moves from one side of the BC core to the other. An additional density corresponding to the promoter DNA (green) was observed only in the rearranged state reconstruction, indicating that TFIID binds DNA in the rearranged state. Later cryo-EM studies found that in the DNA-bound state, lobe A is divided into two regions – a smaller region that contains TFIIA and TBP (A1, orange), and a larger, more flexible lobe corresponding to the “core” of lobe A (A2, yellow).

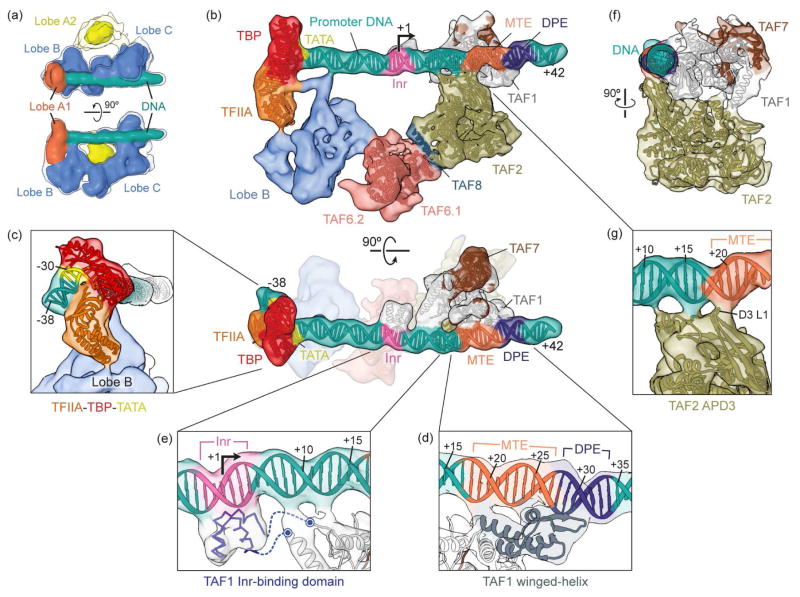

In our recent studies of TFIID’s interaction with core promoter, we assembled TFIID-TFIIA complexes onto super core promoter (SCP) DNA that was immobilized onto magnetic beads, and then eluted assembled complexes via restriction digest after washing away excess proteins. This purified promoter-bound TFIID-IIA complex was then used for cryo EM imaging using a direct electron detector [25]. After selection of the most stable complexes with the best-defined structural features, we used about 60,000 single particle images to calculate a 3D reconstruction of the complex. The overall cryo-EM 3D reconstruction of the TFIID-IIA-SCP complex shows a similar trilobed structure as previous studies, with the rigid BC core binding downstream promoter DNA and the flexible lobe A separated into a more stable fragment bound to the upstream DNA (lobe A1) and a highly flexible lobe (A2) (Figure 2a). Local resolution analysis indicated that lobe C and bound downstream promoter DNA are more ordered than lobes B and A1. Further classification of the images showed that the lobes A1 and B, together with part of the promoter, flex with respect to the rest of the complex, likely indicative of tension upon promoter binding. Following a focused refinement scheme we were able to progressively improve the map quality in the more ordered regions of the complex [15]. Lobe A1 could be unambiguously identified as corresponding to TBP-TFIIA-TATA DNA subcomplex by rigid body docking of the crystal structure, revealing that TFIIA interacts with lobe B to position TBP on the upstream promoter DNA (Figure 2b and c). The positioning of the bent TATA region defined the location of the rest of the SCP motifs along the density ascribed to DNA and showed that all promoter motifs within the SCP (TATA, Inr, MTE, and DPE) are stably contacted by subunits of TFIID (Figure 2b). The highest resolution (~8 Å) was obtained for lobe C as it engages the downstream DNA.

Figure 2. Structure of the TFIID-TFIIA-promoter complex.

(a) Low resolution reconstruction of the full purified TFIID-IIA–SCP complex [25**] showing the distribution of TFIID’s main lobes (A1, A2, B, and C) with respect to the promoter DNA (green). Isosurfaces are displayed at two thresholds, with the lower one shown in transparency to enable visualization of weaker densities. (b) Two orthogonal views of the reconstruction of the promoter-bound core of TFIID generated by refining within a mask that excluded the large and flexible lobe A2 [25**]. Fitting of atomic models shows the extensive contacts mediated by TAF1 and TAF2 with the downstream promoter DNA, while TFIIA interacts with lobe B of TFIID to situate TBP on the TATA-containing upstream promoter. Two copies of the TAF6 heat repeat (TAF6.1 and TAF6.2) form a homodimer that bridges lobe B, TFIIA, and TBP at the upstream promoter region, with TAF2, TAF1, and TAF7 at the downstream promoter region, while a helix of TAF8 likely mediates the interaction between TAF2 and one copy of TAF6. All promoter numberings are relative to the transcription start site (+1), the location and direction of which are indicated by an arrow. (c) Close-up view of the TFIIA-TBP-TATA subcomplex fitted into lobe A1 and adjacent to lobe B. (d) Close-up of the TAF1 winged-helix (WH) domain (grey) forming major interactions with the MTE and DPE promoter sequences. (e) Predicted three-dimensional structure for the TAF1 segment spanning residues 1013–1057 (blue), which is missing in the crystal structure, docked into the protein density bound to the Inr promoter sequence. The predicted unstructured linker regions that connect this Inr-binding domain with the rest of TAF1 are represented as dashed lines. (f) Side view of the TAF1-TAF7-TAF2-DNA complex, rotated 90 degrees relative to the top panel in b. (g) Close-up of the interactions between domain 3 of the TAF2 aminopeptidase-like domain (APD3) and the downstream promoter DNA, including part of the MTE sequence. The main interaction with the MTE is made by the first loop of the domain (D3 L1), which contains several highly conserved positively charged residues.

Subunit composition of Lobe C and DNA binding

The crystal structure of a human TAF1-TAF7 subcomplex [26] could be unambiguously docked into the locally-refined lobe C density, revealing that TAF1 is the primary mediator of promoter interactions within TFIID, making several promoter contacts over a ~35 bp span of promoter DNA (Figure 2b). The TAF1 WH domain forms a major interaction at the junction of the MTE and DPE promoter motifs (Figure 2d). Multiple conserved positively charged residues appear to be important for this interaction. Superposition of the TAF1 WH–DNA complex with other DNA-binding WH proteins confirms that it shares a common mode of DNA recognition. An insertion between 993–1075 of TFIID is not present in the crystal structure but appears to form a small helical domain that binds the Inr sequence (Figure 2e).

An atomic model for TAF2, based on its homology to type M1 aminopeptidases [27], could be fitted into the cryo-EM density adjacent to TAF1 and downstream promoter DNA (Figure 2b). The model shows that TAF2 interacts with TAF1 (Figure 2f) and makes additional promoter contacts using conserved loops that contain positively-charged residues (Figure 2g). In all, the footprint of TFIID spans ~70 bp of promoter DNA, with TBP and an unidentified TAF contacting the upstream promoter and including the TATA box, and with TAF1 and TAF2 contacting the downstream DNA including the Inr, MTE, and DPE motifs (Figure 2b). Fitting of the HEAT domain of TAF6 [28] revealed that it forms a homodimer that bridges lobes B and C of TFIID (Figure 2b). Finally, putative localization of the TAF2-interacting domain of TAF8 suggests that TAF8 bridges TAF6 and TAF2 (Figure 2b) [25].

Proposed model for promoter binding by TFIID and regulation thereof

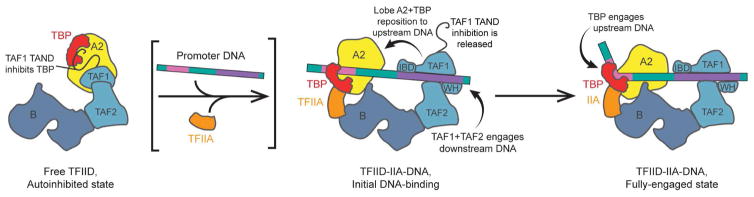

Based on existing structural studies of human TFIID, either by itself or in the presence of SCP DNA and TFIIA [24][25], we propose a possible process for the engagement of TFIID with promoter DNA, especially in cases of strong downstream promoter sequences. In free TFIID, lobe A is primarily positioned next to TAF1 within lobe C, and TBP is presumably inhibited from DNA binding by the TAND of TAF1 [29] (Figure 3, left). We speculate that this mechanism of auto-inhibition within TFIID is important for counteracting the tendency of TBP to engage DNA non-specifically, thereby reducing levels of aberrant transcription initiation. The large-scale repositioning of lobe A from lobe C to lobe B is induced or facilitated by the sequence-specific binding of TAF1/TAF2 to the downstream promoter DNA [25] (Figure 3, middle). TFIIA then localizes TBP to the upstream DNA through its interactions with lobe B and also competes with the TAF1 TAND for an overlapping binding surface on TBP, thus aiding in releasing the inhibitory effect of the TAND and freeing up TBP for DNA binding [29]. TBP is then able to engage the upstream promoter DNA in a stable, bent conformation and stabilize the TFIID-promoter complex (Figure 3, right).

Figure 3. Model for the promoter binding mechanism of TFIID.

On the left, TFIID is in the auto-inhibited canonical state, in which TBP is blocked from binding DNA by the TAND of TAF1. Interactions with promoter DNA and TFIIA (noted with the brackets) collectively repress the inhibitory effect of TAF1 and drive TFIID into the rearranged state (middle), bringing TBP toward lobe B of TFIID. Interactions with the promoter are probably initiated by TAF1 (including its winged-helix, WH, and Inr-binding domain, IBD) and TAF2 in the downstream promoter region, placing the upstream promoter DNA near lobe B, in position to be engaged by TBP. After TBP is loaded onto the promoter at the correct location, it fully engages to form the stable TBP-bent DNA complex (right).

Importantly, it has been reported that most human promoters (>80%) lack a canonical TATA sequence that would otherwise define a strict TBP-binding site [30]. Therefore, for the majority of promoters, the binding site of TBP on the upstream promoter is primarily determined by the initial specific binding of TFIID on the downstream promoter and the length of TFIID’s BC core. Accurate loading of TBP onto the core promoter is important as it in turn determines the placement of Pol II with respect to the transcription start site.

The proposed mechanism for promoter binding in eukaryotes is seemingly complex, especially considering that the prokaryotic transcription initiation process requires a single protein (sigma factor) for accurate promoter recognition and loading of the RNA polymerase. We posit that the stepwise promoter binding mechanism of TFIID, enabled by the plasticity and modularity of the complex, allows for additional points of regulation during transcription initiation. For instance, transcriptional activators interacting with TFIID at specific promoters could promote the rearranged state of the complex and thereby enhance the rate of TBP loading onto the promoter. Additionally, variation of the combination and strengths of TFIID-binding sites within the core promoter is likely to have a significant impact on the overall efficiency of TBP binding, and thus PIC assembly, on the gene-specific level.

Proposed model for TFIID interaction with the rest of the PIC

Our lab developed a reconstitution system that allowed the purification of active, homogenous human PIC assembly intermediates, in which TBP substituted for TFIID, for cryo-EM studies that aimed to directly localize each general transcription factor (GTF) within the full assembly [31]. More recently, making use of technical advances in cryo-EM, we have reported high-resolution structures of the human PICs in different functional states and the Cramer lab has reported similar high-resolution structures for the yeast PIC states [32,33].

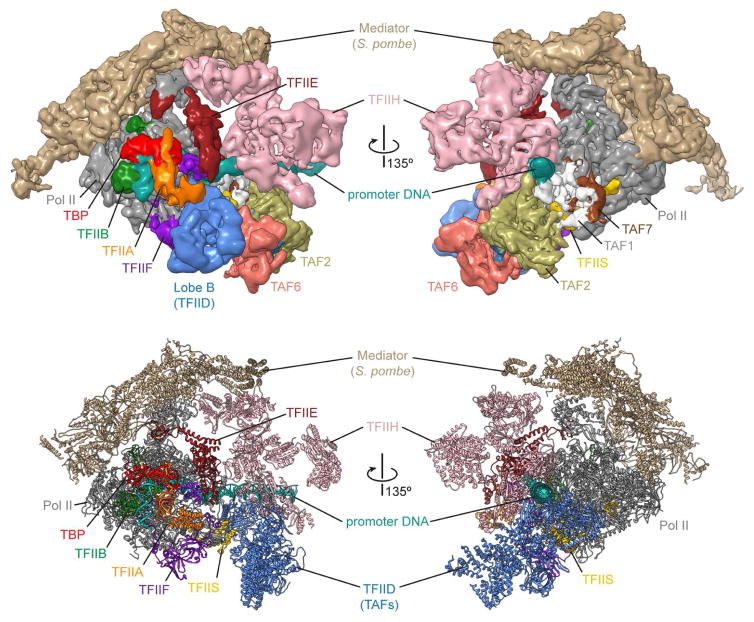

While there is no experimental structure of a TFIID-based PIC yet, it became possible to generate a “synthetic” model based on the superposition of the common elements between the TBP-based PIC and the TFIID-TFIIA-DNA structures (i.e. TBP, TFIIA and TATA box DNA) (Figure 4). The resulting model shows an overall complementarity. In this proposed structure, the lobe B of TFIID is well positioned to make contact with TFIIF and TFIIE, in agreement with previous biochemical studies [34–36]. These interactions would suggest that TAFs have a direct role in PIC assembly. The apparent minor clash between the RBP5 Pol II subunit and the promoter-bound TAF1 suggest that a structural reorganization must occur prior to promoter engagement by Pol II. This proposal agrees with time-course DNA footprinting analysis showing a structural isomerization following the addition of Pol II-TFIIB-TFIIF to the promoter-bound TFIID-TFIIA complex [37].

Figure 4. Structural model of the TFIID-based PIC.

This model was generated by superposition of the common elements of three different cryo-EM structures – the human TFIID-TFIIA-promoter complex [25**], the human TBP-based PIC (including TBP, TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIIF, TFIIS, TFIIE, TFIIH, and Pol II) [32**], and the Mediator-Pol II complex from Schizosaccharomyces pombe [40**]. The resulting model represents an ~3 MDa transcription initiation supracomplex including TFIID, TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIIF, TFIIS, TFIIE, TFIIH, Pol II, and the Mediator coactivator complex. Cryo-EM reconstructions are shown at the top, while the atomic models generated from each map are displayed at the bottom in ribbon representation.

Recent cryo-EM studies using budding or fission yeast proteins have visualized the interaction of a partial or full TBP-based PIC with the large Mediator complex involved in gene-specific activation of transcription [38–40]. Those studies have shed light on Mediator’s role in PIC stabilization and recruitment. By comparing those structures with our synthetic structure of the TFIID-based PIC leads to a model of how TFIID and Mediator surround Pol II during transcription initiation (Figure 4).

Concluding Remarks

Our high-resolution structures have revealed which components of human TFIID are involved in direct recognition of conserved core promoter sequences, and show how TFIID fulfills its primary function of properly positioning TBP on the core promoter, which ultimately determines the placement of Pol II relative to the transcription start site. We propose a major role for TFIID in providing additional levels of control during transcription initiation. The demonstrated flexible character of TFIID is likely to be an important property that allows sequential conformational states that move forward the PIC assembly and transcription initiation process.

By superimposing the structure of promoter-bound TFIID with the structures of other transcriptional assemblies, we have gained further insights into the role of TFIID in PIC assembly, such as how TFIID provides protein-protein contacts for the recruitment of other PIC components. Ultimately, these structures provide a framework for a molecular understanding of the complex mechanism underlying TFIID function, shedding new light into the overlapping roles of TFIID as both a coactivator and a general platform for PIC assembly in the coordination of transcription initiation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIGMS (GM63072 to EN). EN is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matsui T, Segall J, Weil PA, Roeder RG. Multiple factors required for accurate initiation of transcription by purified RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11992–11996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roeder RG. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodrich JA, Cutler G, Tjian R. Contacts in context: promoter specificity and macromolecular interactions in transcription. Cell. 1996;84:825–830. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MC, Chiang CM. The general transcription machinery and general cofactors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;41:105–178. doi: 10.1080/10409230600648736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burley SK, Roeder RG. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albright SR, Tjian R. TAFs revisited: more data reveal new twists and confirm old ideas. Gene. 2000;242:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verrijzer CP, Chen JL, Yokomori K, Tjian R. Binding of TAFs to core elements directs promoter selectivity by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1995;81:1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke TW, Kadonaga JT. The downstream core promoter element, DPE, is conserved from Drosophila to humans and is recognized by TAFII60 of Drosophila. Genes and Development. 1997;11:3020–3031. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DH, Gershenzon N, Gupta M, Ioshikhes IP, Reinberg D, Lewis BA. Functional characterization of core promoter elements: the downstream core element is recognized by TAF1. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9674–9686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9674-9686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu SY, Chiang CM. TATA-binding protein-associated factors enhance the recruitment of RNA polymerase II by transcriptional activators. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34235–34243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Guarente L, Sharp PA. Five intermediate complexes in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1989;56:549–561. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortes P, Flores O, Reinberg D. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: purification and analysis of transcription factor IIA and identification of transcription factor IIJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:413–421. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flores O, Lu H, Killeen M, Greenblatt J, Burton ZF, Reinberg D. The small subunit of transcription factor IIF recruits RNA polymerase II into the preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:9999–10003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holstege FC, van der Vliet PC, Timmers HT. Opening of an RNA polymerase II promoter occurs in two distinct steps and requires the basal transcription factors IIE and IIH. EMBO J. 1996;15:1666–1677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nogales E, Louder RK, He Y. Cryo-EM in the study of challenging systems: the human transcription pre-initiation complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2016;40:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andel F, Ladurner AG, Inouye C, Tjian R, Nogales E. Three-dimensional structure of the human TFIID-IIA-IIB complex. Science. 1999;286:2153–2156. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand M, Leurent C, Mallouh V, Tora L, Schultz P. Three-dimensional structures of the TAFII-containing complexes TFIID and TFTC. Science. 1999;286:2151–2153. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leurent C, Sanders S, Ruhlmann C, Mallouh V, Weil PA, Kirschner DB, Tora L, Schultz P. Mapping histone fold TAFs within yeast TFIID. Embo J. 2002;21:3424–3433. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leurent C, Sanders SL, Demeny MA, Garbett KA, Ruhlmann C, Weil PA, Tora L, Schultz P. Mapping key functional sites within yeast TFIID. Embo J. 2004;23:719–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu WL, Coleman RA, Grob P, King DS, Florens L, Washburn MP, Geles KG, Yang JL, Ramey V, Nogales E, et al. Structural changes in TAF4b-TFIID correlate with promoter selectivity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu WL, Coleman RA, Ma E, Grob P, Yang JL, Zhang Y, Dailey G, Nogales E, Tjian R. Structures of three distinct activator-TFIID complexes. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1510–1521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1790709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grob P, Cruse MJ, Inouye C, Peris M, Penczek PA, Tjian R, Nogales E. Cryo-electron microscopy studies of human TFIID: conformational breathing in the integration of gene regulatory cues. Structure. 2006;14:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papai G, Tripathi MK, Ruhlmann C, Werten S, Crucifix C, Weil PA, Schultz P. Mapping the initiator binding Taf2 subunit in the structure of hydrated yeast TFIID. Structure. 2009;17:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cianfrocco MA, Kassavetis GA, Grob P, Fang J, Juven-Gershon T, Kadonaga JT, Nogales E. Human TFIID binds to core promoter DNA in a reorganized structural state. Cell. 2013;152:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **25.Louder RK, He Y, Lopez-Blanco JR, Fang J, Chacon P, Nogales E. Structure of promoter-bound TFIID and model of human pre-initiation complex assembly. Nature. 2016;531:604–609. doi: 10.1038/nature17394. A subnanometer cryo-EM reconstuction of the human TFIID-IIA complex bound to promoter DNA showing for the first time which TAF components recognize promoter DNA. Superposion of that structure with the a TAF-less PIC reconstruction of Pol II II engaged with the rest of the GTFs led to a “synthetic” model of the full TFIID-based PIC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Curran EC, Hinds TR, Wang EH, Zheng N. Crystal structure of a TAF1-TAF7 complex in human transcription factor IID reveals a promoter binding module. Cell Res. 2014;24:1433–1444. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochan G, Krojer T, Harvey D, Fischer R, Chen L, Vollmar M, von Delft F, Kavanagh KL, Brown MA, Bowness P, et al. Crystal structures of the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase-1 (ERAP1) reveal the molecular basis for N-terminal peptide trimming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7745–7750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101262108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheer E, Delbac F, Tora L, Moras D, Romier C. TFIID TAF6-TAF9 complex formation involves the HEAT repeat-containing C-terminal domain of TAF6 and is modulated by TAF5 protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27580–27592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.379206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokubo T, Swanson MJ, Nishikawa JI, Hinnebusch AG, Nakatani Y. The yeast TAF145 inhibitory domain and TFIIA competitively bind to TATA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1003–1012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.FitzGerald PC, Shlyakhtenko A, Mir AA, Vinson C. Clustering of DNA sequences in human promoters. Genome Res. 2004;14:1562–1574. doi: 10.1101/gr.1953904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y, Fang J, Taatjes DJ, Nogales E. Structural visualization of key steps in human transcription initiation. Nature. 2013;495:481–486. doi: 10.1038/nature11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **32.He Y, Yan C, Fang J, Inouye C, Tjian R, Ivanov I, Nogales E. Near-atomic resolution visualization of human transcription promoter opening. Nature. 2016;533:359–365. doi: 10.1038/nature17970. Near atomic reconstructions of the fully assembled human TBP-based PIC in four different states showing the mechanism of promoter opening and the earliest stages of RNA transcription. The study included a model of the TFIIH subunit architexture as it engages promoter DNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Plaschka C, Hantsche M, Dienemann C, Burzinski C, Plitzko J, Cramer P. Transcription initiation complex structures elucidate DNA opening. Nature. 2016;533:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature17990. Near atomic reconstrunctions of the yeast TBP-based PIC up to TFIIE. In this work it was shown how promoter opening can occur independent of TFIIH with the additon of TFIIE and DNA binding energy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hisatake K, Ohta T, Takada R, Guermah M, Horikoshi M, Nakatani Y, Roeder RG. Evolutionary conservation of human TATA-binding-polypeptide-associated factors TAFII31 and TAFII80 and interactions of TAFII80 with other TAFs and with general transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8195–8199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruppert S, Tjian R. Human TAFII250 interacts with RAP74: implications for RNA polymerase II initiation. Genes and Development. 1995;9:2747–2755. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubrovskaya V, Lavigne AC, Davidson I, Acker J, Staub A, Tora L. Distinct domains of hTAFII100 are required for functional interaction with transcription factor TFIIF beta (RAP30) and incorporation into the TFIID complex. EMBO J. 1996;15:3702–3712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yakovchuk P, Gilman B, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. RNA polymerase II and TAFs undergo a slow isomerization after the polymerase is recruited to promoter-bound TFIID. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Plaschka C, Lariviere L, Wenzeck L, Seizl M, Hemann M, Tegunov D, Petrotchenko EV, Borchers CH, Baumeister W, Herzog F, et al. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II-Mediator core initiation complex. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14229. Cryo-EM structures of the yeast core mediator bound to a partial PIC showing binding of around the Pol II stalk. The head module was shown to interact with the Pol II dock and with the TFIIB ribbon, and thus proposed to stabilize the initiation complex. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **39.Robinson PJ, Trnka MJ, Bushnell DA, Davis RE, Mattei PJ, Burlingame AL, Kornberg RD. Structure of a Complete Mediator-RNA Polymerase II Pre-Initiation Complex. Cell. 2016;166:1411–1422 e1416. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.050. Cryo-EM and crosslinking mass spectrometry analysis of a yeast mediator-based PIC. The authors proposed a model for how TFIIK (TFIIH CAK domain) is stabilized by Mediator and how this leads to phosphorylation of the CTD. In turn, this phosphorylation disrupts CTD interaction with Mediator and allows promoter clearance by Pol II. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **40.Tsai KL, Yu X, Gopalan S, Chao TC, Zhang Y, Florens L, Washburn MP, Murakami K, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, et al. Mediator structure and rearrangements required for holoenzyme formation. Nature. 2017;544:196–201. doi: 10.1038/nature21393. A near atomic reconstruction of the yeast Mediator as it binds to Pol II, showing the strucutral rearangements within Mediator that need to occur to bind the polymerase. The authors proposed a model for Pol II loading where the CTD first binds Mediator, leading to subsequent Pol II association and formation of the holoenzyme. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]