1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Barriers of the Central nervous system

The brain and retinal tissues are the highest energy-demanding systems in the body, because of neuronal activity. With 2% of the total body mass, the brain consumes 20% of the basal metabolic rate (Clarke DD 1999), while 8% is consumed by retina (Howard, Blakeslee et al. 1987, Niven and Laughlin 2008). The endothelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-retinal barrier (BRB), provide enough oxygen and glucose for neuronal function while restricting the flux of other molecules and cells in order to protect the neuronal environment. The specific characteristics of the vasculature in these tissues provide the basis of a barrier function as described in this review.

In 1885, Paul Ehrlich published the first observations of a Central Nervous System (CNS) barrier. Ehrlich observed that water-soluble dyes injected subcutaneously stained all organs except the brain and spinal cord (Ehrlich 1885). But it wasn’t until 1900, when the concept of a CNS barrier was introduced by Lewandosky who termed it “capillary wall”, and by Lina Stern in 1918, who introduced the terminology “barrier” (Saunders, Dreifuss et al. 2014). The pioneering work performed by Ehrlich, Lewandosky, Stern and other scientists led to the recognition of the BBB.

Similarly, Schnaudigel in 1913 and Palm in 1947, recognized the BRB using intravenously injected trypan blue that stained all organs of rabbits with the exception of the CNS, including the retinal tissue (Palm 1947), which was further supported at the ultrastructural level by Cunha-Vaz et al. (Cunha-Vaz, Shakib et al. 1966, Shakib and Cunha-Vaz 1966). Thus, the BBB and the BRB form part of the barriers of the CNS. We now understand that the BBB and BRB provide tight control of the neuronal environment regulating the flux of blood borne material into the neural parenchyma. These barriers maintain proper neural homeostasis and protect the neural tissue from potential blood borne toxicity.

1.2. Blood-Retinal Barrier

Structurally, the BRB is composed of two distinct barriers; the outer BRB (oBRB), consisting of retinal pigment epithelium that regulates transport between the choriocapillaris and the retina, and the inner BRB (iBRB), which regulates transport across retinal capillaries. Loss of the iBRB contributes to the pathophysiology of a number of retinal diseases including diabetic retinopathy (Frey and Antonetti 2011). This review will first describe the basis of the iBRB and routes of transport across retinal endothelial cells. Changes in barrier properties during diabetes and other blinding diseases will be discussed and the review will end with novel insight into factors that regulate development of the barrier.

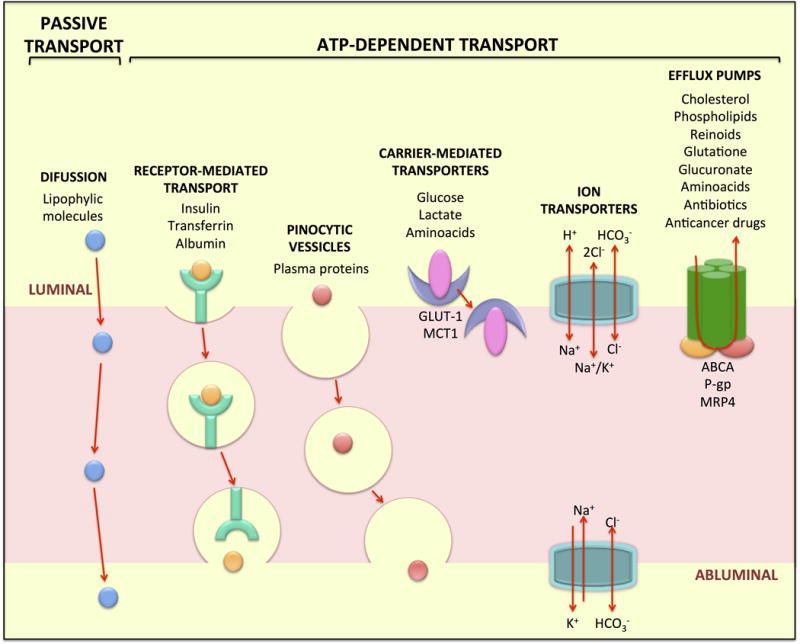

2. FLUX ACROSS THE iBRB

The CNS barriers are not absolute barriers that block all transport across the endothelium. Instead, the CNS barriers are highly selective barriers that regulate the movement of ions, water, solutes and cells, across the vascular bed. Flux of a solute or water, describes the net movement over time across a barrier, while permeability describes the property of the barrier, in this case, of the iBRB. Changes in permeability across the vascular bed may occur through changes in transport across the cells, broadly termed transcytosis, or through changes in the junctional complex connecting cells, leading to flux around the cells or paracellular permeability. Both transcellular and paracellular routes are composed of multiple specific pathways that may act simultaneously and are not mutually exclusive, and collectively contribute to altered flux.

2.1. Transcytosis

In 1960, Dr. Palade et al. described invaginations of the plasmalemma in the capillary endothelium that “pinch off” from the surface and form intracellular vesicles (Palade 1960). The electron microscopy techniques at the time allowed detection of intracellular vesicles and invaginations, that suggested a regulated and directional transport (Palade and Bruns 1968). In addition, some groups have observed a preference of localization of vesicles, suggesting a unidirectional flow (Hofman, Hoyng et al. 2001). However, this idea has been challenged since recent studies showed invaginations at both sides (Chow and Gu 2017).

In 1979, Nicolae Simionescu introduced the term transcytosis. In his electron microscopy studies, he identified the appearance of highly dense structures that he called specialized plasmalemma vesicles within endothelial cells. We now know that transcellular transport across retinal endothelial cells is necessary for regulation of the retinal environment’s homeostasis.

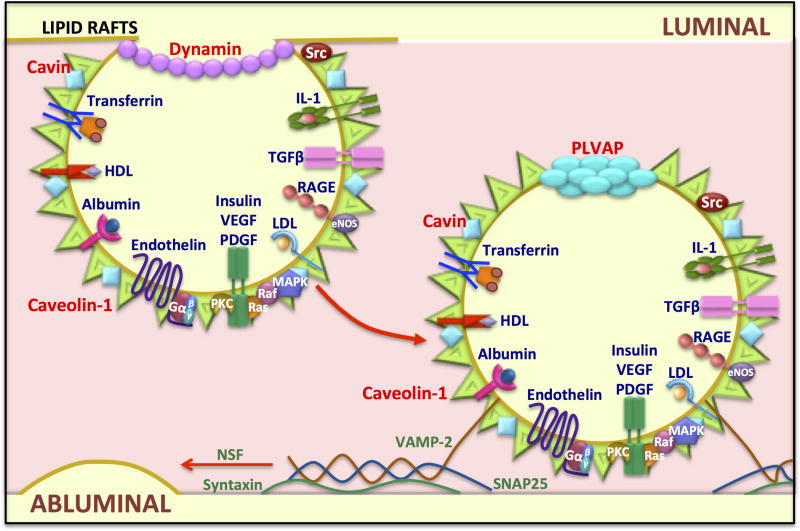

There are a variety of routes that make up the transcellular route (Klaassen, Van Noorden et al. 2013). Some small lipophilic molecules are able to passively diffuse along the retinal endothelial membrane and cross the BRB (Toda, Kawazu et al. 2011). Other, larger lipophilic molecules and hydrophilic molecules require ATP-dependent processes to cross the barrier including; receptor mediated vesicular transport, non-receptor mediated pinocytosis, transporters and pumps (Figure 1). Brain and retinal endothelial cells selectively regulate the transcellular movement of molecules from the blood to the neural tissue by controlling the expression of molecules at both, luminal and abluminal sides. Retinal endothelial cells express a low number of receptors, transporters and vesicle formation mediators, in combination with a high expression of efflux pumps (Sagaties, Raviola et al. 1987), which collectively contributes to the BRB.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of transcellular transport across retinal endothelial cells.

Some molecules can cross by diffusion due to their lipophilic properties. Other transport mechanisms are energy-dependent processes and include receptor-mediated transport, pinocytic vesicles, carrier-mediated transporters, ion transporters and efflux pumps. The endothelial cells that constitute the BRB, express a low number of these transporter mechanisms, some of the most important are indicated.

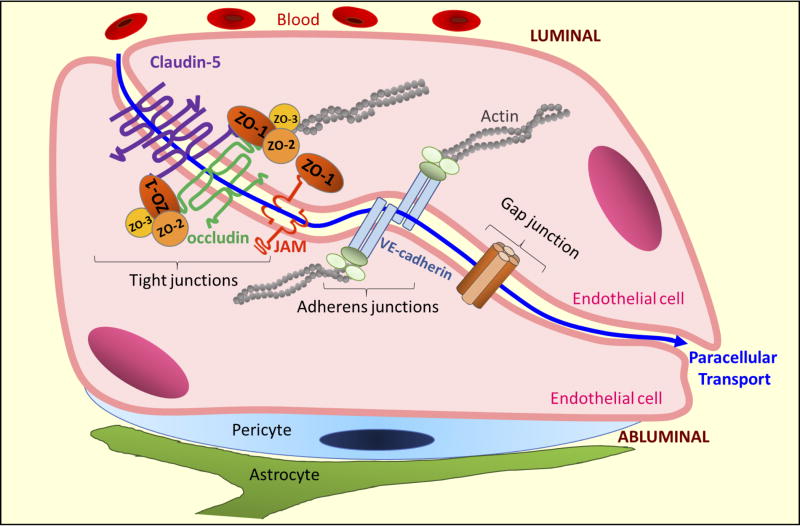

2.1.1. Caveolae

After the discovery of caveolin-1, the structural molecular component of plasmalemma vesicles (Glenney and Soppet 1992, Kurzchalia, Dupree et al. 1992, Rothberg, Heuser et al. 1992), the vesicles were re-named caveolae. Caveolae appear as an electron dense structure by electron microscopy, due to the lipid rafts enriched in glycosphingolipids, sphingomyelin, cholesterol and lipoproteins. In addition to caveolin-1, cavin protein also covers caveolae surface and promotes vesicle stabilization at the plasma membrane (Vinten, Johnsen et al. 2005, Hill, Bastiani et al. 2008, Liu and Pilch 2008). Caveolae vesicles also contain receptors for: transferrin, insulin, albumin, advanced glycation end products, low- and high- density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL and HDL, respectively), interleukin 1, endothelin, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). Further, the vesicles also contain signal transduction molecules including small G-proteins, MAP kinases, Src kinases, Raf and PKC (Patel, Murray et al. 2008, Insel and Patel 2009) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Molecular mechanisms in caveolae-mediated transport.

Caveolae are lipid rafts or membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol that promote the clustering of molecules at the membrane. Caveolin-1 is enriched in these domains and caveolae are responsible for vesicle dependent transport in endothelial cells. Other molecules involved in caveolae formation and transcytosis are indicated in red. Caveolae vesicles also contain receptors (blue) and signaling molecules (white) that can transduce an external signal to the cell interior. Caveolae are able to recycle to the luminal membrane or to regulate transport to the abluminal membrane. Finally, vesicle fusion proteins (green) including the SNAREs VAMP-2 and SNAP25, regulate fusion to the membrane.

The process of endocytosis of caveolae has been described in some molecular detail. During the invagination process, Src kinase phosphorylates dynamin and promotes its recruitment at the neck of the vesicles, controlling the vesicle closure and delivery to the cytoplasm (Oh, McIntosh et al. 1998). Then, the plasmalemma vesicle associated protein (PLVAP), also known as PAL-E antigen of PV-1, forms a cap on the vesicle. In the cytoplasm, caveolae vesicles are able to transduce signals, to be recycled to the same side of the membrane where they were formed, or move to the opposite membrane in order to deliver their content. Then, the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor, or SNARE proteins regulates the vesicle fusion into the plasma membrane. VAMP-2 is a SNARE protein in vesicles that binds to paxin, syntaxin and SNAP25, the SNAREs at the target membrane, while N-ethymaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) is required for the final fusion by disassembling the SNARE complex (Mehta and Malik 2006, Lang 2007) (Figure 2).

In retinal endothelial cells, vesicle transport is low in comparison with non-barrier endothelia; however, it has been shown that VEGF-induced permeability is regulated though an increased vesicular transport in vitro (Feng, Venema et al. 1999) and in vivo (Hofman, Blaauwgeers et al. 2000). Likewise, in a model of autoimmune uveoretinitis (Lightman and Greenwood 1992) and in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (Gardiner, Stitt et al. 1995), an increase of transcytosis was observed, as assessed with horse radish peroxidase staining, suggesting that the transcytosis rate increases in pathological conditions. A recent publication reveals that knockdown of PLVAP can reduce or prevent VEGF induced permeability to multiple molecules across endothelial monolayers (Wisniewska-Kruk, van der Wijk et al. 2016) suggesting a required role in VEGF-altered permeability.

Caveolin KO mice provide evidence for a role of transcytosis in endothelial permeability. The KO mice are viable and fertile, but with vascular dysfunctions like impaired nitric oxide (NO) and calcium signaling (Drab, Verkade et al. 2001, Razani, Engelman et al. 2001). As expected, mice deficient in caveolin-1 showed less flux across various endothelia; however, this seems to be compensated by an increase in the paracellular transport of albumin (Schubert, Frank et al. 2001, Schubert, Frank et al. 2002). These studies suggest mechanisms that may connect paracellular and transcellular flux leading to some homeostasis in transport. It should be noted, however, that given the broader role of caveolae in signaling and the role of vesicular movement in tight junction regulation, discussed below, the results of caveolae KO mice may not be directly or solely due to changes in transcytosis.

Some studies suggest that caveolae might regulate both, transcellular and paracellular transports. The tight junction complex co-localize with caveolin-1 at cholesterol-enriched regions (Nusrat, Parkos et al. 2000). Further, in an in vitro model of BBB, the knock down of caveolin-1 induces the dissociation of occludin, VE-Cadherin and β-catenin from the cytoskeleton, in combination with an increase of permeability (Song, Ge et al. 2007). Since caveolae can also regulate endocytosis, cholesterol levels and signal transduction (Anderson 1993, Lisanti, Scherer et al. 1994, Parton and Richards 2003, Milovanova, Chatterjee et al. 2008), it is possible that caveolin might also regulate tight junction endocytosis and as a consequence, paracellular transport. Understanding the time dependent relationship of transcellular and paracellular flux as well as molecular specific routes may shed novel insight into the disease process of altered permeability.

2.1.2. PLVAP

PVLAP was identified as the ligand of the human endothelium-specific monoclonal antibody APL-E (Schlingemann, Dingjan et al. 1985, Niemela, Elima et al. 2005) and the mouse-specific monoclonal MECA-32 (Hallmann, Mayer et al. 1995). Its expression in brain and retinal endothelial cells is absent or low, correlating with the low number of vesicles (Schlingemann, Hofman et al. 1997). In brain tumors, diabetic macular edema and VEGF-induced retinopathy, its expression increases and co-localizes with the capillary sites where the barrier is lost (Hofman, Blaauwgeers et al. 2001, Carson-Walter, Hampton et al. 2005, Wisniewska-Kruk, van der Wijk et al. 2016). In addition, VEGF can increase its expression in vitro (Strickland, Jubb et al. 2005, Klaassen, Hughes et al. 2009) and in vivo (Howard, Blakeslee et al. 1987, Hofman, Blaauwgeers et al. 2001, Klaassen, Hughes et al. 2009), supporting PVLAP as a good marker for increased transcytosis.

In vivo studies of permeability using fluorescent molecules like sulfo-NHS-biotin have shown that PLVAP is highly expressed specifically at the places of endothelial leakiness, and this expression inversely correlates with the expression of the tight junction protein claudin-5. Thus, leaky endothelial cells are PLVAP+/Claudin5−, and tight endothelial cells are PLVAP−/Claudin5+ (Zhou, Wang et al. 2014) suggesting a coordination in regulation of both transcellular and paracellular permeability.

2.1.3. Albumin

The major regulator of oncotic pressure is albumin and as such, this molecule appears to have specific mechanisms of transport across the endothelium. Retinal and brain endothelium express a selective number of albumin-binding proteins (Stewart 2000). Albumin binds to glycoproteins of 18, 30 and 60 kDa (gp18, gp30 and gp60, respectively) expressed at the luminal side of endothelial cells. The 18 and 30 kDa molecules have higher affinity for modified forms of albumin and activate signals that promote albumin degradation (Schnitzer, Sung et al. 1992, Schnitzer and Bravo 1993, Schnitzer and Oh 1994). On the other hand, non-modified albumin has more affinity for gp60, which does not induce lysosomal degradation (Vogel, Easington et al. 2001, Vogel, Minshall et al. 2001). Also, vesicles with gp60 bound albumin are capable of internalizing at the luminal side and releasing their content at the abluminal side (Ghitescu, Fixman et al. 1986, Milici, Watrous et al. 1987, Simionescu and Simionescu 1991).

By using fluorescent antibodies for gp60, it has been shown that gp60 can form caveolin-1 clusters at the plasma membrane, thus promoting albumin transcytosis (Schnitzer 1992, Tiruppathi, Song et al. 1997, Minshall, Tiruppathi et al. 2000). Moreover, activation of gp60 also promotes internalization of horse radish peroxidase, a molecule that does not have a specific receptor (Tiruppathi, Finnegan et al. 1996, Tiruppathi, Naqvi et al. 2004); and myeloperoxidase transport, a molecule that binds to some forms of albumin (Tiruppathi, Naqvi et al. 2004). This suggest a role of gp60 in the transcytosis of plasma molecules, probably though pinocytosis. Importantly, gp60-dependent transcytosis can be inhibited with lectins, agglutinin or anti-gp60 antibodies, which compete for albumin binding sites in gp60 (Schnitzer, Carley et al. 1988, Schnitzer, Carley et al. 1988, Schnitzer and Oh 1994), thus supporting the role of gp60 in transcytosis.

2.1.4. Mfsd2a

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is one of the omega-3 fatty acid essential for brain growth and function. Its uptake in the brain in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), is regulated by the major facilitator super family domain containing 2a (Mfsd2a) (Nguyen, Ma et al. 2014). Mfsd2a is selectively expressed in brain and retina capillaries, specifically at the BBB and BRB sites. It has been shown recently, that mice deleted in mfsd2a gene present microcephaly at P4, accompanied with low levels in LPC-DHA, neuronal cell loss and cognitive deficits, a phenotype that can be recapitulated in transgenic mice with a specific mutation in Mfsd2a that blocks its transporter activity (Mfsd2a D96A), indicating that Mfsd2a is required for brain development (Andreone, Chow et al. 2017). In these studies, when brain capillaries from Mfsd2a KO or Mfsd2a (D96A) mice were analyzed by electron microscopy, they showed an increased vesicle transport or transcytosis without affecting tight junctions, in addition to high rates of permeability of 10–70 kDa dextran, sulfo-NHS-biotin and HRP molecules, suggesting that Mfsd2a controls the permeability of brain capillaries in a mechanism dependent of vesicle traffic.

At a molecular level, lipidomic mass spectrometry analysis comparing barrier (brain) versus non-barrier (lung) endothelial cells, demonstrated that brain capillaries have a unique lipid composition enriched in DHA phsospholipid species that includes lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and phosphatidylserine (PS). In addition, the triglycerides (TAGs) and cholesterylester (CE) that in lung endothelial cells form intracellular lipid droplets regulated by caveolin vesicle traffic (Cohen, Razani et al. 2004, Pol, Martin et al. 2004, Martin and Parton 2005), were present at low levels in brain capillaries. Since caveolae membrane domains can be affected by lipid composition (Lingwood and Simons 2010, Parton and del Pozo 2013), specifically by DHA that displaces caveolin-1 at the membrane (Ma, Seo et al. 2004, Chen, Jump et al. 2007, Li, Zhang et al. 2007), the enrichment in DHA lipid species in brain endothelial cells reflect a specific environment inhibiting formation of caveolin vesicles, resulting in a low rate of transcytosis.

Together, these studies suggest that Mfsd2a is selectively expressed in barrier endothelial cell increase LPC-DHA uptake, controlling the lipid composition and reducing caveolae microdomains, which results in reduced transcytosis.

2.2. Paracellular transport

In addition to transcellular transport, molecules can move via the paracellular transport, which occurs through the intercellular space between adjacent cells. It is highly regulated by the formation of junctional complexes that consist of tight junctions, adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes with tight and adherens junctions contributing a central role in barrier regulation.

2.2.1. Tight Junction (TJ)

In BBB and BRB, the very tight control of solute and fluid flux across the endothelium is conferred by well-developed tight junctions. Evidence of tight junction complexity in these tissues was demonstrated in studies of freeze fracture sections and electron microscopy, correlated to the density of branch points on tight junction strands (Liebner, Kniesel et al. 2000). In ultrathin sections of epithelial cells, tight junctions appear as contact points of close apposition, or “kissing points”, where the two lipid bilayers are indistinguishable; these are located specifically at the most apical side of the polarized lateral membrane (Farquhar and Palade 1963). In contrast, in endothelial barriers, these same contact points are localized at several points along the paracellular space between cells as well as contacts within a cell forming the capillary lumen (Reese and Karnovsky 1967). The molecular mechanisms that regulate the difference in polarization between epithelial and endothelial cells, have not been determined.

Tight junctions serve two main functions: gate function, that restricts the passage of molecules through the paracellular space, and fence function, that confers cell polarity by preventing movement of lipids and proteins between the apical and basolateral plasma membrane (van Meer and Simons 1986, Mandel, Bacallao et al. 1993). However, additional roles of tight junctions in several cell-signaling processes such as cell proliferation, gene expression, and differentiation, have been described (Takano, Kojima et al. 2014, Osanai, Takasawa et al. 2017).

At a molecular level, the tight junctions consist of over 40 proteins which can be categorized into:1) transmembrane proteins, including the tetraspanin families of claudin and MARVEL (MAL and related proteins for vesicle trafficking and membrane link) proteins, and the single span proteins from the junctional adhesion molecules (JAM) family; and 2) cytoplasmic-scaffold proteins: including members of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase homologue (MAGUK) family like zonula occludens (ZO), and other membrane associated proteins such as afadin (AF6), and cingulin (Bazzoni and Dejana 2004, Balda and Matter 2016) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Paracellular Transport.

In the BRB, molecules can move from the blood (luminal) into the retinal (abluminal) side via the paracellular space, which is located in between two adjacent cells (blue line). Some of the molecules central to control of paracellular transport of the BRB are indicated.

2.2.1.1. Claudins

The claudin family are tetraspan transmembrane proteins that contribute a crucial role in paracellular transport by forming ion selective barriers and pores. Claudins possess cytoplasmic, intracellular NH2- and COOH- termini and two extracellular loops. Mutational analyses have reveal that amino acid charges at the first extracellular loop of claudins, defines the ion selectivity property of these proteins, while the second extracellular loop is involved in claudin-claudin interactions (Angelow and Yu 2009, Krause, Winkler et al. 2009, Veshnyakova, Krug et al. 2012, Rossa, Ploeger et al. 2014). In addition, the carboxy-terminus of claudins interacts with the first of three PDZ domains on ZO-1 (Itoh, Furuse et al. 1999). This allows the connection between transmembrane proteins and the actin cytoskeleton, and controls the localization of claudins at cell contacts.

There are 27 known mammalian claudin members (Mineta, Yamamoto et al. 2011). Claudins located in the same plasma membrane can polymerize by cis-interactions into homomeric or heteromeric strands, and from adjacent cells (trans-interaction), claudins interact with other claudins in a homotypic (same type of claudin) or heterotypic (different claudin) fashion. Expression of various claudin isoforms yields tissue specific barrier properties. Indeed, claudins are subdivided into sealing claudins and pore forming claudins that are ion specific paracellular channels (Gunzel and Yu 2013). Moreover, overexpression of claudin in non-tight junction forming cells like fibroblast, leads to formation of a tight junction-like networks (Furuse, Sasaki et al. 1998), supporting the important role of claudins in tight junction formation between adjacent cells.

Measurements of mRNA in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells revealed that claudins -1, -3, -5, -8, -10, -12, -15, -17, -19, -20, -22 and -23 are expressed in BBB. From these, claudin-5 is the most abundant in more than 500-fold greater than the other claudin subtypes (Ohtsuki, Yamaguchi et al. 2008, Daneman, Zhou et al. 2010, Luo, Xiao et al. 2011), while claudins -1, -3 and -12 have a lower but inducible expression (Liebner, Corada et al. 2008, Sadowska, Ahmedli et al. 2015).

In contrast, mouse retinas from the postnatal day 18 (P18) show mRNA expression of claudin -1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -7, -9, -10, -11, -12, -13, -14, -17, -19, -20, -22 and -23. Like in the brain, claudin-5 is the most abundant of the isoforms, and it localizes at the tight junctions of retinal vessels, together with claudin -1 and -2. Claudins -1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -12, -22 and -23 are regulated in retinal development. All demonstrate increases in expression, especially at P15, coincident with the formation of the iBRB in retinal capillaries. After this, their expression decreases, with the exception of claudin-22. Moreover, after oxygen-induced retinopathy, claudin-2 and -5 are overexpressed from P15 to P21 (Luo, Xiao et al. 2011), suggesting that claudins regulate the barrier function of retinal endothelial cells. In accordance with the high levels of claudin-5 in both BBB and BRB, claudin-5-deficient mice die within 10 hours after birth due to BBB disruption. These mice show no abnormal development or morphology of blood vessels and no abnormal bleeding or edema, but a leaky BBB towards small molecules <800 Da (Nitta, Hata et al. 2003). No BRB defects have been reported in claudin-5 KO mice. However, ongoing studies focusing on the BRB and the BBB in pathologies that model diabetes, ischemia, and strokes have identified loss of claudin-5 and an increase in permeability (Argaw, Gurfein et al. 2009, Muthusamy, Lin et al. 2014), thus supporting the important role of claudin-5 in BRB. Claudin-1 deficient mice die within the first day of birth caused by skin barrier disruption, however, no BBB or BRB alteration has been reported (Furuse, Fujita et al. 1998, Furuse, Hata et al. 2002); thus indicating that claudin-1 expression is not crucial for endothelial barrier formation or maintenance. Nevertheless, some studies suggest that claudin-1 is expressed in retinal vasculature of adult mice, and its content decreases in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Yu, Gong et al. 2015), and in a model of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis (EAU) (Xu, Dawson et al. 2005).

Not all retinal claudins are restricted to blood vessels. In contrast to BBB studies, in the BRB, there are no reports related to claudin-3 changes in retinal vasculature associated with altered permeability. In fact, claudin-3 in the retina, is expressed in the retinal ganglion cell layer (RGC). Likewise, other claudin isoforms were found in non-endothelial retinal tissues. Claudin-4 and -23 are localized at the RGC layer, claudin-4 and -12 are expressed in the outer plexiform layer (OPL), and claudin-23 was also found in the inner nuclear layer (INL) (Luo, Xiao et al. 2011). The roles of these claudins in the retinal tissue have not been studied yet.

Together, these data suggest that claudins, particularly claudin-5, are important in the regulation of the CNS barriers. However, additional claudin isoforms that have the potential to regulate BRB properties, require further investigation.

2.2.1.2. MARVEL proteins

MARVEL (MAL and related proteins for vesicle trafficking and membrane link) proteins contain a conserved four-transmembrane MARVEL domain. The MARVEL proteins are characterized by their involvement in vesicle trafficking (Sanchez-Pulido, Martin-Belmonte et al. 2002). The tight junction-associated MARVEL protein (TAMP) family consist of occludin (MARVELD1), tricellulin (MARVELD2), and MARVELD3 (Raleigh, Marchiando et al. 2010).

2.2.1.2.1. Occludin

Occludin (MARVELD1), a ~60kD membrane protein, was the first identified in tight junctions from chick liver junctional fractions. Hydrophilicity plot and cDNA sequence analyses showed that occludin is a tetraspan transmembrane protein that has two extracellular loops and cytoplasmic NH2 and COOH termini (Furuse, Hirase et al. 1993, Feldman, Mullin et al. 2005). The N-terminus of occludin interacts with Itch, E3-ubiquitin-protein ligase that regulates occludin degradation (Traweger, Fang et al. 2002) and endocytosis (Murakami, Felinski et al. 2009). The distal C-terminus of occludin forms a coiled-coil region that binds to the scaffold proteins ZO-1 (Furuse, Itoh et al. 1994), ZO-2 (Jesaitis and Goodenough 1994), and ZO-3 (Haskins, Gu et al. 1998), specifically, to the guanylate kinase like (GUK) domain of ZO-1 (Tash, Bewley et al. 2012).

Occludin expression correlates with barrier properties. Overexpression of occludin in Madin Darby Canine kidney cells (MDCK) causes an increase in trans-epithelial resistance, while suppression of occludin increases solute flux, and truncation of the carboxyl tail causes an increase in permeability and tight junction disorganization (Balda, Whitney et al. 1996, Kevil, Okayama et al. 1998, Yu, McCarthy et al. 2005). Likewise, in BBB and BRB, high levels of occludin expression have been observed associated with increased barrier properties of vascular beds (Hirase, Staddon et al. 1997).

The role of occludin in barrier properties is complex, and current research suggests this protein contributes to regulation of barrier properties, rather than acting directly as a structural protein in TJs. Occludin mutations have recently been identified in a number of families leading to microcephaly (small head size), brain calcification, polymicrogyria (excessive folding of the brain cortex), lack of motor development, reduced vision, and, in some families, renal involvement (O'Driscoll, Daly et al. 2010, LeBlanc, Penney et al. 2013, Elsaid, Kamel et al. 2014). Occludin knockout mice revealed that occludin is not required for tight junction formation or basal intestinal epithelia barrier properties (Saitou, Fujimoto et al. 1998, Saitou, Furuse et al. 2000). These animals did, however, express several abnormalities such as brain calcification, male sterility, inability for female mice to nurse, and gastric epithelial hyperplasia (Saitou, Furuse et al. 2000, Schulzke, Gitter et al. 2005).

More recent studies show that occludin has a more complex function that includes the regulation of cell signaling, tight junction protein trafficking and cell growth. In these studies, specific occludin phosphosite changes and their role in barrier regulation and cell signaling have been identified (Sundstrom, Tash et al. 2009, Cummins 2012). For example, PKCη –induced phosphorylation of occludin at T403 and T404 residues enhances TJ assembly and maintenance in epithelial cells (Suzuki, Elias et al. 2009). In contrast, phosphorylation of occludin at Y398 and Y402 by c-Src (Elias, Suzuki et al. 2009), or at S408 by CK2 kinase, causes its dissociation from ZO-1 leading to tight junction destabilization. In the case of S408, this is due to an increased occludin-occludin interaction that results in small cation paracellular flux via claudins -1 and 2-based pores (Raleigh, Boe et al. 2011). Moreover, studies in bovine retinal endothelial cells (BREC) and in ischemia reperfusion model, showed that the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) by VEGF, induces occludin phosphorylation on S490 in a mechanism dependent of PKCβ. As a consequence, occludin is ubiquitinated and endocytosed promoting retinal endothelial permeability (Murakami, Felinski et al. 2009, Murakami, Frey et al. 2012, Muthusamy, Lin et al. 2014). Collectively, these studies reveal that post-translational modifications of occludin including multiple phosphorylation sites and ubiquitination, regulate barrier properties in retinal endothelial cells, through TJ protein endocytosis. The TJ protein occludin, while not required for junction assembly, appears to act as a regulator of barrier properties.

In addition, recent work reveals a role of occludin in cell growth regulation. The use of phospho-specific antibodies surprisingly revealed occludin localization in centrosomes with specific Ser490 phosphorylation increase during mitosis (Runkle, Sundstrom et al. 2011, Liu, Dreffs et al. 2016). Mutation of Ser490 to alanine retarded MDCK cell growth and completely prevented VEGF-induced proliferation and tube formation in cell culture and neovascularization in vivo (Liu, Dreffs et al. 2016). A second phosphorylation site, also located in the coiled-coil domain also contributes to proliferation and tight junction formation. It has been found that MDCK epithelial cells undergo post-contact proliferation necessary for proper epithelial maturation and tight junction formation. Inhibition of occludin Ser471 phosphorylation by either an alanine mutation or inhibition of the G-protein regulated kinase that targets this site, prevents this epithelial maturation and blocks tight junction formation with no effect on adherens junction formation (Bolinger, Ramshekar et al. 2016). Together these data show the complex role of occludin in barrier regulation, cell growth, angiogenesis, and permeability transport regulation. Further, the studies point to an intimate relationship in growth and differentiation of cells that form tight junctions and a specific role for occludin in regulating these processes.

2.2.1.2.2. MARVELD2 and D3

Tricellulin (MARVELD2) is a ~64kDa transmembrane protein localized at regions where 3 epithelial or endothelial cells make contact (Ikenouchi, Furuse et al. 2005, Iwamoto, Higashi et al. 2014). Like occludin, tricellulin has a long C-terminus tail but they only share about a 32% homology. Interestingly, tricellulin-deficient mice, as well as occludin-deficient mice, develop hearing loss (Riazuddin, Ahmed et al. 2006, Kitajiri, Katsuno et al. 2014, Kamitani, Sakaguchi et al. 2015).

A closer look at tricellulin organization in both cells and animals show that loss of occludin alters tricellulin localization. In the absence or downregulation of occludin, tricellulin was observed to localized at the bicellular tight junctions rather than at the tricellular tight junctions (Ikenouchi, Sasaki et al. 2008, Kitajiri, Katsuno et al. 2014). These results might suggest that in the absence of occludin, tricellulin can compensate for the formation of bicellular tight junctions.

Majority of the studies on tricellulin have been on epithelial cells, and more recent work revealed that tricellulin is only present in endothelial cells of the BBB and BRB but not in vascular beds of other tissues (Iwamoto, Higashi et al. 2014). This observation gives rise to unanswered question about the role of tricellulin at regulating paracellular barrier and paracellular transport at the BBB and BRB.

MARVELD3 is the third member of the MARVEL family and is also a tetraspan protein but lacks the carboxyl tail found in occludin and tricellulin (Steed, Rodrigues et al. 2009). The role of MARVEL D3 in the BBB and BRB remains unclear.

2.2.1.3. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAM)

JAMs are single-span proteins that belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily because they contain at least one IgG domain at its extracellular N-terminus (Martin-Padura, Lostaglio et al. 1998, Williams, Martin-Padura et al. 1999). The cytoplasmic tails of JAMs contain a PDZ binding sequence that interacts with PDZ domain of ZO-1. Like the 2nd extracellular loop of claudins, the extracellular domain of JAMs can associate to JAMs from adjacent cells (trans-interaction) or in the same cell (cis-interactions) in a homophilic (same type of JAM) or heterophilic (different type of JAM) manner (Bazzoni, Martinez-Estrada et al. 2000, Arrate, Rodriguez et al. 2001). But in contrast with claudins, JAMs do not form tight junction strands, instead they facilitate junctional assembly. JAMs are the first TJ proteins to appear during epithelial junction assembly.

JAM-A co-localizes with AF-6 and the Par3 at the intercellular junctions of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and its expression in fibroblasts promotes ZO-1, AF6, and occludin localization at cell-cell contacts, leading o barrier formation (Bazzoni, Martinez-Estrada et al. 2000, Luo, Fukuhara et al. 2006).

In the cerebral and retinal endothelium, JAM-A is the predominant JAM isoform (Aurrand-Lions, Johnson-Leger et al. 2001, Tomi and Hosoya 2004). The exact role JAMs play in the regulation of paracellular barrier and transport of the BBB and BRB remain unclear; however, recent studies suggest a role of JAM in diapedesis. JAM-A expression on monocytes facilitates its movement across the BBB (Williams, Anastos et al. 2015), while JAM-A knockout and endothelial specific JAM-A deficient mice, prevent neutrophil transmigration (Woodfin, Reichel et al. 2007). Further, although JAM-C and JAM-B are expressed at the junctions of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), JAM-C deficient animals showed increased JAM-A expression and enhanced retinal vascularization (Daniele, Adams et al. 2007, Economopoulou, Avramovic et al. 2015) suggesting a role for JAMs in retinal angiogenesis.

Together these data indicate that JAMs contribute to several mechanisms including cell migration, immune cell infiltration and angiogenesis in the BBB and BRB. However, further studies are clearly needed in order to determine the exact role of the different JAMs in the BBB and BRB formation and maintenance.

2.2.1.4. Zonula occludens (ZO)

Zonula occludens (ZO) are large, >200kDa scaffold proteins that connect transmembrane proteins with the cytoskeleton and play an important role in tight junction organization. ZOs form part of the MAGUK family and there are 3 isoforms described: ZO-1, -2, and -3 (Stevenson, Siliciano et al. 1986, Gumbiner, Lowenkopf et al. 1991, Haskins, Gu et al. 1998).

ZO proteins contain three PDZ domains that allow interaction both with proteins that have a PDZ domain or proteins with a PDZ binding motif domain like claudins and JAMs (Furuse, Itoh et al. 1994, Itoh, Furuse et al. 1999, Ebnet, Schulz et al. 2000). Further, occludin interacts with a Src homology 3, guanylate kinase GUK homology domain (Tash, Bewley et al. 2012). ZO proteins serve as links between the junctional complexes and the cytoskeleton by their ability to bind actin, α-catenin, and afadin (AF6) (Itoh, Nagafuchi et al. 1997, Yamamoto, Harada et al. 1997, Wittchen, Haskins et al. 1999), thus promoting TJ protein assembly at cell-cell contacts.

ZO play a critical role in tight junction formation. In the absence of all ZO isoforms, impaired formation of tight junctions is observed, claudins fail to polymerize while no effects on the adherens junction is observed (Umeda, Ikenouchi et al. 2006, Ooshio, Kobayashi et al. 2010). Additionally, ZO-1 deficient mice are embryonic lethal and express defects in the vasculature and neural tube development (Katsuno, Umeda et al. 2008). Several studies focusing on pathologies disrupting the BBB and the BRB have revealed that loss/reduction of ZO-1 has a correlation with an increase in paracellular permeability (Yeh, Lu et al. 2007, Muthusamy, Lin et al. 2014), thus supporting ZO-1 as a marker of leakiness in endothelial barriers. ZO-2 and ZO-3 are also expressed in BBB and BRB however, their specific role in endothelial barriers have not been addressed yet.

2.2.2. Adherens Junctions (AJ)

AJs play a critical role in cell-cell adhesion, cell polarity, contact inhibition, and paracellular transport regulation. The adherens junctions of the iBRB includes (VE)-cadherin of the cadherin superfamily. VE-cadherin is a transmembrane Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion protein with a conserved cytoplasmic tail that binds to β-catenin. In vivo studies of transgenic mice deficient of VE-cadherin, which is embryonic lethal by E9.5, have demonstrated that VE-cadherin is required for proper lumen formation and maintenance of newly formed vessels (Carmeliet, Lampugnani et al. 1999). VE-Cadherin has an intimate relation to the VEGFR and is a major control point for regulation of barrier development, paracellular permeability and growth control but a detailed discussion is beyond this review. (For more information on adherens junctions in paracellular barrier refer to reviews (Bazzoni and Dejana 2004, Giannotta, Trani et al. 2013, Stamatovic, Johnson et al. 2016)).

3. DEVELOPMENT OF THE INNER BLOOD-RETINAL BARRIER

3.1. The Neurovascular Unit (NVU)

Development of this specific barrier in the brain and retina is the result of close association of neurons, glia and pericytes with the vascular endothelium. This cell complex is termed the Neuro-Vascular Unit (NVU) reflecting the interdependence of the vasculature barrier properties and blood flow regulation on the associated glia, pericytes and neurons and the reciprocal dependence on vascular support. Together, the NVU provide a selectively regulated environment for proper neuronal function made possible through expression of specific factors that promote the formation of the tight junction at cell contacts, with decreased transcytosis within endothelial cells. Recent research has provided novel insight into the development of the BBB and BRB in the NVU and these novel findings are discussed below.

3.2. Development of the blood-retinal barrier

The formation of the BRB requires the vascularization of the retina and differentiation of the retinal endothelium to the specialized iBRB. The processes of growth and BRB formation or barriergenesis are intimately regulated and both will be briefly described.

3.2.1. Development of retinal vasculature

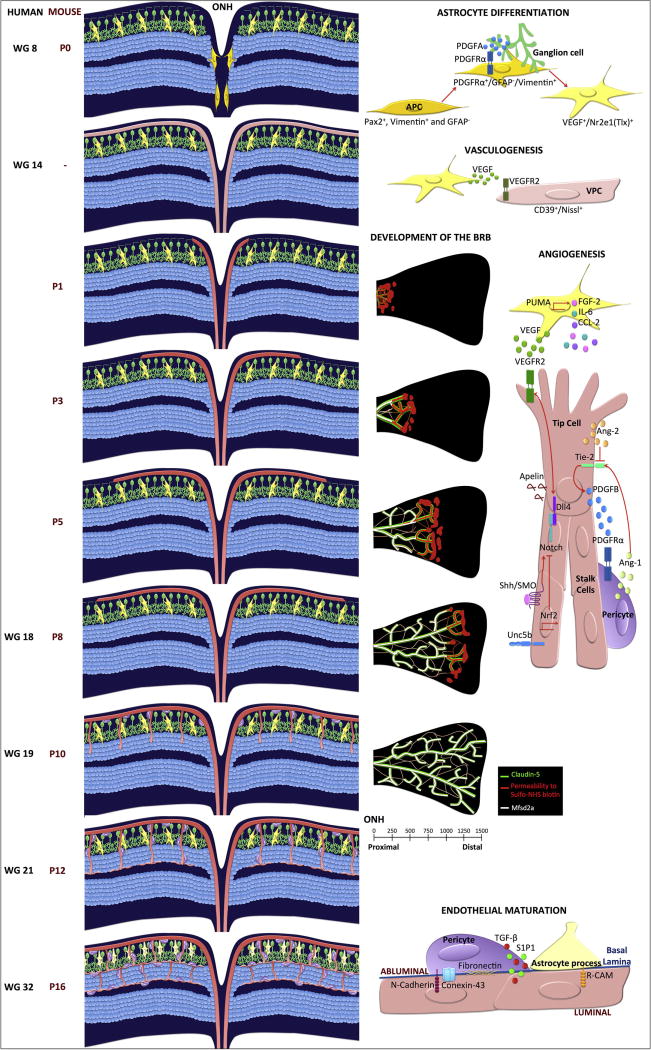

In early human retinal development, a hyaloid network of vasculature emerges from the central hyaloid artery in the optic nerve, providing vascular support for the whole eye. In humans, hyaloid vessels regress around the week of gestation (WG) 14 and retinal vasculature starts to develop and continues until the day of birth. This process is conducted by two different mechanisms: vasculogenesis, that refers to the maturation of progenitor cells to the primary vascular bed; and angiogenesis, that consist in the sprouting of vessels from the already existing vasculature.

In humans the retinal vasculogenesis is considered to occur from WG 14 to WG 18 with the accumulation of a population of pre-differentiated cells called vascular patent cells (VPC). VPCs cover 2/3 of the superficial plexus in the retina and express ADPase/CD39 and CXCR (CD39+ and Nissl+) as markers. Since the exact origin of precursor cells is still unknown, and in mice, a vasculogenic process has not been reported yet, the existence of VPCs has been questioned.

Vasculogenesis then is followed by angiogenesis at WG 18. The primary sprouts come from the optic nerve head and expand radially along the vitreal surface in the retina, attracted by VEGF secreted from astrocytes. In the primary plexus, the differentiation of major arteries and veins take place, followed by sprouting into the deep retinal tissue. At WG 21, the first capillary bed at the outer layer is apparent and the sprouting continues to the inner plexus in a process that coincides with the eye opening. This process culminates in humans by the WG 32, when hyaloid vasculature regression also has been completed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Development of retinal vasculature and the inner blood-retinal barrier.

Left panel, retinal cross sections demonstrating vascular development and indicated times, middle panel shows the development of the iBRB, and the right panel depicts the molecular mechanisms regulating angiogenesis or barriergenesis. During retinal vascular development, astrocyte precursor cells (APC in gold) emerge from the optic nerve head and migrate towards the PDGF secreted by ganglion cells (green). The astrocytes (yellow) differentiation program starts once the APCs leave the ONH and emerge into the retinal tissue. Inside the retina, the hypoxic environment induces astrocytes to secrete VEGF. In humans at WG14, the vascular patent cells (VPC; light pink) migrate into the retina expanding though the perifoveal region. VPCs differentiate to form the first vascular plexus layer. In rodents, this process has not been observed, instead vascular sprouting across the retinal ganglion layer is observed (P8). Astrocytes release additional chemotactic factors that promote endothelial cell sprouting into the deep layers of the retina (P10-P12). Finally, pericyte recruitment and glial processes interact with the vascular endothelium to create the neurovascular unit (WG32, P16). The development of the iBRB occurs at the same time from P1 to P10. The new sprouts show leakiness (red color in middle pannel) while the stalk cells located closer to the ONH have already developed a functional BRB. This barriergenesis correlates with Msfsd2a expression (white). All endothelial cells express claudin-5 (green).

Much of our understanding of retinal vascular development comes from mice, which undergoes hyaloid regression and retinal vascular development that begins after birth. In mice, retinal angiogenesis starts at the day of birth with the formation of the superficial plexus that covers the retinal surface by P8. This is followed by vascular sprouting into the deep and intermediate plexus layers, formed at P7-P12 and P14-21, respectively.

Retinal angiogenesis is mainly governed by the expression of the VEGFR2, which regulates endothelial migration and proliferation in response to VEGFA secreted by glia and neurons (Hughes, Yang et al. 2000, Penn, Madan et al. 2008). During the angiogenic process, two endothelial cell types can be distinguished: endothelial tip cells, which establish the direction of the sprouting by the presence of filipodia that extend toward VEGF source; and stalk cells, an intermediate population of cells in the vascular plexus that proliferate extending the length of the vessels (Figure 4B). Tip cell express delta like 4 (Dll4), PDGFB and apelin ligands (Gerhardt, Golding et al. 2003, del Toro, Prahst et al. 2010, Siemerink, Klaassen et al. 2013), while the netrin receptor Unc5b and VEGFR are upregulated in stalk cells (Larrivee, Freitas et al. 2007, Patel-Hett and D'Amore 2011).

Cell fate in vascular endothelial cells is controlled by Notch signaling (Kume 2009, Tung, Tattersall et al. 2012, Blanco and Gerhardt 2013). There are 5 isoforms of Notch that can be activated by Jagged-1 and -2, or by delta like (Dll)-1 and -4 ligands. Upon activation, Notch is cleaved by tumor necrosis factor beta converting enzyme and the gamma secretase complex to release the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). NCID acts as a transcription factor and co-activator of Mastermind-like (MAML). In retinal endothelial cells, the transcription factor NF-E2- related factor 2 (Nrf2) promotes angiogenic sprouting by suppressing Dll4/Notch signaling (Wei, Gong et al. 2013), as a consequence, tip cell markers, including VEGFR2 are overexpressed (Hellstrom, Phng et al. 2007, Lobov, Renard et al. 2007, Suchting, Freitas et al. 2007), thus supporting the role of Notch signaling in cell fate determination. Finally, the vasculature is remodeled in a leukocyte dependent manner by the induction of endothelial apoptosis in a Fas ligand (or CD18)-dependent process (Ishida, Yamashiro et al. 2003) endosialin (Simonavicius, Ashenden et al. 2012).

3.2.2. Development of functional blood-retinal barrier

Little is known about the specialization of a iBRB. Studies of claudin-5 expression during retinal vascular development suggest that tight junctions are present once the endothelial cells make contacts between them. However, molecular mechanisms and the specific time for iBRB development were not studied before. Recent work reveals that the permeability of 3–10 kDa dextran, Sulfo-NHS-biotin and HRP molecules is restricted to the new endothelial sprouts and that gradually, this permeability decreases in the stalk cells, forming a functional BRB (Chow and Gu 2017). Interestingly, the leakiness of these molecules completely ceased at P10, suggesting that after P10, the new vascular sprouts form a functional BRB at the same time (Figure 4).

According with previous results, claudin-5 was expressed in both stalk and tip cells but surprisingly, electron microscopy images showed that sprouting cells have functional tight junctions but increased transcytosis. When they analyzed the role of Mfsd2a, they found that its expression was limited to endothelial cells with functional BRB and that deletion of Mfsd2a gene resulted in leakiness and incomplete formation of BRB, suggesting that Mfsd2a suppress transcytosis and promotes BRB formation. On the other hand, caveolin-1-deficient mice demonstrated early BRB formation associated with decreased transcytosis.

Since animal models of pericyte loss show BBB and BRB leakiness, aberrant TJs, elevated transcytosis, and downregulation of Mfsd2a, specifically at the endothelial cells uncovered by pericytes (Armulik, Genove et al. 2010, Bell, Winkler et al. 2010, Ben-Zvi, Lacoste et al. 2014), Dr. Gu group proposed that pericytes may suppress transcytosis and promote a functional BRB formation in a mechanism dependent on Mfsd2 (Chow and Gu 2017). Further studies of pericyte loss in Mfsd2a- and caveolin-1-deficient mice are needed to test this hypothesis.

Together, these studies suggest that the BRB development is regulated by reduction of transcytosis in a mechanism dependent of Mfsd2 expression, and that this occurs in parallel to angiogenesis. It should be noted that formation of the tight junction complex is simultaneously needed to prevent paracellular flux and additional studies on formation and organization of the junctional complex in development are needed.

4. NEW INSIGHTS IN BRB DEVELOPMENT

Recent studies have been focused in the discovery of new molecules that control retinal angiogenesis and barriergenesis.

4.1. Pericyte Endothelial Interactions and Angiopoietins

During retinal vascular development, endothelial tip cells express high levels of PDGF-B, thus inducing pericyte recruitment at the new vessels (Gerhardt and Betsholtz 2003). Immediately following, tight junction formation takes place between endothelial cells (Kim, Kim et al. 2009). The pericytes enwrapped endothelial cells and establish cell-cell contacts through the junction proteins N-Cadherin (Gerhardt, Wolburg et al. 2000), Conexin-43 (Bobbie, Roy et al. 2010), and fibronectin adhesion plaques (Diaz-Flores, Gutierrez et al. 2009). This interaction is important to promote endothelial maturation and BRB maintenance. In addition, pericytes secrete factors that regulate endothelial functions (Antonelli-Orlidge, Smith et al. 1989) or promote glial interactions (Armulik, Genove et al. 2010). The pericyte coverage on vessels correlates with endothelial barrier properties and in the retina, the ratio of pericytes/endothelial cells is 1:1 (Stewart and Tuor 1994). The requirement for pericytes is demonstrated by in vivo models of induced pericyte loss that lead to retinal vasculature damage with increased permeability (Daneman, Zhou et al. 2010).

Pericyte secreted factors affect endothelial growth and differentiation. Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) is secreted by pericytes and binds to its receptor Tie-2 on retinal endothelial cells promoting remodeling, maturation and differentiation (Sato 1995, Uemura, Ogawa et al. 2002, Bergers and Song 2005). On the other hand, angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), also binding the Tie2 receptor, activates autocrine signals in endothelial cells that together with VEGF promote angiogenesis. Interestingly, Ang-2 alone promotes vascular regression (Asahara, Chen et al. 1998). Altered ratio of Ang-1 and Ang-2 may contribute to retinal eye disease such as diabetic retinopathy with increased Ang-2 expression (Patel, Hykin et al. 2005). The over-expression of Ang-2 in vivo, causes pericyte migration and vascular leakage, due to the deficiency in PDGF-B production (Pfister, Wang et al. 2010). Likewise, PDGF-B deficient mice show similar abnormalities as patients with diabetic retinopathy, including changes in vessel diameter, micro aneurysms, and vessel regression (Enge, Bjarnegard et al. 2002). Ang-2 promotes loss of endothelial barrier function, by the induction of VE-Cadherin phosphorylation and degradation (Rangasamy, Srinivasan et al. 2011), while Ang-1 prevent the degradation of junction complex (Gavard 2009, Lee, Kim et al. 2009, Siddiqui, Mayanil et al. 2015). In summary, Ang-1 and -2 have opposing effects in BRB properties with Ang-1 promoting patent iBRB.

Other factors released by pericytes also affect endothelial-pericyte interaction. TGF-β, maintains BRB properties by the inhibiting proliferation and migration of retinal endothelial cells (Murphy-Ullrich and Poczatek 2000, Garcia, Darland et al. 2004). In addition, Sphingosine1-phosphate-1 (S1P1) is up-regulated in pericytes but its exact role in vessel maturation is still unknown (Jain and Booth 2003).

4.2. Sonic hedgehog (Shh)

Shh has a crucial role in vascular development and angiogenesis (Pola, Ling et al. 2001, Pola, Ling et al. 2003, Surace, Balaggan et al. 2006). In normal conditions Shh receptor Smoothened (SMO) constitutively inhibits Patched (Ptch) receptor. Upon Shh binds to SMO, Ptch is released and activates cell signaling that includes the activation of Gli transcription factors. A recent study reveals that Shh is secreted in brain astrocytes during development and in adult tissue and conditional gene deletion of SMO leads to loss of BBB properties (Alvarez, Dodelet-Devillers et al. 2011). This study also revealed Shh may promote endothelial barrier function, by the control of pro-inflammatory cytokine release, as well as leukocyte adhesion and migration. Recent studies suggest that cell autonomous Shh signaling may also contribute BRB function (manuscript under review in ExpEyeRes).

4.3. Wnt family

Wnt signaling molecules are required for blood-brain and BRB formation. Wnts are cysteine-rich glycoproteins that bind with high affinity to frizzled (FZD) receptors. At least, 19 Wnts and 10 FZD receptors are expressed in mammals. Despite the diversity of these molecules with complex signaling pathways, most of the Wnt-FZD interactions can activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Wnt3, Wnt7a and Wnt7b promote angiogenesis and BBB formation though the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in endothelial cells (Liebner, Corada et al. 2008, Stenman, Rajagopal et al. 2008, Daneman, Agalliu et al. 2009). Wnt7a and Wnt7b-deficient mice have reduced angiogenesis, abnormal vascular structures and defects in BBB formation. Interestingly, knocking down Gpr124, an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is expressed in endothelial cells during development, resulted in the same vascular defects as Wnt7. When the signal interaction between these molecules was analyzed, it was found that Gpr124 acts as a co-activator of Wnt7a and 7b leading to β-catenin-dependent signaling (Kuhnert, Mancuso et al. 2010, Anderson, Pan et al. 2011, Cullen, Elzarrad et al. 2011, Zhou and Nathans 2014, Posokhova, Shukla et al. 2015). More recent studies show that in coordination with this atypical signaling complex, the glycosylphospatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor Reck also controls vascular invasion through the modulation of endothelial tip cell functions (Vanhollebeke, Stone et al. 2015). Together, these results demonstrate the role of a complex formed by Wnt7a/Wnt7b/Gpr124/Reck that activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling thus promoting retinal angiogenesis.

4.4. Norrin signaling

Although it is not related to Wnt molecules, Norrin can bind with high affinity to the FZD4 receptor (Smallwood, Williams et al. 2007) and recent studies reveal this signaling is required for iBRB barriergenesis. Norrin is a member of the TGF-β superfamily that is produced by Müller glia cells during retinal development (Ye, Wang et al. 2009). Norrin induces the dimerization of FZD4 with the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6), in a mechanism dependent of the chaperon tetraspanin (TSPAN12) (Junge, Yang et al. 2009). As a result, phosphorylation of β-catenin signaling is activated (Xu, Wang et al. 2004, Ye, Wang et al. 2009, Wang, Rattner et al. 2012).

In humans, loss of function mutations in FZD4, LRP5, TSPAN12 and the Norrin gene NDP, result in severely defective retinal hypo vascularization syndromes and blindness (Robitaille, MacDonald et al. 2002, Jiao, Ventruto et al. 2004, Toomes, Bottomley et al. 2004, Nikopoulos, Venselaar et al. 2010, Poulter, Ali et al. 2010, Ye, Wang et al. 2010). These phenotypes can be recapitulated in mice models within the same mutations or with the knock out mice for Norrin, FZD4, LRP5 or TSPAN12. All of these models lack the deep capillary beds that flank the inner nuclear layer of the retina, and demonstrate tortuosity and hemorrhage (Rehm, Zhang et al. 2002, Junge, Yang et al. 2009, Paes, Wang et al. 2011, Chen, Stahl et al. 2012). Gene deletion studies in animals reveals a requirement for Norrin signaling through the FZD4 receptor complex to β-catenin for barriergenesis. Gene deletion of any of these components leads to reduced claudin 5 expression and increased PLVAP expression and increased retinal vascular permeability. Similar results were observed in regions of the brain such as cerebellum but not the cortex. Importantly, expression of stabilized β-catenin is sufficient to largely restore vascular defects in Norrin and FZD4 KO mice (Zhou, Wang et al. 2014). Collectively, these results demonstrate Norrin is specifically required for BRB angiogenesis and barriergenesis controlling both deep capillary formation and differentiation to the iBRB. Further, these studies reveal that angiogenesis and barriergenesis in the retina are developmentally linked processes.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Changes in retinal vascular permeability contribute to loss of vision and the pathophysiology of a number of blinding eye diseases including diabetic retinopathy with evidence for growth factor and cytokine induced alterations to both the junctional complex and paracellular route and the vesicle trafficking and the transcellular route. Recent research has provided novel insight into the mechanisms of formation of the unique vascular barrier of the iBRB and BBB. Understanding the factors that promote barriergenesis may lead to novel therapeutic options to restore the iBRB and preservation of vision in diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH EY012021 (DAA), Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc (University of Michigan), and the American Diabetes Association Minority Postdoctoral Fellowship Award #4-16-PMF-003 (MDC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez JI, Dodelet-Devillers A, Kebir H, Ifergan I, Fabre PJ, Terouz S, Sabbagh M, Wosik K, Bourbonniere L, Bernard M, van Horssen J, de Vries HE, Charron F, Prat A. The Hedgehog pathway promotes blood-brain barrier integrity and CNS immune quiescence. Science. 2011;334(6063):1727–1731. doi: 10.1126/science.1206936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KD, Pan L, Yang XM, Hughes VC, Walls JR, Dominguez MG, Simmons MV, Burfeind P, Xue Y, Wei Y, Macdonald LE, Thurston G, Daly C, Lin HC, Economides AN, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Yancopoulos GD, Gale NW. Angiogenic sprouting into neural tissue requires Gpr124, an orphan G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):2807–2812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019761108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RG. Caveolae: where incoming and outgoing messengers meet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(23):10909–10913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreone BJ, Chow BW, Tata A, Lacoste B, Ben-Zvi A, Bullock K, Deik AA, Ginty DD, Clish CB, Gu C. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Is Regulated by Lipid Transport-Dependent Suppression of Caveolae-Mediated Transcytosis. Neuron. 2017;94(3):581–594. e585. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelow S, Yu AS. Structure-function studies of claudin extracellular domains by cysteine-scanning mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(42):29205–29217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli-Orlidge A, Smith SR, D'Amore PA. Influence of pericytes on capillary endothelial cell growth. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140(4):1129–1131. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argaw AT, Gurfein BT, Zhang Y, Zameer A, John GR. VEGF-mediated disruption of endothelial CLN-5 promotes blood-brain barrier breakdown. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(6):1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808698106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2010;468(7323):557–561. doi: 10.1038/nature09522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrate MP, Rodriguez JM, Tran TM, Brock TA, Cunningham SA. Cloning of human junctional adhesion molecule 3 (JAM3) and its identification as the JAM2 counter-receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(49):45826–45832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Chen D, Takahashi T, Fujikawa K, Kearney M, Magner M, Yancopoulos GD, Isner JM. Tie2 receptor ligands, angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2, modulate VEGF-induced postnatal neovascularization. Circ Res. 1998;83(3):233–240. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrand-Lions M, Johnson-Leger C, Wong C, Du Pasquier L, Imhof BA. Heterogeneity of endothelial junctions is reflected by differential expression and specific subcellular localization of the three JAM family members. Blood. 2001;98(13):3699–3707. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Matter K. Tight junctions as regulators of tissue remodelling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;42:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Whitney JA, Flores C, Gonzalez S, Cereijido M, Matter K. Functional dissociation of paracellular permeability and transepithelial electrical resistance and disruption of the apical-basolateral intramembrane diffusion barrier by expression of a mutant tight junction membrane protein. J Cell Biol. 1996;134(4):1031–1049. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni G, Dejana E. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(3):869–901. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni G, Martinez-Estrada OM, Orsenigo F, Cordenonsi M, Citi S, Dejana E. Interaction of junctional adhesion molecule with the tight junction components ZO-1, cingulin, and occludin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(27):20520–20526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M905251199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron. 2010;68(3):409–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi A, Lacoste B, Kur E, Andreone BJ, Mayshar Y, Yan H, Gu C. Mfsd2a is critical for the formation and function of the blood-brain barrier. Nature. 2014;509(7501):507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature13324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Song S. The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance. Neuro Oncol. 2005;7(4):452–464. doi: 10.1215/S1152851705000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco R, Gerhardt H. VEGF and Notch in tip and stalk cell selection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(1):a006569. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobbie MW, Roy S, Trudeau K, Munger SJ, Simon AM, Roy S. Reduced connexin 43 expression and its effect on the development of vascular lesions in retinas of diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(7):3758–3763. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger MT, Ramshekar A, Waldschmidt HV, Larsen SD, Bewley MC, Flanagan JM, Antonetti DA. Occludin S471 Phosphorylation Contributes to Epithelial Monolayer Maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36(15):2051–2066. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00053-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Lampugnani MG, Moons L, Breviario F, Compernolle V, Bono F, Balconi G, Spagnuolo R, Oosthuyse B, Dewerchin M, Zanetti A, Angellilo A, Mattot V, Nuyens D, Lutgens E, Clotman F, de Ruiter MC, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R, Lupu F, Herbert JM, Collen D, Dejana E. Targeted deficiency or cytosolic truncation of the VE-cadherin gene in mice impairs VEGF-mediated endothelial survival and angiogenesis. Cell. 1999;98(2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson-Walter EB, Hampton J, Shue E, Geynisman DM, Pillai PK, Sathanoori R, Madden SL, Hamilton RL, Walter KA. Plasmalemmal vesicle associated protein-1 is a novel marker implicated in brain tumor angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(21):7643–7650. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Stahl A, Krah NM, Seaward MR, Joyal JS, Juan AM, Hatton CJ, Aderman CM, Dennison RJ, Willett KL, Sapieha P, Smith LE. Retinal expression of Wnt-pathway mediated genes in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (Lrp5) knockout mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jump DB, Esselman WJ, Busik JV. Inhibition of cytokine signaling in human retinal endothelial cells through modification of caveolae/lipid rafts by docosahexaenoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(1):18–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow BW, Gu C. Gradual Suppression of Transcytosis Governs Functional Blood-Retinal Barrier Formation. Neuron. 2017;93(6):1325–1333. e1323. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke DD, S L, AB Siegel GJ, Albers RW, et al. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. Regulation of Cerebral Metabolic Rate. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AW, Razani B, Schubert W, Williams TM, Wang XB, Iyengar P, Brasaemle DL, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Role of caveolin-1 in the modulation of lipolysis and lipid droplet formation. Diabetes. 2004;53(5):1261–1270. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen M, Elzarrad MK, Seaman S, Zudaire E, Stevens J, Yang MY, Li X, Chaudhary A, Xu L, Hilton MB, Logsdon D, Hsiao E, Stein EV, Cuttitta F, Haines DC, Nagashima K, Tessarollo L, St Croix B. GPR124, an orphan G protein-coupled receptor, is required for CNS-specific vascularization and establishment of the blood-brain barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(14):5759–5764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017192108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins PM. Occludin: one protein, many forms. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(2):242–250. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06029-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Vaz JG, Shakib M, Ashton N. Studies on the permeability of the blood-retinal barrier. I. On the existence, development, and site of a blood-retinal barrier. Br J Ophthalmol. 1966;50(8):441–453. doi: 10.1136/bjo.50.8.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Agalliu D, Zhou L, Kuhnert F, Kuo CJ, Barres BA. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for CNS, but not non-CNS, angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(2):641–646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805165106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Zhou L, Agalliu D, Cahoy JD, Kaushal A, Barres BA. The mouse blood-brain barrier transcriptome: a new resource for understanding the development and function of brain endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2010;468(7323):562–566. doi: 10.1038/nature09513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele LL, Adams RH, Durante DE, Pugh EN, Jr, Philp NJ. Novel distribution of junctional adhesion molecule-C in the neural retina and retinal pigment epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505(2):166–176. doi: 10.1002/cne.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Toro R, Prahst C, Mathivet T, Siegfried G, Kaminker JS, Larrivee B, Breant C, Duarte A, Takakura N, Fukamizu A, Penninger J, Eichmann A. Identification and functional analysis of endothelial tip cell-enriched genes. Blood. 2010;116(19):4025–4033. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Flores L, Gutierrez R, Madrid JF, Varela H, Valladares F, Acosta E, Martin-Vasallo P, Diaz-Flores L., Jr Pericytes. Morphofunction, interactions and pathology in a quiescent and activated mesenchymal cell niche. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24(7):909–969. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, Kasper M, Lohn M, Lauterbach B, Menne J, Lindschau C, Mende F, Luft FC, Schedl A, Haller H, Kurzchalia TV. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293(5539):2449–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnet K, Schulz CU, Meyer Zu Brickwedde MK, Pendl GG, Vestweber D. Junctional adhesion molecule interacts with the PDZ domain-containing proteins AF-6 and ZO-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):27979–27988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulou M, Avramovic N, Klotzsche-von Ameln A, Korovina I, Sprott D, Samus M, Gercken B, Troullinaki M, Grossklaus S, Funk RH, Li X, Imhof BA, Orlova VV, Chavakis T. Endothelial-specific deficiency of Junctional Adhesion Molecule-C promotes vessel normalisation in proliferative retinopathy. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(6):1241–1249. doi: 10.1160/TH15-01-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M. Königthum und staatswesen der alten Hebräer : nach biblischen und talmudischen quellen bearbeitet. Steinamanger: Gedruckt bei J. v. Bertalanffy; 1885. [Google Scholar]

- Elias BC, Suzuki T, Seth A, Giorgianni F, Kale G, Shen L, Turner JR, Naren A, Desiderio DM, Rao R. Phosphorylation of Tyr-398 and Tyr-402 in occludin prevents its interaction with ZO-1 and destabilizes its assembly at the tight junctions. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(3):1559–1569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804783200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaid MF, Kamel H, Chalhoub N, Aziz NA, Ibrahim K, Ben-Omran T, George B, Al-Dous E, Mohamoud Y, Malek JA, Ross ME, Aleem AA. Whole genome sequencing identifies a novel occludin mutation in microcephaly with band-like calcification and polymicrogyria that extends the phenotypic spectrum. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(6):1614–1617. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enge M, Bjarnegard M, Gerhardt H, Gustafsson E, Kalen M, Asker N, Hammes HP, Shani M, Fassler R, Betsholtz C. Endothelium-specific platelet-derived growth factor-B ablation mimics diabetic retinopathy. EMBO J. 2002;21(16):4307–4316. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar MG, Palade GE. Junctional complexes in various epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:375–412. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman GJ, Mullin JM, Ryan MP. Occludin: structure, function and regulation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(6):883–917. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Venema VJ, Venema RC, Tsai N, Caldwell RB. VEGF induces nuclear translocation of Flk-1/KDR, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and caveolin-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256(1):192–197. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey T, Antonetti DA. Alterations to the blood-retinal barrier in diabetes: cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(5):1271–1284. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin-1 and-2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(7):1539–1550. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Hata M, Furuse K, Yoshida Y, Haratake A, Sugitani Y, Noda T, Kubo A, Tsukita S. Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(6):1099–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1993;123(6 Pt 2):1777–1788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Itoh M, Hirase T, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Direct association of occludin with ZO-1 and its possible involvement in the localization of occludin at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(6 Pt 1):1617–1626. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Sasaki H, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. A single gene product, claudin-1 or-2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(2):391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia CM, Darland DC, Massingham LJ, D'Amore PA. Endothelial cell-astrocyte interactions and TGF beta are required for induction of blood-neural barrier properties. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152(1):25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner TA, Stitt AW, Archer DB. Retinal vascular endothelial cell endocytosis increases in early diabetes. Lab Invest. 1995;72(4):439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavard J. Breaking the VE-cadherin bonds. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(1):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Golding M, Fruttiger M, Ruhrberg C, Lundkvist A, Abramsson A, Jeltsch M, Mitchell C, Alitalo K, Shima D, Betsholtz C. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(6):1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, Wolburg H, Redies C. N-cadherin mediates pericytic-endothelial interaction during brain angiogenesis in the chicken. Dev Dyn. 2000;218(3):472–479. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(200007)218:3<472::AID-DVDY1008>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitescu L, Fixman A, Simionescu M, Simionescu N. Specific binding sites for albumin restricted to plasmalemmal vesicles of continuous capillary endothelium: receptor-mediated transcytosis. J Cell Biol. 1986;102(4):1304–1311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotta M, Trani M, Dejana E. VE-cadherin and endothelial adherens junctions: active guardians of vascular integrity. Dev Cell. 2013;26(5):441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenney JR, Jr, Soppet D. Sequence and expression of caveolin, a protein component of caveolae plasma membrane domains phosphorylated on tyrosine in Rous sarcoma virus-transformed fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(21):10517–10521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner B, Lowenkopf T, Apatira D. Identification of a 160-kDa polypeptide that binds to the tight junction protein ZO-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(8):3460–3464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzel D, Yu AS. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(2):525–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallmann R, Mayer DN, Berg EL, Broermann R, Butcher EC. Novel mouse endothelial cell surface marker is suppressed during differentiation of the blood brain barrier. Dev Dyn. 1995;202(4):325–332. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002020402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins J, Gu L, Wittchen ES, Hibbard J, Stevenson BR. ZO-3, a novel member of the MAGUK protein family found at the tight junction, interacts with ZO-1 and occludin. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(1):199–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Phng LK, Gerhardt H. VEGF and Notch signaling: the yin and yang of angiogenic sprouting. Cell Adh Migr. 2007;1(3):133–136. doi: 10.4161/cam.1.3.4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MM, Bastiani M, Luetterforst R, Kirkham M, Kirkham A, Nixon SJ, Walser P, Abankwa D, Oorschot VM, Martin S, Hancock JF, Parton RG. PTRF-Cavin, a conserved cytoplasmic protein required for caveola formation and function. Cell. 2008;132(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirase T, Staddon JM, Saitou M, Ando-Akatsuka Y, Itoh M, Furuse M, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S, Rubin LL. Occludin as a possible determinant of tight junction permeability in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 14):1603–1613. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.14.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman P, Blaauwgeers HG, Tolentino MJ, Adamis AP, Nunes Cardozo BJ, Vrensen GF, Schlingemann RO. VEGF-A induced hyperpermeability of blood-retinal barrier endothelium in vivo is predominantly associated with pinocytotic vesicular transport and not with formation of fenestrations. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21(2):637–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman P, Blaauwgeers HG, Vrensen GF, Schlingemann RO. Role of VEGF-A in endothelial phenotypic shift in human diabetic retinopathy and VEGF-A-induced retinopathy in monkeys. Ophthalmic Res. 2001;33(3):156–162. doi: 10.1159/000055663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman P, Hoyng P, vanderWerf F, Vrensen GF, Schlingemann RO. Lack of blood-brain barrier properties in microvessels of the prelaminar optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(5):895–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Blakeslee B, Laughlin SB. The intracellular pupil mechanism and photoreceptor signal: noise ratios in the fly Lucilia cuprina. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1987;231(1265):415–435. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S, Yang H, Chan-Ling T. Vascularization of the human fetal retina: roles of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(5):1217–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenouchi J, Furuse M, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Tsukita S, Tsukita S. Tricellulin constitutes a novel barrier at tricellular contacts of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(6):939–945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]