Highlights

-

•

About 5% of patients experience long-term gastric conduit retention.

-

•

Two patients with hybrid and total minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy experienced long-term retention of the conduit.

-

•

Initial too wide hiatal opening or a combination of a redundant conduit and a too narrow hiatus led to conduit retention.

-

•

Reoperation involved open thoracoabdominal access for mobilization, reduction and diaphragmatic fixation of the herniated conduit.

-

•

One patient had an excellent result whilst the other improved despite a limited degree of reherniation of the conduit.

Abbreviations: HE, hybrid esophagectomy; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; BMI, body mass index

Keywords: Cancer, Esophagectomy, Conduit retention, Conduit herniation, Hiatal hernia

Abstract

Introduction

Following esophagectomy about 5% of patients experience long-term gastric conduit retention. We report two patients with surgical correction for this problematic condition. This case series is a retrospective, non-consecutive single center report.

Presentation of cases

A slender female aged 76 (patient 1) and an obese man aged 69 (patient 2) with esophageal cancer, underwent hybrid and total minimally invasive Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy, respectively. The conduit was tubularized, and the stapled anastomosis located above carina. The crura were divided in patient 1. Contrast enema revealed a straight (patient 1) or redundant (patient 2) thoracic conduit. Conduit retention in patient 1 began after 47 months. After 61 months reoperation was performed with open thoracoabdominal access for mobilization, abdominal reduction and diaphragmatic suture fixation of the herniated conduit. Symptoms improved and oral nutrition is still sufficient after 8 months.

Patient 2 had clinically significant retention after 15 months, despite using pyloric Botox injection and expandable metal stenting. At laparoscopic reoperation after 27 months a partial conduit mobilization and refixation were unsuccessful, but an accidental colonic hiatal hernia was taken down. After 28 months a second reoperation was performed, similar to patient 1. Fifteen months afterwards the patient still ate sufficiently, but a limited double reherniation had occurred.

Discussion

Long-term retention post-esophagectomy often start with an initial redundant conduit, that can increase from food-induced stretching and declive emptying against gravity. A wide hiatal opening probably also predispose to conduital herniation.

Conclusions

Conduit retention improved after mobilization, reduction and its hiatal fixation. A too wide or narrow hiatal opening must be avoided to prevent herniation.

1. Introduction

Delayed gastric conduit emptying after esophagectomy involve 15–30% of the patients [1,Rove et al.]. Treatment options are mainly postoperative pneumatic pyloric balloon dilation [2], [3] but also perioperative intramuscular quadrant injection of Botulinum toxin [4], both with about 96% success rates.

However, up to 5% of the patients suffer from long-term conduit dysfunction [5] with severe symptoms of retention leading to malnutrition, weight loss, reflux-induced pneumonia and dependency of supplemental nutrition. The debilitating symptoms of conduit dysfunction may develop from months to years after esophagectomy and the end-stage treatment that may alleviate their symptoms is surgical correction. The major ultimate findings, as reported [5], in patients with development of conduit retention over time, were demonstration of redundant conduit with the horizontal portion lying on the right diaphragm below its hiatal outlet, creating obstruction of conduital emptying into duodenum. Reasons for redundant conduit may be i) an overlooked redundancy at initial operation, ii) mechanichal obstruction to emptying, iii) twisted conduit and a iv) sigmoid shaped conduit with obstruction solely because of dysmotility. A hiatal hernia, usually in the left chest, may also occur combined with conduit retention. In two large studies [1], [5] this combination was evident in 3 of 22 (13.6%) and 2 of 7 (29.6%) patients. In our record from 2007 to 13 of 109 hybrid esophagectomies (HE) and from 2013 to 15 of 110 total minimally invasive esophagectomies (MIE) we have reoperated one patient from each period (0.91%) for gastric conduit retention, also including a hiatal hernia in the MIE group.

We hereby report their surgical treatment course and discuss etiology and potential prophylactic measures for minimizing occurrence of this devastating clinical condition.

2. Case presentations

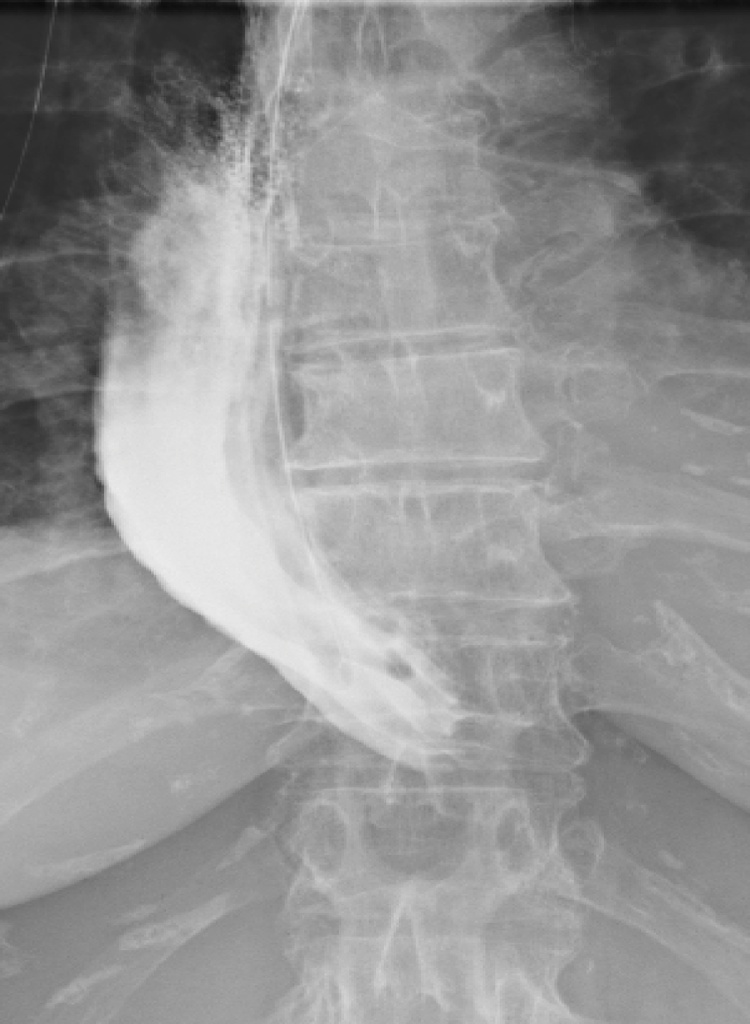

Patient 1 was a slender female aged 76 with no comorbidity beyond hip replacement surgery for arthrosis. She was diagnosed with cancer in the lower third of esophagus and underwent in January 2012 a hybrid esophageal Ivor-Lewis resection via laparoscopy and open right thoracotomy in 7. intercostal space. The stomach was mobilized and both diaphragmatic crura were divided in order to achieve wide enough hiatal opening for thoracic translocation of the whole stomach, that underwent stapled resection into a tubularized a conduit of width 3–5 cm. The conduit that was not sutured to the diaphragm. An end-to-side posterior mediastinal circular anastomosis was made right above the tracheal bifurcation. Lymphadenetomy involved nodes of the lower and middle mediastinum. Postoperative X-ray oral contrast enema at day 7 (Fig. 1) revealed a straight intrathoracic conduit and an intact anastomosis. The patient received antibiotics for pneumonia and was discharged from hospital at postoperative day 21. Histology revealed squamous cell carcinoma without lymph node metastases (pT1bN0M0).

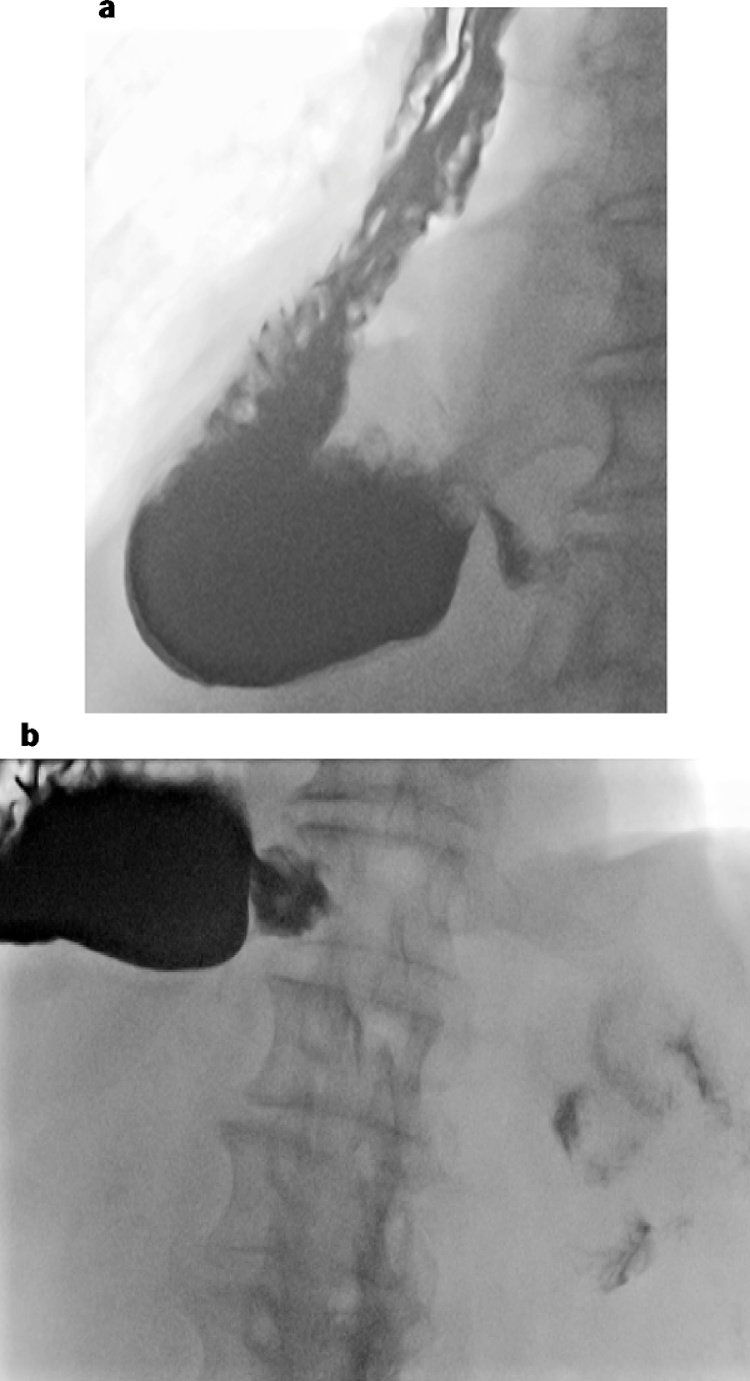

Fig. 1.

An oral contrast enema at postoperative day 7 after esophagectomy showed a straight gastric conduit in the right hemithorax (patient 1).

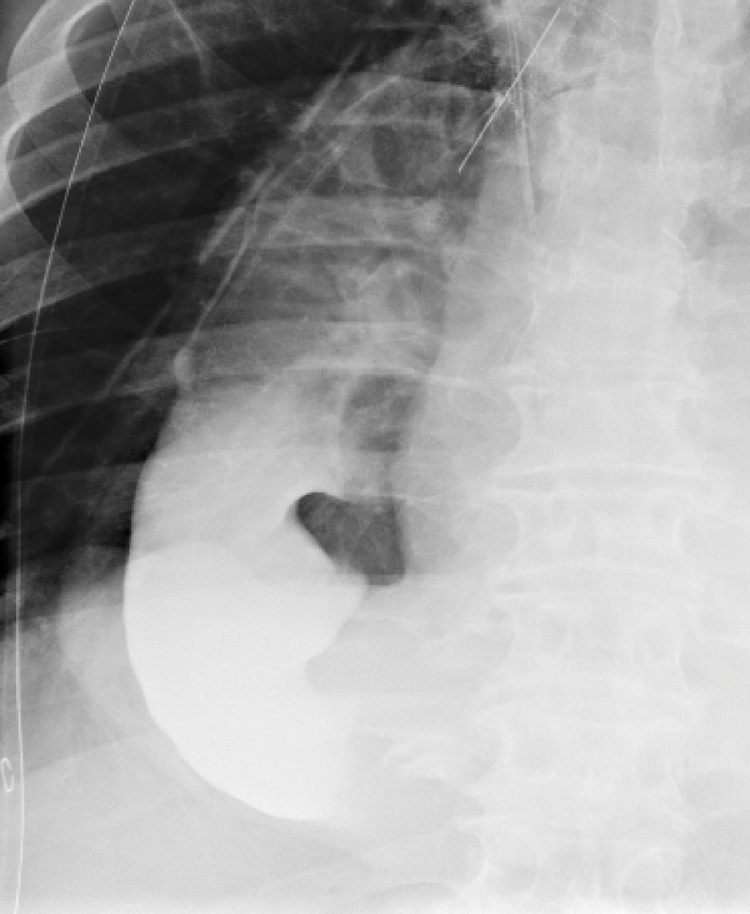

From 47 months postoperatively the patient suffered from increasing dysphagia, weight loss (20 kg) and malnutrition (BMI 14.6 m2/kg), that 9 months later necessitated acute hospital admission. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a dilated and filled conduit located in the right hemithorax (Fig. 2). Gastroscopy revealed retention in the conduit but open passage into duodenum. The antral part of the conduit seemed somewhat twisted. The symptoms of dysphagia and conduit retention persisted and the patient received both enteral and parenteral nutrition for three months. An oral contrast X-ray enema after 60 months demonstrated a redundant conduit with its lowermost point lying on the right diaphragm and with herniation of pylorus right above the esophageal hiatus (Fig. 3). There was delayed passage of contrast into the duodenum. In this situation the patient was not able to feed herself sufficiently. After 4 months of aided feeding she was considered fit enough for reoperation, 61 months after the initial surgery.

Fig. 2.

A CT scan demonstrated a dilated and filled conduit with the declive part lying on the right diaphragm (patient 1).

Fig. 3.

Prior to reoperation an esophagram demonstrated pyloric dislocation above the hiatus, a redundant conduit partly lying on the diaphragm and delayed emptying of contrast into the duodenum (patient 1).

Mobilization and repositioning of a non-twisted redundant and dilated conduit back into the abdomen by division of adhesions to the mediastinum and hiatus as well as upper abdomen, was performed through a right sided thoracotomy and an upper mini laparotomy. The straightened and moderately dilated conduit, with width 4–6 cm, was fixed with interrupted Tycron® 0 sutures to the right hiatal edge (3 sutures) from the thoracic side and to the neighbouring left diaphragm (2 sutures) from the abdominal side. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was able to eat and drink within a few days and discharged from hospital after 12 days. Oral contrast enema (Fig. 4) and gastric emptying test (C-Octanic acid breath test) 2.5 months after surgery were normal, demonstrating a straightened intrathoracic conduit. The patient has had a weight gain of 6 kg, and after 8 months oral food intake still is sufficient.

Fig. 4.

Following reoperation an esophagram demonstrated a straightened conduit with the pylorus reduced below the hiatus and efficient emptying of contrast into the duodenum (patient 1).

Patient 2 was an obese man (BMI 33.3) aged 69 with normal heart and lung function. He was diagnosed with a lower esophageal cancer in Barrett’s esophagus. After neoadjuvant chemoradiation [6] total MIE in the left lateral position was performed with a stapled circular anastomosis (esophago-gastrostomy) at a level just above the tracheal bifurcation. The tubularized gastric conduit with up to 6 cm width was not fixed to the intact diaphragmatic crura. Lymphadenectomy was performed in the lower and middle mediastinum. As for case 1, the anastomosis was intact at day 7 but with a redundant conduit (Fig. 5). The patient was discharged from hospital at day 18 following an uneventful course. Histology revealed adenocarcinoma with a R1 resection due to tumorinfiltration in the circumferential resection margin and lymph node metastases (pT3N1Mx). After only one course of chemotherapy (EOX; Epirubicin, Oxaliplatin, Xeloda) terminated due to cardiac ischemia, the patient still is free from cancer recurrence after 43 months observation.

Fig. 5.

In patient 2 postoperative oral contrast enema showed a redundant conduit in the right hemithorax (patient 2).

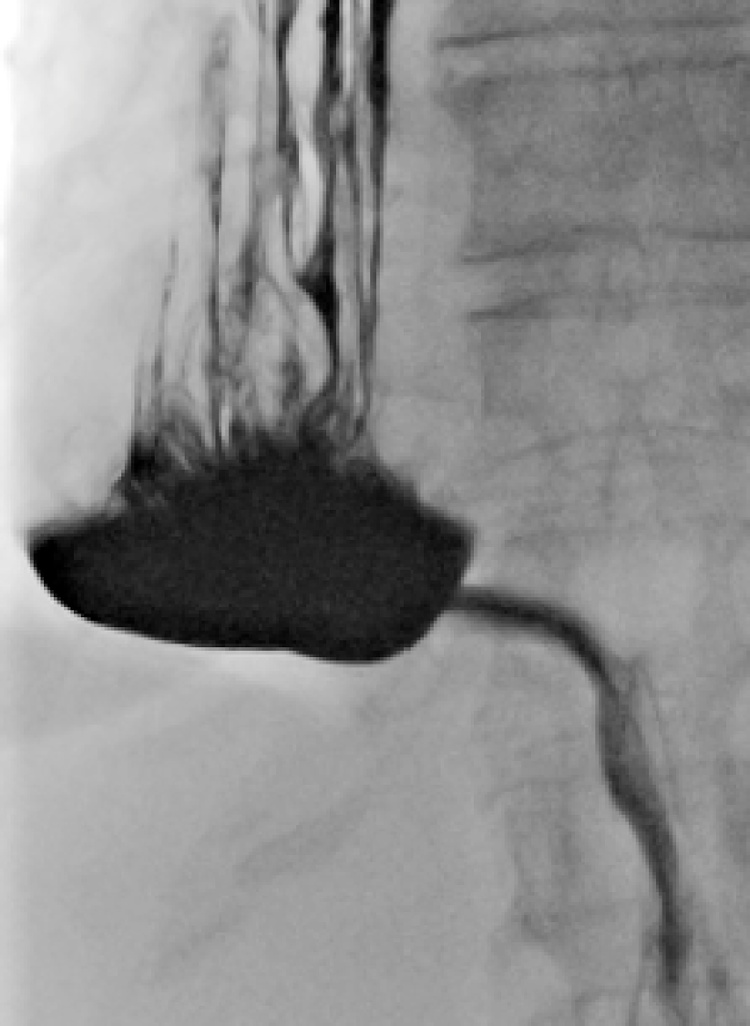

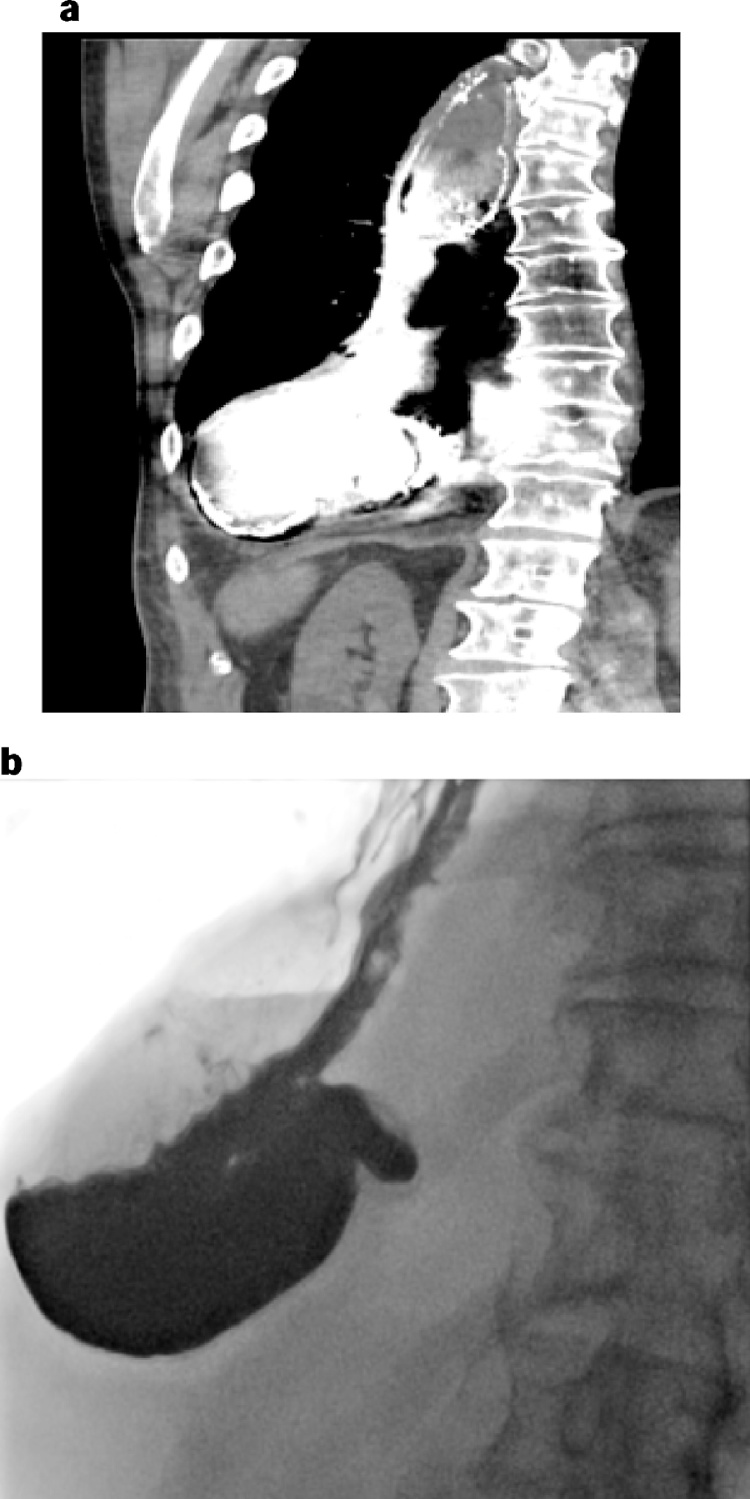

Ingestion of food with initial weight gain was satisfactory until 15 months postoperatively. At this time the patient gradually experienced increasing symptoms of gastric conduit retention, including hospital admissions for aspiration-induced pneumonia. Pyloric injections of botulinum toxin did not alleviate the symptoms. The patient was dependent on both enteral and parenteral nutrition, using mainly a nasoenteral doublelumen tube for aspirations of contents from the conduit and simultaneously feeding into jejunum. After 27 months a CT scan (March 16) of the chest and upper abdomen confirmed a redundant conduit with a relatively long distal segment, incuding the pylorus, lying on the diaphragm with only minor passage of contrast into the abdomen (Fig. 6a). An oral contrast enema after 29 months confirmed these findings (Fig. 6b), but now with full retention as there was no passage of contrast into the abdomen.

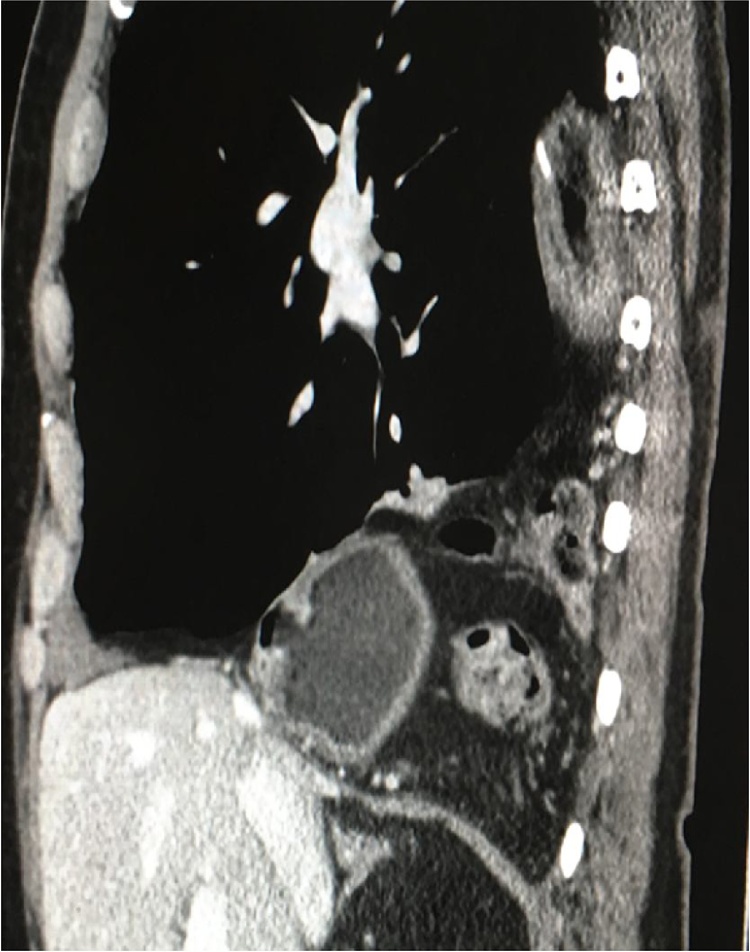

Fig. 6.

A partially herniated redundant conduit and pylorus with a considerable horizontal portion lying towards the diaphragm as judged by a CT scan (a) and oral contrast enema (b) (patient 2).

The patient was persistently unable to eat and drink and was gravely depressed. In a multidisiplinary meeting it was decided to offer surgical correction of the redundant conduit. After 28 months the patient underwent the first reoperation laparoscopically with partial transhiatal mobilization, reduction and fixation of the conduit to the diaphragmatic crura with 6 Ethibond® 1 sutures. A 14 Fr jejunal feeding catheter was also installed. In addition, a transhiatal herniation of transverse colon to the left chest was easily reduced into the abdomen. A transient improvement of oral intake followed but the patient‘s gastric conduit retention reoccurred without opportunity for eating and daily intake of only minor fluid volumes. Therefore, 29 months after the initial operation a 12.5 cm long fenestrated Wall stent was centrally placed in the pylorus and further sutured to the duodenum by laparoscopy, thereby minimizing risk for stent migration. Unfortunately, the stent had to be removed endoscopically after 9 days due to dislocation into the gastric conduit. The patient’s clinical symptoms were still unresolved. Three weeks later the patient underwent a third reoperation in which 6–8 cm of redundant conduit was reduced into the abdomen via a right lower thoracotomy and an upper mini laparotomy. Some adhesions were dissected, and the straightened tubelike conduit was fixed to the oesophageal hiatus and crura by interrupted Tycron® 1 sutures. Within a few days the patient could eat and drink carefully without any need for additional nutrition to maintain adequate caloric intake (2000 kcal/24 h). The patient had no symptoms of retention and was discharged from hospital after 13 days.

Six months after the last reoperation the patient was thoroughly examined. A gastric emptying test (13C-octanic acid breath test) was within the normal range. Endoscopy proved an open conduit with a slight degree of retention, assumed mainly due to vagal denervation. The first oral contrast enema identified a partial recurrence of conduit herniation (Fig. 7a) but still acceptable emptying or oral contrast into the duodenum (Fig. 7a and b). However, after 8 months a limited recurrent lower herniation of the transverse colon 8 cm into the posterior mediastinum and to the left hemithorax was detected on a CT scan (Fig. 8). Current status after 15 months is that the patient has gained 7 kg of weight, has no persistent retention or pain, and can still eat and drink adequately without supplemental nutrition. However, he must be careful to avoid heavy meals and to use laxatives twice daily.

Fig. 7.

Six months after last reoperation there was a partial recurrence of conduit herniation (a) but still acceptable emptying or oral contrast into the duodenum (a and b) (patient 2).

Fig. 8.

Thoracic reherniation of the conduit and pylorus (small arrow) and of the transverse colon posteriorly (broken arrow) as demonstated by a coronal CT scan (patient 2).

3. Discussion

We have outlined the treatment of two patients with the rare but debilitating complication of long-term gastric conduit retention from development of an increasingly redundant conduit. Potential etiologies and measures to avoid this condition will be discussed.

An unavoidable consequence of esophagectomy is impaired motility of the tubularized gastric conduit because of vagal denervation and removal of the gastric pacemaker neurons located to the lesser curve [7]. However, the effect of vagotomy was probably negligible since both patients had a gastric emptying test (13C-octanic acid breath test) within the normal range after the reoperations. Further, none of our patients suffered from any organic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus or neuromuscular disease, that potentially could influence motility patterns. At initial esophagectomy, the conduit was not routinely sutured to the diaphragm, neither in these two cases nor in our series of 219 MIE and HE from 2007 to 2015. This practice was similar to one [1] but contrary to another major study [5], reporting gastric conduit revision surgery in 8 of about 400 patients (2.0%) from 2008 to 2015 and 22 of 1075 patients (2.0%) from 1995 to 2007, respectively. Thus, whether conduit fixation to the diaphragm should be made at initial surgery in order to avoid development of a redundant conduit, still is unresolved.

In patient 1 with HE, both crura were divided in order to facilitate thoracic translocation of the stomach. A subsequent narrowing of the hiatus by posterior crural approximation with sutures, potentially could have decreased the risk of herniation of the conduit into the chest. The patient was reoperated with open thoracoabdominal surgery for adequate access, mobilization and abdominal repositioning of the conduit prior to fixation with interrupted non-resorbable sutures. The clinical result after 8 months is satisfactorily without need for supplemental nutrition and admission to hospital.

Patient 2 that underwent MIE had a more complex history including neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy because of a R1 resection in the circumferential resection margin. Compared to patient 1 (Fig. 1) the initial postoperative contrast enema already showed a lax and redundant conduit (Fig. 5). This difference could partly explain the earlier development of retention (15 months versus 47 months) in this patient. Laparoscopic partial transhiatal mobilization and fixation of the conduit was not sufficient to resolve the retention, and a primarily unknown transhiatal colonic hernia was easily repositioned. Also the following procedure of transpyloric stenting failed because of proximal stent migration, despite its fixation to duodenum by laparoscopic suture. As for patient 1, the final reoperation was performed by the same type of surgical intervention through an open access. Despite meticulous suture for hiatal alignment of the conduit a limited conduital and colonic reherniation occurred about half a year after the reoperation (Fig. 8). However, the clinical improvement persisted, granted the patient used laxantia and avoided heavy meals in order to avoid signs of retention.

In the largest series [5] of 24 hiatal hernias diagnosed mean 32 months after esophagectomy, including 3 cases on redundant conduit, colon was the most frequently herniated organ (92%) followed by small bowel (21%). The herniation, as in patient 2, was usually (87%) between the left side of the conduit and the left crus and into the left chest. The reason may be less formation of adhesions along the left crus that is in contact with the serosal surface of the conduit on the major side, contrary to the staple line directed to the right side that may irritate tissue and induce formation of adhesions with the right crus. Operative repair was performed in 22 of these patients, and mostly (59%) by a meshless suture based on mobilization and approximation of the crura without tension by unresorbable sutures behind the conduit. With a median follow-up of 13 months the reherniation rate in this large series was 29% and similar without or with use of a mesh (30% vs 27%).

It has been shown in two randomized control trials [8], [9] that formation of a gastric tube of diameter 3–4 cm versus whole stomach substitute, gave a better functional result, including less dysphagia and reflux as well as improved quality of life in patients that underwent esophagectomy. Thus, there should be uncontroversial to prefer a circular and relatively narrow gastric tube in these patients [10] although the optimal width is still not known. On the other hand, it has not been demonstrated that a pyloric drainage procedure like pyloroplasty and pyloromyotomy has reduced the delayed gastric emptying in the postoperative phase.

As reported [5] the etiology behind the development of a redundant conduit was considered to be due to mechanichal obstruction at the level of the hiatus in 54% of the patients. Accordingly, a major challenge is to harmonize the size of the hiatus to the size of the conduit to the individual patient, in order to reduce a free hiatal opening that may increase the risk for thoracic dislocation of the conduit (Fig. 1) and other visceral organs. In addition, it is also mandatory to avoid an initial lax conduit that may predispose to later dilatation and increased redundancy of the conduit (Fig. 5). A general prophylactic advice to the patient post esophagectomy, is to avoid extensive meals that burdens the conduit with dilatation and stretching because of increased filling and likelihood for retention from outflow obstruction of solids and liquids into the abdomen. This is relevant when the horizontal part of the conduit is placed on the right diaphragm beneath the level of the hiatus and emptying is reduced by gravity.

An interesting treatment for refractory delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy in patients with a sufficiently open hiatus and without a concurrent redundant conduit, may be an open transabdominal Heineke-Mikulicz rescue pyloroplasty that was performed after mean 13 months (range, 3–22) in a retrospective study of 13 patients [11]. All patients gained weight and the treatment was defined as a success for 9 of these patients (69.2%), including increased gastric emptying, less vomiting and improved mental and physical status.

Ultimately, in extremely rare cases with a dysfunctional conduit despite surgical revision, other more complicated surgical options must be considered, using colon or jejunum as interponates. An interesting recently described technique [12] used in 4 patients 2–11 years after esophagectomy complicated by esophagogastric reflux and conduit retention. An antrectomy including pylorus with complete duodenal diversion was performed with sparing of the proximal segment of the conduit, including obligate preservation of the gastroepiploic vessels. Then a Roux-en-Y reconstruction with a gastrojejujonstomy and a 60 cm more caudad jejunojejunostomy. The major challenge of the operation was to preserve the right gastroepiploic vessels supplying the remaining conduit. The results were promising as two patients were asymptomatic and two improved after mean 17.5 months (range, 3–35). As this method is technically challenging the patient should not be operated without the participation of a surgeon with experience in this procedure.

Although the hiatal hernia reoccurred in patient 2, after revisional surgery both patients showed complete resolution or improvement of their debilitating symptoms induced by long-term conduit retention. The patients enjoy food intake and have not been dependent on supplemental nutrition that previously demanded regular hospital admissions.

4. Conclusions

Long-term conduit retention after esophagectomy is a serious complication occurring in up to 5% of the patients. Major complications are severe reflux leading to episodes of aspirational pneumonia, chronic weigth loss and malnutrition from insufficient oral nourishment. We report two patients who developed herniation of the conduit, that was interpreted to be related to either an excessively wide hiatus (patient 1) or an initial redundant conduit (patient 2). The treatment was mobilization, repositioning and hiatal fixation of the conduit. The result was excellent in patient 1 and acceptable in patient 2, despite a limited reherniation of both the conduit and the colon into the chest. In order to minimize this complication the initial conduit should be straight and not curved, and the hiatal opening calibrated to the right diameter. Accordingly, a reherniation can be caused by sliding through a wide hiatus or by conduital stretching in a narrow hiatus. Ultimately, surgery is the only beneficial treatment option in these patients.

Materials and methods

This work has been reported in line with the PROCESS CHECKLIST [13].

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest in regards of writing this article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This case series is not within the mandate for the regional ethical committee.

Consent

We have obtained signed written informed consent from both our patients.

Authors contribution

Ingvild Farnes has written the case series and included relevant figure legends highlighting and picturing the two separate cases.

Egil Johnson has evaluated the case series and contributed with close co-operation in outlining, writing and inclusion of relevant information and graphics.

Hans-Olaf Johannessen has contributed to the overall outlining of this case series.

Guarantor

Egil Johnson is the Guarantor of this project. He accepts full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study and the decision to publish.

Contributor Information

Ingvild Farnes, Email: infarn@ous-hf.no, vildafa@hotmail.com.

Egil Johnson, Email: egil.johnson@medisin.uio.no.

Hans-Olaf Johannessen, Email: uxhojo@ous-hf.no.

References

- 1.Rove J.Y., Krupnick A.S., Baciewicz F.A., Meyers B.F. Gasric conduit revision postesophagectomy: management of a rare complication. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017;(April):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.04.012. pii: S0022-5223(17)30699-2. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanuti M., DeDelva P., Morse C.R., Wright C.D., Wain J.C., Gaissert H.A., Donahue D.M., Mathisen D.J. Management of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy with endoscopic balloon dilatation of the pylorus. Ann. Thor. Surg. 2011;91(4):1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maus M.K.H., Leers J., Herbold T., Bludau M., Chon S.H., Kleinert R., Hescheler D.A., Bollscwuler E., Hölscher A.H., Schäfer H., Alakus H. Gastric outlet obstruction after esophagectomy: retrospective analysis of the effectiveness and safety of postoperative endoscopic pyloric dilatation. World. J. Surg. 2016;40(10):2405–2411. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3575-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin J.T., Federico J.A., McKelvey A.A., Kent M.S., Fabian T. Prevention of delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy: a single center’s experience with botulinum toxin. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2009;87(6):1708–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kent M.S., Luketich J.D., Wilson T., Churilla P., Federle M., Landreneau R., Alvelo-Rivera M., Schuchert M. Revisional surgery after esophagectomy: an analysis of 43 patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008;86(3):975–983. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro J., van Lanschot J.J.B., Hulshof M.C.C.M., van Hagen P., van Berge Henegouwen M.I., Wijnhoven B.P.L., van Laarhoven H.W.M., Nieuwenhuijzen G.A.P., Hospers G.A.P., Bonenkamp J.J., Cuesta M.A., Blaisse R.J.B., Busch O.R.C., Ten Kate F.J.W., Creemers G.M., Punt C.J.A., Plukker J.T.M., Verheul H.M.W., Bilgen E.J.S., van Dekken H., van der Sangen M.J.C., Rozema T., Biermann K., Beukema J.C., Piet A.H.M., van Rij C.M., Reinders J.G., Tilanus H.W., Steyerberg E.W., van der Gaast A., CROSS study group Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collard J.M., Romagnoli R., Otte J.B., Kestens P.J. The denervated stomach as an esophageal substitute is a contractile organ. Ann. Surg. 1998;227(1):33–39. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199801000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C., Wu Q.C., Hou P.Y., Zhang M., Li Q., Jiang Y.J., Chen D. Impact of the method of reconstruction after oncologic oesophagectomy on quality of life—a prospective, randomised study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011;39(1):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bemelman W.A., Taat C.W., Slors J.F.M., van Lanschot J.J., Obertop H. Delayed postoperative emptying after esophageal resection is dependent on the size of the gastric substitute. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1995;180(4):461–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akkerman R.D., Haverkamp L., van Hillegersberg R., Ruurda J.P. Surgical techniques to prevent delayed gastric emptying after esophagectomy with gastric interposition: a systematic review. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014;98(4):1512–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta J., Williams N.N., Conway R.G., Dempsey D.T., Morris J.B. Rescue pyloroplasty for refractory delayed gastric emptying following esophagectomy. Surgery. 2014;156(2):290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Journo X.B., Martin J., Gaboury L., Ferraro P., Duranceau A. Roux-en-Y diversion for intractable reflux after esophagectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008;86(5):1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agha Riaz A., Fowler Alexander J., Rajmohan Shivanchan, Barai Ishani, Orgill Dennis P., for the PROCESS Group Preferred reporting of case series in surgery; the PROCESS guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]