Abstract

The successful transfer of para-hydrogen-induced polarization to 15N spins using heterogeneous catalysts in aqueous solutions was demonstrated. Hydrogenation of a synthesized unsaturated 15N-labeled precursor (neurine) with parahydrogen (p-H2) over Rh/TiO2 heterogeneous catalysts yielded a hyperpolarized structural analogue of choline. As a result, 15N polarization enhancements of over 2 orders of magnitude were achieved for the 15N-labeled ethyltrimethylammonium ion product in deuterated water at elevated temperatures. Enhanced 15N NMR spectra were successfully acquired at 9.4 and 0.05 T. Importantly, long hyperpolarization lifetimes were observed at 9.4 T, with a 15N T1 of ∼6 min for the product molecules, and the T1 of the deuterated form exceeded 8 min. Taken together, these results show that this approach for generating hyperpolarized species with extended lifetimes in aqueous, biologically compatible solutions is promising for various biomedical applications.

Introduction

Hyperpolarization—the creation of highly nonequilibrium nuclear spin polarization—has been investigated for years as a way to dramatically improve the detection sensitivity of NMR and MRI.1−8 Although many hyperpolarization methods have been developed, dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (d-DNP)9,10 has become increasingly dominant for biomedical applications because of advanced technology enabling the preparation of hyperpolarized (HP) nuclear spins within a wide range of chemical and biological systems, including metabolic MRI contrast agents now under investigation in clinical trials.11−13 However, the high costs and infrastructure associated with d-DNP technology, combined with relatively slow production rates, present a challenge for many potential applications.

Approaches exploiting para-hydrogen-induced polarization (PHIP)14−17 could be attractive alternatives because of their dramatically lower costs and instrumentation demands, much greater hyperpolarization rates (minutes to seconds, even allowing continuous agent production), and potential for scalability. In “traditional” PHIP,15,18 the pure spin order from parahydrogen (p-H2) gas is transferred to a molecular substrate via the pairwise hydrogenation of asymmetric unsaturated bonds, a process that is typically facilitated with a catalyst. Key recent PHIP developments for biomedical applications include the demonstration of PHIP in aqueous media19−25 and PHIP using heterogeneous catalysts (HET-PHIP).26−30 The latter approach enables facile separation of the catalyst from the target molecule and, hence, the potential preparation of “pure” HP agents and catalyst reuse. However, also of great importance is the transfer of spin order from the nascent protons to substrate heteronuclei (e.g., 13C), providing greater hyperpolarization lifetimes compared to 1H spins. 13C hyperpolarization via PHIP has been achieved via both RF-driven polarization transfer31−36 and polarization transfer in a magnetic shield (i.e., field cycling),37,38 an approach that very recently has been extended to HET-PHIP conditions to produce aqueous solutions of highly polarized 13C-containing molecules free from the catalyst.27,39

Translation of this approach to 15N spins could have many advantages; indeed, Aime and co-workers have recently demonstrated 15N hyperpolarization of propargylcholine-15N via homogeneous PHIP and field cycling in a mixture of acetone and methanol or in water.40 In addition to greatly increasing agent diversity, agents with HP 15N spins can be spectrally sensitive to the local biochemical environment.41−43 Importantly, 15N T1 values are often considerably longer than corresponding 13C values,43−45 thereby enabling longer hyperpolarization storage (either for direct readout or for transfer to 1H for more sensitive detection);46−52 such T1 values are expected to be even longer at lower magnetic fields.53,54

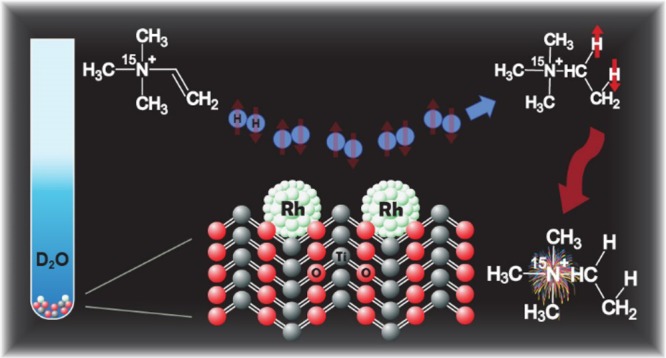

Herein, we report 15N NMR hyperpolarization of a structural analogue of choline via heterogeneous, aqueous-phase hydrogenation of 15N-trimethyl(vinyl)-ammonium (i.e., neurine-15N) bromide over solid Rh/TiO2 catalysts. The PHIP-derived 15N nuclear spin polarization achieved in these experiments is the first reported to date involving heterogeneous catalysis and yielded 15N enhancements of ∼2 × 102-fold and a long relaxation time of ∼350 s at 9.4 T; deuterating the substrate yielded weaker enhancements but a longer relaxation time (15N T1 ≈ 500 s). Finally, significant signal enhancement is shown for the first time to enable detection at low (0.05 T)55 magnetic field of the 15N resonance for molecules polarized using PHIP. For most of the heterogeneous hydrogenation reactions in this work, hydrogen gas was used with 50% p-H2 enrichment (the normal room-temperature ratio of para- to ortho-hydrogen is 25/75) prepared with a home-built generator (more details concerning experiments, chemical synthesis, and characterization are provided in the Supporting Information (SI)).

Results and Discussion

In one experiment, freshly produced p-H2 was bubbled at 90 psi into a medium-wall NMR tube (using a previously developed setup)27,39 containing the target substrate (neurine-15N bromide) and the heterogeneous catalyst Rh/TiO2 in water (D2O) at 90 °C, causing the unsaturated substrate to be hydrogenated via pairwise addition. The reaction was performed under ALTADENA56 conditions (i.e., wherein the hydrogenation reaction was performed outside of the magnet at low field), and results are shown in Figure 1 (see also Figures S5 and S8). In order to effect the transfer of spin order from nascent 1H substrate spins to 15N, the hydrogenation reaction was performed by using a magnetic shield, similar to the recently reported procedure—also know as the magnetic field cycling (MFC) approach,27,57−59 but in our case, the hydrogenation reaction was carried out directly in the magnetic shield. The level of polarization achieved is strongly dependent upon the speed of the sample transfer from the low (micro-Tesla) field to the Earth’s field;40 therefore, to avoid related issues, the hydrogenation reaction was performed directly in the magnetic shield, and only after the termination of p-H2 bubbling was the sample quickly transferred to the high-field NMR for analysis. A strong 15N NMR signal was observed for the HP product (Figure 1B); however, no 15N signal was observed prior to p-H2 bubbling (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) 15N NMR spectrum of a 0.25 M 15N-neurine substrate in the presence of 1.0% Rh/TiO2 before reaction with p-H2 in D2O, recorded with eight scans and a 30 s repetition delay; no signal of reactant is observed at 58 ppm under these conditions. 15N NMR spectrum of the hyperpolarized product using the same acquisition parameters as those used for spectrum acquisition shown in (A) but taken with 1 scan after transfer of spin order to 15N, achieved with 30 s 50%-enriched p-H2 bubbling inside of the magnetic shield. (C) Same as (B) but with hydrogenation occurring over 23.2% Rh/TiO2. HP 15N spectra are shown with an absorptive phase (i.e., sharing the same phase as a thermally polarized 15N sample); note that the field cycling was not optimized for polarization transfer.

This 15N NMR enhancement was achieved using Rh/TiO2 catalyst with 1.0% Rh loading. Importantly, utilization of Rh/TiO2 solid catalyst for heterogeneous PHIP60,61 can, in principle, allow one to alter the conversion rate by varying the Rh fraction62 of the catalytic material without decreasing the achieved polarization level of the products.27 To investigate this possibility for the present reaction, a second Rh/TiO2 catalyst with 23.2% Rh loading was also used (Figure 1C). Although an enhanced 15N signal of the product is observed with the 23.2% Rh/TiO2 catalyst, the signal is ∼3.7-fold weaker than that observed with the 1.0% Rh catalyst. The explanation comes from the corresponding 1H HET-PHIP spectra (Figure S8), which indicate that, while the 23.2% Rh catalyst does indeed yield much higher reaction rates (in fact, providing essentially complete conversion of the substrate in 30 s), a smaller 1H polarization enhancement is achieved, giving rise to the weaker 15N enhancement in Figure 1 (possibly reflecting either reduced pairwise H2 addition or different 1H relaxation of species adsorbed onto catalyst particles). Thus, the 1.0% Rh catalyst was used for the subsequent experiments in this work. In any case, these observations are the first reported to date for hyperpolarization of 15N-containing molecules via heterogeneous catalysis with 15N polarization derived from the spin order from p-H2.

The effects of substrate deuteration and increased p-H2 fraction on 15N signal enhancement were also separately investigated. Deuteration has previously been shown to increase heteronuclear (e.g., 13C) T1 in the context of PHIP63,64 and DNP.65 Here, following successful observation of 1H HET-PHIP with the fully deuterated substrate (neurine-15N-d12 bromide; see the SI for synthesis and Figure S9 for spectra), the approach described above was used to demonstrate 15N enhancement of the product in the aqueous phase following heterogeneous hydrogenation (Figure 2A). However, the intensity of this 15N line was slightly lower than that of the fully protonated substrate studied under the same conditions (Figure 2B). This reduced 15N enhancement with deuterated substrates is analogous to that observed with 15N SABRE-SHEATH (Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange in SHield Enables Alignment to Heteronuclei)66 and likely reflects either enhanced 15N relaxation in the μT regime (i.e. within the magnetic shield) or a more direct loss of spin order into the 2H spin degrees of freedom under those conditions.

Figure 2.

(A) Single-shot 15N NMR spectrum of the fully deuterated substrate (0.125 M) solution in D2O obtained after 30 s of p-H2 bubbling (50% p-H2 fraction) and polarization transfer to 15N using the magnetic shield. (B) Same as (A) but with the protonated substrate (0.125 M). (C) Same as (B) but with an 80% p-H2 fraction.

On the other hand, use of a greater p-H2 fraction with the protonated substrate did yield an expected increase in 15N signal enhancement (Figure 2C). For this experiment, the p-H2 fraction was increased to 80% using a cryocooler-based p-H2 generator operating at a temperature lower than the 77 K of lN2 (see the SI for details). Increasing the ratio of para- to ortho-H2 from ∼50/50 (Figure 2B) to ∼80/20 (Figure 2C) yielded an improvement in the product’s 15N signal enhancement by nearly 3-fold, approaching the full 3-fold increase that would be theoretically expected if 100% p-H2 had been used. Taking the results from Figures 1 and 2 together, the greatest signal enhancement was achieved using 80% p-H2 on the protonated substrate in the presence of 1.0% Rh/TiO2.

In PHIP, quantification of the sensitivity gain provided by the polarization level requires not only comparison with a signal from a thermally polarized sample but also an estimation of the efficiency of the hydrogenation reaction (and hence, the concentration of the product) at the time of detection. Here, the HP 15N signal was compared to the thermally polarized signal obtained from a 3.2 M 15NH4Cl aqueous solution. Note that the spectrum in Figure 2C was obtained after the first 30 s of p-H2 bubbling; comparison with thermal 15N (and 1H) spectra obtained with different bubbling times allowed the conversion level of the reagent to the product to be estimated at ∼10% (see Figure S10C). Therefore, the concentration of the product in Figure 2C is approximately 0.0125 M, yielding a corresponding 15N signal enhancement of ε ≈ 2 × 102 (attempts to detect polarization of 15N nuclei at natural abundance were unsuccessful).

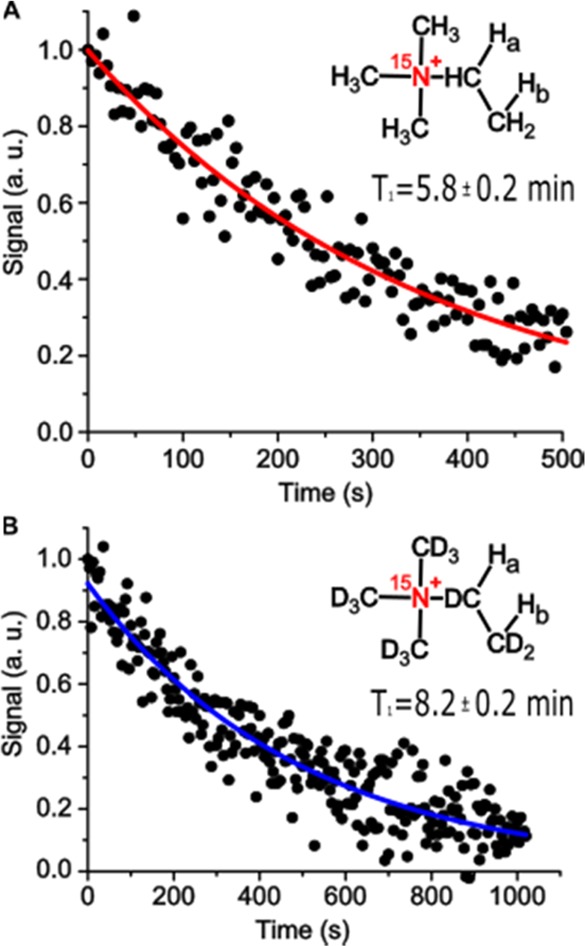

While the 15N signal increased steadily with p-H2 bubbling time for the first 30 s of reaction, after that point, the signal tended to level off until the hydrogenation reaction yield reached 100% (not shown). This behavior could be potentially explained by changes in relaxation of species adsorbed onto the catalyst particles. Importantly, the 15N hyperpolarization was found to be long-lived at 9.4 T for both the protonated and deuterated substrates, with T1 decay constants of 348 ± 10 and 494 ± 13 s, respectively (Figure 3), values that are roughly 1–2 orders of magnitude longer that the corresponding lifetimes of 1H hyperpolarization and a factor of 2 larger than that recently reported for 15N derivatives of choline.40

Figure 3.

HP 15N T1 relaxation curves measured at 9.4 T for the protonated (A) and deuterated product (B); curves are exponential fits, giving the 15N T1 values (not corrected for ∼10° tipping-angle pulses) and error margins. Note the >2-fold time axis scale difference.

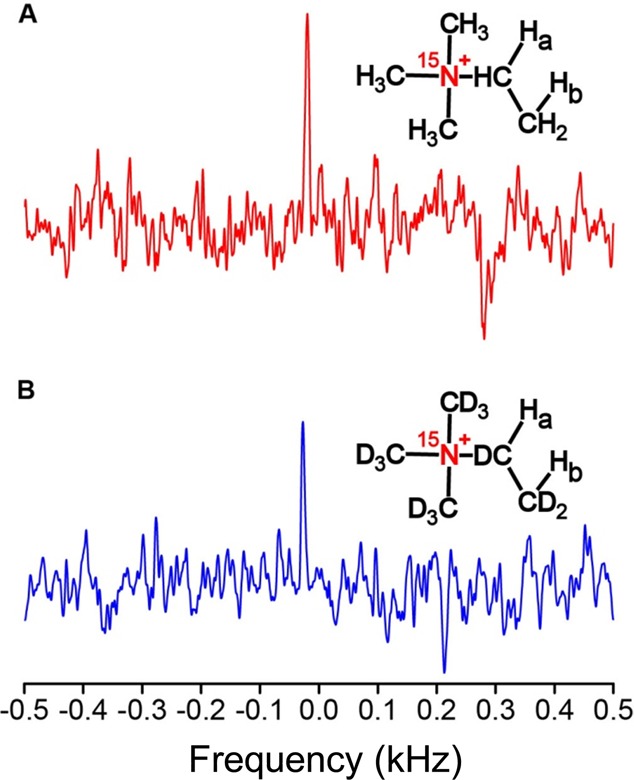

Finally, because the magnetization of HP species is not endowed by the NMR/MRI magnet, in principle, strong magnets are not required for detection. To investigate the feasibility of performing low-field NMR/MRI with 15N spins hyperpolarized by HET-PHIP, hydrogenation reaction products for both protonated and deuterated substrates were detected at 0.05 T, Figure 4. Indeed, 15N NMR resonances were successfully detected via low-field 15N NMR spectroscopy at a 210 kHz resonance frequency, with slightly greater signal observed for the protonated versus the deuterated product, which is qualitatively consistent with the high-field results. Higher polarization enhancements enabled by future experimental refinements should boost the signal to noise ratio to allow measurement of the 15N T1 at low field, where even longer hyperpolarization lifetimes would be expected,54 thereby improving storage of the HP state.

Figure 4.

Single-shot low-field (0.05 T) HP 15N NMR spectra of (A) the fully protonated product and (B) the fully deuterated product obtained via heterogeneous hydrogenation of neurine-15N bromide over a 1.0% Rh/TiO2 catalyst with 80% p-H2. Peaks of interest are at an offset of ∼(−)0.025 kHz.

Conclusions

In summary, heterogeneous Rh/TiO2 catalysts and MFC were used to achieve 15N hyperpolarization via HET-PHIP for the first time; previous transfers of spin order from p-H2 to 15N spins had only been achieved under homogeneous catalytic conditions via PHIP/MFC40 or SABRE-SHEATH.67,6815N nuclear spin polarization enhancements of ∼2 × 102 fold (at 9.4 T) were observed in aqueous solutions following hydrogenation of neurine-15N bromide with p-H2, which yielded a structural analogue of the biological molecule choline (the HP form of which has been shown promising in vivo45 because of the widespread function of choline in cellular metabolism and its significantly upregulated metabolism in cancer).69,70 Larger enhancements were observed with 1.0 versus 23.2% Rh/TiO2 as well as with higher p-H2 fractions; however, deuteration of the substrate yielded lower enhancements but a longer hyperpolarization lifetime. Indeed, very long 15N T1 values were observed at 9.4 T for both the protonated and deuterated substrates, ∼6 and >8 min, respectively. The 15N hyperpolarization via HET-PHIP also enabled observation of 15N signals at low (0.05 T) field, where even longer hyperpolarization lifetimes are expected, further demonstrating the potential for wider applicability of the approach. Moreover, these results also expand the range of molecules (including biomolecules) amenable to HET-PHIP hyperpolarization. While the molecule hyperpolarized here lacks the −OH moiety found in choline, PHIP precursors for choline hyperpolarization have been previously described.71 It should also be noted that the heterogeneous catalysts used (Rh/TiO2) are very stable and do not undergo any modifications during reaction (as was confirmed by XPS analysis; see the SI). Therefore, the absence of leaching of the active component of the catalyst material into solution, combined with the ability to use such supported metal catalysts for aqueous-phase heterogeneous hydrogenation (given their potential for facile separation), should allow not only catalyst recycling and reuse but also the preparation of pure HP substances free from the presence of the catalyst. Although the reported polarization values need to be increased further, taken together, these results open a door to the rapid and inexpensive creation of pure agents with long hyperpolarization lifetimes for various biomedical applications, including in vivo molecular MR imaging.

Acknowledgments

We thank NSF (CHE-1416432, CHE-1416268, and REU DMR-1461255), NIH (1R21EB018014, 5R00CA134749, 5R00CA134749-02S1, and 1R21EB020323), and DoD (CDMRP BRP W81XWH-12-1-0159/BC112431, PRMRP W81XWH-15-1-0271, and W81XWH-15-1-0272). I.V.K., V.I.B., and K.V.K. thank RFBR (17-54-33037 and 16-03-00407-a), MK-4498.2016.3, and FASO Russia Project # 0333-2016-0001 for basic funding. B.M.G. and A.M.C. acknowledge the SIUC MTC and NIH 1F32EB021840. L.M.K. thanks SB RAS Integrated Program of Fundamental Scientific Research No. II.2 (No. 0303-2015-0010) for catalyst preparation. The BIC team thanks RSCF (Grant #14-23- 00146).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b05912.

Experimental procedures, synthesis of protonated and deuterated substrate molecules, catalyst synthesis, catalyst characterization (before and after hydrogenation reaction), and additional figures (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Green R. A.; Adams R. W.; Duckett S. B.; Mewis R. E.; Williamson D. C.; Green G. G. R. The Theory and Practice of Hyperpolarization in Magnetic Resonance Using Parahydrogen. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2012, 67, 1–48. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou P.; Goodson B. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques for Biomedicine. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3156–3166. 10.1002/chem.201405253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R. Sensitivity Enhancement Utilizing Parahydrogen. Encycl. Magn. Reson. 2007, 9, 4365–4384. 10.1002/9780470034590.emrstm0489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barskiy D. A.; Coffey A. M.; Nikolaou P.; Mikhaylov D. M.; Goodson B. M.; Branca R. T.; Lu G. J.; Shapiro M. G.; Telkki V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; et al. NMR Hyperpolarization Techniques of Gases. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 725–751. 10.1002/chem.201603884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptyug I. V. Spin Hyperpolarization in NMR to Address Enzymatic Processes in Vivo. Mendeleev Commun. 2013, 23, 299–312. 10.1016/j.mencom.2013.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson B. M. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Laser-Polarized Noble Gases in Molecules, Materials, and Organisms. J. Magn. Reson. 2002, 155, 157–216. 10.1006/jmre.2001.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle K. M. Imaging Metabolism with Hyperpolarized 13C-Labeled Cell Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6418–6427. 10.1021/jacs.5b03300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder L. Xenon for NMR Biosensing - Inert but Alert. Phys. Medica 2013, 29, 3–16. 10.1016/j.ejmp.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen J. H.; Fridlund B.; Gram A.; Hansson G.; Hansson L.; Lerche M. H.; Servin R.; Thaning M.; Golman K. Increase in Signal-to-Noise Ratio of > 10,000 Times in Liquid-State NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 10158–10163. 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly T.; Debelouchina G. T.; Bajaj V. S.; Hu K.-N.; Joo C.-G.; Mak-Jurkauskas M. L.; Sirigiri J. R.; van der Wel P. C. A.; Herzfeld J.; Temkin R. J.; et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization at High Magnetic Fields. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 052211. 10.1063/1.2833582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. J.; Kurhanewicz J.; Vigneron D. B.; Larson P. E. Z.; Harzstark A. L.; Ferrone M.; van Criekinge M.; Chang J. W.; Park I.; et al. Metabolic Imaging of Patients with Prostate Cancer Using Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 198ra108. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshari K. R.; Wilson D. M. Chemistry and Biochemistry of 13C Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance Using Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1627–1659. 10.1039/C3CS60124B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurhanewicz J.; Vigneron D. B.; Brindle K.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Comment A.; Cunningham C. H.; Deberardinis R. J.; Green G. G.; Leach M. O.; Rajan S. S.; et al. Analysis of Cancer Metabolism by Imaging Hyperpolarized Nuclei: Prospects for Translation to Clinical Research. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 81–97. 10.1593/neo.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptyug I. V.; Kovtunov K. V.; Burt S. R.; Anwar M. S.; Hilty C.; Han S. I.; Pines A.; Sagdeev R. Z. Para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5580–5586. 10.1021/ja068653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. Parahydrogen and Synthesis Allow Dramatically Enhanced Nuclear Alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5541–5542. 10.1021/ja00252a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. W.; Aguilar J. A.; Atkinson K. D.; Cowley M. J.; Elliott P. I. P.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G. R.; Khazal I. G.; López-Serrano J.; Williamson D. C. Reversible Interactions with Para-Hydrogen Enhance NMR Sensitivity by Polarization Transfer. Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. 10.1126/science.1168877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. Transformation of Symmetrization Order to Nuclear-Spin Magnetization by Chemical Reaction and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenschmid T. C.; Kirss R. U.; Deutsch P. P.; Hommeltoft S. I.; Eisenberg R.; Bargon J.; Lawler R. G.; Balch A. L. Para Hydrogen Induced Polarization in Hydrogenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 8089–8091. 10.1021/ja00260a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y. Parahydrogen Induced Polarization of 1-13C-Phospholactate-d2 for Biomedical Imaging with > 30,000,000-Fold NMR Signal Enhancement in Water. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 5601–5605. 10.1021/ac500952z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias N. M.; Chan H. R.; Sailasuta N.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P. Real-Time Molecular Imaging of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolism in Vivo by Hyperpolarized 1-13C Diethyl Succinate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 934–943. 10.1021/ja2040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Pham W.; Chekmenev E. Y. Dephosphorylation and Biodistribution of 1-13C-Phospholactate in Vivo. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2014, 57, 517–524. 10.1002/jlcr.3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y. PASADENA Hyperpolarized 13C Phospholactate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3957–3960. 10.1021/ja210639c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Truong M. L.; Wilkens K.; Pham W.; Chekmenev E. Y. Open-Source Automated Parahydrogen Hyperpolarizer for Molecular Imaging Using 13C Metabolic Contrast Agents. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 8279–8288. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövener J.-B.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Harris K. C.; Perman W. H.; Tran T. T.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P. Quality Assurance of PASADENA Hyperpolarization for 13C Biomolecules. MAGMA 2009, 22, 123–134. 10.1007/s10334-008-0154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Reynolds W. F.; Wagner S.; Zacharias N.; Chan H. R.; Bunger R.; Ross B. D. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization (PHIP) Hyperpolarized MR Receptor Imaging in Vivo: A Pilot Study of 13C Imaging of Atheroma in Mice. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 1023–1028. 10.1002/nbm.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R.; Zhao E. W.; Cheng W.; Neal L. M.; Zheng H.; Quiñones R. E.; Hagelin-Weaver H. E.; Bowers C. R. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization by Pairwise Replacement Catalysis on Pt and Ir Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1938–1946. 10.1021/ja511476n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Salnikov O. G.; Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; Kovtunova L. M.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V.; Chekmenev E. Y. Toward Production of Pure 13C Hyperpolarized Metabolites Using Heterogeneous Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization of Ethyl [1-13C]Acetate. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 69728–69732. 10.1039/C6RA15808K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koptyug I. V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Kovtunov K. V. New Perspectives for Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Liquid Phase Heterogeneous Hydrogenation: An Aqueous Phase and ALTADENA Study. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 3086–3088. 10.1002/cphc.201000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Skovpin I. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Koptyug I. V. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Heterogeneous Catalytic Processes. Top. Curr. Chem. 2012, 338, 123–180. 10.1007/128_2012_371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloggler S.; Grunfeld A. M.; Ertas Y. N.; McCormick J.; Wagner S.; Schleker P. P. M.; Bouchard L. S. A Nanoparticle Catalyst for Heterogeneous Phase Para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization in Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2452–2456. 10.1002/anie.201409027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Jóhannesson H. Conversion of a Proton Pair Para Order into C-13 Polarization by Rf Irradiation, for Use in MRI. C. R. Phys. 2005, 6, 575–581. 10.1016/j.crhy.2005.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui S.; Kadlecek S.; Pourfathi M.; Xin Y.; Mannherz W.; Hamedani H.; Drachman N.; Ruppert K.; Clapp J.; Rizi R. The Use of Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 Magnetic Resonance for Molecular Imaging. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 10.1016/j.addr.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlecek S.; Emami K.; Ishii M.; Rizi R. Optimal Transfer of Spin-Order between a Singlet Nuclear Pair and a Heteronucleus. J. Magn. Reson. 2010, 205, 9–13. 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake M.; Natterer J.; Bargon J. Efficient NMR Pulse Sequences to Transfer the Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization to Hetero Nuclei. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8688–8691. 10.1021/ja960067f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bär S.; Lange T.; Leibfritz D.; Hennig J.; von Elverfeldt D.; Hövener J. On the Spin Order Transfer from Parahydrogen to Another Nucleus. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 225, 25–35. 10.1016/j.jmr.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C.; Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Waddell K. W. Efficient Transformation of Parahydrogen Spin Order into Heteronuclear Magnetization. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 1219–1224. 10.1021/jp3089462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jóhannesson H.; Axelsson O.; Karlsson M. Transfer of Para-Hydrogen Spin Order into Polarization by Diabatic Field Cycling. C. R. Phys. 2004, 5, 315–324. 10.1016/j.crhy.2004.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reineri F.; Boi T.; Aime S. Parahydrogen Induced Polarization of 13C Carboxylate Resonance in Acetate and Pyruvate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5858. 10.1038/ncomms6858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Shchepin R. V.; Salnikov O. G.; Prosvirin I. P.; Bukhtiyarov A. V.; Kovtunova L. M.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V.; Chekmenev E. Y. Production of Pure Aqueous 13C-Hyperpolarized Acetate by Heterogeneous Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16446–16449. 10.1002/chem.201603974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineri F.; Viale A.; Ellena S.; Alberti D.; Boi T.; Giovenzana G. B.; Gobetto R.; Premkumar S. S. D.; Aime S. 15N Magnetic Resonance Hyperpolarization via the Reaction of Parahydrogen with 15N-Propargylcholine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11146–11152. 10.1021/ja209884h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Coffey A. M.; Theis T.; Shi F.; Warren W. S.; Goodson B. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. 15N Hyperpolarization of Imidazole-15N2 for Magnetic Resonance pH Sensing via SABRE-SHEATH. ACS Sensors 2016, 1, 640–644. 10.1021/acssensors.6b00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Lumata L.; Chen W.; Zhang S.; Kovacs Z.; Sherry A. D.; Khemtong C. Hyperpolarized 15N-Pyridine Derivatives as pH-Sensitive MRI Agents. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9104. 10.1038/srep09104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka H.; Hirano M.; Imakura Y.; Takakusagi Y.; Ichikawa K.; Sando S. Design of a 15N Molecular Unit to Achieve Long Retention of Hyperpolarized Spin State. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40104. 10.1038/srep40104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka H.; Hata R.; Doura T.; Nishihara T.; Kumagai K.; Akakabe M.; Tsuda M.; Ichikawa K.; Sando S. A Platform for Designing Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance Chemical Probes. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2411. 10.1038/ncomms3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slichter C. P. The Discovery and Demonstration of Dynamic Nuclear Polarization—a Personal and Historical Account. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 5741–5751. 10.1039/c003286g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Kreis F.; Wright A. J.; Hesketh R. L.; Levitt M. H.; Brindle K. M. Dynamic 1H Imaging of Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Lactate In Vivo Using a Reverse INEPT Experiment. Magn. Reson. Med. 2017, 10.1002/mrm.26725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekmenev E. Y.; Norton V. A.; Weitekamp D. P.; Bhattacharya P. Hyperpolarized 1H NMR Employing Low Nucleus for Spin Polarization Storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3164–3165. 10.1021/ja809634u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R.; Comment A.; Vasos P. R.; Jannin S.; Gruetter R.; Bodenhausen G.; Hall H. H.; Kirik D.; Denisov V. P. Proton NMR of 15N-Choline Metabolites Enhanced by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16014–16015. 10.1021/ja9021304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeilsticker J. A.; Ollerenshaw J. E.; Norton V. A.; Weitekamp D. P. A Selective 15N-to-1H Polarization Transfer Sequence for More Sensitive Detection of 15N-Choline. J. Magn. Reson. 2010, 205, 125–129. 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton V. A.; Weitekamp D. P. Communication: Partial Polarization Transfer for Single-Scan Spectroscopy and Imaging. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 135, 141107. 10.1063/1.3652965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong M. L.; Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Waddell K. W.; Chekmenev E. Y. Sub-Second Proton Imaging of 13C Hyperpolarized Contrast Agents in Water. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2014, 9, 333–341. 10.1002/cmmi.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkovsky M.; Comment A.; Gruetter R. In Vivo Detection of Brain Krebs Cycle Intermediate by Hyperpolarized Magnetic Resonance. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 2108–2113. 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis T.; Ortiz G. X.; Logan A. W. J.; Claytor K. E.; Feng Y.; Huhn W. P.; Blum V.; Malcolmson S. J.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Wang Q.; et al. Direct and Cost-Efficient Hyperpolarization of Long-Lived Nuclear Spin States on Universal 15N2-Diazirine Molecular Tags. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501438–e1501438. 10.1126/sciadv.1501438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colell J. F. P.; Logan A. W. J.; Zhou Z.; Shchepin R. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Ortiz G. X.; Wang Q.; Malcolmson S. J.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Warren W. S.; et al. Generalizing, Extending, and Maximizing Nitrogen-15 Hyperpolarization Induced by Parahydrogen in Reversible Exchange. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 6626–6634. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barskiy D. A.; Salnikov O. G.; Romanov A. S.; Feldman M. A.; Coffey A. M.; Kovtunov K. V.; Koptyug I. V.; Chekmenev E. Y. NMR Spin-Lock Induced Crossing (SLIC) Dispersion and Long-Lived Spin States of Gaseous Propane at Low Magnetic Field (0.05 T). J. Magn. Reson. 2017, 276, 78–85. 10.1016/j.jmr.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pravica M. G.; Weitekamp D. P. Net NMR Alignment by Adiabatic Transport of Parahydrogen Addition Products to High Magnetic Field. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 145, 255–258. 10.1016/0009-2614(88)80002-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golman K.; Axelsson O.; Johannesson H.; Mansson S.; Olofsson C.; Petersson J. S. Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization in Imaging: Subsecond 13C Angiography. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001, 46, 1–5. 10.1002/mrm.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallari E.; Carrera C.; Boi T.; Aime S.; Reineri F. Effects of Magnetic Field Cycle on the Polarization Transfer from Parahydrogen to Heteronuclei through Long-Range J-Couplings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 10035–10041. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b06222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Coffey A. M.; Esteve I. V. M; Chekmenev E. Y. Efficient Synthesis of Molecular Precursors for Para-Hydrogen-Induced Polarization of Ethyl Acetate-1-13C and Beyond. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6071–6074. 10.1002/anie.201600521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Coffey A. M.; Truong M. L.; Salnikov O. G.; Khudorozhkov A. K.; Inozemtseva E. A.; Prosvirin I. P.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Waddell K. W.; et al. High-Resolution 3D Proton MRI of Hyperpolarized Gas Enabled by Parahydrogen and Rh/TiO2 Heterogeneous Catalyst. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11636–11639. 10.1002/chem.201403604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Salnikov O. G.; Burueva D. B.; Khudorozhkov A. K.; Bukhtiyarov A. V.; Prosvirin I. P.; Gerasimov E. Y.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V. Strong Metal-Support Interactions for Palladium Supported on TiO2 Catalysts in the Heterogeneous Hydrogenation with Parahydrogen. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2581–2584. 10.1002/cctc.201500618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burueva D. B.; Salnikov O. G.; Kovtunov K. V.; Romanov A. S.; Kovtunova L. M.; Khudorozhkov A. K.; Bukhtiyarov A. V.; Prosvirin I. P.; Bukhtiyarov V. I.; Koptyug I. V. Hydrogenation of Unsaturated Six-Membered Cyclic Hydrocarbons Studied by the Parahydrogen-Induced Polarization Technique. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 13541–13548. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b03267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chekmenev E. Y.; Hövener J.-B.; Norton V. A.; Harris K.; Batchelder L. S.; Bhattacharya P.; Ross B. D.; Weitekamp D. P. PASADENA Hyperpolarization of Succinic Acid for MRI and NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4212–4213. 10.1021/ja7101218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Perman W. H.; Harris K. C.; Lin A. P.; Norton V. A.; Tan C. T.; Ross B. D.; Weitekamp D. P. Towards Hyperpolarized 13C-Succinate Imaging of Brain Cancer. J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 186, 150–155. 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche-Arnon H.; Lerche M. H.; Karlsson M.; Lenkinski R. E.; Katz-Brull R. Deuteration of a Molecular Probe for DNP Hyperpolarization - A New Approach and Validation for Choline Chloride. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2011, 6, 499–506. 10.1002/cmmi.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Truong M. L.; Theis T.; Coffey A. M.; Shi F.; Waddell K. W.; Warren W. S.; Goodson B. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. Hyperpolarization of “Neat” Liquids by NMR Signal Amplification by Reversible Exchange. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 1961–1967. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barskiy D. A.; Shchepin R. V.; Coffey A. M.; Theis T.; Warren W. S.; Goodson B. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. Over 20% 15N Hyperpolarization in Under One Minute for Metronidazole, an Antibiotic and Hypoxia Probe. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8080–8083. 10.1021/jacs.6b04784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis T.; Truong M. L.; Coffey A. M.; Shchepin R. V.; Waddell K. W.; Shi F.; Goodson B. M.; Warren W. S.; Chekmenev E. Y. Microtesla SABRE Enables 10% Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Spin Polarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1404–1407. 10.1021/ja512242d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma U.; Baek H. M.; Su M. Y.; Jagannathan N. R. In Vivo 1H MRS in the Assessment of the Therapeutic Response of Breast Cancer Patients. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 700–711. 10.1002/nbm.1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrius M. D.; Pijnappel R. M.; Jansen-van der Weide M. C.; Jansen L.; Kappert P.; Oudkerk M.; Sijens P. E. Determination of Choline Concentration in Breast Lesions: Quantitative Multivoxel Proton MR Spectroscopy as a Promising Noninvasive Assessment Tool to Exclude Benign Lesions. Radiology 2011, 259, 695–703. 10.1148/radiol.11101855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchepin R. V.; Chekmenev E. Y. Synthetic Approach for Unsaturated Precursors for Parahydrogen Induced Polarization of Choline and Its Analogs. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2013, 56, 655–662. 10.1002/jlcr.3082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.