Abstract

Polyploidy is an important factor shaping the geographic range of a species. Clintonia udensis (Clintonia) is a primary perennial herb widely distributed in China with two karyotypic characteristics—diploid and tetraploid and thereby used to understand the ploidy and distribution. This study unraveled the patterns of genetic variation and spatiotemporal history among the cytotypes of C. udensis using simple sequence repeat or microsatellites. The results showed that the diploids and tetraploids showed the medium level of genetic differentiation; tetraploid was slightly lower than diploid in genetic diversity; recurrent polyploidization seems to have opened new possibilities for the local genotype; the spatiotemporal history of C. udensis allows tracing the interplay of polyploidy evolution; isolated and different ecological surroundings could act as evolutionary capacitors, preserve distinct karyological, and genetic diversity. The approaches of integrating genetic differentiation and spatiotemporal history of diploidy and tetraploidy of Clintonia udens would possibly provide a powerful way to understand the ploidy and plant distribution and undertaken in similar studies in other plant species simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid.

Keywords: Clintonia udensis, genetic differentiation, karyotypic characteristics, simple sequence repeat or microsatellites

1. INTRODUCTION

Polyploidy is considered important to shape the geographic range of a species. For instance, Centaurea maculosa (Asteraceae) of diploid is even more pronounced in the introduced North American range than tetraploid cytotypes (Treier, Broennimann, Normand, Guisan, & Schaffner, 2009); the distribution of diploid and tetraploid races of Brachypodium distachyon (Poaceae) is geographically structured with an aridity gradient (Manzaneda, Rey, Bastida, & Weiss‐Lehman, 2012a,b); B. distachyon (Poaceae) of tetraploids likely is coresponsible for its occurrence in more arid regions compared with the diploid cytotype (Manzaneda et al., 2012a,b). However, few studies were to understand the ploidy and plant distribution in plant species simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid.

The majority of polyploid taxa are of multiple and spatially and/or temporally recurrent origin potentially increasing the polyploid's genomic diversity: The spatiotemporal history of Knautia arvensis allows tracing the interplay of polyploid evolution and ecological divergence on serpentine, resulting in a complex evolutionary pattern (Filip et al., 2012); allopolyploid speciation in action with the origins and evolution of Senecio cambrensis (Hegarty, Abbott, & Hiscock, 2012); the early stages of polyploidy of rapid and repeated evolution in Tragopogon upon genetic diversity (Soltis, Buggs, Barbazuk, Chamala, & Chester, 2012; Soltis, Buggs, Barbazuk, Schnable, & Soltis, 2009; Soltis & Soltis, 1999); the promiscuous and the chaste of frequent allopolyploid speciation and its genomic consequences in American daisies (Weiss‐Schneeweiss et al., 2012). The geographic distance and the multilocus genetic distance between individuals were computed to evaluate spatial genetic structure of individuals using spatial autocorrelation coefficient; for example, EST‐SSRs were used to characterize polymorphism among 29 Chrysanthemum and Ajania spp. accessions of various ploidy levels (Wang, Qi, Gao, & Wang, 2014); genetic variation in polyploid forage grass was assessed the molecular genetic variability in the Paspalum genus (Fernand, Bianca, & Francisco, 2013); public cotton SSR libraries (17,343 markers) were curated for sequence redundancy using 90% as a similarity cut‐off (Anna, David, Jean, & Olivier, 2012); spatiotemporal history of the diploid–tetraploid complex of K. arvensis (Dipsacaceae) upon evolution on serpentine and polyploidy (Filip et al., 2012), genetic, and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids (Pamela & Douglas, 2000). Species with little genetic variability may suffer from reduced fitness and may not show the potential evolutionary necessary under the changed environment (Bodare, Tsuda, Ravikanth, Shaanker, & Lascoux, 2013; Gong, Zhan, & Wang, 2015). Genetic diversity and differentiation under different levels could be assessed to provide the understanding of the evolutionary history within species. Numbers of PCR‐based techniques including Simple Sequence Repeat or microsatellites (SSR) were used to analysis the polymorphisms of genetic diversity and spatiotemporal history: genetic analysis and molecular characterization of Chinese sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) cultivars using SSR markers (Wu, Yang, Liu, Tao, & Zhao, 2014); genetic diversity and population structure assessed by SSR marker in a large germplasm collection of grape (Francesco et al., 2013); genetic diversity, genetic structure, and demographic history of Cycas simplicipinna (Cycadaceae) assessed by SSR markers (Feng, Wang, & Gong, 2014).

Clintonia udensis (Liliaceae)Trautv. et Mey. (Clintonia) is perennial with globose or ellipsoid blackish‐blue berry widely distributed in the area of Japano‐Himalayan element from the Japanese Islands to the Himalayan Mountains in northeastern Asia at 1,600 m to 4,000 m above sea level (Kanai, 1963; Kim, Kim, & Chase, 2016; Wagner, 1973; Wang et al., 1978). The diploid of C. udensis (2n = 14 and 4n = 28) was distributed in northwest Yunnan of China and Primorskiy Kray in Russia while the tetraploid were spread Yunnan, the Himalayas, Japan, and Mount Hualongshan (Figure 1) (Li, Chang, & Yuan, 1996; Wang et al., 1978). Those areas were studied for the genetic diversity and phylogeography, indicate that the history of C. udensis involved both long‐distance migration and the tectonic events of Mountains in East Asia; and mixed‐mating—breeding system, limited gene flow, environmental stress, and historical factors may be the main factors causing geographic differentiation in the genetic structure of C. udensis (Wang, Guo, & Zhao, 2011; Wang, Li, Guo, Li, & Zhao, 2010). However, only two regions (Hunan and Shaanxi provinces) of the C. udensis range were simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid. Geographically the diploid and tetraploid are parapatric or partially was overlapping (Li & Chang, 1996; Li et al., 1996), the diploid and tetraploid of C. udensis was no corresponding morphological differentiation except that seeds of tetraploid are constantly bigger than that of diploid (Li & Chang, 1996; Li et al., 1996), the derivation from lower ploid level to higher ploidy level is an irreversible process (Huang, 1990), and the tetraploid types generally could adapt new different environment than diploid types (Huang, 1990; Li & Chang, 1996; Li et al., 1996). Thus, C. udensis was an ideal plant to understand the ploidy and distribution based on diploid and tetraploid. This study was (1) to analyze the genetic level of C. udensis in both diploid and tetraploid using the SSR markers, (2) to explain the intraspecific genetic differentiation of C. udensis in populations from the diploid and tetraploid types, (3) to describe the phylogeographic population relationships, and to explore the origin of tetaploid by recurrent polyploidization or by colonization. The approaches of integrating genetic differentiation and spatiotemporal history of diploidy and tetraploidy of Clintonia udens provide a powerful way to understand the ploidy and plant distribution and could be undertaken in similar studies in other plant species simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid.

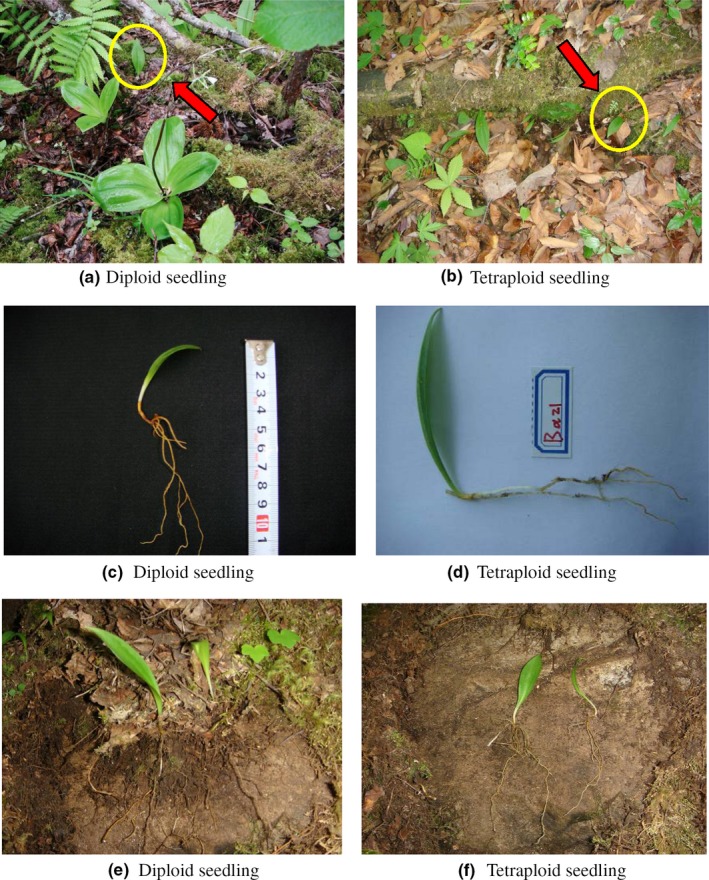

Figure 1.

(a, c, e) are seedling of Clintonia udensis (2n); (b, d, f) are seedling of C. udensis (4n). The red arrow means the seedling of (2n) in picture a and the seedling of C. udensis (4n) in picture b; picture c and d means the seeding size of C. udensis (2n and 4n), picture e and f means the root of C. udensis

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Plant material

The fresh leaves of 31–41 individuals were collected randomly in four natural populations (HLN, JHL, HLB, and MLZ) of C. udensis. Among the four populations, the karyotypic characteristics of HLN and JHL populations are diploid cytotype while HLB and MLZ are tetraploid cytotype. The HLN and HLB populations located at Hualongshan Mountains in Shaanxi Province while JHL and MLZ located at Shennongjia Mountains in Hunan province. This study was included total of 152 individuals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Location between experimental materials and environmental factors

| Population | Location | Samples | Longitude | Latitude | Altitude (m) | Isothermality (*100) | Precipitation of warmest quarter (mm) | Precipitation of coldest quarter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLB (tetraploid) | Hualongshan Shaanxi | 39 | 31.10 | 109.68 | 2,033 | 27 | 414 | 42 |

| HLN (diploid) | Hualongshan Shaanxi | 31 | 32.02 | 109.58 | 2,404 | 27 | 454 | 48 |

| JHL (diploid) | Jinhouling Hubei | 41 | 31.78 | 110.50 | 2,479 | 25 | 505 | 60 |

| MLZ (tetraploid) | Mulinzi Hubei | 41 | 30.05 | 110.33 | 2,042 | 27 | 600 | 72 |

2.2. Microsatellites amplification

The leaves were used to extracted genomic DNA followed the method of CTAB (Doyle & Doyle, 1987). The locus of polyploids is potentially higher than the diploids upon the number of alleles (Pfeiffer, Roschanski, Pannell, Korbecka, & Schnittler, 2011; Teixeira, Rodríguez‐Echeverría, & Nabais, 2014). Polymorphic 20 microsatellite loci were tested from an initial set of putative for developed of Liliaceae. Polymorphic 20 microsatellite loci were tested from an initial set of putative for developed of Liliaceae (Chung & Jack, 2003; Guo, Wang, Li, & Zhao, 2011). The targeted and polymorphism loci were amplified successfully in eleven of these 20 primers used in this study (Table 2). The data sets of SSR markers were collected by polyacrylamide gel (PAGE) silver staining. PCR that did not produce bands or that had different size were repeated.

Table 2.

The SSR primers used in the study

| Random primer pairs and annealing temperature | Random primer pairs and annealing temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ccSSR‐6 | F:CGACCAATCCTTCCTAATTCAC | ccSSR‐7 | F:CGGGAAGGGCTCGKGCAG |

| 56.2°C | R:AGAAAAGMAAGGATATGGGCTC | 56.2°C | R:GTTCGAATCCCTCTCTCTCCTTTT |

| ccSSR‐9 | F:GAGGATACACGCAGARGGARTTG | ccSSR‐12 | F:CCAAAAACTTGGAGATCCAACTAC |

| 58°C | R:CCTATTACAGAGATGGTGYGATTT | 56.2°C | R:TTCCATAGATTCGATCGTGGTTTA |

| ccSSR‐15 | F:GCTTATGACCTCCCCCTCTATGC | ccSSR‐16 | F:TACGAGTCACCCCTTTCATTC |

| 58°C | R:TGCATTACAGACGTATGATCATT | 56.2°C | R:CCTGGCCCAACCCTAGACA |

| ccSSR‐17 | F:CACACCAATCCATCCCGAACT | ccSSR‐20 | F:CCGCARATATTGGAAAAACWACAA |

| 60°C | R:GGTGCGTTCCGRGGTGTGA | 55°C | R:GCTAARCAAATWGCTTCTGCTCC |

| ccSSR‐21 | F:CCACCCCGTCTCSACTGGATCT | ccSSR‐22 | F:CCGACCTAGGATAATAAGCYCATG |

| 56.2°C | R:AQAAAATAGCTCGACGCCAGGAT | 58°C | R:GGAAGGTGCGGCTGGATC |

| ccSSR‐23 | F:AYGGRGGTGGTGAAGGGAG | ||

| 58°C | R:TCAATTCCCGTCGTTCGCC |

2.3. Data analysis

The software of GenoDive was used to calculate effective number of alleles per locus (Ae) and heterozygosity within each population (Hs) (Meirmans & Vartienderen, 2004). GenAlex 6.5 was used for further analysis of the multilocus data (Peakall & Smouse, 2012), including number of alleles, genetic diversity, Shannon's information index, finescale genetic structure (Kloda, Dean, Maddren, MacDonald, & Mayes, 2008; Obbard, Harris, & Pannell, 2006; Peakall & Smouse, 2006; Sampson & Byrne, 2012; Teixeira et al., 2014). PhiPT was used to determine the genetic differentiation between populations, and a Mantel test was performed for genetic and geographic distances (Assoumane, Zoubeirou, Rodier‐Goud, & Favreau, 2012; Mantel, 1967). The genetic similarity between samples was explored for principal component analysis (PCA) using PolySat, an R package for polyploid microsatellite analysis in ecological genetics (Clark & Jasieniuk, 2011). The STRUCTURE software version 2.2 was used to assess the population genetic structure following a model‐based Bayesian assignment that allows mixed ancestry of individuals (admixture model). (Evanno & Regnaut, 2005; Hubisz, Falush, Stephens, & Pritchard, 2009; Pritchard, Stephens, & Donnelly, 2000), and the genetic clusters (K) of individuals were assumed in Hardy–Weinberg and linkage equilibria were given number from K = 1 to K = 4 to investigate under the correlated allele frequencies model by running 100,000 iterations. A Neighbor‐joining (NJ) tree was performed the genetic relationships among populations ((Nei, Tajima, & Tateno, 1983; Rambaut, 2014).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Genetic diversity

All amplified loci were highly polymorphic and displayed up to 4.15 alleles per sample from the 12 microsatellite loci of total of 50 alleles, and the number of private alleles and different alleles of diploid were generally higher than tetraploid within each population (An) (Wilcoxon test, p = .01). The average number of effective alleles per locus and high values of heterozygosity was similar in all populations. Significantly higher values were also found in all populations for the Shannon's information index (I) (Table 3, Wilcoxon tests, p = .035). Two cytotyped were significant differences found in these diversity estimators (Wilcoxon test, p = .046) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diversity of the studied populations of Clinton udensis obtained from the analysis of microsatellite loci

| Population | N | An | Ae′ | PA | Hs | I | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JHL (diploid) | 39 | 0.719 | 1.291 | 12 | 0.156 | 0.222 | 0.085 |

| HLN (diploid) | 31 | 0.438 | 1.191 | 7 | 0.101 | 0.143 | 0.131 |

| Total diploid | 70 | 0.578 | 1.241 | 19 | 0.129 | 0.182 | 0.108 |

| HLB (tetraploid) | 41 | 0.313 | 1.112 | 4 | 0.065 | 0.094 | 0.058 |

| MLZ (tetraploid) | 41 | 0.531 | 1.216 | 8 | 0.114 | 0.162 | 0.098 |

| Total tetraploid | 82 | 0.422 | 1.164 | 12 | 0.090 | 0.128 | 0.078 |

| Total species | 152 | 0.500 | 1.202 | 0.109 | 0.155 | 0.193 |

N, number of individuals; An, number of alleles in each population; Ae′, average number of effective alleles per locus; PA, number of private alleles per population; Hs, heterozygosity within populations; I, Shannon's Information Index; H, genetic diversity.

Twenty‐nine alleles of the observed 50 alleles were shared by all populations while the rest were exclusively found in diploid or tetraploid population. About 38% of private alleles were found only in diploid populations while 24% were found exclusively in the tetraploid populations, and JHL was the highest while HLB was the lowest private alleles. And the locus 4 was the locus with the highest number of private alleles.

3.2. Population differentiation and genetic structure

PhiPT distances were ranged between 0.673 (HLN/HLB) and 0.813 (JHL/MLZ) and were statistically significant between all studied populations (Table 4). It indicated that the genetic diversity among populations were occurred with 77% while within populations were contributed 23% (Table 5). Whether diploid (80%, p = .001) or tetraploid (69%, p = .001) populations, the genetic variability was also both mainly found among populations.

Table 4.

Pairwise PhiPT genetic distance between the studied populations

| Population | JHL (diploid) | HLN (diploid) | HLB (tetraploid) | MLZ (tetraploid) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JHL (diploid) | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| HLN (diploid) | 0.801 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| HLB (tetraploid) | 0.767 | 0.673 | 0 | 0.001 |

| MLZ (tetraploid) | 0.813 | 0.768 | 0.693 | 0 |

PhiPT values are shown below diagonal. Probability based on 1,000 permutations was shown above diagonal.

Table 5.

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) showing the partitioning of genetic variation within and between populations of Clinton udensis

| Source of variation | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among diploid populations | 1 | 206.623 | 206.623 | 5.939 | 80 | .001 |

| Within diploid populations | 68 | 100.491 | 1.478 | 1.478 | 20 | |

| Among tetraploid populations | 1 | 125.659 | 125.659 | 3.032 | 69 | .001 |

| Within tetraploid populations | 80 | 107.463 | 1.343 | 1.343 | 31 | |

| Among populations | 3 | 524.322 | 174.774 | 4.580 | 77 | .001 |

| Within populations | 148 | 207.955 | 1.405 | 1.405 | 23 |

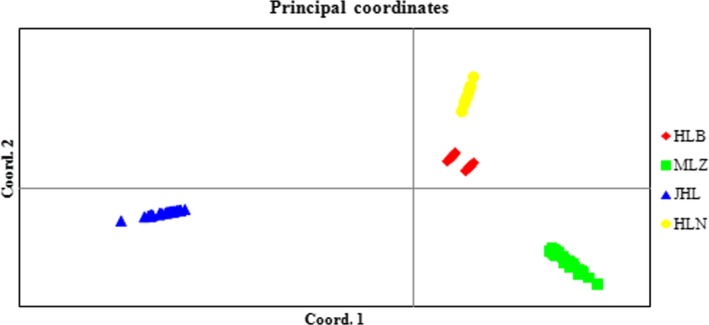

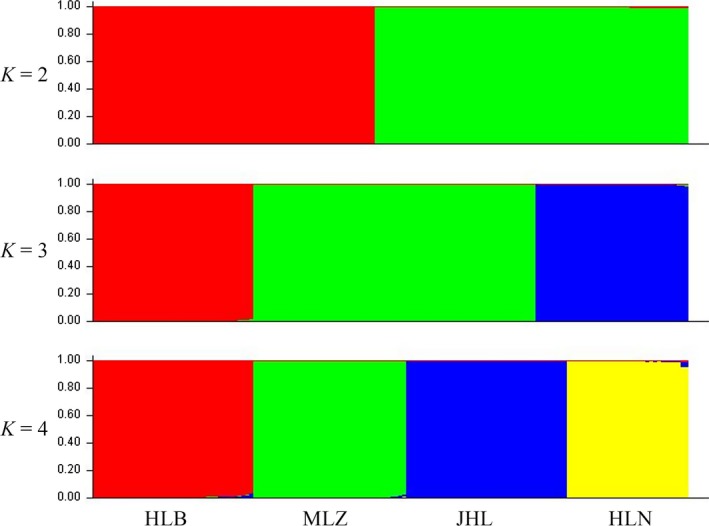

The samples were separated into three groups by the PCA, with some overlap (Figure 2). The correlation of genetic and geographic distances was significant revealed under the Mantel test based on Euclidean distances (R 2 = 0.024, p = .001). Bayesian analysis showed populations of diploid JHL, and HLN were grouped into one cluster while populations of tetraploid MLZ and HLB were grouped into the other cluster that with the value of K = 2, which was dominant in each of the two cytotype; the population of diploid HLN and population of tetraploid HLB solely gathered a cluster, respectively, with the value of K = 3; four populations were, respectively, gathered different cluster and were easily distinguished with the value of K = 4 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis (PCoA) of the 152 individuals based on microsatellite loci. HLN and JHL: diploid population of Clintonia udensis; HLB and MLZ: tetraploid population of C. udensis. The abbreviation of HLN means Hualongshan, JHL means Jinhouling, HLB means Hualongshan, and MLZ means Mulinzi

Figure 3.

Means of assignment coefficients to each group (K) per population. HLNand JHL: diploid population of Clintonia udensis; HLB and MLZ: tetraploid population of C. udensis. The abbreviation of HLN means Hualongshan, JHL means Jinhouling, HLB means Hualongshan, and MLZ means Mulinzi

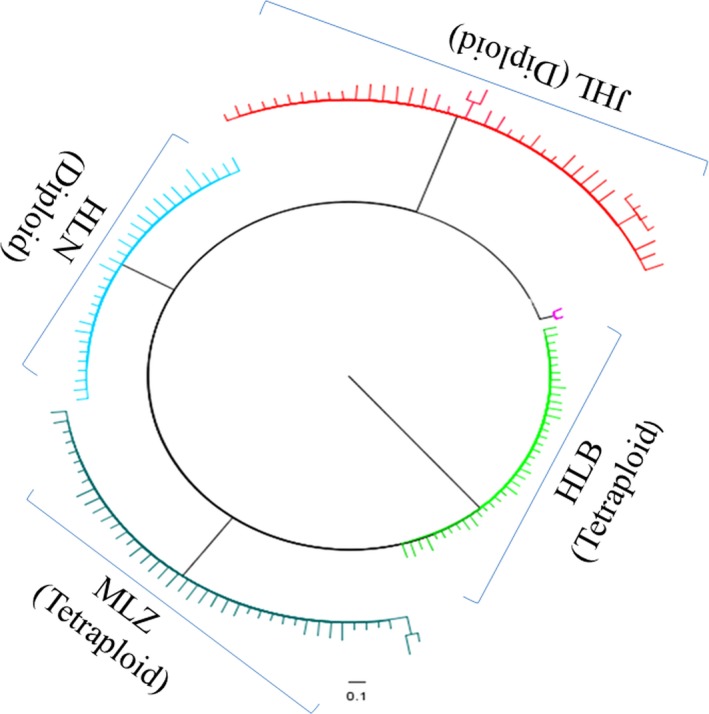

The dendrogram (Figure 4) obtained with the Neighbor‐joining clustering method showed that the studied populations were separated into three clades with high bootstrap values. It is the same as STRUCTURE and PCA.

Figure 4.

Dendrogram of Clintonia udensis samples based on genetic distance. HLN and JHL: diploid population of C. udensis; HLB and MLZ: tetraploid population of C. udensis. The abbreviation of HLN means Hualongshan, JHL means Jinhouling, HLB means Hualongshan, and MLZ means Mulinzi

4. DISCUSSION

It is hypothesized that polyploids were contributed to greater genetic and biochemical diversity, and thus, polyploids are expected to have larger geographic ranges and/or occur in more habitats than diploids. The analysis of four populations of C. udensis using 11 polymorphic SSR revealed clear separation between the diploid and tetraploid populations and moderate values of genetic diversity. The variability was accounted for 67% in diploid and tetraploid while variation was accounted for 77% of the total genetic diversity.

The genetic differentiation of diploid and tetraploid populations was probably contributed to the geographic barrier. PCA C. udensis populations were more diverse in diploid than in tetraploid in terms of higher genetic diversity and isolation by distance also indicated in the Mental test, the colonization history of C. udensis was possibly due to the medium genetic diversity in tetraploid upon C. udensis originated in East Asian and then through the Beringia bridge spread to North American, similar studies were reported in alfalfa or other herbs (Li & Chang, 1996; Qiang et al., 2015). Our study indicates bottleneck effect was contributed to possible loss of genetic diversity during migration and environmental filters arised in North American or genetic drift, isolated evolution of the migrant genotypes was probably lead to the current genetic differentiation between diploid and tetraploid.

Diploid ancestors were probably arise during the middle of the Tertiary period to be restricted to refugia by expanding forest vegetation (Li & Chang, 1996; Wang et al., 2010). Mechanisms of allopatric differentiation taken place upon spatial isolation and population size fluctuations were leaded to the genetic differentiation observed in the diploid populations, illustrated by the significance of refugia for preserving rare and distinct genetic diversity of diploid within C. udensis. Two factors could also be contributed to the medium genetic diversity of C. udensis tetraploid: Local and glacial survival might be leaded to tetraploid with a medium genetically diverse; the lack of genetic bottlenecks and the maintenance of large effective population sizes was contributed to genetic diversity of tetraploid population during postglacial migration.

Marked diversity of polyploidy complexes showed frequent component of polyploid evolution for recurrent origin exhibited striking differences in morphology, ecology, or genetic profiles formed polyploid lineages (Brochmann, Soltis, & Soltis, 1992; Segraves, Thompson, Soltis, & Soltis, 1999; Soltis & Soltis, 1999; Soltis, Soltis, Pires, & Kovarik, 2004; Soltis, Soltis, & Tate, 2003). Diploids and tetraploids of C. udensis observed in China for its mosaic pattern while the contact zones found no populations with mixed ploidal levels respected to the origin of the tetraploids, either be recent autopolyploidization event or the secondary contact of formerly allopatric populations (Schmickl, Paule, Klein, Marhold, & Koch, 2012). Moreover, the higher number of private alleles of diploid population might reflect the existence of glacial refugia or higher historical or contemporary gene flow contribute to diploid and tetraploid of population (Li & Chang, 1996).

The tetraploids of C. udensis were formed independently by autopolyploidization (Li & Chang, 1996; Li et al., 1996). The local diploid and tetraploids suggested the basis of phenotypic similarities and habitat preferences (Kaplan, 1998). The strong introgression of the tetraploid genotype into the diploids ruled out was due to the virtual lack of triploid hybrids (Kolář, Fér, Štech, Trávníček, & Dušková, 2012; Kolář, Štech, Trávníček, Rauchová, & Urfus, 2009). In addition, no indication of across‐ploidy genetic admixture was in the other contact zone between the tetraploids and diploids, two individuals of the tetraploid population HLB single gathered a cluster indicated the complex mechanism of tetraploid of C. udensis.

In summary, polyploidy is contributed to shape the geographic range of a species. Two regions (Hunan and Shaanxi provinces) distributed the diploid (HLN, JHL) and tetraploid (HLB and MLZ) of C. udensis (2n = 14 and 4n = 28) were arised from the isolated and different ecological surroundings, which could be evolutionary capacitors to preserved distinct karyological, and diploid–tetraploid complex that exhibits an intriguing pattern of eco‐geographic differentiation. However, polyploidy is a significant and complex mode of species formation in plants, therefore, firstly, solely depend on the genome DNA of SSR markers of plant distribution and polyploidy was limited and Reduced‐Representation Genome Sequencing should be used to the polyploidy genome analysis of phylogeography to confirm the relationship of the ploidy and plant distribution in plant species simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid in the future; secondly, only four populations simultaneously contained the diploid and tetraploid are difficult to explain the factors involved in the origin and establishment of polyploids in nature, and the rest samples of other regions of YLXS (C. udensis, 4n = 28) and DGK, HSK, LW, MLG, GBS, LTDZ, HHL, TBS, FP, KZQ, EMS, JYH (C. udensis, 2n = 14) should be collected and analyzed in the future study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

JH, SNW, and YLW designed the study; JL and ZLF performed data management; JH and SNW analyzed the data and interpreted the results; JH, SNW, and YLW wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Bai GQ (Northwest University) for his assistance with field sampling and thank Huang ZH provided the Figure 1. This research was supported by the Shanxi Natural Science Foundation (2015011069).

He J, Wang S, Li J, Fan Z, Liu X, Wang Y. Genetic differentiation and spatiotemporal history of diploidy and tetraploidy of Clintonia udensis . Ecol Evol. 2017;7:10243–10251. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3510

REFERENCES

- Anna, B. , David, D. F. , Jean, F. R. , & Olivier, G. (2012). A high density consensus genetic map of tetraploid cotton that integrates multiple component maps through molecular marker redundancy check. PLoS ONE, 7, e45739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assoumane, A. , Zoubeirou, A. M. , Rodier‐Goud, M. , & Favreau, B. (2012). Highlighting the occurrence of tetraploidy in Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. and genetic variation patterns in its natural range revealed by DNA microsatellite markers. Tree Genetic Genomes, 9, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bodare, S. , Tsuda, Y. , Ravikanth, G. , Shaanker, R. U. , & Lascoux, M. (2013). Genetic structure and demographic history of the endangered tree species Dysoxylum malabaricum (Meliaceae) in Western Ghats, India: Implications for conservation in a biodiversity hotspot. Ecology and Evolution, 3, 3233–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochmann, C. , Soltis, S. P. , & Soltis, D. E. (1992). Multiple origins of the octoploid Scandinavian endemic Draba cacuminum: Electrophoretic and morphological evidence. Nordic Botany, 12, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S. M. , & Jack, E. S. (2003). The development and evaluation of consensus chloroplast primer pairs that possess highly variable sequence regions in a diverse array of plant taxa. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 107, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L. V. , & Jasieniuk, M. (2011). POLYSAT: An R package for polyploidy microsatellite analysis. Molecular Ecology and Resource, 11, 562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J. J. , & Doyle, J. L. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small qualities of fresh leaf material. Photochemistry Bullet, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Evanno, G. , & Regnaut, S. (2005). Decting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Molecular Ecology, 14, 2611–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X. Y. , Wang, Y. H. , & Gong, X. (2014). Genetic diversity, genetic structure and demographic history of Cycas simplicipinna (Cycadaceae) assessed by DNA sequences and SSR markers. BMC Plant Biology, 14, 187–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernand, W. C. , Bianca, B. Z. , & Francisco, H. D. (2013). Genetic variation in polyploid forage grass: Assessing the molecular genetic variability in the Paspalum genus. BMC Genetics, 14, 50–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip, K. , Tomaš, F. , Milan, S. , Pavel, T. , Eva, D. , Peter, S. , & Jan, S. (2012). Bringing together evolution on serpentine and polyploidy: Spatiotemporal history of the diploid–tetraploid complex of Knautia arvensis (Dipsacaceae). PLoS ONE, 7, e39988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesco, E. , Silvia, L. , Lukasz, G. , Valentina, C. , Marco, S. , & Michela, T. (2013). Genetic diversity and population structure assessed by SSR and SNP markers in a large germplasm collection of grape. BMC Plant Biology, 13, 39–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y. Q. , Zhan, N. , & Wang, G. (2015). The historical demography and genetic variation of the endangered Cycas multipinnata (Cycadaceae) in the res river region examined by Chloroplast DNA sequences and microsatellite markers. PLoS ONE, 10, e0117719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. , Wang, Y. L. , Li, S. F. , & Zhao, G. F. (2011). The genetic diversity and the genetic differentiation of Clintonia undensis using cpSSR markers. Sciencepaper Online Biochemical systematics and ecology, 39, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, M. J. , Abbott, R. J. , & Hiscock, S. J. (2012). Allopolyploid speciation in action: The origins and evolution of Senecio cambrensis In Soltis P. S., & Soltis D. E. (Eds.), Polyploidy and genome evolution (pp. 245–270). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D. Y. (1990). Plant cytotaxonomy. Beijing: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hubisz, M. J. , Falush, D. , Stephens, M. , & Pritchard, J. K. (2009). Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Molecular Resource, 9, 1322–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai, H. (1963). Phytogeographical observations on the JapanoHimalayan elements. Journal of Faculty of Science. University of Tokyo, Series III, 8, 305–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Z. (1998). Relict serpentine populations of Knautia arvensis s. l. (Dipsacaceae) in the Czech Republic and an adjacent area of Germany. Preslia, 70, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. C. , Kim, J. S. , & Chase, M. W. (2016). Molecular phylogenetic relationships of Melanthiaceae (Liliales) based on plastid DNA sequences. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 181, 567–584. [Google Scholar]

- Kloda, J. , Dean, P. , Maddren, C. , MacDonald, D. , & Mayes, S. (2008). Using principle component analysis to compare genetic diversity across polyploidy levels within plant complexes: An example from British Restharrows (Ononis spinosa and Ononis repens). Heredity, 100, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolář, F. , Fér, T. , Štech, M. , Trávníček, P. , & Dušková, E. (2012). Bringing together evolution on serpentine and polyploidy: Spatiotemporal history of the diploid–tetraploid complex of Knautia arvensis (Dipsacaceae). PLoS ONE, 7, e39988 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolář, F. , Štech, M. , Trávníček, P. , Rauchová, J. , & Urfus, T. (2009). Towards resolving the Knautia arvensis agg. (Dipsacaceae) puzzle: Primary and secondary contact zones and ploidy segregation at landscape and microgeographic scales. Annals of Botany, 103, 963–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. F. , & Chang, Z. Y. (1996). A cytogeographical study on Clintonia udensis (Liliaceae). Acta Phytotaxonomica Sinica, 34, 29–38. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. F. , Chang, Z. Y. , & Yuan, Y. M. (1996). The origin and dispersal of the genus Clintonia Raf. (Liliaceae): Evidence from its cytogeography and morphology. Caryologia, 49, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mantel, N. (1967). The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Research, 27, 209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzaneda, A. J. , Rey, P. J. , Bastida, J. M. , & Weiss‐Lehman, C. (2012a). Environmental aridity is associated with cytotype segregation and polyploidy occurrence in Brachypodium distachyon (Poaceae). New Phytologist, 193, 797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzaneda, A. J. , Rey, P. J. , Bastida, J. M. , & Weiss‐Lehman, C. (2012b). Environmental aridity is associated with cytotype segregation and polyploidy occurrence in Brachypodium distachyon (Poaceae). New Phytologist, 193, 797–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans, P. , & Vartienderen, P. (2004). Genotype and Genodive: Two programs for the analysis of genetic diversity of asexual organisms. Molecular Ecology, 4, 792–794. [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. , Tajima, F. , & Tateno, Y. (1983). Accuracy of estimated phylogenic trees from molecular data. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 19, 153–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obbard, D. J. , Harris, S. A. , & Pannell, J. R. (2006). Simple allelic‐phenotype diversity and differentiation statistics for allopolyploids. Heredity, 97, 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamela, S. S. , & Douglas, E. S. (2000). The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91, 7051–7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R. , & Smouse, P. E. (2006). Genalex 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology, 6, 288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R. , & Smouse, P. E. (2012). GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research an update. Bioinformatics, 28, 2537–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, T. , Roschanski, A. M. , Pannell, J. R. , Korbecka, G. , & Schnittler, M. (2011). Characterization of microsatellite loci and reliable genotyping in a polyploidy plant, Mercurialis perennis (Euphorbiaceae). Journal of Heredity, 102, 479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J. K. , Stephens, M. , & Donnelly, P. (2000). Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics, 155, 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, H. , Chen, Z. , Zhang, Z. , Wang, X. , Gao, H. , & Wang, Z. (2015). Molecular diversity and population structure of a worldwide collection of cultivated Tetraploid Alfalfa (Medicago sativa subsp. sativa L.) germplasm as revealed by microsatellite markers. PLoS ONE, 10, e0124592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A. (2014). FigTree v1.4.2: Tree figure drawing tool. [WWW document]. Retrieved from http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree

- Sampson, J. F. , & Byrne, M. (2012). Genetic diversity and multiple origins of polyploidy Atriplex nummularia Lindl. (Chenopodiaceae). Biological Science, 105, 218–230. [Google Scholar]

- Schmickl, R. , Paule, J. , Klein, J. , Marhold, K. , & Koch, M. A. (2012). The evolutionary history of the arabidopsis arenosa complex: Diverse tetraploids mask the western carpathian center of species and genetic diversity. PLoS ONE, 7, e42691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segraves, K. A. , Thompson, J. N. , Soltis, P. S. , & Soltis, D. E. (1999). Multiple origins of polyploidy and the geographic structure of Heuchera grossulariifolia . Molecular Ecology, 8, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D. E. , Buggs, R. , Barbazuk, W. B. , Chamala, S. , & Chester, M. (2012). The early stages of polyploidy: Rapid and repeated evolution in Tragopogon In Soltis P. S., & Soltis D. E. (Eds.), Polyploidy and genome evolution (pp. 271–292). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; , 35. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D. E. , Buggs, R. J. , Barbazuk, W. B. , Schnable, P. S. , & Soltis, P. S. (2009). On the origins of species: Does evolution repeat itself in polyploid populations of independent origin? Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 74, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D. E. , & Soltis, P. S. (1999). Polyploidy: Recurrent formation and genome evolution. Trends Ecology Evolution, 14, 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D. E. , Soltis, P. S. , Pires, J. C. , & Kovarik, J. (2004). Recent and recurrent polyploidy in Tragopogon (Asteraceae): Genetic, genomic, and cytogenetic comparisons. Biological Science, 82, 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, D. E. , Soltis, P. S. , & Tate, J. A. (2003). Advances in the study of polyploidy since plant speciation. New Phytologist, 161, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, H. , Rodríguez‐Echeverría, S. , & Nabais, C. (2014). Genetic diversity and differentiation of Juniperus thurifera in Spain and Morocco as determined by SSR. PLoS ONE, 9, e88996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treier, U. A. , Broennimann, O. , Normand, S. , Guisan, A. , & Schaffner, U. (2009). Shift in cytotype frequency and niche space in the invasive plant Centaurea maculosa. Ecology, 90, 1366–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, R. H. (1973). The east Asian species of Clintonia Raf. (Liliaceae). Botanical Gazette, 134, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. L. , Guo, J. , & Zhao, G. F. (2011). Chloroplast microsatellite diversity of Clintonia udensis (Liliaceae) populations in East Asia. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 39, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. L. , Li, X. , Guo, J. , Li, S. F. , & Zhao, G. F. (2010). Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of Clintonia udensis Trautv. & Mey. (Liliaceae) in East Asia. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 55, 721–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. B. , Qi, X. Y. , Gao, R. , & Wang, J. J. (2014). Microsatellite polymorphism among Chrysanthemum sp. polyploids: The influence of whole genome duplication. Scientific Reports, 4, Article number: 6730. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Z. , Tang, J. , Chen, X. Q. , Liang, S. J. , Dai, L. K. , & Tang, Y. C. (1978). Liliaceae. In Editorial Board of the Flora of China of the China Science Academy (Ed.), Flora of China. Science, 8, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss‐Schneeweiss, H. , Blöch, C. , Turner, B. , Villaseñor, J. L. , Stuessy, T. F. , & Schneeweiss, G. M. (2012). The promiscuous and the chaste: Frequent allopolyploid speciation and its genomic consequences in American daisies (Melampodium sect. Melampodium; Asteraceae). Evolution, 66, 211–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K. , Yang, M. M. , Liu, H. Yan , Tao, Y. , & Zhao, Y. Z. (2014). Genetic analysis and molecular characterization of Chinese sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) cultivars using insertion‐deletion (InDel) and simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers. BMC Genetics, 15, 35–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]