Abstract

Objective

This study reviewed the news media coverage of statins, seeking to identify specific trends or differences in viewpoint between media outlets and examine common themes.

Design

The study is a content analysis of the frequency and content of the reporting of statins in a selection of the British newsprint media. It involved an assessment of the number, timing and thematic content of articles followed by a discourse analysis examining the underlying narratives. The sample was the output of four UK newspapers, covering a broad-spectrum readership, over a six month timeframe 1 October 2013 to 31 March 2014.

Results

A total of 67 articles included reference to statins. The majority (39, 58%) were reporting or responding to publication of a clinical study. The ratio of negative to positive coverage was greater than 2:1 overall. In the more politically right-leaning newspapers, 67% of coverage was predominantly negative (30/45 articles); 32% in the more left-leaning papers (7/22 articles). Common themes were the perceived ‘medicalisation’ of the population; the balance between lifestyle modification and medical treatments in the primary prevention of heart disease; side effects and effectiveness of statins; pharmaceutical sponsorship and implications for the reliability of evidence; trust between the public and government, institutions, research organisations and the medical profession.

Conclusions

Newsprint media coverage of statins was substantially influenced by the publication of national guidance and by coverage in the medical journals of clinical studies and comment. Statins received a predominantly negative portrayal, notably in the more right-leaning press. There were shared themes: concern about the balance between medication and lifestyle change in the primary prevention of heart disease; the adverse effects of treatment; and a questioning of the reliability of evidence from research institutions, scientists and clinicians in the light of their potential allegiances and funding.

Keywords: statins, content analysis, cardiovascular medicine, medicalisation, media coverage

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of media websites for data collection may have excluded some material which was only available in the print versions and conversely included some material not available in print.

The pragmatic selection of the study timescale and media selection may have reduced the representativeness and therefore generalisability of the study; however, the sampling strategy was designed to ensure that the sources represented a reasonable range and diversity of the established newspaper media.

There was a single researcher and not a research team, leading to a potential risk of bias or incompleteness in the identification and selection of articles, and no inter-rater reliability checking of the coding scheme, which may have an impact on the validity of the analyses.

Blinding was not strictly possible, but articles were coded by a unique numerical identifier to reduce bias during the thematic analysis, and an inductive approach was applied to ensure that the themes were dictated by the evidence emerging from the texts and not imposed by the researcher.

Introduction

UK clinical guidelines recommend the use of lipid-lowering therapy for both secondary and primary prevention.1 2 This is based on published clinical trial evidence of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness1 3–8 and the extent of side effects.7–9 There is debate in the clinical literature about the merits of the widespread and growing use of statins, questioning whether the ‘right’ patients are benefiting, whether the threshold for initiation of primary preventative treatment is too low and the reliability of the evidence underpinning the guidelines.10–16 The same issues are also covered in the lay media, where, however, the nature and extent of the debate are less well documented.

There is an interaction between the lay and clinical media, with the same commentators and topics or reported, or directly speaking, in both.17–20 Importantly, there is evidence that the lay media influences health-related perceptions and behaviours, including reporting of side effects, uptake of services and adherence to medication.21–26 The Chief Medical Officer for England called for a review into how the safety and efficacy of drugs was judged, prompted by concern about the representation of statins and other drugs ‘in both the medical and general press’.27 A Danish study, using national and regional media coverage as a proxy for individual exposure, found that negative statin-related news stories were associated with both early statin discontinuation and cardiovascular mortality.28

In the light of this relationship, it is relevant to examine the portrayal of statins in the media and the messages that are being predominantly received. This study investigates the nature of the representation of statins in the newsprint media, identifying the key themes, trends, characteristics and viewpoints.

Method

A descriptive and thematic analysis of the frequency of the coverage of statins in the UK newsprint media was undertaken. Media were selected with the aim of obtaining broad-spectrum coverage reflecting a range of editorial leanings and readerships. An initial screening sample was undertaken in order to pilot the methodology and to consolidate the questions and sampling strategy for the main research.29 This identified what would be practical for one researcher to collect and enabled refinement of the range and type of outlets, the time period and the type of articles for inclusion in the main data collection. The sampling frame selected for the main study was the UK newsprint media. A purposive sampling strategy was followed, with newspapers selected on the basis that they were accessible, able to be searched and analysed by one researcher in the time available, and demographically, geographically and politically representative of a broad-spectrum readership. The selected newspapers were The Daily Mail, The Daily Mirror, The Telegraph and The Guardian (table 1). These are all national UK newspapers, recording high circulation.

Table 1.

Readership of selected newspapers 201340 41

| Category | Daily Mail | Daily Mirror | The Telegraph | The Guardian |

| Circulation | 1 863 000 | 1 058 500 | 555 600 | 204 400 |

| Average age | 58 | Not given | 61 | 44 |

| Readership 65+ | 45% | 34% | 46% | 21% |

| Gender | 51% female | 54% male | 52% male | 52% male |

| Social class ABC1* | 64% | 43% | 87% | 89% |

| Predominant geography (Mori 2005) | 83% outside London and Scotland |

North | East and South East | London |

| Predominant political stance** | Right | Left | Centre right | Centre left |

| Market designation | Tabloid | Tabloid | Broadsheet | Broadsheet |

* Social gradings A-E are based on 2011 UK census data. ABC1 represents higher & intermediate to clerical and junior occupations. ** Political stance reflects party affiliation in the most recent general election. (Right: Conservative, UKIP; left: Labour, Green; Centre right: Conservative, Liberal Democrat; Centre left: Labour, Liberal Democrat.)

Full texts of articles were searched by keyword and collected retrospectively from the websites of the selected media outlets over a continuous 6-month timeframe (1 October 2013 to 31 March 2014). The main search term was ‘statin’ (‘statins’ did not retrieve all mentions.) A further search on ‘cholesterol’, ‘cardiovascular’ and ‘heart disease’ was undertaken to confirm all relevant articles had been captured. All articles with any recorded mention of statins were screened. All types of article were included.

Articles were downloaded and printed in full. Each article was given a unique reference number, to blind the researcher to source during the analysis, and key descriptors were recorded. A thematic data analysis was then undertaken. A coding scheme provided a consistent framework for data collection and analysis and enabled independent third-party review. The exclusion criterion was peripheral mention of statins with no associated reporting or comment.

The analysis was in two parts. An initial descriptive analysis mapped the findings against the descriptive indicators, including whether the coverage was judged to be predominantly positive or negative in terms of the arguments, language and terminology.

Where the proportion of positive and negative comments appeared similar or where it was difficult to decide on the overall direction, a neutral assessment was given. A more detailed qualitative analysis then examined the nature of the discourses within the key themes, including viewpoints, assumptions and language. Outlets were then tracked back and identified in the results. A copy of the coding scheme is available as an online Supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2016-012613supp001.pdf (72KB, pdf)

There were no confidentiality issues associated with the study as all data sources were within the public domain. Ethics committee approval was not required.

Results

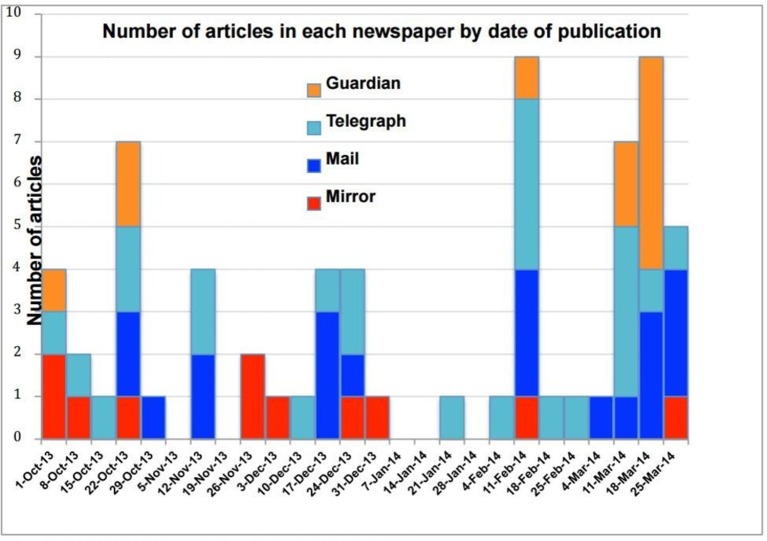

Searches identified 67 articles during the time period. A timeline showing overage by outlet by week is shown in figure 1. There is considerable variation, with peaks in coverage weeks commencing 11 February and 18 March. The NICE revised draft guidelines were published on 12 February,30 covered in 11 articles, prompting the earlier peak. A systematic review of the side effects of statins9 was widely reported a month later. In only five of the 26 weeks was there no story about statins.

Figure 1.

Coverage by outlet by week, October 2013–March 2014.

In two-thirds of articles (table 2), statins were the main topic. The majority of articles (39, 58%) were reporting or responding to publication of a clinical study.

Table 2.

Number, stance and theme of articles mentioning statins (1 October 2013 to 31 March 2014)

| The Telegraph | Daily Mail | The Guardian | Daily Mirror | Total | |

| Number of articles | 25 | 20 | 11 | 11* | 67 |

| Frequency of article type | |||||

| Study report/response | 10 (40.0%) | 13 (65.0%) | 6 (54.5%) | 10 (90.9%) | 39 (58.0%) |

| Commentary | 3 (12.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (9.0%) |

| Q&A | 2 (8.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| Personal story | 1 (4.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| News report | 1** (4.0%) | 1** (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1** (9.1%) | 3 (4.5%) |

| Letters | 4 (16.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (6.0%) |

| Expert/’celebrity’ commentator | 3 (12.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (7.5%) |

| Other | 1 (4.0%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (6.0%) |

| Statins main topic | |||||

| Main topic | 18 (72.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | 10 (90.9%) | 3 (27.3%) | 45 (67.2%) |

| Secondary topic | 7 (28.0%) | 6 (30.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 8 (72.7%) | 22 (32.8%) |

| Positive/negative | |||||

| Positive | 2 (8.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (36.4%) | 17 (25.4%) |

| Neutral | 3 (12.0%) | 2 (10.0%) | 5 (45.4%) | 3 (27.2%) | 13 (19.4%) |

| Negative | 20 (80.0%) | 10 (50.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (36.4%) | 37 (55.2%) |

*One article was excluded.

**Publication of NICE and US guidelines on the use of statins.

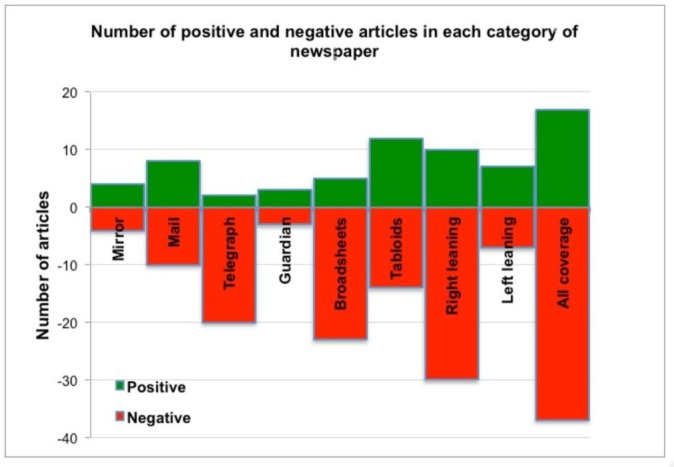

The ratio of negative to positive coverage was greater than 2:1 overall. The more right-leaning papers exhibited a ratio of 3:1 negative to positive articles, where the left leaning press had equal proportions of each. The Telegraph had the highest differential with a 10:1 ratio of negative to positive stories (figure 2). Articles on studies reporting collateral benefits (statins benefiting people with multiple sclerosis or dementia for example) were more likely to portray statins in a positive light.

Figure 2.

Positive and negative coverage.

Thematic analysis

The themes with the highest number of mentions selected for detailed analysis were medicalisation versus lifestyle modification, the effectiveness of statins in the light of their side effects and trust of those advocating statin therapy.

Medicalisation versus lifestyle modification

The term ‘medicalisation’ is used by three of the four sampled media, both in quotes from contributors and by the article authors. In most cases, it is used to denote the introduction of drug treatment for use in an otherwise apparently healthy population. It is used with an exclusively negative meaning:

‘the ‘medicalisation’ of people who are not ill… turning five million middle-aged and predominantly healthy men and women into statin-popping patients’ (Mail, 13 February 2014).

‘It is a concern to have to mass medicalise the whole of the British public in this way’ (Telegraph, 11 February 2014). Britain will be confirmed ‘the statins capital of Europe’ (Mail, 12 February 2014).

There is a language of passivity and control. People are ‘medicalised’, ‘medicated’ or ‘put on statins’ (emphasis added).

The majority of articles appear supportive of prescribing statins for those with established heart disease. The controversy centres on what proportion of those with risk factors for cardiovascular disease should receive statins as a primary preventative measure:

‘there are people who may be overweight or have raised blood pressure. They probably don’t have symptoms. They are not ill’ (Guardian, 21 March 2014).

‘we’ll be medicalising many relatively healthy patients’ (Mail, 12 February 2014) (emphasis added)

The medical profession is seen to be focusing on the medical option in preference to promoting lifestyle change:

‘(It is) ‘simpler to reach for the pad and write out a prescription’ than to dole out lifestyle advice’ (National Obesity Forum quoted in Mail and Telegraph, 25 December 2013)

The public is also indicated to be at fault:

‘There is a tendency… for patients (and doctors) to think that as long as they’re on statins, smoking or a poor diet doesn’t really matter’;

‘people will see them as a magic pill that allows them to tuck into three pizzas a night and umpteen hamburgers with impunity’ (‘leading cardiologist’ quoted in Mail, 8 March 2014, 13 February 2014)

Lifestyle measures could actually be the preferable medicine:

‘Exercise can be just as efficient as drugs in treating heart disease’ (study report, Mirror, 2 October 2013)

‘eating an apple a day is as effective as taking statins’ (medical ‘campaigner’, Telegraph, 2 March 2014)

Effectiveness and side effects of treatment

The positioning of ‘expert’ opinion is important here. Who is most qualified to determine the impact of side effects: clinician, trialist or patient?

Evidence from published studies on the extent of side effects is reported:

‘the benefits of statins greatly exceed any side effects’ (Cholesterol trialists study report, Mail, 12 February 2014).

This is directly challenged by individuals:

NICE ‘will tell you that… one in 10 000 patients… will suffer severe muscular pain…. In contrast, reliable data from the real world… backed up by anecdotal evidence from my experience as a cardiac physician suggests that the real figure… is closer to one in five.’ (cardiologist quoted in Mail, 13 February 2014)

‘I know of only three people who have been on statins—I am one of them—and we all experienced debilitating muscle aches’ (reader correspondence, Telegraph, 15 March 2014)

The ‘noise’ about side effects may produce the equivalent of a ‘nocebo effect’:

‘If we tell people about side effects,… we induce these unpleasant symptoms,… inflicting harm on our patients’;

‘We… shouldn’t scare people into experiencing side effects… or into avoiding a medication which might help them’ (‘study author’, Guardian, 14 March 2014)

Statins are portrayed as either villain or hero:

‘in years to come, statins could be seen as being as dangerous as thalidomide’ (reader correspondence, Mail, 14 November 2013)

‘Statins may reduce dementia by a third’ (study report, Telegraph, 30 December 2013)

Over the six month sample period, statins were associated with potential beneficial effects on dementia, multiple sclerosis and erectile dysfunction.

Trust

A related but distinct theme is trust. The reliability of studies or guidelines is traditionally linked to the weight of scientific evidence—usually randomised controlled trial evidence—underpinning them. However, there is an implied suspicion of the evidence based on the perceived trustworthiness of those producing or funding it. An interesting question emerges concerning which forms of evidence have the greater validity:

NICE recomendations are ‘based on solid evidence and the public should trust them’ (US study authors quoted in Mail, 13 November 2013)

‘The drug companies were saying this drug was the best thing since sliced bread’; ‘their findings are contradicted by independent surveys’ and they are ‘contrary to the experience of many Telegraph readers’ (response to draft NICE guidelines, Telegraph, 2 March 2014)

‘trials run by the drug companies… are likely to be excessively favourable’ (Harvard clinician, Mail, 24 December 2013)

The confidentiality of some of the trial data leads to suspicion of what the data contain:

There is no reason ‘to accept the analysis of the Oxford team who have seen the data at face value just because they are big and important and professors at Oxford University…. Either they don’t have a vast chunk of data or they do and they are not publishing it’ (‘Scottish GP and author’, Guardian, 21 March 2014)

Another dimension of trust is seen in the portrayal of organisations and institutions. Pharmaceutical companies are almost universally negatively portrayed. Some academic bodies are still largely to be trusted, for example

‘the respected Cochrane group’ (Guardian, 27 October 2013)

but other organisations or individuals are contaminated by association: there are

‘arrangements between Big Pharma and academic institutions (and) vested interests in the research’ (Telegraph, 15 March 2014)

Political and administrative organisations receive a mixed portrayal:

‘the government’s advice is based on a wealth of evidence. The BMJ article is based on opinion’ (Public Health England director quoted in Guardian, 23 October 2013)

‘how can we explain this big gap between… personal experience… of doctors and patients… and official bodies such as NICE?’ (Mail, 18 March 2014)

‘NICE seems to be siding firmly with the drug companies and relying on industry-sponsored statistics’ (Mail, 13 February 2014)

Family doctors receive consistently negative coverage. Medical authority is portrayed as siding with, or indirectly influenced by, the pharmaceutically sponsored institutions. Doctors are accused of

‘inexcusable deviousness’

in their methods for fulfilling screening quotas and in disguising a prescription for statins as

‘lipid tablets’ (Telegraph, 16 February 2014)

There is a risk of:

‘more aggressive prescribing of (statin) medications by family doctors, whose pay is linked to take-up of the pills among their patients’ (Telegraph, 11 February 2014).

Discussion

This study found that the newsprint media coverage of statins was substantially influenced by coverage in the medical journals of clinical studies, reports and comment. Statins received a predominantly negative portrayal overall, notably in the more right-leaning press. Specifically, there was considerable coverage of reported side effects; concern about the balance between medication and lifestyle changes in primary prevention; and a questioning of the reliability of evidence from research institutions, scientists and clinicians in the light of their potential allegiances and funding.

The findings are consistent with a number of earlier studies and also highlight some departures from previous research.

The strongest criticism of statins and their effects in the media appears to reflect very closely the arguments presented in the medical journals over the same time period, although the weighting of the arguments may differ.10–12 In the popular press, there is no discernible difference in the reporting of what the scientific community might describe as important, high-quality studies compared with the reporting of small studies, or opinion, with high potential for bias. All views are portrayed with equal weight and seriousness. Other studies have identified greater selectivity in reporting in the popular compared with the specialist media, with a greater focus on more controversial topics.31

A notable trend identified in the media is for reports of new links between, for example, statins and dementia, or statins and impotence, to be more uncritical than reports of the use of statins in preventing heart disease. With a new study, the results themselves are the story, whereas with the role of statins in the prevention of heart disease, it is the debate and controversy that is represented.

In terms of the medication versus lifestyle debate, clinical studies disagree about the extent to which health-promoting behaviours are actually affected by long-term statin use.32–34 However, the newspaper coverage contained a largely judgemental vocabulary around the selection of a medical treatment pathway, suggesting that people who take tablets or doctors who prescribe them may be abdicating personal responsibility for health.

The question of trust in institutions has also been highlighted in other research. Commentators have identified a tendency in the media to exaggerate and seek to mobilise opinion against a ‘supposed threat’ or conspiracy.35 In contrast, where previous research has placed clinicians—family doctors in particular—high in the hierarchy of public trust,21 36 this study found no evidence of positive reporting of the medical profession in relation to statins.

One question arising from this study is whether statins have a distinct status with respect to the debate. The polarisation of good drug/bad drug is not new. Other studies have reported a similarly dichotomised approach in relation to other medical treatments.22 37 There are parallels with the representation of the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, another frequently invisible ‘sickness’ addressed by long-term preventative medication.16 However, in the case of statins, the threshold for treatment appears increasingly to be driven by age rather than specific clinical indicators. (The QRisk cardiovascular risk calculator is strongly influenced by age.) Everyone could eventually become a candidate for medicalisation, however healthy their lifestyle and however low their cholesterol ratio.

The study highlights a fundamental point concerning the significance of the portrayal of medical issues in the media: is it important that even someone reading across the whole range of newspaper coverage sampled for this study would receive a negative impression of the value of the scientific evidence and the benefit of statins, when current clinical guidance recommends their use? Coverage in the popular press highlights the confusing messages projected by science and research worldwide. There is no mediating discourse leading people through the pendulum findings of one study or learned commentator after another. The ‘noise’ of the continuing debate may even be frightening people away from taking their prescribed medications and increasing cardiovascular mortality.17 28 This raises an ethical question around the desirability of presenting all viewpoints, however well or ill evidenced, at the risk of deterring people from acting responsibly with regard to their health. Other studies have suggested that there is scope for the scientific and medical worlds to articulate their messages more carefully for popular media consumption.26 37 38 Alternatively, the rawness and transparency of the debate may be a good thing. The ability to see and critique another scientist’s work is valued by researchers, and it may also be of benefit to a non-medical audience to hear the challenge and defence of each viewpoint played out in the public arena. One response is for subject experts to provide an evidence-based commentary on scientific issues of public interest, along the lines of NHS Choices’ ‘Behind the Headlines’, developed by Sir Muir Gray because ‘In the same way that people need clean, clear water, they have a right to clean, clear knowledge’.39

This study adds insight into the portrayal of preventative medications and related clinical policy, in the media. There are potential implications for clinicians, study authors, policy makers and public health practitioners. By increasing awareness of the messages their patients, readers and the public are predominantly hearing in relation to their medications, it highlights the considerable scope for all health experts to promote a more media-friendly, evidence-based narrative on health topics of public interest or concern.

Recommendations for further research include a comparison of a wider number of outlets and different areas of medicine over a longer period of time, a comparison of the medical and popular media coverage in detail and further exploration of the impact of media coverage on reader health behaviours.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JC collected the data, undertook the analysis, and is the main author of the final paper. TM had the original idea, contributed significantly to the design and development of the study, and commented on the drafts of the article. CJ, LF and ZZ commented on the drafts of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: No human subjects involved in the research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: A copy of the coding scheme is supplied as supplementary information. The original data were obtained from publicly available sources.

References

- 1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease NICE clinical guideline. 181, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. British Cardiac Society British Hypertension Society Diabetes UK HEART UK Primary Care Cardiovascular Society Stroke Association. JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 2005;91 Suppl 5:v1–v52. 10.1136/hrt.2005.079988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, NICE clinical guideline. 181, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guideline Development Group. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease, NICE clinical guideline, methods, evidence and recommendations, draft for consultation, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor F, Huffman M, Macedo A, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013. Art. No: CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012;380:581–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Finegold JA, Manisty CH, Goldacre B, et al. What proportion of symptomatic side effects in patients taking statins are genuinely caused by the drug? Systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials to aid individual patient choice. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2014;21:464–74. 10.1177/2047487314525531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Abramson JD, Rosenberg HG, Jewell N, et al. Should people at low risk of cardiovascular disease take a statin? BMJ 2013;347:f6123 10.1136/bmj.f6123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malhotra A. Saturated fat is not the major issue. BMJ 2013;347:f6340 10.1136/bmj.f6340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Godlee F. The BMJ and authors withdraw statements suggesting that adverse events occur in 18-20% of patients. British Medical Journal 2014;2014:g3306. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:526–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Staa TP, Smeeth L, Ng ES, et al. The efficiency of cardiovascular risk assessment: do the right patients get statin treatment? Heart 2013;99:1597–602. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu J, Zhu S, Yao GL, et al. Patient factors influencing the prescribing of lipid lowering drugs for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in UK general practice: a national retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e67611 10.1371/journal.pone.0067611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rose G. Rose’s Strategy of Preventive Medicine: Oxford University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldacre B. Statins are a mess: we need better data, and shared decision making, editorial. BMJ 2014;348:g3306.25134141 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldacre B. Statins have no side effects? this is what our study really found. The Guardian 2014;14. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldacre B. BadScience.net, 13 March 2014. http://www.badscience.net/2014/03/statins-have-no-side-effects-what-our-study-really-found-its-fixable-flaws-and-why-trials-transparency-matters-again/ (Accessed July 2014).

- 20. Malhotra A. BBC News. October 2013;23 http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-24625808. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duffy B, Rowden L. You are what you read? how newspaper readership is related to views. Mori Social Research Institute 2005;P32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seale C. Health and media: an overview. Sociol Health Illn 2003;25:513–31. 10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Hunsel F, van Puijenbroek E, de Jong-van den Berg L, et al. Media attention and the influence on the reporting odds ratio in disproportionality analysis: an example of patient reporting of statins. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:26–32. 10.1002/pds.1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eberth JM, Kline KN, Moskowitz DA, et al. The role of media and the internet on vaccine adverse event reporting: a case study of human papillomavirus vaccination. J Adolesc Health 2014;54(3):289–95. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Faasse K, Gamble G, Cundy T, et al. Impact of television coverage on the number and type of symptoms reported during a health scare: a retrospective pre-post observational study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001607 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grilli R, Ramsay C, Minozzi S. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilisation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002:CD000389 10.1002/14651858.CD000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davies S. Letter to the academy of Medical Sciences. 2015. Quoted in the Pharmaceutical Journal of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society 17 June 2015 Quoted in The Guardian 16 June 2015 http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jun/16/chief-medical-officer-calls-review-after-statins-tamiflu-stormhttp://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/news-and-analysis/news/englands-top-doctor-orders-review-into-how-medicines-are-evaluated/20068759.article (Accessed August 2015Accessed August 2015).

- 28. Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG. Negative statin-related news stories decrease statin persistence and increase myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 2016;37 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macnamara J. Media content analysis: its uses, benefits and best practice methodology. Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal 2005;634:1P20. [Google Scholar]

- 30. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Lipid modification Cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease draft update for consultation. NICE guideline, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hernandez JF, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, van Thiel GJ, et al. Publication trends in newspapers and scientific journals for SSRIs and suicidality: a systematic longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000290 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sugiyama T, Tsugawa Y, Tseng CH, et al. Different time trends of caloric and fat intake between statin users and nonusers among US adults: gluttony in the time of statins? JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1038 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lofgren I, Greene G, Schembre S, et al. Comparison of diet quality, physical activity and biochemical values of older adults either reporting or not reporting use of lipid-lowering medication. J Nutr Health Aging 2010;14:168–72. 10.1007/s12603-010-0030-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lytsy P, Burell G, Westerling R. Cardiovascular risk factor assessments and health behaviours in patients using statins compared to a non-treated population. Int J Behav Med 2012;19:134–42. 10.1007/s12529-011-9157-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McQuail D. Mass communication and society. The influence and effects of mass media. 94, 1977:70P15. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gale NK, Greenfield S, Gill P, et al. Patient and general practitioner attitudes to taking medication to prevent cardiovascular disease after receiving detailed information on risks and benefits of treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:12–59. 10.1186/1471-2296-12-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prosser H. Marvelous medicines and dangerous drugs: the representation of prescription medicine in the UK newsprint media. Public Underst Sci 2010;19:52–69. 10.1177/0963662508094100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Danovaro-Holliday MC, Wood AL, LeBaron CW. Rotavirus vaccine and the news media, 1987-2001. JAMA 2002;287:1455–62. 10.1001/jama.287.11.1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gray M. Behind the headlines, NHS Choices. 2011. http://www.nhs.uk/news/Pages/about-behind-the-headlines.aspx (Accessed July 2014).

- 40. NRS Readership Estimates. National Readership Survey. 2013. http://www.nrs.co.uk/latest-results/nrs-print-results/newspapers-nrsprintresults/ (Accessed March 2014).

- 41. TheMediaBriefing. 2014. https://www.themediabriefing.com/ (Accessed March 2014).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012613supp001.pdf (72KB, pdf)