Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Psychological risk factors such as stress, anxiety and depression are known to play a significant and independent role in the development and progression of CVD and its risk factors. Tai Chi has been reported to be potentially effective for health and well-being. It is of value to assess the effectiveness and safety of Tai Chi on psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and/or cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods and analysis

We will include all relevant randomised controlled trials on Tai Chi for stress, anxiety, depression, psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and cardiovascular risk factors. Literature searching will be conducted until 31 December 2016 from major English and Chinese databases. Two authors will conduct data selection and extraction independently. Quality assessment will be conducted using the risk of bias tool recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. We will conduct data analysis using Cochrane’s RevMan software. Forest plots and summary of findings tables will illustrate the results from a meta-analysis if sufficient studies are identified.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required as this study will not involve patients. The results of this study will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication, to inform both clinical practice and further research on Tai Chi and CVDs.

Discussion

This review will summarise the evidence on Tai Chi for psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and their risk factors. We anticipate that the results of this review would be useful for healthcare professionals and researchers on Tai Chi and CVDs.

Trial registration number

International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) number CRD42016042905.

Keywords: Tai Chi, well-being, stress, depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will synthesise the evidence on Tai Chi for psychological well-being and quality of life in people with cardiovascular disease and risk factors for the first time.

One limitation of this study is that significant heterogeneity may appear due to the variations in psychological measurements, durations, frequencies, styles (such as Chen, Yang, Wu and Sun) or forms (such as 24-form, 54-form, 83-form) of Tai Chi.

Another limitation of this study is that the blinding of participants and personnel might be difficult in included studies which might affect the interpretation of results.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and an estimated 17.5 million people died from CVD in 2012 representing 31% of all global deaths.1 In the UK, the total CVD mortality declined by 68% between 1980 and 2013, while the hospital admissions increased by over 46 000 between 2010/2011 and 2013/2014.2 Current statistics of premature deaths due to CVD ranges from 4% in high-income countries to an astonishing estimate of 80% of the total CVD mortality in developing countries.3 In addition, the disease burden on the individual and society comes from deaths and also from those living with CVD. The American Heart Association estimated that the total direct and indirect cost of CVD in the USA alone for 2010 was in excess of US$500 billion.4

According to the WHO,1 the major risk factors of CVD are related to lifestyles, including tobacco smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and alcohol abuse. These factors may lead to other contributing risk factors of CVD, such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, overweight and obesity. Other determinants of CVD include poverty, stress, depression, anxiety, ageing and hereditary factors.

Psychological risk factors such as stress, anxiety and depression are known to play a significant and independent role in the pathogenesis and progression of CVD and its risk factors, with many of these factors being correlated with each other.5–9 Stress research focuses on three major perspectives: environmental (focusing on stressors or life events), psychological (assessing subjective stress appraisal and affective reactions) and biological (assessing the activation of the physiological systems involved in the stress response).10 Anxiety has been defined as a stimulus, a trait, a motive and a drive, which can be differentiated into state anxiety (an emotional condition at a period of time) and trait anxiety (a personality characteristic).11 The prevalence of anxiety in people with coronary heart disease varies from 12.0% to 41.8% in men and 21.5% to 63.7% in women.12 We define depression as either elevated depressive symptoms on a validated depression scale or a formal diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Between 31% and 45% of people with coronary heart disease suffer from clinically significant depressive symptoms, and 15%–20% of them meet criteria of major depressive disorder which is roughly threefold higher than in the general population.13 It is now well established that depression is related to the incidence of CVD and is also an independent risk factor for cardiac morbidity and mortality. Therefore, psychological management is necessary for people with CVD.

Most CVDs can be prevented by addressing these risk factors mentioned above. Medical treatment is necessary for people with hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia to reduce cardiovascular risk and prevent heart attacks and strokes.1 For people with established CVD, it is important to prevent the occurrence of further cardiovascular events such as acute myocardial infarction. However, major treatments target only at physical conditions. There is still insufficient evidence to support the introduction of psychological management strategies for people with CVD including cardiac rehabilitation and exercise programmes, general support, cognitive behavioural therapy, antidepressant medication and combined approaches.9 14 Acceptable and effective psychological interventions for people with CVD and/or cardiovascular risk factors are warranted.

Tai Chi originated in China and purportedly developed by a famous martial artist Wang-Ting Chen towards the end of Ming Dynasty (17th Century AD).15 Tai Chi comprehensively incorporates the essence of Chinese folk and military martial arts, breathing and meditative techniques, Chinese philosophy of yin and yang, and traditional Chinese medicine theory.16 In recent years, studies on Tai Chi for CVDs and risk factors have flourished. An increasing amount of studies have demonstrated multiple physical and psychological benefits of Tai Chi, including reduction of stress, anxiety, depression and improving quality of life.

Five systematic reviews17–21 have reported the beneficial effects of Tai Chi on psychological well-being, including reduction of stress, anxiety and depression in wide population, but the findings showed methodological limitations of included trials, variations in study design or comparisons, heterogeneous outcomes or small sample size. Two out of the five systematic reviews only searched literature from English databases.17 21 Wang et al20 summarised and analysed 40 studies (including randomised controlled trial (RCT), non-randomised trials and observational studies), in which 29 psychological measurements were identified, and concluded that Tai Chi significantly improved psychological well-being including reduced stress, anxiety, depression and mood disturbance and increased self-esteem. Recently, more clinical trials have been published in this area. However, little is known about the effect of Tai Chi for psychological well-being and quality of life measured by validated instruments specifically in people with CVD and/or cardiovascular risk factors.

The objective of this systematic review is to assess the effectiveness and safety of Tai Chi intervention for stress, anxiety, depression, other psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and/or cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods and analysis

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Type of study

We will include only parallel RCTs and only the first phase data and outcomes of randomised cross-over trials will be used in any data analysis.

Type of participants

We will include participants aged 40 years or older with a diagnosis of a CVD (including coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, myocardial infarction and hypertension) or with cardiovascular risk factors (including hypertension, diabetes and/or dyslipidaemia). No limitation of gender will be applied.

Type of intervention

Any types of Tai Chi will be eligible, regardless of the forms (such as 24-form, 54-form, 83-form Tai Chi) or styles (such as Chen, Yang, Wu and Sun). The duration should be at least 1 month with a frequency at least once per week.

Type of control

No treatment, other forms of exercise or conventional treatment will be eligible. Comparisons will also include a co-intervention if applied in all arms.

Type of outcome

The primary outcomes are psychological status of stress measured by validated instruments and adverse events. The secondary outcomes are other psychological status including anxiety, depression, mood disturbance, self-esteem and quality of life measured by validated instruments.

Search strategies

We aim to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (eg, published, unpublished, in press or in progress). The English searching terms will include ‘Tai Chi’, ‘Tai Chi Chuan’, ‘Tai Chi Chih’, ‘ta’i chi’, ‘Tai Ji Quan’, ‘taijiquan’, ‘cardiovascular disease’, ‘coronary heart disease’, ‘stroke’, ‘heart failure’, ‘hypertension’, ‘high blood pressure’, ‘diabetes’, ‘dyslipidaemia’, ‘high cholesterol’, ‘randomized controlled trial’, ‘randomised controlled trial’, ‘controlled clinical trial’, ‘randomly’, ‘clinical’, ‘trial’, ‘random’, ‘randomised’ and ‘randomized’. The Chinese searching terms will include Tai Chi (‘Tai_ji’, or ‘Tai_ji_chuan’), cardiovascular disease (‘Xin_xue_guan_bing’), cardiovascular risk factors (‘Gao_xue_ya (hypertension)’, ‘Tang_niao_bing (diabetes)’, ‘Gao_xue_zhi (dyslipidaemia)’) and randomised (‘sui_ji’). Examples of detailed search strategies for one English database and one Chinese database are available in table 1. We will apply a similar strategy for other electronic databases.

Table 1.

Search strategies

| Database | Number | Search items |

| PubMed | #1 | (Title/Abstract) (‘Tai Chi’ OR ‘Tai ji’ OR ‘Tai Chi Chih’ OR ‘Ta’i chi’ OR ‘taichi’ OR ‘tai chi chuan’ OR ‘taichi chuan’ OR ‘taiji’ OR ‘Tai Ji Quan’ OR ‘taijiquan’ OR ‘martial arts’) |

| #2 | (Title/Abstract) (‘cardiovascular disease’ OR ‘coronary heart disease’ OR ‘stroke’ OR ‘heart failure’ OR ‘hypertension’ OR ‘high blood pressure’ OR ‘diabetes’ OR ‘dyslipidaemia’ OR ‘high cholesterol’) | |

| #3 | (All fields) (‘randomized controlled trial’ OR ‘randomised controlled trial’ OR ‘controlled clinical trial’ OR ‘randomly’ OR ‘clinical’ OR ‘trial’ OR ‘random’ OR ‘randomised’ OR ‘randomized’) | |

| #4 | #1 and #2 and 3# | |

| CNKI | #1 | (Abstract) (‘Tai_ji’ (Tai Chi) OR ‘Tai_ji_quan’ (Tai Chi) |

| #2 | (Abstract) (‘Xin_xue_guan_bing’ (cardiovascular disease) OR ‘Guan_xin_bing’ (coronary heart disease) OR ‘Zhong_feng’ (stroke) OR ‘Nao_zu_zhong) (stroke) OR ‘Xin_Shuai’ (heart failure) OR ‘Gao_xue_ya’ (hypertension) OR ‘Tang_niao_bing’ (diabetes) OR ‘Gao_xue_zhi’ (dyslipidaemia)) | |

| #3 | (All fields) (‘sui_ji’ (randomized or randomised)) | |

| #4 | #1 and #2 and 3# |

CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure.

We will conduct electronic searches from the following databases until 31 December 2016: Cochrane Heart Review Group Specialised Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Library (2017, Issue 1), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) (from 1946), Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE) (from 1974), PubMed (from 1966), Sino-Med database (CBM, from 1978), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, from 1979), VIP Journal Integration Platform (VJIP, from 1989) and Wanfang Data Chinese database (from 1985).

We will also search the following trials registers to identify those completed trials and request for unpublished data until 31 December 2016: Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com), US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.clinicaltrials.gov), Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry platform (www.who.int/trialsearch). Additional clinical trials will be identified by searching the reference lists of relevant trials. Authors of identified studies will be also contacted to identify other studies.

Data selection and extraction

Selection of studies

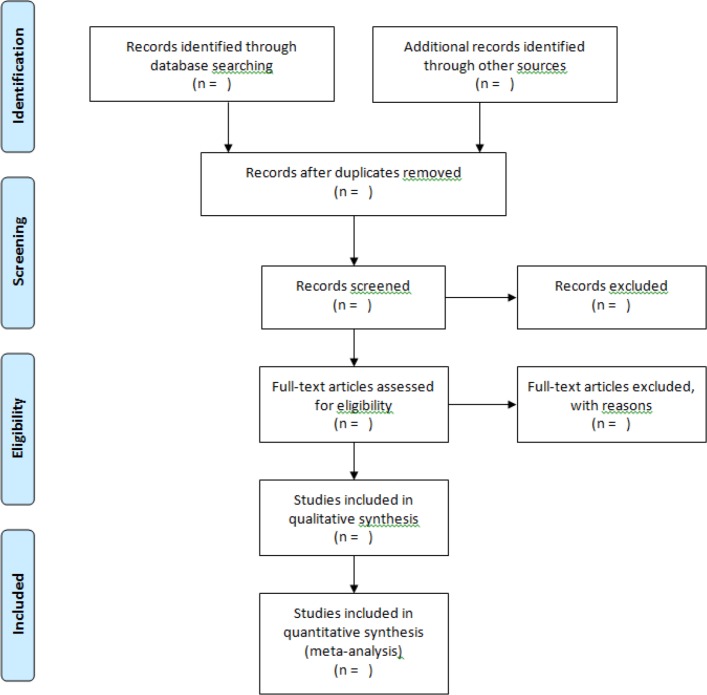

Two authors (GY and WL) will screen the titles and abstracts independently. We will retrieve full texts of all potentially relevant studies. Any disagreement about the selection of studies will be resolved by discussion, and another author will arbitrate when necessary. The selection procedure is shown in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. The PRISMA statement is used worldwide to improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (GY and WL) will extract the data from the included trials independently by using Epidata V.2.8 software. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion with a third author. The extracted data will include the following information: (1) publication information: authors, country, journal name and year of publication; (2) study designs: method of random number generation and allocation concealment, details of blinding methods; (3) participants: sample size, characteristics of participants (eg, age, gender, duration of disorder and severity of disorder); (4) intervention: type and/or form of Tai Chi, details of treatment and control; (5) outcome data: outcomes measures, main data of the outcomes. In case of missing data or having unclear information, we will contact the original authors to clarify the information. A predefined data extraction form developed based on the recommendation of the Cochrane Collaboration22 is shown in online supplementary table 1.

bmjopen-2016-014507supp001.pdf (172.3KB, pdf)

Quality assessment

We will use the risk of bias tool provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions23 to assess the methodical quality of included studies. We will assess the following categories of bias for each study: selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting) and other bias. We will not report performance bias, considering the difficulty to blind the participants and personnel in Tai Chi study. For each item, there are three potential bias judgements: ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’, or ‘unclear risk’. A clinical trial meeting all criteria will be judged as having a low risk of bias, a trial meeting none of the criteria will be judged as having a risk of bias, and a trial with insufficient information to judge will be classified as unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements will be resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third author where necessary.

Data synthesis

We will summarise data using risk ratios with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes or mean difference with 95% CI for continuous outcomes. We will assess clinical heterogeneity according to the characteristics of the included studies and the participants, details of the intervention or control, and types of outcome measurements. We will assess statistical heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic, and heterogeneity will be regarded as substantial if the I2 statistic is >50%.

We will perform statistical analyses by the Cochrane’s Review Manager software (V.5.3). We will pool data if the I2 statistic is <75% and the clinical heterogeneity among trials is acceptable. We will use random-effects model to conduct the meta-analysis unless the I2 statistic is <25%. Forest plots will visualise the results of the meta-analysis if there are more than 10 included trials in one meta-analysis.

Subgroup analyses

To explore whether the treatment effects are different in different subgroups, we plan to conduct subgroup analyses for different psychological measurements, durations, frequencies, styles (such as Chen, Yang, Wu and Sun) or forms (such as 24-form, 54-form and 83-form Tai Chi) of Tai Chi, if sufficient studies are identified. We will also calculate the incidence rates of different types of adverse events.

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the robustness of evidence, we will perform sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of studies with high risk of bias. We will compare the results to decide whether studies with lower quality should be excluded on the basis of sample size, strength of evidence and influence on pooled effect size.

Grading the quality of evidence

We will generate ‘Summary of findings’ (SoF) tables for the primary outcomes using GRADEPro software (V.3.2), to assist health decision making for individual patients. The SoF tables will demonstrate the overall quality of the body of evidence for clinical outcomes only from results of meta-analysis, by using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias).

Ethics and dissemination

Formal ethical approval is not required because all data used in this study will be anonymous with no concerns regarding privacy. This systematic review will summarise the evidence on the effectiveness and safety of Tai Chi for psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and CVD risk factors. The results of this study will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed journal for publication.

Discussion

Results from this systematic review will be valuable for clinical practice and research on Tai Chi and CVD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that will examine Tai Chi on psychological well-being and quality of life in people with CVD and/or CVD risk factors. The findings of this systematic review may be applied in clinical practice for the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of CVDs. Gaps in the literature will be identified to provide implications for future research on Tai Chi for CVD.

One limitation of this study is that significant heterogeneity may appear due to the various styles (such as Chen, Yang, Wu and Sun) and forms (such as 24-form, 54-form and 83-form Tai Chi) of Tai Chi, durations and frequencies. We plan to conduct subgroup analyses to explore the differences between different subgroups. Another limitation of this study is that performance bias of included studies might be at high risk, because blinding of participants and personnel in included studies is unlikely. We plan to report the blinding of outcome assessment, and conduct sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of studies with high risk of bias.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GY, NK and DC designed and conceived the study. GY drafted and revised the study protocol with contributions from WL, HC, NK, JL, AB, HK and DC. GY and WL will conduct literature search and selection. GY and WL will independently perform data extraction and assessment of quality. GY will conduct the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript of the study protocol.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. However, the first author (GY) was supported by the Research Training Scheme from Western Sydney University, International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (IPRS) and Australian Postgraduate Award (International) from Western Sydney University.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. WHO. Cardiovascular disease (CVDs). 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en (accessed 05 Sep 2016).

- 2. Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Wilkins E, et al. Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart 2016;102:1945–52. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2010 update. Circulation 2010;121:e46–e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Albus C. Psychological and social factors in coronary heart disease. Ann Med 2010;42:487–94. 10.3109/07853890.2010.515605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nekouei ZK, Doost HT, Yousefy A, et al. The relationship of Alexithymia with anxiety-depression-stress, quality of life, and social support in coronary Heart Disease (A psychological model). J Educ Health Promot 2014;3:68 10.4103/2277-9531.134816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Player MS, Peterson LE, disorder A. hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: a review. Int J Psychiatry Med 2011;41:365–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiltink J, Beutel ME, Till Y, et al. Prevalence of distress, comorbid conditions and well being in the general population. J Affect Disord 2011;130:429–37. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lavie CJ, Menezes AR, De Schutter A, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training on psychological risk factors and subsequent prognosis in patients with cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:S365–S373. 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.07.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee EH. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res 2012;6:121–7. 10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allahverdipour H, Asgharijafarabadi M, Heshmati R, et al. Functional status, anxiety, cardiac self-efficacy, and health beliefs of patients with coronary heart disease. Health Promot Perspect 2013;3:217–29. 10.5681/hpp.2013.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pająk A, Jankowski P, Kotseva K, et al. Depression, anxiety, and risk factor control in patients after hospitalization for coronary heart disease: the EUROASPIRE III Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013;20:331–40. 10.1177/2047487312441724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huffman JC, Celano CM, Beach SR, et al. Depression and cardiac disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and diagnosis. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2013;2013:1–14. 10.1155/2013/695925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, et al. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1365–72. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. LX G, Shen JZ. Chen Style Tai Chi. Beijing: People’s Sport Publishing House of China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tang H, LX G. The history and development of Tai Chi : Study on Tai Chi. Beijing: People’s Sport Publishing House of China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma M, Haider T. Tai chi as an alternative and complimentary therapy for anxiety: a systematic review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2015;20:143–53. 10.1177/2156587214561327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang F, Lee EK, Wu T, et al. The effects of tai chi on depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med 2014;21:605–17. 10.1007/s12529-013-9351-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chi I, Jordan-Marsh M, Guo M, et al. Tai chi and reduction of depressive symptoms for older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:3–12. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00882.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, et al. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2010;10:23 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang WC, Zhang AL, Rasmussen B, et al. The effect of Tai Chi on psychosocial well-being: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2009;2:171–81. 10.1016/S2005-2901(09)60052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Training C. Data collection forms for intervention reviews. http://training.cochrane.org/resource/data-collection-forms-intervention-reviews (access 05 Aug 2016).

- 23. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews ofInterventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014507supp001.pdf (172.3KB, pdf)