Abstract

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of blindness and low vision among older adults. Previous research shows a high prevalence of distress and disruption to the lifestyle of family caregivers of persons with late AMD. This supports existing evidence that caregivers are ‘hidden patients’ at risk of poor health outcomes. There is ample scope for improving the support available to caregivers, and further research should be undertaken into developing services that are tailored to the requirements of family caregivers of persons with AMD. This study aims to implement and evaluate an innovative, multi-modal support service programme that aims to empower family caregivers by improving their coping strategies, enhancing hopeful feelings such as self-efficacy and helping them make the most of available sources of social and financial support.

Methods and analysis

A randomised controlled trial consisting of 360 caregiver–patient pairs (180 in each of the intervention and wait-list control groups). The intervention group will receive the following: (1) mail-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy designed to improve psychological adjustment and adaptive coping skills; (2) telephone-delivered group counselling sessions allowing caregivers to explore the impacts of caring and share their experiences; and (3) education on available community services/resources, financial benefits and respite services. The cognitive behavioural therapy embedded in this programme is the best evaluated and widely used psychosocial intervention. The primary outcome is a reduction in caregiver burden. Secondary outcomes include improvements in caregiver mental well-being, quality of life, fatigue and self-efficacy. Economic analysis will inform whether this intervention is cost-effective and if it is feasible to roll out this service on a larger scale.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the University of Sydney human research ethics committee. Study findings will be disseminated via presentations at national/international conferences and peer-reviewed journal articles.

Trial registration number

The trial registration number is ACTRN12616001461482; pre-results.

Keywords: randomised controlled trial, carer, intervention, health outcomes, cognitive behavioural therapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

It is an innovative study as it is the first to implement and evaluate a comprehensive support service tailored to family caregivers of persons with age-related macular degeneration.

Randomised controlled trial design with a wait-list control group.

Translation of evidence-based interventions to practice—there is evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy can be effective in reducing caregiver burden and distress, and it is the most widely used psychosocial intervention.

It is a multi-component intervention, and prior research has shown that these are more effective than single interventions because they use several techniques and addresses a variety of caregiver needs.

Recruitment of participants is confined to only one state in Australia.

Blinding of the intervention to participants and project staff (ie, study coordinator) is not possible.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive, chronic disease of the central retina and is a leading cause of blindness and low vision among older adults.1 Advanced AMD, including neovascular AMD (wet) and geographic atrophy (late dry), is associated with substantial, progressive visual impairment.2 Visual impairment from AMD often means that patients have a reduced ability to engage in everyday activities and family members are often called on to provide physical and emotional support.3–6 Caring for loved ones with vision loss is burdensome and often leaves the caregiver exhausted and at risk of health problems.5 7 8 A UK study9 showed an elevated level of caregiver burden associated with caring for family with wet AMD, which was equivalent to the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis,10 11 and higher than for patients with colorectal cancer.9

We had previously conducted a cross-sectional survey of 500 caregivers of persons with wet AMD and showed a higher than expected prevalence of elevated emotional distress (>50%; n=280), including feeling sad, frustrated and/or isolated in this cohort.7 This finding underscored the difficulty of coping with the challenges related to assisting persons with advanced AMD. If undetected and untreated, negative outcomes related to caregiver distress could persist or worsen over time.5 Furthermore, healthcare providers are often forced to neglect caregivers and place priority on service delivery for their patients due to budgetary and strategic planning priorities.12 This could lead to clinically elevated anxiety/ stress, resulting in a greater overall burden on informal caregivers.12

Over half of the surveyed caregivers of people with wet AMD in our previous study (n=295) also neglected their own needs and personal or family interests and had to make unwelcome changes to one or more areas of their lives (eg, retirement plans).7 This self-perceived disruption to the social support that caregivers receive from their informal network of family and friends, as well as the formal network (eg, paid employment), as a result of caring for someone with AMD could perpetuate negative outcomes in caregivers.7 The qualitative analyses component of our study13 showed that significant sacrifices were made by the caregiver in order to meet the needs of the care recipient with late AMD. This could also add to the burden and distress experienced by the caregiver. Finally, our study showed that very few family caregivers sought or received respite, and this added burden can have a negative impact on the relationship between the caregiver and care recipient.13

Despite the importance of providing information and support to help family caregivers, interventions to increase support for family caregivers have lagged far behind those provided for patients with AMD.14 There is ample scope for improving the support available to caregivers, and further research should be undertaken into developing services that are tailored to the requirements of family caregivers.15 Early intervention, awareness programs and coordination of community resources could alleviate caregiver distress.7 There is strong consensus that, once information needs are met, family caregivers are likely to benefit from additional interventions such as improving their problem solving skills and extending their social support network.16 Specifically, psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can decrease caregiver distress, by fostering a more efficient, systematic approach to caregiving that enhances personal resources such as motivation and self-efficacy when providing care for a family member.5 17–22 CBT is a recognised efficacious strategy, and it is designed to help the client develop skills they can use outside of the therapy session and continue using when therapy ends.17–20 Moreover, mail-delivered CBT (M-CBT) involving written materials being posted to older caregivers is optimal, as it allows them to review the materials as often as needed and at their own pace.23 In randomised controlled trials (RCTs), M-CBT has established efficacy against control in a wide range of disorders.24 25

The proposed intervention study is novel as it will be the first to implement and evaluate a comprehensive support service tailored to the family caregivers of individuals with AMD. The intervention includes M-CBT and a telephone-delivered group therapeutic programme (facilitated by a professional counsellor), which will effectively consolidate the psychoeducation, as well as educational materials on community support, respite services and caregiver financial entitlements and benefits. The study will be a two-arm RCT with an economic evaluation. This study was codeveloped with key stakeholders or partner organisations: Macular Disease Foundation Australia (MDFA) and Carers NSW. MDFA is the national peak body representing people with macular disease, their families and caregivers, and Carers NSW is a statewide organisation representing informal caregivers. The current study aims to improve the design and delivery of these organisations’ existing support services and programs in a way that makes it easier for family caregivers to have timely access to a coordinated, multi-component intervention targeting drivers of caregiver stress and burden. A unique aspect of this study is that lay MDFA staff will be trained in the principles of CBT. MDFA currently runs support services from their Sydney (Australia) office for clients with AMD and their family members and/or caregivers. There is evidence to support lay providers without any healthcare experience delivering CBT, under the supervision of experts.23

The primary hypotheses assert that the multi-modal intervention will lead to significant reductions in caregiver burden (primary study outcome) and improvements in health-related quality of life (QOL), fatigue, self-efficacy, life satisfaction and mental and emotional well-being, (secondary outcomes). A high rate of adherence and participant satisfaction with the multi-modal intervention is also hypothesised, with delivery both acceptable and feasible to stakeholder organisations. Finally, the intervention is hypothesised to be cost-effective when compared with usual care, when considering health outcomes for family caregivers.

Methods

Study design and participants

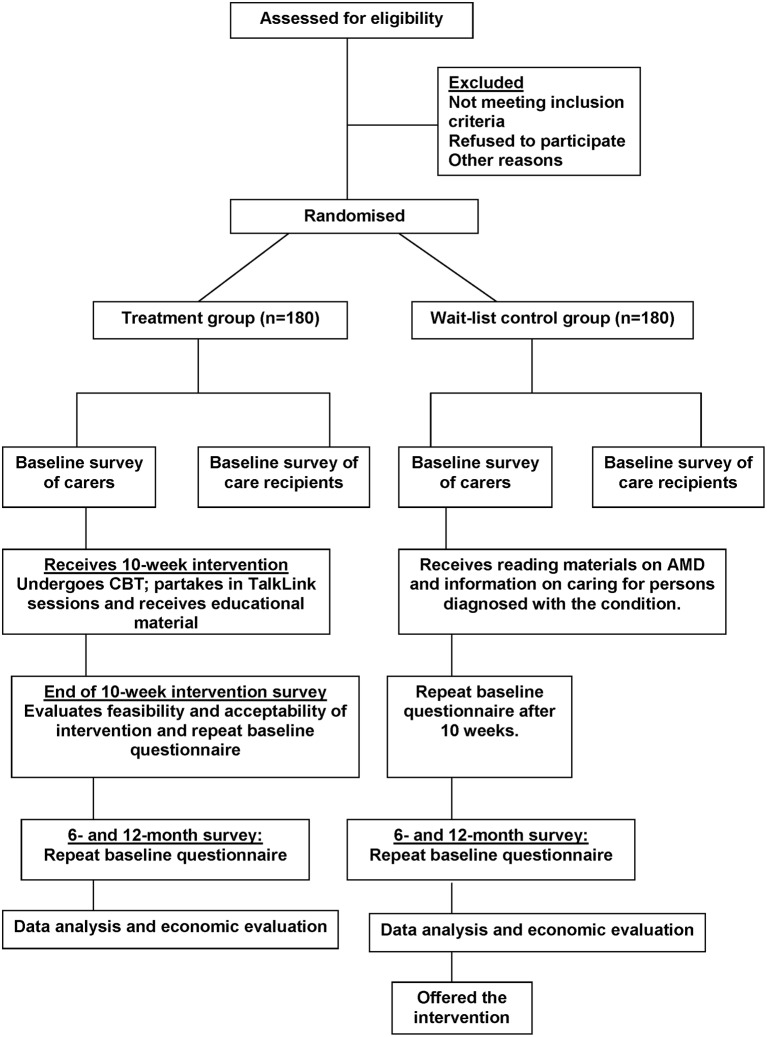

This ongoing study is designed as a multi-site, two-arm RCT, with an intervention group and a wait-list control group (figure 1). The protocol is developed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials recommendation.26 It is a 3-year study, and recruitment commenced in January 2017. This study aims to recruit participant pairs comprising a family caregiver (related to an individual diagnosed with AMD) and the care recipient (individual diagnosed with AMD). A family caregiver will be defined as ‘any person who, without being a professional or belonging to a social support network, and in some way, is directly implicated in the patient’s eye care or is directly affected by the patient’s health problem.’9

Figure 1.

Flowchart of randomised controlled trial. AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

Eligibility of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adult aged ≥18 years.

Family caregiver to an individual diagnosed with AMD and related to the care recipient (eg, spouse, child or sibling).

Willing to engage in a 10-week therapeutic intervention over a 3-month period.

Exclusion criteria

Family caregivers lacking sufficient fluency in spoken English to engage in therapy.

Recruitment

Participant pairs will be recruited primarily from private eye clinics in Westmead and Liverpool (Sydney, New South Wales, Australia). Recruitment involves an opt-in two-step process for a participant pair. Consent for participation is required from both the caregiver and care recipient. Step 1 involves screening for interest in participating in the research via either: (1) the study coordinator discussing the study with potential participants attending the eye clinic or (2) advertising the study through MDFA and Carers NSW newsletters and clients self-referring as a result of the provision of information. The advertisement will cover ‘possible emotional strain and stress’ associated with caring and the treatment’s aims of ‘improving emotional well-being and coping.’

Step 2 involves providing further information about the study via the study information sheet and obtaining written consent for the participant by either: (1) providing the information sheets, consent forms and baseline questionnaires to potential participant pairs attending the eye clinic (this will be completed at the clinic or mail returned with a reply-paid envelope) or (2) telephoning the potential participant to further discuss the research, followed by posting information sheets, consent forms and baseline questionnaires to people who have indicated willingness to participate. Loss of contact will be minimised by asking for multiple contact methods.

Randomisation and blinding

All participants will be randomly assigned to one of two groups: (i) multi-modal treatment or (ii) wait-list control (figure 1). The randomisation sequence will be generated centrally using permuted blocks of mixed size, stratified by recruitment source (clinic versus self-referral as a result of responding to MDFA and Carers NSW advertisements), to ensure equal numbers while maintaining an unpredictable sequence. Assignments to the intervention or control group will be managed centrally, separately from recruiting and treating staff, in order to ensure that a randomisation number and group is assigned and recorded for each recruit before their allocation becomes apparent.

Intervention group

The intervention group will receive a multi-modal support service programme consisting of: (1) a brief M-CBT treatment to be delivered fortnightly as five individual modules and (2) five Talk-Link group counselling sessions (an existing Carers NSW support service). The Talk-Link Counselling and M-CBT will occur weekly on an alternating basis (ie, week 1: M-CBT, week 2: Talk Link, week 3: M-CBT, and so on). The whole intervention will be conducted over 10 weeks (table 1).

Table 1.

Contents of the 10-week multi-modal treatment, comprising five cognitive behavioural therapy modules alternated with five Carers NSW Talk-Link group counselling sessions

| Name of the CBT module | CBT module inclusions | Talk-Link session |

| Session One Psychoeducation: AMD education and introduction to CBT |

|

Introduction

|

| Session Two Stress response and mood |

|

Coping with stress

|

| Session Three Sleep, general well-being and scheduling pleasant events |

|

Self-care

|

| Session Four Identifying and challenging negative thoughts |

|

Loss, grief and gain

|

| Session Five Problem solving, resiliency and self-efficacy |

|

Communication

|

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy.

M-CBT of fortnightly modules (table 1) formatted in Microsoft PowerPoint, with additional homework worksheets and accompanying templates for practising acquired skills, will be mailed to participants in the intervention group. Each module will target a specific stressor and/or train a new adaptive coping method (table 1) and will be supported by targeted homework assignments for the caregiver to practice between sessions. These will draw on standard CBT practice and on a number of additional sources including published trials, empirical studies and treatment guides.17–20 Participants will be telephoned following each M-CBT module for a brief conversation (5–10 min) aimed at: (1) addressing any queries regarding the information presented in the most recent module, (2) encouraging the learning and practising of skills from the previous module, (3) normalising the challenges of acquiring new skills, (4) emphasising the importance of the consistent practice of newly acquired skills for positive impact and (5) reminding participants in the case of unread materials. We will also ask participants how much time they spent on each module that week including reading the materials and completing the related homework sheets. Calls will be logged for each participant. The educational materials sent out to participants will aim to increase their knowledge about support and respite services and financial entitlements and benefits including how best to access them, which has been previously shown to increase caregivers’ sense of competence and reduce depression.14

Participants in the intervention group will be asked to complete a form prior to participating in the Carers NSW Talk-Link group sessions to identify the issues they might want to discuss (table 1) and to also reinforce CBT skills taught in the prior week. These will then be developed into weekly topics to guide group discussions. Information/ newsletters will be provided by the facilitators. Using teleconferencing, a group of six to eight caregivers and two trained facilitators will converse over the telephone, at the same time each week, to explore issues around caring for someone with AMD. These sessions will last for 1 hour.

Control group

During the treatment phase, the active wait-list control group will receive reading materials concerning AMD and caring for persons diagnosed with the condition. All control participants will be offered the opportunity to receive the multi-component intervention after the study ends (12–18 months after inclusion).

Measurement of covariates

A preintervention baseline questionnaire will obtain demographic and health-related information (ie, covariate data) from all family caregivers: age, sex, years of education, employment status, living arrangements, marital status, whether they are the sole caregiver, relationship to care recipient and their own health status (eg, subjective self-rated health and any chronic conditions that they have). Follow-up assessments will be conducted by postal questionnaires for all participants (caregivers only and not care recipients) from both RCT arms: immediately after completion of the 10-week programme and 6 and 12 months after initiation of the intervention (figure 1).

General caregiving activities will be assessed by asking the caregiver whether they performed any of the basic (eg, toileting, feeding, dressing, grooming) and instrumental daily living activities (eg, housekeeping, food preparation, shopping, telephone usage and transportation) for their care recipient using a validated questionnaire.27 In relation to each of these activities, they will be asked to report whether they gave: (a) no help or little help given, (b) moderate amount of help given, (c) high amount of help given or (d) not applicable. For eye-related activities that the caregiver assisted with, questions will quantify the impact of the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy received by the care recipient, if applicable: the number of appointments attended, the average time taken for appointments, time taken away from work and loss of income. Caregivers will be asked to detail the frequency (1 day/week; 2–3 days/week; 4–6 days/week; 7 days/week; 1–3 days/month or other) and duration of care (<1 hour; 1–2 hours; 3–5 hours; 5–8 hours; >8 hours or other) that they generally provide. The caregiver will also report the level of dependency of the care recipient on them, by choosing one of the following: (a) not at all dependent, (b) somewhat dependent, (c) moderately dependent, (d) very dependent or (e) extremely dependent.

The following information related to care recipients (patients with AMD) will be collected through the eye clinic records: visual acuity in the better eye, type of AMD (wet or dry AMD), number of anti-VEGF injections to date, number of clinic appointments and total follow-up period. A brief questionnaire will also be administered to care recipients at baseline, in order to collect information on socio-demographic details (age, sex, ethnicity, education, employment status, living arrangements and marital status), any other eye diseases (eg, cataract, glaucoma) and co-morbid chronic conditions they may have from, for example, heart disease, stroke, diabetes or arthritis. The questionnaire will also determine self-reported vision-related health status, using the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ-25).28 This is a 25-item scale used to generate a single composite score from 0 to 100 (100 is maximum visual function).9

Outcome measurement

Outcome data will be obtained from all randomised study participants using validated questionnaires or tools conducted at baseline, 10 weeks and 6 and 12 months. Subjective caregiver burden is the primary outcome and will be measured using the Caregiver Burden Scale (CBS) (table 2). Secondary outcomes (ie, fatigue, depressive symptoms, health-related QOL (EQ-5D-5L) and self-efficacy) are also detailed in table 2. Furthermore, caregivers will indicate their overall QOL on a linear analogue uniscale from 0 (worst possible) to 10 (best possible). Caregivers will be asked to identify whether caring for a family member with AMD created any specific problems, including: feeling tired, anxious, stressed, sad and/or depressed; impediments to employment, retirement, social activities and travel plans; and/or relationship problems as a result of the caregiving experience.

Table 2.

Validated instruments to determine specific caregiver outcomes collected at baseline: after completion of the 10-week treatment programme and 6 and 12 months postintervention in family caregivers from both randomised controlled trial arms

| Scale/ Tool | Approach taken | Outcome evaluated |

| Caregiver Burden Scale12 30 |

|

|

| Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10)32 |

|

|

| General Self-Efficacy Scale33 |

|

|

| Fatigue Severity Scale34 |

|

|

| EQ-5D-5L35 |

|

|

Individual participant consent will be sought from caregivers for Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) data linkage. Permission will be sought to link data from 12 months prior to the intervention and up until 1 year after the intervention. Hence, health-related resource use data (eg, medical consultations and prescription use) will be compared between the two RCT arms and will contribute to the economic evaluation. To protect the participants’ privacy, all outcome data will be kept in a password-protected file that is separate from the document containing the participants’ names and identification codes. All documents related to the study will be stored in restricted-access facilities or locked cupboards and on restricted-access servers and password-protected personal computers and files as per University of Sydney human research ethics committee (HREC) requirements.

Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention

Treatment acceptability in the intervention arm will be assessed immediately after completion of the 10-week multi-modal treatment by asking participants to rate their satisfaction with the following: (1) overall support service programme they received, (2) CBT modules they completed and (3) adherence to the programme. Participants will respond to these three questions using a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied.’ Participants will also be asked to respond with yes/no to the following questions: (1) “Would you feel confident in recommending this treatment to a friend?”; (2) “Was it worth your time participating in this programme?” Finally, participants will be asked to specify which components of the programme they found most useful or valuable, and suggestions will be elicited on how the programme could be improved further. Moreover, the percentage of people who enter the study compared with the total number to whom participation is offered and the follow-up rate achieved will also be determined. Treatment feasibility will be broadly assessed based on preliminary outcomes achieved: cost-effectiveness of the intervention, combined with the ease with which support staff could support participants.

Economic evaluation

The analysis will be conducted from a societal perspective and will include costs incurred by individuals and healthcare providers. This perspective will be taken because the cost consequences of this intervention may extend beyond the domain of healthcare. This will be a ‘within-trial’ economic evaluation carried out within the timeframe and context of the trial and will determine the cost–utility of this support service compared with usual care. We will determine the cost per person to deliver the support service using a bottom-up approach. This will include the cost of training MDFA staff, telephone consults, educational materials and other consumables. These will be valued at market rates and presented in 2017 $A. This will enable us to determine the cost of wider roll out of the programme. Direct healthcare costs will be determined through patient-level linkage to MBS and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Healthcare resource use during the trial will include (1) primary and secondary healthcare consultations and admissions and (2) use of medications, including antidepressants and anxiolytic medications. Healthcare costs will include both government contributions to healthcare plus any patient out-of-pocket expenses. We will also measure and value time contributions of caregivers to attend the course and take part in discussion groups, using median wage rates.

Participants’ health states will be captured using the five domains of the EQ-5D-5L, namely, mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The responses on each domain of the EQ-5D-5L will be converted into utility values using a valuation algorithm for the Australian population.29Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) will be determined over the duration of the trial from the summation of mean utility x time interval between EQ-5D administration times. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in $A/QALY will be determined in the intervention compared with control. Bootstrapping will be used to estimate a distribution of the joint uncertainty in mean costs and outcomes and to calculate the CIs around the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. One-way sensitivity analysis will be conducted around key variables. A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve will be derived that summarises the probability of the intervention being cost-effective based on willingness to pay per QALY gained.

Sample size considerations

We plan to recruit 360 caregiver–patient pairs (180 in each RCT arm) over 4–6 months. Allowing 20% loss to follow-up due to changes in the status of care recipients or death/dropout of caregivers, we will have 288 caregivers available for analysis. For our primary endpoint (caregiver burden scores), 194 available caregivers provide 80% power to detect a moderate and clinically meaningful effect size of 0.5 SD of the intervention on caregiver burden, after allowing for full compliance of 81%, at α=0.05. An 81% full compliance level represents 90% of recruits in the intervention arm actively taking up the educational and support programme, among whom 90% actively practice the strategies learnt. We have chosen to recruit the higher number of 288 available caregivers, so that we will additionally be able to estimate rates of uptake, acceptance, satisfaction and improvement with intervention with high precision (standard errors <6%) and have well-powered secondary analyses including an effect size of 0.5 of intervention on mean overall QOL and a difference of 20% vs 40% between intervention and control groups in the proportion reporting specific negative impacts of caregiving.

Data collection and analysis plan

All data will be collected using questionnaire booklets and data collection sheets and will be subsequently entered into a secure online platform, called Research Electronic Data Capture. Primary and secondary study endpoints will be analysed by intention to treat. The primary study endpoint will be postintervention change from baseline in CBS scores. The primary analysis will test for difference between intervention and control groups in postintervention change from baseline using linear mixed models for repeated measures. Secondary analyses will directly test change in scores at each follow-up within the intervention and control groups and test for difference between intervention and control groups in the average of the three postintervention CBS scores. The percentage of individuals within intervention and control arms who demonstrate a large change in caregiver burden, defined as a change of half an SD or more, will be estimated with 95% CI. Secondary endpoints are: percentage of participants reporting overall satisfaction with the intervention and each major subcomponent, percentage of participants completing the overall programme and each major subcomponent, change from baseline in QOL, fatigue and self-efficacy scores and postintervention frequency of depressive symptoms.

Differences between the intervention and control groups in individual EQ-5D-5L domain and depression outcomes will be tested using χ2 tests, and mean postintervention level of caregiver burden, fatigue, self-efficacy, depressive symptoms and general health will be tested using two-sample t-tests. Rates of uptake, continued participation, acceptability and satisfaction with intervention will be estimated with 95% CI. Associations between baseline recipient and caregiver characteristics, treatment experience and postintervention outcomes will be explored using linear mixed models for repeated measures. Baseline characteristics of the intervention and control groups will be examined.

Safety measures and endpoint

A clinical psychologist (AC), experienced in the assessment and treatment of mental health disorders, is supporting this study. The occurrence of adverse events, such as clinical psychological presentation (ie, anxiety, depression) or risk of self-harm and suicide, is considered safety endpoint measures of this trial. Regular contact by support staff will identify whether the safety endpoint measure is required for any participant, and the clinical psychologist on the research team, as per accepted mental health clinical guidelines, would instigate appropriate action.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the University of Sydney human research ethics committee. The committee deemed this study as low risk in terms of ethical issues. The written papers from this study will be submitted for publication in quality peer-reviewed medical and health journals. Study findings will also be disseminated via presentations at local, national and international conferences.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—BG, AC, AK, GL, AH, PM, RC, JH and TB: study concept and design; BG, JB, KVV and NJ: acquisition of data; JB and BG: drafting of the manuscript; BG, AC, AK, GL, AH, PM, JB, KVV, NJ, RC, JH and TB: critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The study is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Partnership Project Grant (APP1115729) and the Macular Disease Foundation Australia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Sydney human research ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1. Foran S, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Causes of visual impairment in two older population cross-sections: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2003;10:215–25. 10.1076/opep.10.4.215.15906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, et al. Lancet 2012;379:1728–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hassell JB, Lamoureux EL, Keeffe JE. Impact of age related macular degeneration on quality of life. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:593–6. 10.1136/bjo.2005.086595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, et al. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116:514–20. 10.1001/archopht.116.4.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bambara JK, Owsley C, Wadley V, et al. Family caregiver social problem-solving abilities and adjustment to caring for a relative with vision loss. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50:1585–92. 10.1167/iovs.08-2744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gopinath B, Liew G, Burlutsky G, et al. And 5-year incidence of impaired activities of daily living. Maturitas 2014;77:263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gopinath B, Kifley A, Cummins R, et al. Predictors of psychological distress in caregivers of older persons with wet age-related macular degeneration. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:1–8. 10.1080/13607863.2014.924477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu C, Kung S, Rummans TA, et al. Reducing caregiver stress with internet-based interventions: a systematic review of open-label and randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gohil R, Crosby-Nwaobi R, Forbes A, et al. Caregiver burden in patients receiving ranibizumab therapy for neovascular age related macular degeneration. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129361 10.1371/journal.pone.0129361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orgül S, Gaspar AZ, Hendrickson P, et al. Comparison of the severity of normal-tension glaucoma in men and women. Ophthalmologica 1994;208:142–4. 10.1159/000310471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Varma R, Tielsch JM, Quigley HA, et al. Race-, age-, gender-, and refractive error-related differences in the normal optic disc. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:1068–76. 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090200074026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Westaway L, Wittich W, Overbury O. Depression and burden in spouses of individuals with sensory impairment. Insight: Research and Practice in Visual Impairment and Blindness 2011;4:29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vukicevic M, Heraghty J, Cummins R, et al. Caregiver perceptions about the impact of caring for patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2016;30 10.1038/eye.2015.235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reinhard SC, Given B, Petlick NH, et al. Supporting family caregivers in providing care Patient safety and quality: an evidence-based handbook for nurses. Hughes RG Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2008:341–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Economics DA. The economic value of informal care in Australia in 2015. 2015. Deloitte Access Economics Pty. Ltd 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Williams K, Owen A. A contribution to research and development in the carer support sector: lessons on effective caring. Family Matters 2009;82:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Craig A, Hancock K, Chang E, et al. The effectiveness of group psychological intervention in enhancing perceptions of control following spinal cord injury. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998;32:112–8. 10.3109/00048679809062717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horrell L, Goldsmith KA, Tylee AT, et al. One-day cognitive-behavioural therapy self-confidence workshops for people with depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2014;204:222–33. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.121855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Craig AR, Hancock K, Dickson H, et al. Long-term psychological outcomes in spinal cord injured persons: results of a controlled trial using cognitive behavior therapy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:33–8. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90006-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, et al. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clin Psychol Rev 2006;26:17–31. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist 2002;42:356–72. 10.1093/geront/42.3.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr 2006;18:577–95. 10.1017/S1041610206003462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brenes GA, Danhauer SC, Lyles MF, et al. Telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy and telephone-delivered nondirective supportive therapy for rural older adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:1012 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kavanagh D, Connolly JM. Mailed treatment to augment primary care for alcohol disorders: a randomised controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009;28:73–80. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mains JA, Scogin FR. The effectiveness of self-administered treatments: a practice-friendly review of the research. J Clin Psychol 2003;59:237–46. 10.1002/jclp.10145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mangione CM, Lee PP, Gutierrez PR, et al. Development of the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:1050–8. 10.1001/archopht.119.7.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Norman R, Cronin P, Viney R. A pilot discrete choice experiment to explore preferences for EQ-5D-5L health states. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11:287–98. 10.1007/s40258-013-0035-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Martin-Carrasco M, Otermin P, Pérez-Camo V, et al. EDUCA study: psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale. Aging Ment Health 2010;14:705–11. 10.1080/13607860903586094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20:649–55. 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale : Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, Measures in health psychology: a user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON, 1995:35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, et al. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.