Abstract

Objective

To examine the development and implementation of a novel income security intervention in primary care.

Design

A retrospective, descriptive chart review of all patients referred to the Income Security Heath Promotion service during the first year of the service (December 2013–December 2014).

Setting

A multisite interdisciplinary primary care organisation in inner city Toronto, Canada, serving over 40 000 patients.

Participants

The study population included 181 patients (53% female, mean age 48 years) who were referred to the Income Security Health Promotion service and engaged in care.

Intervention

The Income Security Health Promotion service consists of a trained health promoter who provides a mixture of expert advice and case management to patients to improve income security. An advisory group, made up of physicians, social workers, a community engagement specialist and a clinical manager, supports the service.

Outcome measures

Sociodemographic information, health status, referral information and encounter details were collected from patient charts.

Results

Encounters focused on helping patients with increasing their income (77.4%), reducing their expenses (58.6%) and improving their financial literacy (26.5%). The health promoter provided an array of services to patients, including assistance with taxes, connecting to community services, budgeting and accessing free services. The service could be improved with more specific goal setting, better links to other members of the healthcare team and implementing routine follow-up with each patient after discharge.

Conclusions

Income Security Health Promotion is a novel service within primary care to assist vulnerable patients with a key social determinant of health. This study is a preliminary look at understanding the functioning of the service. Future research will examine the impact of the Income Security Health Promotion service on income security, financial literacy, engagement with health services and health outcomes.

Keywords: social medicine, public health, primary care, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study of a novel intervention to address poverty directly within a primary care team, which entails having a health promoter focused full time on improving income security.

This study reports on key lessons learnt from implementation, which can inform other interventions focused on social determinants of health.

The generalisability of our findings is limited by the retrospective and descriptive nature of the study and that this was a single-centre study.

This study does not report on the impact of the intervention on specific income or health outcomes, which will be examined by prospective, randomised studies.

Introduction

The social determinants of health are contextual factors and social processes that impact the health of individuals and communities and are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources.1 One of the most important determinants of health is income.2 3 Health outcomes follow a clear income gradient: those with lower incomes have shorter lives and experience a greater burden of disease and disability than individuals with higher incomes. This includes but is not limited to higher rates of cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, stroke and some cancers among people who are living on low incomes.4–8 Living in poverty is also associated with an increased probability of requiring extensive and costly healthcare services later in life.9 10

Income security is defined as a person’s level of income (absolute and relative to needs), level of assurance a person will receive this income and expectation of income adequacy now and in the future.11 12 Interventions to improve income security are typically discussed as policy solutions, including reducing unemployment, raising minimum wage levels and raising social assistance rates.13 However, health providers have become increasingly engaged in discussions about reducing poverty to improve the health of individuals and communities. In Canada, the Ontario Medical Association published a series of articles focused on how physicians can and should address poverty as a health issue.14–16 The Canadian Medical Association has specifically called for the creation of interventions to address poverty within clinical spaces.17 The College of Family Physicians of Canada recently issued a clinical practice guideline for addressing social determinants of health, including through work at the individual level on income security.18

We know that living on a low income is bad for health, but will social interventions to increase income in clinical settings be successful and will they result in better health? Few studies have examined this question directly.19 Exceptions include evaluations of services that are based in general medical practices in the UK that help people living on low income access government benefits.20 21 These services typically involve staff from the Citizen Advice Bureau charity working part time in a general practice and helping patients access government income benefits. A systematic review of such services found a positive impact on income security for patients through improved access to both lump sum and recurring benefits, estimated at £1026 (US$1867, €1498) in the first year after the intervention, based on the 28 studies that reported financial data.22 A single randomised controlled trial of these services found that accessing a Citizen Advice Bureau worker in a general practice led to most participants having an increase in benefits, but no significant health differences at 6 months.23 A recent study of a small, unconditional income supplement provided to low-income pregnant women in Manitoba, Canada, found a reduction in preterm births and low birthweight babies in the intervention group.24 Researchers have hypothesised that improved income security reduces material deprivation and chronic stress, which subsequently improves the physical health of individuals and the social capital of communities.25 26

In Canada, financial advice programmes are occasionally offered by community or social service agencies or rarely through collaboration between a community organisation and a health organisation.27 To our knowledge, there are no clinical services or programmes in a primary care setting in Canada that specifically address income as a determinant of health. Primary care organisations are ideal spaces in which to intervene on social determinants of health and improve health equity.28 29 Primary care is well situated to reach vulnerable patients and to deliver innovative services to improve income.30 Primary care providers may be the first point of contact for people in financial difficulty, usually follow people longitudinally, are increasingly accessible and often have connections to social services.31 Studies to date have focused on understanding barriers to accessing healthcare for those living in poverty,32 barriers to addressing income security in clinical settings or improving access to primary care for marginalised populations as a means for reducing inequities in health,33 but few look at specific programmes or services within primary care that target social determinants of health as potential health equity interventions.30

The Income Security Health Promotion service is a novel intervention to help patients achieve greater income stability through the provision of financial advice and support. Evaluation of this service is a priority as there is a need to study primary care interventions that seek to improve health equity through action on social determinants of health.34–36 In this initial assessment, we conducted a retrospective descriptive chart review of all the patients seen during the first year of the service in order to understand and refine the intervention and also to inform the design of a randomised controlled trial. We report on the patient population, the financial advice and support provided and our lessons learnt from the first year of the service.

Methods

Setting

Ontario’s family health teams (FHTs) are interdisciplinary centres for the delivery of primary care and employ physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, dieticians, pharmacists, social workers and other health professionals.37 The St. Michael’s Hospital Academic FHT serves a panel of over 40 000 patients at six clinics located in downtown Toronto. Over 50% of the patients are estimated to reside in areas with average incomes in the lowest two income quintiles.38 Advancing systems of care for disadvantaged populations is one of the three strategic priorities of St. Michael’s Hospital.39 Physicians within the FHT have engaged in advocacy to address poverty as a health concern, including through helping to establish Health Providers Against Poverty in 200540 and the Ontario College of Family Physicians’ Poverty and Health Committee in 2010.41 Building on this work, physicians in the St. Michael’s Hospital FHT recognised a need for interventions that target poverty in the clinical setting and developed the Income Security Health Promotion service. Provincial funding was obtained from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care for a full-time health promoter to focus on income security and the service launched in December 2013. To our knowledge, it is the first programme of its kind in Canada.

Intervention

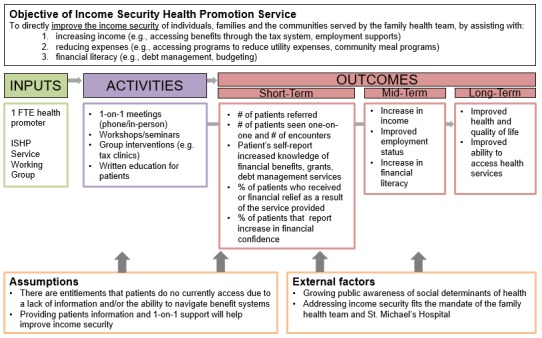

The income security health promoter (ISHP) provides advocacy and case management services that are similar to those of a social worker, but with a specialised knowledge of income support systems and financial issues and a practice dedicated specifically to helping patients with income security. The ISHP is supported by a manager, staff physicians, social workers and a community engagement specialist, who meet biweekly as an advisory group. Patients are referred to the Income Security Health Promotion service by any member of the primary care team, at their discretion. Any individual who could benefit from financial advice and services was eligible for the service. There was no minimum income threshold required for referral, but health professionals are encouraged to use a simple, validated screening question to identify patients living at low income: “Do you have trouble making ends meet at the end of the month?”.42 43 The goal of the Income Security Health Promotion service is to help patients achieve greater income stability through the provision of financial advice and services within three domains: (1) increasing income (eg, accessing benefits through the tax system, employment supports), (2) reducing expenses (eg, accessing rent-geared-to-income housing) and (3) financial literacy (eg, debt management, budgeting). A programme logic model was developed to provide a common framework for understanding how the service will function and what we propose it will accomplish (figure 1). The logic model illustrates the relationships between the service’s inputs, activities and outcome measures and is a tool that guides our overall approach to evaluating the implementation of the service.

Figure 1.

Abbreviated programme logic model for the Income Security Health Promotion service (FTE, full-time equivalent; ISHP, income security health promoter).

Chart review

We conducted a retrospective chart review of the medical records of patients who had engaged with the Income Security Health Promotion service during its first year. Ethics approval was obtained from the St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board. Patients were included in the study if they were referred to the ISHP and their first encounter was between 1 December 2013 and 30 November 2014. Patients were excluded if they were referred to the ISHP but not seen, if their first encounter with the ISHP was outside the study period, or if they had specifically requested that their chart be made private. A search of the electronic medical record (EMR) at the FHT was conducted in March 2015 to identify all patients with any note on their chart to or from the health promoter and then each chart was manually reviewed to identify patients that met the study inclusion criteria.

Data were manually extracted from the EMR, including from the Income Security Health Promotion referral form and the ISHP’s progress notes. The cumulative patient profile was used to collect sociodemographic and general health information: year of birth, gender, three-digit postal code, patient status at the FHT, homelessness, number of problems and number of medications. A patient was considered homeless if they had no fixed address, or if it was indicated that they were living on the street, in a shelter or with friends when they were being seen by the ISHP. As a crude measure of health status, a count of the number of medical problems and the number of medications was performed. In addition to prescription medications, the number of medications also includes items such as vitamins, massage therapy prescriptions and topical creams.

The Income Security Health Promotion referral form was completed by the referring individual and provided the reason for referral, urgency of referral (determined by the referring individual) and current source of income. The referral form could also be used to indicate if there were any barriers to accessing the service.

Most of the ISHP’s notes were entered into the EMR using a standardised encounter form that was completed during patient interactions (in the office or over the phone) and includes information about type and length of appointment, appointment, current income and number of people supported, main problems addressed, action plan and plan for follow-up. This form was not used for brief communications such as short follow-up phone calls or if a patient stopped by to pick up an application form. We analysed all encounters, both those that used this standardised form and those that did not. All data were manually extracted by one author (MKJ) and entered into a chart extraction form.

In addition, we extracted sociodemographic, health and referral information from the charts of individuals who were referred to the service but not seen by the ISHP, to compare this excluded group to our study population.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all measures. Bivariate analyses using t-tests or Pearson’s χ2 statistic, as appropriate, were conducted to compare our study population with the participants who were referred to the ISHP but not seen. Quantitative analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3. Free text notes extracted from the charts were reviewed by two authors (MKJ and ADP). These notes were analysed to identify the key categories of problems that were addressed and to identify the main interventions. We also developed illustrative examples of common cases seen by the ISHP and confirmed their representativeness with the ISHP and the advisory group.

Results

Three hundred and twenty-six charts were identified by the initial EMR search as having been referred to the Income Security Health Promotion service since its inception. Of these, 181 met inclusion criteria for the study. A total of 145 patients were excluded from the study population: 69 patients who were referred to the service but were not seen (eg, did not schedule an appointment or were no-shows) and 76 patients whose first interaction with the service was outside of the study window.

Patient characteristics and referral information are outlined (table 1). All patients were adults, the mean age was 48 years and 53% were female. Approximately 4% of the patients were transgender. The mean number of health problems and medications in the population was 4.7 and 6.4, respectively. A referral form was completed for 66% of the patients (n=119) and about a quarter of referrals were deemed urgent by the referring individual. Examples of urgent referrals made were for individuals who had recently lost their job or income source, or for individuals who were facing eviction or being pursued by creditors. About 20% of referral forms indicated perceived barriers to accessing the service. These barriers included mobility difficulties, mental illness and geographic barriers. There were no significant differences in the demographics or health status between our study population and the individuals who were referred to but not seen by the ISHP. Compared with the study population, individuals who were referred to the service but not seen were more likely to have a referral form completed by the referring provider (p<0.01) and be referred for help with financial literacy (p=0.03).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients referred to the Income Security Health Promotion service

| Seen by the service (n=181) | Referred to the service but not seen (n=69) | |||

| n (%) or mean (95% CI) | n (%) or mean (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | 47.6 (45.4 to 49.8) | 45.8 (41.7 to 50.0) | 0.43 | |

| Gender | Female | 96 (53%) | 34 (49%) | 0.77 |

| Male | 78 (43%) | 33 (48%) | ||

| Transgender* | 7 (4%) | 2 (3%) | ||

| Homeless | 13 (7%) | 7 (10%) | 0.44 | |

| Number of medical problems | 4.7 (4.3 to 5.2) | 5.0 (4.2 to 5.9) | 0.49 | |

| Number of medications | 6.4 (5.7 to 7.2) | 6.1 (4.9 to 7.3) | 0.61 | |

| Referral form present | 119 (66%) | 58 (84%) | <0.01 | |

| Information provided on the referral form | (n=119) | (n=58) | ||

| Source of income† | Hourly wage | 14 (12%) | 12 (21%) | 0.11 |

| Salary | 15 (13%) | 5 (9%) | 0.43 | |

| Social assistance | 55 (46%) | 28 (48%) | 0.80 | |

| Pension | 9 (8%) | 4 (7%) | 0.87 | |

| Workers compensation | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | – | |

| Employment insurance | 9 (7%) | 3 (5%) | – | |

| Other | 26 (22%) | 15 (26%) | 0.55 | |

| Patient needs help with…† | …increasing income | 102 (86%) | 52 (90%) | 0.46 |

| …reducing expenses | 47 (40%) | 29 (50%) | 0.19 | |

| …financial literacy | 36 (30%) | 27 (47%) | 0.03 | |

| Interpreter required | 4 (3%) | 2 (3%) | – | |

| Literacy concerns | 14 (12%) | 7 (12%) | 0.95 | |

| Connected to community resources | 26 (22%) | 11 (19%) | 0.66 | |

| Spends a significant portion of income on medications | 10 (8%) | 8 (14%) | 0.27 | |

| Barriers to accessing health promotion service | 24 (20%) | 13 (22%) | 0.73 | |

| Urgent referral | 31 (26%) | 18 (31%) | 0.49 | |

*Includes male-to-female and female-to male transgender patients; bold face indicates significance at the 95% CI.

†Does not equal 100% because more than one option allowed.

The ISHP interacted with each patient an average of 2.3 times. Most patients interacted with the ISHP once or twice, with fewer patients (16%) requiring four or more appointments to meet their needs. The mean length of time for an encounter was just over an hour (66 min) (table 2). Monthly income information was available for 164 patients, with a mean income of $C1302 per household per month or $C907 per person per month. In terms of the problems addressed, 77% of the encounters dealt with increasing income, most often applying to basic welfare (27%), the Ontario Disability Support Program (36%) or helping a patient with filing taxes (28%). Reducing expenses was addressed in 59% of all encounters, with housing (27%), food (15%) and medications (12%) being the most common areas that required help. In 26% of all encounters, the ISHP addressed financial literacy, which primarily involved discussing budgeting and explaining eligibility for benefits.

Table 2.

Details of patient encounters with the Income Security Health Promotion service

| n (%) or mean (95% CI) | ||

| Length of time for encounter (n=142) | 66 min(61 to 71 min) | |

| Type of encounter (n=181) | One-on-one in office | 130 (71%) |

| Phone assessment | 79 (44%) | |

| One-on-one in community | 6 (3%) | |

| Liaising with community workers | 6 (3%) | |

| Monthly income ($C) (n=164) | $C1301.90 ($C912.95 to $C1690.85) | |

| Number of people supported (n=159) | 1.53 (1.35 to 1.71) | |

| Monthly income per person ($C) (n=144) | $C906.74 ($C744.16 to $C1069.32) | |

| Inappropriate referral to health promoter | 3 (2%) | |

| Main problems addressed in encounter (n=181) | ||

| Increasing income* | Any income problem | 140 (77%) |

| Ontario Works (OW-welfare) | 49 (27%) | |

| Ontario Disability Support Program | 65 (36%) | |

| EI/EI sick benefits | 21 (12%) | |

| Workers Safety Insurance Board | 3 (2%) | |

| CPP/CPP disability | 25 (14%) | |

| Old age security/guaranteed income supplement | 10 (5%) | |

| Child care benefits | 6 (3%) | |

| Loans | 2 (1%) | |

| Gaining employment | 15 (8%) | |

| Education/completion education | 8 (4%) | |

| Training or retraining | 17 (9%) | |

| Filing taxes | 50 (28%) | |

| Disability tax credit | 4 (2%) | |

| Reducing expenses* | Any expense problem | 106 (59%) |

| Housing | 49 (27%) | |

| Medications or medical supplies | 21 (12%) | |

| Transportation | 17 (9%) | |

| Food | 28 (15%) | |

| Clothing | 10 (5%) | |

| Furniture and household supplies | 7 (4%) | |

| Child care | 8 (4%) | |

| Other goods/services | 30 (17%) | |

| Financial literacy* | Any financial literacy problem | 48 (26%) |

| Banking | 12 (7%) | |

| Saving and retirement planning | 11 (6%) | |

| Budgeting | 26 (14%) | |

| Referral for credit counselling | 9 (5%) | |

| Avoiding fraud | 7 (4%) | |

| Bankruptcy | 11 (6%) | |

| Debt restructuring and management | 11 (6%) | |

*Does not sum to 100% as more than one option could be selected.

CPP, Canada Pension Plan; EI, employment insurance.

Most (79%) encounters resulted in the requirement of an action from both the ISHP (79%) and the patient (66%). Approximately 19% were discharged from the service after the first visit and over half (58%) had follow-up planned after the first visit (table 3). An example of a typical case was a man in his 30s with chronic mental illness, who was intermittently receiving basic welfare, had not filed his taxes for several years and had significant debt. The ISHP met with this patient three times and provided information on free tax-filing services and local food banks. She also obtained information from the Canada Revenue Agency to assist with submitting tax documents, provided financial education and counselling on managing his tax refund and referred the patient to legal assistance. Another example of a typical case was a homeless woman in her 60s, who had no income at all when referred and was paying for her medications out-of-pocket. The ISHP met with her six times and assisted with a successful application to Old Age Security and advocated to the pharmacy for a reduction in medication-related costs. A final example was a woman in her 40s who had been dependent on her partner who suddenly passed away. The ISHP met with her six times and assisted with an application for basic welfare, assisted with filing taxes, averted an eviction and helped her access emergency funding for food and clothing.

Table 3.

Action plans developed by the Income Security Health Promotion service

| Action plan details (n=181) | n (%) | |

| Action plan for ISHP* | Any actions required by health promoter | 143 (79%) |

| Provide patient with resources/handouts | 69 (38%) | |

| Consult with external organisation | 60 (33%) | |

| Gather additional information | 45 (25%) | |

| Advocate for patient to external organisation | 48 (26%) | |

| Plan for accompanying patient | 6 (3%) | |

| Form completion/review/assistance | 47 (26%) | |

| Refer internally to family health team | 16 (9%) | |

| Refer externally | 33 (18%) | |

| Other | 14 (8%) | |

| Action plan for patient* | Any action for patient | 119 (66%) |

| Gather supporting documents | 58 (32%) | |

| Contact external organisation | 57 (31%) | |

| Review materials provided | 19 (10%) | |

| Other | 38 (21%) | |

| Plan for follow-up | 105 (58%) | |

| Discharged | 34 (19%) | |

*Does not sum to 100% as more than one option could be selected.

ISHP, income security health promoter.

An example of a poor fit for the service included a woman in her 40s who had severe mental illness, who was referred for assistance with completing a disability application. The ISHP was able to meet with her once and was able to successfully advocate for an extended deadline to submit documents. Her symptoms were so severe that she was unable to attend follow-up appointments or complete even basic documents, resulting in no change in her circumstances. In summary, the ISHP addressed a diversity of financial issues and provided a broad scope of financial advice, financial literacy and interventions to patients.

Discussion

The Income Security Health Promotion service within the St. Michael’s Hospital FHT is a novel primary care intervention to address income as a key social determinant of health. It was developed in response to the call for interventions to address poverty in clinical settings and reduce health inequities in Canada.16 44 Most patients seen were living with multiple health problems and were taking many medications. A large proportion of individuals were receiving social assistance prior to referral, yet still needed help with increasing their income. A number of patients seen were completely destitute (eg, living in a homeless shelter, zero income) and required assistance with obtaining basic necessities. The ISHP’s activities were diverse and included helping individuals access government benefits, file taxes, access affordable housing, develop financial literacy, learn budgeting, plan for retirement and engage in debt restructuring. The ISHP often consulted external organisations, gathered additional information, advocated for the patient to another organisation or helped with form completion for complex benefit programmes. Many patients required help because they faced obstacles to navigating complex health, social and financial systems. Some were newcomers to Canada and faced language barriers, while others were struggling with mental illness that made it difficult to complete forms and follow-up on applications.

A strength of this study was that it included everyone seen by the Income Security Health Promotion service during its first year in operation. Our descriptive analysis should be an accurate representation of the service on the reported measures. Further, we were able to compare our study population with those who were referred to the service but not seen by the ISHP (eg, due to missed appointments or not responding to the ISHP’s messages to set up an appointment). The populations were not significantly different in terms of their sociodemographic factors or health status. The excluded population was more likely to be referred for help with health literacy, however and this may indicate general difficulties with communication that would have been a contributing factor as to why they were not seen by the service.

This study also had limitations. As a retrospective chart review, we were restricted to data contained within patient charts. Patient characteristics that are relevant to understanding the functioning of the programme were not always available, for example, specific disease conditions including presence of mental illness or addictions, family status and employment status. Additionally, the ISHP’s encounter form was designed to capture the main themes rather than the intricacies of appointments. We are unable to estimate the reach of this service in meeting the needs of FHT patients who are living on very low incomes, as we do not have income data from all patients at this time. We were able to capture information on all patients referred and seen during the study period and we detected no significant differences between these groups. However, the small numbers in each category may mean that we lacked the power to detect small but important differences between these groups. Finally, our study is a preliminary descriptive look at the programme and provides a first explanatory insight into the intervention. It does not report on outcomes that measure impact, so it is unknown whether the Income Security Health Promotion service is effective at increasing income or improving health in a primary care setting.

This Income Security Health Promotion service operates in a similar manner to welfare rights advice services that are embedded in general practices in the UK.22 45 46 While the ISHP saw a relatively small proportion of all the patients in the FHT living on very low incomes, the number of patients referred and ultimately seen is comparable to these programmes. Both programmes are similar in their rationales, that income security is an important social determinant of health, patients are usually connected to the service through their health provider and a key goal is to increase access to government benefits.47–49 Key differences are that the ISHP is integrated into the primary care team and has access to the EMR, rather than being an employee of an external organisation. We believe embedding the ISHP into the health team is an important aspect of this service that may improve access, as individuals are already connected with the FHT organisation and may experience reduced stigma for accessing financial advice in this setting, as opposed to accessing financial advice from community-based poverty and income support organisations. Further, the ISHP addresses multiple domains of income security, rather than only government benefits.

The programme also fits within a framework that was developed by Browne et al50 to identify strategies that organisations can use to close the health equity gap. Their framework identifies three distinct levels for which to act: organisational, clinical programming and provider–patient interactions. Many aspects of the Income Security Health Promotion service are aligned with their identified strategies, such as ‘enhancing access to social determinants of health’ and ‘revising use of time’. This service may therefore contribute to reducing health inequities in the communities that are served by the FHT.

A significant portion of the ISHP’s activities involved educating patients. Group education sessions that could reach many patients simultaneously were not conducted during the first year of this programme, but could be a key addition to the service. Many patients required help with filing taxes. Estimates from the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services indicate that social assistance recipients can increase their annual income by 10%–50% through tax filing alone.51 Directing patients to tax clinics, either delivered by the FHT or by community agencies, would likely improve the efficiency of the programme. Some of the ISHP’s work involved connecting patients with easily accessible supports. Other health providers in the FHT could be trained by the ISHP to deliver some basic education, in order to reduce demand on the ISHP.

Based on this study, a number of changes to the implementation of the service are proposed. First, given that a large number of patients were difficult to reach, we recommend asking patients when referred about secondary phone numbers, email addresses and contact information of friends and support workers. We also recommend having the ISHP be colocated directly with clinical services so that particularly hard to reach patients can be introduced to the ISHP at clinical appointments. Second, a few referrals were inappropriate or better served by another service (such as clinical pharmacy or social work). We recommend implementing an initial assessment, perhaps conducted by clerical staff, to ensure the appropriateness of the referral, to identify patient goals and to identify documents required (eg, previous tax returns). This assessment could also include a triage protocol to identify urgent referrals. Third, in order to ensure that patients have been able to address their financial concerns and to assess the impact of the service, we recommend implementing routine follow-up phone calls with patients at 3 months and 6 months after discharge. This may help ensure patients’ action plans are fulfilled. Clearly documenting the impact of the service may assist other team members to understand the service’s impact. Fourth, we recommend instituting a detailed checklist for the ISHP to ensure each patient is made aware of all potential interventions, beyond their immediate goals. Fifth, working with patients one-on-one to address their income security can be difficult for the ISHP in the context of a social system that is unable to meet all needs. Despite the best efforts of such a service, it cannot solve issues like an inadequate supply of affordable housing or insufficient social assistance rates. We recommend that the service incorporate dedicated time for system-level advocacy in collaboration with others.25

Remaining questions that could be explored by further implementation research include examining the experience of patients with the service in both the short-term and medium-term, using qualitative methods. In addition, examining the views and experiences of physicians and other members of the primary care team with the Income Security Health Promotion service would shed light on how well the health promoters are integrated with the rest of the healthcare team and whether there is a substantial link made between addressing biomedical issues and income insecurity. It is highly likely that the effectiveness of the Income Security Health Promotion service is related to the context in which it is operates. Future implementation research could focus on organisational and community contextual factors that enable success or act as barriers. These could include the quality and frequency of communication between ISHP and the healthcare team, organisational support and alignment with mission and the existence and connection to community services that address income security. The effectiveness of the Income Security Health Promotion service could be examined through quantifying the impact on income security and health outcomes in the short-term, medium-term and long-term. A pragmatic randomised controlled trial is planned after changes to the intervention are implemented.

This study is an initial look at the new Income Security Health Promotion service at St. Michael’s Hospital FHT in Toronto, Canada. It is an important step on the pathway to understanding whether addressing low income in the clinical setting is good for health. Our findings may help define the utility of and future directions for this type of novel income security service in primary care settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @AndrewDPinto

Contributors: MKJ assisted with the design of the study, collected the data, analysed it and helped with drafting and editing the manuscript. GB assisted with the design of the study and preparation of the manuscript. ADP led the design of the study, assisted with the collection and analysis of data and helped with drafting and editing the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported in part by the TD Financial Literacy Grant Fund. Dr. Andrew D. Pinto is supported by the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto; the Department of Family and Community Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital; and the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board (14-415).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: what we know and what we don’t. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:3–15. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Public Health Agency of Canada. What makes Canadians healthy or Unhealthy? Population Health Approach Public Health Agency of Canada. 2013. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/determinants/determinants-eng.php#education.

- 4. Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on The State of Public Health in Canada 2008. 2008. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cphorsphc-respcacsp/2008/fr-rc/cphorsphc-respcacsp05a-eng.php.

- 5. Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Do socioeconomic differences in mortality persist after retirement? 25 year follow up of civil servants from the first Whitehall study. BMJ 1996;313:1177–80. 10.1136/bmj.313.7066.1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ 2001;322:1233–6. 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marmot M. Why should the rich care about the health of the poor? CMAJ 2012;184:1231–2. 10.1503/cmaj.121088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social Determinants of Health: the solid facts. World Heal Organ 2003;2:1–33. 10.1016/j.jana.2012.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fitzpatrick T, Rosella LC, Calzavara A, et al. . Looking Beyond Income and Education. Am J Prev Med 2015:1–11. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosella LC, Fitzpatrick T, Wodchis WP, et al. . High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:532 10.1186/s12913-014-0532-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. International Labour Organization. Income security index. http://www.ilo.org/sesame/SESHELP.NoteISI (accessed 3 Jun 2017).

- 12. International Labour Organization. Economic security for a better world. Geneva, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manzano AT, Raphael D. CPHA and the social determinants of health: an analysis of policy documents and statements and recommendations for future action. Can J Public Health 2010;101:399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bloch G, Etches V, Gardner C, et al. . Why poverty makes Us sick: a physician backgrounder. Ont Med Rev 2008:32–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bloch G, Etches V, Gardner C, et al. . Identifying poverty in your practice and community. Ont Med Rev 2008:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bloch G, Etches V, Gardner C, et al. . Strategies for physicians to mitigate the health effects of poverty. Ont Med Rev 2008:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health care transformation in canada. Physicians and health equity: opportunities in practice. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. The College of Family Physicians of Canada. Best Advise:Social Determinants of Health. 2015. http://patientsmedicalhome.ca/resources/best-advice-guide-social-determinants-health/.

- 19. Kiran T, Pinto AD. Swimming ‘upstream’ to tackle the social determinants of health. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:138–40. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paris JA, Player D. Citizens’ advice in general practice. BMJ 1993;306:1518–20. 10.1136/bmj.306.6891.1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abbott S, Hobby L, Cotter S. What is the impact on individual health of services in general practice settings which offer welfare benefits advice? Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:1–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adams J, White M, Moffatt S, et al. . A systematic review of the health, social and financial impacts of welfare rights advice delivered in healthcare settings. BMC Public Health 2006;6:81 10.1186/1471-2458-6-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mackintosh J, White M, Howel D, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of welfare rights advice accessed via primary health care: pilot study (ISRCTN61522618). BMC Public Health 2006;6:162 10.1186/1471-2458-6-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brownell MD, Chartier MJ, Nickel NC, et al. . Unconditional prenatal income supplement and birth outcomes. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20152992 10.1542/peds.2015-2992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abbott S. Prescribing welfare benefits advice in primary care: is it a health intervention, and if so, what sort? J Public Health Med 2002;24:307–12. 10.1093/pubmed/24.4.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Allmark P, Baxter S, Goyder E, et al. . Assessing the health benefits of advice services: using research evidence and logic model methods to explore complex pathways. Health Soc Care Community 2013;21:59–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01087.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shartal S, Cowan L, Khandor E, et al. . Failing the Homeless: barriers in the Ontario Disability support program for homeless people with Disabilities. Toronto, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Starfield B. Toward international primary care reform. CMAJ 2009;180:1091–2. 10.1503/cmaj.090542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Starfield B. Primary Care and Equity in Health: The Importance to Effectiveness and Equity of Responsiveness to Peoples’ Needs. Humanity Soc 2009;33:56–73. 10.1177/016059760903300105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shadmi E, Wong WC, Kinder K, et al. . Primary care priorities in addressing health equity: summary of the WONCA 2013 health equity workshop. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:104 10.1186/s12939-014-0104-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maeseneer J, Willems S, De Sutter A, et al. . Primary health care as a strategy for achieving equitable care: a literature review commissioned by the Health Systems Knowledge Network. 2007. www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/csdh_media/primary_health_care_2007_en.pdf.

- 32. Loignon C, Hudon C, Goulet É, et al. . Perceived barriers to healthcare for persons living in poverty in Quebec, Canada: the EQUIhealThY project. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:4 10.1186/s12939-015-0135-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bloch G, Rozmovits L, Giambrone B. Barriers to primary care responsiveness to poverty as a risk factor for health. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:62 10.1186/1471-2296-12-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tatsioni A, Lionis C. Responding to financial and economic crisis: what methodology and interventions we need in family practice research. Fam Pract 2016;33:1–3. 10.1093/fampra/cmv105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loignon C, Fortin M, Bedos C, et al. . Providing care to vulnerable populations: a qualitative study among GPs working in deprived areas in Montreal, Canada. Fam Pract 2015;32:232–6. 10.1093/fampra/cmu094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruano AL, Furler J, Shi L. Interventions in Primary Care and their contributions to improving equity in health. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:153 10.1186/s12939-015-0284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Glazier RH, Kopp A, Schultz SE, et al. . All the right intentions but few of the desired results: lessons on access to primary care from Ontario’s patient enrolment models. Healthc Q 2012;15:17–21. 10.12927/hcq.2013.23041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murphy K, Glazier R, Wang X, et al. . Hospital Care for all: an Equity Report on differences in Household Income among patients at Toronto Central Local Health integration Network (TC LHIN) Hospitals, 2008-2010. 2012. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2012/Hospital-Care-For-All (accessed 31 May 2017).

- 39. St. Michael’s Hospital. St. Michael’s Hospital Strategic Plan 2015-18: World Leadership in Urban Health. Toronto, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poverty HPA. Health Providers against Poverty. https://healthprovidersagainstpoverty.ca/ (accessed 2 Jun 2017).

- 41. Ontario College of Family Physicians. Primary care interventions in poverty. 2016. http://ocfp.on.ca/cpd/povertytool (accessed 7 Nov 2016).

- 42. Brcic V, Eberdt C, Kaczorowski J. Development of a Tool to Identify Poverty in a Family Practice Setting: A Pilot Study. Int J Family Med 2011;2011:1–7. 10.1155/2011/812182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brcic V, Eberdt C, Kaczorowski J. Corrigendum to ?Development of a Tool to Identify Poverty in a Family Practice Setting: A Pilot Study? Int J Family Med 2015;2015:1 10.1155/2015/418125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Best advice - Social determinants of health. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Abbott S, Hobby L. Welfare benefits advice in primary care: evidence of improvements in health. Public Health 2000;114:324–7. 10.1016/S0033-3506(00)00356-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moffatt S, Mackintosh J. Older people’s experience of proactive welfare rights advice: qualitative study of a South Asian community. Ethn Health 2009;14:5–25. 10.1080/13557850802056455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greasley P, Small N. Providing welfare advice in general practice: referrals, issues and outcomes. Health Soc Care Community 2005;13:249–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levy J. Welfare Rights Advocacy in a Specialist Health and Social Care Setting: A Service Audit. Br J Soc Work 2006;36:323–31. 10.1093/bjsw/bch366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moffatt S, Noble E, White M. Addressing the financial consequences of cancer: qualitative evaluation of a welfare rights advice service. PLoS One 2012;7:e42979 10.1371/journal.pone.0042979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Browne AJ, Varcoe CM, Wong ST, et al. . Closing the health equity gap: evidence-based strategies for primary health care organizations. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:59 10.1186/1475-9276-11-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ministry of Community and Social Services, Government of Ontario. The role of refundable tax credits. Toronto, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.