Abstract

The intrinsic nature of glycosylation, namely nontemplate encoded, stepwise elongation and termination with a diverse range of isomeric glyco-epitopes (glycotopes), translates into ambiguity in most cases of mass spectrometry (MS)-based glycomic mapping. It is arguable that whether one needs to delineate every single glycomic entity, which may be counterproductive. Instead, one should focus on identifying as many structural features as possible that would collectively define the glycomic characteristics of a cell or tissue, and how these may change in response to self-programmed development, immuno-activation, and malignant transformation. We have been pursuing this line of analytical strategy that homes in on identifying the terminal sulfo-, sialyl, and/or fucosylated glycotopes by comprehensive nanoLC-MS2-product dependent MS3 analysis of permethylated glycans, in conjunction with development of a data mining computational tool, GlyPick, to enable an automated, high throughput, semi-quantitative glycotope-centric glycomic mapping amenable to even nonexperts. We demonstrate in this work that diagnostic MS2 ions can be relied on to inform the presence of specific glycotopes, whereas their possible isomeric identities can be resolved at MS3 level. Both MS2 and associated MS3 data can be acquired exhaustively and processed automatically by GlyPick. The high acquisition speed, resolution, and mass accuracy afforded by top-notch Orbitrap Fusion MS system now allow a sensible spectral count and/or summed ion intensity-based glycome-wide glycotope quantification. We report here the technical aspects, reproducibility and optimization of such an analytical approach that uses the same acidic reverse phase C18 nanoLC conditions fully compatible with proteomic analysis to allow rapid hassle-free switching. We further show how this workflow is particularly effective when applied to larger, multiply sialylated and fucosylated N-glycans derived from mouse brain. The complexity of their terminal glycotopes including variants of fucosylated and disialylated type 1 and 2 chains would otherwise not be adequately delineated by any conventional LC-MS/MS analysis.

One of the most conspicuous hallmarks of protein glycosylation is its extreme structural heterogeneity driven by nontemplate encoded stepwise elongation and branching from a few invariant core structures (1). Terminal or peripheral sialylation, fucosylation and/or sulfation then generate a plethora of terminal glyco-epitopes, or glycotopes, distributed over myriad carrier glycans and proteins. MS-based glycomics (2, 3), despite being highly sensitive in affording high precision mass measurement at high throughput, often fails to reveal the least abundant glycotopes. A glycotope can be a very minor constituent of the glycome and yet be highly relevant when carried and presented properly at specific sites of receptors. Any change in abundance or additional modifications imparted on this glycotope may well be undetectable at the glycomic level and yet will have profound impact on the functions of its carriers. This calls into question if current glycomics is of sufficient analytical depth to address the most relevant glycobiology issues. Indeed, there is a considerable gap among positive detection of a glycotope by monoclonal antibody or lectin, and its identification by MS. Although the most notable pitfalls of probing by antibody are its poorly defined cross-reactivity and not informative of carrier glycans, that of MS is a need to further resolve the isomeric or isobaric constituents of a glycotope defined by a unique mass.

There will always be practical limitations in resolving each of the structural and stereoisomeric glycans chromatographically, particularly as the glycan size gets bigger along with increasing permutation of isomeric arrangements. MS2 and often MS3, if not higher orders, are needed to define linkage and substituent positions (4, 5). In that respect, the most reliable MS-based glycan sequencing is based not on analyzing native but permethylated glycans (5, 6). In fact, the advantages of permethylation extend beyond that. We have previously shown that by converting all hydroxyl groups including the carboxylic groups of sialic acids into O-methyl, permethylation allows simple enrichment and identification of a wealth of sulfated glycans occurring at low abundance that would otherwise not be detected (7, 8). We further demonstrated that negative ion mode nanoLC-MS/MS can be productively applied in acidic buffer commonly used in proteomics without compromising much the stability and detection sensitivity (9). Low mass MS2 diagnostic ions for locating the sulfate onto the common Galβ1–3/4GlcNAc unit, with and without additional sialylation, were identified and we suggested that ambiguity in assignment can conceivably be addressed by additional MS3 mode that will not suffer from low mass cutoff the way an ion trap based fragmentation would (9).

The advent of new generations of Orbitrap series with increasing data acquisition speed and flexibility in combining multiple stages of higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) with ion trap collision induced dissociation (CID)1, invites innovative multimode MS2/MS3 data acquisition and processing methods that would best address the most relevant glycomic features. An important concept to be advanced here is that any structural feature that can be defined by diagnostic ions at MS2 and/or MS3 level can thus be identified and relatively quantified based on its MS2/MS3 ion intensity and the frequency it was produced in an automated LC-MS2/MS3 analysis. We have experimented with a glycotope-centric glycomic workflow, which aims foremost to delineate the various isomeric glycotopes by well-established diagnostic ions. Using the same acidic solvent system for both positive and negative ion mode data acquisition allows for rapid switching within or in between runs to probe for occurrence of target (sulfo)-glycotopes and to derive quantification indices for rapid comparison across as many biological sources. This allows us to ask how these sialylated, fucosylated and/or sulfated glycotopes were affected on pathophysiological activation, and/or genetically or chemically manipulated in vivo and in vitro, in a way never possible. Aided by our own in-house developed data mining tool, tens of thousands of MS2/MS3 spectra can now be meaningfully interrogated by nonexperts and relevant glycotope information extracted in a fully automated fashion to make glycomics more commonplace.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Enzymes, and Reagents

Both Colo205, a human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line, and AGS, a human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line, were purchased from Bioresource Collection and Research Center (Hsinchu, Taiwan). Colo205 was cultured in 90% RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technology, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and AGS was cultured in 90% Ham's F-12 nutrient mix (Life Technology) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific). Fucosylated glycan standards, including Lewis A hexaose (GLY055), Lewis X hexaose (GLY051), H antigen pentaose type 1, (GLY033–1), H antigen pentaose type 2, (GLY033–2), Lewis B pentaose (GLY056), Lewis Y pentaose (GLY052), and Sialyl Lewis X Pentaose (GLY053), were purchased from Elicityl OligoTech, Crolles, France.

Mouse Striatum Tissues

Male C57BL/6J (8–12 weeks old) were bred and maintained in the animal core of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences at Academia Sinica following the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Academia Sinica. Brain striatum tissues were carefully removed, minced into small pieces, and transferred into a 2-ml grinder and homogenize on ice using a homogenization buffer (1 mm EGTA, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 nm okadaic acid, 100 μm, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 40 μm leupeptin, 25 mm Tris HCl buffer, pH8.0) containing the 1X cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor (Roche, Switzerland), and 1× phosStop (Roche, Switzerland). The homogenate was first centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove debris. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 50,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to collect membrane fractions existing in the pellets. Pellets were suspended with an ice-cold lysis buffer (0.2 mm EGTA, 0.2 mm MgCl2, 30 nm okadaic acid, 40 μm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mm leupeptin, 0.2 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 20 mm HEPES, pH 8.0 plus 1X cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor and 1X phosStop) and stored at −80 °C until used.

Glycan Release and Permethylation

Harvested 1 × 107 AGS, Colo205 cells and membrane fraction from one mouse striatum were extracted by lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. The supernatants were subjected to reduction by 10 mm DTT at 37 °C for 1 h, alkylation by 50 mm iodoacetamide at 37 °C for 1 h in the dark, and then precipitation by TCA to a final concentration of 10%. The remaining detergents were further removed by cold acetone precipitation and the recovered proteins were digested overnight by trypsin (250 μg for cells or 50 μg for extracts from 1 mouse striatum) in 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate at 37 °C, followed by same amount of chymotrypsin in the same buffer at 37 °C for 6 h. N-glycans were released by 3 U of PNGase F treatment and O-glycans by alkaline β-elimination from the de-N-glycosylated glycopeptide, as described (7). Both the released N- and O-glycans were permethylated by the sodium hydroxide/DMSO slurry methods (8) at 4 °C for 3 h and separated into nonsulfated, monosulfated, and the multiply sulfated glycans by loading the neutralized reaction mixtures onto a primed Oasis® Max solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) (10), and eluted off by 95% acetonitrile, 1 mm ammonium acetate in 80% acetonitrile, and 100 mm ammonium acetate in 60% acetonitrile/20% methanol, respectively. Before MS analysis, aliquots from all fractions were additionally cleaned up by applying to ZipTip C18 in 0.1% formic acid and eluted by 75% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid. The permethylated glycan standards and samples were dissolved in 10 μl of 10% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid.

NanoLC-MS/MS Systems

An UltiMateTM 3000 RSLC nano system (ThermoFisher Scientific) was interfaced to an Orbitrap Fusion™ Tribrid™ Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) via a PicoView nanosprayer (New Objective, Woburn, MA) for nanoLC separation at 50 °C using a 25 cm x 75 μm C18 column (Acclaim PepMap® RSLC, ThermoFisher Scientific) at a constant flow rate of 500 nL/min. The solvent system used were 100% H2O with 0.1% formic acid (FA) for mobile phase A, and 100% ACN with 0.1% FA for mobile phase B. A 60 min linear gradient of 25 to 60% B for O-glycan, and 30 to 80% B for N-glycan and mono-sulfated O-glycan, was used for eluting the permethylated glycans. Another EASY-nLC™ 1200 system was interfaced to an Orbitrap Fusion™ Lumos™ Tribrid™ Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) via a Nanospray Flex™ Ion Sources (ThermoFisher Scientific) for nanoLC separation at 50 °C using the same 25 cm x 75 μm C18 column (Acclaim PepMap® RSLC, ThermoFisher Scientific) at a constant flow rate of 300 nL/min. The solvent system used were 100% H2O with 0.1% FA for mobile phase A and 80% ACN with 0.1% FA for mobile phase B. A linear gradient of 40 to 95% B in 70 min was used for analysis of the permethylated mono-sulfated O-glycan.

The Orbitrap Fusion™ Tribrid™ mass spectrometer was operated in positive mode for analyses of nonsulfated N-glycans (m/z mass range 800–2000, charge state 2 to 4) and O-glycans (m/z mass range 500–1700, charge state 1 to 3). Top speed mode was used for data dependent acquisition at 3 s duty cycle. Full-scan MS spectrum was acquired in the Orbitrap at 120,000 resolution with automatic gain control (AGC) target value of 4 × 105, followed by quadrupole isolation of precursors at 2 Th width for higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD)-MS2 at 15% normalized collision energy (NCE) ± 5% stepped collision, with 10 s dynamic exclusion applied. HCD MS2 fragment ions were detected in the Orbitrap analyzer at 30,000 resolution at an AGC target value of 5 × 104. Target HCD-MS2 ions detected at high resolution and accurate mass (HR/AM) within 10 ppm were selected automatically for product-dependent MS3 (pd-MS3) acquisition in the ion trap using CID at an AGC target value of 1 × 104 and 30% NCE, followed by ion trap detection. The MS system was operated in negative ion mode for analyses of mono-sulfated O-glycans (m/z mass range 700–2000, charge state 1). The same Orbitrap resolution and AGC target value were applied for MS1 but a 5 s top speed mode was used instead for parallel HCD/CID MS2 data dependent acquisition (9). The AGC target value and NCE for CID MS2 in the ion trap was set at 1 × 104 and 40%, respectively. For HCD MS2 to be detected in the Orbitrap analyzer at 30,000 resolution, the AGC target values was set at 5 × 104 and NCE at 50% with ± 10% stepped collision energy. For additional pd-HCD MS3 data acquisition, the AGC target value and NCE were set at 1 × 104 and 45%, respectively. All data were processed by in-house developed software GlyPick v1.0 and Xcalibur software v2.2.

GlyPick Software Development

GlyPick was developed using Microsoft Visual Studio 2013 professional edition in conjunction with Thermo Raw API (Version 3.0 sp3) for data extraction from Thermo raw file. Its parameter settings can be fine-tuned by user inputs via a graphic user interface (GUI) according to the specific data set to be analyzed, and output along with the result files. GlyPick starts from picking out only those MS2 spectra containing at least 1 or 2 user-specified glycan fragment MS2 ions and then tracks each of the selected MS2 scan back to its preceding MS1 scan and associated pd-MS3 scans. The m/z value of the monoisotopic precursor will then be determined from accurately mass measured MS1 scan and listed alongside that of the triggered precursor, its peak intensity, elution time and scan numbers. The generated output file in Excel format also tabulates as many of the user-defined MS2 ions detected above specified intensity threshold and within the mass accuracy tolerance, along with the signal intensities of each. For pd-MS3 scans, predefined diagnostic MS3 ions, if detected, will be used to identify specific glycotope in addition to a listing of all detected MS3 ions and their signal intensities. The total number of spectra in which each of the specified MS2 and MS3 ions diagnostic of particular glycosylation features or glycotopes was detected will be counted and their respective intensities summed for the purpose of relative quantification. Because multiple pd-MS3 events (normally ≥ 3) were specified, as many MS2 events were actually triggered for the same MS1 precursor to isolate the respective MS2 ion for each pd-MS3 without acquiring the additional MS2 data. For quantification purpose based on spectral counting and summing of ion intensity, the MS1 and MS2 scans were each duplicated for every additional pd-MS3 scans to compensate for the time spent on the same precursor. This extrapolation may end up giving extra quantification weighting for MS2 scans containing more MS2 ions targeted for pd-MS3 but deemed justifiable and give a better approximation for the glycotope-centric analysis.

GlyPick can also mass fit the m/z values of identified monoisotopic precursors to glycosyl compositions, with or without considering additional user-defined adducts, modifications, maximum and minimum number of allowed glycosyl residues, and simple rules of permissible combination derived from biosynthetic constrains. Either a single round or iterative rounds of fitting can be executed. The latter involves initial fitting without considering the extra permutations generated by cation adducts and under-methylation. MS2 scans fitted will then be removed and the remaining be fitted again by considering the extras. All monoisotopic precursors thus assigned to the same glycosyl composition can be optionally grouped and their inferred MS1 peak intensities summed to provide a quantitative measure of relative abundance.

GlyPick version 1.0 containing all features described in this work is available on request for testing while new features are being added and performance continuously optimized.

Identification of Glycotopes and Reported Glycan Structures

All glycotopes reported were based on detecting their respective MS2 and MS3 ions, as extracted out from the MS/MS data set by GlyPick. The critical glycosyl linkages for discriminating the various fucosylated glycotopes and location of sulfates can thus be unambiguously defined but the Gal/GlcNAc identification was inferred directly from Hex/HexNAc without further verification. The anomeric configuration was likewise based on presumptive glycobiology knowledge and not further defined. MS1 precursors fitted with glycosyl compositions by GlyPick were not meant to imply glycan structural identification. Only select glycans with their MS/MS spectra manually interpreted and shown annotated with cartoon drawings are considered as structurally assigned to be singled out for discussion. Their monosaccharide stereochemistry and anomeric configurations were similarly not further verified.

RESULTS

Most of the current offline nanospray MS/MS or online nanoLC-MS/MS analysis of permethylated glycans were conducted in positive ion mode doped with sodium to promote sodiated molecular ions (11–13), which would afford more complete sets of fragment ions. In contrast, under acidic conditions, the protonated molecular ions would mostly yield highly abundant nonreducing terminal oxonium ions via cleavage at HexNAc, concomitant with characteristic elimination of substituents at its C3 position (14, 15). The advantages offered are two folds: (1) fully compatible with conventional proteomic data acquisition workflow to allow convenient scheduling, because there is no need to change solvent and nanoLC set-up, with no unwarranted introduction of sodium into sophisticated high-end MS instrument system; (2) abundant MS2 product ion to be selected for MS3, with reliable, characteristic MS3 ions informative of the linkage. The programmed data acquisition mode is called product-dependent (pd)-MS3, which would automatically isolate any of the targeted MS2 ions for further stage of HCD/CID fragmentation. As demonstrated against a panel of authentic standards (supplemental Fig. S1), each of the fucosylated glycotopes can thus be unambiguously defined based on which glycosyl residue is eliminated from the C3-position of the GlcNAc+.

Characteristic Features of RP nanoLC-MS/MS of Permethylated Glycans

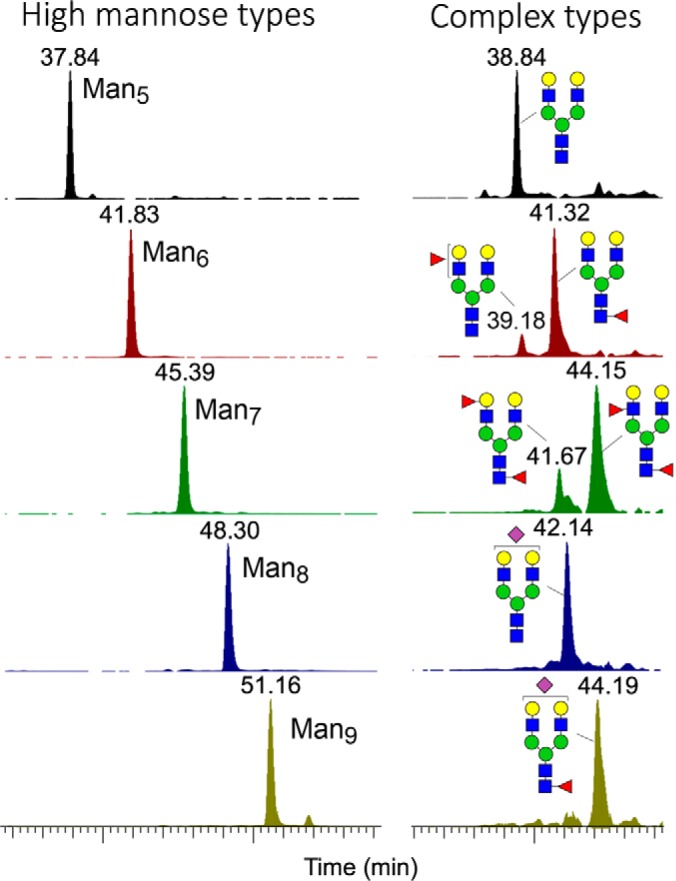

For the smaller O-glycans, the RP C18 nanoLC-separation afforded at elevated temperature is reasonably satisfactory. To take a simple case example, the O-glycan with a Fuc1Hex2HexNAc2-itol composition from AGS cells was found to comprise both simple core 2 and extended core 1 structures with Fuc on either Gal or GlcNAc giving rise to H or LeX, respectively. These were resolved into at least 4 distinct major peaks, with structures carrying H eluting earlier than LeX, and the branched core 2 earlier than extended core 1 (Fig. 1). Additional structural isomers carrying LeA would elute slightly later than the LeX counterparts as demonstrated with similarly prepared and analyzed O-glycan sample from colo205 cells. This is further corroborated by the elution order of type 1 versus type 2 chain carried on a nonfucosylated extended core 1 structure. A label free quantification based on extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) of the resolved peaks for these smaller O-glycans including Tn, sialyl Tn and T is thus possible (supplemental Fig. S2). However, as the size increases, so are the possible structural isomers, concomitant with the increase in the number of nonfully resolved peaks for each XIC. Similar pattern also extends to sulfated O-glycans analyzed in negative ion mode, as described previously (supplemental Fig. S2, S3) (9). For the N-glycans, each of the Man5–9GlcNAc2 can be clearly separated but not the individual isomers, whereas multiantennary complex type structures with various degrees of fucosylation and sialylation were not efficiently resolved (Fig. 2) (16). Nevertheless, the terminal fucosylated epitopes as detected by MS2 could be similarly targeted for MS3 to define the occurrence of Lewis versus H glycotopes.

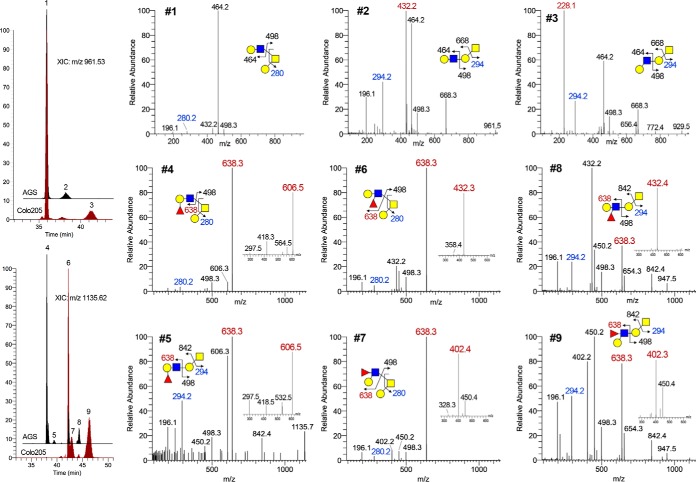

Fig. 1.

RP C18 nanoLC separation and MS2/MS3 identification of permethylated, nonfucosylated and mono-fucosylated, single LacNAc-extended core 1 and core 2 O-glycan structures. Overlay plots of extracted ion chromatograms for the nonfucosylated (m/z 961.53) and monofucosylated (m/z 1135.62) (Hex-HexNAc)-Hex-HexNAcitol derived from AGC and Colo205 cells are shown to demonstrate ability to resolve the smaller isomeric O-glycans. Peaks are labeled #1 - 9, the MS2 and target MS3 (small inset) spectra of which are shown in 9 small panels, with the diagnostic oxonium ions annotated in red. Z1 ion for the reducing end GalNAitol (annotated in blue) could be readily detected at m/z 294 or after further loss of 6-arm substituents at m/z 280, which is informative of core 1 versus core 2 structures. A Z2 ion at m/z 498 is also commonly observed for all core structures that are extended at either the 6 or 3-arm but not both. Extended core 1 structure further afforded a B ion at the Gal of the Gal-GalNAcitol, e.g. m/z 668 and 842, which is very useful to define the entire moiety extending from the 3-arm. Under low collision energy, protonated permethylated glycans do not normally yield cross-ring cleavage ions.

Fig. 2.

RP C18 nanoLC separation of permethylated high mannose type and biantennary complex type N-glycans. Overlay plots of extracted ion chromatograms for the high mannose structures indicated that the Man5–9GlcNAc2itol N-glycans were well resolved from one another but not for their individual isomeric constituents. Larger complex type N-glycans, with and without sulfates, produced more complicated and not well resolved ion chromatograms, the unambiguous identification of individual chromatographic peaks based on MS2 of the protonated molecular ions alone is not feasible but glycotopes carried on each can still be efficiently determined by MS2-pd-MS3 analysis.

Typically with our Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid instrument settings and acquisition parameters, a duty cycle of 3 s (Top Speed mode) applied to a sample of relatively high complexity could fit in an average total of 25 MS2+MS3 scans for a positive mode nanoLC-HCD-MS2-pd-CID-MS3 analysis, with the MS1 and HCD-MS2 scan being mass measured in the Orbitrap at 120 K and 30 K resolution, respectively. This amounts to an average total of > 20,000 MS2/MS3 spectra acquired within the effective elution range of glycans. In negative ion mode for the sulfated glycans, we opted instead for nanoLC-parallel CID/HCD-MS2-pd-HCD-MS3 at a duty cycle of 5 s. Both CID and HCD MS2 were similarly mass detected in the Orbitrap for high resolution and mass accuracy but the HCD-MS3 spectra were acquired in the ion trap after fragmentation in the HCD cell to increase sensitivity. A typical run also produced an average total of MS2+MS3 scans like that in positive ion mode for nonsulfated glycans. As with all proteomics and glycoproteomics data, the sheer number of spectra defies laborious manual interrogation and expert interpretation. To facilitate the data mining and analysis process, we have developed a computational tool named GlyPick, which aims to automate the data analysis process for nonexperts.

Identification and Relative Quantification of Target Glycotopes by GlyPick

GlyPick implements different levels of data mining starting from MS2 data. At the first level, the raw data will be processed and nonglycan and/or poor quality MS2 data will be filtered away. This step relies on high resolution/accurate mass MS2 data and the choice of diagnostic glycan ions that can be input by user (supplemental Fig. S4 for GUI), with options available for specifying at least how many of these common glycan MS2 ions must be detected at 5 ppm or less above a predefined intensity threshold for a spectrum to qualify as bona fide glycan MS2 spectrum. The advantage of analyzing protonated molecular ions is obvious here because the oxonium ions corresponding to terminal glycotopes including simple NeuAc+, HexNAc+ and Hex-HexNAc+ are usually abundant. By tracking the preceding MS1 survey scan, GlyPick will attempt to determine the correct monoisotopic precursor and all relevant information will be collated, which includes (1) the scan number (and elution time) for MS1, MS2 and associated MS3 if triggered; (2) the peak intensity for the precursor and each of the characteristic MS2 and MS3 ions; (3) the m/z for inferred monoisotopic peak versus experimentally triggered precursor, and the value of z.

As first proposed and implemented in proteomics, the spectral count or its equivalents can be taken as a rough indication of abundance (17, 18). In our case, the number of times a unique glycan precursor defined by its mass is selected for MS2 can conceivably be used to indicate its relative abundance under nonsaturating conditions. However, this level of counting is less useful for glycomics because each precursor often comprises many different isomers and many different glycans share the same glycotopes. To map the glycomic occurrence and relative abundance of a glycotope, we have resorted instead to count the number of glycan MS2 spectra in which a diagnostic MS2 ion is detected and to sum its peak intensity. For isomeric glycotopes that can only be resolved at MS3 level, we further sum the intensity of each diagnostic MS3 ion detected in all productive MS3 spectra for a given target glycotope. This novel idea of identifying and relative quantification of target glycotopes at glycomic level was first tested out using the nonsulfated AGS O-glycan sample as a case study (Fig. 3). To ascertain reproducibility from essentially a random data dependent acquisition (DDA) sampling event, we have varied the concentration of injected analytes across 10× dilution range (supplemental Table S1) and additionally performed a technical triplicate analyses for the 4-fold diluted O-glycan sample (supplemental Table S2).

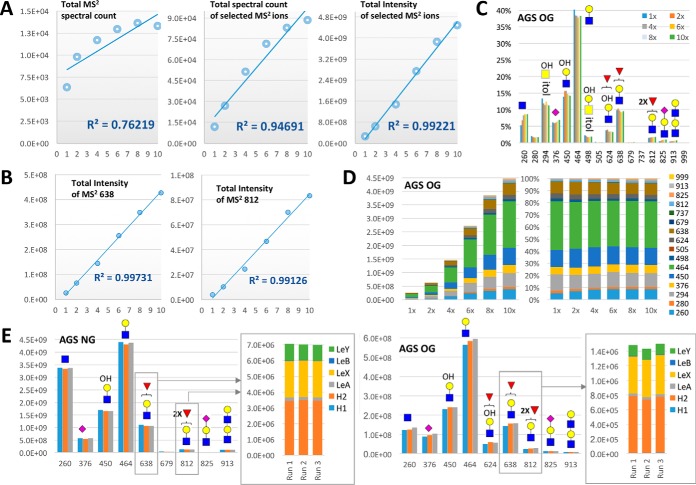

Fig. 3.

Identification of terminal glycotopes and their relative quantification based on diagnostic MS2/MS3 ions. A, Similar nanoLC-MS2-pd-MS3 analyses of permethylated AGS O-glycans over 10 fold difference in injected sample amount demonstrated that the sum of all selected MS2 ion intensity (right panel) is a better indicator of the relative abundance of total glycans than the total number of MS2 spectra acquired (spectral count) that contained at least 2 of the selected diagnostic ions, with (middle panel) or without (left panel) redundant counting of a particular spectrum as many times as the number of selected ions it contained. B, At the individual MS2 ion level, the sum total of its ion intensity showed a linearity across 10x difference in sample amount, shown here for m/z 638 and 812 (see supplemental Fig. S5 for a complete chart of all selected MS2 and MS3 ions). C, A plot of the summed individual MS2 ion intensity calculated as a % total of the summed ion intensities for all selected MS2 ions demonstrated a good reproducibility across the 10x concentration range analyzed. D, The individual amount of each detected glycotope as represented by the summed ion intensity of its corresponding MS2 ions increased proportionally over the 6 different concentrations analyzed, as shown by the stacked column chart (left panel). The relative amount of these constituent glycotopes expressed as % total in the 100% stacked column chart (right panel) stays remarkably consistent across the 10x concentration range despite the inherently stochastic nature of MS2 data acquisition. E, Good reproducibility was also obtained on triplicate profiling of the terminal glycotopes based on summing the total ion intensities of each of the selected MS2 ions. For the mono- and difucosylated Gal-GlcNAc glycotopes represented by MS2 ions at m/z 638 and 812 respectively, analogous summing of the diagnostic MS3 ion intensities (see supplemental Fig. S5) allows a reproducible mean to delineate its isomeric constituents for comparison across different samples. Full experimental data set used to generate the various charts here and supplemental S5 can be found in supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

As expected, a better linearity over 10x concentration was observed when the ion intensity and not just the spectral count for all the selected MS2 ions was totaled (Fig 3A). This indicated that for normalization purpose, the sum of all selected MS2 ions, either by count or intensity, is a better indicator of the total glycan amount injected than the total nonredundant MS2 spectral count itself, within the loading capacity defined by the C18 Zip-Tip used for pre-LC-MS/MS clean-up. For the nondiluted sample, a total of over 13,000 MS2 scans containing at least 2 glycan-specific MS2 ion detected within 5 ppm (out of 16 input for data mining by GlyPick) were acquired within the effective nanoLC time range of 20 to 70 min. The common MS2 oxonium ions such as m/z 260, 450, 464, and 638, representing terminal HexNAc+, (HO)1Hex1HexNAc+, Hex1HexNAc+, and Fuc1Hex1HexNAc+, respectively, were each detected in > 10,000 MS2 spectra, whereas a few ions such as m/z 505, 679, and 999, representing HexNAc2+, Fuc1HexNAc2+, and NeuAc1Fuc1Hex1HexNAc+, respectively, were each detected in fewer than 600 spectra (supplemental Table S1.2), or less than 0.2% total after given a summed ion intensity weighting (supplemental Table S1.3). This MS2 spectral counting and/or ion intensity summation for the selected MS2 ions allows a quick assessment of the kind of terminal glycotopes or glycosylation features that characterize a glycome and their relative abundance, with good reproducibility demonstrated across the 10x concentration range analyzed (Fig 3B–3D, supplemental Fig. S5A). To further distinguish the isomeric fucosylated glycotopes identified by a common MS2 ion will require detecting their respective diagnostic MS3 ion in as many productive pd-MS3 afforded (supplemental Figs. S5B, S5C). A comparable linear response for their summed MS3 ion intensities over 10x concentration was similarly observed, allowing consistent estimation of their relative abundance (supplemental Table S1.4, supplemental Fig. S5D). Additional triplicate analyses on the AGS O- and N-glycans (supplemental Table S2) indicated a good reproducibility for the identified glycotopes and their relative abundance (Fig 3E). The N-glycans expressed relatively more of terminal HexNAc and less of sialyl LacNAc than the O-glycans. Both carried comparable amount of mono- and di-fucosylated glycotopes predominantly on type 2 chain, resulting in mostly LeX, H2, and LeY.

MS2 Data Mining for Sulfated Glycotopes by GlyPick

Applying the same concept described above for mining the data sets of nonsulfated glycans, GlyPick can similarly filter out true sulfated glycan MS2 spectra acquired in negative ion mode based on their containing at least one of the diagnostic MS2 ions for known sulfated glycotopes (9), and quantify their relative abundance by summed ion intensities. The MS2 data sets of 2 independently prepared AGS sulfated O-glycan samples acquired using 2 different nanoLC conditions on 2 different Orbitrap Fusion systems revealed a minimum amount of m/z 167 and 195 to account for terminal Gal-6-O-sulfate and internal GlcNAc-6-O-sulfate in both samples, the sulfated glycotopes of which was dominated instead by Gal-3-O-sulfate (Gal3S) defined by m/z 153 and 181 (Fig 4C). Interestingly, a slight increase in the relative abundance of Gal3S was detected in the more recently prepared sample analyzed on Orbitrap Fusion Lumos, accompanied by a more conspicuous increase in m/z 253 and 283 that defines a terminal sulfated Gal, concomitant with a decrease in m/z 371 and 528. This suggests that the Gal3S carried on a LacNAc was reduced relative to Gal3S on its own, which is in accord with the significant increase in the 2 peaks eluting at 39.68 (m/z 1199) and 39.82 (m/z 1373) min (supplemental Fig. S2 left panel, Fig 4A), identified as carrying a Gal3S on the 3-arm coupled with either a LeX or LeY on the 6-arm (supplemental Figs. S3, Fig. 4B).

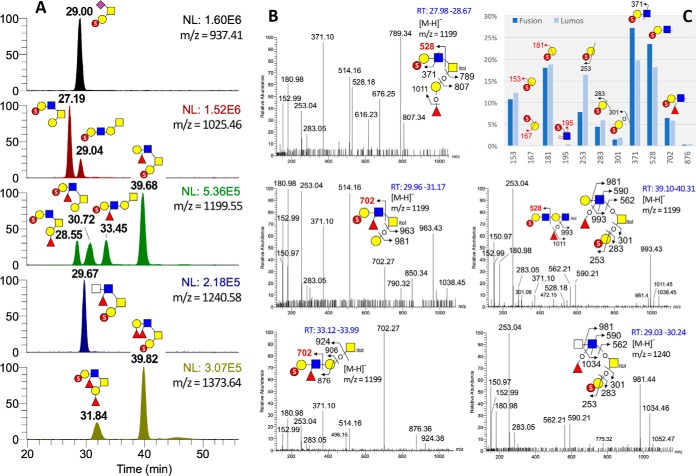

Fig. 4.

NanoLC-MS2-pd-MS3 analysis of permethylated sulfated AGS O-glycans. A, Extracted ion chromatograms for the major permethylated sulfated AGS O-glycans, with the deduced structure for each resolved peak annotated using the standard symbol nomenclature system (35). Compared with the data shown in supplemental Fig. S2, the elution patterns are fairly reproducible despite shifts in retention times because of using a different nanoLC conditions, and with MS2-pd-MS3 data acquired on Lumos instead of Orbitrap Fusion for an independently prepared batch of permethylated AGS O-glycan sample. Only the 4 HCD MS2 spectra for the 4 chromatographically resolved peaks of m/z 1199 and the one for m/z 1240 are shown here in (B). These are like the trap CID MS2 spectra acquired on Oribitrap Fusion shown in supplemental Fig. S3 except for the additional presence of the low mass diagnostic ions. The relative amount of the distinct sulfated glycotopes as represented by the summed intensity of respective diagnostic HCD MS2 ions is shown in (C) for the 2 different AGS O-glycan sample preparations and analyses. The GlyPick-processed MS2-pd-MS3 data set for the sample acquired on Lumos can be found in supplemental Table S3.

By fitting the inferred monoisotopic precursor mass of each MS2 scan to glycosyl composition within the user-defined constrains and output the resulting entries in csv format that can be further filtered, edited, color coded and sorted at will using the built-in Excel functions (see supplemental Table S3), GlyPick greatly facilitates manual verification of the nanoLC-MS2-pd-MS3 data set. It enables users to home in directly on relevant MS2 scans of the more abundant glycans, or those carrying the targeted glycotopes, for structural assignment. As shown here (Fig 4B) for the 4 isomeric peaks of m/z 1199 (Fuc1Hex2HexNAc2S), only the second and third isomers in elution order produced the diagnostic MS2 ion at m/z 702 for a sulfated fucosylated LacNAc carried on the 6-arm of a core 2 structure and 3-arm of an extended core 1 structure, respectively. Because the sulfate is determined to be on terminal Gal3S, and m/z 371 defined a type 2 chain, the sulfated fucosylated LacNAc can thus be assigned as sulfo LeX. The first and fourth isomers, on the other hand, carried a sulfo LacNAc instead as revealed by the presence of m/z 528. The 4th peak comprised 2 isomers, the major one being core 2 structure with a Gal3S on the 3-arm coupled with a LeX on the 6-arm, whereas the minor one appears to be a di-LacNAc fragment derived from larger glycans that was produced during sample preparation and carried a sulfo LacNAc at its nonreducing end. Going through the GlyPick-collated data set by MS1 peak intensity, the only unanticipated major component revealed is the one at m/z 1240, which could be manually assigned by referring to its MS2 scans as a core 2 structure carrying a rare fucosylated HexNAc2 glycotope on the 6-arm with a Gal3S on the 3-arm (Fig 4B). Notably, all O-glycans with a single Gal3S on the 3-arm were found to produce a diagnostic ion at m/z 150.97 that is more abundant than m/z 152.99.

Identifying Rare Disialylated LacNAc Glycotopes Facilitated by GlyPick

Although GlyPick allows postdata acquisition query of any glycotope or structural feature defined by a diagnostic MS2 ion retrospectively, it can also be used in a more forceful and targeted manner in conjunction with the MS2-pd-MS3 scan function. This is demonstrated from within an integrated glycomic workflow aiming at identifying the full ensemble of glycotopes carried on the N-glycans of mouse brain striatum, including the possible occurrence of a terminal disialyl capping unit implicated by striatal-enriched expression of the α2–8-sialyltransferase, ST8Sia3 (19–21). Our first step involved a rapid MALDI-MS screening of the permethylated N-glycans, which would inform the N-glycomic sample quality, quantity and complexity to guide subsequent nanoLC-MS/MS analysis. As expected, the brain N-glycans are dominated by complex type structures that can be tentatively assigned as bi- to tetra-antennary, core fucosylated, with nonextended GlcNAc, or fucosylated and/or sialylated LacNAc termini (Fig 5A). Although a few major peaks can be directly subjected to MALDI MS/MS to verify the structural assignment, it is not practically feasible to attempt a comprehensive MS2 analysis, particularly for the very low abundant peaks above m/z 4500 that are the most likely candidates carrying disialylated antenna. Instead, a single nanoLC-MS2-pd-MS3 run followed by data mining using GlyPick would more efficiently accomplish the glycotope mapping at much higher sensitivity. It revealed that the mouse brain striatum is mostly decorated with terminal GlcNAc, sialyl LacNAc and LeX (Fig 5B).

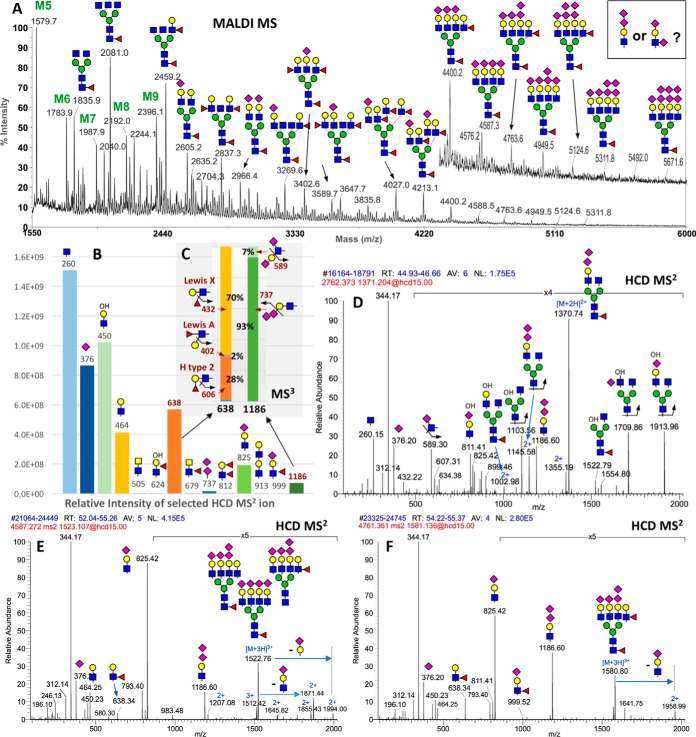

Fig. 5.

Glycotope-centric glycomic analysis of N-glycans from mouse brain striatum. A, MALDI-MS mapping of the permethylated N-glycans, with major peaks annotated using the standard symbol nomenclature system ((35) and (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310273/)), based primarily on glycosyl composition. Several isomeric permutations for the actual glycotopes carried on each structure are possible and indeed verified by subsequent LC-MS2/MS3 analyses. Data analysis by Glypick allows rapid identification and assessment of the relative abundance of expressed glycotopes at glycomic level based on the summed intensity of diagnostic MS2 ions (B), and MS3 ions in the case of isomeric fucosylated and disialylated Hex1HexNAc1 (C). N-glycans carrying the disialylated glycotopes can be inferred from the compiled data (supplemental Table S4) and verified by manual interpretation of their respective MS2 scans averaged over their elution time, exemplified here for a disialylated mono-antennary N-glycan (D), and 2 tetra-sialylated tatra-antennary N-glycans carrying either one (E) or two (F) fucoses. For the latter two, more than one isomeric structures are clearly present based on the complement of oxonium ions detected. The MS2 data will not inform which specific glycotopes are carried on which of the 4 antennae. All MS2 ions are singly charged except those annotated with 2+ or 3+.

More importantly, we could pick up low level of diagnostic ions for disialylated glycotope based on m/z 737 (NeuAc2+) and 1186 (NeuAc2-Hex1HexNAc+), the confident identification of which is secured via the programmed target pd-MS3 (Fig 5C). In the case of m/z 737, MS3 should produce a terminal NeuAc+ at m/z 376 to confirm that it is indeed a NeuAc-NeuAc unit. Because m/z 737 was selected in the first place at MS2 level by accurate mass, failure to yield productive MS3 does not necessarily discredit its identification but positive MS3 would additionally imply that it was of significant ion intensity. In the case of m/z 1186, we not only identified, for the first time by glycomic analysis, a NeuAc-NeuAc-capped LacNAc based on the MS3 ion at m/z 737, but also a small % of NeuAc-Hex-3(NeuAc)HexNAc disialylated glycotope based on m/z 589. This MS3 ion can only be derived from NeuAc-6HexNAc+ after elimination of the NeuAc-Hex unit attached to the C3 position of the HexNAc, consistent with a type 1 chain, Gal-3GlcNAc, sialylated at both terminal Gal and internal GlcNAc. The MS3 data also confirmed that in the case of fucosylated Hex-HexNAc, a majority was based on type 2 chain comprising both H2 and LeX, with only a very small % contributed by LeA. Other glycotopes defined by specific MS2 ions including lacdiNAc (HexNAc2, m/z 505), fucosylated lacdiNAc (m/z 679), LeY/B (difucosylated Hex1HexNAc1, m/z 812), and sialyl LeX (m/z 999) were deemed insignificantly expressed at the glycomic level.

From Glycotopes to Comprehensive Listing of Glycans with Supportive MS2/MS3

The next level of data analysis is to locate the identified glycotopes on specific N-glycan structures and, ideally, to provide supporting MS2 data for each of the major MS1 peaks detected by MALDI-MS and/or nanoLC-MS/MS. This would require tracking each of the filtered glycan MS2 scans back to its preceding MS1 scan, and to mass fit the inferred monoisotopic precursor to glycosyl composition. In the first iteration, only fully permethylated and protonated precursors were considered to restrict the mathematical permutations. In general, many other precursors carrying NH4+, Na+ and/or K+ were also detected at lower abundance and triggered for MS2, along with those carrying 1–2 degrees of under-methylation, and those corresponding to nonreduced fragments (derived from sample processing) or fragment ions (derived from in source fragmentation). Therefore, in addition to those MS2 scans that would fit exact glycosyl compositions within the applied constraints, there are many more that would not but still contain the targeted diagnostic ions. A significant proportion of these arise from mis-identified monoisotopic peak, which is a genuine problem intrinsic to analysis of this nature. As the N-glycan size increases, so are the possible permutations particularly for samples carrying multiple Fuc and NeuAc. We noted that the glycosyl composition Fuc2HexNAc3 differs from NeuAc3 by a mere 0.036 Da, NeuAc2Fuc1 differs from Hex2HexNAc2 by 2.016 Da, and Fuc3HexNAc1 differs from NeuAc1Hex2 by 1.979 Da. The 2 Da differences would complicate the process of picking the correct monoisotopic precursor from an overlapping isotopic cluster. This is exemplified by two overlapping triply charged (M+3H)3+ precursors with a theoretical monoisotopic mass at m/z 1763.217 versus 1763.889 (supplemental Fig. S6). Even with the excellent high resolution afforded by Orbitrap, the third and most abundant isotopic peak of the former at m/z 1763.886 could not be resolved from the monoisotopic peak of the latter. Further issues include low ion statistics for weak signals and the problem of including more than 1 precursors within the 2 Th isolation window to produce multiplexed MS2 spectra. None of these is easily solved problem given the extreme heterogeneity in coeluting isobaric and isomeric structures, which impart a high level of uncertainty and errors in retrofitting the actual precursors with correct glycosyl composition.

Despite the inherent shortcomings, GlyPick will provide the best fit (< 5 ppm) for inferred monoisotopic precursors, compute the theoretical m/z values for the singly charged (M+Na)+ equivalents for ease of referring back to MALDI-MS data, group all MS2/MS3 scans tracking back to the same precursors, sum the MS1 precursor and selected MS2 ion intensity for each unique glycan precursor thus identified and output this in Excel format (supplemental Table S4), which can be further edited and mined by users similar to that described above for the simpler case of mono-sulfated O-glycans. A final “A-list” of 454 grouped entries containing 3860 MS2 spectral counts was registered after further editing out those entries fitted to unreasonable glycosyl composition, usually the ones with the number of Hex more than HexNAc by ≥ 2 residues, or carrying excessive numbers of Fuc or Sia relative to Hex and HexNAc. All major MALDI-MS peaks annotated (Fig 5A) are contained within this list, which matched well the grouped entries with highest summed MS1 ion intensity. MS2 scans that led to productive MS3 and which matched to more abundant precursor intensities could then be manually examined to verify as many N-glycan structures carrying the target glycotope (see supplemental Table S5 and supplemental Fig. S7 for a filtered subset of MS2 scans containing the MS3-validated diagnostic MS2 ion at m/z 1186 for the disialyl LacNAc glycotope). For simplicity, a listing of only the more abundant grouped entries with summed MS1 and MS2 intensities could also be output to support the assignment of major peaks detected by MALDI-MS.

Of note, we showed that many N-glycans including the smallest one with only a single antenna (Fig 5D), as well as those larger tetra-sialylated tetra-antennary structures (Fig 5E, 5F) could carry a disialylated antennae but would not normally be annotated as such based on composition alone. The MS2 ion at m/z 1186 from each of these precursors were successfully auto-selected for pd-MS3 to yield the diagnostic NeuAc2+ ion at m/z 737 otherwise not obvious in their MS2 spectra. Interestingly, MS2 ion at m/z 999 indicative of sialyl LeX could be detected for the difucosylated structure, suggesting the presence of alternative isomeric structures. In fact, our comprehensive MS2/MS3 analyses revealed all possible permutations for the sialylation and fucosylation, as well as low level of type 1 chain-based glycotopes, which collectively contributed to the vast glycomic heterogeneity. However, it is also clear from this work which are the major glycotopes carried on the brain striatum N-glycans.

DISCUSSION

A glycotope-centric glycomic approach and its enabling computational tool aim not to identify as many glycans as confident as possible by matching the individual MS2 spectra to a spectral library or predicted MS2 ion sets derived from a predefined glycan database. The glyco-analysis community is still far from this goal of glycomics with many technical problems to overcome. In fact, it is valid to question the feasibility, cost-effectiveness and wisdom of such undertaking, given the vast isomeric and isobaric heterogeneity intrinsic to glycosylation. Particularly in cases of large, highly complex, multisialylated, multifucosylated N-glycans such as those of the brain N-glycome analyzed here, it is unlikely that any form of chromatography including the widely used poros graphitized carbon (PGC) nanoLC capable of resolving isomeric glycans in their native, reduced forms (22–24), will ever achieve a resolution at single glycan entity level. Data dependent MS2 acquisition invariably generates multiplexed spectra, even with the narrowest precursor isolation width. Assignment of positive spectrum match to a single dominant structure is delusive and only at the expenses of minor isomeric or isobaric constituents. Moreover, many isomeric glycan structures have almost identical MS2 spectra, whereby further stages of MSn analysis will at best qualitatively inform the presence of its individual constituents. All these must be considered in the context of achievable precision and sensitivity at reasonable throughput and accessibility to nonexperts.

We argue that a more productive approach that is also more biologically relevant is to first and foremost quantitatively map all the expressed glycotopes at the glycomic level. GlyPick enables the requisite automation and high throughput, making the proposed platform amenable to all and well suited for large scale comparative glycomic analysis of biological samples. As demonstrated in this work, the well-established elimination of substituents from the C3 position of an oxonium ion (14) is sufficient to allow unambiguous assignment of the isomeric constituents of a glycotope. On the plus side, any structural feature that can be defined by a unique MS2 ion and preferably also confirmed by an MS3 ion can be thus identified and relatively quantified. This includes the precise location of sulfate on terminal glycotopes, as determined in negative ion mode. It is also fully compatible with mining the LC-MS/MS data of native glycans such as those separated on a PGC column because GlyPick allows input of any user-specified MS2 ions. On the other hand, structural features that will not directly yield a diagnostic ion can potentially be defined by incorporating additional chemo-enzymatic manipulation steps. For example, recent work by Jiang et el demonstrated that α2–3 and 2–6-sialic acids can be differentially derivatized by dimethylamidation followed by permethylation (25), resulting in 13 mass units difference between a methyl esterified and dimethyamidated sialic acid depending on whether it is 2–3 or 2–6-linked to Gal, respectively. This allows production of distinctive NeuAc+ and NeuAc-containing oxonium ions for a variety of α2–3/2–6-linked sialylated glycotopes to be distinguished and relatively quantified using our workflow. The use of α2–3-specific sialidase and quantifying the reduced intensity of sialylated glycotopes relative to nontreated sample is another viable approach. Granted, not all features can thus be solved at present but neither can it by any other single method at sufficiently high sensitivity.

In contrast to the rather straightforward mapping of glycotopes based on summed intensity of MS2 ions, assigning the glycosyl compositions for each of the precursors that yield the respective diagnostic fragment ions is more problematic. Some of the technical challenges and pitfalls have been discussed when referring to the brain N-glycomic data set. It should be emphasized that GlyPick does not attempt to identify glycans and thus there is no associated probabilistic scoring or false discovery rate issue. The most common source of error is failure to infer correctly the monoisotopic precursors, resulting in a mass value that does not or incorrectly fit a permissible glycosyl composition. This is, however, less an issue for MS1 signals of higher intensity. As reflected from the grouping of all precursors with the same mass values and summing of their MS1 ion intensities (supplemental Table S4), the major components thus stand out from the list correlates well with the major assigned MALDI-MS peaks. GlyPick faithfully collates all MS2 and MS3 spectra acquired, summed their ion intensities, and computes the fitting glycosyl compositions for each of the precursors, without attempting to identify them by sophisticated search and scoring algorithm. It facilitates manual interpretation, especially in plowing through thousands of spectra, but does not substitute for the eventual structural assignment effort.

Much of what we now know of the brain N-glycome stems from early comprehensive studies in the 90s using large amount (∼200 g) of whole brains from adult rats as starting materials to isolate, fractionate, and characterize in detail the released N-glycans (26, 27). In addition to about 15% of high mannose type structures, it was shown that the neutral N-glycans were dominated by core fucosylated biantennary structures terminating with Galβ1–4GlcNAc (LacNAc), α3-fucosylated LacNAc (LeX), or nongalactosylated β-GlcNAc. A substantial portion of the nonfucosylated LacNAc in these and most of the larger tri- and tetra-antennary N- glycans were NeuAcα2–3-sialylated, along with a significant amount of disialylated antenna in the form of NeuAcα2–3Galβ1–3(NeuAcα2–6)GlcNAc, as well as nonsialylated type 1 chain Galβ1–3GlcNAc and a small amount of sialyl LeX. These “brain-type” N-glycosylation pattern and glycotopes identified are well-conserved between rat and mouse brains and reproducibly observed in all subsequent modern day MALDI-MS-based mapping of the brain N-glycome using much less materials and without the extensive prefractionation (28–30). However, conspicuously absent from these single dimensional MS profile was any evidence that would support the presence of disialylated LacNAc antennae beyond simple inference by molecular mass and hence overall assigned glycosyl compositions. More recently, a PGC LC-MS/MS-based mapping was applied to native mouse brain N-glycans (31) but structural details on terminal glycotopes were equally not pinned down because MS2 alone cannot distinguish the isomeric fucosylated or disialylated glycotopes. In contrast, we have been able to provide conclusive supporting evidence for all the major glycotopes in single nanoLC-MS2-pd-MS3 run, including resolving the 2 different disialylated termini and the LeX-dominant fucosylated glycotopes, using less than 5% of the permethylated N-glycans derived from the striatum of a single mouse brain. We were also able to map a full range of the sulfated glycotopes in a different fraction collected from the same sample after permethylation (unpublished data), an advantage not afforded by MS analysis of native glycans.

The current emphasis for a majority of mammalian glycomic analysis is high throughput and sensitivity, to reliably detect glycosylation changes or differences using less amount but larger number of biological samples (32–34). This is needed to satisfy the requisite statistical significance over high individual variations. Decades of more conventional complete structural analysis have laid a strong foundation for understanding the range of mammalian glycans that can be made by a restricted set of glyco-genes. Although the exact number of glycan entities may be large and indefinite because of unlimited permutation of branching and extension before terminal capping, the glycotopes and structural features that matter are not. In fact, a survey of current glycomic literature seldom hits on reports of novel glycotopes. This is likely because most efforts being undertaken are not conducive to delineate among the known isomeric glycotopes, let alone to discover new ones. Our workflow, in contrast, allows for comprehensive MS2/MS3 data acquisition and semi-quantitative analysis, homing in on distinguishing the relative amounts of isomeric glycotopes. It strikes the optimal balance among high throughput, sensitivity and precision. It similarly relies much on presumptive structural knowledge of the stereochemistry of Hex and HexNAc residues, but does validate the critical linkages that identify the glycotopes. It is particularly powerful for rapid survey, comparative or confirmatory, glycomic mapping and can be equally applied to any glycomic sample searching for known or novel glycotopes.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The MS raw data files for the permethylated AGS sulfated O-glycans and mouse brain striatal N-glycans can be accessed at MassIVE (ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000081184).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Academia Sinica Common Mass Spectrometry Facilities located at Institute of Biological Chemistry for all mass spectrometry data acquisition, and the technical assistance provided by its staff scientist and technicians.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: C.T.H. designed and carried out the LCMS/MS workflow, data analysis and software development; P.W.W. developed and wrote the software; H.C.C., Y.Y.C., and S.H.W. contributed to glycomic sample preparation and data analysis; Y.C. provided the brain glycomic samples and data interpretation; K.H.K. conceived the experimental workflow, performed data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

* This work was supported by Academia Sinica and Taiwan Ministry of Science (MoST 102-2311-B-001-026-MY3 to KKH and MoST 103-2321-B-001-068 to YC.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- CID

- collision-induced dissociation

- AGC

- automatic gain control

- DDA

- data dependent acquisition

- FA

- formic acid

- GUI

- graphic user interface

- HCD

- higher energy collision dissociation

- LacNAc

- N-acetyllactosamine

- lacdiNAc

- N,N′-diacetyllactosamine

- LeA/X

- Lewis A or X

- LeY/B

- Lewis Y or B

- NCE

- normalized collision energy

- pd-MS3

- product dependent MS3

- PGC

- poros graphitized carbon

- XIC

- extracted ion chromatogram.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moremen K. W., Tiemeyer M., and Nairn A. V. (2012) Vertebrate protein glycosylation: diversity, synthesis and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 448–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zaia J. (2010) Mass spectrometry and glycomics. OMICS 14, 401–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wuhrer M. (2013) Glycomics using mass spectrometry. Glycoconj. J. 30, 11–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ashline D. J., Lapadula A. J., Liu Y. H., Lin M., Grace M., Pramanik B., and Reinhold V. N. (2007) Carbohydrate structural isomers analyzed by sequential mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 79, 3830–3842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reinhold V., Zhang H., Hanneman A., and Ashline D. (2013) Toward a platform for comprehensive glycan sequencing. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 866–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jang-Lee J., North S. J., Sutton-Smith M., Goldberg D., Panico M., Morris H., Haslam S., and Dell A. (2006) Glycomic profiling of cells and tissues by mass spectrometry: fingerprinting and sequencing methodologies. Methods Enzymol. 415, 59–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu S. Y., Wu S. W., Hsiao H. H., and Khoo K. H. (2009) Enabling techniques and strategic workflow for sulfoglycomics based on mass spectrometry mapping and sequencing of permethylated sulfated glycans. Glycobiology 19, 1136–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khoo K. H., and Yu S. Y. (2010) Mass spectrometric analysis of sulfated N- and O-glycans. Methods Enzymol. 478, 3–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng C. W., Chou C. C., Hsieh H. W., Tu Z., Lin C. H., Nycholat C., Fukuda M., and Khoo K. H. (2015) Efficient mapping of sulfated glycotopes by negative ion mode nanoLC-MS/MS-based sulfoglycomic analysis of permethylated glycans. Anal. Chem. 87, 6380–6388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng P. F., Snovida S., Ho M. Y., Cheng C. W., Wu A. M., and Khoo K. H. (2013) Increasing the depth of mass spectrometry-based glycomic coverage by additional dimensions of sulfoglycomics and target analysis of permethylated glycans. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 6683–6695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ashline D., Singh S., Hanneman A., and Reinhold V. (2005) Congruent strategies for carbohydrate sequencing. 1. Mining structural details by MSn. Anal. Chem. 77, 6250–6262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nairn A. V., Aoki K., dela Rosa M., Porterfield M., Lim J. M., Kulik M., Pierce J. M., Wells L., Dalton S., Tiemeyer M., and Moremen K. W. (2012) Regulation of glycan structures in murine embryonic stem cells: combined transcript profiling of glycan-related genes and glycan structural analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37835–37856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ritamo I., Rabina J., Natunen S., and Valmu L. (2013) Nanoscale reversed-phase liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry of permethylated N-glycans. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 2469–2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dell A. (1987) F.A.B.-mass spectrometry of carbohydrates. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 45, 19–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Egge H., and Peter-Katalinic J. (1987) Fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry for structural elucidation of glycoconjugates. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 6, 331–393 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou S., Hu Y., and Mechref Y. (2016) High-temperature LC-MS/MS of permethylated glycans derived from glycoproteins. Electrophoresis 37, 1506–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu H., Sadygov R. G., and Yates J. R. 3rd. (2004) A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal. Chem. 76, 4193–4201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffin N. M., Yu J., Long F., Oh P., Shore S., Li Y., Koziol J. A., and Schnitzer J. E. (2010) Label-free, normalized quantification of complex mass spectrometry data for proteomic analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 83–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoshida Y., Kurosawa N., Kanematsu T., Taguchi A., Arita M., Kojima N., and Tsuji S. (1996) Unique genomic structure and expression of the mouse alpha 2,8-sialyltransferase (ST8Sia III) gene. Glycobiology 6, 573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mazarei G., Neal S. J., Becanovic K., Luthi-Carter R., Simpson E. M., and Leavitt B. R. (2010) Expression analysis of novel striatal-enriched genes in Huntington disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 609–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rinflerch A. R., Burgos V. L., Hidalgo A. M., Loresi M., and Argibay P. F. (2012) Differential expression of disialic acids in the cerebellum of senile mice. Glycobiology 22, 411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruhaak L. R., Deelder A. M., and Wuhrer M. (2009) Oligosaccharide analysis by graphitized carbon liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394, 163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hua S., An H. J., Ozcan S., Ro G. S., Soares S., DeVere-White R., and Lebrilla C. B. (2011) Comprehensive native glycan profiling with isomer separation and quantitation for the discovery of cancer biomarkers. Analyst 136, 3663–3671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jensen P. H., Karlsson N. G., Kolarich D., and Packer N. H. (2012) Structural analysis of N- and O-glycans released from glycoproteins. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1299–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiang K., Zhu H., Li L., Guo Y., Gashash E., Ma C., Sun X., Li J., Zhang L., and Wang P. G. (2017) Sialic acid linkage-specific permethylation for improved profiling of protein glycosylation by MALDI-TOF MS. Anal Chim Acta 981, 53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Y. J., Wing D. R., Guile G. R., Dwek R. A., Harvey D. J., and Zamze S. (1998) Neutral N-glycans in adult rat brain tissue–complete characterisation reveals fucosylated hybrid and complex structures. Eur. J. Biochem. 251, 691–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zamze S., Harvey D. J., Chen Y. J., Guile G. R., Dwek R. A., and Wing D. R. (1998) Sialylated N-glycans in adult rat brain tissue–a widespread distribution of disialylated antennae in complex and hybrid structures. Eur. J. Biochem. 258, 243–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. North S. J., Chalabi S., Sutton-Smith M., Dell A., and Haslam S. M. (2010) Mouse and Human Glycomes. In: Cummings R. D., and Pierce J. M., eds. Handbook of Glycomics, pp. 263–327, Academic Press/Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gizaw S. T., Koda T., Amano M., Kamimura K., Ohashi T., Hinou H., and Nishimura S. (2015) A comprehensive glycome profiling of Huntington's disease transgenic mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1850, 1704–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gizaw S. T., Ohashi T., Tanaka M., Hinou H., and Nishimura S. I. (2016) Glycoblotting method allows for rapid and efficient glycome profiling of human Alzheimer's disease brain, serum and cerebrospinal fluid towards potential biomarker discovery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 1716–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ji I. J., Hua S., Shin D. H., Seo N., Hwang J. Y., Jang I. S., Kang M. G., Choi J. S., and An H. J. (2015) Spatially-resolved exploration of the mouse brain glycome by tissue glyco-capture (TGC) and nano-LC/MS. Anal. Chem. 87, 2869–2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zoldos V., Horvat T., and Lauc G. (2013) Glycomics meets genomics, epigenomics and other high throughput omics for system biology studies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cummings R. D., and Pierce J. M. (2014) The challenge and promise of glycomics. Chem. Biol. 21, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shubhakar A., Reiding K. R., Gardner R. A., Spencer D. I., Fernandes D. L., and Wuhrer M. (2015) High-Throughput Analysis and Automation for Glycomics Studies. Chromatographia 78, 321–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Varki A., Cummings R. D., Aebi M., Packer N. H., Seeberger P. H., Esko J. D., Stanley P., Hart G., Darvill A., Kinoshita T., Prestegard J. J., Schnaar R. L., Freeze H. H., Marth J. D., Bertozzi C. R., Etzler M. E., Frank M., Vliegenthart J. F., Lutteke T., Perez S., Bolton E., Rudd P., Paulson J., Kanehisa M., Toukach P., Aoki-Kinoshita K. F., Dell A., Narimatsu H., York W., Taniguchi N., and Kornfeld S. (2015) Symbol Nomenclature for Graphical Representations of Glycans. Glycobiology 25, 1323–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MS raw data files for the permethylated AGS sulfated O-glycans and mouse brain striatal N-glycans can be accessed at MassIVE (ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000081184).