Abstract

Introduction

Chinese medicine is commonly used to combine with pharmacotherapy for the treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Six Chinese herb formulas involving Weijing decoction, Maxingshigan decoction, Yuebijiabanxia decoction, Qingqihuatan decoction, Dingchuan decoction and Sangbaipi decoction are recommended in Chinese medicine clinical guideline or textbook, to relieve patients with phlegm-heat according to Chinese syndrome differentiation. However, the comparative effectiveness among these six formulas has not been investigated in published randomised controlled trials. We plan to summarise the direct and indirect evidence for these six formulas combined with pharmacotherapy to determine the relative merits options for the management of AECOPD.

Methods and analysis

We will perform the comprehensive search for the randomised controlled trials to evaluate the effectiveness of six Chinese herb formulas recommended in Chinese medicine clinical guideline or textbook. The combination of pharmacotherapy includes bronchodilators, antibiotics and corticosteroids that are routinely prescribed for AECOPD. The primary outcome will be lung function, arterial blood gases and length of hospital stay. The data screening and extraction will be conducted by two different reviewers. The quality of RCT will be assessed according to the Cochrane handbook risk of bias tool. The Bayes of network meta-analysis (NMA) will be conducted with WinBUGS to compare the effectiveness of six formulas. We will also use the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) to obtain the comprehensive rank for these treatments.

Ethics and dissemination

This review does not require ethics approval and the results of NMA will be submitted to a peer-review journal.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO (CRD42016052699).

Keywords: Chinese Herb Formula, Acute Exacerbation Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (aecopd), Systematic Review, Network Meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first meta-analysis to compare the Chinese herb formula combined with pharmacotherapy for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD).

The results of this study will provide the additional evidence for the clinical guideline and help the clinical practitioners to make decision for the treatment of AECOPD.

Although the comprehensive search will be performed in our study, potential unpublished trials are inevitable. This will introduce some bias.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common respiratory disease characterised by persistent airflow limitation and abnormal inflammatory response in airways.1 A recent survey reported that the estimated COPD prevalence was 6.2% in nine Asia-Pacific territories.2 This condition has resulted in an economic and social burden with the substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide.3 4 A survey estimates that COPD will become the third leading cause of death worldwide in 2030.5 Acute exacerbation of COPD is defined as the sustain worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variations.1 It has a considerable impact on the patients’ health status, lung function and even increases the risk of death.6–8 The clinical guideline recommended pharmacological therapies for the management of acute exacerbation including bronchodilators, antibiotics, corticosteroids and some other respiratory support. Despite the effectiveness of these therapies, acute exacerbation still occurs frequently and is significantly associated with morbidity and mortality.9 Moreover, these therapies have been associated with some side effects such as tremour, hyperglycaemia, candidiasis and antibiotic resistance.9 Clinicians should balance the effectiveness and safety of these pharmaceutical interventions for patients.

Chinese herb medicine is widely prescribed as an adjunct to western medicine to manage acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) in clinical guideline. Although CHM is not the mainstream for treating COPD, it has become increasingly accepted as a form of complementary or complementary medicine in western countries.10 Chinese herb formulas combined with routine pharmacotherapy have showed the promising benefits on lung function, arterial blood gases, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) scoring and 6 min walk test (6MWT) when compared with routine pharmacotherapy alone.11 12 Six Chinese herb formulas: Weijing decoction, Maxingshigan decoction, Yuebijiabanxia decoction, Qingqihuatan decoction, Dingchuan decoction and Sangbaipi decoction are representative recipes to treat patients with AECOPD of phlegm-heat syndromes in Chinese medicine theory.13–15 Despite the difference of herb ingredients, all these formulas can be prescribed to clear phlegm-heat symptoms for the patients. They also will be modified mildly according to additional clinical symptoms. These formulas or active compounds of herb ingredients also show the effects on anti-inflammation, antioxidative stress and improve immune function which may shorten recovery time and reduce recurrence of AECOPD.16–21 Several systematic reviews synthesised the effectiveness of single formula.12 22 However, the paucity of evidence from direct comparison between these six formulas posed a challenge for clinicians to find the more effective therapeutic option.

Network meta-analyses (NMAs), a newer statistical technique, compared with the traditional pairwise meta-analysis, can evaluate the relative efficacy of multiple treatment comparisons including both direct and indirect comparisons.23–26 The combination of direct and indirect evidence may improve the precision for the estimated effect size.23 27–29 The major value of NMAs is that it can provide the ranking of treatment options according to their effectiveness, which is important for clinicians to make the best treatment choice.

Therefore, we plan to conduct this systematic review and NMAs to compare these six Chinese herb formulas combined with pharmacotherapy to determine their relative effectiveness and safety in the treatment of AECOPD.

Methods and analysis

Registration

The study protocol has been registered on international prospective register of systematic review (PROSPERO). The procedure of this protocol will be conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidance.30

Eligibility criteria

Type of study

We will include all the randomised controlled trials that investigated the effectiveness of six Chinese herb formulas combined with pharmacotherapy for the treatment of AECOPD.

Participants

COPD should be confirmed according to the standard diagnostic criteria including the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD);1 the British Thoracic Society, the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society or Chinese COPD guideline.31

Patients must be aged at least 18 years old and diagnosed as AECOPD with one or more following symptoms: increased cough frequency, increased sputum volume, increased dyspnoea.1 We will exclude studies of participants with other respiratory disease like asthma, bronchiectasia, pulmonary tuberculosis and so on.

Interventions and comparators

Interventions involving the combination of Chinese herb formulas with conventional pharmacotherapy are eligible. The interested Chinese medicine therapies include the following six formulas: Weijing decoction, Maxingshigan decoction, Yuebijiabanxia decoction, Qingqihuatan decoction, Dingchuan decoction and Sangbaipi decoction. The same conventional pharmacotherapy must be used in the comparator arm.

Outcome

The primary outcomes include: (1) lung function—forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), (2) arterial blood gases—PaO2 of oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2), (3) length of hospital stay.

The secondary outcomes include: (1) dyspnoea, (2) health-related quality of life, (3) hospital readmission for acute exacerbation, (4) effective rate32 and (5) adverse events.

Search strategy

We will perform the comprehensive search in both English and Chinese database involving PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, AMED, Chinese Biomedical Database (CBM), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chongqing VIP information (CQVIP) and Wanfang database, from their inceptions to December 2016. The following sources will also be searched to identify clinical trials which are in progress or completed: ClinicalTrials.gov and WHO clinical trials registry. The additional relevant studies will also be retrieved from the reference lists of systematic reviews and included studies. We will map search terms to controlled vocabulary if possible. In addition, the search strategy for selecting the fields of title, abstract or keyword will be different referring to the characteristics of databases. Search terms are grouped into three blocks (see table 1).

Table 1.

Search terms

| Search block | Search terms |

| Participants | Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive OR Bronchitis, Chronic OR Pulmonary Emphysema OR Emphysema OR COPD OR Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary OR COAD OR Chronic Obstructive Airway OR Chronic Obstructive Lung OR Chronic obstructive bronchopulmonary OR Chronic obstructive respiratory OR Chronic Airflow Obstruction OR Chronic Airflow Obstructive OR Chronic bronchitis OR Pulmonary emphysema OR Lung emphysema OR Chronic Airflow limitation. |

| Intervention | wejing decoction OR wejing tang OR sangbaipi decoction OR sangbaipi tang OR maxingshigan decoction OR maxingshigan tang OR yuebijiabanxia decoction OR yuebijiabanxia tang OR dingchuan decoction OR dingchuan tang OR qingqihuatan decoction OR qingqihuatan tang OR qingqihuatan pill |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR randomized OR placebo OR drug therapy OR randomly OR trial OR groups |

Study selection and data extraction

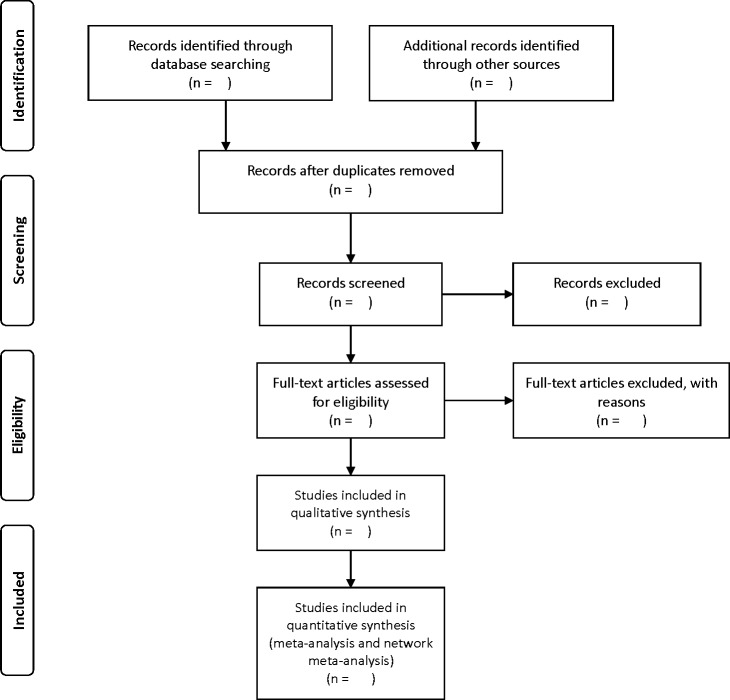

Literature retrieved citations will be managed by EndNote X6 software. Two independent reviewers (JL and JZ) will assess the title and abstract of the literature after removing duplications. The further screening will be performed to select eligible articles by reviewing the full-text. Any disagreement between the reviewers will be resolved by discussion with a third person (JC). The selection process will be provided in a PRISMA flow chart (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of searching and screening studies.

We will design the standardised database sheet for data extraction. Epidata software 3.1 (The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark, 2003–2008) will be used to extract data and check the consistency of information. The data extraction items include: first author, publication year, diagnose information, disease duration, stage, sample size, age, details of intervention, control and outcomes, treatment duration and follow-up period and adverse events.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the eligible studies will be evaluated according to the Cochrane collaboration’s risk of bias tool.33 The assessment details include: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias. Each domain will be assessed as ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’ according to the description details of eligible studies. Any discrepancies will be further discussed with a third reviewer (YH).

Statistical analysis

Pairwise meta-analysis

The conventional pairwise meta-analysis will be performed using random-effects model by Revman 5.3 software. Dichotomous data are presented as relative risk (RR) with 95% CI and continuous data are reported as mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. The χ2 test and I2 test will be conducted to convey the potential heterogeneity.

Network meta-analysis

The NMA will be conducted in a Bayesian hierarchical framework using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm by WinBUGS 1.4.3 software.34 The statistical heterogeneity of entire NMAs will be investigated by the magnitude of heterogeneity variance (τ2) estimated from the NMAs model.35 If the direct evidence is available, the combined estimation will be provided for NMAs. There are several methods to evaluate the potential difference in treatment effect estimated by direct and indirect comparisons.36–39 We will apply node splitting method to explore the inconsistency of the model.36 40 The deviance information criterion (DIC) will be used to assess the model fitness by comparing the fixed and random effects model and the lower DIC is preferred.41 To rank the probabilities of the best intervention for various treatments, we will use surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) and the mean ranks.42 SUCRA will be described with percentages, and larger values indicate the better ranks for the treatment. The generation of NMAs graphs and result figures will be performed by Stata software (Stata V.12). If the data are not available for quantitative analysis, we will describe and summarise the evidence.

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

The strategies employed to address the heterogeneity of pairwise meta-analysis also can be used in network analysis to tackle inconsistency.23 If the heterogeneity or inconsistency among the studies was detected, subgroup analysis will be conducted according to the effect modifiers, including sample size, severity of COPD, treatment duration. Also, the network meta-regression will be performed to explore the possible sources of inconsistency.43 We will perform the sensitivity analysis to explore the robust conclusions of primary outcomes if feasible. Different levels of the methodological quality of studies will influence the overall effects. Sensitivity analysis will be conducted by removing trails that report the non-random sequence generation.

Publication bias

Egger’s regression test will be performed to assess the publication bias of the included studies. If feasible, we will also convey whether the small study effects exist in a network of interventions by the statistical model.44

Quality of evidence

We will also assess the quality of evidence for the main outcomes with the GRADE (the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach.45 The five items will be investigated, including limitations in study design, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias.

Discussion

Chinese medicine has been used more than thousands of years for the treatment of respiratory condition. Nowadays, Chinese herb formula is commonly used as adjuvant therapy for the management of AECOPD in China. Multiple Chinese herb formulas are recommended in clinical guideline or textbook, while different formulas for each Chinese syndrome. Although few studies have reviewed the effective of the individual formula, the relative therapeutic effect differences among these formulas are still uncertain. Therefore, we plan to conduct NMA to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different Chinese herb formulas. This will be the first review to compare the effectiveness of six most commonly used Chinese herb formulas for the treatment of AECOPD. We hope that the results of our study will provide the clinical recommendation for patients with AECOPD in Chinese medicine clinical practice, and promote evidence-based for clinical Chinese medicine.

Ethics and dissemination

This review does not require the ethical approval since the study bases on the published evidence. The results of NMA will be reported according to the PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating NMA and submitted to a peer-review journal.46

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SL, XG and LW conceived and designed this study. SL and JC drafted the protocol. JL and JZ will conduct the search, data screening and extraction. SL, JC, YH, LW, LY and XG have critically reviewed the manuscript and approved it for publication.

Funding: This study is supported by Guangdong Provincial Department of Science and Technology, Guangdong, China (the project grant no 2014A020221020) and Clinical Research Special Project of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine (grant no YN2014LN10).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is a study protocol of network meta-analysis. No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: GOLD, 2016. http://www.goldcopd.org [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim S, Lam DC, Muttalif AR, et al. . Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: the EPIC Asia population-based survey. Asia Pac Fam Med 2015;14:4 10.1186/s12930-015-0020-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. . Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J 2006;27:397–412. 10.1183/09031936.06.00025805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Chronic respiratory diseases, burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en

- 6. Spencer S, Jones PW. Time course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Thorax 2003;58:589–93. 10.1136/thorax.58.7.589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, Ernst P. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax 2012;67:957–63. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, et al. . Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:332–8. 10.1164/rccm.200712-1869OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, et al. . Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology 2016;21:1152–65. 10.1111/resp.12780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu J, Zhang J, Zhao W, et al. . Cochrane systematic reviews of Chinese herbal medicines: an overview. PLoS One 2011;6:e28696 10.1371/journal.pone.0028696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chung VC, Wu X, Ma PH, et al. . Chinese herbal medicine and salmeterol and fluticasone propionate for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2016;95:e3702 10.1097/MD.0000000000003702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu S, Shergis J, Chen X, et al. . Chinese herbal medicine (weijing decoction) combined with pharmacotherapy for the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014;2014:1–12. 10.1155/2014/257012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences. Evidence-Based guidelines of clinical practice in chinese medicine. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences Publishing House, 2011. People’s Republic of China.. [Google Scholar]

- 14. China Association of Chinese Medicine. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of common internal disease in Chinese medicine: symptoms in Chinese medicine. People’s Republic of China: Chinese Academy of Chinese, Medical Sciences Publishing House, Beijing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15. China Association of Chinese Medicine. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of common internal disease in chinese medicine: diseases of modern medicine. Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2008. People’s Republic of China.. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jf L, Ds L. Experimental study on anti-inflammation and expelling phlegm effect of Dingchuan decoction. Chinese Journal of Experimental Traditional Medical Formulae 2002;8:40–1. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sq L. Effect of IL-8 in peripheral blood of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with Weijing decoction combined with western medicine. Medical information 2009;22:2728–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu L, Zhang HY. The pharmacological effect of Maxingshigan decoction. Drug research 2015:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Duval C, Augé N, Frisach MF, et al. . Mitochondrial oxidative stress is modulated by oleic acid via an epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent activation of glutathione peroxidase. Biochem J 2002;367:889–94. 10.1042/bj20020625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuk JE, Woo JS, Yun CY, et al. . Effects of lactose-beta-sitosterol and beta-sitosterol on ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation in actively sensitized mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2007;7:1517–27. 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perera WR, Hurst JR, Wilkinson TM, et al. . Inflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbation. Eur Respir J 2007;29:527–34. 10.1183/09031936.00092506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang XY, Yang ZL, Huang FH, et al. . Therapeutic effect and symptom changes of phlegm-clearing decoction combined with western medicine for COPD with acute exacerbation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chinese Archives of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2016;34:860–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, et al. . Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:130–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jansen JP, Crawford B, Bergman G, et al. . Bayesian meta-analysis of multiple treatment comparisons: an introduction to mixed treatment comparisons. Value Health 2008;11:956–64. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE, et al. . Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2008;17:279–301. 10.1177/0962280207080643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med 2004;23:3105–24. 10.1002/sim.1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. . The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hasselblad V. Meta-analysis of multitreatment studies. Med Decis Making 1998;18:37–43. 10.1177/0272989X9801800110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897–900. 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Group of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Branch of Respiratory Diseases, and Chinese Medical Association,. Guidance of diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (reversed edition in 2007),”. Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis 2007;30::8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zheng XY. Guidance for clinical research on New Drugs of TCM: China Medical Science Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version5.1.0, 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org

- 34. Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, et al. . WinBUGS - A bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput 2000;10:325–37. 10.1023/A:1008929526011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jackson D, Barrett JK, Rice S, et al. . A design-by-treatment interaction model for network meta-analysis with random inconsistency effects. Stat Med 2014;33:3639–54. 10.1002/sim.6188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, et al. . Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932–44. 10.1002/sim.3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu G, Welton NJ, Higgins JP, et al. . Linear inference for mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis: a two-stage approach. Res Synth Methods 2011;2:43–60. 10.1002/jrsm.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Song F, Altman DG, Glenny AM, et al. . Validity of indirect comparison for estimating efficacy of competing interventions: empirical evidence from published meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;326:472 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krahn U, Binder H, König J. A graphical tool for locating inconsistency in network meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:35 10.1186/1471-2288-13-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu G, Ades AE. Assessing evidence inconsistency in Mixed Treatment Comparisons. J Am Stat Assoc 2006;101:447–59. 10.1198/016214505000001302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, et al. . Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J R Stat Soc Ser B 2002;64:583–639. 10.1111/1467-9868.00353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salanti G, Marinho V, Higgins JP. A case study of multiple-treatments meta-analysis demonstrates that covariates should be considered. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:857–64. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chaimani A, Salanti G. Using network meta-analysis to evaluate the existence of small-study effects in a network of interventions. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:161–76. 10.1002/jrsm.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, et al. . Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e99682 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.