Abstract

Background

The integration of digital technology into everyday lives of young people has become widespread. It is not known whether and how technology influences barriers and facilitators to healthcare, and whether and how young people navigate between face-to-face and virtual healthcare. To provide new knowledge essential to policy and practice, we designed a study that would explore health system access and navigation in the digital age. The study objectives are to: (1) describe experiences of young people accessing and navigating the health system in New South Wales (NSW), Australia; (2) identify barriers and facilitators to healthcare for young people and how these vary between groups; (3) describe health system inefficiencies, particularly for young people who are marginalised; (4) provide policy-relevant knowledge translation of the research data.

Methods and analysis

This mixed methods study has four parts, including: (1) a cross-sectional survey of young people (12–24 years) residing in NSW, Australia; (2) a longitudinal, qualitative study of a subsample of marginalised young people (defined as young people who: identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; are experiencing homelessness; identify as sexuality and/or gender diverse; are of refugee or vulnerable migrant background; and/or live in rural or remote NSW); (3) interviews with professionals; (4) a knowledge translation forum.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approvals were sought and granted. Data collection commenced in March 2016 and will continue until June 2017. This study will gather practice and policy-relevant intelligence about contemporary experiences of young people and health services, with a unique focus on five different groups of marginalised young people, documenting their experiences over time. Access 3 will explore navigation around all levels of the health system, determine whether digital technology is integrated into this, and if so how, and will translate findings into policy-relevant recommendations.

Keywords: Adolescents, youth, health services accessibility, knowledge translation, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Design allows for breadth and depth of enquiry about barriers, facilitators and health system navigation.

Stakeholder engagement assists with recruitment and interpretation of findings and policy relevance.

Policy translation as part of study design optimises incorporation into new youth health policy.

Potential for recruitment bias due to sampling strategies.

Inclusion criteria for marginalised groups study will not capture the full range of young people who are potentially marginalised.

Background

The health and well-being of young people (12–24 years) are shaped by unique developmental factors as well as a range of social, cultural and environmental determinants. In high-income countries including Australia, mental health problems and chronic physical illness are the major health conditions experienced by young people.1 2 Timely access to appropriate healthcare is an important determinant of young people’s health. In primary care, identification of health risk behaviours and early intervention can mitigate some negative health trajectories.3 For young people with chronic health conditions, health risk behaviours occur at similar or higher rates compared with well peers,4 thus transition policies and programmes to prevent disengagement from healthcare have been established in many countries.5 Hospitalised young people have needs that require specific service delivery and policy responses, since developmental factors, legal minor status and professional discomfort can contribute to adverse events for adolescents in hospital.6 Despite evidence-based guidelines for ‘youth friendly’ health services,7 young people continue to have suboptimal experiences. A study across 11 developed countries found that young adults (18–25 years) had worse satisfaction with health services and significantly higher cost barriers compared with older adults.8

In Australia, access to and models of healthcare were described in the 1990s to early 2000s9–11 and have informed youth health policy.12 13 Despite these initiatives, healthcare has become more fragmented14 15 and presentations to emergency departments are increasing among young people, possibly due to general practitioner unavailability and cost.16 In the hospital sector, there is also major scope to improve ‘adolescent-friendliness.’17 Most importantly, since almost 100% of Australian young people have access to the internet18 and most have smartphones,19 evidence is now needed to understand how digital technology influences access to healthcare. A recent systematic review suggested that online mental health services may play a small role in facilitating access.20 Online interventions may also help facilitate some access to sexually transmitted infections (STI) testing.21

This study will update knowledge about access in the digital age, explore healthcare navigation and will embed a knowledge translation process to address the evidence of failure for research to be translated into policy and practice.22 There will be a focus on marginalised young people whose experiences have been less comprehensively studied. For example, a recent systematic review of homeless youth and healthcare access identified only 13 studies.23 Recent Australian studies exploring access among Indigenous young people24 and young people of refugee background25 have been small cross-sectional studies focusing on mental healthcare. Earlier research among young people living in rural and remote areas before the rise of digital technology identified that cost, confidentiality and provider availability were more prominent barriers compared with urban counterparts.26 A recent cross-sectional study of sexuality and gender diverse young people found that fear of discrimination hindered optimal healthcare.27 This study will target these groups of young people and explore barriers, navigation over time and the role of technology in access to healthcare.

This protocol describes a multifaceted, mixed methods study known as Access 3. It takes its name from the previous studies called Access Phase 128 and Access Phase 229 and was funded by the state health department of New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Access 3 aims to explore ways in which young people in NSW access, navigate and experience all levels of the health system, how digital technology is integrated into these processes, and to translate findings into practice and policy-relevant recommendations.

Methods and analysis

The Access 3 study objectives are to:

identify barriers and facilitators to accessing healthcare for young people in NSW and how these vary between groups;

describe experiences of young people accessing and navigating the health system in NSW;

describe health system inefficiencies for young people who are marginalised;

provide practice and policy-relevant knowledge translation of the research data.

Marginalised young people will be defined as meeting at least one of the following criteria:

living in rural/remote NSW;

being homeless or at risk of homelessness (using the cultural definition)30;

being of refugee background or a recently arrived migrant from a non-English speaking background;

being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander;

being same sex attracted or identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex or asexual.

These five groups have been selected to provide a purposive and varied sample, and our inclusion criteria are not intended to represent an exhaustive classification of all marginalised young people. However, by exploring the needs of young people belonging to one or more of these groups, we may also gain insight into the experiences of marginalised young people more broadly.

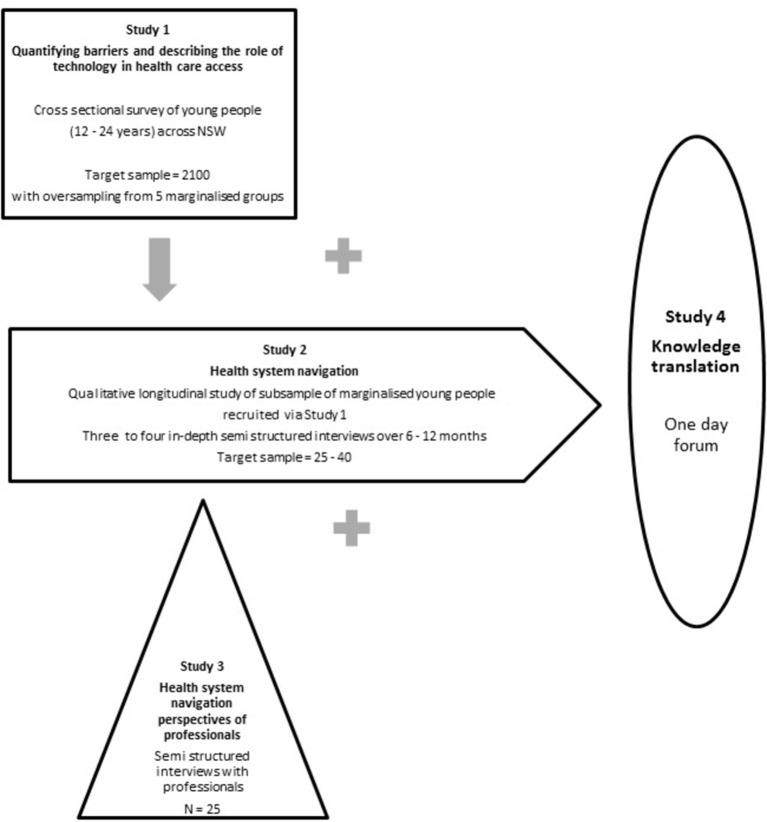

Access 3 comprises four separate but interconnected studies, illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Access 3 design. NSW, New South Wales.

Study 1

Aim

To describe and quantify barriers, facilitators, and how technology is used, to access healthcare, and how these vary by age, gender and marginalisation.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Participants

Non-probability sample of young people aged 12–24 years residing in NSW with oversampling of marginalised young people.

Recruitment

Online and offline. Online recruitment has included targeted emails to youth-relevant networks, social media (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram) and opportunistic online promotion of the survey. Offline recruitment has occurred face-to-face in education-linked settings, youth accommodation services and forums where groups of young people meet (eg, advocacy groups). To purposively sample marginalised young people, we have worked with networks and advocates from a range of organisations in rural areas, supported accommodation services, community organisations and services who work with or for homeless young people, sexuality diverse and gender diverse young people, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander young people, young people living in rural areas and young people of refugee or refugee-like background. We have also relied on convenience and snowball sampling methods to achieve our sample size.

Data collection

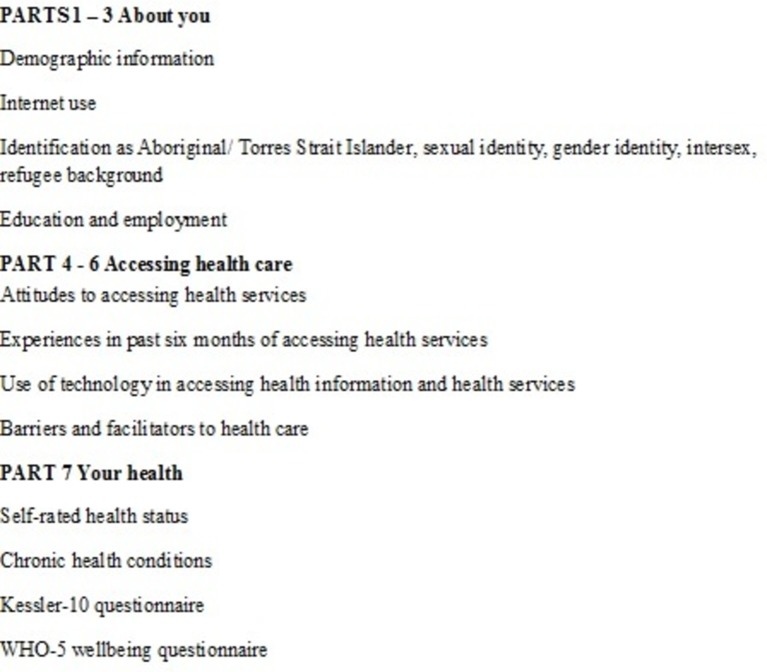

Anonymous questionnaire administered via an online survey platform or by hard copy. Data collection commenced in February 2016. The online survey was closed in February 2017, and hard copy data collection is about to close as of March 2017. The questionnaire was guided by published evidence28 29 31 about known barriers to access and ‘youth-friendliness’ indicators applicable to primary and community-based health services and hospitals. Questions about the impact of digital technology on whether, when and how to access healthcare were included. Demographic data were collected, as well as the presence of chronic health conditions and/or disability, and young people’s knowledge and attitudes to health services and accessing care. The questionnaire was developed in consultation with and piloted among a Youth Consultant group who also assisted with promotion of the survey. The questionnaire topic headings are listed in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Questionnaire topic headings for Study 1.

Analysis

Quantitative analysis, using the statistical software program version 23 SPSS,32 of the barriers and facilitators and use of digital technology, encountered by age, gender, rurality, country of birth, Indigenous status, and homelessness, refugee status, cultural background and same-sex attraction and/or identification as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and/or asexual.

Qualitative thematic analysis of free-text responses, with the aid of the software program NVivo,33 will be undertaken to describe barriers and facilitators to access, use of digital technology in help seeking, young people’s understanding of the health system and the influences on their decisions to access which services when.

Expected outcomes

The primary outcomes will be self-report:

using yes/no responses to a list of known barriers (awareness of services; confidentiality, fear/embarrassment; negative experiences; physical barriers including cost, transport, availability of services, opening hours);

of barriers and facilitators using Likert scale responses.

To report frequencies with a 95% CI for non-marginalised young people and any group of marginalised young people, and to be able to detect minimum clinically and policy-relevant differences in primary outcomes between groups, we need approximately 350 respondents from each group. Our target sample size is 2100.

Consent and ethics

Completion of the survey will be deemed to be consent to participate. University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approval 2015/874; NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee approval 1142/15.

Study 2

Aim

To explore in depth the health service-related experiences of marginalised young people over time, to quantify contact with health services in real time and to describe inefficiencies or foregone care.

Design

Longitudinal, qualitative study using one-on-one semistructured interviews.

Participants

Young people who:

belong to one or more of the marginalised groups;

• have had contact with the health system in the previous 6 months which constitutes an index event.

The index event will be defined as: presentation to an emergency department, discharge from hospital, contact with a hospital outpatient or community-based health service for one or more of the following health conditions: mental health, drug and alcohol, sexual health, physical harm or injury, chronic medical illness or disability. Having an index event as an inclusion criterion will narrow the target population to include those young people likely to need or want ongoing contact with the health system over the study period, which will be important for studying system navigation.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited from the cross-sectional survey sample and selected on the basis of answers to identifier questions in the survey. We will recruit five to eight young people from each of the marginalised groups, noting that some young people belong to more than one of those groups.

Data collection

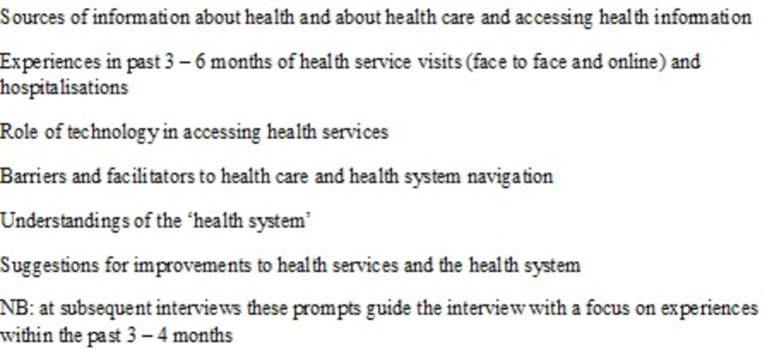

We will conduct three to four interviews over 6–12 months with each participant. These can be face-to-face, by telephone or Skype and will be audio-recorded and transcribed. Interpreters will be used if needed and, if desired, a parent/carer can be present for participants under 14. Data collection commenced in March 2016 and will continue until May/June 2017. The interview schedule includes questions about experiences of each contact with a health service as well as navigation through the health system over time (referral processes, communication between services, support for follow-up, understanding of the health system). The role of technology in making contact with services and moving around the health system will be explored. The ‘health system’ is defined broadly as any service delivering healthcare, including online services, general practice, emergency departments, allied health services, medical specialist services, pathology and imaging services, pharmacy services (eg, seeking advice from a pharmacist about medication), school counselling services, hospital outpatient services, hospital admissions and any other community or hospital-based services (youth health, mental health, headspace, drug and alcohol, sexual health, family planning, and so on). The interviews will be piloted among three to five youth consultants to ensure that questions are clear and the schedule flows logically. The interview schedule headings are listed in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Interview schedule headings for Study 2.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis will be descriptive and count frequencies such as number of encounters and number of services visited per participant over the study period. Interview transcripts will be entered into NVivo to assist with data coding; thematic analysis will be conducted to derive major and minor themes.

Expected outcomes

Number of service encounters and services accessed, referral patterns (including self-referral), foregone access due to a range of barriers, adherence to medications and follow-up care, experiences of health encounters and the young person’s perceptions about their health after each encounter. We will also describe areas of inefficiency in the system (such as duplication of services, multiple providers, long waiting times for specialist appointments, posthospital discharge care) as well as examples of integration, coordination and system efficiency.

Consent and ethics

Signed, written consent will be obtained from all participants prior to interviews. Parental consent was obtained for young people aged 12 and 13, in addition to consent from the young person. University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approval 2015/971; NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee approval 1141/15.

Study 3

Aim

To obtain the perspectives of professionals about how young people (12–24 years) in NSW access and navigate the health system.

Design

Qualitative cross-sectional study using one-on-one semistructured interviews.

Participants

Health service managers and experienced clinicians with in-depth knowledge about the health system and how it supports young people’s access to healthcare, who can provide key informant perspectives on health system navigation for 12 to 24-year-olds in NSW. The sampling frame is professionals from different sectors (health sector and non-government organisations) and different levels of the health system (primary, secondary, tertiary). A list of potential participants will be drawn from existing networks and contacts of the Access 3 study investigator and reference groups. Data collection commenced in June 2016 and will be completed by May 2017.

Recruitment

Direct approach by email.

Data collection

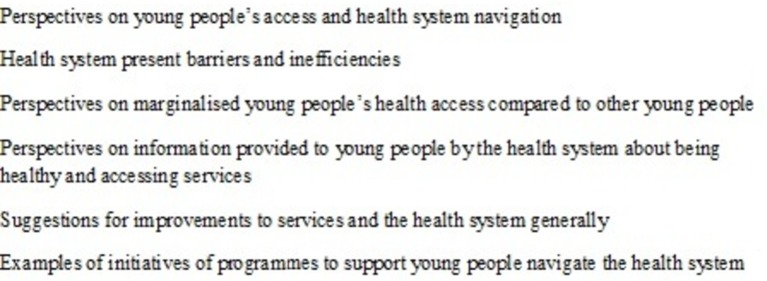

Face-to-face or telephone interviews which will be audio-recorded and transcribed. The interview schedule includes questions about barriers to care for young people, health system integration and coordination, and client-centred care. Content and themes derived from early young people interviews in Study 2 will be explored with the professionals where relevant or appropriate. Interviews were piloted among two to three Reference Group professional members to check for clarity and flow. Interview schedule headings are listed in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Interview schedule headings for Study 3.

Data analysis

Interview transcripts will be entered into NVivo to assist with data coding; content and thematic analysis will be conducted to derive major and minor themes.

Expected outcomes

Complementarity/triangulation of data from Study 2; contrasting perspectives between young people and professionals, practice or programme examples and recommendations that may inform policy.

Consent and ethics

Signed, written consent will be obtained from all participants prior to interviews. University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approval 2016/232; NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee approval 1175/16.

Study 4

Aim

To translate synthesised data from Studies 1, 2 and 3 into policy-ready recommendations.

Design

1-day facilitated workshop with stakeholders.

Participants

Young people, policy analysts, senior NSW Health staff, health managers, senior/expert clinicians, researchers, other key stakeholders (eg, community advocates).

Recruitment

Direct approach by email.

Data collection

Small group discussions/focus groups, recorded in writing. We will use a workshop framework informed by Lavis et al34 and Grimshaw22 Lavis et al developed a framework for knowledge transfer which asks five key questions: (1) What should be transferred? (2) To whom should research knowledge be transferred? (3) By whom should research knowledge be transferred? (4) How should research knowledge be transferred? (5) With what effect should research knowledge be transferred?

Grimshaw et al extend this framework to suggest that knowledge translation strategies need to consider likely barriers and facilitators to optimise their success. The workshop was held on 21 November 2016 and presented preliminary data analysis from Studies 1, 2 and 3. The NSW health department requested that the workshop be conducted before the end of the year, due to the need to inform the youth health policy framework. Representatives from the research team will continue to work with policy analysts on drafts and consultations of the youth health policy framework until it is finalised and approved by the NSW health department in the second half of 2017.

Data analysis

Content and thematic analysis of group discussions.

Expected outcomes

To provide NSW Health with concise policy recommendations for access to healthcare and health system navigation for youth health policy and advocacy.

Ethics

Not required.

Study timeline

The Access 3 study as a whole commenced in February 2016. Data collection for Study 1 was completed in March 2017, but is ongoing for the other components. The timeline for the Access 3 study is depicted below:

Stakeholder engagement

Three strategies underpin the study’s stakeholder engagement:

Involvement of young people

Youth participation35 has been sought in several ways. A Youth Consultant committee was convened for the life of the study to assist with design and piloting of instruments for Studies 1 and 2 and for promotion of the survey (Study 1). In addition, youth representation was sought on the study Reference Groups, and youth participants as key stakeholders at the policy translation workshop.

Structure of study governance and advisory teams

Due to its complexity, five groups were convened to manage and guide the study. The Chief Investigator team brings academic rigour and leadership to the research. An Associate Investigator team brings a combination of academic, project management and network expertise and will assist in some aspects of the research such as questionnaire and interview design/refinement, methods of recruitment, data analysis and dissemination. The Youth Consultant committee provides ongoing advice to all aspects of the study. Two Reference Groups (Metropolitan and Rural) have been convened to provide critical feedback on the study at different stages. This group consists of stakeholders who will be invited to comment on any aspects of the study but who may also be asked to assist with troubleshooting, engagement with participants and policy translation. Policymakers are included on the Reference Group.

Direct engagement with policymakers

Regular meetings have been scheduled over the study between representatives of the chief investigator team and senior policy analysts and managers in NSW Health and the NSW Youth Health Policy Reference Group.

Ethics and dissemination

Given the multifaceted design of this study, ethics approvals have been reported above following the description of the Methods and analysis section for each study component. In this study, we are exploring the health service access and navigation experiences of young people in a generation where technology is integrated into daily life. This will provide new evidence of national and international relevance for policymakers and practitioners charged with improving the health of young people. To answer our research questions, we are employing quantitative and qualitative research methods and have broad stakeholder and youth engagement an integral component of the design.

While we anticipate that this study will generate several important publications based on our findings, we also hope that this paper offers a protocol for a complex and large policy implementation initiative that will contribute to the translational research literature. Our design intends to address policy questions through robust research while embedding a way to maintain policy engagement.

The cross-sectional survey will provide for breadth of information gathering across the youth population in NSW and quantitative analysis of data. Online surveys promoted through social media have the potential for wide reach, which is essential in a relatively short time frame. The survey has identified potential participants for the longitudinal study, and survey data for those participants will act as a springboard for the initial interviews. The longitudinal study explores the young person’s journey through all parts of the health system, and allows an in-depth investigation into their navigation through the health system over time. There has been very little longitudinal research into health system navigation generally.

Our focus on subpopulations of marginalised young people is unique in its scope, since most research into marginalised groups of young people tends to focus on only one group. By targeting young people who are marginalised, we will also develop an understanding of how the health system supports those with complex needs and where there might be inefficiencies and gaps. This approach will enable comparison between groups and a better understanding of relative inequities in access to healthcare and variation in their use of technology for navigation of health services.

To understand structural issues and system inefficiencies more effectively, we are interviewing professionals and service managers, whose perspectives are also important in policy and practice translation. Key to our design therefore is the knowledge translation component of the study. To extend our academic interpretations of new knowledge, we will actively seek, document and translate our findings into policy and practice-relevant recommendations. While we have a knowledge translation study as part of the research design, we are incorporating knowledge translation theory22 into other aspects of the study by involving stakeholders in formal reference groups and through academic representation on the youth health policy advisory group. Feedback relating to new knowledge will be sought from the research team. Simultaneously, members of the research team will be involved in broader policy consultation. Together, these actions will provide substantial iterative processes to guide knowledge translation.

The main limitations of our study include the potential for recruitment bias due to our sampling strategies. Although we aim to oversample young people from five marginalised groups, we also want to include a broad cross section of young people living in NSW in the online survey. By recruiting participants through social media and stakeholder networks, we will have a convenience rather than a representative sample of young people in NSW. Our inclusion criteria for the longitudinal part of our study will not capture the full range of young people who are potentially marginalised.

In conclusion, a collaborative and participatory ethos underpins our design and research process. The study governance and support structure including young people and stakeholders will be assembled at the outset of the study and will guide all stages of the study. By explicitly examining the use of digital technology as an integrated process in health seeking and healthcare, we will generate novel empirical evidence about access to healthcare that will inform clinical practice, health service management and policymakers. Research outcomes can be used to focus policy and practice towards the alignment of structures and processes which can target and reduce inequalities in healthcare access. The ultimate objective is to improve health and well-being in vulnerable young people in NSW.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our youth consultants, associate investigators and reference group members for their active engagement and support of this study. We also thank Jessica Harper who provided assistance with ethics applications for Studies 1 and 2, technical help in developing the online survey and general research administration support.

Footnotes

Contributors: MK led the study design, wrote the tender for the grant, is the lead investigator and wrote the draft for the protocol manuscript. FR is the project manager responsible for day-to-day conduct of the study and contributed to the literature review of the manuscript. LS, KS, SJ, CH, MK and TU contributed to the study design, provided research leadership to the study and provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The Access 3 study is funded by NSW Health. Representatives from the funding body are members of the Project Reference Group. They have also been involved in planning the knowledge translation 1-day workshop to ensure that policy-relevant outcomes are achieved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. . Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016;387:2423–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2014. Australia’s health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra: AIHW. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanci L, Chondros P, Sawyer S, et al. . Responding to young people’s health risks in primary care: a cluster randomised trial of training clinicians in screening and motivational interviewing. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137581 10.1371/journal.pone.0137581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, et al. . Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet 2007;369:1481–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60370-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong LH, Chan FW, Wong FY, et al. . Transition care for adolescents and families with chronic illnesses. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:540–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Woods DM, Holl JL, Klein JD, et al. . Patient safety problems in adolescent medical care. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:5–12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation. Global standards for quality health-care services for adolescents: a guide to implement a standards-driven approach to improve the quality of health care services for adolescents. Volume 1: Standards and criteria. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/183935/1/9789241549332_vol1_eng.pdf (accessed 21 Dec 2016).

- 8. Hargreaves DS, Greaves F, Levay C, et al. . Comparison of health care experience and access between young and older adults in 11 high-income countries. J Adolesc Health 2015;57:413–20. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Veit FC, Sanci LA, Coffey CM, et al. . Barriers to effective primary health care for adolescents. Med J Aust 1996;165:131–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Booth ML, Bernard D, Quine S, et al. . Access to health care among Australian adolescents young people’s perspectives and their sociodemographic distribution. J Adolesc Health 2004;34:97–103. 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00304-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kang M, Bernard D, Usherwood T, et al. . Primary health care for young people: are there models of service delivery that improve access and quality? Youth Studies Australia 2006;25:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 12. NSW Department of Health, 2010, NSW Youth Health Policy 2011-2016. Healthy bodies, healthy minds, vibrant futures: NSW Department of Health, North Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tasmania Department of Health and Human Services. Youth Health Service Framework 2008-2011 Primary Health Services and Population Health. http://www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/30344/Youth_Health_Service_Framework_08-11.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2017).

- 14. National Mental Health Commission,. The National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Sydney: NMHC, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garling P. Final report of the special commission of inquiry acute care services in NSW public hospitals. State of NSW 2008;27. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freed GL, Gafforini S, Carson N. Age distribution of emergency department presentations in Victoria. Emerg Med Australas 2015;27:102–7. 10.1111/1742-6723.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sawyer SM, Proimos J, Towns SJ. Adolescent-friendly health services: what have children’s hospitals got to do with it? J Paediatr Child Health 2010;46:214–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01729.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). Aussie teens online: research snapshot. 1: ACMA, 2014. http://www.acma.gov.au/theACMA/engage-blogs/engage-blogs/Research-snapshots/Aussie-teens-online. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). Communications report 2013–14 series Report 1—Australians’ digital lives. ACMA, 2015. http://www.acma.gov.au/~/media/Research%20and%20Analysis/Research/pdf/Australians%20digital%20livesFinal%20pdf.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kauer SD, Mangan C, Sanci L. Do online mental health services improve help-seeking for young people? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e66 10.2196/jmir.3103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gold J, Pedrana AE, Stoove MA, et al. . Developing health promotion interventions on social networking sites: recommendations from the FaceSpace Project. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e30 10.2196/jmir.1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. . Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7:50 http://www.implementationscience.com/content/7/1/50 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dawson A, Jackson D. The primary health care service experiences and needs of homeless youth: a narrative synthesis of current evidence. Contemp Nurse 2013;44:62–75. 10.5172/conu.2013.44.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price M, Dalgleish J. Help-seeking among indigenous australian adolescents. Youth Studies Australia 2013;32:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colucci E, Minas H, Szwarc J, et al. . In or out? Barriers and facilitators to refugee-background young people accessing mental health services. Transcult Psychiatry 2015;52:766–90. 10.1177/1363461515571624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quine S, Bernard D, Booth M, et al. . Health and access issues among Australian adolescents: a rural-urban comparison. Rural Remote Health 2003;3 http://rrh.deakin.edu.au. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robinson KH, Bansel P, Denson N, et al. . Growing up Queer:issues Facing Young Australians who are gender variant and Sexuality Diverse. Melbourne: Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Booth M, Bernard D, Quine S, et al. . Access to health care among NSW adolescents: phase 1 Final Report. NSW Centre for the Advancement of Adolescent Health, the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, May 2002. ISBN: 0 95779 513 0. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kang M, Bernard D, Usherwood T, et al. . Better practice in Youth Health: final report on the research study Access to health care among young people in New South Wales: Phase 2. NSW CAAH in association with the Department of General Practice at Westmead Hospital. 2005. ISBN 0 97521 700 3. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chamberlain C, MacKenzie D. Australian Census Analytic Program: counting the homeless, 2006. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ambresin AE, Bennett K, Patton GC, et al. . Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people’s perspectives. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:670–81. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ibm CR. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bowen S, Zwi AB. Pathways to "evidence-informed" policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med 2005;2:e166 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, et al. . How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q 2003;81:221–48. 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre. Youth Involvement Guidelines. http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/141862/20160405-1343/www.youngandwellcrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/0_Young-and-Well-CRC-Youth-Involvement-Guidelines_150414_RM_v4.1.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.