Significance

Solving the Fokker–Planck equation for high-dimensional complex dynamical systems is an important issue. Effective strategies are developed and incorporated into efficient statistically accurate algorithms for solving the Fokker–Planck equations associated with a rich class of high-dimensional nonlinear turbulent dynamical systems with strong non-Gaussian features. These effective strategies exploit a judicious block decomposition of high-dimensional conditional covariance matrices and statistical symmetry to facilitate an extremely efficient parallel computation and a significant reduction of sample numbers. The resulting algorithms can efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation in much higher dimensions even with orders in the millions and thus beat the curse of dimension. Skillful behavior of the algorithms is illustrated for highly non-Gaussian systems in excitable media and geophysical turbulence.

Keywords: high-dimensional non-Gaussian PDFs, hybrid strategy, block decomposition, statistical symmetry, small sample size

Abstract

Solving the Fokker–Planck equation for high-dimensional complex dynamical systems is an important issue. Recently, the authors developed efficient statistically accurate algorithms for solving the Fokker–Planck equations associated with high-dimensional nonlinear turbulent dynamical systems with conditional Gaussian structures, which contain many strong non-Gaussian features such as intermittency and fat-tailed probability density functions (PDFs). The algorithms involve a hybrid strategy with a small number of samples , where a conditional Gaussian mixture in a high-dimensional subspace via an extremely efficient parametric method is combined with a judicious Gaussian kernel density estimation in the remaining low-dimensional subspace. In this article, two effective strategies are developed and incorporated into these algorithms. The first strategy involves a judicious block decomposition of the conditional covariance matrix such that the evolutions of different blocks have no interactions, which allows an extremely efficient parallel computation due to the small size of each individual block. The second strategy exploits statistical symmetry for a further reduction of . The resulting algorithms can efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation with strongly non-Gaussian PDFs in much higher dimensions even with orders in the millions and thus beat the curse of dimension. The algorithms are applied to a -dimensional stochastic coupled FitzHugh–Nagumo model for excitable media. An accurate recovery of both the transient and equilibrium non-Gaussian PDFs requires only samples! In addition, the block decomposition facilitates the algorithms to efficiently capture the distinct non-Gaussian features at different locations in a -dimensional two-layer inhomogeneous Lorenz 96 model, using only samples.

The Fokker–Planck equation is a partial differential equation (PDE) that governs the time evolution of the probability density function (PDF) of a complex system with noise (1, 2). For a general nonlinear dynamical system,

| [1] |

with state variables , noise matrix , and white noise , the associated Fokker–Planck equation is given by

| [2] |

with . In many complex dynamical systems, such as geophysical and engineering turbulence, neuroscience, and excitable media, the solution of the Fokker–Planck equation in Eq. 2 involves strong non-Gaussian features with intermittency and extreme events (3–5). In addition, the dimension of in these complex systems is typically very large, representing a variety of variability in different temporal and spatial scales (3, 6). Therefore, solving the high-dimensional Fokker–Planck equation for both the steady-state and transient phases with non-Gaussian features is an important issue. However, traditional numerical methods such as finite element and finite difference as well as the direct Monte Carlo simulations of Eq. 1 all suffer from the curse of dimension (7, 8).

Recently, the authors developed efficient statistically accurate algorithms for solving the Fokker–Planck equation associated with high-dimensional nonlinear turbulent dynamical systems with conditional Gaussian structures (9). These conditional Gaussian nonlinear dynamical systems capture many strong non-Gaussian features such as intermittency and fat-tailed PDFs (10). Applications of the conditional Gaussian framework include modeling and predicting the highly intermittent time series of the Madden–Julian oscillation and monsoon (11–13), state estimation of the turbulent ocean flows from noisy Lagrangian tracers (14–16), dynamic stochastic superresolution of sparsely observed turbulent systems (17), and stochastic superparameterization for geophysical turbulent flows (18), etc. The efficient statistically accurate algorithms in ref. 9 involve a hybrid strategy that requires only a small number of samples. In these algorithms, a conditional Gaussian mixture in the high-dimensional subspace of via an extremely efficient parametric method is combined with a judicious Gaussian kernel density estimation in the remaining low-dimensional subspace of . Particularly, the parametric method provides closed analytical formulas for determining the conditional Gaussian distributions in the high-dimensional subspace of and is therefore computationally efficient and accurate. It has been shown in a stringent set of numerical tests (9) that with an order of samples the mixture distribution has significant skill in capturing both the statistically steady state and the transient behavior with fat tails of non-Gaussian PDFs in up to six dimensions. Rigorous analysis (19) indicates that does not increase exponentially as the dimension of the high-dimensional subspace of to maintain a given level of accuracy, which is fundamentally different from Monte Carlo methods.

In this article, two effective strategies are developed and incorporated into the algorithms in ref. 9 (hereafter, basic algorithms) that enable the expanded algorithms to efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation in much higher dimensions, even with orders in the millions. In fact, the major computational cost in the basic algorithms for systems with a large dimension of state variables comes from solving the time evolution of the conditional covariance. To overcome this difficulty, an effective strategy involving a decomposition of the state variables into different groups with each is developed. Then the high-dimensional conditional covariance matrix of conditioned on becomes a block diagonal matrix under the conditions that the nonlinear terms on the right-hand side of in Eq. 1 consist of any nonlinear interactions between different components of but only those between and nonlinear functions of . Note that such conditions are not artificial and they are actually salient features of many complex dynamical systems with multiscale structures (18), multilevel dynamics (20), or state-dependent parameterizations (17). One important characteristic of the resulting covariance matrix is that the evolution of the th block, representing the conditional covariance of conditioned on , has no interactions with that of for all . This allows an extremely efficient parallel computation due to the small size of each individual block. On the other hand, the conditional means of different are all coupled in their evolutions.

The second effective strategy exploits the statistical symmetry if the dynamical system in Eq. 1 is statistically homogeneous; namely, the statistics of different are identical with each other. The statistical symmetry is often satisfied when the underlying dynamics in Eq. 1 represent a discrete approximation of some PDEs in a periodic domain with nonlinear advection, diffusion, and homogeneous external forcing. Examples include a rich class of models in geophysical turbulence and excitable media (4, 21). In light of statistical symmetry, the number of samples in the algorithms can be greatly reduced. In fact, the effective sample size of each becomes and therefore a much smaller is needed to reach the same level of accuracy as in the situation without using statistical symmetry.

These effective strategies are incorporated into the basic algorithms and then applied to two highly non-Gaussian dynamical systems. The first model is a -dimensional stochastic coupled FitzHugh–Nagumo (FHN) model for excitable media with extreme events (4, 22). It describes activation and deactivation dynamics of spiking neurons and has scale-invariant features. The block decomposition leads to solving the evolution of individual covariance matrices and the statistical symmetry allows an accurate estimation of both the transient and the steady-state PDFs using only samples! The second model is the so-called two-layer Lorenz 96 (L96) model in geophysical turbulence (20, 23, 24), which is widely used as a testbed for data assimilation and parameterization in numerical weather forecasting. Inhomogeneous damping and coupling are adopted in the model with state variables that mimic the atmosphere motion along a latitude circle with different dissipation over land and sea. Despite the absence of statistical symmetry, the block decomposition facilitates the algorithms to efficiently capture the distinct non-Gaussian features at different locations, using only samples.

The remainder of this article includes a detailed description of these effective strategies and their application to the stochastic coupled FHN and two-layer L96 models in solving the highly non-Gaussian PDFs at both the transient and statistical equilibrium phases, using a small number of samples.

Algorithms

Conditional Gaussian Framework.

The general framework of conditional Gaussian models is given as (10, 25)

| [3a] |

| [3b] |

where with both and being multidimensional state variables. In Eq. 3, and are vectors and matrices that depend only on time and the state variables , and and are independent Wiener processes. The systems in Eq. 3 are named as conditional Gaussian systems due to the fact that once for is given, conditioned on becomes a Gaussian process with mean and covariance ; i.e.,

| [4] |

Despite the conditional Gaussianity, the coupled system in Eq. 3 remains highly nonlinear and is able to capture many non-Gaussian features as observed in nature (10). One of the desirable features of Eq. 3 is that the conditional distribution in Eq. 4 has the following closed analytical form (25):

| [5a] |

| [5b] |

Basic Algorithms.

Here, we summarize the basic efficient statistically accurate algorithms developed in ref. 9. First, we generate independent trajectories of the variables , namely . Then, different strategies are used to deal with and . The PDF of is estimated via a parametric method that exploits the closed form of the conditional Gaussian statistics in Eq. 5,

| [6] |

Note that the limit in Eq. 6 (as well as Eqs. 7 and 8 below) is taken to illustrate the statistical intuition, while the estimator is the nonasymptotic version. On the other hand, a Gaussian kernel density estimation method is used for solving the PDF of the observed variables ,

| [7] |

where is a Gaussian kernel centered at each sample point with covariance given by the bandwidth matrix . The kernel density estimation algorithm here involves a “solve-the-equation plug-in” approach for optimizing the bandwidth (26) that works for any non-Gaussian PDFs. Finally, combining Eqs. 6 and 7, a hybrid method is applied to solve the joint PDF of and through a Gaussian mixture,

| [8] |

Practically, is sufficient for the hybrid method to solve the joint PDF with and . Since is small, the trajectories can be obtained by running a Monte Carlo simulation for the coupled system [3], which is computationally affordable. In addition, the closed form of the conditional distributions in Eq. 6 can be solved in a parallel way due to their independence (9), which further reduces the computational cost.

Beating the Curse of Dimension with Block Decomposition.

The basic algorithms succeed in solving the Fokker–Planck equation with state variables. Now we develop an effective strategy with block decomposition and incorporate it into the basic algorithms. The expanded algorithms can efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation in much higher dimensions even with orders in the millions and beat the curse of dimension.

Consider the following decomposition of state variables

where , , and . Correspondingly, the full dynamics in Eq. 3 are also decomposed into groups, where the variables on the left-hand side of the th group are . In addition, we assume both and are diagonal for notation simplicity.

To develop efficient statistically accurate algorithms that beat the curse of dimension, the following two conditions are imposed on the coupled system:

Condition 1:

In the dynamics of each in Eq. 3, the terms and can depend on all of the components of while the terms and are only functions of ; namely,

| [9] |

In addition, only interacts with and on the right-hand side of the dynamics of .

Condition 2:

The initial values of and with are independent from each other.

Conditions 1 and 2 are not artificial and they are actually the salient features of many complex systems with multiscale structures (18), multilevel dynamics (20), or state-dependent parameterizations (17). Under these two conditions, the conditional covariance matrix becomes block diagonal, which can be easily verified according to Eq. 5b. The evolution of the conditional covariance of conditioned on is given by

which has no interaction with that of for all since and do not enter into the evolution of the conditional covariance. Notably, the evolutions of different with can be solved in a parallel way and the computation is extremely efficient due to the small size of each individual block. This facilitates the algorithms to efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation in large dimensions.

Next, the structures of and in Eq. 9 allow the coupling among all of the groups of variables in the conditional mean according to Eq. 5a. The evolution of , namely the conditional mean of conditioned on , is given by

Statistical Symmetry.

The computational cost in the algorithms developed above can be further reduced if the coupled system Eq. 3 has statistical symmetry; namely,

including the initial conditions. The statistical symmetry is often satisfied when the underlying dynamical system represents a discrete approximation of some PDEs in a periodic domain with nonlinear advection, diffusion, and homogeneous external forcing (21, 27).

With the statistical symmetry, collecting the conditional Gaussian ensembles for a specific in different simulations is equivalent to collecting that for all with in a single simulation. This also applies to that are associated with . Therefore, the statistical symmetry implies that the effective sample size is , where is the number of the group variables that are statistically symmetric and is the number of different simulations of the coupled systems via Monte Carlo. If is large, then a much smaller is needed to reach the same accuracy as in the situation without using statistical symmetry, which greatly reduces the computational cost. SI Appendix provides the mathematical details of reconstructing the joint PDFs, using statistical symmetry.

A Stochastic Coupled FHN Model

The efficient statistically accurate algorithms developed in this article work for a wide class of models in excitable media (4), including different versions of the famous FHN model that describes activation and deactivation dynamics of spiking neurons. Here, the algorithms are applied to a stochastic coupled FHN model with elements (4, 22),

| [10a] |

| [10b] |

where and are activator and inhibitor variables and they belong to and in the conditional Gaussian framework, respectively, such that the conditions of the block decomposition strategy are satisfied. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed on variables. In Eq. 10, the timescale ratio leads to a slow–fast structure of the model. The parameter such that the system has a global attractor in the absence of noise and diffusion (28). The random noise is able to drive the system above the threshold level of global stability and triggers limit cycles intermittently. Note that with , the model reduces to the classical FHN model with a single neuron and it contains the model families with both coherence resonance and self-induced stochastic resonance (29). With different choices of the noise strength and the diffusion coefficient , the system in Eq. 10 exhibits rich dynamical behaviors. Below, we adopt constant parameters and the initial values are for all . Therefore, the model satisfies the statistical symmetry.

Model Behavior in Different Dynamical Regimes.

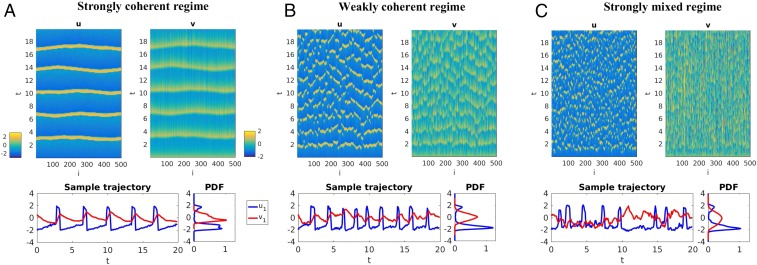

Fig. 1 shows the model behavior in three different regimes with . Here, the noise coefficient is fixed while different values of and are chosen for the three regimes. In Fig. 1A, the spatial–temporal patterns are highly coherent due to the choice of a weak noise and a strong diffusion . The time series of both and have nearly regular oscillations with large bursts in around every units. The associated statistical equilibrium PDF of is bimodal while that of is skewed. With an increase of the noise and a decrease of the diffusion (Fig. 1B), the coherent patterns becomes much weaker and only quasi-regular periods are found in the time series of . The associated PDF of turns into symmetric and slightly sub-Gaussian. With a further increase of the noise to (Fig. 1C), the spatial–temporal pattern becomes strongly mixed and the time series is more irregular. Correspondingly, the PDF of becomes nearly Gaussian with a large variance.

Fig. 1.

Stochastic coupled FHN model. Shown are three dynamical regimes of the stochastic coupled FHN model in Eq. 10. (A) Strongly coherent regime with and . (B) Weakly coherent regime with and . (C) Strongly mixed regime with and . Each plot shows the spatial–temporal evolutions of and (A–C, Top) as well as the time series and equilibrium PDFs at (A–C, Bottom). Due to the homogeneous property, the PDFs at different grid points are the same.

It is shown in SI Appendix that the FHN model Eq. 10 is scale invariant in all three regimes. The scale-invariant structure means that the spatial–temporal structures in any given scale change little as the number of spatial grid points increases. Mutual information (30) is used to quantify the dependence of different variables with strongly non-Gaussian features, the advantage of which over pattern correlation is also clearly illustrated in SI Appendix.

Recovering the PDFs at Both Transient and Equilibrium Phases Exploiting Statistical Symmetry.

Now we apply the efficient statistically accurate algorithms to solve the PDFs associated with the stochastic coupled FHN system in Eq. 10. Here we focus on the weakly coherent regime (Fig. 1B). Due to the statistical symmetry, the effective sample size is , where is the number of repeated simulations of the systems. Below, we simply take in the efficient statistically accurate algorithms, which is extremely cheap. For comparison, we take in Monte Carlo simulations and again use statistical symmetry to generate the true PDFs and therefore the effective sample size in Monte Carlo simulation is = 150,000.

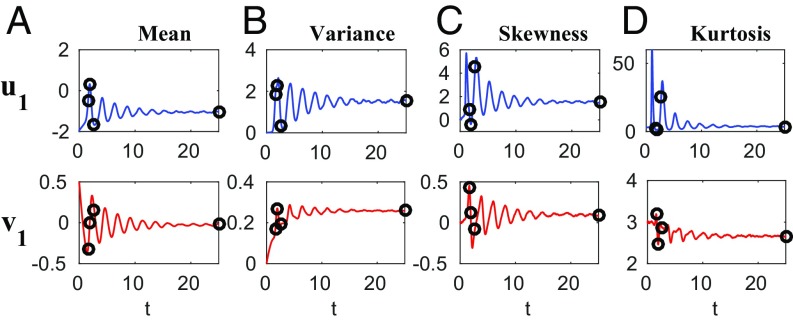

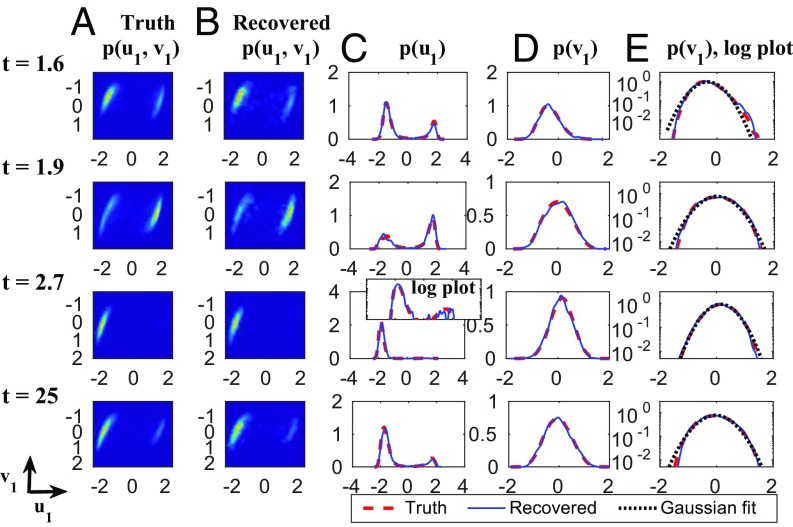

The time evolutions of the first four moments associated with and are shown in Fig. 2, where the black circles mark three transient phases and the statistical equilibrium phase with different non-Gaussian features. Fig. 3 shows the skill of solving the one-point statistics at these phases. First, the PDFs of at and with different bimodal features are all accurately recovered. Next, at has a tiny second peak around since only about of the events at this time instant have large bursts and these rare events contribute to a significant kurtosis of at . Nevertheless, the efficient statistically accurate algorithm succeeds in capturing the appearance of this weak peak and the recovered PDF almost overlaps with the truth. On the other hand, the skewed at and the sub-Gaussian at , and are all recovered with high accuracy by the algorithm. In addition, the recovered joint PDFs at different phases all resemble the truth.

Fig. 2.

Stochastic coupled FHN model. Shown is time evolution of 1D marginal statistics associated with and . Due to the homogeneous property, these statistics at different grid points remain the same. The black circles in A–D mark the time instants that the recovered PDFs from the efficient statistically accurate algorithms are compared with the truth in Figs. 3 and 4. At the statistical equilibrium phase, the skewness and kurtosis of are and , respectively.

Fig. 3.

Stochastic coupled FHN model. Shown is a comparison of the truth and recovered PDFs at three transient phases , and as well as the statistical equilibrium phase . A and B show the truth and recovered 2D PDF . C and D compare the recovered 1D PDFs and (blue) with the truth (red). E shows the logarithm plots of D, where the black dotted curves are the Gaussian fits of the truth. Inset above the subplot of at in C is also in logarithm scale, ranging from to .

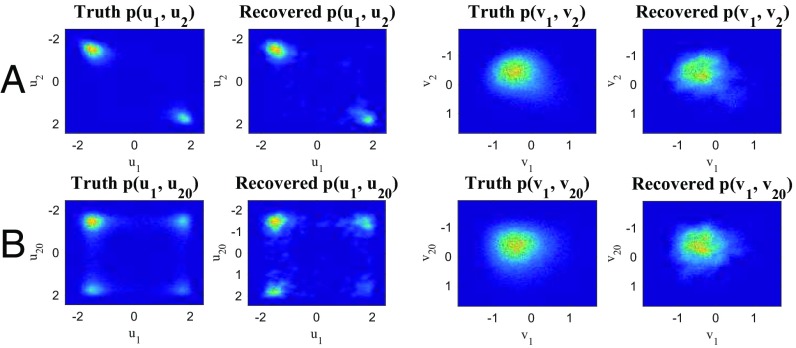

Fig. 4 illustrates the recovered two-point statistics at . Fig. 4 A and B shows the PDFs and and those for , respectively. The variables and have a strong correlation while and are nearly uncorrelated. These features as well as the highly non-Gaussian PDFs with multiple peaks are both captured by the recovered PDFs from the efficient statistically accurate algorithms with only . Likewise, the skewed and nearly Gaussian joint PDFs and are also recovered with high accuracy.

Fig. 4.

Stochastic coupled FHN model. Shown is a comparison of the 2D PDFs with components from two different grid points at . Rows A and B show the truth and the recovered (A) and (B), respectively.

Two-Layer Inhomogeneous L96 Model

The two-layer L96 model is a conceptual model in geophysical turbulence that is widely used as a testbed for data assimilation and parameterization in numerical weather forecasting (20, 23, 24). The model can be regarded as a coarse discretization of atmospheric flow on a latitude circle with complicated wave-like and chaotic behavior. It schematically describes the interaction between small-scale fluctuations with larger-scale motions. In the model presented here, large-scale motions are denoted by variables , which are coupled to small-scale variables ,

| [11a] |

| [11b] |

with periodic boundary conditions in . One important feature of Eq. 11 is that the nonlinear interaction between and conserves energy, as observed in nature (3). The two-layer L96 model belongs to the conditional Gaussian framework in Eq. 3 with and . Below, we take as in the standard L96 model. Associated with each , there are variables representing different scales of fluctuations. Thus, the total number of state variables is . A constant forcing is adopted in Eq. 11a while both the damping and the coupling are functions in space. Therefore, the model is inhomogeneous. These mimic the situation that the damping and coupling above the ocean are weaker than those above the land since the latter usually have stronger friction or dissipation. As a result, the large-scale wave patterns over the ocean are more significant (Fig. 5). The model in Eq. 11 has many desirable properties as in more complicated turbulent systems. Particularly, the smaller scales are more intermittent with stronger fat tails in PDFs. See SI Appendix for more details.

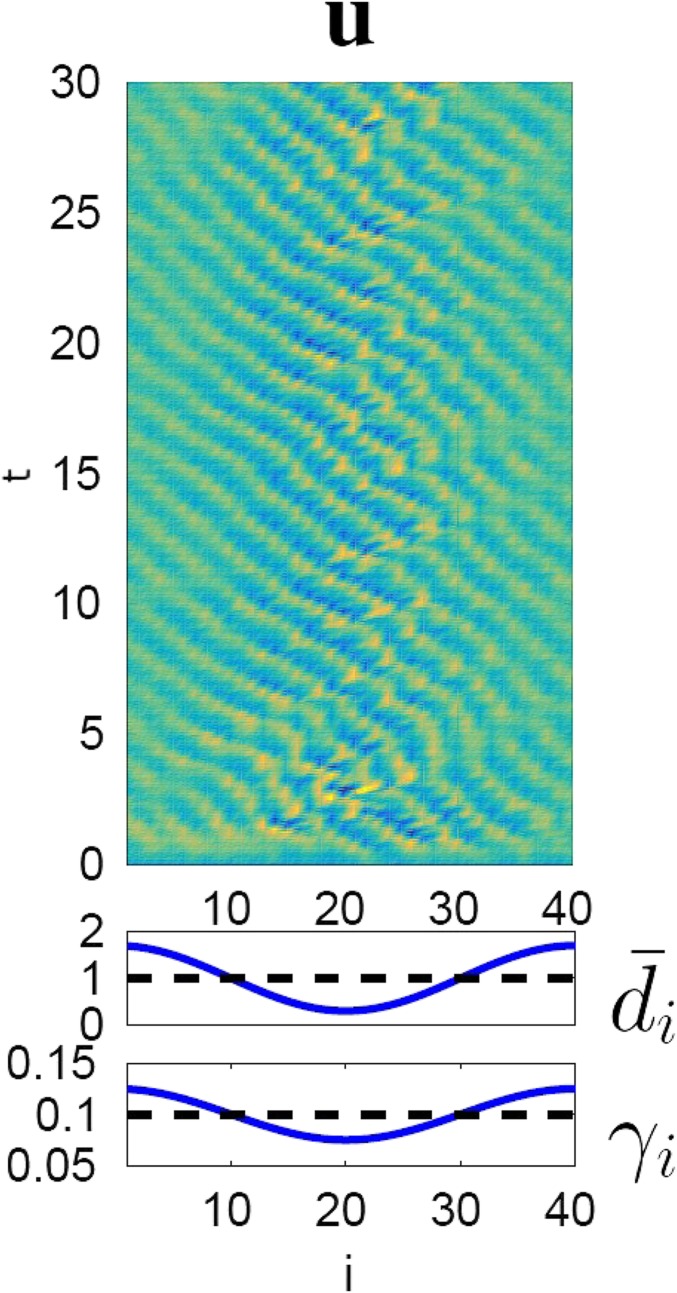

Fig. 5.

Spatial–temporal evolution of the observed variables in the two-layer L-96 model Eq. 11 with . The profiles of damping and coupling coefficients as a function of are shown below the spatial–temporal evolution of in solid blue curves and the black dashed lines represent the spatial averaged values. Here, and .

Although the two-layer inhomogeneous L96 model in Eq. 11 has no statistical symmetry, the model structure nevertheless allows the effective block decomposition. Below, trajectories of each variable are simulated from Eq. 11 to implement the efficient statistically accurate algorithms. As a comparison, a direct Monte Carlo method requires = 150,000 samples for each of the variables for an accurate estimation of at least the one-point statistics. This means the total number of samples is around ! For an efficient calculation of the truth, we focus only on the statistical equilibrium state here but the algorithms are not restricted to the equilibrium statistics. The true PDFs are calculated using the Monte Carlo samples over a long time series in light of the ergodicity while the recovered PDFs from the efficient statistically accurate algorithms are computed at .

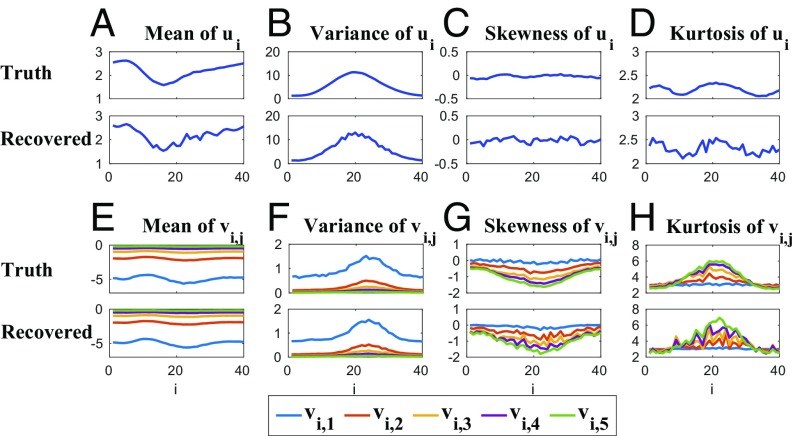

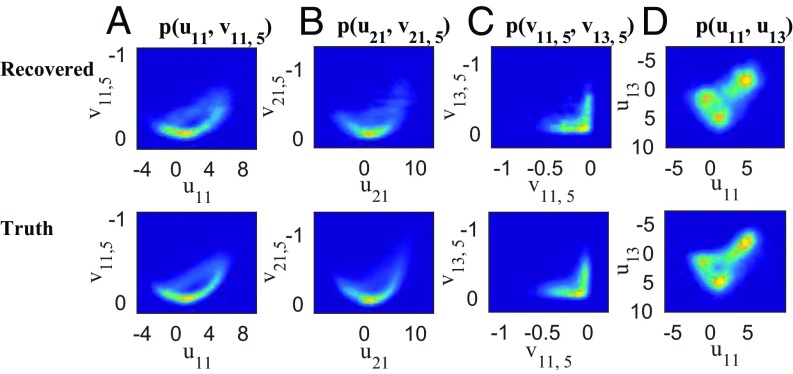

Fig. 6 shows the one-point statistics as a function of regarding the first four moments of and each . The mean and variance resulting from the efficient statistically accurate algorithms of all variables are highly consistent with the truth. For the skewness and kurtosis, despite small fluctuations in the recovered statistics, the pattern correlations between the curves associated with the truth and the recovered statistics are significant unless both are nearly flat (SI Appendix). These results indicate the success of the efficient statistically accurate algorithms in capturing the inhomogeneous behavior of the model. Fig. 7 demonstrates the skill of recovering different 2D joint PDFs. Fig. 7 A and B shows the PDFs at and . These highly non-Gaussian PDFs with distinct features are recovered accurately by the algorithms. On the other hand, Fig. 7C shows the joint PDFs of the two smallest-scale fluctuation variables and , which are highly correlated and have strong non-Gaussian features. Fig. 7D shows the joint PDFs , where the two components also have a strong correlation. The efficient statistically accurate algorithms succeed in solving all these joint PDFs with only samples.

Fig. 6.

Two-layer inhomogeneous L-96 model. (A–D) Comparison of the truth and the recovered mean, variance, skewness, and kurtosis of for = 1,…,5 as a function of i. (E–H) The same but for .

Fig. 7.

Two-layer inhomogeneous L-96 model. (A–D) Comparison of 2D joint PDFs at a fixed grid point (A and B) and between two different grid points (C and D).

Concluding Discussion

Effective strategies involving block decomposition of the conditional covariance matrix and statistical symmetry are developed and incorporated into the efficient statistically accurate algorithms in ref. 9. The resulting expanded algorithms are able to efficiently solve the Fokker–Planck equation in much higher dimensions even with orders in the millions and thus beat the curse of dimension. Applications of these effective strategies to both the stochastic coupled FHN and the two-layer inhomogeneous L96 models illustrate the efficiency and accuracy.

It is worthwhile pointing out that although only the recovered one-point and two-point statistics are shown in this article for illustration purposes, the algorithms can actually provide an accurate estimation of the full joint PDF of , using a small number of samples. This is because the sample size in these algorithms does not grow exponentially as the dimension of , which is fundamentally different from Monte Carlo methods. See ref. 19 for a theoretical justification. The algorithms developed here are extremely useful in understanding the causality as well as improving the parameterizations and predictions of high-dimensional complex turbulent dynamical systems with non-Gaussian features.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research of A.J.M. is partially supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) Grant N0001416-1-2161 and the New York University Abu Dhabi Research Institute. N.C. is supported as a postdoctoral fellow through A.J.M.’s ONR MURI Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1717017114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gardiner CW. Stochastic Methods. Springer; Berlin: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Risken H. 1989. The Fokker-Planck equation. Methods of Solution and Applications, Springer Series in Synergetics, ed Haken H (Springer, Berlin), Vol 18.

- 3.Majda A. 2016. Introduction to Turbulent Dynamical Systems in Complex Systems, Frontiers in Applied Dynamical Systems: Reviews and Tutorials 5 (Springer, Cham, Switzerland)

- 4.Lindner B, Garcıa-Ojalvo J, Neiman A, Schimansky-Geier L. Effects of noise in excitable systems. Phys Rep. 2004;392:321–424. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cousins W, Sapsis TP. Reduced-order precursors of rare events in unidirectional nonlinear water waves. J Fluid Mech. 2016;790:368–388. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vallis GK. Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichler L, Masud A, Bergman LA. Numerical solution of the Fokker–Planck equation by finite difference and finite element methods – A comparative study. In: Papadrakakis M, Stefanou G, Papadopoulos V, editors. Computational Methods in Stochastic Dynamics. Springer, Dordrecht; The Netherlands: 2013. pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robert CP. Monte Carlo Methods. Wiley, Hoboken; NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen N, Majda AJ. Efficient statistically accurate algorithms for solving Fokker-Planck equations in large dimensions. J Comput Phys. October 23, 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2017.10.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Majda AJ. Filtering nonlinear turbulent dynamical systems through conditional Gaussian statistics. Monthly Weather Rev. 2016;144:4885–4917. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen N, Majda AJ, Giannakis D. Predicting the cloud patterns of the Madden-Julian oscillation through a low-order nonlinear stochastic model. Geophys Res Lett. 2014;41:5612–5619. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen N, Majda AJ. Predicting the real-time multivariate Madden–Julian oscillation index through a low-order nonlinear stochastic model. Monthly Weather Rev. 2015;143:2148–2169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen N, Majda AJ. Predicting the cloud patterns for the boreal summer intraseasonal oscillation through a low-order stochastic model. Math Clim Weather Forecast. 2015;1:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen N, Majda AJ, Tong XT. Information barriers for noisy Lagrangian tracers in filtering random incompressible flows. Nonlinearity. 2014;27:2133–2163. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen N, Majda AJ, Tong XT. Noisy Lagrangian tracers for filtering random rotating compressible flows. J Nonlinear Sci. 2015;25:451–488. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen N, Majda AJ. Model error in filtering random compressible flows utilizing noisy Lagrangian tracers. Mon Weather Rev. 2016;144:4037–4061. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branicki M, Majda AJ. Dynamic stochastic superresolution of sparsely observed turbulent systems. J Comput Phys. 2013;241:333–363. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majda AJ, Grooms I. New perspectives on superparameterization for geophysical turbulence. J Comput Phys. 2014;271:60–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen N, Majda AJ, Tong XT. Rigorous analysis for efficient statistically accurate algorithms for solving Fokker-Planck equations in large dimensions. SIAM/ASA J Uncertain Quantif. 2017 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilks DS. Effects of stochastic parametrizations in the lorenz’96 system. Q J R Meteorol Soc. 2005;131:389–407. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majda A, Wang X. Nonlinear Dynamics and Statistical Theories for Basic Geophysical Flows. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muratov CB, Vanden-Eijnden E, Weinan E. Noise can play an organizing role for the recurrent dynamics in excitable media. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:702–707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607433104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee Y, Majda AJ. Multiscale data assimilation and prediction using clustered particle filters. J Comput Phys. 2017 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold H, Moroz I, Palmer T. Stochastic parametrizations and model uncertainty in the lorenz’96 system. Philos Trans R Soc A. 2013;371:20110479. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2011.0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liptser RS, Shiryaev AN. Statistics of Random Processes II: II. Applications. Vol 2 Springer; Berlin: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botev ZI, et al. Kernel density estimation via diffusion. Ann Stat. 2010;38:2916–2957. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majda AJ, Harlim J. Filtering Complex Turbulent Systems. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guckenheimer J, Holmes PJ. Nonlinear Oscillations, Dynamical Systems, and Bifurcations of Vector Fields. Vol 42 Springer; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeVille RL, Vanden-Eijnden E, Muratov CB. Two distinct mechanisms of coherence in randomly perturbed dynamical systems. Phys Rev E. 2005;72:031105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.031105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branicki M, Majda A. Quantifying Bayesian filter performance for turbulent dynamical systems through information theory. Commun Math Sci. 2014;12:901–978. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.