Abstract

Melasma is one of the most common hyperpigmentary disorders found mainly in women and dark-skinned patients. Sunlight, hormones, pregnancy, and genetics remain the most implicated in the causation of melasma. Although rather recalcitrant to treatment, topical agents such as hydroquinone, modified Kligman's Regime, azelaic acid, kojic acid, Vitamin C, and arbutin still remain the mainstay of therapy with sun protection being a cornerstone of therapy. There are several new botanical and non botanical agents and upcoming oral therapies for the future. There is a lack of therapeutic guidelines, more so in the Indian setup. The article discusses available evidence and brings forward a suggested treatment algorithm by experts from Pigmentary Disorders Society (PDS) in a collaborative discussion called South Asian Pigmentary Forum (SPF).

Keywords: Expert group, medical treatment, melasma

What was known?

Medical management of melasma with topical hydroquinone or triple combination cream is the most effective treatment of melasma, although the last decade or more has seen a lot of side effects due to corticosteroids or hydroquinone if used unsupervised in Indian patients.

Azelaic acid and kojic acid and vitamic C topically, though weaker gaents, offer an alternative to hydroquinone containing creams.

An initial evaluation and treatment of medical factors, photoprotection and triple combination cream works well and should be rotated with other non hydroquinone containing agents.

Introduction

Melasma is a common acquired pigmentary skin disorder characterized by a symmetrical macular pigmentation of sun-exposed areas like the face. The three major patterns of pigmentation in melasma are centrofacial (cheeks, forehead, upper lip, and nose), malar (cheeks and nose), and mandibular (mandibular area of cheeks). Melasma affects females much more commonly than males and majority of patients are in the third and fourth decades of their life. Several factors such as genetics, sunlight, cosmetics, pregnancy, hormonal treatments, thyroid dysfunction, and drugs have been implicated in the pathogenesis of melasma.

The treatment of melasma includes various topical and/or systemic agents. The aim of this article is to review the evidence available from the existing literature on prevalence and predisposing factors of melasma and suggest management guidelines for this common yet challenging skin disorder. This article discusses available evidence and brings forward a suggested treatment algorithm by 15 experts from Pigmentary Disorders Society (PDS) in a collaborative discussion called South Asian Pigmentary Disorders Forum (SPF).

Methods

A panel comprising of 15 eminent dermatologists form across the country with vast experience and significant academic contribution toward melasma was formed. These were experts from Pigmentary Disorders Society (PDS) in a collaborative effort called South Asian Pigmentary Disorders Forum (SPF).

This was followed by an extensive literature search from the database-PUBMED and COCHRANE LIBRARY. The keywords used for the search were melasma, treatment, management, hydroquinone (HQ), retinoids, sunscreens, oral drugs, safety, triple combination, chemical peels, and lasers. The articles published in the past two decades were included in the study. However, few older publications were included to describe the evolution of treatment over the years. Poorly designed studies and those with conflicting results were excluded from the study. This was followed by day panel discussion during which the opinion of the panellists was sought and recorded.

Findings

Prevalence and predisposing factors

The reported prevalence of melasma is variable and is based on the population group studied. It ranges from 8.8% among Latino males to 40% in Southeast Asian populations.[1] In a prospective study conducted by Sarkar et al. in a tertiary care hospital in India, the prevalence of melasma was found to be 20.5% in men.[2] Melasma, however, affects women more commonly than men.[2]

The major etiological factors involved in melasma are genetic susceptibility, sun exposure, and hormones. Ortonne et al. conducted a larger global survey in 324 women with melasma and found that 50% of patients had a family history of melasma in at least one family member. The most common time of onset of melasma was post pregnancy (42%), whereas 26% of patients developed it during pregnancy.[3] In another study carried out by Tamega Ade et al. in 302 Brazilian patients with melasma, it was found that the most common precipitating factors were pregnancy (36.4%), oral contraceptives (16.2%), and sun exposure (27.2%).[4]

The frequency of thyroid disorders is four times greater in patients with melasma,[5] In a study conducted by Lutfi et al., thyroid abnormalities were found in 58.3% of melasma patients.[5] In a recent Indian study conducted by Gopichandani et al. in melasma patients, levels of lueienizing hormone, estradiol, and progesterone were lower in cases compared to controls indicating a suppression of hypothalamic-gonadal axis in these patients. Other factors that could contribute include: estrogens such as estriol and estrone, overexpression of estrogen receptors or increased responsiveness to circulating estrogens. The study also found low testosterone in patients as compared to the control group, again pointing toward a suppressed gonadal function.[6]

Important/key points

There is a paucity of community-based studies documenting the prevalence of melasma. Majority of currently available literature and statistics are from hospital-based studies

Sun exposure and hormonal stimuli in a genetically predisposed individual can lead to the development of melasma

More studies needed to validate the association between hormones and melasma.

Sunprotection for melasma

There is sufficient literature to prove that light from both ultraviolet (UV) and visible spectrum is involved in the pathogenesis of melasma. To assess the efficacy of sunscreens in preventing the development of melasma, Lakhdar et al. conducted a study in 200 Moroccan females who were <3 months pregnant. They were asked to use a sunscreen with Sun Protection Factor (SPF) of 50+ and UVA protection factor of 28 during the day, and it was seen that only 2.7% of these women developed melasma during pregnancy.[7]

Boukari et al. in a prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT), conducted in 40 patients with melasma, established the efficacy of sunscreen with combined protection against UV and short wavelengths of visible light (VL) in preventing melasma relapses.[8] Both the treatment groups contained the same filters against UV except that one group received formula containing iron oxides (Visible light absorbing pigment) also. The other group had a significant increase in melasma area severity index (MASI) from baseline to month 6, as compared to the one having the additional iron oxide, hence emphasizing the role of VL in the pathogenesis of melasma.

This was further confirmed in a study by Castanedo-Cazares et al. in a double-blind RCT in 68 patients with melasma to assess the efficacy of sunscreen with broad-spectrum UV protection containing iron oxide compared with a regular UV-only broad-spectrum sunscreen.[9] Patients applied HQ as a depigmenting agent and were assessed by MASI, colorimetry and histologic analysis. The group that used UV-iron oxide sunscreen had greater improvements than the UV-only group. Hence, the depigmenting efficacy of HQ was enhanced with concomitant sunscreen use.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT by Vázquez and Sánchez.,[10] among 53 patients who concomitantly used 3% HQ with sunscreen, nearly 96.2% of patients showed improvement as compared to 80.7% of those using a placebo. Thus, a broad spectrum sunscreen not only prevents relapses of melasma but also enhances the efficacy of other topical therapies.

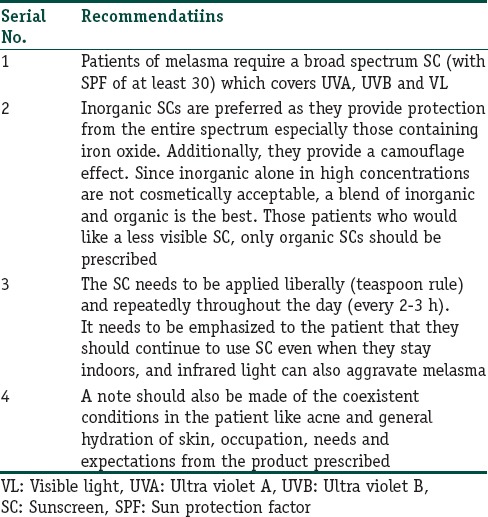

Based on the available literature, the following recommendations can be made for the use of sunscreens [Table 1]. The authors strongly believe that sunscreens should be prescribed to all patients of melasma, as it has been shown to be effective in reducing pigmentation following sun exposure.

Table 1.

Recommendations for use of sunscreens

Role of camouflage

It can take a long time for the patient to see results with the treatment prescribed, during which the option of cosmetic camouflage should be offered. There are several options available in various shades to suit the skin tone. It is important to choose easy-to-blend formulas that are nonirritating and provide smooth coverage.

Topical treatment

Phenolic compounds

Hydroquinone

HQ is the prototype depigmenting agent used in melasma that exerts its effect by inhibiting tyrosinase, the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin synthesis. HQ also affects the membranous structures of melanocytes and causes their apoptosis.

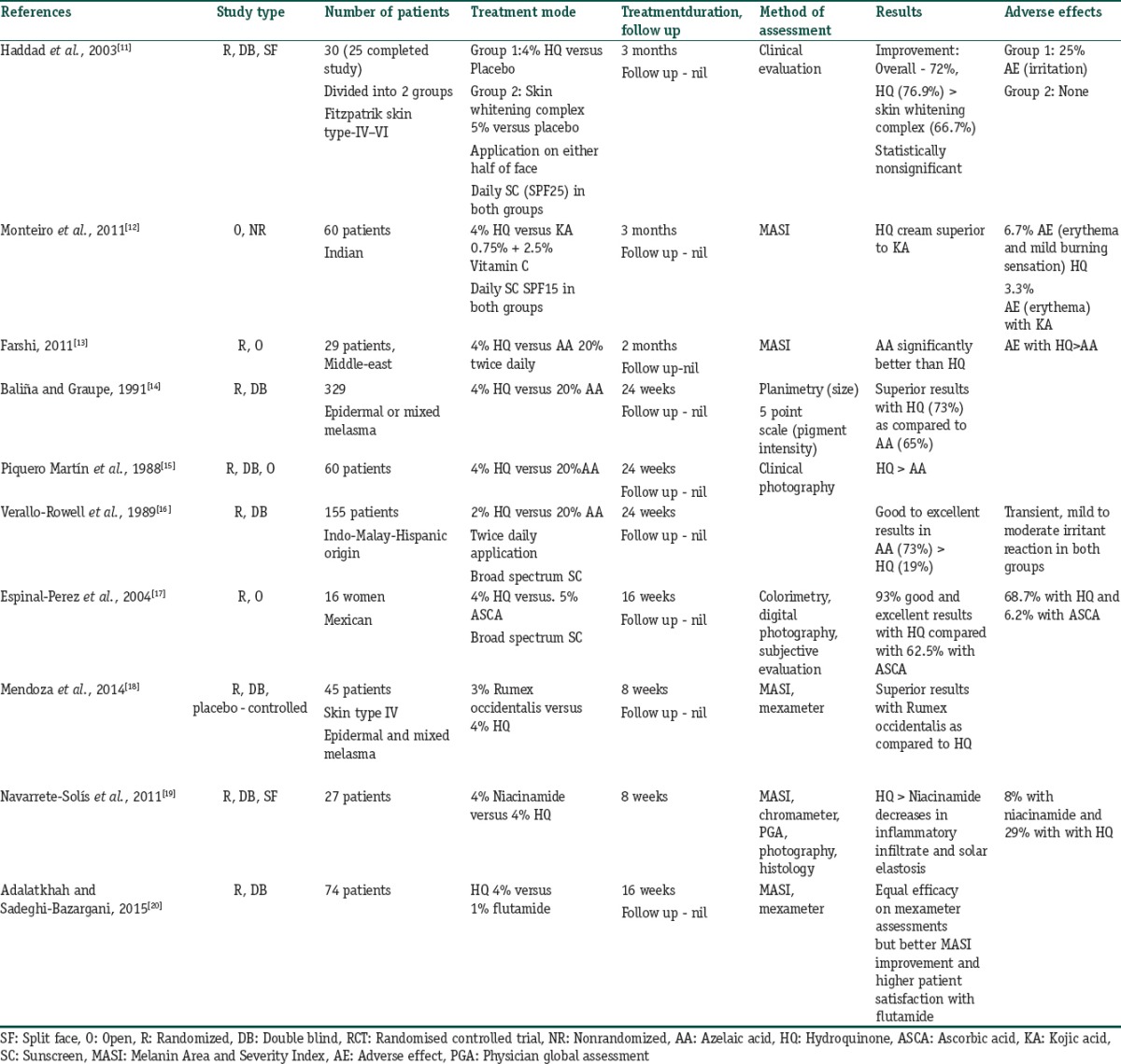

HQ 2%–4% is prominently used as mono-therapy and is summarized in Table 2.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

Table 2.

Summary of studies evaluating the role of hydroquinone mono therapy in melasma

In a controlled study (n = 56), both 2% and 5% HQ creams were found to be equally effective, and marked improvement was recorded in 80% of the patients.[21] However, few inflammatory reactions occurred with the former. Concentration more than 5% may cause more irritation and worsening of hyperpigmentation in the form of exogenous ochronosis on prolonged use.

Pigment lightening by HQ becomes evident after 5–7 weeks of the treatment and is recommended to be continued for at least 3 months and up to 1 year.[22]

Hydroquinone in dual combination

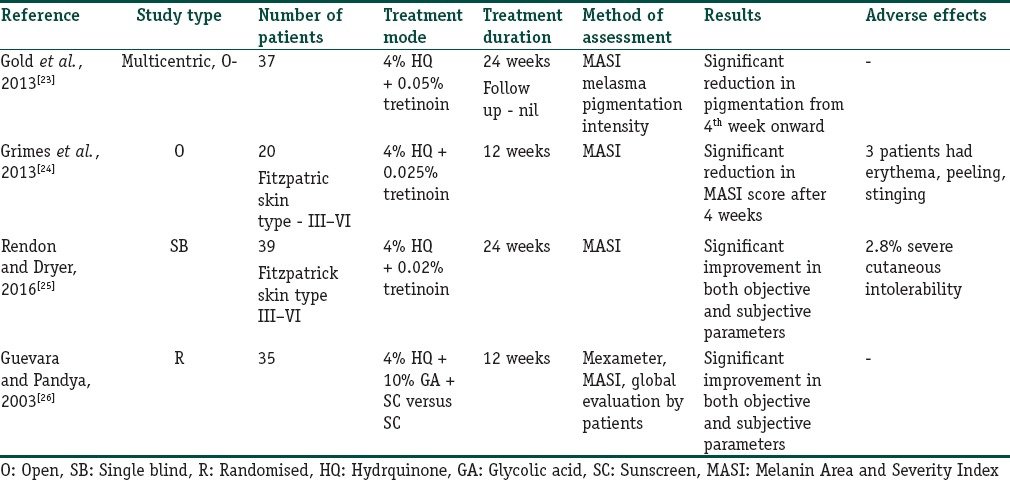

HQ has been used in combination with other topical agents such as tretinoin and glycolic acid. Retinoids inhibit the transcription of tyrosinase thereby inhibiting melanogenesis. The studies summarising the use of HQ in dual combination have been listed in Table 3.[23,24,25,26]

Table 3.

Summary of the studies where hydroquinone has been used in dual combination

Triple combination

One of the first combination topical therapies developed for the treatment of hyperpigmentation was the Kligman–Willis formula, consisting of 5% HQ, 0.1% tretinoin, and 0.1% dexamethasone.

The theory behind the effectiveness of this combination of agents is that tretinoin prevents the oxidation of HQ and improves epidermal penetration while the topical corticosteroid (TCS) reduces irritation due to the other two ingredients and decreases cellular metabolism, further inhibiting melanin synthesis.

To suit different skin types, the original Kligman's formula has been modified in many ways through addition/alteration of one or more of its components. Maximum experimentation has been done with the TCS component, namely, the addition of mid to high potent, fluorinated/non fluorinated agents and their concentration. Furthermore, the concentration of tretinoin and HQ has been kept low in most formulations. Combination regimes are found to be more efficacious and faster acting than monotherapies, thereby shortening the treatment duration and reducing the AE due to an individual drug.

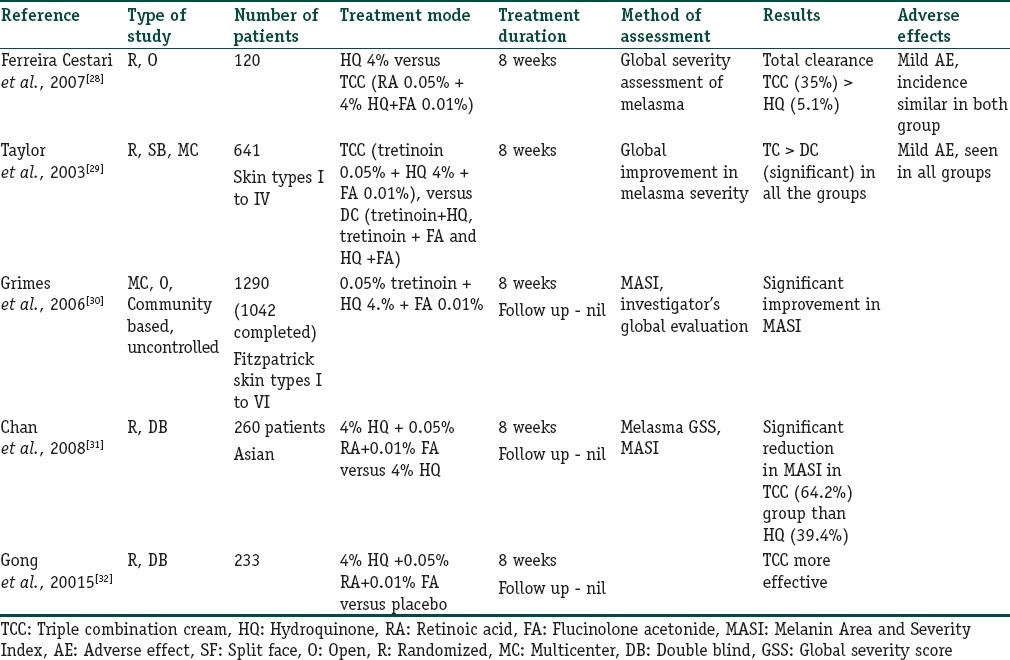

The synergistic action of the three topical agents achieves significantly higher depigmentation than either agent alone. According to a Cochrane Collaboration Review (2010), the triple-combination cream (TCC) having 4% HQ, 0.05% tretinoin, and 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide was significantly more effective in lightening melasma than HQ alone (relative risk [RR] 1.58, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.26–1.97) or when compared to the dual combinations of tretinoin and HQ (RR = 2.75, 95% CI 1.59–4.74), tretinoin, and fluocinolone acetonide (RR = 14.00, 95% CI 4.43–44.25), or HQ and fluocinolone acetonide (RR = 10.50, 95% CI 3.85–28.60). Table 4 summarises the studies which have evaluated the role of triple combination cream in melasma.[27,28,29,30,31,32]

Table 4.

Summary of the studies where role of triple-combination cream has been evaluated in melasma

Triple combination cream in long-term and maintenance treatment of melasma

Melasma is a persistent disorder of pigmentation and relapse after initial improvement is common. Development of a maintenance regimen after initial improvement would help in the management.

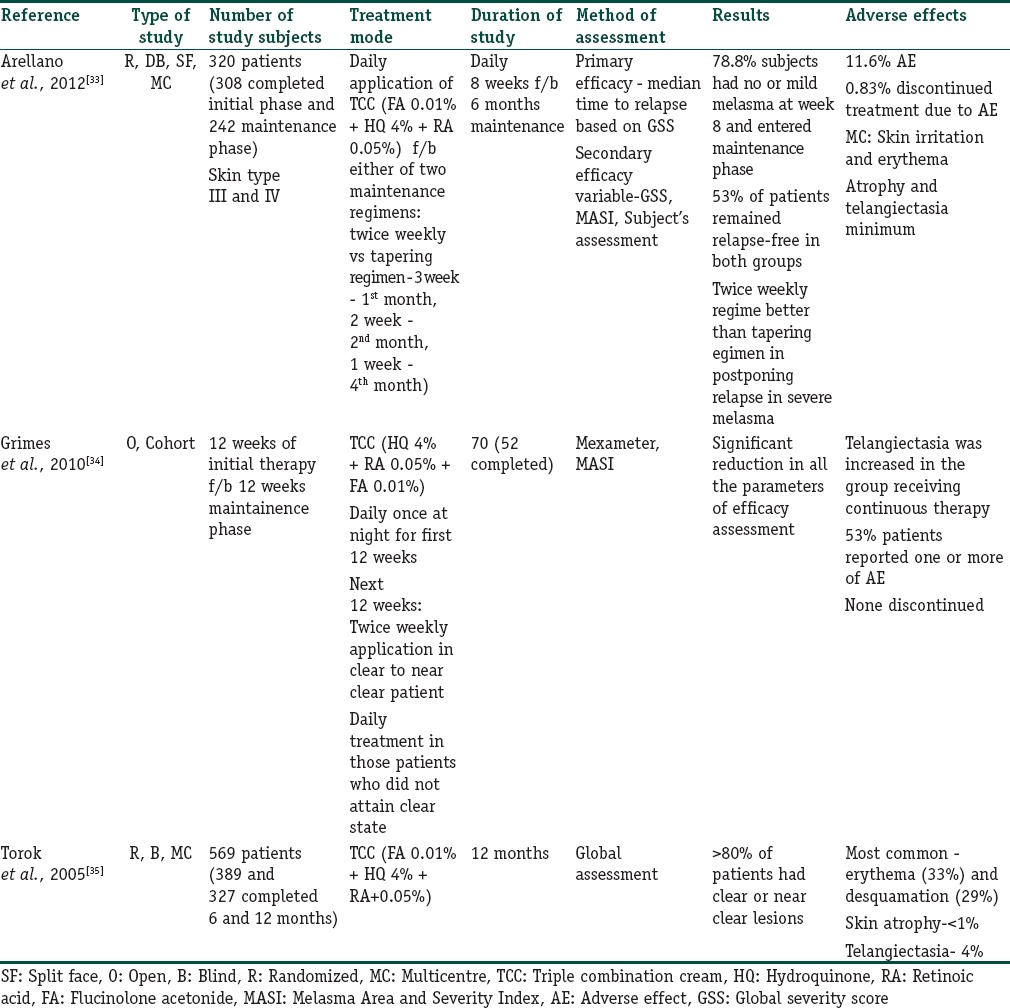

There are controversies regarding the safety of use of TCS based TCC in long-term treatment of melasma. Apart from a few studies on fluocinolone based TCC, there is a dearth of studies evaluating the safety of TCC for long-term use. There are three studies where TCC has been used as a maintenance treatment for melasma Table 5.[33,34,35]

Table 5.

Summary of studies evaluating the long term safety of triple-combination cream in melasma

The studies in Table 5 show that fluocinolone based TCCs can be used as maintenance regimen for more than 8 weeks up to a maximum period of 1 year in either daily/intermittent/tapering dose regimen. Adverse effects such as skin atrophy and telangiectasia were found to be quite low even on continuing this regimen for more than 6 months. However, daily treatment in the long term is associated with more AE while intermittent therapy was associated with higher relapse of melasma in one study.[35]

In one RCT, objective reduction of melanin and presence of erythema was assessed in patients receiving maintenance therapy following initial 8 weeks of the treatment regimen. Using narrowband reflectance spectrophotometer, it was shown that there was no difference between melanin levels in the melasma lesions in patients following either twice weekly or tapering regimen.[36] Adverse effects were rare in both phases of the study. There was borderline reduction in erythema with the tapering regimen.

Triple combinations using mid–potent corticosteroid

Triple combination using mometasone furoate as the steroidal component was quite popular in our country until recently. Despite the paucity of supporting evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of the combination, it has been used rampantly in the last decade, both as physician's prescription and over-the-counter drug. This indiscreet usage has resulted in a number of AE in many patients.

In a retrospective study performed on 60 Indian patients of melasma who had used a mometasone-based TCC for at least 3 weeks over the past 1 year, it was found that majority (51.7%) of the patients had used it well beyond the recommended period.[37] More than half of the patients showed steroid-related AE such as atrophy (19/60), telangiectasia (26/60), hypertrichosis (17/60), and acneiform eruption (11/60) while using this treatment for more than 2 months and almost all the patients were affected when they used it beyond 6 months. In addition, one-third of the patients complained of worsening of pigmentation and the rest claimed that their disease was the same as before and no patient rated his/her disease as better than what he/she had before the initiation of treatment. Furthermore, there were complaints of an increase in the area of skin involvement that had occurred after stoppage of the TCC. Thus, triple combination topical therapy using low potent TCSs should be used. If properly supervised, this can be an effective drug in keeping the pigmentation under control.

Important points

HQ alone in a concentration of 2% to 5% can be used as an effective monotherapy. It is found to be more efficacious than KA and AA. 4% HQ has been found to be more efficacious than 2% HQ as compared to 20% AA in most of the studies. Pigment lightening is observed in 3–6 months time. Higher of HQ is associated with increased risk of inflammatory response and long-term use may give rise to AEs like exogenous ochronosis

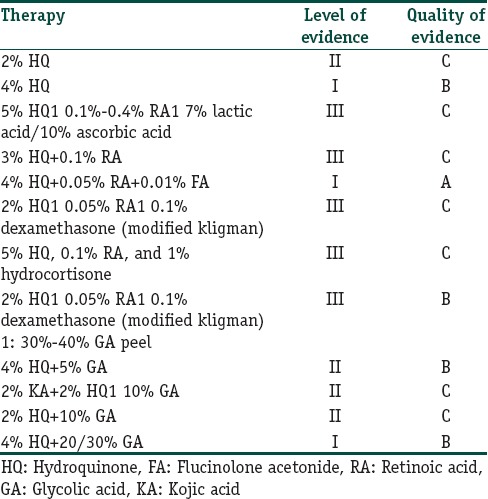

Table 6 lists the level and quality of evidence of use of HQ as monotherapy and in combination with other agents

While there has been a shift from the original Kligman's regimen, the most well-studied formulation is that of 4% HQ, 0.05% tretinoin, and 0.01% FA. It has level A quality of evidence in treating melasma and is approved by the US FDA

When used daily for about 2 months, it results in clearing or near clearing of lesions in several well-designed RCTs

Long-term therapy with TCC for more than 6 months, when used daily is invariably associated with AEs such as atrophy and telangiectasia. Although, the incidence was found to be low in the mentioned studies

It can be used as maintenance regimen for long-term response and is useful in preventing relapse. However, the frequency of application (daily/intermittent/tapering) determines the safety profile

There is a paucity of well-designed RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy of this regimen as maintenance therapy and duration of treatment in Indian population

Mometasone based TCC leads to the rapid lightening of pigmentation (within 3 weeks), but the relapse is also very fast. Further worsening of pigmentation and increase in the area of the original lesion has also been experienced by both the patients and physicians. Long-term use is invariably associated with topical steroid associated AEs such as atrophy, telangiectasia, hirsutism, and acneiform eruption.

Table 6.

Level and quality of evidence for melasma therapies using hydroquinone alone and in various combinations

Mequinol

Mequinol, 4-hydroxyanisole, is a phenolic compound that acts as a competitive inhibitor of tyrosinase. It has been used in combination with tretinoin in the treatment of solar lentigines.[38] However, there is only one case series that has assessed its role in melasma.,[39] in which 5 male patients with melasma were treated with mequinol 2% tretinoin 0.01% topical solution for 16 weeks. Four of 5 patients achieved complete clearance of melasma at 12 weeks with minimal AE.

Due to the paucity of literature, we cannot make a recommendation for mequinol in melasma.

Nonphenolic compounds

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids reduce pigmentation by decreasing the epidermal turnover and its anti-metabolic effect on melanocytes. Both fluorinated and nonfluorinated steroids have been used in the TCC in various formulations. However, their use as monotherapy is not recommended due to the plethora of AE and misuse by the patients.

Azelaic acid

Azelaic acid (AA) is a nonphenolic dicarboxylic acid that acts by competitively inhibiting tyrosinase enzyme. It inhibits DNA synthesis and mitochondrial enzymes causing anti-proliferative and cytotoxic effects on abnormal melanocytes. It has no effect on the normally pigmented skin.

In a prospective, single-blinded, split face comparison study, 40 Indian patients with melasma applied AA cream 20% to one half of the face for 24 weeks and clobetasol 0.05% for eight weeks followed by AzA cream 20% for the next 16 weeks. Sequential therapy was associated with more significant improvement than monotherapy.[40]

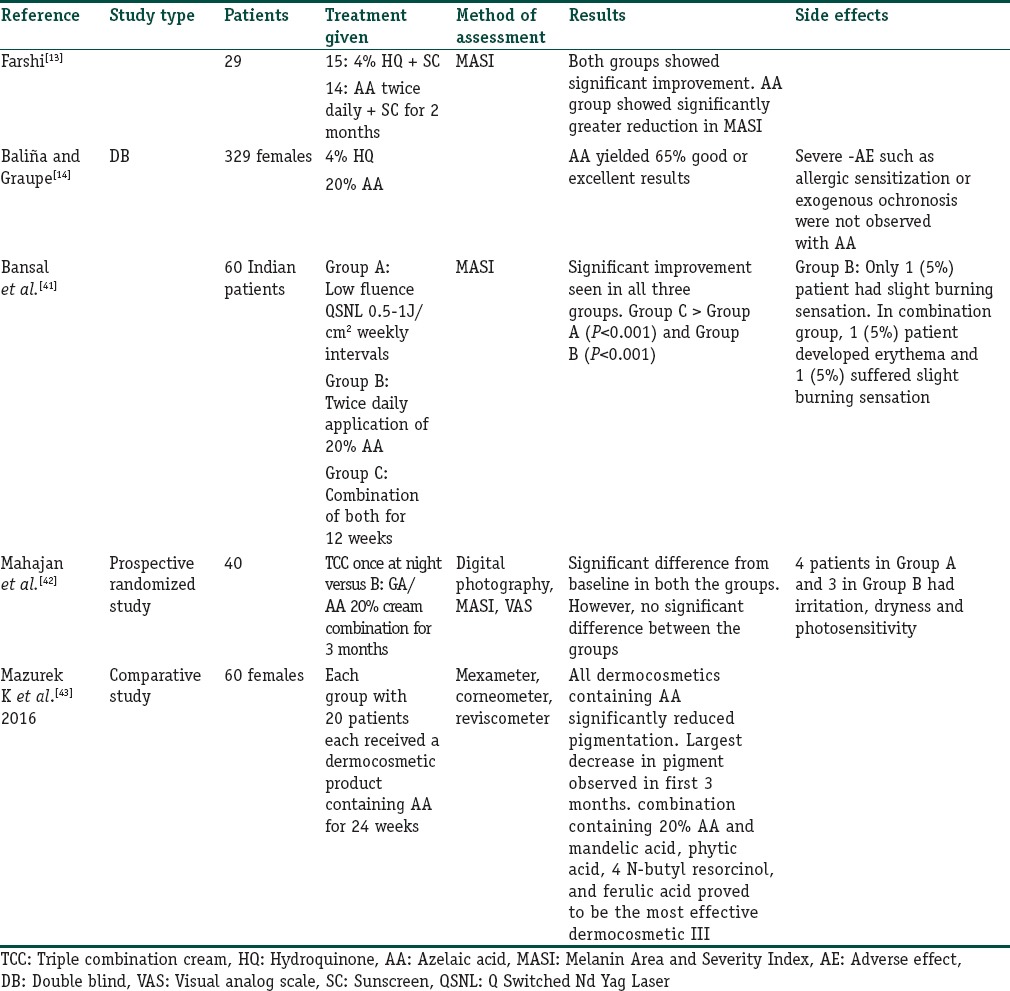

AA has a good safety profile but may rarely cause erythema and stinging. By its efficacy and good safety profile, it is a good option for patients who cannot tolerate TCC. Table 7 summarizes the clinical trials with AA.[13,14,41,42,43]

Table 7.

Summary of clinical trials with azelaic acid

Level and quality of evidence: IB

Kojic acid

Kojic acid (KA) is hydrophilic fungal derivative that inhibits tyrosinase, by chelating copper at the active site of the enzyme. It is used in a concentration of 1%–4%.

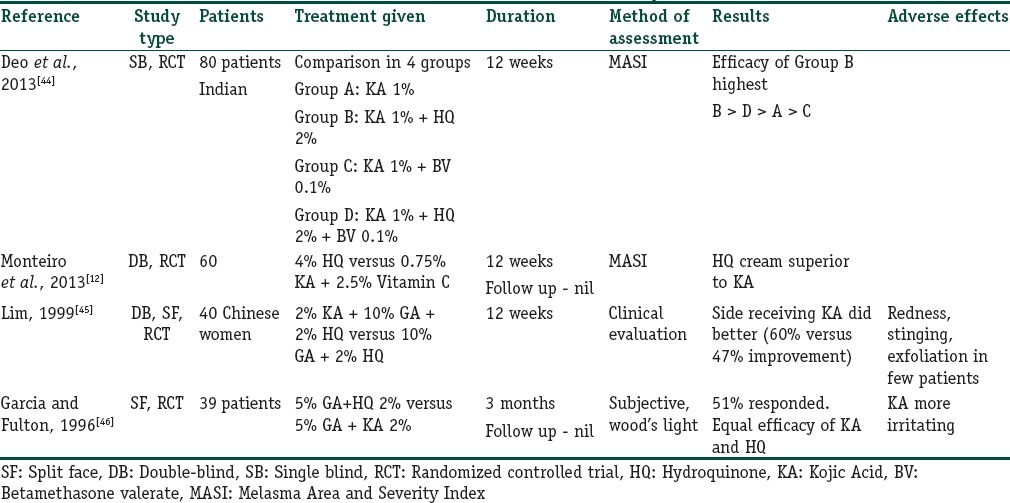

Various studies have been done to evaluate its role in melasma and these have shown mixed results [Table 8].[12,44,45,46] KA is less effective when used as monotherapy but shows good results in combination with HQ and GA.

Table 8.

Summary of studies outlining the role of kojic acid in melasma

Level and quality of evidence: B

Arbutin

It is a derivative of D-glucopyranoside that competitively inhibits tyrosinase and is cytotoxic to melanocytes. Deoxyarbutin is the synthetic derivative of arbutin with higher efficacy and stability. In a prospective, open-label study, a formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% was found to be associated with significant reduction in MASI scores.[47] Arbutin has also been used in combination with NdYAG laser and found to have good results in melasma.[48]

Level and quality of evidence: C

Vitamin C

Vitamin C inhibits melanogenesis by acting as a reducing agent at various oxidative steps in melanin synthesis. However, stability is an issue with the Vitamin C preparations due to rapid oxidation. Magnesium ascorbic phosphate is a stable esterified derivative of Vitamin C.

In a split-face RCT, 16 women with melasma used 5% AA and 4% HQ on either side of the face for 16 weeks.[17] HQ showed significantly better results but more AE (93% vs. 62.5%), as compared to Vitamin C.

Level and quality of evidence IB

Niacinamide

It is the active amide of Vitamin B3 that reduces pigmentation by inhibiting the transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes. In a double-blind RCT, 4% niacinamide cream was compared with 4% HQ in 27 melasma patients. About 44% of patients showed good to excellent improvement with niacinamide compared to 55% with HQ. AE was less with niacinamide and histopathology showed decreased inflammatory infiltrate and solar elastosis in the treated lesions.[19]

Level and quality of evidence: IB

Newer drugs

A number of newer derivatives of the conventional drugs, synthetic compounds and botanicals derived from natural sources are being studied for their potential role in reducing melanogenesis and pigmentation. These compounds have been found to lighten melasma and hyperpigmentation induced by UV exposure. They can prove to be effective in the treatment of melasma, especially as adjuncts to first-line treatments and for maintenance. These agents work through various mechanisms such as inhibition of activity or maturation of tyrosinase enzyme as well as acceleration of its degradation. Other mechanisms include anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, peroxidase inhibition or breaking down melanin, prevention of transfer of melanosomes from melanocytes to the keratinocytes (niacinamide) and stimulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (octadienedioic acid).

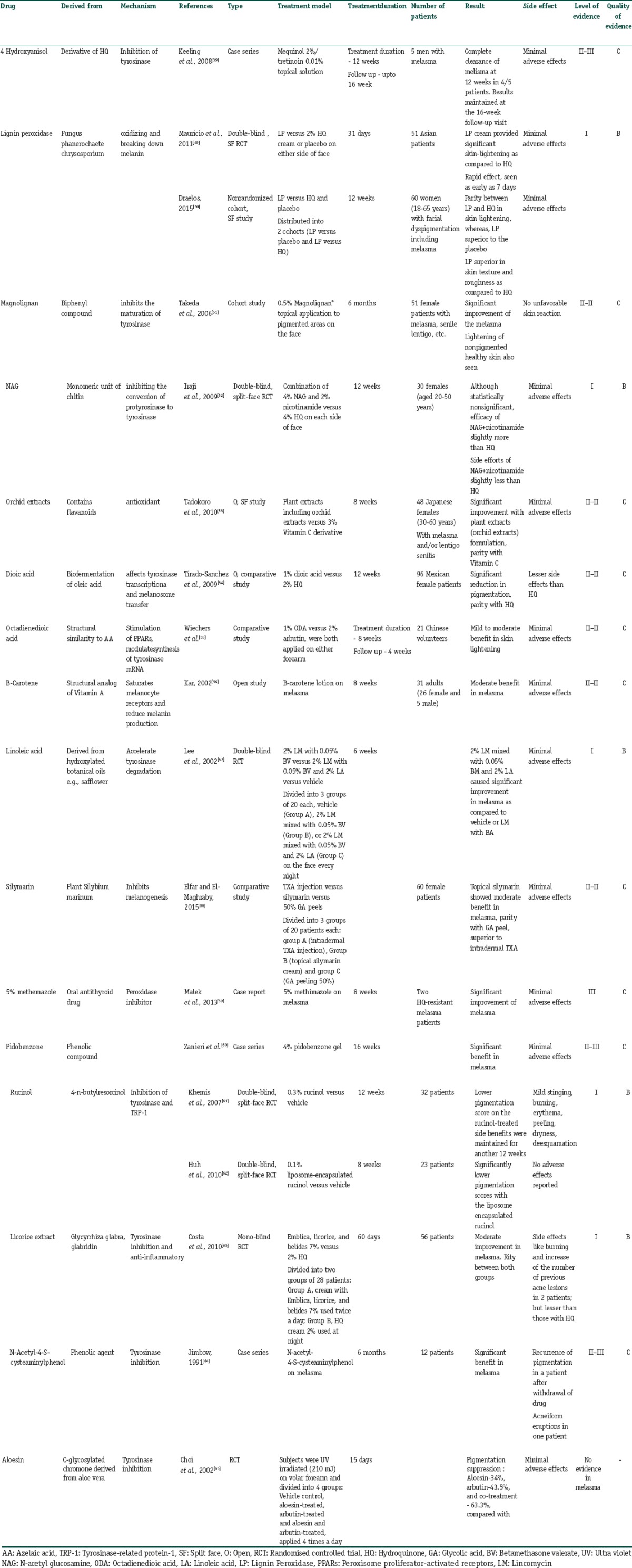

A number of these drugs have been studied in human trials on melasma, solar lentigines or UV induced hyperpigmentation with encouraging results as elucidated in Table 9.[39,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] Others such as cinnamic acid, green tea extracts, flavonoids, gentistic acid, pyronic acrylic acid inhibitors, zinc dihydrolipoylhistidinate and resveratrol are in the process of development and preclinical studies. The knowledge of the properties of these agents enables the dermatologist to choose a product that gives the best benefit to their patients while minimizing the side effects Although experimental evidence suggests their possible benefits, rigorous controlled trials are mostly lacking for these agents. Thus, these cannot be strongly recommended for melasma at present and more studies are required to further elucidate their role.

Table 9.

Summary of the newer drugs for treatment of melasma

Oral drugs for melasma

Tranexamic acid (TXA) (Trans-4-Aminomethylcyclohexane-carboxylic acid) is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine. It binds reversibly to the lysine binding sites on plasminogen molecules and inhibits plasminogen activator (PA) and thus the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin. Plasminogen also exists in the basal epidermal cells and keratinocytes and induction of this keratinocyte-PA system by UV exposure results in melanogenesis through production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. It is through prevention of binding of plasminogen to keratinocyte, TA inhibits UV-induced plasmin activity in keratinocytes, thereby decreasing melanogenesis through reduced production of PGs.

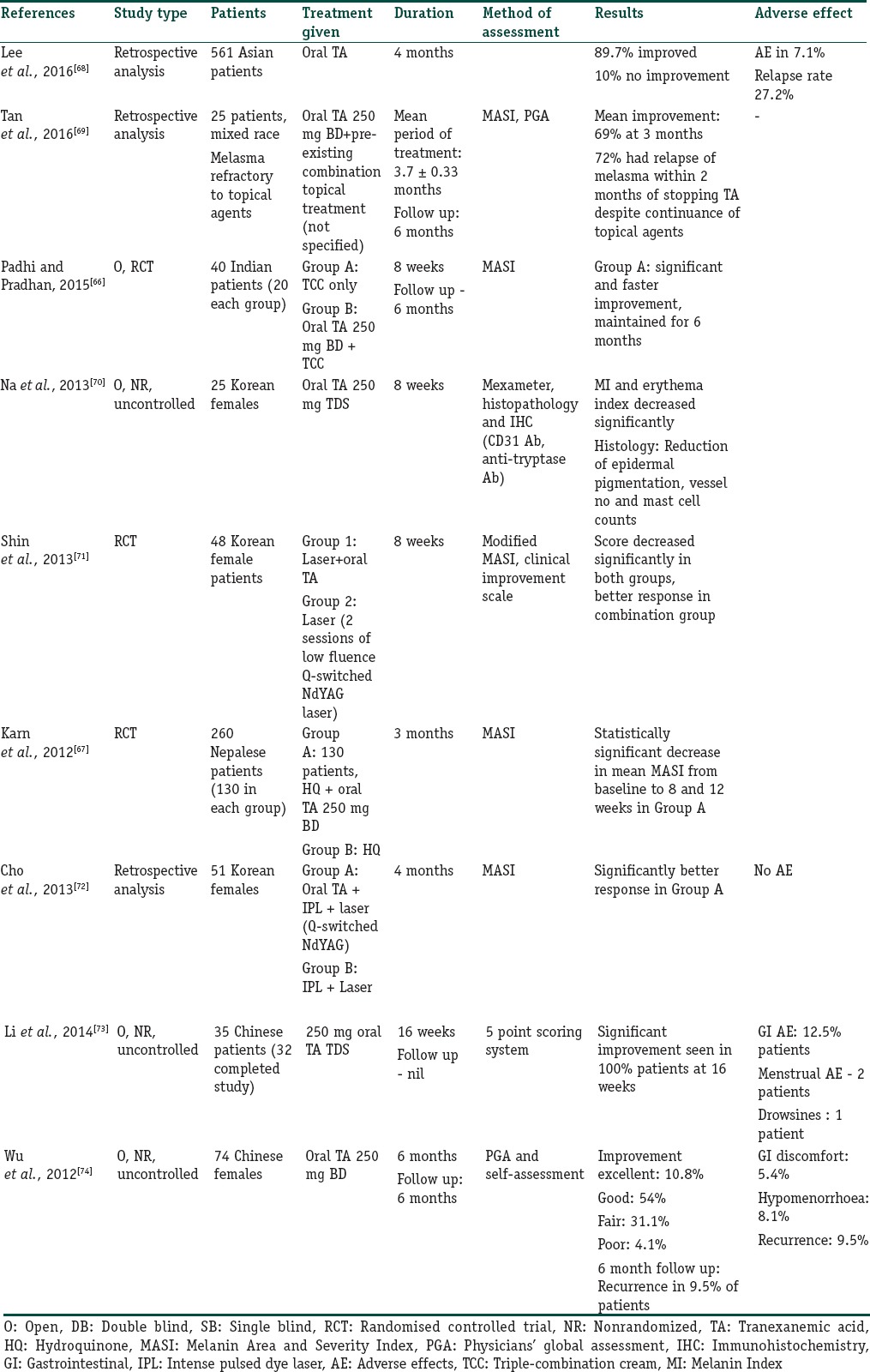

The effect of oral TA in melasma has been studied in multiple trials, as summarized in Table 10.[66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74] However, only two of them are RCTs. Padhi and Pradhan[66] evaluated the efficacy of oral TA in 40 Indian patients who were given oral TXA (250 mg twice a day for 8 weeks) in addition to a TCC, (fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, tretinoin 0.05%, and HQ2%). There was a faster reduction in MASI in the combination group and the efficacy was maintained throughout the 6 months follow-up period.

Table 10.

Summary of clinical trials with tranexemic acid

In another RCT conducted by Karn et al., in 260 patients of melasma, the efficacy of TA was compared to routine topical treatment. One group received oral TA 250 mg twice a day for 3 months along with routine topical measures, whereas the other group received routine topical treatment alone.[67] The combination treatment group showed statistically significant decrease in mean MASI from baseline to 8 and 12 weeks. The authors concluded that oral TA provides rapid and sustained improvement in the treatment of melasma.

Overall recommendation: as per available evidence, oral TA may be used alone or as an adjuvant to conventional topical drugs. It can also be used when other topical treatments fail. However, there are limited studies with small sample size and variable dosage and duration. Larger RCTs are required to evaluate the efficacy and long-term follow-up as well as serious AE.

Other oral drugs

Procyanidin

There is only one RCT that has evaluated the efficacy of oral procyanidin in melasma. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted by Handog EB et al., in 60 Filipino women with epidermal melasma, the safety and efficacy of oral procyanidin plus Vitamin A, C, E were compared with placebo.[75] The patients received either the drug or placebo twice daily with meals for 8 weeks. Results were evaluated using mexameter, MASI and global evaluation by the patient. The procyanidin group showed a significant improvement in pigmentation with minimal AEs.

However, this study had the limitation that procyanidin was not evaluated as monotherapy and thus, the benefit achieved cannot be ascribed to procyanidin alone.

Evidence level-B

Oral polypodium leucotomos extract

One double-blinded RCT was done with oral polypodium leucotomos extract (240-mg thrice a day) for 12 weeks among 40 hispanic patients with moderate to severe melasma.[76] There was an improvement in MASI and melasma-related quality-of-life, but it was not statistically significant.

Evidence level B

Recommendation: there is lack of evidence to recommend this drug in melisma.

Pycnogenol

Pycnogenol is an extract of the bark of Pinus pinaster, a French pine tree. It has antioxidant properties, increases the endogenous antioxidant enzyme system and also protects against UV radiation. Its efficacy in melasma was evaluated in a single clinical trial conducted by Ni et al. in 30 women with melasma who took one tablet of Pycnogenol (25 mg) with meals three times daily for 30 days.[77] MASI and pigmentary intensity index decreased after treatment. Several other symptoms such as fatigue, constipation, pains in the body, and anxiety were also improved, and no AE was seen.

It cannot be recommended in melasma until further studies are available.

Glutathione

No available study in melasma

Conclusions

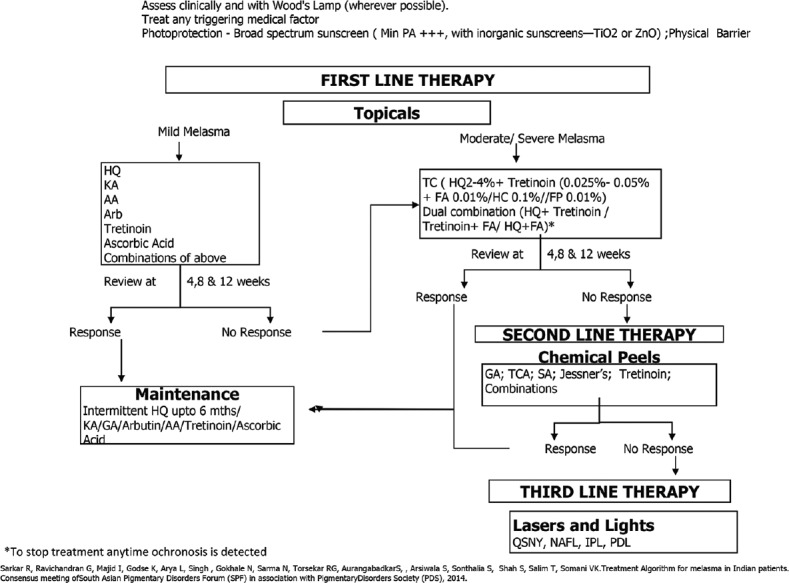

Medical management of melasma with topical skin lightening therapy still remains the mainstay of therapy and should always be used as first-line agents. HQ, triple combination therapy, other agents and upcoming oral therapies will be used in combination in the future. The SPF with the Pigmentary Disorders Society suggests an easy to follow an algorithm, Figure 1, where peels and lasers form second- and third-line therapies respectively.

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for melasma in India, by a Consensus meeting of SPF(South Asian Pigmentary Disorders forum) with Pigmentary Disorders Society(PDS)

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Although topical therapy with hydroquinone and triple combination therapy leads the list in treatment of melasma, a careful watch for side effects of topical corticosteroids must be done. Mometasone or fluticasone containing creams should be totally discouraged.

A large number of newer botanical agents offer a suitable alternative and should be used for maintaining lightening of melasma.

Sunscreens containing more of inorganic sunscreens especially iron oxide appear more promising.

Oral agents, especially tranexamic acid has been well studied and used but does need more follow up for side effects.

Treatment of medical conditions concomitantly is important.

Acknowlegment

The Consensus Meeting of a group South Asian Pigmentary Disorders Forum with Pigmentary Disorders Society was made possible by an educational grant by Galderma, India.

References

- 1.Sivayathorn A. Melasma in orientals. Clin Drug Invest. 1995;10:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarkar R, Puri P, Jain RK, Singh A, Desai A. Melasma in men: A clinical, aetiological and histological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:768–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ortonne JP, Arellano I, Berneburg M, Cestari T, Chan H, Grimes P, et al. A global survey of the role of ultraviolet radiation and hormonal influences in the development of melasma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1254–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamega Ade A, Miot LD, Bonfietti C, Gige TC, Marques ME, Miot HA, et al. Clinical patterns and epidemiological characteristics of facial melasma in Brazilian women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:151–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutfi RJ, Fridmanis M, Misiunas AL, Pafume O, Gonzalez EA, Villemur JA, et al. Association of melasma with thyroid autoimmunity and other thyroidal abnormalities and their relationship to the origin of the melasma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:28–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopichandani K, Arora P, Garga U, Bhardwaj M, Sharma N, Gautam RK. Hormone profile of melasma in Indian females. Pigment Int. 2015;2:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakhdar H, Zouhair K, Khadir K, Essari A, Richard A, Seité S, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a broad-spectrum sunscreen in the prevention of chloasma in pregnant women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:738–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boukari F, Jourdan E, Fontas E, Montaudié H, Castela E, Lacour JP, et al. Prevention of melasma relapses with sunscreen combining protection against UV and short wavelengths of visible light: A prospective randomized comparative trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:189–900. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castanedo-Cazares JP, Hernandez-Blanco D, Carlos-Ortega B, Fuentes-Ahumada C, Torres-Álvarez B. Near-visible light and UV photoprotection in the treatment of melasma: A double-blind randomized trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2014;30:35–42. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vázquez M, Sánchez JL. The effcacy of a broad-spectrum sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. A randomized double blinded controlled trial. Cutis. 1983;32:95–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad AL, Matos LF, Brunstein F, Ferreira LM, Silva A, Costa D, Jr, et al. A clinical, prospective, randomized, double-blind trial comparing skin whitening complex with hydroquinone vs. Placebo in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:153–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monteiro RC, Kishore BN, Bhat RM, Sukumar D, Martis J, Ganesh HK, et al. A comparative study of the efficacy of 4% hydroquinone vs.0.75% kojic acid cream in the treatment of facial melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:157. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.108070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farshi S. Comparative study of therapeutic effects of 20% azelaic acid and hydroquinone 4% cream in the treatment of melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:282–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baliña LM, Graupe K. The treatment of melasma 20% azelaic acid versus 4% hydroquinone cream. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:893–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piquero Martín J, Rothe de Arocha J, Beniamini Loker D. Double-blind clinical study of the treatment of melasma with azelaic acid versus hydroquinone. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1988;16:511–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verallo-Rowell VM, Verallo V, Graupe K, Lopez-Villafuerte L, Garcia-Lopez M. Double-blind comparison of azelaic acid and hydroquinone in the treatment of melasma. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1989;143:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinal-Perez LE, Moncada B, Castanedo-Cazares JP. A double-blind randomized trial of 5% ascorbic acid vs.4% hydroquinone in melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:604–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendoza CG, Singzon IA, Handog EB. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial on the efficacy and safety of 3% Rumex occidentalis cream versus 4% hydroquinone cream in the treatment of melasma among Filipinos. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1412–6. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarrete-Solís J, Castanedo-Cázares JP, Torres-Álvarez B, Oros-Ovalle C, Fuentes-Ahumada C, González FJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized clinical trial of niacinamide 4% versus hydroquinone 4% in the treatment of melasma. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:379173. doi: 10.1155/2011/379173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adalatkhah H, Sadeghi-Bazargani H. The first clinical experience on efficacy of topical flutamide on melasma compared with topical hydroquinone: A randomized clinical trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:4219–25. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S80713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arndt KA, Fitzpatrick TB. Topical use of hydroquinone as a depigmenting agent. J Am Med Assoc. 1965;194:965–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prignano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, Lotti T. Therapeutical approaches in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:337–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.006. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold M, Rendon M, Dibernardo B, Bruce S, Lucas-Anthony C, Watson J, et al. Open-label treatment of moderate or marked melasma with a 4% hydroquinone skin care system plus 0.05% tretinoin cream. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:32–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimes P, Watson J. Treating epidermal melasma with a 4% hydroquinone skin care system plus tretinoin cream 0.025% Cutis. 2013;91:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rendon M, Dryer L. Investigator-blinded, single-center study to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of a 4% hydroquinone skin care system plus 0.02% tretinoin cream in mild-to-moderate melasma and photodamage. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:466–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guevara IL, Pandya AG. Safety and efficacy of 4% hydroquinone combined with 10% glycolic acid, antioxidants, and sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:966–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2003.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajaratnam R, Halpern J, Salim A, Emmett C. Interventions for melasma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD003583. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003583.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira Cestari T, Hassun K, Sittart A, de Lourdes Viegas M. A comparison of triple combination cream and hydroquinone 4% cream for the treatment of moderate to severe facial melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2007;6:36–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2007.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor SC, Torok H, Jones T, Lowe N, Rich P, Tschen E, et al. Efficacy and safety of a new triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2003;72:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimes P, Kelly AP, Torok H, Willis I. Community-based trial of a triple-combination agent for the treatment of facial melasma. Cutis. 2006;77:177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan R, Park KC, Lee MH, Lee ES, Chang SE, Leow YH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of a fixed triple combination (fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%, hydroquinone 4%, tretinoin 0.05%) compared with hydroquinone 4% cream in Asian patients with moderate to severe melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong Z, Lai W, Zhao G, Wang X, Zheng M, Li L, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluocinolone acetonide, hydroquinone, and tretinoin cream in Chinese patients with melasma: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, parallel-group study. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35:385–95. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arellano I, Cestari T, Ocampo-Candiani J, Azulay-Abulafia L, Bezerra Trindade Neto P, Hexsel D, et al. Preventing melasma recurrence: Prescribing a maintenance regimen with an effective triple combination cream based on long-standing clinical severity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:611–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimes PE, Bhawan J, Guevara IL, Colón LE, Johnson LA, Gottschalk RW, et al. Continuous therapy followed by a maintenance therapy regimen with a triple combination cream for melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:962–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torok H, Taylor S, Baumann L, Jones T, Wieder J, Lowe N, et al. A large 12-month extension study of an 8-week trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of triple combination (TC) cream in melasma patients previously treated with TC cream or one of its dyads. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:592–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hexsel D, Soirefmann M, Fernandes JD, Siega C. Objective assessment of erythema and pigmentation of melasma lesions and surrounding areas in long-term management regimens with triple combination. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:444–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majid I. Mometasone-based triple combination therapy in melasma: Is it really safe? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:359–62. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.74545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarratt M. Mequinol 2%/tretinoin 0.01% solution: An effective and safe alternative to hydroquinone 3% in the treatment of solar lentigines. Cutis. 2004;74:319–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keeling J, Cardona L, Benitez A, Epstein R, Rendon M. Mequinol 2%/tretinoin 0.01% topical solution for the treatment of melasma in men: A case series and review of the literature. Cutis. 2008;81:179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkar R, Bhalla M, Kanwar AJ. A comparative study of 20% azelaic acid cream monotherapy versus a sequential therapy in the treatment of melasma in dark-skinned patients. Dermatology. 2002;205:249–54. doi: 10.1159/000065851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bansal C, Naik H, Kar HK, Chauhan A. A comparison of low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with topical 20% azelaic acid cream and their combination in melasma in Indian patients. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5:266–72. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.104915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan R, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D, Kumaran MS, Sharma R. Glycolic acid peels/azelaic acid 20% cream combination and low potency triple combination lead to similar reduction in melasma severity in ethnic skin: Results of a randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:147–52. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mazurek K, Pierzchała E. Comparison of efficacy of products containing azelaic acid in melasma treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:269–82. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deo KS, Dash KN, Sharma YK, Virmani NC, Oberai C. Kojic acid vis-a-vis its combinations with hydroquinone and betamethasone valerate in melasma: A Randomized, single blind, comparative study of efficacy and safety. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:281–5. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.113940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim JT. Treatment of melasma using kojic acid in a gel containing hydroquinone and glycolic acid. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:282–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia A, Fulton JE., Jr The combination of glycolic acid and hydroquinone or kojic acid for the treatment of melasma and related conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:443–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crocco EI, Veasey JV, Boin MF, Lellis RF, Alves RO. A novel cream formulation containing nicotinamide 4%, arbutin 3%, bisabolol 1%, and retinaldehyde 0.05% for treatment of epidermal melasma. Cutis. 2015;96:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polnikorn N. Treatment of refractory melasma with the medLite C6 Q-switched Nd:YAG laser and alpha arbutin: A prospective study. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:126–31. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.487910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mauricio T, Karmon Y, Khaiat A. A randomized and placebo-controlled study to compare the skin-lightening efficacy and safety of lignin peroxidase cream vs.2% hydroquinone cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Draelos ZD. A split-face evaluation of a novel pigment-lightening agent compared with no treatment and hydroquinone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:105–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda K, Arase S, Sagawa Y, Shikata Y, Okada H, Watanabe S, et al. Clinical evaluation of the topical application of Magnolignan ® (5,5’-dipropyl-biphenyl-2,2’-diol) for hyperpigmentation on the face. Nishinihon J Dermatol. 2006;68:293–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iraji F, Mehrpour K, Asilian A, Siadat AH, Mohaghegh F. A comparative study to evaluate the efficacy of “4% nacetyl glucosamine+2% nicotinamide” cream versus 4% hydroquinone cream in the treatment of facial melasma: A randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical trial. J Cell Tissue Res. 2009;9:1767–72. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tadokoro T, Bonté F, Archambault JC, Cauchard JH, Neveu M, Ozawa K, et al. Whitening efficacy of plant extracts including orchid extracts on Japanese female skin with melasma and lentigo senilis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:522–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tirado-Sanchez A, Santamaria Roman A, Ponce Olivera RM. Efficacy of dioic acid compared with hydroquinone in treatment of melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:893–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiechers JW, Groenhof FJ, Wortel VA, Miller RM, Hindle NA, Drewitt Barlow A, et al. Octadecenedioic Acid for a More Even Skin Tone. Cosmetics & Toiletries. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com .

- 56.Kar HK. Efficacy of beta-carotene topical application in melasma: An open clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2002;68:320–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee MH, Kim HJ, Ha DJ, Paik JH, Kim HY. Therapeutic effect of topical application of linoleic acid and lincomycin in combination with betamethasone valerate in melasma patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:518–23. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elfar NN, El-Maghraby GM. Efficacy of intradermal injection of tranexamic acid, topical silymarin and glycolic acid peeling in treatment of melasma: A comparative study. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2015;6:280. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malek J, Chedraoui A, Nikolic D, Barouti N, Ghosn S, Abbas O, et al. Successful treatment of hydroquinone-resistant melasma using topical methimazole. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2012.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zanieri F, Assad GB, Campolini P, Lotti T. Melasma: Successful treatment with 4% pidobenzone. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:18–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khemis A, Kaiafa A, Queille-Roussel C, Duteil L, Ortonne JP. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of rucinol serum in patients with melasma: A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huh SY, Shin JW, Na JI, Huh CH, Youn SW, Park KC, et al. Efficacy and safety of liposome-encapsulated 4-n-butylresorcinol 0.1% cream for the treatment of melasma: A randomized controlled split-face trial. J Dermatol. 2010;37:311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costa A, Moisés TA, Cordero T, Alves CR, Marmirori J. Association of emblica, licorice and belides as an alternative to hydroquinone in the clinical treatment of melasma. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:613–20. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jimbow K. N-acetyl-4-S-cysteaminylphenol as a new type of depigmenting agent for the melanoderma of patients with melasma. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1528–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi S, Lee SK, Kim JE, Chung MH, Park YI. Aloesin inhibits hyperpigmentation induced by UV radiation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:513–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Padhi T, Pradhan S. Oral tranexamic acid with fluocinolone-based triple combination cream versus fluocinolone-based triple combination cream alone in melasma: An open labeled randomized comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.164416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karn D, Kc S, Amatya A, Razouria EA, Timalsina M. Oral tranexamic acid for the treatment of melasma. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2012;10:40–3. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v10i4.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee HC, Thng TG, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: A retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:385–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan AW, Sen P, Chua SH, Goh BK. Oral tranexamic acid lightens refractory melasma. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e105–8. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Na JI, Choi SY, Yang SH, Choi HR, Kang HY, Park KC, et al. Effect of tranexamic acid on melasma: A clinical trial with histological evaluation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1035–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shin JU, Park J, Oh SH, Lee JH. Oral tranexamic acid enhances the efficacy of low-fluence 1064-nm quality-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser treatment for melasma in Koreans: A randomized, prospective trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:435–42. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cho HH, Choi M, Cho S, Lee JH. Role of oral tranexamic acid in melasma patients treated with IPL and low fluence QS Nd:YAG laser. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24:292–6. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2011.643220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Y, Sun Q, He Z, Fu L, He C, Yan Y, et al. Treatment of melasma with oral administration of compound tranexamic acid: A preliminary clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:393–4. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu S, Shi H, Wu H, Yan S, Guo J, Sun Y, et al. Treatment of melasma with oral administration of tranexamic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36:964–70. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-9899-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Handog EB, Galang DA, de Leon-Godinez MA, Chan GP. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral procyanidin with Vitamins A, C, E for melasma among Filipino women. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:896–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ahmed AM, Lopez I, Perese F, Vasquez R, Hynan LS, Chong B, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of oral polypodium leucotomos extract as an adjunct to sunscreen in the treatment of melasma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:981–3. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ni Z, Mu Y, Gulati O. Treatment of melasma with pycnogenol. Phytother Res. 2002;16:567–71. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]