Abstract

Introduction:

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is a frequently encountered entity. Facial AN (FAN) is a subset of AN which is being increasingly recognized. Recently, reports hypothesizing the association of FAN with features of metabolic syndrome have been published.

Aims and Objectives:

The aim of this study was to study the clinicodemographic profile of patients with FAN, and to assess the correlation of hypertension, increased waist–hip ratio (WHR), increased body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes mellitus, deranged lipid profile, serum insulin, and impaired oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (parameters of metabolic syndrome) in these patients, as well as to determine the most significant predictor (highest relative risk) of development of FAN.

Methods:

A multicentric case–control study was conducted (123 cases in each group) over a period of 2 years. Data were obtained on the basis of history, examination, and relevant laboratory investigations. Statistical analysis was done using Statistica version 6 (StatSoft Inc., 2001, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA), SPSS statistics version 17 (SPSS Inc., 2008, Illinois, Chicago, USA), and GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., 2007, San Diego, California, USA).

Results:

Mean age of the patients with FAN was 38.83 ± 8.62 years. Mean age of onset of the disease was 30.93 ± 8.18 years. The most common site of face involved was the forehead and temporal region. The most common pigmentation was brown-black. Male sex, positive OGTT, increased WHR, and increased BMI were most significantly related to FAN. Smoking was found to have a protective effect against the development of FAN.

Conclusion:

Here, we document a significant association between male patients with positive OGTT, increased WHR, and BMI and FAN. Thus, we propose that FAN could be considered a morphological marker of metabolic syndrome.

Keywords: Case-control study, facial acanthosis nigricans, metabolic syndrome

What was known?

Acanthosis nigricans is a common dermatosis, with patients frequently found to seek consultations regarding the cosmetic disfigurement. Facial acanthosis nigricans (FAN) is a relatively new entity, the prevalence of which, is increasing in recent times. There have been multiple reports of FAN and a possible association with metabolic syndrome. However, this is the first ever case-control study in an attempt to find out the correlation between this intriguing clinical feature and parameters of metabolic syndrome.

Introduction

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is clinically manifested as dark, velvety, and thickened skin, symmetrically distributed over the neck, axillae, and other flexural regions of the body. In rare circumstances, it is found over the face.[1] Veysey and Ratnavel reported a case of facial AN (FAN), which was associated with obesity and hyperinsulinemia.[2] Verma et al.[3] documented an increased prevalence of obesity and insulin resistance in patients presenting with FAN.[3] However, studies correlating the presence of FAN with features of metabolic syndrome are lacking. With this background, we attempted to determine the systemic predictors of FAN. We present a case–control study of patients with FAN to assess the clinico-epidemiological parameters of patients, and to estimate the correlation of hypertension, increased waist–hip ratio (WHR), increased body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes mellitus, deranged lipid profile, serum insulin, and impaired oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in FAN patients. Further, we have also attempted to determine the most significant predictor of FAN.

Aims and objectives

The aims of this study were to investigate the clinicodemographic profile of patients with FAN; assess the correlation of hypertension, increased WHR, increased BMI, type 2 diabetes mellitus, deranged lipid profile, serum insulin, and impaired OGTT (parameters of metabolic syndrome) in FAN patients; and determine the most significant predictor (highest relative risk) of development of FAN.

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive and consenting patients presenting to the outpatient department of dermatology with clinical features of FAN (brown-to-black pigmentation with ill-defined margins and velvety surface on the face with or without the presence of similar features on neck, axilla, groin, and other flexural regions) were included in this study. An age- and sex-matched control group was included consisting of all the patients presenting to the outpatient department of dermatology without a clinical diagnosis of FAN or having lesions of AN in any other part of the body. To minimize selection bias, recruitment of control group was done by an independent investigator who was not involved in the study in any other role.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with non-FAN causes of facial melanosis were excluded from the study (melasma, lichen planus pigmentosus, pigmented contact dermatitis, Riehl's melanosis, etc.). While selecting the control population, persons with AN (facial or nonfacial) were excluded from the study for obvious reasons.

Study design

This was a multicentric case–control study conducted in the outpatient departments of dermatology of multiple institutes. Ethics Committee clearance was taken from all the participating institutes. The study was conducted over a period of 2 years (February 2015 to January 2017). All the authors contributed equally to the recruitment of cases and generation of data. One hundred and thirty-nine patients with a clinical diagnosis of FAN were found, of which 16 did not give consent for participation. Hence, a total of 123 cases were included in the study. The study recently conducted by Verma et al.[3] recruited 102 cases. The participants were subjected to thorough history taking and clinical examination. Age, sex, occupation, age of onset of FAN, presence of other skin diseases, family history of AN including FAN, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, history of smoking, alcohol intake, history of drug intake, duration of disease, blood pressure, WHR, and BMI were recorded. Menstrual and reproductive history was noted in females.

Cutaneous examination was done, and the lesions of FAN were described in terms of color, texture, and part of face involved. In addition, the presence of AN on other parts of the body was also documented. Other features such as acne, androgenetic alopecia, and acrochordons were also noted. Skin biopsy for histopathological examination was done among consenting patients. Each patient was subjected to fasting blood sugar, fasting serum insulin, OGTT, and lipid profile.

Blood pressure was measured, and 130/85 was considered as the normal level. If any of these levels were higher, the patient was labeled as hypertensive.

Waist circumference (WC) was measured using a nonstretchable flexible tape in horizontal position, just above the iliac crest, at the end of normal expiration, in the fasting state, with the subject standing erect and looking straight forward and observer sitting in front of the subject. As per the consensus statement provided by Misra et al. in 2009, the risk of developing metabolic syndrome is higher in men with WC ≥36 inches and in females with WC ≥32 inches. Hip circumference was measured as the widest part of the buttocks. WHR was calculated. As per guidelines, we grouped WHR as normal: <0.8, overweight: 0.81–0.85, obese: 0.86–0.9, and morbid obese: >0.9.[4]

BMI is calculated as a ratio of weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). The currently recommended cutoffs of BMI recommended by the World Health Organization include 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 for normal, 25.0–29.9 for overweight, and >30 kg/m2 for obesity. However, Indians have higher percentage body fat, abdominal adiposity at lower or similar BMI levels as compared to white Caucasians. Therefore, as per the consensus statement provided by Misra et al. in 2009, we considered normal BMI as 18.0–22.9 kg/m2, overweight as 23.0–24.9 kg/m2, obesity as >25 kg/m2, and morbid obesity as >30 kg/m2.

Dysglycemia was defined as fasting blood sugar level of >100 mg/dl. Fasting serum insulin was also measured and homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA2-IR) was calculated. Classification was done as normal <2, borderline 2–2.2, moderate 2.2–3, and severe >3.[5]

Lipid profile was measured and a level of triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) <40 mg/dl in males and <50 mg/dl in females was labeled as “deranged.”

OGTT was performed as per standard recommendations. After 2 h, blood glucose of >140 mg/dl was considered as impaired OGTT.

Statistical analysis was done using Statistica version 6 (StatSoft Inc., 2001, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA), SPSS Statistics version 17 (SPSS Inc., 2008, Illinois, Chicago, USA), and GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., 2007, San Diego, California).

Evaluation of normality was done using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (±SD). Categorical data were reported as numbers and percentages. Comparison of numerical variables between the two groups was done using Student's unpaired t-test. Intergroup analysis was done using Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test (two tailed). Odds ratio was calculated for hypertension, deranged lipid profile, dysglycemia, impaired OGTT, HOMA2-IR, serum insulin, BMI, and WHR. Relative risk of developing FAN in the presence of the risk factor was expressed for each of the variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Factors significantly different between cases and controls (at level of P < 0.05) on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate (binary logistic regression) analysis. Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used for the goodness of fit for logistic regression (Step 1, Chi-square 1.868, degrees of freedom 8, and significance 0.985). In logistic regression analysis, data of 213 of 246 individuals were selected for analysis. Thirty-three individuals could not be included because of lack of data pertaining to OGTT.

Results

One hundred and thirty-nine patients were found to have FAN, over a period of 2 years (study duration), of which 123 consented to participate in the study. In addition, 123 age- and sex-matched controls were included in the study. Descriptive variables were normally distributed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. Mean age of the patients with FAN was 38.83 ± 8.62 years. The youngest patient was 22 years old, whereas the eldest one was 61 years old. The male-to-female ratio was 4.35:1 (100 males and 23 females). Ninety-two patients (74.80%) reported outdoor activities of >2 h.

Mean age of onset of the disease was 30.93 ± 8.18 years. The earliest age at which the lesions of FAN began to appear was 13 years. Three patients (2.43%) had features of premature adrenarche, which was statistically insignificant. Forty-one patients (33.33%) reported the presence of similar disease in the family. Twenty-eight patients gave a positive family history of diabetes in the family (22.76%), whereas 34 patients (27.64%) had a family history of dyslipidemia. Thirty-seven patients (30.08%) reported the presence of obesity in their family members. Twenty-nine (23.58%) and twenty-four (19.510%) patients had a history of smoking and consumption of alcohol, respectively.

Hypertension was present in forty cases (32.52%) and 37 controls (30.08%) (Fisher's exact Test, 2-tailed P = 0.783).

As per the WHR, 16 patients (13.00%) were found to be normal (WHR1), 58 patients (47.15%) were overweight (WHR2), 32 patients (26.02%) were obese (WHR3), and 17 (13.82%) were found to have morbid obesity (WHR4). When compared with controls, fifty patients (40.65%) were overweight (WHR2), 17 patients (13.82%) were obese (WHR3), and one patient (0.81%) had morbid obesity (WHR4). Intergroup analysis was done using Pearson's Chi-square test, and the result was statistically significant (P < 0.001), on overall comparison as well as, on comparing WHR2, WHR3, and WHR4 versus WHR1.

BMI was calculated, and 11 patients were normal (BMI1), 85 patients (69.10%) were found to be overweight (BMI2), 24 (19.51%) were obese (BMI3), and 3 (2.44%) were morbidly obese (BMI4). Among the controls, 54 (43.90%) were overweight (BMI2) and 7 (5.69%) were obese (BMI3). Intergroup analysis was done using Pearson's Chi-square test, and the result was statistically significant on overall comparison (P < 0.001). Similar results (P < 0.001) were found on comparing both BMI2 and BMI3 versus BMI1. When BMI4 was compared with BMI1, the P value was found to be 0.005.

Serum insulin was elevated in 45 cases (36.59%) and 20 controls (16.26%). Intergroup analysis was done using Fisher's exact test (2 tailed), and the result was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

The average HOMA2-IR was 4.22 ± 1.79. Nineteen (15.45%) and 58 (47.15%) of the patients had moderate and severe insulin resistance, respectively, as per the HOMA2-IR levels. The average fasting blood sugar level was 109.65% mg.

Dysglycemia was noted in 67 cases (54.47%) and 41 controls (33.33%). Intergroup analysis was done using Fisher's exact test (two tailed), and the result was statistically significant (P = 0.001).

Dyslipidemia was noted in 48 cases (39.02%) and 38 controls (30.89%). Intergroup analysis was done using Fisher's exact test (two tailed) and the result was not statistically significant (P = 0.228).

OGTT was impaired in 55 cases (44.71%) and 25 controls (20.32%). It could not be done in 18 cases and 15 controls. Rest of the cases and controls had normal results. Intergroup analysis was done using Fisher's exact test (2 tailed), and the result was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

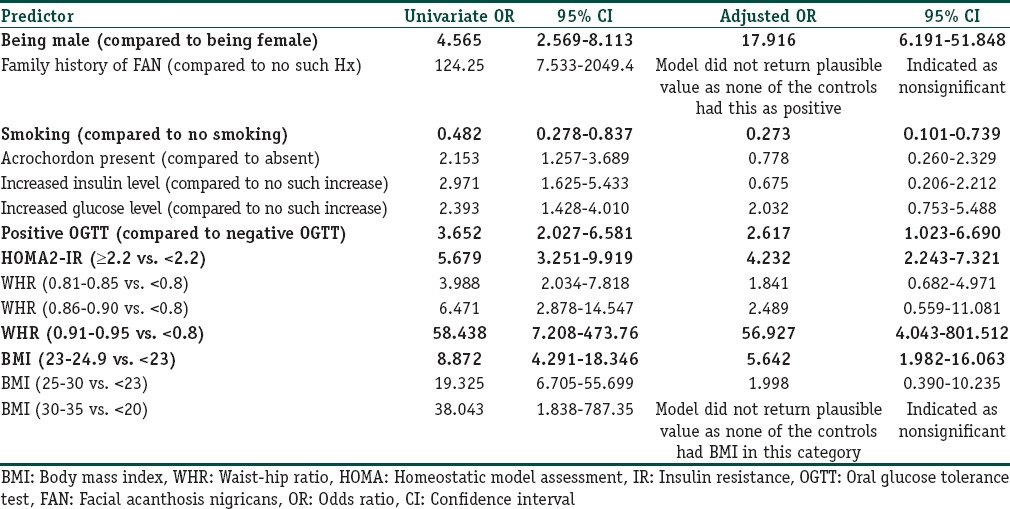

Univariate odds ratio was calculated and factors found have significant differences between cases and controls (at level of P < 0.05) on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate (binary logistic regression) analysis. Factors remaining significant upon logistic regression have been indicated in bold [Table 1].

Table 1.

Odds ratio table. Factors significantly different between cases and controls (at level of p < 0.05) on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate (binary logistic regression) analysis. Factors remaining significant upon logistic regression have been indicated in bold. Note that smoking appears to be a protective factor

Our results show that male sex, positive OGTT, increased WHR, and increased BMI were found to be most significantly related to FAN. Another interesting observation was smoking, which was found to have a protective effect against the development of FAN.

Cutaneous examination findings were noteworthy. Brown-black pigmentation was present in 97 patients (78.86%), and the color was grayish brown in the remaining ones. The most common texture of the skin was noted as dry and rough. Acrochordons were present in 53 patients (43.09%). The most common site of face involved was the forehead and temporal region (85 patients, 69.10%) followed by zygomatic region (71 patients, 57.72%) [Figures 1–5]. Eighteen patients each had periocular and perioral involvement (14.63%). Generalized facial pigmentation was noted in one patient only. Besides, the degree of pigmentation, velvety thickening, and rugosity of the skin was found to increase in proportion to the severity of the disease.

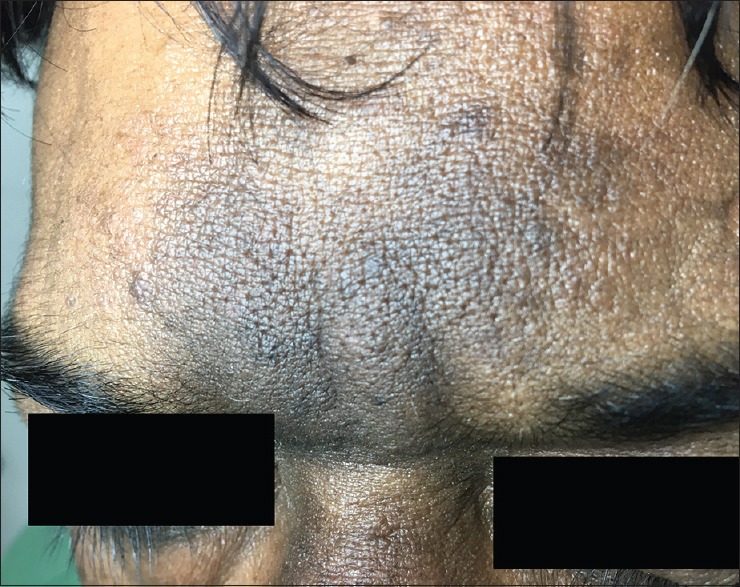

Figure 1.

An obese patient with brown-to-black macular pigmentation with blurred margins. Note the characteristic involvement of the zygomatic area, extending downward. The skin is dry, rough, and verrucous

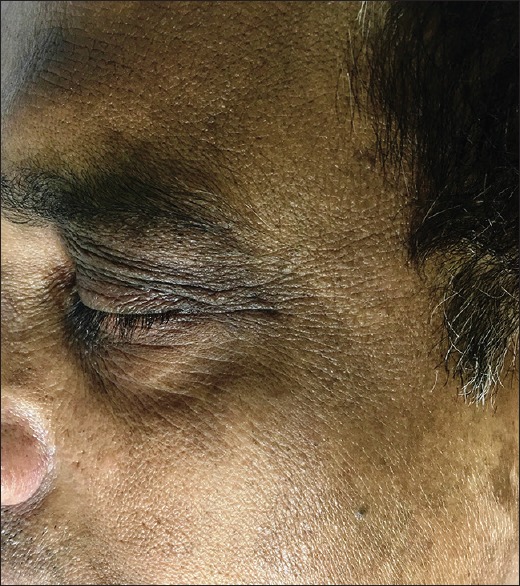

Figure 5.

Clinical picture of a middle aged gentleman with normal BMI with mild lesions of FAN. Involvement of the eyelids can be appreciated

Figure 2.

Same patient with lesions of facial acanthosis nigricans on the other side of the face. Note the severity of the presentation, in terms of intense pigmentation and velvety thickening of the skin

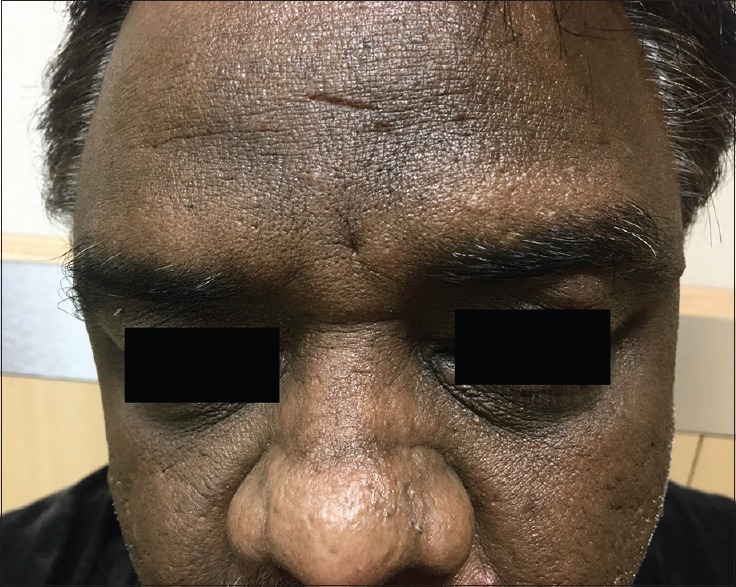

Figure 3.

Classical morphology of facial acanthosis nigricans can be appreciated over the forehead

Figure 4.

An overweight patient with moderate degree of acanthosis nigricans on the forehead

Apart from face, AN was found in 100 patients over the neck (81.30%) followed by 61 (49.59%) over the axilla and 36 (29.26%) over acral regions. Four patients (3.25%) had severe involvement of neck, axilla, groin, and acral regions.

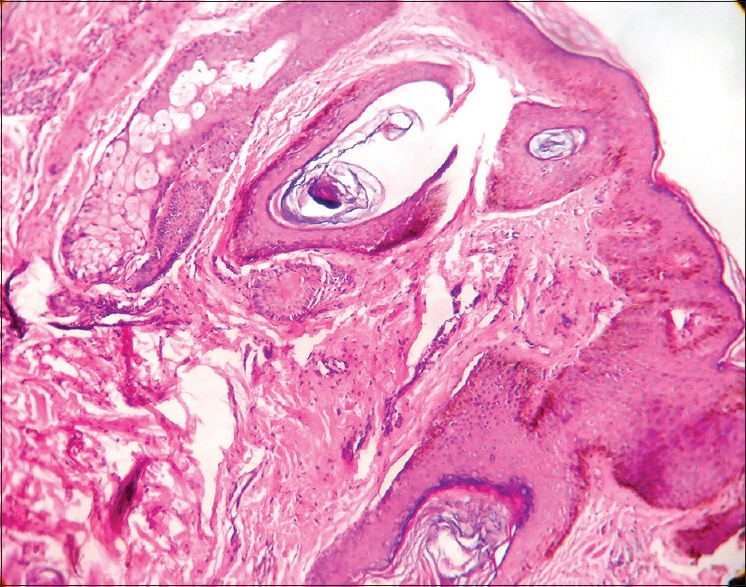

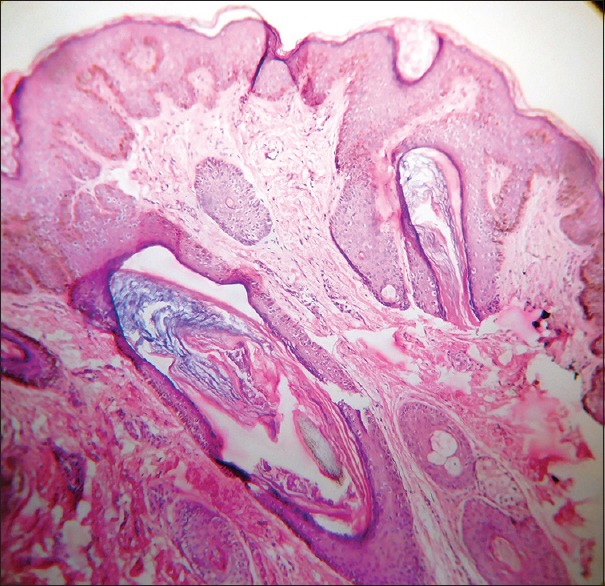

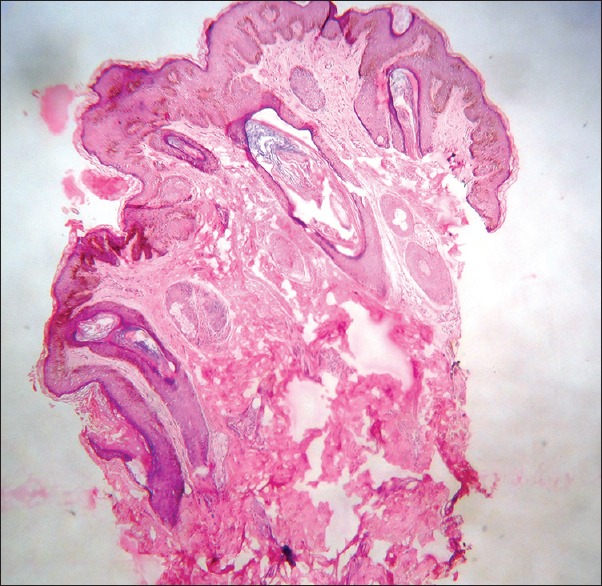

Biopsy was performed in 32 patients. Hyperkeratosis and hypermelanization of the basal layer was the most consistent finding and present in all the biopsies. Papillomatosis was seen in six cases. Follicular plugging was noted in four cases. Interface dermatitis was not found in any case. Dermal melanophages were seen in seven cases [Figures 6–8].

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph showing hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, hypermelanization of basal layer, and follicular plugging (H and E, ×100)

Figure 8.

Photomicrograph showing papillomatosis, follicular plugging and intense melanisation of the basal layer (H&E, 100X)

Figure 7.

Photomicrograph showing hyperkeratosis, mild acanthosis, papillomatosis, follicular plugging and hypermelanisation of the basal layer (H&E, scanner view)

Discussion

AN is clinically manifested as brown to black velvety thickening of the skin of the neck, axillae, groins, inframammary regions, and acral regions. However, FAN characteristically involves the zygomatic and malar areas of the face, the overlying skin being rough, dry, and verrucous. Studies on FAN are lacking, and our study is the first multicentric case–control study.

A study conducted by Verma et al.[3] in 2016, among 102 patients with FAN between 16 and 58 years of age showed a male predilection (2.9:1). There was velvety thickening of the forehead in 59.80%, periorbital darkening in 17.64%, perioral darkening in 12.74%, and generalized darkening in 9.8% of cases. A similar study by Sharquie and Al-Ogaily[6] in 2015, among thirty patients between 16 and 58 years of age showed a male preponderance (male:female ratio: 29:1). The pigmentation was localized to the forehead in 92.3%, temporal areas in 54%, nasolabial folds in 57%, and cheeks in 66.6% of the patients. In our study, the trend of male preponderance was followed, but the ratio was 4.35:1. Verma et al.[3] found 21.5% patients who gave a history of sun exposure for >2 h/day. However, we found 74.80% patients who were exposed to sunlight for >2 h a day. This raises a question regarding the role of sunlight in the etiopathogenesis of FAN. It is too early to comment on this issue, before larger series of cases of FAN with clinico-pathological correlation is published.

We found that the involvement of forehead and temporal region in 69.10% cases and zygomatic area in 57.72% cases. Periocular and perioral involvement each was noted in 14.63% of the patients. AN was found in neck of 81.3% of the patients, axilla in 49.59% of the patients, and axilla in 29.26% of the patients.

In the study by Verma et al.,[3] systemic comorbidities such as hypertension were noted in 49.01%, dyslipidemias in 50.98%, and ischemic cardiac disease in 3.92% cases. We found isolated systolic hypertension in 22.76%, isolated diastolic hypertension in 3.25% cases, and both systolic and diastolic pressures were elevated in 6.50% cases. Dyslipidemia was present in 39.02% of our cases, and we found that patients with dyslipidemia were 1.43 times more prone to develop FAN. Similar to our findings, the study by Sharquie and Al-Ogaily found significantly higher levels of fasting serum triglyceride, total cholesterol, growth hormone, and serum leptin in patients with FAN in comparison with control individuals.

In the study by Sharquie and Al-Ogaily,[6] 33.33% patients were overweight and 53.3% were found to be obese. Verma et al.[3] found that 85.29% of the males were obese and 7.8% were overweight. In case of females, 100% of them belonged to the obese category.

As per WHR, we found that 47.15% of the patients were overweight, 26.02% of the patients were obese, and 13.82% of the patients were found to have morbid obesity. When compared with the controls, the results were found to statistically significant. Besides, it was found that overweight, obese, and morbidly obese patients were 1.8, 2.5, and 56 times more prone to develop FAN, respectively [Table 1]. We calculated the BMI and found that 69.10% of the patients were overweight and 19.51% of the patients were obese (statistically significant results when compared with controls). To note, patients with increased BMI (overweight) were 5.6 times more likely to develop FAN in their life, and those who were classified into obese category as per BMI were two times more likely to develop FAN. On the basis of these results, we propose increased WHR and BMI as reliable predictors of the development of FAN.

In our study, hyperinsulinemia was noted in 60.97% of patients, diabetes in 54.47% of patients, and OGTT was impaired in 44.71% of patients. All of them were found to be significantly higher in comparison to the control group. Therefore, in our study, FAN is well in accordance with the etiopathogenesis of AN (hyperinsulinemia, dysglycemia, increased WHR, and increased BMI).

According to the consensus statement provided by Misra et al., three out of the following five factors need to be present for identification of metabolic syndrome:[4]

Abdominal obesity (>40 inches in males and >34.5 inches in females), non-obligatory criterion

Fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dl

Blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg

Triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl

HDL (<40 mg/dl in males and <50 mg/dl in females).

Consistent with the definition of metabolic syndrome provided by Misra et al., increased WHR, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were significantly higher in the patients with FAN. We can, therefore, conclude that patients presenting with FAN need a thorough workup for underlying metabolic syndrome.

Sharique et al.[6] and Verma et al.[3] attributed the pigmentation to hyperkeratosis, increased melanin, presence of large epidermal melanocytes, and dermal melanin. Consistent with the findings of previous studies, we found thickening of epidermis, increased melanization of epidermis, and presence of dermal melanophages.[7] Papillomatosis was seen in very few cases. This could be attributed to the lesser number of rete pegs in the facial skin as compared to the skin of other parts of body which are typically involved in AN. Earlier authors have proposed the role of elevated growth hormone and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), in the pathogenesis of AN.[8] Besides, Sabater et al. had documented the role of elevated pigment epithelium-derived factor levels in the development of insulin resistance, leading to AN. It was also mentioned that the levels of PEDF and the pigmentation of skin decreased after weight loss.[9]

Limitations

We were unable to perform biopsies in a large number of patients. This is one of the limitations of our study. Further studies on clinicopathological correlations of FAN are required. It is important to find out whether any histological finding has a correlation with the severity of FAN and the underlying systemic diseases. In the same vein, though we recognize that the morphology of FAN is expressed with varying severity, we did not do a grading according to clinical presentation, association with metabolic markers, and histopathological findings. These could certainly be taken up in a future study. Besides, we could not measure the levels of growth hormone and leptin due to logistic difficulties.

Conclusion

FAN is not an uncommon entity. Male patients, those with elevated HOMA2-IR level, positive OGTT, increased WHR, and increased BMI have a significantly higher probability of developing FAN. Smoking has been found to have a protective role against the development of FAN. Further studies should be done to validate this finding. Thus, a patient of FAN should be thoroughly evaluated for underlying systemic illness, even if there are no signs and symptoms of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Institutional.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Facial acanthosis nigricans is a new entity. Male patients, those with elevated HOMA2-IR level, positive oral glucose tolerance test, increased waist hip ratio, and increased body mass index have a significantly higher probability of developing FAN. As per our study, smoking has been found to have a protective role against the development of facial acanthosis nigricans.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Avijit Hazra, Professor, Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata, for his valuable contribution in the statistical analysis of the data. We would also like to extend our heartfelt gratitude towards Dr. Debabrata Bandyopadhyay, Professor and Head, Department of Dermatology, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata for critically reviewing the article and providing erudite comments.

References

- 1.Hisler BM, Savoy LB. Acanthosis nigricans of the forehead and fingers associated with hyperinsulinemia. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1441–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veysey E, Ratnavel R. Facial acanthosis nigricans associated with obesity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:437–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verma S, Vasani R, Joshi R, Phiske M, Punjabi P, Toprani T, et al. A descriptive study of facial acanthosis nigricans and its association with body mass index, waist circumference and insulin resistance using HOMA2 IR. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:498–503. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.193898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misra A, Chowbey P, Makkar BM, Vikram NK, Wasir JS, Chadha D, et al. Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Moran A, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Sinaiko AR, et al. Measurement of insulin sensitivity in children: Comparison between the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp and surrogate measures. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:783–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharquie KE, Al-Ogaily SM. Acanthosis nigricans as a cause of facial melanosis (Clinical and histopathological study) IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;1:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puri N. A study of pathogenesis of acanthosis nigricans and its clinical implications. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:678–83. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.91828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell C. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: A not so sympathetic regulator of insulin resistance? Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:187–90. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31822673f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabater M, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Ortega FJ, Pardo G, Salvador J, Ricart W, et al. Circulating pigment epithelium-derived factor levels are associated with insulin resistance and decrease after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4720–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]