Abstract

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) prior to age 18 was evaluated as a risk factor for adulthood suicide attempt (SA). Archival data from 222 mood-disordered participants were analyzed using multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis. Participants with a youth SA were excluded. The hazards of SA among adult participants with a history of youth NSSI were twice than those of mood-disordered participants without youth NSSI (hazard ratio = 2.00, 95% confidence interval = 1.16−3.44, p = .01). Moreover, participants who had both youth and adult NSSI attempted suicide significantly earlier than participants who began NSSI as an adult. Youth NSSI is associated with persistent, elevated SA risk in adulthood.

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States, claiming over 41,000 lives annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Nonfatal suicide attempts (SAs) occur much more frequently than suicides. Annually, more than one million adults attempt suicide in the United States (Lipari, Piscopo, Kroutil, & Miller, 2015). Despite relatively recent improvements in understanding and treating suicidal behavior, our ability to predict who will attempt or complete suicide and thus intervene to prevent these outcomes remains poor (American Psychiatric Association, 2003; Large, 2010).

Previous SA is one of the most robust and important predictors of subsequent suicidal behavior, including completion (Apter et al., 1991; Beautrais, 2004; Holmstrand, Nimeus, & Traskman-Bendz, 2006; Shearer, Peters, Quaytman, & Wadman, 1988). A clinical implication of this finding is heavy reliance on assessment of past SAs to determine current SA risk (Hawton, 1987; Packman, Marlitt, Bongar, & O’Connor Pennuto, 2004). However, a previous SA is neither a specific nor a sensitive indicator of SA or suicide risk. Thus, other behavioral indicators of SA risk are needed.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as deliberate self-harm that is inflicted without intent to die (Favazza & Rosenthal, 1993), may be one such behavioral indicator of SA risk. In three theories, NSSI is posited to increase subsequent SA risk. In the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior, Joiner, Brown, and Wingate (2005) posit that experiences with NSSI (or other types of “fear-inducing, risky behavior”) change the feelings and sensations associated with subsequent suicidal behavior. In turn, such changes (e.g., the experience of emotional relief as opposed to fear and anxiety during instances of self-injurious behavior) enable the individual to inflict more serious self-injury; that is, attempt suicide, during future crises (Joiner, 2002; Van Orden, Witte, Selby, Bender, & Joiner, 2007; Van Orden et al., 2010). Meanwhile, Whitlock and Knox (2007) propose that suicidal behavior results when stress overwhelms an individual who can no longer cope with negative emotions by engaging in NSSI. Finally, Hamza, Stewart, and Willoughby (2012) describe an integrated model whereby NSSI is linked to SA in three ways. First, SA is posited as an escalation of NSSI which results when interpersonal distress increases; second, an indirect causal link between NSSI and subsequent SA through acquired capability, as described by Joiner et al. (2005), is proposed; and third, other variables, such as depression, are posited to underlie both NSSI and SA and explain their relationship.

In empirical study, NSSI has been associated with SAs, more frequent SAs, and more medically serious suicidal behavior (Zlotnick, Donaldson, Spirito, & Pearlstein, 1997). In fact, studies have found that between 40% and 85% of individuals who engage in NSSI also report a SA (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006; Whitlock & Knox, 2007). A dose effect has also been noted: Individuals with a history of frequent or varied types of NSSI, as compared to infrequent self-injurers or those who use less varied methods, report more suicidal behavior, including more frequent and medically serious SAs (Andover & Gibb, 2010; Brausch & Boone, 2015; Dulit, Fyer, Leon, Brodsky, & Frances, 1994; Victor & Klonsky, 2014; for a review, see Nock et al., 2006; Zlotnick et al., 1997). Victor and Klonsky (2014) draw on Joiner’s interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior to suggest that more frequent NSSI and utilization of more varied NSSI are more strongly associated with SA than less frequent or varied NSSI and that greater exposure to painful experiences, whether because of more method variance or frequency of NSSI, increases the acquired capability for suicide and thus suicidal behavior.

While cross-sectional data have established that NSSI and SA co-occur, only a handful of studies have tested whether NSSI predicts SAs (Ribeiro et al., 2016). Wichstrom (2009) found lifetime NSSI did not predict SA among adolescents followed prospectively for 5 years. Meanwhile, in other studies (Asarnow et al., 2011; Wilkinson, Kelvin, Roberts, Dubicka, & Goodyer, 2011), lifetime NSSI or NSSI in the month prior to study entry was shown to predict SA, independently of suicidal ideation or attempt, over a 6-month follow-up among depressed adolescent outpatients in treatment. Similar findings are also reported among adolescent community members, adolescent and emerging adult offspring who are at high risk for suicidal behavior given their parents’ clinical history, and active duty soldiers who are in mental health treatment. Past-year or lifetime NSSI predicts SA over 2- to 4-year follow-up in these groups independent of recent suicidal ideation or attempt (Bryan, Bryan, May, & Klonsky, 2015; Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Young-McCaughon, & Peterson, 2015; Cox et al., 2012; Guan, Fox, & Prinstein, 2012). A few studies have excluded individuals with a history of both NSSI and SA when testing NSSI as a risk factor for subsequent SA and found similar results. For instance, in college students, recurrent lifetime NSSI precedes and elevates risk for SA (Whitlock et al., 2013).

Thus, taken together, there is evidence that NSSI predicts SA in adolescence and emerging adulthood and there are cross-sectional data and theories associating NSSI with SAs. Here, we extend previous studies and compare SA rates among adult participants with a mood disorder who did and did not endorse youth (i.e., prior to age 18) NSSI. We excluded individuals who also had a history of SA during their youth to ensure that the NSSI preceded the SA and that we were not actually modeling risk for the group of individuals who had a history of both NSSI and SA. This group has been found to be at increased risk for SA compared to individuals who engage in NSSI or suicidal behavior (e.g., Bryan, Bryan, et al., 2015; Bryan, Rudd, et al., 2015). Based on previous findings showing NSSI is associated with and predicts SA, we posited that youth NSSI would increase risk of adult SA in our sample. Studies ensuring temporal precedence of NSSI compared to SA in determining SA risk associated with NSSI are scarce, limiting understanding of whether NSSI predicts SA (Victor & Klonsky, 2014). Further, previous studies have not tested whether youth who engage in NSSI are at risk for SA in adulthood (Hamza et al., 2012). Thus, our study adds to the literature by testing whether youth NSSI results in long-term elevation of SA risk. We also hypothesized that youth NSSI would predict SA during adulthood independent of risk factors that differentiate SA with and without NSSI; for example, aggression (e.g., Guertin, Lloyd-Richardson, Spirito, Donaldson, & Boergers, 2001). Finally, in an attempt to clarify whether continuation of NSSI into adulthood changes the relationship between youth NSSI and adult SA, we compared individuals who engaged in youth NSSI and/or adult NSSI to individuals without a history of NSSI. No prior studies to our knowledge have tested whether cessation or maintenance of adult NSSI among youth who engage in NSSI influences risk of adult SA.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

This study used archival data on 222 adult participants with major depressive disorder (71.5%, n = 158) or bipolar disorder (BPD; 28.5%, n = 63), per standardized research assessment, who presented at a large psychiatric research center in the United States. Accordingly, approval for this study was granted by the local institutional review board. All individuals whose data were included in this study gave their informed consent prior to participating. Exclusion criteria for the larger study included a current substance use or medical disorder that might explain mental health symptomatology and/or decrease accurate understanding of the clinical picture. Because we were interested in determining whether youth NSSI increased the risk of subsequent SA, we excluded an additional 50 participants who reported a SA before age 18 and thus for whom we could not ensure that NSSI occurred prior to SA.

At intake, the average age of participants was 40.9 years (SD = 11.5 years, range = 18− 72). Fifty-seven percent of participants were female (n = 126). Over 80% of participants identified their race as Caucasian (n = 171), and 16% identified their ethnicity as Hispanic (n = 34). The majority of participants (74.3%, n = 165) were single and reported that they had completed high school (96.4%, n = 214). Most participants did not have children (57.7%, n = 128). Thirty-nine percent of participants (n = 86) had a lifetime anxiety disorder; 35% had a lifetime substance use disorder (n = 78); 20% had a comorbid borderline personality disorder (n = 43); 17% had lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 38); and 7% had a lifetime eating disorder diagnosis (n = 16).

Clinical and demographic information was collected during semistructured interviews and from self-report assessments that were completed at intake. Follow-up data on SAs that were collected at assessments completed 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years after intake were also used. All interviews were completed by trained masters- and doctoral-level clinicians. Clinical ratings of diagnoses and SAs were discussed and agreed upon at biweekly consensus meetings staffed by clinical researchers.

Measures

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)

The BIS-11 is a 30-item self-report measure of impulsivity (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more frequent nonplanning impulsiveness, motor impulsivity, and cognitive impulsivity. The BIS-11 has been found to have good psychometric properties (Enticott, Ogloff, & Bradshaw, 2006; Patton et al., 1995; Swann, Bjork, Moeller, & Dougherty, 2002). The internal reliability of the BIS-11 in this sample was .69, indicating the scale maintained adequate internal consistency.

Brown-Goodwin Lifetime History of Aggression (BGAH)

The BGAH is an 11-item clinician-administered assessment that measures aggressive behavior across a variety of situations that are directed toward people or objects (Brown, Goodwin, Ballenger, Goyer, & Major, 1979). Items are scored on a scale of 1 (never) to 4 (often), with higher item scores indicating more frequent perpetration of the particular behavior that is referenced in the item (e.g., temper tantrums, physical fights). Respondents are asked each item three times. They respond first to indicate the frequency of perpetration of the behavior in childhood (i.e., aged 12 years or younger). Then, they are asked about their engagement in the behavior during adolescence (ages 13– 18 years) and adulthood (ages 18 years and older). Only the maximum rating across all three periods is included in the total score. In this study, the last item about nonsuicidal “self-violence” was used to assess NSSI. It reads, “Have you ever inflicted violence on yourself? (Only rate non-suicidal behavior, e.g., self-mutilation, head banging, wrist scratching, minor burns, etc., which has not been scored as a suicide attempt.) When did it happen? Describe.” To avoid spuriously high correlations between the BGAH total score and our measure of NSSI, this item was omitted from the total aggression score. Further, only aggressive behaviors during childhood and adolescence (i.e., prior to age 18), and not those that occurred during adulthood were considered in the aggression score. That is, only the maximum rating during childhood or adolescence on each of 10 BGAH items was included in the total aggression score that was reported in this study. Thus, total BGAH scores ranged from 10 to 40, with higher scores representing a history of more frequent childhood or adolescent aggressive behavior. Ratings from the NSSI item were dichotomized to represent, any, regardless of frequency, childhood or adolescent NSSI versus no childhood or adolescent NSSI. We also dichotomized ratings of the frequency of NSSI on the adulthood BGAH NSSI item to capture engagement in any adulthood NSSI, as this variable was included in follow-up analyses aimed at specifying whether cessation or continuation of NSSI in adulthood changed the relationship between youth NSSI and adult SA and the relative risk of SA to participants who first initiated NSSI in adulthood. The BGAH has been found to have good construct validity and interrater reliability (Kruesi et al., 1995). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the BGAH was good (α = .81).

Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI)

The BDHI is an often-used 75-item self-report measure of trait hostility (Buss & Durkee, 1957). The BDHI uses a true–false response option format to assess attitudinal and motor hostility. The BDHI has shown fairly good test–retest reliability (Biaggio, Sapplee, & Curtis, 1981). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the BDHI in this study was .86.

Columbia Suicide History Form (CSHF)

CSHF is a clinician-administered assessment used to collect information about interviewees’ lifetime SAs and acts of deliberate self-injury that involve some intent to die (Oquendo, Halberstam, & Mann, 2003). For this study, a patient was classified as a suicide attempter if, per consensus using all available data sources, he or she attempted suicide on or after age 18, regardless of whether the SA occurred during the study or before it (and was thus recorded at intake).

Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I and II (SCID-I and SCID-II)

The SCID-I and SCID-II are semistructured clinical interviews that are used to aide researchers and clinicians in making reliable and accurate DSM diagnoses (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990; Gibbon, Spitzer, & First, 1997). As with the CSHF, lifetime best-estimate diagnoses were made by consensus using SCID and all other available data.

Demographic information, including age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, number of children, education, and childhood sexual abuse history (yes or no per report during a semistructured clinical interview), was also collected.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, www.sas.com). For the bivariate analyses of this study, participants were divided into two groups. One group was comprised of individuals with youth NSSI (14.0%, n = 31); the other group included individuals who did not engage in NSSI in their youth (86%, n = 191). Two-sample t tests and Mann–Whitney U- tests were run to identify group differences on continuous demographic and clinical variables. Chi-square analysis and Fisher’s exact test were used to test for differences between the groups on categorical variables such as gender and ethnicity. Next, youth NSSI along with the other clinical variables found to differ between individuals with and without youth NSSI in bivariate analyses were entered into a Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Only adult SAs (attempts occurring at age 18 or older) were counted as events. Finally, adult (i.e., age 18 or older) SA rates for youth with and without NSSI were illustrated using survival curves. In follow-up analysis to determine the impact of adult NSSI on the relationship between youth NSSI and adult SA, Cox regression analysis was repeated using four strata defined by the combination of youth and/or adult NSSI, and SA rates for each of these four groups were plotted as survival curves.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical information for the groups with and without youth NSSI are presented in Table 1. Individuals with youth NSSI reported more youth aggression than individuals without youth NSSI. At intake, participants with youth NSSI were younger than participants without youth NSSI. As this age difference between groups would bias estimates toward detecting increased SA risk among individuals without youth NSSI (as they would have a longer period at risk to attempt suicide), if this age difference between groups biased estimates at all, this difference was not further considered or controlled for in the analyses.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Participants with and without Youth NSSI

| Variables | Youth NSSI

|

No Youth NSSI

|

Analysis

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | N | n with characteristic | % | N | n with characteristic | % | χ2 | df | p |

| White | 29 | 23 | 79.3 | 174 | 148 | 85.1 | 0.15a | – | .42 |

| Hispanic | 30 | 6 | 20.0 | 189 | 28 | 14.8 | 0.15a | – | .43 |

| Female | 31 | 21 | 67.7 | 191 | 105 | 55.0 | 1.77 | 1 | .18 |

| Suicidal acts first-degree relative | 30 | 7 | 23.3 | 188 | 28 | 14.9 | 0.10a | – | .28 |

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | t or U | p | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Age | 31 | 35.4 | 11.3 | 191 | 41.8 | 11.3 | 2.91 | 220 | .004 |

| Self-reported childhood sexual abuse | 31 | 4 | 12.9 | 190 | 19 | 10.0 | 0.24 | 1 | .62 |

| Clinical characteristics | N | n with characteristic | % | N | n with characteristic | % | χ2 | df | p |

|

| |||||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 31 | 11 | 35.5 | 191 | 52 | 27.4 | 0.86 | 1 | .35 |

| Comorbid anxiety disorder | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 191 | 70 | 36.7 | 2.52 | 1 | .11 |

| Comorbid PTSD | 31 | 7 | 22.6 | 191 | 31 | 16.2 | 0.76 | 1 | .39 |

| Comorbid eating disorder | 31 | 4 | 14.0 | 191 | 12 | 6.3 | 0.11a | – | .25 |

| Comorbid substance use disorder | 31 | 11 | 35.5 | 191 | 67 | 35.1 | <0.01 | 1 | .97 |

| Comorbid BPD | 30 | 10 | 33.3 | 187 | 33 | 17.7 | 4.00 | 1 | .05 |

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | t or U | p | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Youth aggression | 31 | 18.7 | 6.2 | 191 | 15.2 | 4.6 | Z = 3.22 | .001 | |

| Hostility | 27 | 38.5 | 12.1 | 177 | 35.2 | 12.0 | 1.31 | 202 | .19 |

| Impulsivity | 26 | 56.7 | 16.7 | 179 | 53.3 | 17.9 | 0.89 | 203 | .38 |

Note. Two-tailed. PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; BPD, borderline personality disorder.

Fisher’s exact test.

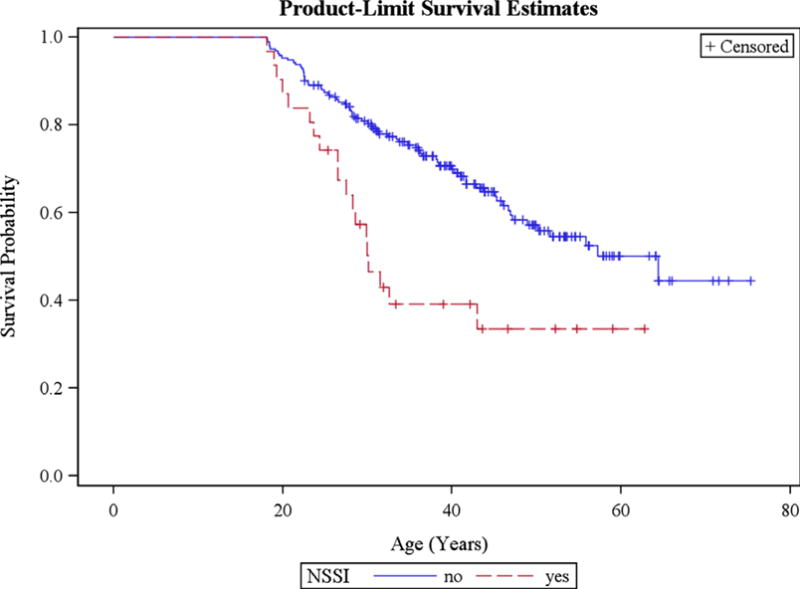

The results of the multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis showed that only a history of youth NSSI (hazard ratio = 2.00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.16−3.44, p = .01), and not youth aggression, increased risk of adult SA. Further, tests of the proportional hazards assumption indicated the risk for adulthood SA due to youth NSSI did not vary over time (i.e., across adulthood age; p = .15). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the cumulative unadjusted proportion (over time in adulthood) of participants who did not attempt suicide by history of youth NSSI.

Figure 1.

Cumulative proportion of participants who did not attempt suicide during adulthood by history of youth NSSI. Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival functions. Log-rank rank χ2 for strata homogeneity = 11.23, p = .0001. Mean age of suicide attempt in patients without youth NSSI = 50.07 years (SD = 1.33). Mean age of suicide attempt in patients with youth NSSI = 32.49 years (SD = 1.72). The results of the Cox proportional hazard analysis unadjusted for youth aggression showed hazard ratio for youth NSSI = 2.33, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.40− 3.88, p = .001. NSSI, nonsuicidal self-injury.

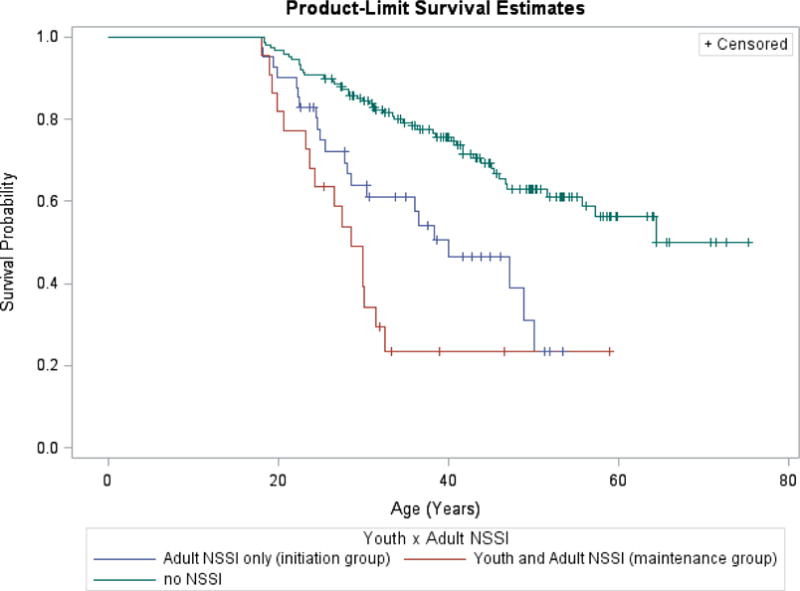

Because we were interested in specifying whether cessation or continuation of NSSI in adulthood changed the relationship between youth NSSI and adult SA as well as the relative risk of SA to those who initiated NSSI in adulthood, we next compared survival curves among groups defined by their history of youth and adult NSSI. In this analysis, there was a significant difference between groups (log-rank rank χ2 test for strata homogeneity = 34.31, p < .0001). Participants who had both youth and adult NSSI attempted suicide significantly earlier than participants who began NSSI as an adult (mean age of SA in participants with youth and adult NSSI = 27.2, SD = 1.14 years versus mean age of SA in participants with adult NSSI only = 37.84, SD = 2.02 years). Individuals who engaged in neither youth nor adult NSSI attempted suicide, on average, at 52.19 years (SD = 1.44 years). Only nine individuals ceased NSSI in adulthood. These individuals were excluded from the analysis given their small numbers and thus concern about the stability of statistics derived from their data (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of participants who did not attempt suicide during adulthood by history of youth and adulthood NSSI. Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival functions. NSSI, nonsuicidal self-injury.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that a history of youth NSSI places individuals at greater risk for SA throughout adulthood. Moreover, individuals who maintain NSSI into adulthood are at greater risk for adult SA than individuals who begin NSSI in adulthood or do not engage in NSSI.

This study is among the first to document a temporal relationship between NSSI and SA such that youth NSSI elevates risk for adult SA. Findings from this study add to findings relating NSSI to SA among adolescents and adults (Brausch & Boone, 2015; Guertin et al., 2001; Hamza et al., 2012; Nock et al., 2006; Victor & Klonsky, 2014; Whitlock & Knox, 2007). Findings from this study align with findings from a handful of prospective studies showing NSSI robustly predicts SA, even when prior SA and other clinical risk factors for SA are controlled in multivariate prediction models of SA (Asarnow et al., 2011; Bryan, Bryan, et al., 2015; Bryan, Rudd, et al., 2015; Cox et al., 2012; Guan et al., 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2016; Whitlock et al., 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2011). Our study extends these findings by demonstrating youth NSSI precedes adulthood SA and elevates risk for it throughout adulthood.

The prevalence of youth NSSI reported by adult participants with mood disorder in our sample was 14%. This prevalence rate is lower than those rates observed among referred adolescents with mood disorder in some (Wilkinson et al., 2011) but not all studies (Brent et al., 2009), where rates of 37% and 9%, respectively, were observed. On the one hand, our prevalence rate may be higher than some observed rates because we assessed for and considered any NSSI over a longer time period than past studies; that is, childhood and adolescence to age 18, as compared to 12 weeks or 1 year during adolescence. On the other hand, compared to studies of adolescents receiving mental health treatment and studies estimating current and past rates of NSSI among adolescent community members, the prevalence of youth NSSI observed in our sample was low (Jacobson & Gould, 2007; Nock, 2010). This may accurately reflect youth NSSI among participants included in our study, or this rate may underestimate actual youth NSSI among sample members. Brent et al. (2009) have found that consistent, systematic monitoring, as compared to reliance on a single, retrospective report, increases the accuracy of NSSI assessment. Our collection of NSSI data was completed at one time point and required adults of average age 40 to recall behavior that occurred in their youth.

In our sample, youth aggression differed among participants reporting youth NSSI and participants without youth NSSI. Previous findings regarding the association between trait aggression and NSSI are limited, equivocal, and seem dependent upon the population, the informant (e.g., parent vs. self), and the type of aggression (e.g., verbal vs. physical) studied (Claes, Vandereycken, & Vertommen, 2003; Victor, Feske, & Klonsky, 2011). For instance, aggression and NSSI have been associated among adolescent psychiatric patients. Among adults with BPD or another nonpsychotic disorders, however, only self-directed aggression and NSSI were related (Victor et al., 2011). Aggression is, however, robustly associated with SA and deliberate self-harm (a category of behavior used by European researchers that includes both NSSI and SA; Keilp et al., 2006; Koelch, Plener, Schlanser, Doelitzsh, & Schmid, 2011). Additionally, anger, a related concept, has been readily associated with NSSI (Claes et al., 2003; Glassman, Weirerich, Hooley, Deliberto, & Nock, 2007; Jacobson & Gould, 2007). In one study of adolescent attempters, for example, adolescent attempters with a history of NSSI reported more anger than adolescent attempters without a history of NSSI (Guertin et al., 2001). Thus, our findings add support to findings that show a relationship between NSSI and aggression in youth.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although we found youth NSSI placed participants with mood disorder at higher risk for SA throughout adulthood and those who engaged in both youth and adult NSSI were at higher adult SA risk than those with a history of only adult NSSI or no lifetime NSSI, limits to our data preclude further understanding of how and for whom youth NSSI escalates to adult SA. In fact, fully 39% of sample members who engaged in youth NSSI did not make a SA in adulthood. Others (Giletta et al., 2015; Scott, Pilkonis, Hipwell, Keenan, & Stepp, 2015) have found NSSI in combination with suicidal ideation compared to NSSI alone increases risk for subsequent SA. In fact, in a meta-analytic examination of correlates of SA among individuals who engage in NSSI, Victor and Klonsky (2014) found suicidal ideation was the strongest clinical or demographic correlate of SA among individuals who engage in NSSI. Thus, the presence of co-occurring suicidal ideation may moderate the relationship between NSSI and SA. Studies of mediators or third variables that explain the relationship between youth NSSI and adult SA are also needed. In theoretical models linking SA to NSSI difficulties in emotion regulation are posited to underlie both behaviors. Thus, emotion dysregulation could be investigated as a third variable that could explain why or for whom NSSI leads to increased SA risk. Interestingly, we did not find differences in co-occurring disorders, including borderline personality disorder, between sample members who did and did not report youth NSSI. In prior studies, associations between borderline personality disorder and both youth NSSI and adult SA are consistently found (Jacobson & Gould, 2007; Maris, Berman, & Silvermann, 2000; Nock et al., 2006). Future studies are needed to test the role of borderline personality disorder in the pathway between youth NSSI and adult SA.

Further, as 75% of our sample was aged 50 or younger, estimates of SA risk or survival probability in older age are likely unstable. Thus, future studies with older adult samples are needed to confirm understanding of SA risk following NSSI among older adults.

Our sample included participants with mood disorder. Many also had comorbid anxiety, substance use, and/or borderline personality disorders. Thus, these findings may not generalize to individuals with other disorders where NSSI can also occur, for such as psychotic disorders. The largely retrospective nature of the NSSI and SA data used in our study is another limitation as memory biases may impact the validity of retrospective reports (Schwarz & Sudman, 1994). In particular, adults who continue to engage in self-directed violence into adulthood (i.e., attempt suicide) may have a greater ability to recall self-directed violence in childhood and adolescence (i.e., NSSI) than adults who do not.

A final limitation was our measure of NSSI. We used one item from the BGAH to understand NSSI in youth. Despite concerns that using a single question to understand NSSI may capture clinically insignificant or nonmeaningful NSSI, a single question is often used to capture NSSI in studies (e.g., Brausch & Boone, 2015; Claes et al., 2010). Moreover, single self-report item assessments of SA have been found to have good sensitivity compared to multi-item self-report assessments (Millner, Lee, & Nock, 2015). Nonetheless, longitudinal studies using multiple-item rating scales to assess NSSI are needed to confirm our findings.

Despite these limitations, our study is among the first to elucidate a temporal relationship between NSSI and SA whereby youth NSSI precedes and elevates risk for SA in mood-disordered adult participants throughout adulthood. Moreover, we showed maintenance of NSSI in adulthood is associated with greater adult SA risk than initiation of NSSI in adulthood. This study addressed a significant gap in the literature. Previous studies have not provided information that shows long-term elevations in adulthood SA risk for youth who engage in NSSI.

Clinical Implications

Our findings suggest that youth NSSI is a risk factor for SA throughout adulthood. Moreover, persistence of NSSI in adulthood places an individual at greater risk for adult SA than initiation of NSSI in adulthood. Thus, findings from our study suggest the assessment of NSSI, including distal youth NSSI, may aide in identifying individuals at risk for adult SA. NSSI occurs at rates of up to 37% among referred children, 60% in clinical adolescent populations, and 45% among community adolescents (Espostio-Smythers et al., 2010; Jacobson & Gould, 2007; Nock, 2010). Further, findings from Cloutier, Martin, Kennedy, Nixon, and Muehlenkamp (2010) indicate adolescents who engage in NSSI present at emergency departments in larger proportions than adolescents who make SAs. Thus, NSSI seems a potentially identifiable risk factor for SA. A number of psychometrically sound measures such as the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (Nock, Holmberg, Photos, & Michel, 2007) and the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (Linehan, Comtois, Brown, Heard, & Wagner, 2006; Linehan, Comtois, Murray, et al., 2006) are available to guide clinical assessment of NSSI.

Therapeutic techniques targeting NSSI are available. Behavioral chain and solution analysis, in the style of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993), are two such techniques that may prove effective in reducing NSSI (e.g., Linehan, Comtois, Brown, et al., 2006; Linehan, Comtois, Murray, et al., 2006). Further, findings from a recent study of adolescents suggested NSSI in the context of depression, unlike suicidal behavior, decreased when depression was treated (Wilkinson et al., 2011). Thus, promising options exist to reduce NSSI and perhaps prevent the sequelae of NSSI.

Because individuals with histories of both SA and NSSI have more maladaptive personality traits, coping skills, and mental health difficulties than individuals with either SA or NSSI (Claes et al., 2010; Cloutier et al., 2010; Victor & Klonsky, 2014), assessing NSSI among suicidal patients may also be important for reducing distress and mitigating poor outcomes. In fact, individuals with a history of NSSI and SA, as compared to individuals with a history of either SA or NSSI, display more chronic and frequent suicidal ideation and SAs, underestimate the lethality of subsequent attempts, and discount the finality of their actions (Cloutier et al., 2010; Giletta et al., 2015; Muehelenkamp & Gutierrez, 2007; Scott et al., 2015; Stanley, Gameroff, Michalsen, & Mann, 2001). Thus, careful assessment of NSSI among suicidal adult patients may prove important for accurate identification of those at highest risk for suicide among this high-risk group.

Contributor Information

Megan S. Chesin, Department of Psychology, William Paterson University, Wayne, NJ, and Molecular Imaging and Neuropathology Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

Hanga Galfavy, Molecular Imaging and Neuropathology Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

Cemile Ceren Sonmez, Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Amanda Wong, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NY, USA.

Maria A. Oquendo, Molecular Imaging and Neuropathology Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

J. John Mann, Molecular Imaging and Neuropathology Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

Barbara Stanley, Molecular Imaging and Neuropathology Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. 2003 Retrieved June 29, 2015, from https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/suicide.pdf. [PubMed]

- Andover MS, Gibb BE. Non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide, and suicidal intent among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2010;178:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apter A, Kotler M, Sevy S, Plutchik R, Brown SL, Foster H, et al. Correlates of risk of suicide in violent and nonviolent psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:883–887. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: Findings from the TORDIA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL. Further suicidal behavior among medically serious suicide attempters. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2004;34:1–11. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.1.27772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaggio MK, Sapplee K, Curtis N. Reliability and validity of four anger scales. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1981;45:639–648. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4506_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Boone SD. Frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: Differences in suicide attempts, substance use, and disordered eating. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2015;45:612–622. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, Asarnow J, Spirito A, Ritz L, et al. Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:418–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Research. 1979;1:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, May AM, Klonsky ED. Trajectories of suicide ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury, and suicide attempts in a nonclinical sample of military personnel and veterans. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2015;45:315–325. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd MD, Wertenberger E, Young-McCaughon S, Peterson A. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a prospective predictor of suicide attempts in a clinical sample of military personnel. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2015;59:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21:343–349. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQUARS injury mortality statistics. 2015 Retrieved June 29, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leadingcauses.html.

- Claes L, Muehlenkamp J, Vandereycken W, Hamelinck L, Martens H, Claes S. Comparison of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in patients admitted to a psychiatric crisis unit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Eating-disordered patients with and without self-injurious behaviours: A comparison of psychopathological features. European Eating Disorders Review. 2003;11:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier P, Martin J, Kennedy A, Nixon MK, Muehlenkamp JJ. Characteristics and co-occurence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behaviours in pediatric emergency crisis services. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2010;39:259–269. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LJ, Stanley BH, Melhem NM, Oquendo MA, Birmaher B, Burke A, et al. A longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury in offspring at high risk for mood disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:821. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulit RA, Fyer MR, Leon AC, Brodsky BS, Frances AJ. Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1305–1311. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.9.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticott PG, Ogloff JRP, Bradshaw JL. Associations between laboratory measures of executive inhibitory control and self-reported impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Espostio-Smythers C, Goldstein T, Birmaher B, Goldstein B, Hunt J, Ryan N, et al. Clinical and psychosocial correlates of non-suicidal self-injury within a sample of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;125:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR, Rosenthal RJ. Diagnostic issues in self-mutilation. Hospital & Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:134–140. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, First MB. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders: SCID-II. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Giletta M, Prinstein MJ, Abela JR, Gibb BE, Barrocas AL, Hankin BL. Trajectories of suicide ideation and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents in mainland China: Peer predictors, joint development, and risk for suicide attempts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:265. doi: 10.1037/a0038652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman LH, Weirerich MR, Hooley JM, Deliberto TL, Nock MK. Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2483–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Fox KR, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a time-invariant predictor of adolescent suicide ideation and attempts in a diverse community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:842. doi: 10.1037/a0029429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin T, Lloyd-Richardson E, Spirito A, Donaldson D, Boergers J. Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Stewart SL, Willoughby T. Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature and an integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32:482–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K. Assessment of suicide risk. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:145–153. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrand C, Nimeus A, Trask-man-Bendz L. Risk factors of future suicide in suicide attempters: A comparison between suicides and matched survivors. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;60:162–167. doi: 10.1080/08039480600583597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CM, Gould M. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11:129–147. doi: 10.1080/13811110701247602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. The trajectory of suicidal behavior over time. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2002;32:33–41. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.33.22187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Brown JS, Wingate LR. The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:287–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Oquendo MA, Brodsky B, Ellis SP, Stanley B, et al. Aggressiveness, not impulsiveness or hostility, distinguishes suicide attempters with major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1779–1788. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelch M, Plener PL, Schlanser S, Doelitzsh C, Schmid M. Deliberate self harm in Swiss youths in residential care; Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of Self-Injury; New York, NY. 2011. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Kruesi MJP, Hibbs ED, Hamburger SD, Rapoport JL, Keysor CS, Elia J. Measurement of aggression in children with disruptive behavior disorders. In: Hillbrand M, Pallone NJ, editors. The psychobiology of aggression. Binghamton, NY: Haworth; 1995. pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Large MM. No evidence for improvement in the accuracy of suicide risk assessment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198:604. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e9db3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner A. Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): Development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:303–312. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–768. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari R, Piscopo K, Kroutil LA, Miller GK. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR2-2014/NSDUH-FRR2-2014.pdf.

- Maris RW, Berman AL, Silver-mann MM. Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. New York, NY: Guilford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Lee MD, Nock MK. Single-item measurement of suicidal behaviors: Validity and consequences of misclassification. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehelenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1080/13811110600992902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Risk factors for suicidal behavior. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2003;22:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Packman WL, Marlitt RE, Bongar B, O’Connor Pennuto T A comprehensive and concise assessment of suicide risk. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2001;22:667–680. doi: 10.1002/bsl.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine. 2016;46:225–236. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Sudman S. Autobiographical memory and the validity of retrospective reports. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scott LN, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, Keenan K, Stepp SD. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation as predictors of suicide attempts in adolescent girls: A multi-wave prospective study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2015;58:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer SL, Peters CP, Quaytman MS, Wadman BE. Intent and lethality among female borderline inpatients. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145:1424–1427. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.11.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for the DSM-III-R (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Gameroff MJ, Michal-sen V, Mann JJ. Are suicide attempters who self-mutilate a unique population? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:427–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM. Two models of impulsivity: Relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:988–994. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Bender TW, Joiner TE. Suicidal behavior in youth. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BJ, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 441–465. [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, Feske U, Klonsky ED. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. New York, NY: 2011. Jun, Which types of aggression are elevated among those who engage in non-suicidal self-injury? [Google Scholar]

- Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Correlates of suicide attempts among self-injurers: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Knox KL. The relationship between self-injurious behavior and suicide in a young adult population. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:634–640. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Muehlenkamp J, Ecken-rode J, Purington A, Abrams GB, Barreira P, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a gateway to suicide in young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrom L. Predictors of non-suicidal self-injury versus attempted suicide: Similar or different? Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13(2):105–122. doi: 10.1080/13811110902834992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of SAs and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Donaldson D, Spirito A, Pearlstein T. Affect regulation and suicide attempts in adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:793–798. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]