Abstract

Current challenges in early detection, limitations of conventional treatment options, and the constant evolution of cancer cells with metastatic and multi-drug resistant phenotypes require novel strategies to effectively combat this deadly disease. Nanomedical technologies are evolving at a rapid pace and are poised to play a vital role in diagnostic and therapeutic interventions - the so-called “theranostics” – with potential to advance personalized medicine. In this regard, nanoparticulate delivery systems can be designed with tumor seeking characteristics by utilizing the inherent abnormalities and leaky vasculature of solid tumors or custom engineered with targeting ligands for more specific tumor drug targeting. In this review we discuss some of the recent advances made in the development of multifunctional polymeric nanosystems with an emphasis on image-guided drug and gene delivery. Multifunctional nanosystems incorporate variety of payloads (anticancer drugs and genes), imaging agents (optical probes, radio-ligands, and contrast agents), and targeting ligands (antibodies and peptides) for multi-pronged cancer intervention with potential to report therapeutic outcomes. Through advances in combinatorial polymer synthesis and high-throughput testing methods, rapid progress in novel optical/radiolabeling strategies, and the technological breakthroughs in instrumentation, such as hybrid molecular and functional imaging systems, there is tremendous future potential in clinical utility of theranostic nanosystems.

Keywords: Drug delivery, image-guided delivery, liposomes, multifunctional nanosystems, personalized medicine, polymeric nanoparticles, theranostics, tumor targeting

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Cancer Challenges

The diagnosis and treatment of many cancers stills remains elusive and a major barrier to effective clinical outcomes. A recent review by Hanahan and Weinberg [1] elucidates the “hallmark” characteristics of cancers and the deregulation and signaling pathways that are involved in the development and progression of tumors. Cancer cells are known to possess unique characteristics of dividing and proliferating rapidly, resisting cell death or apoptosis, and having devastating invasive potentials. Also, tumor cells have the ability to infiltrate surrounding normal tissues or penetrate into lymphatics and/or blood vessels enabling them to circulate (called circulating tumor cells) and migrate to multiple distant sites or organs, forming secondary tumors [1, 2]. This process called “tumor metastasis” often occurs at an advanced stage of the disease and is generally beyond the scope of surgical resection or other forms of treatment, largely responsible due to the failure in early detection and management of the disease. Even in the case where surgical resection is a viable option, there is always a high risk of relapse of the disease due to existence of microscopic subpopulations of recalcitrant tumor cells that are speculated to possess “stem cell like” characteristics [3], that play a key role in self-renewal and formation of new types of tumors [4]. Apart from these inherent destructive qualities, tumor cells have the capability to reprogram themselves to suite various demanding and testing conditions of the tumor microenvironment, such as the ability to survive (and often thrive) in highly acidic pH [5, 6] and very low oxygen or hypoxic conditions [7–10]. Moreover, most tumors cells acquire resistance or become insensitive to a broad spectrum of structurally and functionally different (and otherwise effective) anticancer agents on prolonged exposure; a process known as acquired tumor multi-drug resistance (MDR) [11–13]. The micro-environmental selection pressures that leads to the acquired MDR phenotype is well known to be a major reason for drug treatment failure in cancer patients [14]. Also, the genomic instability in cancers gives rise to accumulation of mutations and this instability leads to intratumoral (i.t.) heterogeneity in successive generations of tumors [15]. These ever-changing and unpredictable genetic mutations in cancers [16] make them a tricky target to pursue, and a major hurdle in the successful management of this malignant disease.

1.2. Systemic Delivery Challenges

Most of the conventional treatments for the management of cancers involve chemotherapy using low molecular weight anticancer agents that are systemically administered by the intravenous (i.v.) route. This intervention inherently lacks the ability to target tumors selectively. The drug indiscriminately diffuses across blood vessels into normal tissues and tumors alike, not only causing acute and often dose limiting side effects to cancer patients [17, 18] but also effecting in dilution of the drug, wherein the percent-injected dose that usually reaches the tumor is often very low, leading to suboptimal drug utilization and efficacy [19]. Low molecular weight anticancer compounds also suffer from short plasma circulation half-lives due to their rapid clearance through renal excretion. Also naked proteins, peptides, DNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and therapeutic molecules that are administered via the blood stream are generally labile and prone to degradation in the presence of serum or plasma components [20, 21]. These shortfalls make systemic delivery of drugs and genes a great challenge.

1.3. Role of Molecular Imaging in Cancer

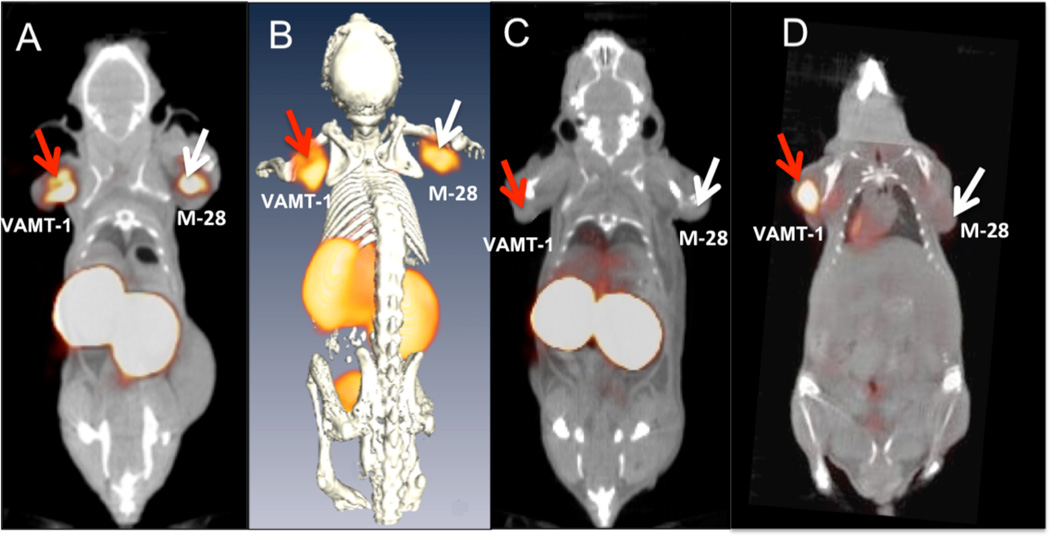

Many cancers can be prevented, better managed, or even cured if the pathological tissue is detected early and the progression of the disease can be effectively monitored through physiological rather than anatomical changes [22, 23]. In this regard, molecular imaging using targeted contrast agents, such as nuclear and optical probes, can play a leading role in screening, detection, and management of cancers [24, 25]. Imaging the molecular features or signatures of cancer cells/tissues can also serve an important clinical function [26–28]. For instance, molecular imaging using radiolabeled ligands, antibodies, or peptides that can target/bind to molecular markers, receptors or over-expressed targets on specific tumor cell surfaces can not only help locate such tumors (Fig. 1) [29], but also be used to study the biological effects of such molecules in the progression of the disease [30]. Also, imaging the downstream markers or effector molecules that signal cell death or apoptosis can provide indicators of treatment response much earlier than physical changes start to appear, such as tumor shrinkage [31]. Thus, molecular imaging of cancers can afford a gamut of meaningful information that can be applied for mechanistic understanding of the disease [32] as wells as early detection [33], and for studying multiple events, such as non-invasive visualization of accumulation/localization of the nanoparticles in vivo, its biological fate, visualizing the progression/regression of the disease [25], and quantifying the effect of drug treatment in individual patients that usually vary on a case-by-case basis. Molecular imaging technology as applied to a cancer therapy is thus heralded to play a major role in the era of personalized medicine [34].

Fig. (1).

Novel radiolabeled scFv antibodies for targeted imaging of tumors. The figure shows in vivo tumor targeting and imaging of 99mTc-labeled M40 single chain fragment antibody (scFv) in mouse bearing both sarcomatoid (VAMT-1) and epithelioid (M28) mesothelioma. (A) Single photon emission computed tomography/X-ray computed tomography (SPECT/CT) fused coronal image of 99mTc-M40 imaged 3 hours after injection. (B) 3D fused SPECT/CT coronal image. (C) blocking control study (the target-mediated uptake is confirmed by ≈ 70 % reduction in tumor activity following administration of 10-fold excess of unlabeled scFv). (D) Positron emission tomography/X-ray computed tomography (PET/CT) fused coronal image of 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) imaged 1 hour after injection (for comparison). The figure shows the ability of the novel M40 scFv to target both sarcomatoid (VAMT-1) and epithelioid (M-28) mesothelioma tumors effectively in mouse models demonstrating the utility of such agents in imaging/detection of all subtypes of mesotheliomas. Adapted with permission from Ref. [29]. Copyright AACR (2011).

2. MOLECULAR IMAGING SYSTEMS IN CANCER

As discussed in the above section, the role of imaging in characterization of cancers at the molecular level would have major clinical implications, especially, for early detection of the disease, predicting the risk of tumor formation from precancerous lesions and ways to manage and treat the disease, including development of new molecular target based therapeutics [35]. In this regard, imaging systems has already been an integral part in screening, diagnosis, and staging of many cancers [28]. Among them, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been a popular tool in tumor detection because of its high depth penetration, spatial resolution and high soft tissue contrast [36]. More importantly, MRI-based imaging circumvents the use of harmful ionizing radiation [37]. A significant amount of research in the field of MRI has been focused on the development of contrast agents to improve image signal intensity, and among them Gd3+-based MRI agents have been most successful [38, 39].

X-ray computed tomography (CT) has also been used extensively for screening, detection, and measuring the progression of cancer in clinics [40]. In the conventional setting iodinated contrast agents are generally used to enhance the contrast for CT imaging. One such example is the intraarterial (i.a.) administration of the first commercially available polymer conjugated anticancer agent, SMANCS that is given to patients using iodinated lipid contrast agent (Lipiodol®). SMANCS-Lipiodol® serves both as a diagnostic tool and a drug for therapeutic use; the contrast agent helps detect the accumulation of SMANCS in solid tumors and also facilitates imaging/monitoring the regression of tumors based on X-ray CT [41]. It has been reported that the radiation exposure to patients while undergoing CT scans in the past may itself serve as a source of cancers [42], however with the advancement in novel imaging technologies such as low-dose CT, the mortality from cancers could not only be reduced but the screening also resulted in detection of many tumors at early stages [43].

Among the nuclear modality imaging, positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) having high detection sensitivity has been the most sought, for staging and follow up of solid tumors in patients in the clinics [44, 45]. Also, the vast choice of radionuclides and versatility of conjugation chemistries available for radiolabeling are yet another key advantage with nuclear modality imaging [46, 47]. Another prominent feature of nuclear imaging is its ability to image biological processes and metabolic activity in tissues and organs, e.g., PET using the analog of glucose 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) containing the 18F isotope with a moderate half-life ≈ 110 min and high-energy positron emission (0.6335 MeV) [48], is routinely used to detect tumors [49]. Solid tumors usually have higher uptake of 18F-FDG due to relative higher levels of glucose transporters and the action the enzyme hexokinase [50]. The average FDG PET sensitivity and specificity across all oncology applications is estimated at 84 % [51]. However, the production of positron emitting PET nuclides generally requires a dedicated and costly cyclotron in close proximity to the imaging facility due to the short half-lives of radionuclides. It is for this reason that radiolabeling drugs/molecular markers with PET-radiotracers are difficult to produce and image within the time frame of their decay [52]. 68Ga is a valuable alternative to 18F for PET imaging because it does not need an on-site cyclotron and also because of its high positron emission of 1.899 MeV [52, 53].

Another alternative to PET, is the use of SPECT imaging. Although SPECT generally has lower radionuclide detection efficiency over PET, recent advancements in multi-aperture pinhole SPECT technology significantly reduces the difference in detection efficiencies between both modalities [54]. 99mTc is a versatile radioisotope for SPECT imaging that emits readily detectable 140 KeV γ-rays with a half-life ≈ 6 h [55]. The time frame of its decay is ideally suited for labeling for in vivo setting because it is long enough for scanning with SPECT instrument but at the same time keeps the radiation exposure low and helps reduce radiation burden to patients [55]. 99mTc is thus currently the most commonly used isotope for disease diagnosis, especially for cancers. Gamma emitting SPECT nuclides such as 111In, having longer half-lives, could be advantageous in imaging pharmacokinetics and tissue biodistribution of radiolabeled drugs in small animal models, using micro-SPECT [56–58].

In the past few decades, along with the increased interest in novel nanoprobe development, there has been a burgeoning growth in the development of cross-functional imaging technologies that are revolutionalizing the field of biomedical imaging and nanotechnology. For instance, CT or MRI that can provide structural information are being combined with radionuclide imaging techniques such as PET/SPECT or optical imaging that lacks these features [59]. Some such examples include the clinical hybrid/fused PET-CT and SPECT-CT [60], and preclinical small animal micro-PET/SPECT-CT imaging systems, which has the ability to co-register both functional and anatomical features previously lacking in SPECT or PET alone [61]. In this regard, it is important to note that the breakthrough in preclinical small animal imaging systems have helped to carry forward the advances made in translational research into clinical practice [61, 62]. Other combinations of functional and structural imaging modalities such as PET/MRI and optical/MRI are also under development for both preclinical and clinical imaging [63].

Among the non-radioactive imaging tools, optical imaging using fluorescently labeled drugs/molecular markers is becoming very attractive and promising for in vitro screening as well for in vivo preclinical/clinical assessments [64–66]. Nevertheless, the application of fluorescence imaging for detecting cancers was demonstrated as early as 1948 by Moore et al. using sodium fluorescein as the fluorophore [67]. In recent times, the two most commonly utilized optical imaging techniques are based on 2D-fluorescence reflectance imaging (FRI) and 3D-fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) imaging. The 3D tomographic imaging using FMT is in a way similar to CT scans but without the use of ionizing radiations [68].

In the current scenario of molecular marker-based cancer screening/identification and detection, fluorescence imaging is proving to be an indispensable tool for rapid assessment. Furthermore, the commercial availability of wide range of near-infrared (NIR) optical probes, the relative ease of photo-labeling and development of reliable chemical conjugation chemistries, coupled with low cost and relative easy access to optical imaging stations makes them a preferred choice for molecular imaging [65]. However, fluorescence imaging also have their own problems and pitfalls such as low sensitivity due to low penetration of fluorescent light in tissues, rapid bleaching or quenching of the fluorophore, and auto fluorescence (or false positive background signal) from soft tissues. Irrespective of these limitations, optical imaging based (nano)-probe development is moving in the right direction with many product pipelines in preclinical development [69].

3. MULTIFUNCTIONAL NANOPARTICLE DELIVERY SYSTEMS FOR CANCER

3.1. Polymeric and Liposomal Nanoparticulate Formulations

Drugs/genes encapsulated in nanoparticles offers several advantages over conventional treatment regimens in the management of cancers [70, 71]. As discussed earlier, chemotherapy involving systemic administration of a free drug (often a low molecular weight anticancer compound), suffers from many drawbacks, such as short plasma half-lives (necessitating high dose and frequent drug administration) and severe systemic toxicity due to distribution in non-target sites. Apart from these limitations, most of the anticancer drugs are hydrophobic in nature and, therefore, insoluble or poorly soluble in water, which makes it challenging to administer an adequate therapeutic dose. Encapsulation of such molecules in nanoparticulate formulations using biodegradable and biocompatible polymers or liposomal delivery systems can increase the drug payload, protect the encapsulated drugs from degradation in the bloodstream and also prolong their half-lives several folds [72–74]. Thus nanoparticulate drug formulations necessitate less frequent dose administration to cancer patients, thereby greatly improving the patient’s quality of life.

Additionally, in the conventional therapeutic approach, the only way to achieve desired clinical outcome is by waiting for tumor regression after treatment. It is impossible to know if the drug has actually reached the tumor mass or remains available for sufficient duration to induce the tumoricidal effect. In this regard, image-guided therapeutic delivery using nanoparticles offers great potential in determination of drug availability at the target site as well as monitoring the therapeutic effect of the encapsulated payload in real-time with specific information on individual patients rather relying on the averages for clinical decision making [75].

3.2. Passive and Active Targeting to Cancers

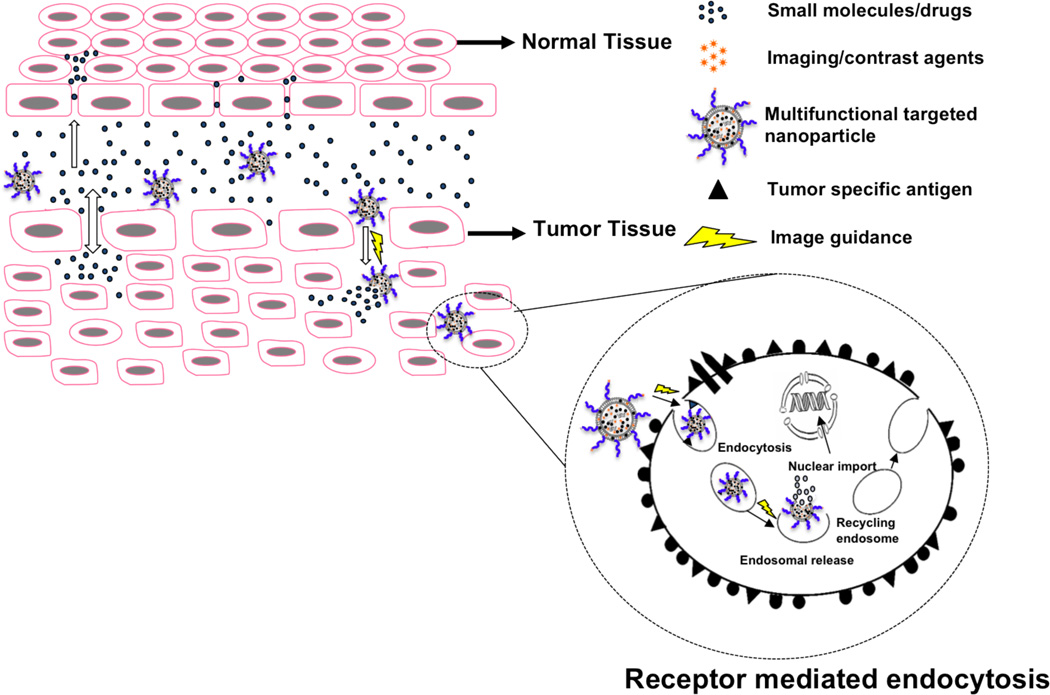

It is well known that tumor cells posses devastating invasive potentials and divide and multiply at phenomenal rates. In order to cater to the ever-increasing oxygen and nutritional demands of the growing tumors, cancer cells start “neovasculatization” or the formation of new blood vessels. This phenomenon of “angiogenesis” then starts to feed the rapidly growing tumor mass [76]. The tumor microenvironment and angiogenic characteristics of solid tumors are thus found to be very different from normal tissues. For instance, the tumor blood vessels are often aberrant or “leaky” [77]. The endothelial cells are disorganized or poorly aligned with large fenestrations and the perivascular cells and basement membrane are frequently abnormal or totally absent in the vascular wall. Furthermore, tumor tissues have a wide lumen and often lack the lymphatic clearance system [78–80]. It was found that the anatomical defectiveness and the functional abnormalities of the tumor blood vessels could be used to deliver macromolecular anticancer drugs selectively to solid tumor tissues - a phenomenon called the “enhanced permeability and retention” (EPR) effect of macromolecular drugs (Fig. 2), discovered by Matsumura and Maeda more than two and a half decades ago [80].

Fig. (2).

Passive and active tumor drug targeting. The scheme shows the passive and active targeting mechanisms of multifunctional image guided nanoparticles and the difference in the vasculature of normal and tumor tissues. Drugs and small molecules diffuse freely in and out of the normal and tumor blood vessels due to their small size and thus the effective drug concentration in the tumor drops rapidly with time. On the opposite, macromolecular drugs and nanoparticles can passively target tumors due to the leaky vasculature, but they cannot diffuse back into blood stream due to their large size (EPR effect). Targeting molecules such as antibodies or peptides present on the nanoparticles can selectively bind to cell surface receptors/antigens overexpressed by tumor cells and can be taken up by receptor-mediated endocytosys (active targeting). The image guiding molecules and contrast agents conjugated/encapsulated in the nanoparticles can be useful for targeted imaging and (non-invasive) visualization of nanoparticle accumulation/localization, as well as for mechanistic understanding of events and efficacy of drug treatment simultaneously.

Most solid tumors have elevated levels of vascular permeability mediators such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), prostaglandins (PGs), bradykinin (BK), nitric oxide (NO), and peroxynitrite [81–84]. The overproduction of the vascular permeability mediators and the defective vascular architecture leads to extensive leakage of blood plasma components, lipid particles, and macromolecules into the tumors interstitium [85]. Furthermore, the slow venous return in the tumor tissues and the poor lymphatic drainage system helps retain the macromolecules for extended times periods while the extravasations into the tumor tissues continues [86]. It is thus possible to achieve very high local concentration of the macromolecular drugs in the tumor tissues. Drugs and genes encapsulated in macromolecular delivery systems such as liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and micelles are thus able to take advantage of this unique phenomenon to passively target tumor tissues [87, 88]. The EPR effect is now considered as a guiding principle for passive tumor targeting using polymer drug conjugates and nanoparticles [86, 89].

In general, macromolecules above the renal excretion threshold (typically above 40 kDa) are able to circulate for long periods of time in the blood and accumulate in solid tumors [87]. Also, liposomes, polymeric micelles and nanoparticles in the size range of 20–200 nm have been shown to extravasate and accumulate effectively in the tumor tissues [90]. This is because the vascular pore size in the solid tumors can range from 200 to 600 nm [91]. The EPR effect will be optimal if the nanosystems can evade the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and show prolonged circulation half-life in the blood. In this regard, grafting a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) chain to the nanosystems can provide stealth characteristics and allow RES escape thereby rendering long plasma circulation half-life. For example, in the clinical setting doxorubicin loaded in PEG-grafted liposomes demonstrated enhanced tumor accumulation of doxorubicin and reduced toxicities compared with the free form of the drug [92].

Passive targeting can be a gateway to deliver drugs and imaging agents to many of the vascularized solid tumors, however, the delivery to avascular, hypovasclar, or necrotic regions of tumors still remains a challenge [93]. In this regard, active targeting using antibodies/ligands that can recognize and selectively bind to antigens or receptors overexpressed on tumor cells can be more promising (Fig. 2). Also, the specificity and delivery efficiency of passively targeted nanosystems can be remarkably improved when tumor targeting ligands are also made part of the delivery systems [94]. One such nanoparticulate delivery system developed in our group is based on epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) peptide-grafted nanoparticles for active targeting to MDR ovarian cancer cells overexpressing EGFR [95, 96]. Werner et al. have used folate-based active targeting to deliver nanoparticles to ovarian cancer that overexpress folate receptors[97]. Such particles are internalized by active transport via receptor-mediated endocytosis [98]. In another example of active targeting, the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) tripeptide was coupled to nanoparticles to target α5β5 or α5β3 integrin receptors that are overexpressed on vascular endothelial cells of angiogenic blood vessels of the proliferating tumor cells [99]. Nucleic acid construct such as aptamers that can selectively bind to prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) on prostate cancer cells are also being pursued as active targeting agents to target prostate tumors[100].

In effect, active targeting using ligands or antigens coupled to nanoparticles serve as secondary targeting mechanism for binding/intracellular trafficking of the drug payload [101] after the primary (passive) targeting based on the EPR effect (Fig. 2). Such multimodal smart delivery systems are currently intensely pursued and have the potential to revolutionalize cancer theranostics [102].

3.3. Multifunctional Polymeric Nanoparticulate Delivery Systems

The aim of developing a multi-functional nanoparticulate delivery system is to achieve several inter-related goals using a single “nanoplatform”. For instance, a nanosystem can be designed with low, moderate, or high level of complexity depending on the requirements of the delivery system and the disease target in the body such as: i) protection of the payload from degradation on systemic delivery and elimination of the side effects associated with free drug [103]; ii) evasion of the immune system and reduction in RES clearance by surface functionalization of nanoparticles with stealth molecules, such as PEG, thereby enabling long circulation half-life in vivo [104]; iii) to take advantage of the nano-size and passively target tumor tissues based on the EPR effect [105]; iv) to load with single (and often large doses of) or multiple therapeutic payloads that works synergistically to have a compounded effect on tumor therapy [106, 107]. In this regard, biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles based delivery also offers the flexibility to devise the system to have spatial and temporal control (or controlled erosion characteristics) [108–110]. For example, the delivery vehicle can be engineered to release one agent concomitantly with another or if desired, after a time delay, or in a controlled fashion based on the therapeutic requirement of the payloads [108]; v) surface decoration with targeting molecules such as antibodies or peptides that can help locate, bind, and/or internalize the nanoparticles into the tumor cells, or with agents that can trigger the release of the payload (drugs/genes) in specific location or organelles within the tumor cells [89, 111–114]; and, vi) targeted and non-targeted nanoparticles can be designed to facilitate intracellular distribution of the payload that can be critical for many drugs and genes whose sites of action are generally located in the cytoplasm or the nucleus [115]. For example, plasmid DNA, oligonucleotides, micro RNA, siRNA, peptides, and proteins have their targets in the cytoplasm or nucleus. Thus, there is a need for these molecules to be transported inside the cell [115]. More importantly, intracellular trafficking of drugs and genes is more challenging for morbid and recalcitrant tumor cells equipped with drug efflux pumps such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and MDR proteins, which are responsible for MDR [116]. In such cases, nanoparticle-based delivery systems have shown to evade the drug efflux pathway, thus increasing the intracellular drug delivery efficiency [117, 118].

4. IMAGE-GUIDED DELIVERY SYSTEMS FOR CANCERS

4.1. Rationale for Image-Guided Delivery

The concept of image guidance as an integral component of drug delivery system has major advantages over conventional methodologies of drug treatment. For instance, in the conventional scenario an anticancer drug or a therapeutic agent is systemically administered to cancer patients. This type of delivery often lacks targeting of drugs/genes to specific organs/tissues or sites of interest (tumors), and there is neither any means of (in situ) tracking or imaging the in vivo fate nor the ability to measure the delivery efficiency of drugs/genes. Also, the bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and dose response of drug/gene treatment has to be estimated based on separate sets of experiments. For example, imaging the regression of tumors in patients after drug treatment by imaging modalities such as X-ray CT or radiographic examination will in itself be a separate intervention. In this regard, co-administering the image guiding molecules as part of the delivery system can help to achieve multiple goals in a single dosing, such as real-time and concurrent assessment of drug delivery efficiency/targeting, in vivo fate of drug and sites of localization/accumulation, modes of excretion, as well as imaging and monitoring the progress of drug treatment.

4.2. Role of Imaging in Nanotechnology

As discussed above, molecular imaging using conventional molecules such as contrast agents and optical/radiolabeled probes based on molecular markers have played a key role in disease identification, monitoring, and staging of cancers. Nanotechnology is another important area of science that is growing rapidly, which involves development of novel materials at the nanometer length dimensions, with unique physico-chemical properties that neither resemble the bulk nor the native molecular forms of the individual components [119]. Apart from catering to the broad interest in the area of biomedical research, nanotechnology is poised to play a leading role in biomedical imaging especially for medical conditions such as cancer [120]. In this regard, the merging of nanotechnology with molecular imaging provides a versatile platform for novel (nano-) probe design that can augment the capabilities of conventional imaging agents such as enhanced sensitivity, specificity and signal amplification and also provide a modular platform for devising systems with multifunctional features. For instance, nanoparticles can be designed with fluorescent dyes, radioactive probes, contrast agents, and therapeutic molecules (anticancer drugs and oligonucleotides), all in a single construct that can facilitate multimodal and multipronged strategies for simultaneous detection, prognosis, and treatment of cancers. [59, 107, 121–124].

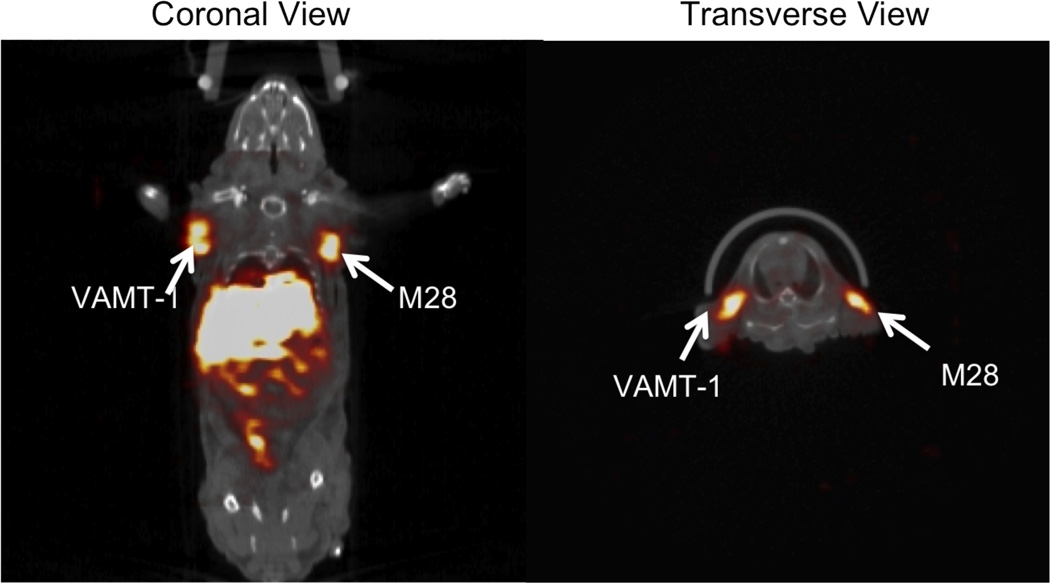

Many of the biocompatible polymers are suited to encapsulate drugs and therapeutic molecules in high concentrations/loading [125]. Furthermore, many polymeric systems have versatile (and often abundant) functional groups that can: i) facilitate synthesis of novel block copolymers that can assist in self assembly [125, 126]; or, ii) be used for conjugation of multiple types of imaging probes/drugs [127]; as well as, iii) targeting ligands for multimodal (targeted-) imaging [128]. Such multifunctional polymeric systems can form stable self-assembled nanostructures capable of drug/gene encapsulation, with built-in image guidance [129]. Nanoparticles are also of great value in evaluating the stability and in vivo fate of the delivery systems itself for developing robust nanosystems for future clinical applications. Examples of these nanosystems include dendrimers, liposomes (Fig. 3), polymeric micelles and nanoparticles [117, 130–137].

Fig. (3).

Radiolabeled immunoliposomes for targeted imaging of tumors. SPECT/CT fused images (coronal view, and transverse view) of 111In- labeled targeted immunoliposomes taken after 24 h after injection in mouse bearing both sarcomatoid (VAMT-1) and epithelioid (M28) mesothelioma. The uptake of the radiolabeled immunoliposome in both epithelioid (M28) and sarcomatoid (VAMT-1) subtypes of mesothelioma tumors at 24 h is clearly seen. Adapted with permission from Ref. [101]. Copyright Elsevier (2011).

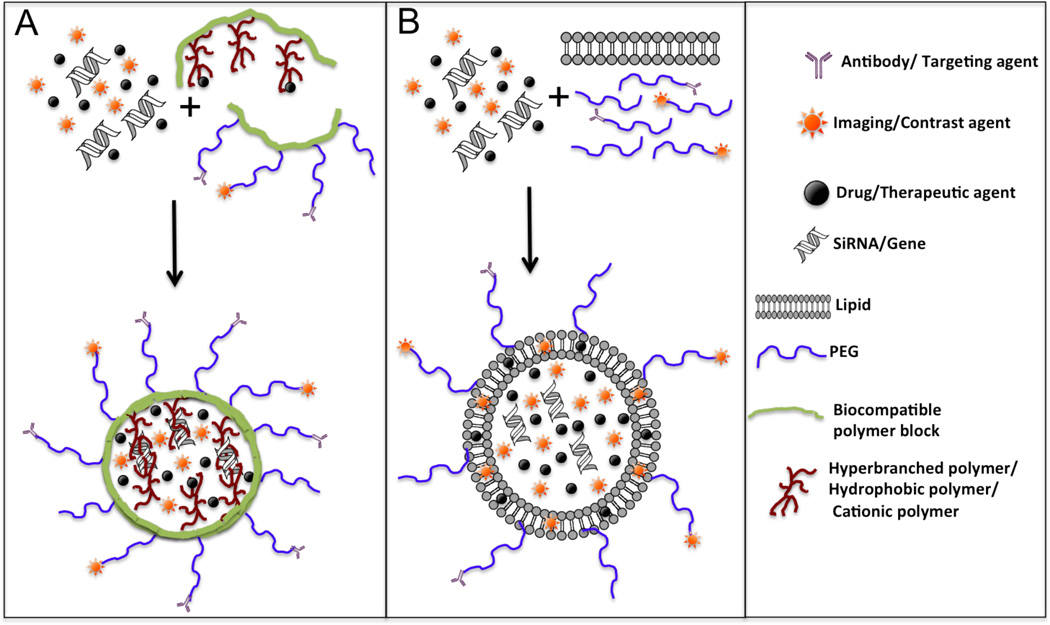

For the development of such diverse multifunctional image-guided delivery systems, traditional “one polymer-at-a-time” approaches are laborious and time consuming and require large amount of resources for optimization and arriving at the right formulation for the intended therapeutic application. In this respect, combinatorial approaches and high throughput polymer synthesis and screening are needed [138–140]. Also, high-throughput methods can be used for better understanding of structure-property relationship between the components forming the nanosystems such as carrier polymer and the drug/genes encapsulated within them. In our laboratory, we are developing a novel “mix and match” type combinatorial polymer library screening [139] and depending on the type of biodegradable/biocompatible carrier polymers, their molecular weight, surface charge, functionality, and hydrophilic/hydrophobic character they can be matched with the drug or gene of interest [139]. In this regard, targeting the polymeric nanosystems with ligands (biomarkers, antibodies, peptides), and imaging (MRI, optical, radioactive) probes can provide a quick and reliable assessment on the right ratios of the building blocks for efficient and stable encapsulation of drugs and genes into the nanoparticles [71]. This type of approach will, therefore, expedite the rational design and development of multifunctional nanosystems in cancer therapy. Another important criterion in selection of materials is the inherent toxicity/non-compatibility of some of the components used in building the multi-component delivery systems. The combinatorial “mix and match” type screening can thus be useful in developing and identifying nanosystems that can be designed, for instance to be biocompatible or devoid of immunogenicity/toxicity or complement activation in vivo, by the right choice/selection of materials such as incorporation of counter ion containing moieties to reduce surface charge or by including PEG-modified blocks to prevent immune recognition [141]. The schematic representation of formation or self-assembly of multifunctional nanoparticles from the corresponding building blocks is shown in Fig. (4).

Fig. (4).

Multifunctional nanosytems for theranostics. Schematic representation of the formation of: (A) multifunctional self-assembled targeted nanoparticle, and (B) multifunctional targeted radio-immunoliposome from the corresponding building blocks. The multifunctional nanoparticles and liposomes can be engineered by self-assembly of polymers/lipids containing various functionalities such as amphiphilic block copolymers, to facilitate formation of stable nanoparticles loaded with drugs, genes, and imaging agents; antibody and radiolabeled polymer blocks for targeting and imaging; as well as, PEG chains for enabling long circulation half-life in vivo.

5. ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLES OF IMAGE-GUIDED DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS FOR CANCER

The approach of using imaging and contrast agents for monitoring drug delivery has already been a part of clinical intervention. For example the first prototype polymer conjugated drug SMANCS dissolved in a iodinated lipid contrast medium (Lipiodol®) is used clinically for simultaneous drug delivery, tumor detection, and measuring the delivery efficiency in patients using X-ray CT [142].

Recently, more sophisticated and complex designs for image guided drug delivery are being assessed in the in vitro and preclinical settings by utilizing nanotechnology. Along these lines, Yu et al, have developed PSMA aptamer-conjugated to superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin that could be used for prostate cancer-specific nanotheranostics [143]. These agents are capable of not only detecting prostate tumors in vivo (by MRI) but also can selectively deliver doxorubicin to the tumor tissues [143].

In another study, Santra et al. have used multimodal optical and MRI agents containing biocompatible nanoparticles that could demonstrate targeted optical/MR imaging and cell killing towards folate receptors expressing cancer cells [144]. A modified solvent diffusion method was also developed for co-encapsulation of both an anticancer drug (docetaxel) and NIR dyes into nanoparticles, which are new additions to the arsenal of nano-delivery systems for detection, diagnosis, and treatment of cancers [144].

Ross’s group has been actively pursuing light-activable theranostic nanoparticles for the imaging and photodynamic therapy of brain tumors [145]. In this construct, both iron oxide nanoparticles and photofrin (a potent photosensitizer) was incorporated within PEG-modified polyacrylamide nanoparticles [145]. Further, the particles were tagged with a vascular homing (F3) peptide that binds selectively to nucleolin on angiogenic endothelial cells and tumor cell surfaces. These particles demonstrated selective targeting and pronounced antitumor effect in rat brain animal tumor models [145].

In another approach, quantum dot (QD)-aptamer conjugates were used for concurrent cancer imaging and therapy of doxorubicin delivery based on the bi-fluorescence resonance energy transfer (Bi-FRET) technique [146]. The surface of quantum dots was functionalized with a RNA aptamer that could recognize the extracellular domains of PSMA. The anticancer drug, doxorubicin was intelligently loaded onto the nanosystem by intercalation of drug in the double-stranded stem of aptamer forming the QD-aptamer (doxorubicin) conjugate with reversible self-quenching properties based on a Bi-FRET mechanism [146]. This smart multifunctional nanoparticulate system was able to deliver doxorubicin to the targeted prostate cancer cells as well as sense and image the drug delivery to the cancer cells by activating the fluorescence of QDs [146]. Such advanced delivery systems demonstrate the versatility of nanoparticles for highly specific, sensitive and therapeutically effective strategies for simultaneous disease detection and therapy.

Koo et al. have used pH responsive polymeric micelles for simultaneous non-invasive in vivo imaging and photodynamic therapy of tumors in mice models [147]. A Michael type addition reaction was utilized to conjugate a pH-sensitive polymer, poly(b-amino ester) with methoxiPEG. The block copolymer could self assemble with hydrophobic radiosensitizer protoporphyrin IX (PpIX), forming stable nanosized micelles. These micelles showed marked pH-responsive demicellization and release of the photosensitizer in the tumors due to the acidic pH conditions. Furthermore, the micelles showed clear tumor accumulation as assessed by fluorescence imaging and complete tumor ablation when irradiated with laser light in tumor bearing mice models, thereby demonstrating their potentials for photodynamic theranostics [147].

6. ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLES OF IMAGE-GUIDED NUCLEIC ACID DELIVERY FOR CANCER

Gene therapy based on RNA interference (RNAi) mechanism has been well established and has currently become a major area of research that hold great promise for the management of diseases such as cancers. Although RNAi agents have high efficiency and specificity, the major hurdle still remains its delivery to target tumor/tissues and intracellular trafficking after localization in the sites of interest [148]. In this regard, the ability to image/detect and deliver siRNA has become increasingly important. Researchers in Moore’s group have developed a dual-purpose probe for in vivo delivery and simultaneous imaging of siRNA accumulation in tumors by using high-resolution MRI and NIR in vivo optical imaging techniques [149]. The siRNA was covalently conjugated to nanoparticles consisting of NIR dye conjugated magnetic nanoparticles. Furthermore, the nanoparticles were decorated with a specific membrane translocation peptide that enables their intracellular delivery and cytosolic availability [149]. Taken together, their study demonstrates the feasibility of in vivo tracking of siRNA, in vivo dual modality imaging of tumor uptake of nanoparticles, as well as silencing ability of the siRNA-conjugated nanoparticles [149].

In another study, Kumar et al. used superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as a construct for combined optical/MR imaging and delivery of siRNA to solid tumors [150]. The nanoconstruct, apart from performing its function as a dual modality imaging agent and a vehicle for the delivery of siRNA also served as a tool to study basic tumor biology and therapy [150]. The nanoconstruct consisted of magnetic nanoparticles (for MRI), a Cy3 fluorophore (for optical imaging), a targeting peptide (EPPT) that could home to a specific antigen (uMUC-1) overexpressed by the majority of human breast cancer cells, and a synthetic siRNA that downregulates the BIRC5 antiapoptotic gene in breast cancer cells [150]. The nanoconstruct demonstrated specific tumor uptake and significant downregulation of BIRC5 gene, in animal tumor models. More importantly, the tumor uptake could be visualized both by MRI and NIR optical imaging [150].

Researchers from Park’s group developed a polyelectrolyte complex micelle-based VEGF siRNA delivery system for anti-angiogenic gene therapy [141]. The complexation of the PEG-conjugated VEGF siRNA was achieved by charge interaction with poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI). This complex formed a stable core-shell nanostructure with the PEI/siRNA forming the central core and PEG chains forming the corona. The i.v. and i.t. injection of the micelles in mice demonstrated significant inhibition of VEGF expression in the tumor tissue and suppressed tumor growth without detectable toxicities [141]. Furthermore, to confirm the feasibility of siRNA-based gene therapy and imaging in vivo, optical imaging was undertaken using a Cy5.5 labeled siRNA. The Cy5.5 labeled siRNA containing polyelectrolyte complex micelles predominantly accumulated in the tumor, affirming the feasibility of this approach [141].

In order to overcome the dose-limiting side effects of conventional chemotherapeutic agents and the therapeutic failure due to MDR, we designed and evaluated a novel biocompatible lipid-modified dextran-based self-assembled polymeric nanosystem that could encapsulate MDR-1 siRNA as well as doxorubicin [71, 151]. Further, in order to image the transfection efficacy of siRNA-loaded nanoparticles on cell lines we utilized the green fluorescence protein (GFP) expressing BHK-21 cells, and performed confocal fluorescence microscopy to visualize the downregulation of GFP. It was observed the GFP siRNA was efficiently incorporated into cells and effectively inhibited the expression of GFP in a dose dependent manner. Similarly, the MDR1 siRNA-loaded dextran nanoparticles efficiently suppress P-gp expression in a drug resistant osteosarcoma cell lines. A combination therapy of the MDR1 siRNA-loaded nanocarriers with doxorubicin revealed pronounced increase in drug uptake in the nucleus (assessed by confocal fluorescence microscopy imaging) of MDR cells. These results demonstrate that our approach may be useful in reversing MDR by increasing the amount of drug accumulation in MDR cells. Thus, the delivery using non-toxic and biocompatible dextran-based nanosystems offers a versatile platform for the incorporation of multiple payloads for simultaneous imaging and delivery of therapeutic molecules that can be translatable for human clinical applications.

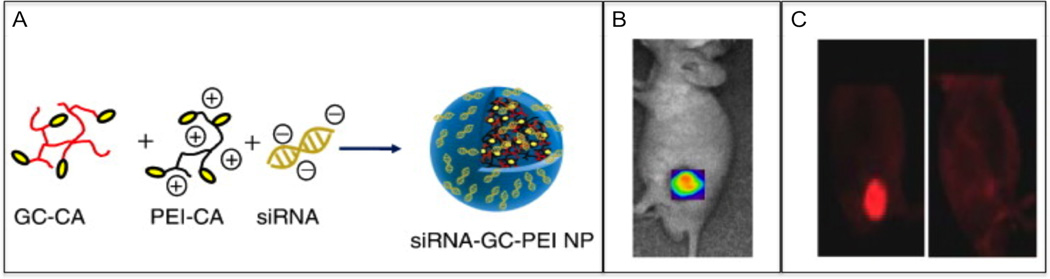

In another study, Huh et al. designed a siRNA delivery system containing the biodegradable and biocompatible polymer glycol chitosan (GC) and PEI (Fig. 5) [152]. The polymers were conjugated with 5β-cholanic acid (CA) to stabilize the nanoparticles and endow them with tumor-homing ability. The nanoparticles were formed by mixing GC-CA and PEI-CA to form self-assembled GC–PEI nanostructures, due to the strong hydrophobic interactions of 5β-cholanic acids in the polymers. The cationic charge on the GC–PEI nanoparticles was used to complex with the negatively charged red fluorescence protein (RFP) gene silencing siRNA designed to inhibit RFP expression. In vitro studies with RFP expressing B16F10 tumor cells incubated with siRNA–GC–PEI nanoparticles revealed time-dependent cellular uptake of the nanoparticles, and lead to a significant inhibition of RFP gene expression in RFP/B16F10-bearing mice models, thus demonstrating their potentials as a promising vector for siRNA delivery (Fig. 5) [152].

Fig. (5).

Image-guided gene silencing using polymeric nanoparticles. (A) Schematic representation of siRNA-loaded in hydrophobically-modified GC and PEI nanoparticle (siRNA-GC-PEI NP). (B) In vivo NIR fluorescence imaging of SCC7 tumor-bearing mice 1 h post-injection of Cy5.5-siRNA-GC-PEI NP. (C) In vivo knockdown of targeted proteins by siRNA (left image) and siRNA-GC-PEI NP (right image) after i.v. injection in B16F10-RFP tumor-bearing mice. The mice were observed by dual modality imaging using light microscopy and by NIR fluorescence imaging system. Adapted with permission from Ref. [152]. Copyright Elsevier (2010).

CONCLUSIONS

Multifunctional nanoparticles utilizing the active and passive tumor targeting principles has played a leading role in addressing some of the critical issues related to cancer drug delivery, such as overcoming the inherent limitations of drug/genes (with regard to stability, non-specificity, and short half-life), and the anatomical and patho-physiological barriers in delivering them specifically to tumor tissues. In this respect, the role of image guidance is of paramount importance in drug delivery and many of the nanosystems currently employ image guiding molecules or drugs/genes labeled with imaging probes for several reasons, i.e., measuring delivery efficiency, selectivity, sites of localization of drugs/genes, and concurrent measurement of the drug treatment response (such as reduction in tumor volume). Also, in situ imaging of the molecular events while the drug is being delivered using nanoparticles can provide startling insights about the molecular mechanism of tumor progression (such as its invasion and metastatic behavior) that can assist a great deal in the future design and development of novel molecular nanoprobes-based delivery systems. More importantly, the development of such image-guided delivery systems can aid in the early detection of cancers, which can be regarded as one of the most powerful tools in deciphering possible cures for this deadly disease. These types of advanced multifunctional precision image-guided nanosystems are thus envisaged to play a major role in the era of personalized cancer therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to acknowledge the support from the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Nanotechnology Platform Partnership (CNPP) grant U01- CA151452 to Mansoor Amiji, and NIH R01 CA135358 and the American Cancer Society grant IRG-97-150-10 to Jiang He.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Bi-FRET

bi-fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- BK

bradykinin

- CA

5β-cholanic acid

- CT

X-ray computed tomography

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptors

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- 18F-FDG

2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose

- FMT

3D-fluorescence molecular tomography

- FRI

2D-fluorescence reflectance imaging

- GC

glycol chitosan

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- i.a.

intraarterial

- i.t.

intratumoral

- i.v.

intravenous

- MDR

multi-drug resistance

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIR

near-infrared

- NO

nitric oxide

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEI

poly(ethyleneimine)

- PET

positron emission tomography

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- PGs

prostaglandins

- PpIX

protoporphyrin IX

- PSMA

prostate-specific membrane antigen

- QD

quantum dot

- RES

reticuloendothelial system

- RFP

red fluorescence protein

- RGD

arginine-glycine-aspartic acid

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta PB, Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. Cancer stem cells: mirage or reality? Nat. Med. 2009;15(9):1010–1012. doi: 10.1038/nm0909-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hajj M, Clarke MF. Self-renewal and solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(43):7274–7282. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Zaguilan R, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Chu YW, Gillies RJ, Hendrix MJ. Acidic pH enhances the invasive behavior of human melanoma cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1996;14(2):176–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00121214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatenby RA, Gawlinski ET. The glycolytic phenotype in carcinogenesis and tumor invasion: insights through mathematical models. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):3847–3854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asosingh K, De Raeve H, de Ridder M, Storme GA, Willems A, Van Riet I, Van Camp B, Vanderkerken K. Role of the hypoxic bone marrow microenvironment in 5T2MM murine myeloma tumor progression. Haematologica. 2005;90(6):810–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang CV, Lewis BC, Dolde C, Dang G, Shim H. Oncogenes in tumor metabolism, tumorigenesis, and apoptosis. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1997;29(4):345–354. doi: 10.1023/a:1022446730452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(2):225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milane L, Duan Z, Amiji M. Role of hypoxia and glycolysis in the development of multi-drug resistance in human tumor cells and the establishment of an orthotopic multi-drug resistant tumor model in nude mice using hypoxic pre-conditioning. Cancer Cell. Int. 2011;11:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutour A, Leclers D, Monteil J, Paraf F, Charissoux JL, Rousseau R, Rigaud M. Non-invasive imaging correlates with histological and molecular characteristics of an osteosarcoma model: application for early detection and follow-up of MDR phenotype. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(6B):4171–4178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biedler JL. Genetic aspects of multidrug resistance. Cancer. 1992;70(6 Suppl.):1799–1809. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:4+<1799::aid-cncr2820701623>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabr-Milane LS, van Vlerken LE, Yadav S, Amiji MM. Multifunctional nanocarriers to overcome tumor drug resistance. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2008;34(7):592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnenberg VS, Donnenberg AD. Multiple drug resistance in cancer revisited: the cancer stem cell hypothesis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;45(8):872–877. doi: 10.1177/0091270005276905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cahill DP, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. Genetic instability and darwinian selection in tumours. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9(12):M57–M60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeb LA, Loeb KR, Anderson JP. Multiple mutations and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100(3):776–781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowinsky EK, Chaudhry V, Forastiere AA, Sartorius SE, Ettinger DS, Grochow LB, Lubejko BG, Cornblath DR, Donehower RC. Phase I and pharmacologic study of paclitaxel and cisplatin with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: neuromuscular toxicity is dose-limiting. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993;11(10):2010–2020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinherz LJ, Steinherz PG, Tan CT, Heller G, Murphy ML. Cardiac toxicity 4 to 20 years after completing anthracycline therapy. JAMA. 1991;266(12):1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303(5665):1818–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng YC, Mozumdar S, Huang L. Lipid-based systemic delivery of siRNA. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61(9):721–731. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8(2):129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wulfkuhle JD, Liotta LA, Petricoin EF. Proteomic applications for the early detection of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3(4):267–275. doi: 10.1038/nrc1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott JJ, Ullrich A, Miller AB. The importance of early symptom recognition in the context of early detection and cancer survival. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45(16):2743–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in cancer. Science. 2006;312(5777):1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1125949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17(5):545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ntziachristos V, Chance B. Probing physiology and molecular function using optical imaging: applications to breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3(1):41–46. doi: 10.1186/bcr269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolmachev V, Orlova A, Nilsson FY, Feldwisch J, Wennborg A, Abrahmsen L. Affibody molecules: potential for in vivo imaging of molecular targets for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2007;7(4):555–568. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaffer FA, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in the clinical arena. JAMA. 2005;293(7):855–862. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer AK, Lan X, Zhu X, Su Y, Feng J, Zhang X, Gao D, Seo Y, Vanbrocklin HF, Broaddus VC, Liu B, He J. Novel human single chain antibody fragments that are rapidly internalizing effectively target epithelioid and sarcomatoid mesotheliomas. Cancer Res. 2011;71(7):2428–2432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang DJ, Azhdarinia A, Wu P, Yu DF, Tansey W, Kalimi SK, Kim EE, Podoloff DA. In vivo and in vitro measurement of apoptosis in breast cancer cells using 99mTc-EC-annexin V. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2001;16(1):73–83. doi: 10.1089/108497801750096087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumer B, Gao J. Theranostic nanomedicine for cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2008;3(2):137–140. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Spying on cancer: molecular imaging in vivo with genetically encoded reporters. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weissleder R. Molecular imaging: exploring the next frontier. Radiology. 1999;212(3):609–614. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99se18609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corsten MF, Hofstra L, Narula J, Reutelingsperger CP. Counting heads in the war against cancer: defining the role of annexin A5 imaging in cancer treatment and surveillance. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1255–1260. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mankoff DA, O'Sullivan F, Barlow WE, Krohn KA. Molecular imaging research in the outcomes era: measuring outcomes for individualized cancer therapy. Acad. Radiol. 2007;14(4):398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature. 2008;452(7187):580–589. doi: 10.1038/nature06917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semelka RC, Armao DM, Elias J, Jr, Huda W. Imaging strategies to reduce the risk of radiation in CT studies, including selective substitution with MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;25(5):900–909. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aime S, Cabella C, Colombatto S, Geninatti Crich S, Gianolio E, Maggioni F. Insights into the use of paramagnetic Gd(III) complexes in MR-molecular imaging investigations. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2002;16(4):394–406. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev. 1999;99(9):2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaneko M, Eguchi K, Ohmatsu H, Kakinuma R, Naruke T, Suemasu K, Moriyama N. Peripheral lung cancer: screening and detection with low-dose spiral CT versus radiography. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798–802. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maeda H. SMANCS and polymer-conjugated macromolecular drugs: advantages in cancer chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46(1–3):169–185. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(22):2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bangerter M, Kotzerke J, Griesshammer M, Elsner K, Reske SN, Bergmann L. Positron emission tomography with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose in the staging and follow-up of lymphoma in the chest. Acta. Oncol. 1999;38(6):799–804. doi: 10.1080/028418699432969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keidar Z, Israel O, Krausz Y. SPECT/CT in tumor imaging: technical aspects and clinical applications. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2003;33(3):205–218. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2003.127310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger F, Gambhir S. Recent advances in imaging endogenous or transferred gene expression utilizing radionuclide technologies in living subjects: applications to breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3(1):28–35. doi: 10.1186/bcr267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phelps M. PET: the merging of biology and imaging into molecular imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2000;41(4):661–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan D, Gambhir S, Toyokuni T, Iyer M, Acharya N, Phelps M, Barrio J. Rapid synthesis of a 5 -fluorinated oligodeoxy-nucleotide: a model antisense probe for use in imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8(11):1317–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wahl RL, Quint LE, Greenough RL, Meyer CR, White RI, Orringer MB. Staging of mediastinal non-small cell lung cancer with FDG PET, CT, and fusion images: preliminary prospective evaluation. Radiology. 1994;191(2):371–377. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nabi HA, Zubeldia JM. Clinical applications of (18)F-FDG in oncology. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2002;30(1):3–9. quiz 10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gambhir SS, Czernin J, Schwimmer J, Silverman DH, Coleman RE, Phelps ME. A tabulated summary of the FDG PET literature. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;42(5 Suppl.):1S–93S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitterhauser M, Toegel S, Wadsak W, Lanzenberger R, Mien L, Kuntner C, Wanek T, Eidherr H, Ettlinger D, Viernstein H. Pre vivo, ex vivo and in vivo evaluations of [68Ga]-EDTMP. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34(4):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maecke H, Hofmann M, Haberkorn U. 68Ga-labeled peptides in tumor imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2005;46(1 suppl):172S–178S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Funk T, Despres P, Barber WC, Shah KS, Hasegawa BH. A multipinhole small animal SPECT system with submillimeter spatial resolution. Med. Phys. 2006;33(5):1259–1268. doi: 10.1118/1.2190332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banerjee S, Pillai A, Raghavan M, Ramamoorthy N. Evolution of Tc-99m in diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2001;31:260–277. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2001.26205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamoudeh M, Kamleh MA, Diab R, Fessi H. Radionuclides delivery systems for nuclear imaging and radiotherapy of cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008;60(12):1329–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chow TH, Lin YY, Hwang JJ, Wang HE, Tseng YL, Pang VF, Liu RS, Lin WJ, Yang CS, Ting G. Therapeutic efficacy evaluation of 111In-labeled PEGylated liposomal vinorelbine in murine colon carcinoma with multimodalities of molecular imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2009;50(12):2073–2081. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ting G, Chang CH, Wang HE. Cancer nanotargeted radiopharmaceuticals for tumor imaging and therapy. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(10):4107–4118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones EF, He J, VanBrocklin HF, Franc BL, Seo Y. Nanoprobes for medical diagnosis: current status of nanotechnology in molecular imaging. Curr. Nanosci. 2008;4(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mariani G, Bruselli L, Kuwert T, Kim EE, Flotats A, Israel O, Dondi M, Watanabe N. A review on the clinical uses of SPECT/CT. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2010;37(10):1959–1985. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chatziioannou A. Instrumentation for molecular imaging in preclinical research: Micro-PET and Micro-SPECT. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005;2:533–536. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-079DS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cherry S. Multimodality imaging: beyond PET/CT and SPECT/CT. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2009;39:348–353. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF, Newport DF, Catana C, Siegel SB, Becker M, Thielscher A, Kneilling M, Lichy MP, Eichner M, Klingel K, Reischl G, Widmaier S, Rocken M, Nutt RE, Machulla HJ, Uludag K, Cherry SR, Claussen CD, Pichler BJ. Simultaneous PET-MRI: a new approach for functional and morphological imaging. Nat. Med. 2008;14(4):459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaijzel EL, van der Pluijm G, Lowik CW. Whole-body optical imaging in animal models to assess cancer development and progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3490–3497. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choy G, Choyke P, Libutti SK. Current advances in molecular imaging: noninvasive in vivo bioluminescent and fluorescent optical imaging in cancer research. Mol. Imaging. 2003;2(4):303–312. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sokolov K, Follen M, Aaron J, Pavlova I, Malpica A, Lotan R, Richards-Kortum R. Real-time vital optical imaging of precancer using anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2003;63(9):1999–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moore RL. Treatment of an infant with paroxysmal auricular tachycardia. Pediatrics. 1948;2(3):266–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Graves EE, Weissleder R, Ntziachristos V. Fluorescence molecular imaging of small animal tumor models. Curr. Mol. Med. 2004;4(4):419–430. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hilderbrand SA, Weissleder R. Near-infrared fluorescence: application to in vivo molecular imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010;14(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Potineni A, Lynn DM, Langer R, Amiji MM. Poly(ethylene oxide)-modified poly(beta-amino ester) nanoparticles as a pH-sensitive biodegradable system for paclitaxel delivery. J. Control. Release. 2003;86(2–3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Susa M, Iyer AK, Ryu K, Choy E, Hornicek FJ, Mankin H, Milane L, Amiji MM, Duan Z. Inhibition of ABCB1 (MDR1) expression by an siRNA nanoparticulate delivery system to overcome drug resistance in osteosarcoma. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Vlerken LE, Vyas TK, Amiji MM. Poly(ethylene glycol)-modified nanocarriers for tumor-targeted and intracellular delivery. Pharm. Res. 2007;24(8):1405–1414. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harris JM, Martin NE, Modi M. Pegylation: a novel process for modifying pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(7):539–551. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tiwari SB, Amiji MM. Improved oral delivery of paclitaxel following administration in nanoemulsion formulations. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006;6(9–10):3215–3221. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim K, Kim JH, Park H, Kim YS, Park K, Nam H, Lee S, Park JH, Park RW, Kim IS, Choi K, Kim SY, Kwon IC. Tumor-homing multifunctional nanoparticles for cancer theragnosis: Simultaneous diagnosis, drug delivery, and therapeutic monitoring. J. Control. Release. 2010;146(2):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat. Med. 1995;1(1):27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghosh K, Thodeti CK, Dudley AC, Mammoto A, Klagsbrun M, Ingber DE. Tumor-derived endothelial cells exhibit aberrant Rho-mediated mechanosensing and abnormal angiogenesis in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105(32):11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800835105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Greish K, Fang J, Inutsuka T, Nagamitsu A, Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics: advantages and prospects with special emphasis on solid tumour targeting. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(13):1089–1105. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342130-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Padera TP, Kadambi A, di Tomaso E, Carreira CM, Brown EB, Boucher Y, Choi NC, Mathisen D, Wain J, Mark EJ, Munn LL, Jain RK. Lymphatic metastasis in the absence of functional intratumor lymphatics. Science. 2002;296(5574):1883–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1071420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J. Control. Release. 2000;65(1–2):271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dvorak HF, Nagy JA, Feng D, Brown LF, Dvorak AM. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor and the significance of microvascular hyperpermeability in angiogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1999;237:97–132. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59953-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219(4587):983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iyer A, Khaled G, Fang J, Maeda H. Exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention effect for tumor targeting. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11(17–18):812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maeda H, Bharate GY, Daruwalla J. Polymeric drugs for efficient tumor-targeted drug delivery based on EPR-effect. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2009;71(3):409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duncan R, Ringsdorf H, Satchi-Fainaro R. Polymer therapeutics--polymers as drugs, drug and protein conjugates and gene delivery systems: past, present and future opportunities. J. Drug Target. 2006;14(6):337–341. doi: 10.1080/10611860600833856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, Amiji M. A review of stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug and gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2008;126(3):187–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Danhier F, Feron O, Préat V. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: passive and active tumor targeting of nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2010;148(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Davis SS. Biomedical applications of nanotechnology--implications for drug targeting and gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15(6):217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuszyk BS, Corl FM, Franano FN, Bluemke DA, Hofmann LV, Fortman BJ, Fishman EK. Tumor transport physiology: implications for imaging and imaging-guided therapy. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001;177(4):747–753. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.4.1770747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Marcucci F, Lefoulon F. Active targeting with particulate drug carriers in tumor therapy: fundamentals and recent progress. Drug Discov. Today. 2004;9(5):219–228. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Milane L, Duan ZF, Amiji M. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of lonidamine/paclitaxel loaded, EGFR-targeted nanoparticles in an orthotopic animal model of multi-drug resistant breast cancer. Nanomedicine. 2011;7(4):435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Milane L, Duan Z, Amiji M. Development of EGFR-targeted polymer blend nanocarriers for combination paclitaxel/lonidamine delivery to treat multi-drug resistance in human breast and ovarian tumor cells. Mol. Pharm. 2011;8(1):185–203. doi: 10.1021/mp1002653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Werner ME, Karve S, Sukumar R, Cummings ND, Copp JA, Chen RC, Zhang T, Wang AZ. Folate-targeted nanoparticle delivery of chemo- and radiotherapeutics for the treatment of ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Biomaterials. 2011;32(33):8548–8554. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rihova B. Receptor-mediated targeted drug or toxin delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1998;29(3):273–289. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lue N, Ganta S, Hammer DX, Mujat M, Stevens AE, Harrison L, Ferguson RD, Rosen D, Amiji M, Iftimia N. Preliminary evaluation of a nanotechnology-based approach for the more effective diagnosis of colon cancers. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2010;5(9):1467–1479. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Farokhzad OC, Karp JM, Langer R. Nanoparticle-aptamer bioconjugates for cancer targeting. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006;3(3):311–324. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iyer AK, Su Y, Feng J, Lan X, Zhu X, Liu Y, Gao D, Seo Y, Vanbrocklin HF, Courtney Broaddus V, Liu B, He J. The effect of internalizing human single chain antibody fragment on liposome targeting to epithelioid and sarcomatoid mesothelioma. Biomaterials. 2011;32(10):2605–2613. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Benyettou F, Lalatonne Y, Chebbi I, Di Benedetto M, Serfaty JM, Lecouvey M, Motte L. A multimodal magnetic resonance imaging nanoplatform for cancer theranostics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13(21):10020–10027. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02034f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.O'Brien ME, Wigler N, Inbar M, Rosso R, Grischke E, Santoro A, Catane R, Kieback DG, Tomczak P, Ackland SP, Orlandi F, Mellars L, Alland L, Tendler C. Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2004;15(3):440–449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Otsuka H, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. PEGylated nanoparticles for biological and pharmaceutical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2003;55(3):403–419. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maeda H, Matsumura Y. EPR effect based drug design and clinical outlook for enhanced cancer chemotherapy. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2011;63(3):129–130. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.van Vlerken LE, Duan Z, Little SR, Seiden MV, Amiji MM. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetic analysis of Paclitaxel and ceramide administered in multifunctional polymer-blend nanoparticles in drug resistant breast cancer model. Mol. Pharm. 2008;5(4):516–526. doi: 10.1021/mp800030k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cao N, Cheng D, Zou S, Ai H, Gao J, Shuai X. The synergistic effect of hierarchical assemblies of siRNA and chemotherapeutic drugs co-delivered into hepatic cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(8):2222–2232. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bhavsar MD, Amiji MM. Gastrointestinal distribution and in vivo gene transfection studies with nanoparticles-in-microsphere oral system (NiMOS) J. Control. Release. 2007;119(3):339–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Uhrich KE, Cannizzaro SM, Langer RS, Shakesheff KM. Polymeric systems for controlled drug release. Chem. Rev. 1999;99(11):3181–3198. doi: 10.1021/cr940351u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dillen K, Vandervoort J, Van den Mooter G, Ludwig A. Evaluation of ciprofloxacin-loaded Eudragit RS100 or RL100/PLGA nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;314(1):72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ghotbi Z, Haddadi A, Hamdy S, Hung RW, Samuel J, Lavasanifar A. Active targeting of dendritic cells with mannan-decorated PLGA nanoparticles. J. Drug Target. 2011;19(4):281–292. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2010.499463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Choi CH, Alabi CA, Webster P, Davis ME. Mechanism of active targeting in solid tumors with transferrin-containing gold nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(3):1235–1240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914140107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Choi KY, Chung H, Min KH, Yoon HY, Kim K, Park JH, Kwon IC, Jeong SY. Self-assembled hyaluronic acid nanoparticles for active tumor targeting. Biomaterials. 2010;31(1):106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pecot CV, Calin GA, Coleman RL, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK. RNA interference in the clinic: challenges and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11(1):59–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Torchilin VP. Recent approaches to intracellular delivery of drugs and DNA and organelle targeting. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006;8:343–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Panyam J, Labhasetwar V. Targeting intracellular targets. Curr. Drug. Deliv. 2004;1(3):235–247. doi: 10.2174/1567201043334768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Devalapally H, Duan Z, Seiden MV, Amiji MM. Modulation of drug resistance in ovarian adenocarcinoma by enhancing intracellular ceramide using tamoxifen-loaded biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2008;14(10):3193–3203. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.van Vlerken LE, Duan Z, Seiden MV, Amiji MM. Modulation of intracellular ceramide using polymeric nanoparticles to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(10):4843–4850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Daniel MC, Astruc D. Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2004;104(1):293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sahoo SK, Labhasetwar V. Nanotech approaches to drug delivery and imaging. Drug Discov. Today. 2003;8(24):1112–1120. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02903-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McCarthy JR, Weissleder R. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for targeted imaging and therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008;60(11):1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gindy ME, Prud'homme RK. Multifunctional nanoparticles for imaging, delivery and targeting in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2009;6(8):865–878. doi: 10.1517/17425240902932908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Koning GA, Krijger GC. Targeted multifunctional lipid-based nanocarriers for image-guided drug delivery. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2007;7(4):425–440. doi: 10.2174/187152007781058613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lammers T, Subr V, Peschke P, Kuhnlein R, Hennink WE, Ulbrich K, Kiessling F, Heilmann M, Debus J, Huber PE, Storm G. Image-guided and passively tumour-targeted polymeric nanomedicines for radiochemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer. 2008;99(6):900–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Iyer AK, Greish K, Fang J, Murakami R, Maeda H. High-loading nanosized micelles of copoly(styrene-maleic acid)-zinc protoporphyrin for targeted delivery of a potent heme oxygenase inhibitor. Biomaterials. 2007;28(10):1871–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang F, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV, Rauh RD, Roovers J. Synthesis and evaluation of a star amphiphilic block copolymer from poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and poly(ethylene glycol) as a potential drug delivery carrier. Bioconjug. Chem. 2005;16(2):397–405. doi: 10.1021/bc049784m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gillies ER, Frechet JM. Dendrimers and dendritic polymers in drug delivery. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an emerging platform for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]