Abstract

Objectives

Thanks to the success of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), HIV‐infected patients can have almost a normal life expectancy. This has resulted in an aging HIV‐infected population with other chronic comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, and depression. Our hypothesis is that patients' perceptions of and attitudes towards their cART, which is perceived as crucial to their survival, differ from their beliefs about their co‐treatments, and this may have an impact on their medication adherence.

Methods

We used the French version of the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ‐f) to measure the perceptions of patients about their co‐treatments and the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire for Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (BMQ‐HAART) to measure their beliefs about their cART in a representative sample (n = 150) of patients enrolled in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS) and followed at the Infectious Disease Service at the University Hospital in Lausanne, Switzerland. The survey was administered to all eligible patients by the order of their scheduled appointments at the end of their medical visit. The BMQ comprises two subscores: Specific‐Necessity (5 identical items in BMQ‐f and BMQ‐HAART) and Specific‐Concerns (also 5 identical items in BMQ‐f and BMQ‐HAART). The subscores were standardized by dividing the score scale by the number of questions in the scale, resulting in a range of responses between 1 (low) and 5 (high). Self‐reported medication adherence was measured using the SHCS Adherence Questionnaire (SHCS‐AQ). Adherence was defined as not missing any dose or missing one dose of the treatment in the past 4 weeks. Sociodemographic variables were retrieved by reviewing the SHCS database.

Results

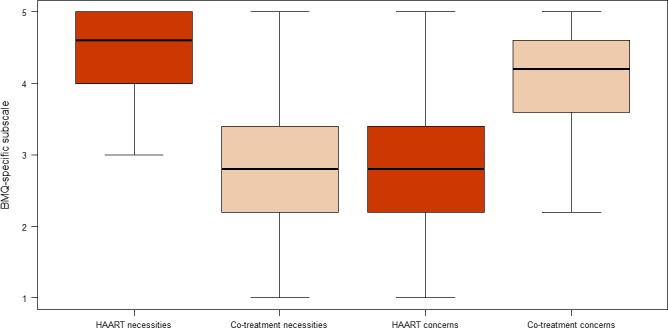

A response rate of 73% (109 of 150) was achieved. A total of 105 patients were included in the analysis: their median age was 56 [interquartile range (IQR) 51, 63] years and 74 were male (70%). Eighty‐seven patients (83%) were adherent to cART and 75 (71%) were adherent to their co‐treatments (P = 0.0001). The standardized mean responses for the BMQ Specific‐Necessity subscores were 4.46 [standard deviation (SD): 0.58] and 2.86 (SD: 1.02) for cART and co‐treatments, respectively (P < 0.0001). For Specific‐Concerns, the standardized mean responses were 2.9 (SD: 1.02) for cART and 4.09 (SD: 1.02) (P < 0.0001) for co‐treatments. cART and co‐treatment concerns increased as the number of co‐treatments increased (P = 0.03 and P < 0.0001, respectively).

Conclusions

Patients had higher Necessity and lower Concerns scores for their cART in comparison with their co‐treatments. A higher percentage of patients reported being adherent to cART compared with the co‐treatments that they reported they were most likely to miss. Further research using a bigger sample size and more objective measures of adherence is needed to explore the association between adherence and patients' perceptions.

Keywords: aging, antiretrovirals, comorbidity, HIV, medication adherence

Introduction

People living with HIV can have almost the same life expectancy as those without HIV infection as a result of the success of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) 1, 2. This results in an aging HIV‐infected population who are at risk of developing other chronic comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, kidney diseases and depression 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. This risk is probably associated with their age, persistent immune activation, chronic inflammation and also long‐term exposure to cART 9, 10. As disease‐specific guidelines recommend one or more additional medications for each diagnosis, this has resulted in a comorbid aging HIV‐infected population using polypharmacy 11, 12.

Medication adherence is defined as the process by which patients take their medications as prescribed by their health care providers 13, 14. It has three phases: initiation, which relates to the start of the treatment; implementation, which relates to the extent to which the patient follows the dosing regimen; and finally discontinuation, which relates to the interruption of treatment 13. However, it has been estimated that patients with chronic illness adhere only 50% of the time to their medication 15. Patients' nonadherence to their medication can be intentional or unintentional 16, 17. Intentional nonadherence can be viewed in the context of the social cognition theory which postulates that individuals develop beliefs that influence their interpretation of information and consequently their actions 18, 19. Unintentional nonadherence is less strongly associated with patients' beliefs than intentional nonadherence 20, 21.

In the context of chronic illness, the medication beliefs of patients have been associated with adherence to their treatment 17, 19, 22. Such research suggests that the key beliefs influencing patients' behaviour about their medication can be grouped in a Necessity‐Concerns Framework (NCF) 23. The necessity aspect describes the perceptions of patients' needs for their medication, while the concerns aspect describes their concerns about adverse consequences associated with taking their medication 23. Unless an intervention such as education is made to change patients' beliefs, the beliefs tend to be temporally stable, influencing long‐term medication‐taking behaviour 24. Furthermore, as culture and health care systems differ in different countries, patients' beliefs vary accordingly. From our experience in clinical practice, infectious disease (ID) physicians tend to emphasize cART as a priority with the risk of neglecting adherence support for co‐treatment. Hence, exploring patients' beliefs about their medication, especially among the comorbid HIV‐positive population in Switzerland, is important, as there is no published research on this. Our hypothesis is that patients' perceptions of and attitudes towards their cART, which is perceived as crucial to their survival, differ from their beliefs about their co‐treatments, and this may have an impact on their medication adherence.

Methods

Setting and study design

This prospective, observational cross‐sectional study was carried out at the Infectious Disease Service at the University Hospital in Lausanne, Switzerland and at the Community Pharmacy, Department of Ambulatory Care & Community Medicine, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. ID physicians are in charge of following up the patients once every 3–6 months. This does not include the initiation phase of treatment where the patients are followed up according to the International AIDS Society/European AIDS Clinical Society (IAS/EACS) treatment guidelines (i.e. more frequent visits upon initiation of treatment). ID physicians prescribe the antiretrovirals. Co‐treatments are prescribed either by them or by other specialists or the general practitioner (GP). Information about all chronic and “as needed” comedications is collected routinely in care through the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS). Antiretrovirals and co‐treatments are covered similarly by Swiss health insurance.

At the end of a routine follow‐up visit with their ID physician or nurse, patients were asked to complete a questionnaire (Appendix S1). They were informed that neither the physician nor the nurse would be able to view their responses. Filled‐in questionnaires were collected anonymously at a box at the reception desk. If patients preferred filling them in at home, they were provided with a pre‐stamped return envelope addressed to the data collector based at the community pharmacy. Telephone reminders were executed for patients who did not return their responses by post within 3 weeks of questionnaire administration by their ID physician to ensure privacy. Sociodemographic and clinical information about the patients was retrieved by reviewing the SHCS database 25.

Participants

All SHCS‐enrolled adult patients (> 18 years old) on cART for at least 1 year and on at least one concomitant oral medication from any therapeutic class for at least 6 months followed up at the Infectious Disease Service at Lausanne University Hospital in Switzerland were considered eligible. Pregnant women, patients who did not speak French (the language of administration of the questionnaire) and those who refused to participate were excluded. Sample size calculation for the questionnaire was performed using the raosoft website (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html), assuming a margin of error of 10%, a total population of SHCS patients in Lausanne with chronic comedication of approximately 400, as identified by the SHCS data manager, and a response distribution of 50%. The sample size calculation resulted in 78 patients as a representative sample of the Lausanne SHCS population. Consecutive recruitment of patients was carried out by the order of their scheduled visits with their treating physician or nurse, starting in July 2015 and ending when the estimated sample size and a target response rate of 70% were reached. Those patients who had missed and then rescheduled an appointment were still approached at their new appointments. However, those patients who did not reschedule their missed appointments during the time of the study were not included in the study.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Vaud in Switzerland (protocol number 166/15 on 26 May 2015). All patients received an information sheet explaining the study and were asked to sign a consent form. All data were anonymized and stored on a password‐protected computer.

Tools

Self‐reported medication adherence was measured for both cART and co‐treatments using the Swiss HIV Cohort Study Adherence Questionnaire (SHCS‐AQ) 26. It consists of two cross‐sectional questions measuring ‘taking adherence ‘and ‘Drug holidays’ which constitute the implementation component of adherence. ‘Taking adherence’ is defined as the number of missed doses in the last 4 weeks (daily, more than once a week, once a week, once every second week, once a month, or never). Drug holidays are defined as missing two or more consecutive doses in the last 4 weeks 27. For the co‐treatments, we asked the patients to respond according to the co‐treatment(s) they had a tendency to miss most if they were taking more than one co‐treatment, whereas for antiretrovirals they were asked to respond with regard to their entire treatment regimen.

Beliefs about cART were assessed using the validated French version of the Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire for Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (BMQ‐HAART) 28. In this article we will use cART and HAART interchangeably. For co‐medications, the French version of the generic Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ‐f) was used 28, 29, 30. Approval to use the BMQ was obtained from the developer (Robert Horne. Centre for Behavioural Medicine, The School of Pharmacy, University of London).

The French generic version (BMQ‐f) and BMQ‐HAART comprise 18 and 19 questions, respectively, which assess the patients' perceptions of their medication. The BMQ‐Specific, as described in the BMQ‐f, comprises two subscales: Specific‐Necessity and Specific‐Concerns. The Necessity scales of the generic BMQ‐f and BMQ‐HAART have five items in common. The Concerns scales of the generic BMQ and BMQ‐HAART also have five items in common. The difference between the generic BMQ and BMQ‐HAART is that BMQ‐HAART has three and six additional items on the Necessity and Concerns scales, respectively 28. The Necessity and Concerns scores for identical questions in the two questionnaires were compared. Cronbach's α for the original questionnaire was estimated at 0.80 for the BMQ‐f Specific‐Necessity subscale and as 0.82 for the BMQ‐f Specific‐Concerns subscale, which indicates high internal validity 28.

Data entry and analysis

Questionnaire data

The data were coded and entered using Microsoft Office Excel (2007). Each question of BMQ‐f and BMQ‐HAART is scored on a five‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). BMQ‐f and the first 10 questions of the BMQ‐HAART Specific‐Necessity and Specific‐Concerns subscales have five items, respectively, and scores ranging from 5 to 25 28. The subscales were standardized by dividing the scale score by the number of questions in the scale. Principal component factor analysis was conducted to confirm the underlying factor structure in BMQ‐HAART as the translation was validated in French but not the content. The criterion for factor extraction was an eigenvalue > 1.0.

The responses for BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f were reverse coded so that higher scores on the Specific‐Concerns scale represent stronger concerns about the potential negative effects of the medication and higher responses on the Specific‐Necessity represent stronger perceptions of personal need for the medication to maintain health now and in the future. This was done for all questions except for questions 13, 15 and 17 in BMQ‐HAART, according to their inverse phrasing. Means, standardized means, standard deviations (SDs), medians and lower−upper quartiles (Q1−Q3) were calculated for the BMQ subscales. As the BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f subscales consist of several statements, each with scores of 1–5, they were treated as continuous variables in all analyses to gain as much information as possible 28. Two‐sided t‐tests were used to compare individual subscale scores for antiretrovirals and co‐treatments as they were normally distributed.

Sociodemographic and clinical data

Descriptive analysis was carried out using median (Q1−Q3) or a count with percentage, as appropriate. Descriptive univariate analyses of the associations between demographic or clinical variables and individual BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f subscale scores, and between individual BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f subscale scores were performed using t‐tests, the Wilcoxon−Mann−Whitney test or Pearson's correlation test, as appropriate. The level of significance for all analyses was set at P < 0.05. Variables included in the final analysis were age, gender, education, ethnicity, sexual orientation, alcohol use, drug use, number of comedications, duration of HIV infection since diagnosis, HIV RNA viral load and CD4 count at the time of questionnaire administration. Education was dichotomized into above and below a bachelor's degree, which corresponds to 15 years of education. The detectable limit for HIV RNA was set to 50 HIV‐1 RNA copies/mL. Multivariate regression analysis was then performed using the BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f subscale scores as dependent variables and the significant sociodemographic variables from the test of association as predictors. The predictors were initially entered into the model and then eliminated one by one using the backward deletion method based on how insignificant they were. For these analyses, all items of BMQ‐HAART were used, unlike when comparing the scores of BMQ‐HAART and BMQ‐f, where we only compared the identical 10 items for precision.

Adherence data

Adherence was dichotomized into adherent and nonadherent. Patients were considered adherent if they reported that they had never missed a dose or missed only one dose over the past 4 weeks, as described by Glass et al. 27, and nonadherent if they had missed more than one dose. Associations between SHCS‐AQ and BMQ‐Specific responses for cART and co‐treatments and the Necessity‐Concerns differential were performed using the Wilcoxon−Mann−Whitney test or t‐test, as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed in Rstudio version 0.99.4 (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA).

Results

The study questionnaire was administered to 150 patients attending their visits at the Infectious Disease Service from July 2015 to January 2016. Out of 150 administered questionnaires, 109 patients returned their questionnaires (72.6%) and four declined to fill it in. Four questionnaires had more than 60% of the responses missing and therefore were excluded from the analysis, leaving a remainder of 105 questionnaires to be included in the analysis. As shown in Table 1, most participants were male (74%), which is similar to the general HIV‐infected population at the hospital. The median age was 56 years. Half of the participants were employed and almost three‐quarters (74.2%) had finished < 15 years of formal education. Eighty‐seven per cent of patients reported being adherent to cART and 75% of them reported being adherent to their co‐treatment (P = 0.0001). The descriptive values of the BMQ subscale scores are displayed in Fig. 1. Principal component factor analysis of BMQ‐HAART responses confirmed the underlying factor structure with the two factors necessities and concerns, as shown in Appendix S2.

Table 1.

Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

| Age | 56 (51, 63)a |

| Gender | |

| Male | 74 (70.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 88 (83.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than a bachelor's degree (< 15 years of education) | 78 (74.2) |

| Profession | |

| Employed | 50 (47.6) |

| Sexual preference | |

| Heterosexual | 62 (59) |

| Homosexual | 25 (23.8) |

| Source of HIV transmission | |

| Heterosexual | 45 (42.9) |

| Men who have sex with men | 41 (39) |

| Number of co‐treatments | |

| One | 19 (18) |

| Two | 27 (25) |

| More than two | 59 (56) |

| Therapeutic classes of co‐treatment | |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 79 (75.2) |

| Antidepressants | 44 (42) |

| Anxiolytics | 31 (29.5) |

| Anti‐osteoporosis drugs | 29 (27.6) |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs | 16 (15.2) |

| HIV laboratory and clinical data | |

| Undetectable HIV RNA (< 50 copies/mL) | 102 (97) |

| CD4 count nadir (cells/μL) | 137 (64, 257)a |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | 707 (502, 918)a |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (years) | 16.51 (11.6, 24.7)a |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| ≤ 1 time monthly | 52 (49.5) |

| 2−4 times monthly | 18 (17.1) |

| 2−3 times weekly | 18 (17.1) |

| Missing data | 17 (16.1) |

| Injecting drug user | 3 (2.8) |

| Adherence (self‐reported) | |

| Adherent to cART | 87 (82.9) |

| Adherent to co‐treatments | 75 (71.4) |

| Self‐reported co‐treatments patients would be most likely to forget or not take (if any)b | |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 14 (13.3) |

| Antidepressants and anxiolytics | 8 (7.6) |

| Anti‐osteoporosis drugs | 4 (3.8) |

| Oral antidiabetic drugs | 1 (0.95) |

| Morning doses of co‐treatments | 12 (11.4) |

| Noon‐time doses of co‐treatments | 5 (4.8) |

| Evening doses of co‐treatments | 17 (16.2) |

| All co‐treatments | 3 (2.9) |

| Total | 105 |

cART, combination antiretroviral therapy.

Values are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Expressed as median (Q1, Q3).

Patients had the options to select multiple answers and to write the name of the co‐treatment(s).

Figure 1.

BMQ‐specific subscale scores for HAART and co‐treatments. y‐axis: BMQ‐specific subscale. HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

The results of the tests of association between sociodemographic or clinical variables and the two individual BMQ subscale scores, and between the two individual BMQ subscale scores for co‐treatments and cART are listed in Table 2. Respondents had higher Necessity and lower Concerns scores for their cART in comparison with their co‐treatments. Women had higher cART Necessity scores than men. Respondents had higher Concerns and Necessity scores for co‐treatments if they were on more than two prescribed oral co‐treatments. The major prescribed co‐treatments were for cardiovascular disease (79%) followed by depression (44%). Respondents with an education level less than a bachelor's degree had higher Necessity scores for their co‐treatments than those with an education level higher than a bachelor's degree. Respondents also had higher Necessity scores for their co‐treatments the higher their CD4 count was.

Table 2.

Significant associations between Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ) subscale scores for combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and co‐treatments, and between sociodemographic and clinical variables and BMQ subscale scores (range 1−5)

| Mean difference (95% CI) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|

| Necessity subscale scores for cART and co‐treatmentsa | 1.6 (1.38, 1.82) | < 0.0001 |

| Concerns subscale scores for cART and co‐treatmentsa | 1.19 (0.97, 1.39) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender | ||

| cART Necessity score higher among women in comparison to menb | 0.2 (0.04, 0.35) | 0.020 |

| Number of co‐treatments (> 2) | ||

| Co‐treatment Concerns score higher if > 2 co‐treatmentsb | 0.37 (0.02, 0.71) | 0.036 |

| Co‐treatment Necessity score higher if > 2 co‐treatmentsb | 0.39 (0.02, 0.76) | 0.041 |

| Injecting drug use | ||

| cART Concerns score higher in injecting drug usersb | 0.2 (0.06, 1.5) | 0.040 |

| Education (≥ bachelor degree) | ||

| Co‐treatment Necessity score higher if less educationb | −0.62 (−1.05, −0.19) | 0.006 |

| CD4 count | ||

| Co‐treatment Necessity score higher by higher CD4 countc | 0.24 (0.05, 0.41) | 0.016 |

CI, confidence interval.

t‐test.

Wilcoxon−Mann−Whitney test.

Pearson correlation coefficient.

There was no significant association between adherence group and scores on the two BMQ subscales, i.e. Necessity and Concerns, for antiretrovirals (P = 0.706 and 0.8413, respectively) and co‐treatments (P = 0.325 and 0.721, respectively).

The multivariate analysis (Table 3), with gender, number of co‐treatments and CD4 count in one model together with education, showed that for each 1 unit increase in education, while keeping the other covariables constant, there was a decrease in Necessity score for co‐treatments. It also showed that the higher the number of prescribed co‐treatments, the higher the co‐treatment Necessity score.

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and co‐treatment Beliefs about Medicine Questionnaire (BMQ) subscale scores and sociodemographic and clinical covariables

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Estimate (SE) | Multivariate (P‐value) R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMQ generic Specific‐Necessity score (for co‐treatments) | (< 0.001) (adj.) R 2 = 0.19 | ||

| Gender | 0.67 | ||

| Number of co‐treatments | −0.09 (0.04) | 0.05 | |

| Education | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.001 | |

| CD4 count | −0.01 (0.0002) | 0.003 | |

| BMQ generic Specific‐Concerns score (for co‐treatments) | (0.052) R 2 = 0.07 | ||

| Gender | −0.34 (0.21) | 0.11 | |

| Number of co‐treatments | −0.10 (0.05) | 0.03 | |

| Education | 0.02 (0.39) | 0.65 | |

| Injecting drug use | 1.58 (0.86) | 0.07 | |

| BMQ‐HAART Specific‐Necessity score | (0.09) R 2 = 0.04 | ||

| Gender | −0.20 (0.009) | 0.04 | |

| Number of co‐treatments | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.13 | |

| CD4 count | −0.04 (0.0001) | 0.74 | |

| BMQ‐HAART Specific‐Concerns score | (0.0375) (adj.) R 2 = 0.07 | ||

| Number of co‐treatments | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.83 | |

| Education | 0.14 (0.06) | 0.01 | |

| CD4 count | −0.01 (0.0003) | 0.06 |

adj., adjusted; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; SE, standard error.

Regarding concerns about cART, the multivariate analysis showed that for every 1 unit increase in education, while keeping CD4 count and number of co‐treatments constant, there was a decrease in concerns about cART. However, the variables altogether explained very little of the variance in the dependent variable (low R 2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study on HIV‐infected patients' beliefs about all of their co‐treatments in comparison with their cART. A quarter of the patients (median age 56 years) had two prescribed co‐treatments and more than half of the patients (56.2%) had more than two co‐treatments in addition to their cART. This confirms that the aging HIV‐infected population is burdened with comorbidities, as described previously in the SHCS population 31 and in other HIV‐positive populations 32, 33, 34. The major comorbidity in our study was cardiovascular disease. It has been suggested that there is an earlier onset of cardiovascular disease among HIV‐positive compared with HIV‐negative adults 35. This is mainly due to the HIV population aging, but this earlier onset is also associated to the HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment 35. The second and third most common comorbidities among our study participants were depression and anxiety, conforming with findings in the literature on the prevalence of depression and anxiety among older HIV‐positive individuals 36. This might be related to loneliness and HIV‐related stigma 37.

Patients may not adhere to their therapy for several reasons, such as treatment complexity, side effects, a bad taste, a lack of motivation or interference with their daily routine 38. Optimal adherence levels vary across different chronic treatments. For example, 90% adherence is currently reported as optimal adherence to antiretroviral regimens, although this value may be slightly different for newer regimens 39. With the exceptions of infectious disease and oncology treatments, which carry risks of rapid and inexorable resistance emergence, no well‐defined threshold exists for other chronic treatments. For most treatments, the level of optimal adherence is defined through short‐ and long‐term clinical goals, and varies across patients, disease types and stages, and treatments. Moreover, for diseases other than HIV infection, the risk of suboptimal adherence is often perceived as being lower as adherence can be increased over time without major transient harm such as resistance. In our study, when patients were asked to report their adherence to their cART, our results showed that 82.9% of the patients reported having missed one dose or none of the prescribed doses. In contrast, 71.4% of the patients reported having missed one dose or none of their prescribed co‐treatments when asked to report their adherence to the co‐treatment they were most likely to miss (P = 0.0001). Hence, it is essential to explore the different beliefs about medicines of comorbid HIV‐infected patients which may influence their medication management strategies and decisions to adhere to their prescribed regimens.

Patients had higher Necessity and lower Concerns scores for their cART in comparison to their co‐treatments. The NCF provides an assessment of patients' perceptual barriers to adherence and has been demonstrated to predict adherence in different illness conditions 40. In addition, patients with chronic illness who hold positive beliefs about their cART were shown to demonstrate high adherence to cART 41. In our results, however, we did not find an association between patients' beliefs and adherence. We believe that patients may prefer to present themselves positively in terms of self‐reported adherence. This overestimation of adherence, together with the relatively small sample size, made it less likely that we would find an association between reported patient beliefs and adherence 23.

A perceived positive health change has been reported to be associated with positive views about medication 23. As the majority of patients had an undetectable viral load, with a median CD4 count of 707 cells/μL and a median CD4 count nadir of 137 cells/μL, the higher Necessity scores for cART could be explained by the perceived positive health change as a result of cART in this patient group. In addition, health care providers may focus more on cART adherence than on co‐treatments because of a fear of resistance and treatment failure, which can lead to mortality, whereas similar fears are not present with respect to co‐treatments.

The lower Concerns scores for cART could be attributable to the support given by health care providers to the patients, making sure that they receive all the necessary information about their cART and addressing any concerns they might have, which reduces their ‘concerns’ beliefs. Also, as our study population was mainly white and male, our patients might have experienced less HIV‐related anxiety as a consequence of stigmatization than their counterparts in African‐ or female‐dominated populations 42, 43. In contrast, the higher Concerns scores for co‐treatments can be attributed to the unfamiliarity of the patients with their co‐treatments in comparison to their cART, possibly because prescribers provided less information on their co‐treatments in comparison to their cART, and this may have influenced the patients' evaluation of the prescription 19, 44. Univariate analysis of the number of prescribed co‐treatments showed that, for more than two co‐treatments, the Necessity and Concerns scores for co‐treatments increased. The multivariate analysis showed that there was an increase in co‐treatment Necessity score with an increase in the number of co‐treatments. As the aging HIV‐infected population phenomenon is relatively new, very few studies have addressed specific management issues surrounding polypharmacy in this population. Our findings suggest that health care providers should understand the dynamic nature of adherence and that patients may need comprehensive adherence interventions taking the entire treatment into consideration.

Patients with education less than a bachelor's degree perceived a greater need for their co‐treatments compared with patients with higher education in the univariate and multivariate analyses. This counterintuitive result might be a consequence of patients with more education possibly being more likely to question their doctors' decisions regarding co‐treatment choices and believing that they know their disease and treatment options well, and are capable of making educated decisions about their therapy. In contrast, regarding concerns about cART, the multivariate analysis showed that adults with more education had fewer concerns about their cART compared with those with less education, which is intuitive despite the weak statistical association (small R 2). In the univariate analysis, the higher the CD4 count of the patient was, the greater was the perceived necessity of their co‐treatments. This indicates that the better controlled the HIV infection is, the greater is the perceived necessity of the patients' co‐treatments. None of the sociodemographic variables were shown to be significantly associated with adherence, which was also reported by Horne and Weinman, who stated that medication beliefs were more powerful in predicting nonadherence than sociodemographic and clinical variables 19.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include the novelty of the study in addition to the use of the SHCS database to capture sociodemographic and clinical information.

However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, this study population has unique characteristics, and a relatively small sample size, which may prevent the generalization of the findings to the general HIV‐positive population, even though it is representative of the Lausanne SHCS population, which is not different from the Swiss HIV‐infected population.

Secondly, as self‐reported adherence is known to be an overestimator of adherence 45, we believe that this was the reason that significant associations were not found between the two BMQ scores and adherence, together with the relatively small sample size. In addition, we assessed the self‐reported worst adherence for the co‐treatments as it was not feasible to ask the patients to fill in one questionnaire per co‐medication prescribed, as patients had several co‐treatments. This may have led to overestimation of the difference in adherence between cART and comedications. Thirdly, we collected the HIV clinical outcomes (viral load and CD4 count) but did not collect the clinical outcomes that are associated with comorbidities.

Therefore, in future research, we would like to conduct the analysis with larger sample sizes and using more objective measures of adherence such as pharmacy refill records or electronically monitored adherence. It would also be interesting to identify a method to evaluate different patient beliefs about various co‐treatments separately as ‘necessity’ beliefs vary from one treatment to another 46. This method should limit as much as possible the length of the questionnaire, as a lengthy questionnaire can be burdensome on respondents, which may have a negative impact on the quality of results. Currently, we are conducting a qualitative study on the perceptions of patients which will also help in the in‐depth understanding of this topic.

Conclusions

The demographic changes in the HIV‐positive population as a consequence of the success of cART have led to an aging HIV‐positive population. It is the duty of researchers and health care providers to help these patients achieve successful aging. In our study, we looked at the perceptual barriers to adherence to co‐treatments in comparison with cART through an NCF. Patients had higher Necessity and lower Concerns scores for their cART in comparison with their co‐treatments. Patients also had a higher adherence to cART in comparison to the co‐treatments they reported as being most likely to miss. Further research is needed to explore the association between adherence and patients' perceptions. Although our findings need confirmation, they suggest that it could be important to focus on patient beliefs to improve adherence to co‐treatments.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: (a,b) Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaires (BMQ‐f) and BMQ‐HAART and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study adherence questionnaire (SHCS‐AQ).

Appendix S2: Principal component analysis of BMQ‐HAART – Eigenvalue >1.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation to the Swiss HIV Cohort Study (SHCS Project 808, grant number 148522).

References

- 1. Lohse N, Hansen AB, Gerstoft J, Obel N. Improved survival in HIV‐infected persons: consequences and perspectives. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60: 461–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taiwo B, Hicks C, Eron J. Unmet therapeutic needs in the new era of combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV‐1. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65: 1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanco JR, Caro AM, Perez‐Cachafeiro S et al HIV infection and aging. AIDS Rev 2010; 12: 218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jung O, Bickel M, Ditting T et al Hypertension in HIV‐1‐infected patients and its impact on renal and cardiovascular integrity. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 2250–2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barelli S, Angelillo‐Scherrer A, Foguena AK, Periard D, Cavassini M. Controversies regarding the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases in HIV patients. Rev Med Suisse 2011; 7: 905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maccaferri G, Cavassini M, Berney A. Mood disorders in HIV patients: a challenge for liaison psychiatry consultation. Revue Med Suisse 2012; 8: 362–364, 6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balderson BH, Grothaus L, Harrison RG, McCoy K, Mahoney C, Catz S. Chronic illness burden and quality of life in an aging HIV population. AIDS care 2013; 25: 451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collaboration ATC. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high‐income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet 2008; 372: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kowalska JD, Reekie J, Mocroft A et al Long‐term exposure to combination antiretroviral therapy and risk of death from specific causes: no evidence for any previously unidentified increased risk due to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2012; 26: 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alcaide ML, Parmigiani A, Pallikkuth S et al Immune activation in HIV‐infected aging women on antiretrovirals—implications for age‐associated comorbidities: a cross‐sectional pilot study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e63804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moen J, Norrgård S, Antonov K, Nilsson JLG, Ring L. GPs' perceptions of multiple‐medicine use in older patients. J Eval Clin Pract 2010; 16: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marzolini C, Back D, Weber R et al Aging with HIV: medication use and risk for potential drug–drug interactions. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 2107–2111. dkr248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA et al A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 73: 691–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta‐analysis. Med Care 2002; 40: 794–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sabate E. Adherence to Long‐Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lehane E, McCarthy G. Medication non‐adherence–exploring the conceptual mire. Int J Nurs Pract 2009; 15: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Horne R, Weinman J, Barber N et al Concordance, adherence and compliance in medicine taking. London: NCCSDO. 2005;2005:40–46.

- 18. Lehane E, McCarthy G. Intentional and unintentional medication non‐adherence: a comprehensive framework for clinical research and practice? A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud 2007; 44: 1468–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horne R, Weinman J. Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res 1999; 47: 555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wroe AL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence: a study of decision making. J Behav Med 2002; 25: 355–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lowry KP, Dudley TK, Oddone EZ, Bosworth HB. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence to antihypertensive medication. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39: 1198–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Phatak HM, Thomas J III. Relationships between beliefs about medications and nonadherence to prescribed chronic medications. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40: 1737–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients' adherence‐related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long‐term conditions: a meta‐analytic review of the Necessity‐Concerns Framework. PLoS One 2013; 8: e80633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Porteous T, Francis J, Bond C, Hannaford P. Temporal stability of beliefs about medicines: implications for optimising adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 79: 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Study SHC . Cohort profile: the Swiss HIV Cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39: 1179–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glass TR, De Geest S, Weber R et al Correlates of self‐reported nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV‐infected patients: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 41: 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glass TR, Battegay M, Cavassini M et al Longitudinal analysis of patterns and predictors of changes in self‐reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 54: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Horne R, Buick D, Fisher M, Leake H, Cooper V, Weinman J. Doubts about necessity and concerns about adverse effects: identifying the types of beliefs that are associated with nonadherence to HAART. Int J STD AIDS 2004;15:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999; 14: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fall E, Gauchet A, Izaute M, Horne R, Chakroun N. Validation of the French version of the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire)(BMQ) among diabetes and HIV patients. Eur Rev Appl Psychol 2014; 64: 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hasse B, Ledergerber B, Furrer H et al Morbidity and aging in HIV‐infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodriguez‐Penney AT, Iudicello JE, Riggs PK et al Co‐morbidities in persons infected with HIV: increased burden with older age and negative effects on health‐related quality of life. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013; 27: 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu P‐Y, Chen M‐Y, Hsieh S‐M et al Comorbidities among the HIV‐infected patients aged 40 years or older in Taiwan. PLoS One 2014; 9: e104945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao H, Goetz MB. Complications of HIV infection in an ageing population: challenges in managing older patients on long‐term combination antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 1210–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Petoumenos K, Worm SW. HIV infection, aging and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology and prevention. Sex Health 2011; 8: 465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Skapik J, Treisman G. HIV, psychiatric comorbidity, and aging. Clin Geriatr 2007; 15: 26. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV‐related stigma explain depression among older HIV‐positive adults. AIDS care 2010; 22: 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De Geest S, Sabate E. Adherence to long‐term therapies: evidence for action. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2003; 2: 323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse‐transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43: 939–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foot H, La Caze A, Gujral G, Cottrell N. The necessity–concerns framework predicts adherence to medication in multiple illness conditions: a meta‐analysis. Patient Educ Couns 2015; 99: 706–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P et al Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta‐analysis. BMC Med 2014; 12: 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCoy K, Higgins M, Zuñiga JA, Holstad MM. Age, stigma, adherence and clinical indicators in HIV‐infected women. HIV/AIDS Res Treat 2015; 2015: S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol 2013; 68: 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss‐Morris R, Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health 1996; 11: 431–445. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stirratt MJ, Dunbar‐Jacob J, Crane HM et al Self‐report measures of medication adherence behavior: recommendations on optimal use. Transl Behav Med 2015; 5: 470–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stack RJ, Bundy C, Elliott RA, New JP, Gibson JM, Noyce PR. Patient perceptions of treatment and illness when prescribed multiple medicines for co‐morbid type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2011; 4: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: (a,b) Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaires (BMQ‐f) and BMQ‐HAART and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study adherence questionnaire (SHCS‐AQ).

Appendix S2: Principal component analysis of BMQ‐HAART – Eigenvalue >1.