Abstract

Objective

The Lewy body dementias (LBD, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia) are the second most common cause of neurodegenerative dementia but remain under‐recognised, with long delays from initial assessment to diagnosis. Whilst validated instruments have been developed for key symptoms, there is no brief instrument for overall diagnostic assessment suitable for routine practice. We here report the development of such assessment toolkits.

Methods

We developed the LBD assessment toolkits in three stages. First, we conducted a systematic search for brief validated assessments for key symptoms and combined these into draft instruments. Second, we obtained feedback on acceptability and feasibility through two rounds of interviews with our patient and public involvement group. This led to modification of the toolkits. Finally, we piloted the toolkits in a feasibility study in routine dementia and Parkinson's disease services to produce final instruments suitable for routine clinical practice.

Results

Eleven clinicians, working in both dementia/memory assessment and Parkinson's disease/movement disorder services, consented to pilot the assessment toolkits and provide feedback on their feasibility. Clinicians worked in routine health service (not academic) settings and piloted the draft toolkits by integrating them into their regular clinical assessments. Feedback obtained informally, by written comments and through qualitative interviews led to modifications and production of final acceptable versions.

Conclusions

We were able to address an important need, the under‐diagnosis of LBD, by developing toolkits for improving the recognition and diagnosis of the LBD, which were acceptable to clinicians working in routine dementia and Parkinson's disease services. © 2016 The Authors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease dementia, toolkits, assessment

Introduction

The accurate recognition of dementia and the diagnosis of subtype of dementia ensure appropriate management and are central to improving patient care for those with dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common cause of degenerative dementia in older people after Alzheimer's disease (Stevens et al., 2002). Dementia also develops in up to 80% of people with Parkinson's disease, (PDD) (Aarsland et al., 2003)]. Prevalence estimates from both clinical and epidemiological samples of Parkinson's disease (PD) subjects indicate that at least 30% of those with PD have dementia (Riedel et al., 2010), whilst longitudinal study shows that 80% of those with PD will eventually develop dementia (Aarsland et al., 2003). PDD and DLB together are known as Lewy body dementias (LBD) because they share common clinical features, have closely overlapping neurobiology and respond to similar management approaches (Aarsland et al., 2004). Taken together, LBD accounts for 10–15% all cases of dementia (Stevens et al., 2002), affecting around 100,000 people in the UK. Whilst both DLB and PDD share the problems of under‐recognition and inappropriate management, the reason for these problems differs between DLB and PDD.

Despite the known prevalence of DLB, it has been estimated that only around one in three cases are currently detected in routine care in the UK (Alzheimer Society, 2007); for every DLB case properly diagnosed, another two are either not detected or misdiagnosed, usually as Alzheimer's disease. Furthermore, the route to diagnosis for patients with DLB is often protracted with one US study reporting that half of the patients had more than 10 clinic visits before the correct diagnosis was made(Galvin et al., 2010)]. There are several reasons for these difficulties with recognition including lack of assessment of key clinical symptoms such as hallucinations, fluctuation and sleep disorder in dementia assessment services and the challenges in eliciting motor features of parkinsonism in those with dementia (Ballard et al., 1997).Changing practices in dementia assessment services also mean that initial assessments are often carried out by non‐medical staff who are not able to perform neurological examinations.

Improving the accuracy of detection and diagnosis of PDD raises related but also distinct issues. Although patients with PD are often under regular follow‐up in neurology or geriatric medicine services only around one in three of those with PDD are currently recognised and diagnosed(Dujardin et al., 2010), and usually late in their illness. Again, there are several reasons for missed and delayed diagnosis of PDD: (1) cognitive impairment develops insidiously and at a variable time after PD diagnosis; (2) initial symptoms such as fluctuation, attentional problems and hallucinations may be thought to be related to medication side effects; (3) there is a general lack of awareness of the benefits of diagnosing dementia and a reluctance of professionals to disclose the diagnosis; (4) cognition is often not routinely assessed in neurology and geriatric medicine clinics. As with DLB, the recognition of dementia in PD brings the clear management benefits recognised for all those with dementia, including allowing the prescription of anti‐dementia medication, provision of support, education and advice, access to services, financial and other benefits and opportunities for future planning and attending to medico‐legal issues(O'Brien et al., 2011).

Considerable progress has been made in developing quick and validated tools for the assessment of key clinical symptoms of LBD, e.g. the Lewy Body Composite Risk Score (LBCRS) (Galvin, 2015). However, there is no single, simple to administer toolkit which incorporates the range of clinical symptoms and which can be used by clinicians broadly, e.g. the LBCRS assumes clinical expertise not necessarily present in the staff carrying out assessments in many clinics, and the LBCRS does not directly link to the diagnostic criteria for DLB. Hence, a brief assessment toolkit is needed, which is suitable for use in routine practice by all clinical staff. We report here the development of such toolkits as part of a feasibility study to improve the recognition and diagnosis of both DLB and PDD as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ‘Improving the diagnosis and management of neurodegenerative dementia of Lewy body type’ study (DIAMOND Lewy study).

Methods

We developed the LBD assessment toolkits in three stages. First, we identified brief validated assessments for different symptoms and signs that are key to making an LBD diagnosis and then combined these into a pilot instrument. Second, we obtained feedback on the acceptability and feasibility of the toolkit through interviews with patients, carers, clinicians and the programme patient and public involvement (PPI) group. This was used to modify the toolkits prior to piloting. Finally, we piloted the toolkits in a feasibility study in Dementia and PD services and modified the instrument to a final acceptable version suitable for use in routine clinical practice.

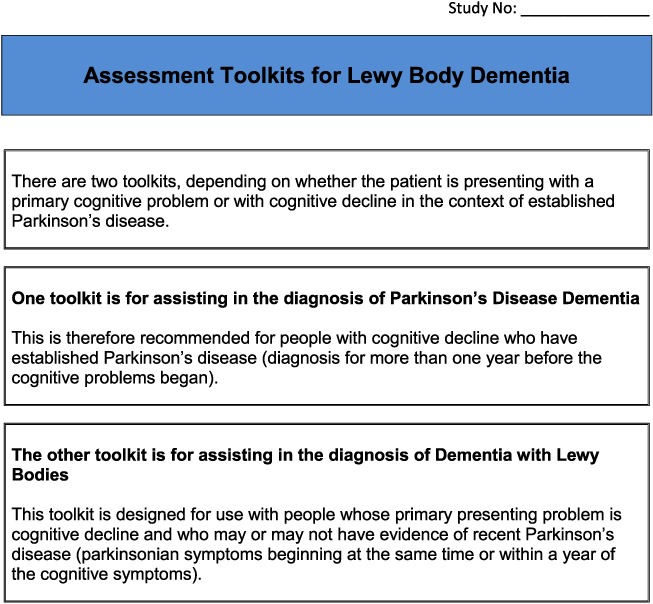

Development of pilot assessment tools

Clinical experts (AJT, JPT, IM, LA, DB and JOB) reviewed the published literature and supplemented this by their expert knowledge to identify available validated assessments instruments (Ballard et al., 1997; Mosimann et al., 2008; Boeve et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014). Following funding, the DIAMOND Lewy programme management group (PMG) first discussed the basic approach to the problem and, building on this evidence, concluded two different instruments would be needed, one for DLB and one for PDD. These would be matched to the international diagnostic criteria for DLB (McKeith et al., 2005) and PDD(Emre et al., 2007). The PMG identified appropriate components for each toolkit from the identified assessment instruments.

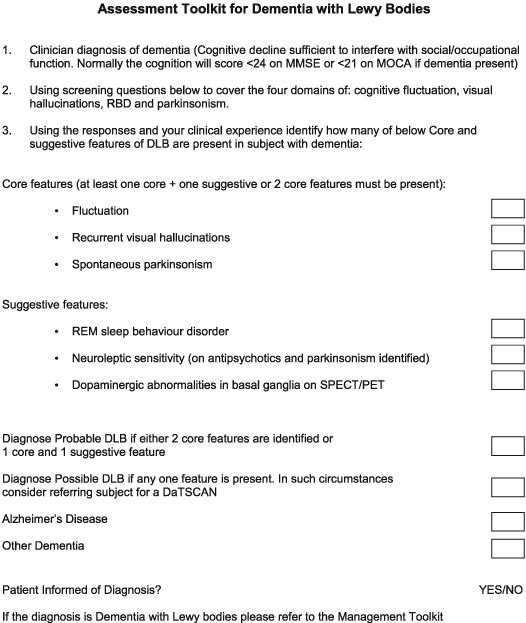

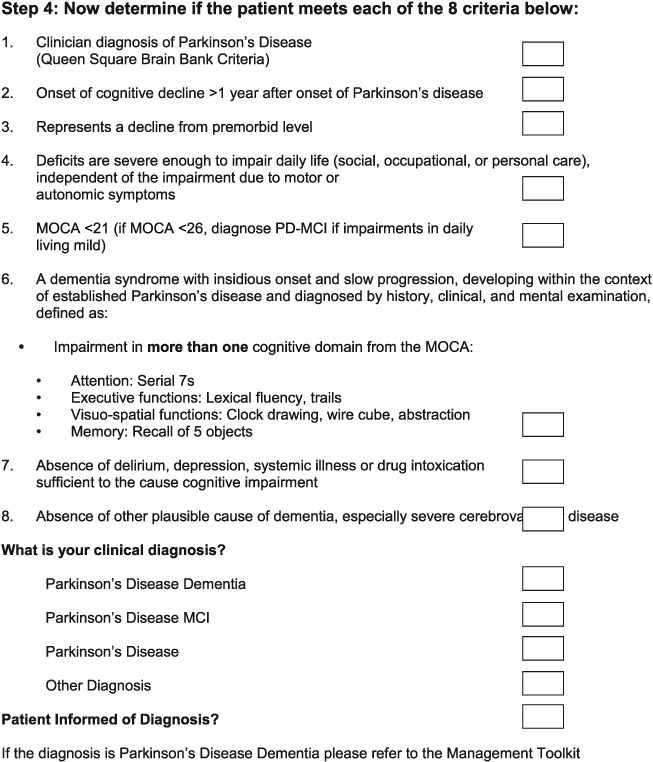

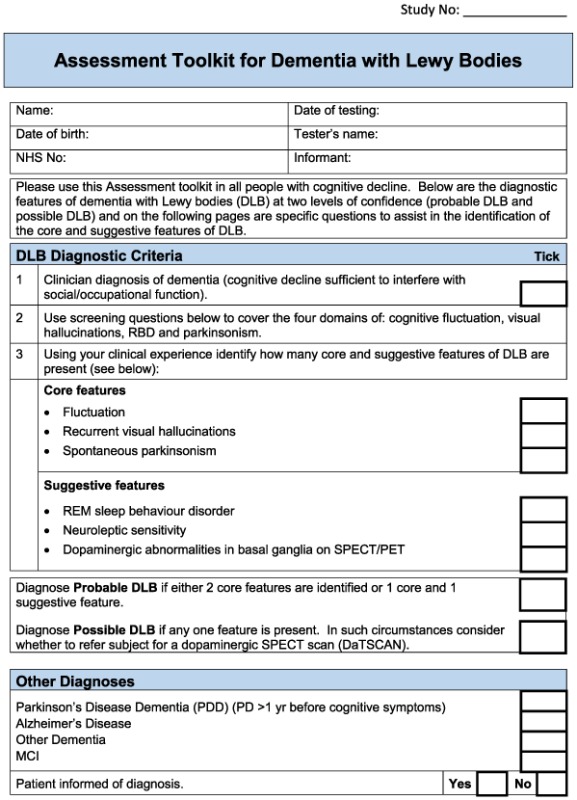

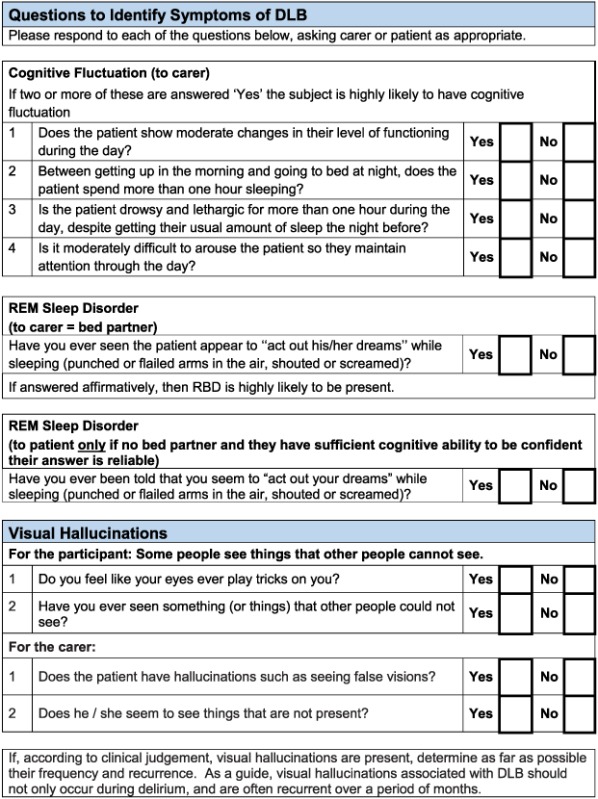

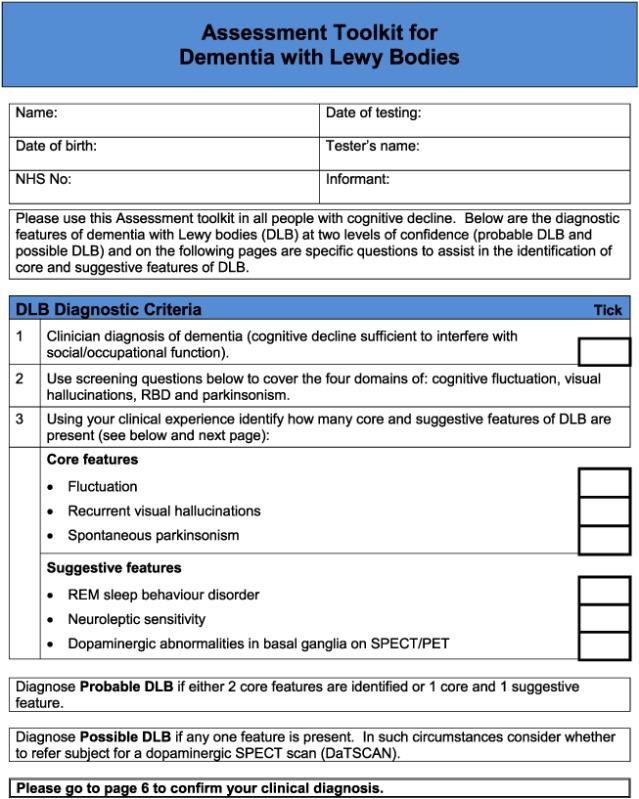

For the DLB toolkit, the aim was to improve identification of the core and suggestive diagnostic symptoms, because diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in specialist dementia services is not a concern. There are six core and suggestive symptoms for diagnosing DLB. One is dopaminergic imaging, which would not form part of a clinical assessment tool, and another is neuroleptic sensitivity which can only be identified following exposure to antipsychotic drugs, which is now a rare event (Walker et al., 2015). Hence, the focus was on assessment of the four remaining symptoms: persistent complex visual hallucinations, spontaneous cognitive fluctuations, spontaneous parkinsonism and Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder (RBD). The following components of the instrument were identified:

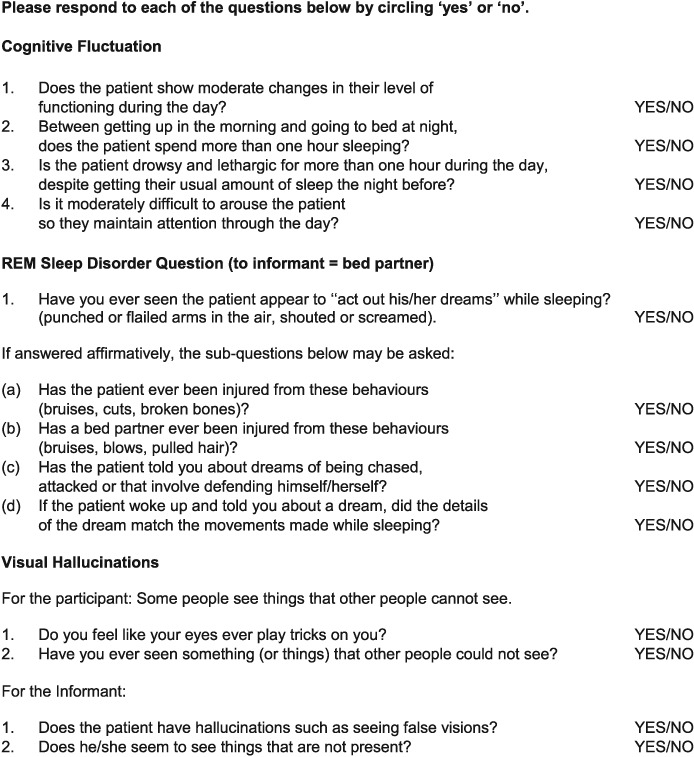

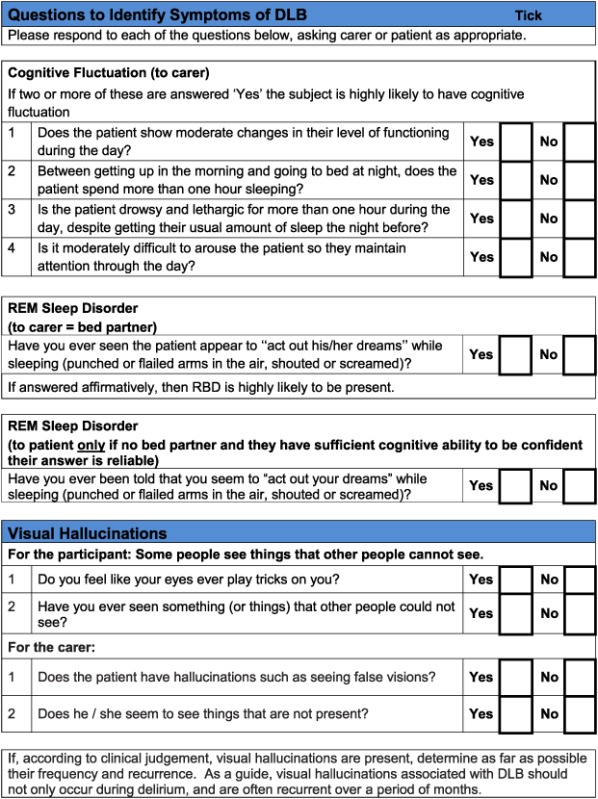

Cognitive fluctuation. Four questions to carers from the Dementia Cognitive Fluctuation Scale (Lee et al., 2014).

Rapid eye movement. A single screening question to carers from the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire (Boeve et al., 2011).

Visual hallucinations. Two core questions for patients and two for carers from the North East Visual Hallucinations Inventory (Mosimann et al., 2008).

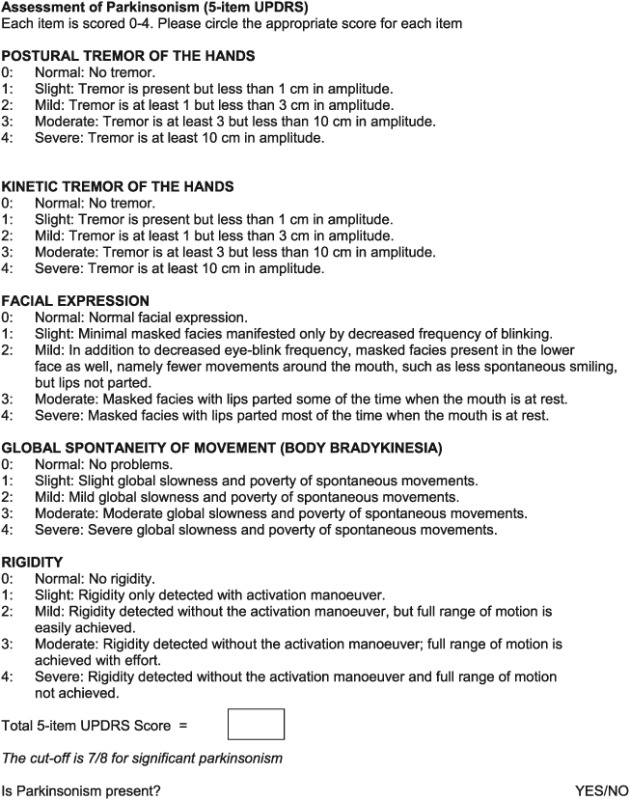

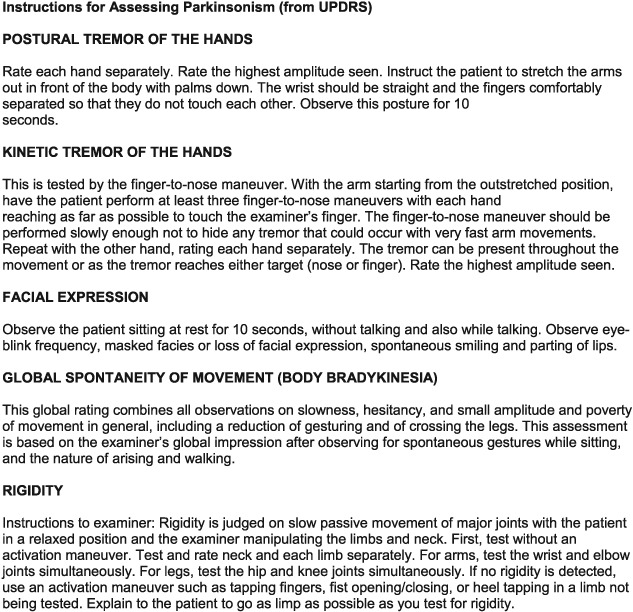

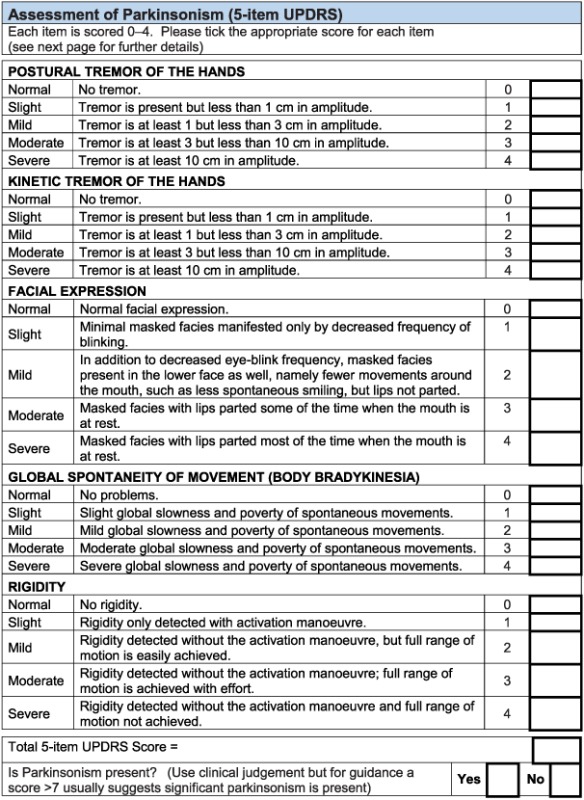

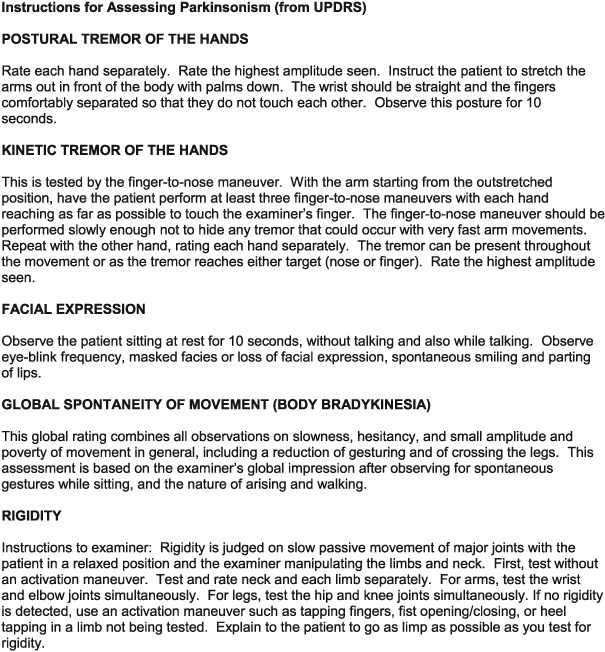

Motor features of parkinsonism: five items from the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (Ballard et al., 1997).

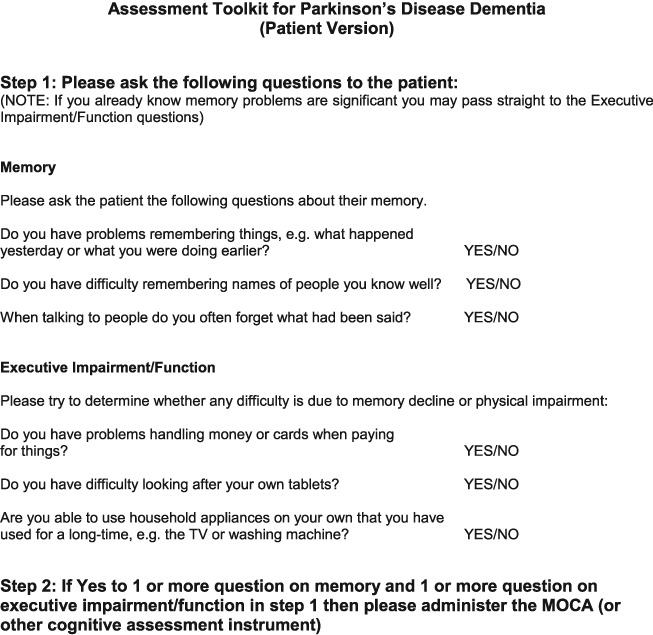

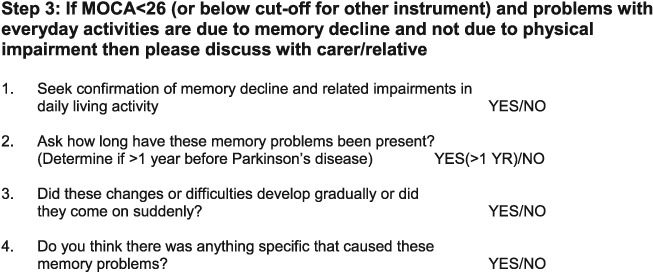

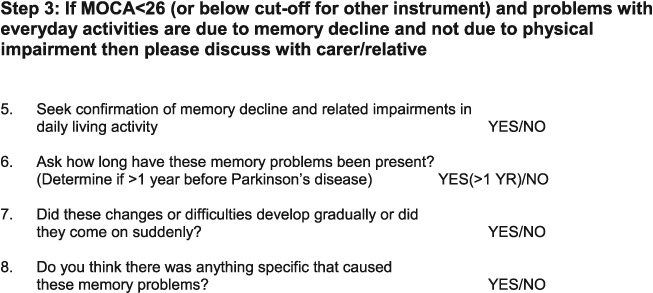

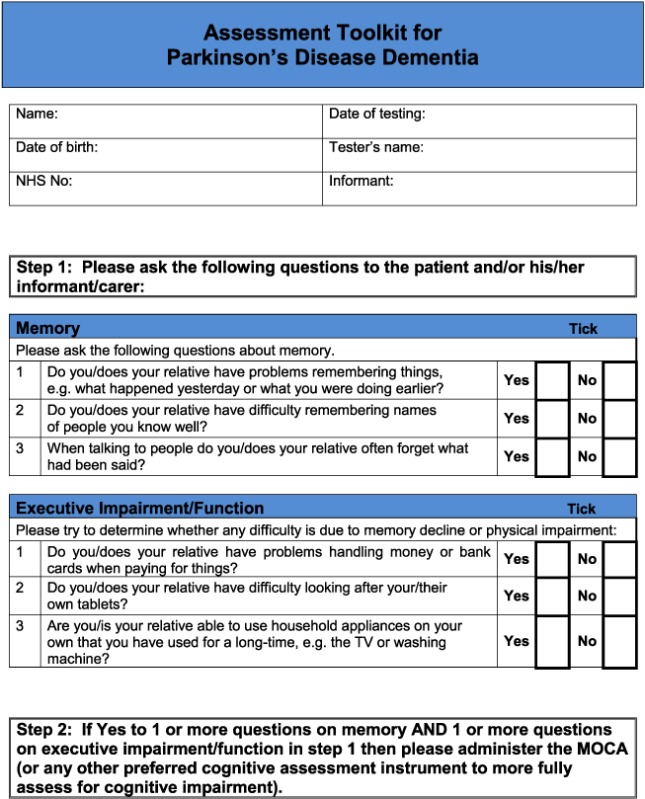

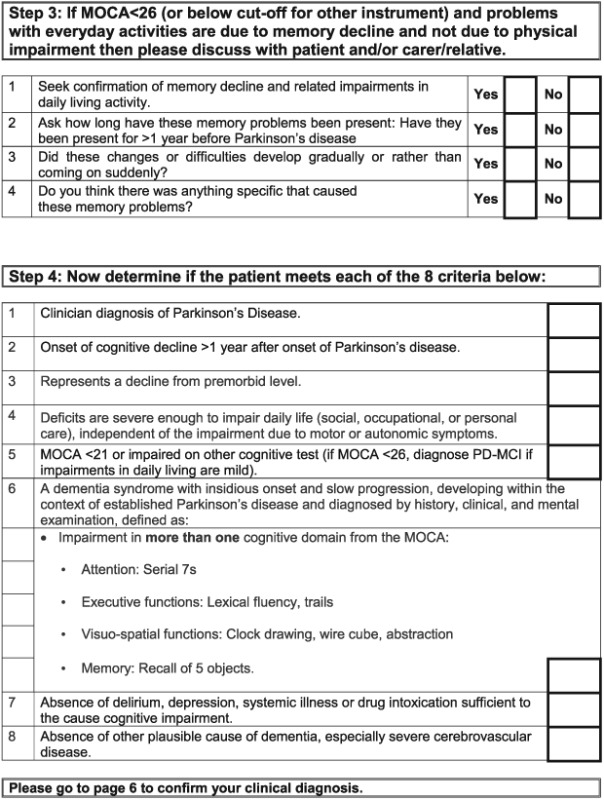

For the PDD tool, the aim was to improve identification of cognitive impairment and to facilitate matching of symptoms to the PDD diagnostic criteria (Emre et al., 2007). The Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) was identified as most appropriate for brief cognitive assessment in this context (Nasreddine et al., 2005).

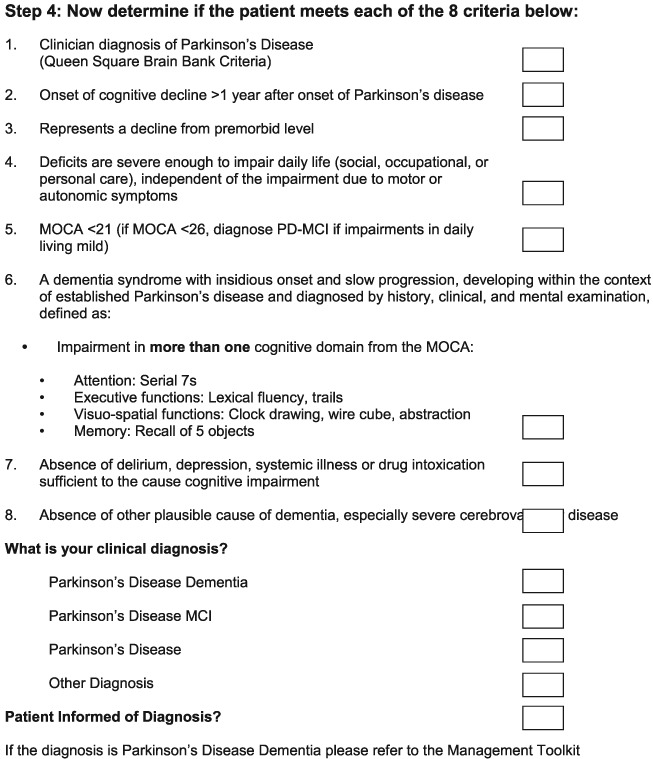

AT then put together the two instruments and after iteration with the rest of the PMG, a draft version was sent to the PPI panel. The PPI panel, including patients and carers, then contributed comments, and this feedback was incorporated into a revised version which was again commented on by the PPI members until a final agreed version and text was agreed for the pilot study. These two iterative rounds led to changes in wording of questions to try and improve clarity, and the major change suggested was to separate the PDD tool into one version for use with carers and one for use with patients, based on how patients present to PD services where they may or may not have a carer present. After final iterations between PMG and PPI groups, three final assessment toolkits were produced for the pilot and feasibility study (Appendix 1)

Pilot and feasibility of assessment toolkits

A pilot and feasibility study of the assessment instruments was carried out within Gateshead Health NHSFT, a representative Trust which provides old age psychiatry (memory/dementia) services (OAP) and PD (movement disorder) services. Following ethical and research and development approvals from Gateshead Health NHSFT, medical and nursing staff were identified in the OAP and PD services and given brief information about the study and brief training in using the assessment tools. The aims of the pilot was to ensure that the diagnosis tools were acceptable to staff and could be integrated into current assessment procedures in busy clinical services. Piloting was to include all subjects having first assessments for memory impairments and/or dementia because of possible Alzheimer's disease or other causes in the OAP service, and in the PD Service, all those with PD where any cognitive impairment was suspected. The aim was to include at least four staff (doctors and nurses) in each service and at least 20 subjects per service. Completed assessment toolkits were kept by the research team with copies placed in the patient notes.

Results

Four OAP consultants and four Elderly Medicine PD clinicians (two specialist nurses and two consultants) agreed to take part initially. Three additional clinicians who were on leave or not initially working within the service were subsequently recruited (two specialist registrars within the OAP service and one consultant from the PD Service) to increase opportunities for accrual.

Patient recruitment

The number of patients consenting for the use of the tool(s) by individual clinicians ranged from zero to seven. Two PD clinicians did not use the assessment tool (one clinician moved from the service soon after the pilot study started, the other felt it was not appropriate for any of their patients) but a later PD clinician did. All OAP clinicians used the assessment tool at least once. Clinicians working in OAP recruited more patients (a total of 19) than their colleagues in the PD service (a total of seven).

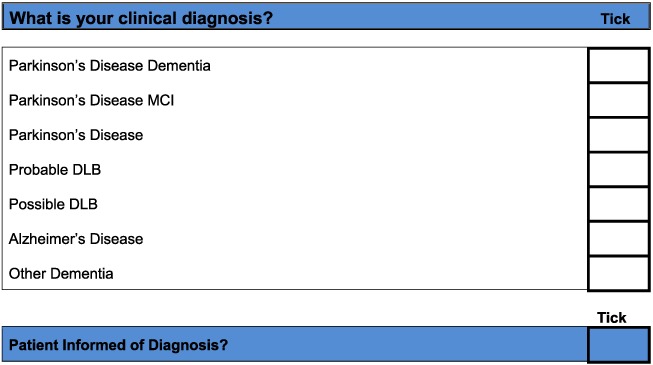

The toolkits were used with patients with and without LBD (Table 1). One patient had diagnoses of both vascular dementia and PD, and therefore, the total number of diagnoses was 27. Patients with PD may be seen by the OAP service and the movement disorder service, and during the study period, one patient was seen by both services at different times and completed the appropriate assessment tool in each service.

Table 1.

Diagnoses of participating patients

| Possible/probable DLB | Non‐DLB ‐ other diagnoses including depression, vascular dementia and mild cognitive impairment | PDD or PD‐MCI | Parkinson's disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of tool(s) | 5 | 12 | 2 | 8 |

| Qualitative interview | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; PDD, Parkinson's disease dementia; PD‐MCI, Parkinson's disease‐mild cognitive impairment.

Feedback and modification of the assessment toolkits

Feedback from clinicians was obtained in a number of ways:

Informal feedback to the local chief investigator (AT) and the research nurse

Writen comments on completed assessment tools

Quaitative interviews (CB).

For the patients, none of the questions from the assessment toolkits stood out as being inappropriate or unclear. For clinicians generally, the tools were found to be straightforward to use, with the constraints being on time available within current service structures. The PD service in particular found it difficult to integrate a cognitive assessment into their initial patient assessment. The toolkits were regarded as helpful in encouraging the assessment of the relevant symptoms for diagnosis and useful in providing structure and a specific approach.

Based on detailed feedback in these ways, the pilot toolkits were modified as follows (final DLB and PDD assessment toolkits are in Appendices 2 and 3, respectively). PD clinicians felt it would be helpful to have questions on core and suggestive symptoms of DLB in the PDD toolkit and did not feel that in practice, there was a need to have separate carer and patient versions of the PDD tool. Hence, the revised final version for PD services (Appendix 3) is titled ‘Assessment toolkits for Lewy body dementia’ and includes two toolkits, depending on whether the patient has longstanding PD and recent cognitive decline or whether the PD diagnosis/symptoms are recent, along with cognitive symptoms. A specific issue raised for RBD was what to do if no bed‐partner was available to answer the RBD question. AT contacted Dr Brad Boeve (Mayo Clinic, Minnesota) who had developed the RBD instrument and was advised that a similar question can be used with patients who are mildly cognitively impaired about any known history of ‘acting out dreams’. This additional option was therefore included in the final versions. In the pilot version of the PD toolkits, the MoCA had been specified. However, PD nurses were not familiar with the MoCA, although they aimed to complete an Mini‐Mental State Examination annually with each patient, and clinicians suggested that it be clarified that other cognitive instruments could be used if these were preferred, which has been performed in the final LBD toolkit. A third specific concern was that the wording, whilst clear, sometimes appeared prescriptive and seemed to not allow clinical judgement about the presence of symptoms, and so the wording has been changed at several points to make it clear that the questions in the toolkits are a guide, and ultimately, the presence of key symptoms, like final diagnoses, is a clinical judgement based on all available evidence. Several other more minor issues were raised about the layout and format which have been incorporated into the final versions of the toolkits, e.g. consistent use of tick boxes and an expanded list of diagnostic options for people with cognitive impairment.

Thus, following the pilot feedback led to changes in the assessment instruments. Specifically, a single PD assessment toolkit was produced which included the questions from the DLB toolkit for identifying visual hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations and RBD. Wording was also changed as was some of the layout in response to comments.

Discussion

We were able to combine elements from validated symptom assessment instruments into assessment toolkits for improving the diagnosis of DLB and PDD. These toolkits were developed to be aligned with the standard diagnostic criteria for these dementias (McKeith et al., 2005; Emre et al., 2007), and our feasibility study proved to be broadly acceptable to clinicians in regular clinical services and easily integrated into routine care making them ‘invisible’ to patients during clinical assessments. The piloting of these toolkits identified a few key changes, such as the desire for a combined LBD toolkit for use with both patients and carers in PD services, and the addition of an RBD question for use when no bed‐partner is available.

The study aimed to address the problem of inadequate recognition and diagnosis of both DLB (Galvin et al., 2010; Alzheimer Society, 2007) and PDD (Dujardin et al., 2010) and self‐consciously sought to build on existing evidence by utilising previously researched and validated instruments (Ballard et al., 1997; Mosimann et al., 2008; Boeve et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014). We did not therefore seek to assess the psychometric properties of the specific elements of the toolkits; rather we sought to address the need to combine these instruments into clinically useful and usable toolkits for clinicians working in dementia and PD services. Following this feasibility study, the toolkits will require further testing in other clinical populations to examine if they do indeed improve the diagnosis of LBD. Although the absence of validation may be regarded as a limitation, the fact the components have been tested and validated previously provides some reassurance. The piloting of these toolkits in a single organisation may also be regarded as a limitation of this study. Finally whilst we had an adequate number of OAP clinicians using the toolkits, we only had three PD clinicians. Whilst our study was deemed to have reached saturation, we acknowledge that future assessments of these toolkits will require more PD clinicians. However, the aim was to improve utility of the instruments in routine dementia, and PD services and the clinicians involved were not academics or researchers and are representative of clinicians in such services in the UK. Furthermore, it was clear from the feedback that we had reached saturation, making it unlikely that involvement of additional clinicians would have contributed usefully to the study. Although the instruments were not themselves regarded as burdensome, the intense pressure on clinicians' time sometimes made it difficult for them to use them, raising questions about how current service designs might be hindering high quality diagnostic assessments. One consequence of such pressures is that nursing staff are often conducting parts of the clinical assessments in many services and in order to assess Parkinsonism they require specialist training.

In conclusion, we sought to address an important need with this study, namely the under‐recognition and under‐diagnosis of LBD in routine services. We have performed this by developing brief and usable instruments which can be integrated into routine clinical practice. The pilot versions proved acceptable to clinicians and patients, and we encourage the use of the final versions to improve the diagnostic rates of DLB and PDD.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Key points.

Lewy body dementias are under‐recognised

Validated key questions improve identification of LBD

New toolkits facilitate recognition and diagnosis of LBD

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIHR under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (DTC‐RP‐PG‐0311‐12001); the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Lewy Body Dementia and Biomedical Research Centre awarded to Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University; and the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Dementia and the Biomedical Research Centre awarded to Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Cambridge.

We are grateful to Derek Forster for his contributions to the development of the assessment toolkits and to Bryony Storey for assisting in the pilot study. We thank the clinicians in Gateshead Health NHSFT who participated in the pilot study: Richard Harrison; Anitha Howard; Fariba Mahin Baiei; Andrew Ntanda; Apsara Panikkar; Imogen Forbes; Helen O'Connell; and Richard Athey.

We thank Dr Boeve and Dr Mosimann for their permission to include their questions in the toolkits.

Appendix 1. Draft Toolkits for the Lewy Body Dementias

Appendix 2. Assessment Toolkit for Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Appendix 3. Assessment Toolkits for Lewy Body Dementia

Thomas, A. J. , Taylor, J. P. , McKeith, I. , Bamford, C. , Burn, D. , Allan, L. , and O'Brien, J. (2017) Development of assessment toolkits for improving the diagnosis of the Lewy body dementias: feasibility study within the DIAMOND Lewy study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 32: 1280–1304. doi: 10.1002/gps.4609.

References

- Aarsland D, Andersen K, Larsen JP, Lolk A, Kragh‐Sorensen P. 2003. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease: an 8‐year prospective study. Arch Neurol 60: 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland D, Ballard CG, Halliday G. 2004. Are Parkinson's disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies the same entity? J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol 17: 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Society . 2007. Alzheimer Society. Dementia UK: A report on the Prevalence and Economic Cost of Dementia. London School of Economics and the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London: London. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C, McKeith I, Burn D, et al 1997. The UPDRS scale as a means of identifying extrapyramidal signs in patients suffering from dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neurol Scand 96: 366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, et al 2011. Validation of the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in an aging and dementia cohort. Sleep Med 12: 445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin K, Dubois B, Tison F, et al 2010. Parkinson's disease dementia can be easily detected in routine clinical practice. Mov Disord 25: 2769–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, et al 2007. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 22: 1689–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE. 2015. Improving the clinical detection of Lewy body dementia with the Lewy Body Composite Risk Score. Alzheimers Dement 1: 316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, et al. 2010. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 16: 388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, McKeith IG, Mosimann U, et al 2014. The Dementia Cognitive Fluctuation Scale, a new psychometric test for clinicians to identify cognitive fluctuations in people with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr 22: 926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al 2005. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 65: 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann UP, Collerton D, Dudley R, et al 2008. A semi‐structured interview to assess visual hallucinations in older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23: 712–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al 2005. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JT, Burns A, BAP Dementia Consensus Group . 2011. Clinical practice with anti‐dementia drugs: a revised (second) consensus statement from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 25: 997–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel O, Klotsche J, Spottke A, et al 2010. Frequency of dementia, depression, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms in 1,449 outpatients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol 257: 1073–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T, Livingston G, Kitchen G, et al. 2002. Islington study of dementia subtypes in the community. Br J Psychiatr 180: 270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker Z, Moreno E, Thomas A, et al 2015. Clinical usefulness of dopamine transporter SPECT imaging with 123I‐FP‐CIT in patients with possible dementia with Lewy bodies: randomised study. Br J Psychiatr, 206(2): 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]