Abstract

Background

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) can be debilitating, difficult to treat, and frustrating for patients and physicians. Real‐world evidence for the burden of CSU is limited. The objective of this study was to document disease duration, treatment history, and disease activity, as well as impact on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and work among patients with inadequately controlled CSU, and to describe its humanistic, societal, and economic burden.

Methods

This international observational study assessed a cohort of 673 adult patients with CSU whose symptoms persisted for ≥12 months despite treatment. Demographics, disease characteristics, and healthcare resource use in the previous 12 months were collected from medical records. Patient‐reported data on urticaria and angioedema symptoms, HRQoL, and work productivity and activity impairment were collected from a survey and a diary.

Results

Almost 50% of patients had moderate‐to‐severe disease activity as reported by Urticaria Activity Score. Mean (SD) Dermatology Life Quality Index and Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire scores were 9.1 (6.62) and 33.6 (20.99), respectively. Chronic spontaneous urticaria markedly interfered with sleep and daily activities. Angioedema in the previous 12 months was reported by 66% of enrolled patients and significantly affected HRQoL. More than 20% of patients reported ≥1 hour per week of missed work; productivity impairment was 27%. These effects increased with increasing disease activity. Significant healthcare resources and costs were incurred to treat CSU.

Conclusions

Chronic spontaneous urticaria has considerable humanistic and economic impacts. Patients with greater disease activity and with angioedema experience greater HRQoL impairments.

Keywords: angioedema, economic burden, observational study, quality of life, urticaria

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) (also called chronic idiopathic urticaria)1 is characterized by the occurrence of urticaria for 6 weeks or longer without identifiable specific triggers.2 The average duration of CSU is frequently reported as 5 years3, 4, 5 but may be longer in more severe cases3, 4—specifically, in patients with concurrent angioedema,4, 6, 7 CSU in combination with inducible urticaria,4, 7 or a positive autologous serum skin test.1, 8 The estimated point prevalence of CSU is approximately 0.5% to 1%.9 Until omalizumab was approved in early 2014, H1‐antihistamines were the only approved medication for CSU and were the mainstay of symptomatic treatment. However, over 60% of patients remain symptomatic despite treatment with second‐generation H1‐antihistamines at the licensed dose.10

Available evidence indicates that all forms of chronic urticaria can substantially affect patients’ quality of life (QoL), ability to perform daily tasks, and mental health.11, 12, 13, 14 Patients with chronic urticaria (used as a proxy for CSU) experience substantial health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and productivity impairments and increased psychological comorbidities relative to patients without chronic urticaria.15, 16, 17 Nevertheless, real‐world research quantifying the humanistic and economic impact of diagnosed CSU is limited, and a number of unmet needs exist in this patient population,9 particularly among those refractory to standard treatment.

The ASSURE‐CSU (ASSessment of the Economic and Humanistic Burden of Chronic Spontaneous/Idiopathic URticaria patiEnts) study sought to improve understanding of CSU and to explore the unmet needs of patients whose disease has persisted for longer than 12 months and is inadequately controlled by standard treatment. Specifically, the main objectives of this study were to characterize, in this population, disease duration, disease activity, and treatment history, as well as to identify and quantify the humanistic, societal, and economic burden of CSU.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

The study design has previously been described in detail.18 Briefly, this noninterventional, multinational, and multicenter study was conducted in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (UK). Recruitment of 700 patients was planned. Data collection occurred from October 2013 until May 2015, with each center recruiting over a 4‐month period. Figure S1 describes the patient selection process. Eligible patients were adults with a clinician‐confirmed diagnosis of CSU19 who had received at least one treatment course with an H1‐antihistamine and were symptomatic despite treatment.18

The study was reviewed and exempted by the RTI International Institutional Review Board and was reviewed and approved by the relevant national, local, and site‐level ethics committees. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki;20 all patients provided written informed consent.

2.2. Study measures

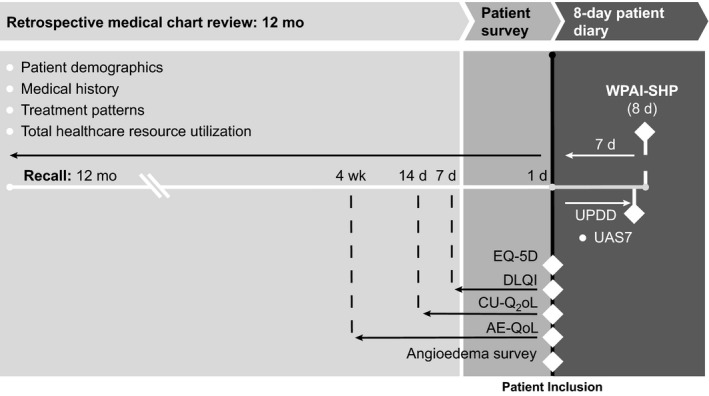

The study included a 12‐month retrospective medical record abstraction, a cross‐sectional patient survey administered at enrollment, and a patient diary completed over an 8‐day period after recruitment (Figure 1). Both the survey21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and the patient diary26, 27, 28 included study‐specific questions and validated PRO measures (Table S1 in Appendix S1).

Figure 1.

Study measures. AE‐QoL=Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire; CU‐Q2oL=Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire; d=days; DLQI=Dermatology Life Quality Index; UAS7=Urticaria Activity Score over 7 days, twice‐daily assessment; UPDD=Urticaria Patient Daily Diary; WPAI‐SHP=Work Productivity and Activity Impairment‐Specific Health Problem

Direct and indirect costs were estimated for each country. Direct costs included CSU‐related treatments, physician visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations documented in medical records, as well as CSU‐related alternative medicine, other out‐of‐pocket costs, and transportation reported in the patient survey. Indirect costs included the cost of patient‐reported workdays missed and lost productivity due to CSU.

2.3. Data analysis

Data analyses were descriptive. Data from all countries were pooled for all outcomes except for direct and indirect costs. With the exception of imputation of missing start dates for therapy data, no imputation of missing data was performed, and no formal hypothesis testing was conducted. Descriptive tables were generated overall and stratified by Urticaria Activity Score over 7 days, twice‐daily assessment (UAS7) score bands. These score bands categorize the UAS7 into four levels of disease activity: UAS7=0‐6 (urticaria‐free or well‐controlled urticaria activity), 7‐15 (mild activity), 16‐27 (moderate activity), and 28‐42 (severe activity).29, 30 Mean values, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and ranges were computed for continuous variables; counts were collected and percentages were computed for categorical variables. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 or later (Cary, North Carolina, USA: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2011).

For the direct cost calculations, costing algorithms were used to assign 2014 unit costs from published sources in the respective country's currency to the resource utilization data.31 Indirect costs for workdays missed and lost productivity due to CSU were calculated by the human capital approach using each country's specific average wage and hours worked.32 Pooled cost calculations were not conducted. Country costs were converted to purchasing power parity dollars (PPP$) using published methodology and sources.33 All cost calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient population

A total of 673 patients were enrolled in 64 recruiting centers, primarily hospital‐based specialist centers (Table S2 in Appendix S2). Most enrolled patients were female (72.7%) and Caucasian/white (90.4%), with a mean (SD) age of 48.8 (15.47) years (Table1). The mean (SD) duration of disease from symptom onset to diagnosis was 24.0 (63.36) months (median 4.7 months) and from diagnosis to the time of study enrollment was 57.7 (77.79) months (median 27.7 months). At diagnosis, 11.2% of patients were assessed by their physician as having mild CSU, 31.4% as moderate, and 36.5% as severe; severity at diagnosis was not available for 21.0% of patients (Table S3 in Appendix S3). Most physicians reported using a combination of factors to assess CSU severity, including number, duration, and intensity of flares (58.5%) and impact on QoL (38.0%); some reported using validated PRO measures, including the UAS7 (15.9%). Allergic rhinitis (16.5%), personal history or family history of allergic disease (14.0% and 14.1%, respectively), and asthma (11.3%) were the most frequently reported additional conditions present at enrollment; concomitant autoimmune diseases, including Hashimoto's, were not uncommon (Table1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient characteristic | Total (N=673) |

|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 48.8 (15.47) |

| Median (range) | 48.0 (19.0‐89.0) |

| Age at symptom onset (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 42.3 (16.54) |

| Median (range) | 42.0 (7.0‐88.0) |

| Age at diagnosis (y) | |

| Mean (SD) | 44.2 (15.92) |

| Median (range) | 44.0 (10.0‐88.0) |

| Disease duration from symptom onset to diagnosis (mo) | |

| Mean (SD) | 24.0 (63.36) |

| Median | 4.7 |

| Disease duration from diagnosis to study enrollment (mo) | |

| Mean (SD) | 57.7 (77.79) |

| Median | 27.7 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 489 (72.7%) |

| Race and ethnicity (n=571) | |

| Caucasian/white | 516 (90.4%) |

| Asian | 15 (2.6%) |

| Hispanic | 10 (1.8%) |

| Other | 20 (3.5%) |

| Data not available | 10 (1.8%) |

| Concomitant diagnoses at enrollment | |

| Autoimmune diseases | |

| Lupus | 2 (0.3%) |

| Hashimoto's | 45 (6.7%) |

| Vitiligo | 3 (0.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (1.8%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 (0.6%) |

| Other autoimmune disease | 35 (5.2%) |

| Connective tissue disease(s) | 6 (0.9%) |

| Myeloproliferative disease | 1 (0.1%) |

| Asthma | 76 (11.3%) |

| Atopic eczema | 21 (3.1%) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 111 (16.5%) |

| History of allergic disease | 94 (14.0%) |

| Family history of allergic disease | 95 (14.1%) |

| Other | 68 (10.1%) |

| Diagnostic testing to exclude trigger factors (n=671) | |

| Yes | 504 (75.1%) |

| No | 137 (20.4%) |

| Data not available | 30 (4.5%) |

SD=standard deviation.

Other includes individuals of Black, Turkish, Arabic, and other ethnic backgrounds, as well as individuals of mixed ethnic background.

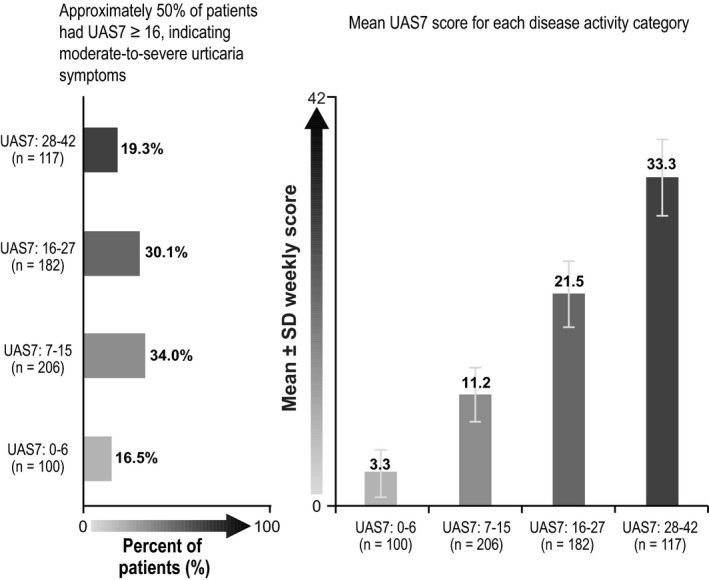

3.2. Urticaria activity

The overall mean (SD) UAS7 score was 17.3 (10.49), suggesting moderate patient‐reported disease activity over 7 days despite treatment. Of the 605 people for whom a UAS7 score could be calculated, 299 (49.4%) had moderate‐to‐severe activity despite treatment, with mean (SD) UAS7 scores of 21.5 (3.39) in the moderate and 33.3 (3.93) in the severe activity groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Urticaria Activity Score over 7 d (UAS7). SD=standard deviation; UAS7=Urticaria Activity Score over 7 d, twice‐daily assessment. Note: UAS7 scores were assessed by summing the average of twice‐daily assessments of hive count and itch score and summing these daily scores over 7 d

3.3. CSU has a major impact on HRQoL, sleep, and daily life

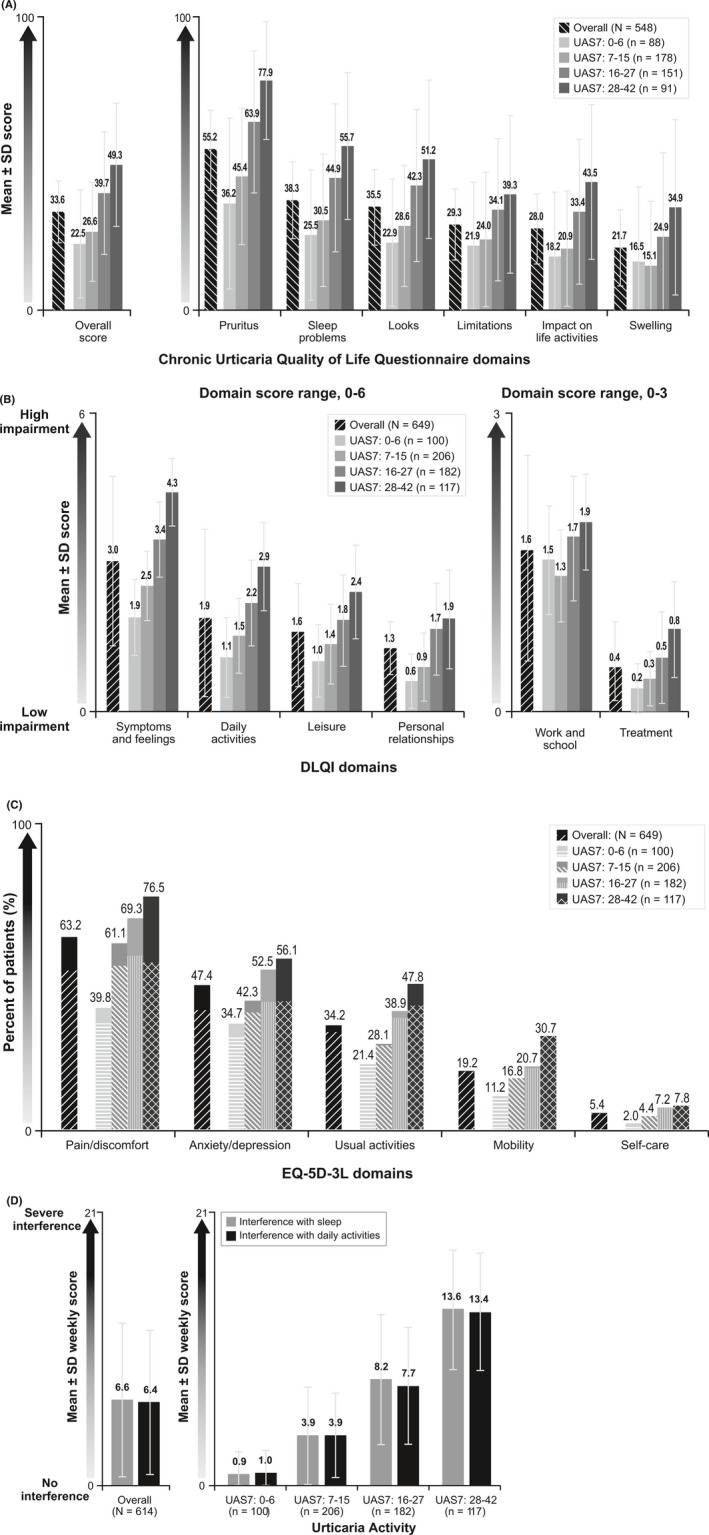

Mean (SD) total scores for the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU‐Q2oL) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) were 33.6 (20.99) and 9.1 (6.62), respectively; 41.6% of patients had a mean DLQI score of 10 or above. The mean (SD) utility score estimate based on the generic EQ‐5D‐3L index was 0.714 (0.2907).

Overall, the most affected aspects of HRQoL were physical symptoms/discomfort, emotional well‐being, interference with daily activities, sleep, and work performance (Figure 3). The most affected domains of the CU‐Q2oL23 were pruritus (mean [SD] score, 55.2 [27.88]), sleep problems (38.3 [25.69]), and looks (35.5 [25.34]) (Figure 3A). Among the six DLQI domains, negative impact was greatest on symptoms and feelings and daily activities (3.0 [1.63] and 1.9 [1.72], respectively, of a maximum possible domain score of 6) and work and school (1.6 [0.97] of a maximum possible domain score of 3) (Figure 3B). The EQ‐5D‐3L domains for which patients most frequently reported moderate or extreme problems were pain/discomfort (63.2% of patients), anxiety/depression (47.4%), and usual activities (34.2%) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Impact of CSU on HRQoL, sleep, and daily life. (A). CU‐Q2oL total and domain scores, overall and by disease activitya,b. (B). DLQI domain scores, overall and by disease activityc. (C). Moderate and extreme problems on EQ‐5D‐3L domains, overall and by disease activityc,d. (D). Interference with sleep and interference with daily activities, overall and by disease activityc,e. CSU=chronic spontaneous urticaria; CU‐Q2oL=Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire; DLQI=Dermatology Life Quality Index; SD=standard deviation; UAS7=Urticaria Activity Score over 7 d, twice‐daily assessment. a CU‐Q2oL results exclude Germany, where the domains differ. Results for Germany can be found in Table S4 in Appendix S4. bNs in legend represents the total number of survey completers in each UAS7 score band. Some of these patients had insufficient data to calculate an overall score and/or individual domain scores. cNs in legends represents the total number of survey completers in each UAS7 score band. Some of these patients had insufficient data to calculate domain scores. dPatterned bars indicate the percentage of patients overall or in each score band with moderate problems, and solid bars indicate the percentage of patients overall in each score band with extreme problems. eWeekly score is calculated as the sum of daily sleep or daily interference scores (range of 0 [no interference] to 3 [substantial interference]), divided by the number of nonmissing daily scores, multiplied by 7

Chronic spontaneous urticaria also had an impact on sleep and daily activities, as shown by weekly mean (SD) scores on the interference with sleep (6.6 [5.93]) and interference with daily activities (6.4 [5.55]) domains of the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary (UPDD) (Figure 3D). The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) results substantiated these findings: One‐third of patients reported considerable impairments (mean [SD] 32.8% [28.96%]) in daily nonwork activities.

Across nearly all HRQoL domains, impact increased with increasing CSU activity.

3.4. CSU‐associated angioedema is a common and debilitating problem

According to medical records, 58.5% (394 of 673) patients were reported to have had CSU‐associated angioedema, and 41.0% (276 of 673) had experienced CSU‐associated angioedema within the past 12 months from inclusion. According to the patient survey, 65.8% of patients (427 of 649) reported experiencing angioedema during the previous 12 months; of these, 75.2% (321 of 427) reported having experienced angioedema within the past 4 weeks. Patients with angioedema reported on a scale of 0‐10 the amount of itching (mean [SD] 7.2 [2.16]), swelling (7.3 [2.73]), and pain (5.4 [3.39]) they experienced during a typical episode over the past 12 months. When asked what they would typically do when they experienced angioedema, 21.5% of patients reported that they would go to the ED for treatment, 12.9% would take an over‐the‐counter medication, and 19.9% would do nothing. During the 7‐day UPDD period, 47.9% of patients (294 of 614) reported at least 1 day of angioedema. Occurrence of angioedema increased with disease activity, as more than two‐thirds of patients (70.1%) in the UAS7 28‐42 band reported experiencing angioedema on at least 1 of 7 consecutive days. The mean (SD) number of days with angioedema ranged from 2.3 (1.60) among patients in the UAS7 0‐6 band to 4.1 (2.18) days among patients in the UAS7 28‐42 band.

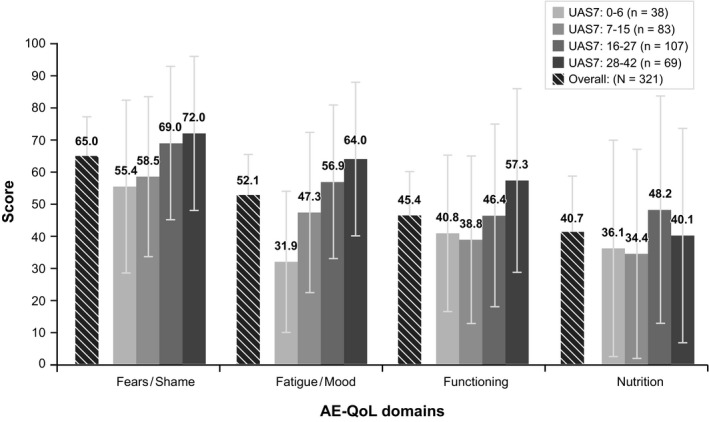

Angioedema significantly affected HRQoL, particularly emotional well‐being. Mean (SD) Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE‐QoL) scores were 65.0 (25.14) on the fears/shame domain and 52.1 (25.83) on the fatigue/mood domain among all patients experiencing angioedema; patients with greater CSU activity reported more significant impacts on these domains (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

AE‐QoL domain scores, overall and by disease activity. AE‐QoL=Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire; UAS7=Urticaria Activity Score over 7 d, twice‐daily assessment. Ns in legend represents the total number of patients in each UAS7 score band who reported angioedema over the past 4 wk in the patient survey. Some patients had insufficient data to calculate one or more AE‐QoL domain scores

3.5. CSU affects work performance and productivity

Of the 604 patients reporting, 341 (56.5%) indicated that they were currently employed. Among employed patients, the mean (SD) absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment were 6.1% (17.83%), 25.2% (25.78%), and 26.9% (27.53%), respectively, over the previous 7 days. Among the 329 employed patients responding, 72 (21.9%) had missed at least 1 hour of work in the past 7 days because of problems associated with CSU; among these, 45 patients (62.5%) missed up to 1 day of work and 27 (37.5%) missed more than 1 day in the past 7 days. The main reasons affecting capacity to work were itching (39.8%) and angioedema (28.2%).

Disease activity affected work performance, and greater disease activity had a greater negative productivity impact: mean (SD) overall work productivity loss was 11.9% (21.55%) among those with lowest disease activity and 43.6% (28.38%) among those with highest disease activity. Presenteeism (ie, impairment while at work) was the primary driver for overall work productivity loss, ranging from a mean (SD) of 9.8% (15.94%) among those with lowest disease activity to 40.4% (27.42%) among those with highest disease activity (Figure S2 in Appendix S2).

3.6. Treatment of inadequately controlled CSU is frequently inconsistent with guideline recommendations

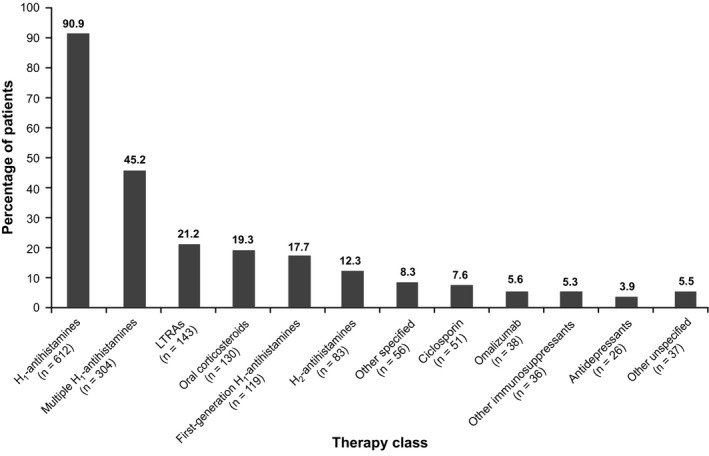

In the preceding 12 months, 90.9% of patients received at least one‐second‐generation H1‐antihistamine (Figure 5), and 45.2% of patients received updosing of H1‐antihistamines, or combinations of H1‐antihistamines plus leukotriene receptor antagonists (6.7%), or H2‐antihistamines (1.3%) or ciclosporin (1.2%), but remained symptomatic. Contrary to clinical guidelines,34 17.7% of patients received first‐generation H1‐antihistamines, and 19.3% of patients received oral corticosteroids for a mean (SD) duration of treatment of 153.2 (127.77) days (median, 118.0; range, 1.0‐366.0 days). Nearly one in five patients (18.1%) were not taking any therapy at enrollment.

Figure 5.

Therapies used in the past 12 mo (N=673). LTRA=leukotriene receptor antagonists. Other immunosuppressants included methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil; other specified therapies included intravenous immunoglobulin, narrowband ultraviolet B procedure, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, levamisole, mesalazine, sulfasalazine, nifedipine, stanozolol, and warfarin. Multiple H1‐antihistamines included combinations of second‐ and/or third‐generation H1‐antihistamine therapies, as well as patients who have multiple records of the same H1‐antihistamine

3.7. CSU has a considerable impact on healthcare resources

Overall, 72.1% of patients had at least one visit to a healthcare professional for their CSU recorded in their medical record in the previous 12 months, with a mean (SD) of 3.3 (3.03) visits. According to medical records, consultant allergists (39.0%) and dermatologists (38.5%) were the most common specialists visited in the 12 months prior to enrollment. Among the 97 patients (14.4%) with at least one CSU‐related ED visit in the past 12 months, the annual mean (SD) number of visits was 1.8 (1.26). Hospitalization for CSU was recorded for 55 patients (8.2%), with a mean (SD) length of stay per hospitalization of 3.7 (2.67) days; 53.8% of hospital admissions were due to nonspecified diagnostic testing, 17.3% were due to angioedema, and the remaining admissions were for other unspecified reasons. Based on patients’ survey responses, in the prior 3 months, patients most frequently visited a family doctor (44.8%) a mean (SD) of 2.7 (3.02) times (among patients with such a visit); 37.4% reported seeing a dermatologist a mean (SD) of 2.5 (2.55) times (among patients with such a visit).

3.8. CSU is costly for society

Total average (SD) annual direct costs per patient per year, as captured in the retrospective medical record review, ranged from PPP$907.1 ($2431.14) in Italy to PPP$2984.2 ($8969.46) in France. The major drivers of these costs were therapies (range, PPP$426.4‐$1788.7) and inpatient visits (range, PPP$250.7‐$1074.4) (Tables S5 and S6 in Appendix S5 and S6).

Average indirect costs, or costs of patient‐reported total work productivity loss over 4 weeks, were driven primarily by the cost of presenteeism (range, PPP$544.5‐$1180.0); the mean (SD) cost of work productivity loss ranged from PPP$544.8 ($603.22) in France to PPP$1287.4 ($1123.80) in Germany (Table S7 in Appendix S7).

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the ASSURE‐CSU study is the first international analysis of the burden of CSU inadequately controlled by standard treatment. We report novel findings for current treatment patterns, impact on HRQoL, and the economic burden to patients, healthcare systems, and society. A key strength is the use of a patient survey and retrospective medical record review to provide more comprehensive evidence than is captured using only administrative data sources (e.g., medical claims). As both disease activity and HRQoL were evaluated over a similar period, the impact of varying levels of disease activity on patients’ lives was clarified. Moreover, we identified significant humanistic and economic burdens relating to CSU that have not been reported previously. Nevertheless, estimates of disease burden from this study may be conservative, and the observed treatment patterns might not represent the general CSU population. Patients were recruited from urticaria specialty centers and, as such, were receiving expert care for CSU.

Most patients in ASSURE‐CSU had moderate‐to‐severe physician‐assessed disease activity at diagnosis, and patients experienced a mean delay of 24 months (and a median delay of nearly 5 months) from symptom onset to diagnosis; mean duration from diagnosis to enrollment was nearly 5 years. Most patients continued to have moderate‐to‐severe disease activity (ie, moderate‐to‐severe itch and hives at least 4 days a week) while completing the patient diary. However, treatment could be suboptimal and in fact was absent for some patients during the study period. Patients not receiving treatment may have discontinued previous treatments owing to ineffectiveness or cost factors, among other reasons.

Angioedema was found to be more frequent than previously thought: Physicians reported that nearly 60% of patients with CSU experienced angioedema, and two‐thirds of them had experienced it within the past 12 months. More patients than physicians reported angioedema during this time period and reported its considerable impact on emotional well‐being, fatigue, and mood. Our findings suggest that angioedema plays a significant role in the burden of CSU, affecting every aspect of HRQoL and driving direct costs. Further analyses of ASSURE‐CSU data are ongoing to examine the misalignment between physicians’ and patients’ reports and to better understand the impact of angioedema.

Mean DLQI scores in this study suggest that CSU has a moderate impact on patients’ HRQoL,35 which is greater than previously thought; further, more than 40% had DLQI scores of 10 or greater, which, in psoriasis, justifies the initiation of a biologic.36 In addition, HRQoL impairments correlated with disease activity, notably so in daily activity and sleep interference domains across measures. Particularly in patients with a UAS7 of 16 or greater, overall impact of CSU on usual activities represents a significant burden to themselves and to society.

Some notable differences were observed between patient and physician reporting, potentially suggesting that patients may not always communicate their urticaria symptoms to their physicians, in turn mitigating physicians’ ability to treat effectively. Unanswered questions remain about patients’ abilities to accurately identify or recall angioedema symptoms and physicians’ likelihood of capturing these events in medical records. Discrepancies also existed between physicians’ and patients’ reports of resources used—specifically visits to other healthcare professionals and medications, particularly alternative therapies (eg, homeopathic treatments), that the patient was using. More research is needed to fully address these differences and provide education and resources to patients and providers alike.

ASSessment of the Economic and Humanistic Burden of Chronic Spontaneous/Idiopathic URticaria patiEnts provides valuable insight into the economic burden of CSU. To our knowledge, only a US claims database analysis,37 a small US single‐center analysis,38 and a cost‐effectiveness analysis in France39 have previously evaluated CSU‐associated costs, and none is directly comparable with our study. Although previously thought to be infrequent, CSU‐related ED visits in ASSURE‐CSU were reported for 14% of patients, and hospitalizations were reported for 8% of patients. This is in contrast to Broder and colleagues’37 findings in the United States that 2% of patients with CSU (of any severity) had CSU‐related ED visits and 0.1% of patients were hospitalized. Differences in national healthcare systems and in CSU severity among the study populations may contribute to the discrepancy in hospitalization patterns. However, Broder and colleagues found a similar number of annual office visits for CSU (3.4 vs 3.3 in ASSURE‐CSU). Moreover, in ASSURE‐CSU, CSU‐related out‐of‐pocket expenses to patients averaged nearly PPP$500 per year and approached PPP$1000 in Canada. As patients in our study were still symptomatic despite treatment, many sought alternative medical therapies, which are generally not covered by country health insurances. In addition, CSU considerably affected productivity, such that one in five patients took time off from work and one in four experienced reduced productivity at work. These findings are comparable with work productivity impairments in chronic urticaria15, 16, 17 and in other dermatologic conditions, including atopic dermatitis,40, 41 plaque psoriasis,42 and severe psoriasis.16, 43, 44

The reasons for ED visits and hospitalizations may center on patient and physician awareness and education. Depending on the healthcare system in a country, the use of this high‐cost care could be due to an inaccessibility of primary‐ or secondary‐care physicians for flare‐ups and steroid prescriptions. Alternatively, patients who have been treated in the ED before may feel that it is where CSU should be treated, or they may receive secondary gain from this visit, such as sick leave. In certain circumstances, hospitalization may be used for observation or to manage angioedema when anaphylaxis is feared by inexperienced ED physicians or because of delays in specialist referral.

Treatment modalities reported included therapies recommended in the current guidelines during the study period. However, patients were not always treated along formal guideline recommendations: For example, sedating first‐generation H1‐antihistamines, intravenous immunoglobulin, and long‐term oral corticosteroids were not uncommon. These results suggest that, at the time of study, some providers may have had insufficient resources or knowledge in treating patients with CSU. They may have resorted to trial‐and‐error approaches with therapies that carry significant side‐effect risks and lack efficacy evidence,2 particularly when treating patients refractory to standard licensed therapy. Moreover, the monoclonal antibody omalizumab was included in the urticaria treatment guidelines in 20132 and was approved for inadequately controlled CSU in 2014. However, omalizumab had not yet launched in the study countries during data collection, and few patients (<6%) in this study were treated with it. Future research should explore how disease burden and outcomes in CSU are affected by the introduction of omalizumab, its inclusion in the clinical guidelines, and its uptake in clinical practice.

While the study used a systematic patient selection method, a similar approach was not possible for physician and center selection due to the small number of specialist units for this population. Centers were selected to achieve variation in location, specialty, size, and type, but the resulting sample is not guaranteed to be representative of all centers and physicians treating patients with CSU. Likewise, inclusion criteria required patients to be symptomatic despite treatment and thus, the study does not reflect the entire population of patients with CSU.

Data and information about symptoms, HRQoL, and out‐of‐pocket expenses collected in the patient survey may have been subject to recall bias. The recall period for validated PROs varied from 7 days for the DLQI to 4 weeks for the AE‐QoL and for the patient medical resource survey was limited to 3 months to minimize the potential for such bias. While there was some heterogeneity across countries, results were strikingly similar particularly with respect to HRQoL.

Additional research is needed to explore patient characteristics, given that most patients in ASSURE‐CSU were Caucasian and (consistent with previous findings45, 46) female, as well as patterns relating to disease activity and duration of disease. Because of the inherent fluctuations in CSU activity, longer or repeated assessments would help confirm the results. The impact of CSU on work performance and productivity warrants additional evaluation. Our findings suggest that there may be inadequate knowledge among medical staff of the appropriate workup for CSU, and there is a need to increase awareness of the economic and humanistic impact of CSU among primary‐ and secondary‐care providers and society in general.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Chronic spontaneous urticaria is a chronic, disabling disease with little previous research that is challenging to treat adequately. The humanistic and economic burden of CSU has been underestimated. There is considerable delay in diagnosis and specialist referral, and there is inadequate knowledge among medical staff in primary and secondary care about CSU. Incorrect treatment patterns have been identified, and the high cost of unnecessary investigations and treatments is due to poor compliance with guidelines and best practices. Additional analyses should explore these findings in detail. To address unmet needs in CSU, it will be important to promote treatment guidelines and evidence‐based practices among healthcare providers.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

This research was performed under a research contract between RTI Health Solutions and Novartis Pharma AG and was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. K.H., D.McB., C.S., and D.W. are employees of RTI Health Solutions, which provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, governmental, and nongovernment organizations. In their salaried positions, they work with a variety of companies and organizations. They receive no payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. C.P. was an employee of RTI Health Solutions when this research was conducted. M.M.B. is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. H.T. is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M.B., K.H., and D.McB. initiated the study. M.M.B., K.H., D.McB, C.S., and D.W. designed the study; M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., M.M., A.N., J.O.d.F., G.S., and K.W. provided clinical input to the study design. K.H., D.McB., C.P., C.S., and D.W. managed data collection, and M.M.B., K.H., D.McB., C.P., C.S., H.T., and D.W. led the data analyses. M.M.B., M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., K.H., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., M.M., D.McB., A.N., J.O.d.F., C.P., G.S., C.S., H.T., K.W., and D.W. interpreted the data. M.M.B., K.H., M.M., and D.McB. drafted the manuscript, and M.A., F.B., W.C., H.O.E., A.G‐A., C.G., A.K., J‐P.L., C.L., A.M., A.N., J.O.d.F., C.P., G.S., C.S., H.T., K.W., and D.W. revised it critically for intellectual content. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for the work as a whole.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following recruiting physicians: Drs. Sameh Hanna, Jacques Hebert, Amin Kanani, Paul Keith, Gina Lacuesta, Jason Lee, G‐Daniel Schachter, Susan Waserman, and Shahin Zanganeh in Canada; Drs. Emmanuelle Amsler‐Soria, Annick Barbaud, Claire Bernier, Laurence Bouillet, Jean‐Jacques Grob, Giordano Labadie, Laurent Machet, Paul Martin, Fabien Pelletier, Nadia Rasion‐Peyron, Delphine Staumont‐Salle, and Manuelle Viguier in France; Drs. Andrea Bauer, Randolf Brehler, Hans Merk, Franziska Rueff, Petra Staubach‐Renz, and Amir Yazdi in Germany; Drs. Ornella de Pità, Silvia Mariel Ferrucci, Maria Laura Flori, Giampiero Girolomoni, Giovanni Pellacani, Paolo Pigatto, and Domenico Schiavino in Italy; Drs. Menno T. W. Gaastra, G. R. R. Kuiters, M. L. A. Schuttelaar, R. A. Tupker, Thomas Rustemeyer, Phyllis Spuls, and Roy Gerth van Wijk in the Netherlands; Drs. Jesús Borbujo, Pablo de la Cueva, Alejandro Joral Badas, Moisés Labrador Hornillo, Ana Perez Montero, Javier Pedraz, and Esther Serra in Spain; and Drs. Anthony Bewley, Seautak Cheung, Nyz Chiang, Venkata Gudi, Frances Humphreys, Dimtra Koumaki, John Reed, and Donna Torley in the United Kingdom. Kate Lothman of RTI Health Solutions provided medical writing services, which were funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Maurer M, Abuzakouk M, Bérard F, et al. The burden of chronic spontaneous urticaria is substantial: Real‐world evidence from ASSURE‐CSU. Allergy. 2017;72:2005–2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13209

Funding information

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Christina Proctor, MStat, was affiliated with RTI Health Solutions at the time that this research was conducted.

Edited by: Werner Aberer

REFERENCES

- 1. Maurer M, Bindslev‐Jensen C, Gimenez‐Arnau A, et al. Chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) is no longer idiopathic: time for an update!. Brit J Dermatol. 2013;168:455‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, et al. The EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update. Allergy. 2014;69:868‐887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toubi E, Kessel A, Avshovich N, et al. Clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting chronic urticaria duration: a prospective study of 139 patients. Allergy. 2004;59:869‐873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Valk P, Moret G, Kiemeney L. The natural history of chronic urticaria and angioedema in patients visiting a tertiary referral centre. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:110‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaig P, Olona M, Muñoz Lejarazu D, et al. Epidemiology of urticaria in Spain. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14:214‐220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beltrani VS. An overview of chronic urticaria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002;23:147‐169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sánchez‐Borges M, Caballero‐Fonseca F, Capriles‐Hulett A, González‐Aveledo L, Maurer M. Factors linked to disease severity and time to remission in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:964‐971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Thumpimukvatana N, Pinkaew S. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: prevalence and clinical course. J Dermatol. 2007;34:294‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev‐Jensen C, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a GA²LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guillén‐Aguinaga S, Jáuregui Presa I, Aguinaga‐Ontoso E, Guillén‐Grima F, Ferrer M. Up‐dosing non‐sedating antihistamines in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1153‐1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reeves GE, Boyle MJ, Bonfield J, Dobson P, Loewenthal M. Impact of hydroxychloroquine therapy on chronic urticaria: chronic autoimmune urticaria study and evaluation. Intern Med J. 2004;34:182‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maurer M, Magerl M, Metz M, Zuberbier T. Revisions to the international guidelines on the diagnosis and therapy of chronic urticaria. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:971‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Donnell BF, Lawlor F, Simpson J, Morgan M, Greaves MW. The impact of chronic urticaria on the quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:197‐201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kang MJ, Kim HS, Kim HO, Park YM. The impact of chronic idiopathic urticaria on quality of life in Korean patients. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:226‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balp MM, Vietri J, Tian H, Isherwood G. The impact of chronic urticaria from the patient's perspective: a survey in five European countries. Patient. 2015;8:551‐558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mendelson MH, Bernstein JA, Gabriel S, et al. Patient‐reported impact of chronic urticaria compared with psoriasis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;28:229‐236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vietri J, Turner SJ, Tian H, Isherwood G, Balp MM, Gabriel S. Effect of chronic urticaria on US patients: analysis of the National Health and Wellness Survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;115:306‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weller K, Maurer M, Grattan C, et al. ASSURE‐CSU: a real‐world study of burden of disease in patients with symptomatic chronic spontaneous urticaria. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev‐Jensen C, et al. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417‐1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Medical Association . Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. October 2008. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf. Accessed April 16, 2016.

- 21. EuroQol Group . EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baiardini I, Pasquali M, Braido F, et al. A new tool to evaluate the impact of chronic urticaria on quality of life: chronic urticaria quality of life questionnaire (CU‐Q2oL). Allergy. 2005;60:1073‐1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Młynek A, Magerl M, Hanna M, et al. The German version of the Chronic Urticaria Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire: factor analysis, validation, and initial clinical findings. Allergy. 2009;64:927‐936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67:1289‐1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flood EM, Zazzali JL, Devlen J. Demonstrating measurement equivalence of the electronic and paper formats of the Urticaria Patient Daily Diary in patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Patient. 2013;6:225‐231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mathias SD, Dreskin SC, Kaplan A, Saini SS, Spector S, Rosén KE. Development of a daily diary for patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:142‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reilly M . Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire. 2004. Available at: http://www.reillyassociates.net/Index.html. Accessed December 2013.

- 29. Stull D, McBride D, Tian H, et al. Analysis of disease activity categories in chronic spontaneous/idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2017; 177:1093‐1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khalil S, McBride D, Gimenez‐Arnau A, Grattan C, Balp M‐M, Stull DE. Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in validation of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU/CIU) health states. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:AB131. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hay JW, Smeeding J, Carroll NV, et al. Good research practices for measuring drug costs in cost effectiveness analyses: issues and recommendations: the ISPOR Drug Cost Task Force Report—Part I. Value Health. 2010;13:3‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liljas B. How to calculate indirect costs in economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(1 Pt 1):1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) . PPPs and exchange rates 2014. Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE4. Accessed December 21, 2015.

- 34. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev‐Jensen C, et al. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1427‐1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659‐664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finlay AY. Current severe psoriasis and the rule of tens. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:861‐867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Broder MS, Raimundo K, Antonova E, Chang E. Resource use and costs in an insured population of patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:313‐321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Delong LK, Culler SD, Saini SS, Beck LA, Chen SC. Annual direct and indirect health care costs of chronic idiopathic urticaria: a cost analysis of 50 nonimmunosuppressed patients. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:35‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kapp A, Demarteau N. Cost effectiveness of levocetirizine in chronic idiopathic urticaria: a pooled analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Whiteley J, Emir B, Seitzman R, Makinson G. The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: results from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2016.1195733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yano C, Saeki H, Ishiji T, et al. Impact of disease severity on work productivity and activity impairment in Japanese patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:736‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schaefer CP, Cappelleri JC, Cheng R, et al. Health care resource use, productivity, and costs among patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:585‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, Roberts J. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:514‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kruntorádová K, Klimeš J, Šedová L, Štolfa J, Doležal T, Petříková A. Work productivity and costs related to patients with ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;4:100‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ferrer M. Epidemiology, healthcare, resources, use and clinical features of different types of urticaria. Alergológica 2005. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19(Suppl 2):21‐26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maurer M, Staubach P, Raap U, Richter‐Huhn G, Bauer A, et al. H1‐antihistamine‐refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria: it's worse than we thought—first results of the multicenter real‐life AWARE study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47:684‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials