Abstract

Despite three decades of dramatic treatment breakthroughs in antiretroviral regimens, clinical outcomes for people living with HIV vary greatly. The HIV treatment cascade models the stages of care that people living with HIV go through toward the goal of viral suppression and demonstrates that <30% of those living with HIV/AIDS in the United States have met this goal. Although some research has focused on the ways that patient characteristics and patient–provider relationships contribute to clinical adherence and treatment success, few studies to date have examined the ways that contextual factors of care and the healthcare environment contribute to patient outcomes. Here, we present qualitative findings from a mixed-methods study to describe contextual and healthcare environment factors in a Ryan White Part C clinic that are associated with patients' abilities to achieve viral suppression. We propose a modification of Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization, and its more recent adaptation developed by Ulett et al., to describe the ways that clinic, system, and provider factors merge to create a system of care in which more than 86% of the patient population is virally suppressed.

Keywords: : AIDS, HIV, medication adherence, patient care

Introduction

Despite three decades of dramatic treatment breakthroughs in antiretroviral therapy (ART), <30% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the United States are virally suppressed.1 Viral suppression rates are exceptionally low for populations that have not consistently been engaged in care, including vulnerable youth2–4 as well as those who are homeless,5,6 actively use substances,7,8 and have persistent and untreated mental illness.9–11 Ending the AIDS epidemic will require that more people living with HIV are engaged and sustained HIV care.12 To this end, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS has set a 90–90–90 goal, which states that by 2020, 90% of those living with HIV will know their status, 90% of those diagnosed will receive sustained antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of those individuals will be virally suppressed.12

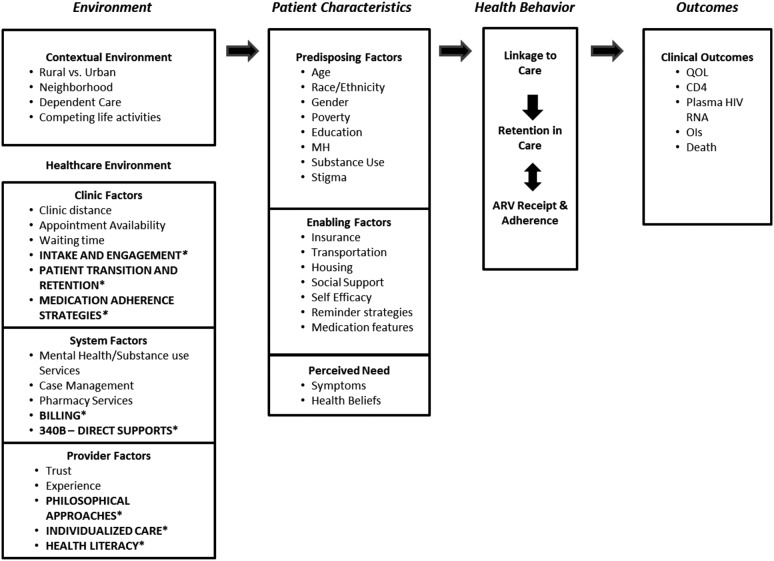

Ulett et al. created an adaptation of Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization13–15 to examine how environmental factors, patient characteristics, and health behaviors combine to produce patient movement along the HIV treatment cascade, the framework that describes the dynamic stages of HIV care (Fig. 1; Ulett et al. model is denoted without asterisks).1,16 In its description of HIV clinical Outcomes, the Ulett model includes Quality of Life, CD4 and HIV Viral Load counts, opportunistic infections, and death. Health Behaviors include Linkage to Care, Retention in Care, and ART Receipt and Adherence. These steps are consistent with the HIV Treatment Cascade,16 which has become the benchmark for conceptualizing the process of improving patient care outcomes. The middle of the Ulett model describes Patient Characteristics, which have been widely examined in previous studies. Race, age, and gender have been associated with differences in HIV outcomes: black and younger PLWHA have lower rates of retention in care, whereas women, blacks, and Latinos have sub-optimal rates of receipt of ART.17 Vulnerable and marginalized populations, such as those who are homeless or unstably housed,6,18–26 men who have sex with men,27 transgender women,28 sex workers,27,29,30 people with substance use disorders,27,31–33 and those who have been incarcerated,34–37 have low rates of treatment success.

FIG. 1.

Adapted model of health services utilization. *Denotes additions to the Ulett/Andersen model. MH, mental health; QOL, quality of life.

Fewer published studies describe distal, environmental factors as they relate to the clinical environment as shown on the left side of the Ulett model. Some studies have examined provider characteristics that are associated with improved patient engagement and retention; however, these findings tend to focus on provider–patient interactions such as communication and patient satisfaction.38–42 Although critical to optimizing patient outcomes, such as antiretroviral (ART) adherence and viral suppression, these dynamics exist within clinical systems of care. There is limited research that describes the systems of care themselves, which are a piece of the patient care puzzle and are likely to contribute to improved patient outcomes, including viral suppression.

From January 2014 to July 2015, we conducted a mixed-methods study at the Allegheny Health Network Positive Health Clinic (PHC), a Ryan White Part C provider located in Pittsburgh, PA. PHC was founded in 1996 by a nurse and a nurse practitioner in response to a growing number of PLWHA in the region of Southwestern Pennsylvania who had unmet needs for clinical care. PHC staff members include nurses, physicians, medical assistants, social workers, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, a peer navigator, pharmacists and a pharmacy technician, and administrative support, including data entry and quality assurance professionals. PHC provides a range of clinical services, including HIV testing and referrals, sexually transmitted infections (STI) screening, and medical treatment for HIV, as well as multiple supportive services, including social work support, mental health therapy, and direct supports such as transportation assistance. In addition, the clinic has a contracted pharmaceutical dispensary on-site, which operates under the 340B funding structure, a federal drug discount program that enables entities to purchase medications at deeply discounted prices. By receiving this discount yet billing for Medicare or privately insured patients at full cost, covered entities can realize residuals that can be spent on comprehensive services to vulnerable patients, which would otherwise not be reimbursable.

Previous analyses of clinical data showed that the majority (86.6%) of PHC patients were virally suppressed at the time of their last visit (<200 copies/mm based on clinic policy and Health Resources and Services Administration standards43) and, among patients taking HIV medicines, 92.6% had good adherence as operationalized by a score of 10 or higher on the Case Adherence Index Questionnaire (range, 3–16).44 Subgroup analyses were consistent with the broader HIV literature in that race, age, and income were associated with both viral suppression and medication adherence: Younger individuals (aged 20–29 years) and individuals with lower incomes (≤$20,000 per year) were less likely to be virally suppressed, and non-white individuals, younger individuals, and individuals with lower incomes were less likely to have good adherence.17 What is striking about PHC, however, is that housing status and substance use were unrelated to viral suppression and medication adherence,45 which is contrary to the extant literature on the HIV cascade.18,19,27,31–33

Given PHC's success in serving vulnerable and marginalized PLWHA, the research team used qualitative methods to describe the contextual and healthcare environment factors that may contribute to PHC patients' abilities to achieve viral suppression. Based on these results, we suggest an adapted model of health services utilization (incorporated in Fig. 1 with changes denoted with asterisks.)

Methods

The aim of the qualitative arm of our study was to explore patients' facilitators and barriers to care, and specifically to discern aspects of the PHC that contribute to patients' clinical success (defined as viral suppression). The study team conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with 17 staff members from the clinic, including nurses, physicians, social workers, a physician assistant, a nurse practitioner, medical assistants, and administrative staff. Interviews were also conducted with 23 patients, purposively sampled to ensure that both virally suppressed and non-virally suppressed patients were included. Patients were recruited to interviews by clinic staff members, primarily social workers, who informed patients of the nature of the study and that interviews were voluntary and confidential. Specifically, patients were informed that the purpose of the study was to explore challenges, barriers, and successes related to linkage to, retention in, and re-engagement in care for patients of the PHC. Patients who completed surveys were provided with $20 gift cards to a local grocery store.

We sought to include diverse perspectives in staff and patient interviews. All staff members were invited to participate in interviews and we ultimately interviewed 17 out of 21 personnel, including nurses, administrators, physicians, a physician assistant, nurse practitioners, medical assistants, social workers, and patient advocates. For patient interviews, we were interested in including patients who were diverse in terms of race, gender, and viral suppression status, knowing that results might be biased if we only interviewed patients who were virally suppressed. We interviewed 6 women and 17 men, 7 Caucasian patients and 16 African American patients, 8 patients who were not virally suppressed, and 15 patients who were virally suppressed. The study team continued to engage patients in qualitative interviews until we perceived that saturation had been achieved. This was assessed by regularly reviewing the emergence of new themes during regular study team meetings.

Staff and patient interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, then analyzed and coded by using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., Version 10). We used a deductive content analysis to understand the extent to which the data supported hypothesized measures of importance46 as well as an inductive analytic approach47,48 to explore emerging themes. First, four members of the interview team listened to the audiotapes and contextualized key themes. Using these themes and our a priori assessment domains, we developed an initial code list and then three members of the team coded one of the transcripts line by line to explore for additional themes and to assess for consistency. New codes and differences in coding strategies were discussed by the team until agreement was reached regarding application of codes. Using a revised codebook, two researchers coded the rest of the interviews. Finally, an axial coding process was used to gain a deeper understanding of how the codes related more broadly to one another.49 Transcripts were then reviewed once more to explore the new coding categories.

Results

Our qualitative data suggested a number of characteristics of the healthcare environment that played important roles in retaining patients in care and helping them to improve their clinical outcomes. We have organized our qualitative findings to describe these important aspects of care in accordance with the Ulett model (for a summary, Table 1; for a visual depiction, Fig. 1, where our findings are denoted with asterisks).

Table 1.

Results from Qualitative Interviews

| Emergent theme | Impact on patient care |

|---|---|

| Clinic factors | |

| Patient intake | First point of contact is with Medical Social Worker. |

| Barriers to care addressed on first point of contact to improve patient access. | |

| Patient centeredness and harm reduction inform first point of contact. | |

| Patient transition and retention | Empanelment—patients assigned to specific clinical provider teams so that they see the same providers each time. |

| Providers prioritize team-based care and within-team communication via early morning huddles and electronic messaging. | |

| Medication adherence strategies | Individualized adherence plans are developed in collaboration with each patient. |

| Creative adherence strategies are used. | |

| System factors | |

| Ancillary services | On-site case management, mental health therapy, and pharmacy services improve patient access to care. |

| Billing/340B covered entity | Funds derived from 340B provide expanded set of services to patients, as these provide a financial buffer for non-billable no-shows and missed appointments. |

| 340B funds also enable the provision of material supports to resolve practice barriers to care. | |

| Provider factors | |

| Philosophical approaches: harm reduction and valuing the patient | Providers strive to help patients move to the next lowest acceptable level of risk. |

| “Universal harm reduction” messages are shared with all patients regardless of patient disclosure of harmful health behaviors. | |

| Patients are valued as “whole people” with a range of experiences that impact health behaviors. | |

| Patients are not judged based on harmful health behaviors. | |

| Individualized care | Care is structured based on each patient's strengths and needs. |

| Health literacy | Efforts to improve patients' levels of health literacy begin at intake and are carried through all clinic interactions. |

| Health literacy emphasizes knowledge of medications, how they work, and the meaning of viral load as well as how it is affected by medication adherence or non-adherence. | |

| A goal of health literacy is to involve patients in treatment decision making. | |

Clinic factors

In the Ulett-adapted Andersen model, clinic factors associated with engagement include clinic distance, appointment availability, and waiting time, suggesting that accessibility of services correlates with patient engagement. Based on our findings, we have expanded this category to include aspects of care that promote or prohibit patient access that are limited to the clinic or practice where care is provided and that describe tangible offerings; that is, do not include qualities of services or descriptors of interactions. In addition, we have expanded the description of Clinic Factors to include other structures of services that were integral to patient engagement, retention, and adherence at PHC; namely, Patient Intake Processes, Patient Scheduling and Transitions, and Medication Adherence Strategies. These themes were common in both patient and provider interviews, emerging in 18 out of 23 patient interviews and 14 out of 17 provider interviews.

Patient intake and engagement

At PHC, the patients' first point of contact is with a social worker. While scheduling intakes, the social worker strives to be patient centered in that they address possible barriers in the patient's schedule or other access issues so that the patient can be brought in as soon as he is available. The clinic shares a waiting room with the Department of Internal Medicine, which helps to reduce stigma that can be associated with visiting a clinic that only provides care to PLWHA. Because PHC also conducts HIV testing, patients who test positive have intakes completed immediately after a positive result is given to improve linkage to care.

Intakes include: a comprehensive assessment of the patient's health history; a “PHC 101” session in which clinic services and processes are introduced to the patient; problem-solving patient-specific barriers to care; medical triage and assessment, in which patients were assessed for acute medical needs; health literacy assessment and education; and information regarding substance use risk, methods to reduce risk, and treatment opportunities regardless of whether or not substance use has been disclosed. This is because patients may not initially feel comfortable disclosing behaviors that have historically been stigmatized and because it is possible that even if patients are not actively using substances at intake, they may engage in those behaviors at future points in time. Providing the patient with information about how to decrease risks associated with substance use includes conversations not only about harm reduction strategies, such as syringe exchange for people who use injection drugs, but also about problem-solving barriers to adherence that may be associated with substance use. For example, providers share information regarding the importance of planning to take anti-retroviral medications even if the patient knows he will be out drinking. This kind of information sends the message that providers at PHC are non-judgmental and respectful of patients. After intake, patients are taken to the hospital laboratory where blood is taken for viral load and CD4 counts, and they are scheduled for an appointment with a medical provider within 2 weeks.

Patient transitions and retention

To improve continuity of care, PHC uses an empanelment approach in which patients are assigned to individual physicians, nurses, and social workers so that they see the same providers each time they come in for care. There is a significant emphasis on team-based care, in which members of the treatment team collectively share information regarding the patient's needs and status. Team communication is facilitated through formal processes such as meetings every morning to discuss that day's patients, known as 8:30 huddles, as well as informal processes. For example, the culture of the clinic is one of low-threshold communication, in which staff members stop each other in the hall or in between patients to ask questions or share updates. Electronic resources are also used consistently to log and receive updates about medical care or other patient issues or needs that may serve as barriers or facilitators to care. Discussions regarding patient transition and retention occurred 36 times in 13 out of 17 interviews with providers. This theme was not coded in patient interviews because it reflects a clinic process that is unlikely to be identifiable by patients.

PHC operates from a care-on-demand approach in that there is no locked door that patients must pass through to enter the main clinic area. Patients can walk into the hall where social workers' offices are located at any time. Although there is a waiting room where medical assistants check in patients who have scheduled medical visits, the hallway where the social workers and patient navigators are located are fully accessible to all patients. This means that patients who have practical, psychosocial, or urgent medical needs can walk in and be seen at any time simply by going to their social workers' offices or by stopping the first staff member they recognize. Although this level of access places a great level of demand on the social work staff, it does create an environment in which patients feel welcomed and valued. Though it might seem that this level of access could create frustration among patients if their visits were interrupted by other patients, this did not emerge as an identified problem in our interviews with staff and patients. Staff navigate patients to other providers via warm handoffs, in that they accompany patients to the next department (as with labs) or the person who will be seeing them. The team also follows patients through transitions of care, as when a patient is hospitalized. Specifically, one of the providers checks every day to see whether patients living with HIV/AIDS have been admitted or have had emergency room visits. When patients are discharged, a PHC team member follows up with the patient within 24 h to make sure they are stabilized and any referrals are completed.

Medication adherence strategies

Medication adherence strategies were a common theme in both staff and patient interviews, noted 381 times by 11 different patients and 114 times by 16 different providers. To address medication adherence, PHC providers develop individualized adherence plans for each patient in which they assess the patient's current status and develop adherence goals, as well as identify barriers to achieving them. This process often includes ad hoc “Meetings for Medications” during which the pharmacist, medical providers, and social workers sit down with the patient to address his specific adherence needs. A number of adherence strategies are used depending on the patient's level of need, including Directly Observed Therapy and pill boxes set up by the pharmacy technicians.

They give me a box. I have my own box of my medication, my insulin, and they draw the insulin up for me and I take it and they make me take my sugar and write it down in the book. They want to make sure I take it, they will call and say “Where you at? Bring your butt in and let's get this done.” (PHC Patient)

PHC staff are creative in the ways that they individualize adherence support. For one new patient, the peer navigator called every day for her first 30 days of care to support her adherence and then congratulated her on “graduating” to independent medication adherence. Any positive change in adherence is celebrated; for example, one social worker stocked a box of toiletries and cosmetics from which one of her patients was able to choose an item when she accomplished a full month of taking her meds. PHC staff provides reminder calls before visits and calls to re-schedule appointments within 24 h of missed visits.

System factors

The Ulett model includes mental health, substance use, and case management services in the category of System Factors. In addition to describing these types of ancillary services, we also include Billing and Reimbursement in this category because of their apparent impact on patient care and clinical outcomes.

Ancillary services

PHC provides case management services through its medical social workers and mental health support through a full-time Licensed Clinical Social Worker as well as through a contracted community psychiatrist. Mental health supports include individual therapy, group therapy, and psychiatric visits and medications. All of these services are provided on site. Another important ancillary service is the on-site dispensary, where patients can obtain their medications and consult with a pharmacist and a pharmacy technician. Staff emphasized this complement of services, which are provided via a team approach to care, as critical to patient success. Non-medical, ancillary services were discussed as facilitators of adherence by 11 different patients and 16 providers.

….there's a psychiatrist that sees patients there and a therapist that sees them. If you think about a wheel, you've got your HIV, your social work, your nurses, your psych—I mean, you're really kind of hitting that 360 degree approach of how people should be cared for. (Physician)

A lot of times that ends up being a little bit of group thing as well, where the social worker is there, the provider is there sometimes in that meeting as well. Where we just say, “You know, we really care about you and that's why we're bringing an entire team into talk to you about this. We'd love to try and figure out something that's going to work for you but we also understand and will support you if you decide not to take medications. But you want to make an informed decision based on all the information we can give you we want you to ask questions if you don't understand the information.” And on a rare occasion, I think that's been the case, where the patient didn't really understand the severity of not taking the medication until they were faced with a room full of people from multidisciplinary teams saying, “Listen, this isn't good, let's figure something out so we can work together and help you.” (Pharmacist)

Billing and 340B funding structure

The billing and reimbursement structures in place at PHC also contribute to patient retention in care, as referenced 46 times by 15 providers. PHC experiences significant prescription drug cost savings through the 340B pharmacy program, which are used to offer an expanded set of services to its patients. Importantly, these funds provide a financial buffer to PHC that enables the clinic to maintain financial stability even though ∼60–70% of patient visits to the care team (including social workers) are non-reimbursable. This funding structure means that providers are not financially affected by no-shows, further supporting the low-threshold approach to approach. It also enables PHC to readily problem-solve practical barriers to care for its patients. For example, patients are given bus tickets when it is determined that transportation is limiting retention.

…if these people are getting bills and so forth they won't come because they're being hounded by somebody… So as much as I can smooth that out, I do. They often call me for questions about, “This shot wasn't covered, what am I going to do?” We're going to pay for it. We'll take care of it. I just try and calm them down because I don't want to give them any excuse to make us part of the problem. (Social Worker)

Provider factors

Provider factors include those having a significant impact on the patient–provider relationship such as trust, provider experience, and concordance, which refers to the degree to which patients perceive themselves to be similar to providers in terms of beliefs, values, and communication.50 In our interviews, four specific aspects of provider factors emerged: harm reduction approaches, health literacy behaviors, valuing the patient, and the provision of individualized care. Though some of these terms reflect concepts and processes that were not meaningful to most patients, harm reduction was referenced 119 times by 17 providers and individualized care was discussed 147 times by 17 providers.

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a term used broadly to refer to interventions that are aimed at helping patients move to the next lowest acceptable level of risk on the path toward optimal health outcomes. Harm reduction recognizes that most individuals engage in multiple behaviors that negatively affect health, and that full elimination of such behaviors is unlikely.51–55 This approach is demonstrated at PHC in several ways and across the spectrum of services. For example, during the patient intake process, providers explicitly share information with patients about reducing risks associated with substance use without assuming that abstinence is the goal. Doctors, pharmacists, social workers, and nursing staff consistently share health risk information while empowering patients to make their own health decisions. Also in keeping with the harm reduction approach, any positive movement toward health goals is celebrated, and backwards movement or lack of movement are not penalized.

A lot of the patients, they come here with drug addictions, and they [the staff] know it, but they still focus on the medical and making sure they're okay, so constantly looking beyond just the addiction or just the hindrance. They're awesome. They work on cutting down the usage of whatever it is that is causing harm. That's harm reduction. That's what I like, and they don't judge. If they do behind closed doors, I don't know, but towards their patients, they don't. (PHC Patient)

Valuing the patient

Rather than simply tolerating patients' harmful health behaviors, PHC values the patient as a whole person who presents with a range of experiences, including trauma, stigma, and marginalization. Providers accept their patients' behaviors as part of the experience of treating them and provide very low-threshold care. As stated by one provider, “Your numbers are bad, but that doesn't mean you're bad.” Staff members are trained that their first answer is never “no” but “yes and assess,” meaning they attempt to meet the patient's need and then assess the possible impact of this action. Patients are seen even if they show up late for appointments, and when patients return to care after dropping out, they are welcomed back.

We treat the person, not the disease. (Social Worker)

It's a privilege to take care of you. (Physician)

Individualized care

PHC providers emphasize structuring care for each patient in a way that is responsive to that individual's strengths and needs. Before developing a treatment plan, PHC providers first “figure out how patients live.” In addition to addressing barriers to care, knowing what is important to patients can be helpful in motivating them toward adherence or other patient-developed goals. Providers talk with patients not only about their HIV status and treatment regimens but also about whatever is important to the patient, including family members, pets, partners, problems, and successes.

At one point, I didn't care about nothing. You know what I mean? They make me care about myself here. That's what I meant to tell you too because for a while, I didn't care… I didn't care about nothing. I didn't care about how I looked or nothing. It seemed like they helped me with all of that. Now I dress good and everything. Everything, for real. I can say they literally brought me up from nothing, for real. (PHC patient)

Health literacy

The health literacy focus begins during intake and carries through all clinic interactions with patients. This theme emerged 83 times among 22 out of 23 patients, and 57 times in 15 out of 23 providers. To improve health literacy among patients, providers constantly assess what patients know about their HIV disease and medications, and work to fill these gaps in knowledge. The theory is that if patients do not understand how medications work, they are unlikely to understand the importance of taking them as prescribed. Information commonly shared by PHC providers during patient visits includes how medications work, what viral load and CD4 counts mean, what happens when medications are not taken consistently, as well as what to expect in terms of side effects and how these can be addressed, including when it is important to call their provider. All patients consistently receive information about interactions between prescribed and illicit drugs and about how to reduce risk when using substances, including alcohol.

An important reason for promoting patients' health literacy is that patients can actively participate in treatment decision making with their providers. Although viral suppression is the goal of the field of HIV care, it is not necessarily the goal of each PLWHA. PHC providers do not automatically assume that all patients should be prescribed ART, but rather help each patient to develop his or her own set of treatment goals. In some cases, PHC providers may suggest delaying ART if the patient is not ready to be adherent with medications.

They told me to take the medicine and I took it for months, at least a good six months, and they couldn't find it in my blood and nobody ever told me that you got take this for the rest of your life…They said, “You have to come back to the clinic and see us.” I said “No. I'm undetectable,” and they said “Okay, you wanna stay like that, right?” I said “Yeah, I haven't been there in a couple months” and they said “B, you have to take this medicine for the rest of your life.” My jaw dropped. I was like “Wow” and here I am. (PHC patient)

I know what each one of those pills are, what they're for… I know that because I'm involved with my treatment, you know? Me and the doctor, we actually sit down and talk about me. I ask questions, you know? I've learned a lot. I mean, I've learned so much, really. (PHC patient)

Discussion

The PHC model of care has produced positive patient outcomes, helping more than 86% of its patients to become virally suppressed. There are many adherence studies that focus on how to improve patient behaviors that affect clinical outcomes and far fewer address structural interventions. We have presented findings regarding the impact of the less-understood healthcare environment on patient outcomes. Some of the approaches described here have been previously associated with patient outcomes, such as the availability of ancillary services, including mental health, substance use, and case management interventions.56–58 However, to our knowledge, this is the first time that the Anderson Model as adapted by Ulett has been described with this level of detail on the healthcare environment and system of care.

Our findings suggest that the 340B funding structure increased the PHC's ability to care for PLWHA. Clinics that depend solely on insurance revenue may not have the ability to continue to see patients who repeatedly miss visits, or the resources necessary to provide social support services that are not traditionally reimbursed. The 340B drug pricing program is not the only payment model or funding structure that can offer clinics the same type of ability to comprehensively meet patient need, but from PHC's perspective, protecting the 340B drug pricing program is a policy issue that will be essential to keeping marginalized populations in care. PHC's use of residuals generated through the drug discount program to provide expanded services to vulnerable patients reflects the original purpose of this federal policy, unlike other hospitals and affiliated clinics that are increasingly using this program to enrich their own settings.59

The provider–patient relationship quickly emerged as a prominent theme in this study. “Being known as a person” is a measure that has been shown to reflect the patient–provider relationship and to be predictive of retention in care,40 and this is clearly demonstrated at PHC. In addition, provider factors that have been linked to patient retention and adherence include trust, experience, communication, and concordance.38,40,60,61 Results from interviews with staff and patients suggest that, at PHC, providers treat their patients warmly and express interest in their personal lives, an approach supported by previous research showing that patients prefer to think of their providers as friends or family members.62 The closeness of the provider–patient relationship as well as the low threshold of care demonstrated by the PHC model may help patients to feel valued and, in turn, may improve their retention in care. However, it must be acknowledged that these clinic characteristics are highly demanding of its staff, especially for social workers since they can be interrupted by patients at any time. This stress created by this level of demand and the concept of self-care were explored in the staff interviews, though no specific or comprehensive solutions emerged for protecting staff members from the stress that is associated with this work.

Further examination of the use of harm reduction techniques in clinical settings is essential to understanding how to optimize quality care. Though most often discussed with reference to interventions with substance users, yet harm reduction has been shown to be effective in working with vulnerable populations affected by other health conditions.63,64 However, although one study has demonstrated the usefulness of a clinic-based harm reduction approach in reducing secondary transmissions,65 there is little, if any extant, research describing how harm reduction is practiced in clinical settings to improve patient outcomes. Our findings suggest that it may be an important tool in helping patients to improve their clinical outcomes, especially those who struggle with retention in care and adherence.

These findings should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, all data were collected in a single HIV clinical setting so results are not generalizable to other clinics or cities. In addition, patients were recruited to qualitative interviews in the clinic setting, which means that the most disengaged patients or those who did not have appointments during the recruitment period were not able to be interviewed. The one-on-one structure of interviews may impose various forms of bias, including moderator acceptance bias, in which interviewees may report information that they think is consistent with the interviewers' expectations, as well as moderator bias, in which actions or expectations of the interviewer affect the information that is shared or the way it is analyzed. However, we hope that this research provides a model that other providers can use to evaluate contextual association with clinical outcomes.

This article builds on Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization, later adapted by Ulett et al., to present findings from a mixed-methods study in which we describe the healthcare environment and contextual factors of care that are associated with patients' clinical outcomes. We have added clinic, system, and provider factors to the Andersen/Ulett model to more comprehensively describe a system of care in which more than 86% of the patient population is virally suppressed. Data from our qualitative interviews suggest that salient features of this clinic setting include the 340B funding structure, which can be used to support marginalized patients in receiving care, and the providers' approach to care, which builds on low-threshold, team-based care that builds on harm reduction philosophies. Although further research is needed to explore the degree to which the model of care described here is demonstrated in other settings and with similar results, we propose that this expanded model of health services utilization may offer providers a more comprehensive blueprint of how to engage and retain PLWHA in services to help them achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and patients of Allegheny Health Network Positive Health Clinic who made this research possible. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (awards F31DA037647 to R.W.S.C.) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (TL1TR001858 to R.W.S.C.) of the National Institutes of Health supported this research article. The funding agencies had no involvement in the study design, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethics Approval

The evaluation study from which this work originated was approved via an expedited review by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pittsburgh and the Allegheny-Singer Research Institute/West Penn Allegheny Health System.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: Updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther 2016;13:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapogiannis B, Xu J, Mayer KH. The HIV continuum of care for adolescents and young adults (12–24 years) attending 13 urban US centers of the NICHD-ATN-CDCHRSA SMILE collaborative (Abstract WELBPE16), 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Idele P, Gillespie A, Porth T, et al. . Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: Current status, inequities, and data gaps. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:S144–S153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: Exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:128–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerker BD, Bainbridge J, Kennedy J, et al. . A population-based assessment of the health of homeless families in New York City, 2001–2003. Am J Public Health 2011;101:546–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milloy MJ, Marshall BD, Montaner J, Wood E. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9:364–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale SK, Traeger L, O'Cleirigh C, et al. . Baseline substance use interferes with maintenance of HIV medication adherence skills. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2016;30:215–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: Comparing Housing First with Treatment First programs. Community Ment Health J 2011;47:227–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parruti G, Manzoli L, Toro PM, et al. . Long-term adherence to first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy in a hospital-based cohort: Predictors and impact on virologic response and relapse. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006;20:48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nedelcovych MT, Manning AA, Semenova S, Gamaldo C, Haughey NJ, Slusher BS. The psychiatric impact of HIV. ACS Chem Neurosci 2017;8:1432–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLean CP, Gay NG, Metzger DA, Foa EB. Psychiatric symptoms and barriers to care in HIV-infected individuals who are lost to care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2017;16:423–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. 90–90–90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic, 2014. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf (Last accessed July16, 2016)

- 13.Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, et al. . Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen's Behavioral Model. AIDS Care 2015;27:817–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, et al. . The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Klein DB, et al. . The HIV care cascade measured over time and by age, sex, and race in a large national integrated care system. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:582–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aidala A, Lee G, Abramson D, Messeri P, Sigeler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav 2007;11(Suppl):S101–S115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aidala A, Wilson MG, Shubert V, et al. . Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review. Am J Public Health 2016;106:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, et al. . Associations between substance use, sexual risk taking and HIV treatment adherence among homeless people living with HIV. AIDS Care 2009;21:692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtgrave DR, Briddell K, Little E, et al. . Cost and threshold analysis of housing as an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS Behav 2007;11(6 Suppl):162–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2007;11(6 Suppl):85–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Royal SW, Kidder DP, Patrabansh S, et al. . Factors associated with adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in homeless or unstably housed adults living with HIV. AIDS Care 2009;21:448–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thakarar K, Morgan JR, Gaeta JM, Hohl C, Drainoni M-L. Homelessness, HIV, and incomplete viral suppression. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016;27:145–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolitski R, Kidder D, Fenton K. HIV, homelessness, and public health: Critical issues and a call for increased action. AIDS Behav 2007;11(6 Suppl):167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolitski R, Kidder D, Pals S, et al. . Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2010;14:493–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Risher K, Mayer KH, Beyrer C. HIV treatment cascade in MSM, people who inject drugs, and sex workers. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015;10:420–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos GM, Wilson EC, Rapues J, Macias O, Packer T, Raymond HF. HIV treatment cascade among transgender women in a San Francisco respondent driven sampling study. Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:430–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mountain E, Mishra S, Vickerman P, Pickles M, Gilks C, Boily MC. Antiretroviral therapy uptake, attrition, adherence and outcomes among HIV-infected female sex workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e105645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mountain E, Pickles M, Mishra S, Vickerman P, Alary M, Boily MC. The HIV care cascade and antiretroviral therapy in female sex workers: Implications for HIV prevention. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;12:1203–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vagenas P, Azar MM, Copenhaver MM, Springer SA, Molina PE, Altice FL. The impact of alcohol use and related disorders on the HIV continuum of care: A systematic review: Alcohol and the HIV continuum of care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12:421–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: Current knowledge, implications, and future directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016;40:2056–2072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knowlton A, Arnsten J, Eldred L, et al. . Individual, interpersonal, and structural correlates of effective HAART use among urban active injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41:486–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iroh PA, Mayo H, Nijhawan AE. The HIV care cascade before, during, and after incarceration: A systematic review and data synthesis. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e5–e16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim S, Harris TG, Nash D, Lennon MC, Thorpe LE. All-cause, drug-related, and HIV-related mortality risk by trajectories of jail incarceration and homelessness among adults in New York City. Am J Epidemiol 2015;181:261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim S, Nash D, Hollod L, Harris TG, Lennon MC, Thorpe LE. Influence of jail incarceration and homelessness patterns on engagement in HIV care and HIV viral suppression among New York City adults living with HIV/AIDS. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nijhawan AE. Infectious diseases and the criminal justice aystem. Am J Med Sci 2016;352:399–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beach MC, Duggan PS, Moore RD. Is patients' preferred involvement in health decisions related to outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1119–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach MC, Roter DL, Saha S, et al. . Impact of a brief patient and provider intervention to improve the quality of communication about medication adherence among HIV patients. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1078–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, Beach MC. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63:362–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oetzel J, Wilcox B, Avila M, Hill R, Archiopoli A, Ginossar T. Patient-provider interaction, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes: Testing explanatory models for people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2015;27:972–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okoro O, Odedina FT. Improving medication adherence in African-American women living with HIV/AIDS: Leveraging the provider role and peer involvement. AIDS Care 2015;28:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Continuum of HIV Care: Results. Viral Load Suppression. 2014. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/data/reports/continuumofcare/viralloadsuppression.html (Last accessed December26, 2014)

- 44.Mannheimer SB, Mukherjee R, Hirschhorn LR, et al. . The CASE adherence index: A novel method for measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care 2006;18:853–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawk M, Kinsky S, Coulter R, Friedman M, Egan J, Meanley M. Positive Health Clinic Final Evaluation Report. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Street RL, Jr, O'Malley KJ, Cooper LA, Haidet P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: Personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:198–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heller D, McCoy K, Cunningham C. An invisible barrier to integrating HIV primary care with harm reduction services: Philosophical clashes between the harm reduction and medical models. Public Health Rep 2004;119:32–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilton BA, Thompson R, Moore-Dempsey L, Janzen RG. Harm reduction theories and strategies for control of human immunodeficiency virus: A review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2001;33:357–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Logan DE, Marlatt GA. Harm reduction therapy: A practice-friendly review of research. J Clin Psychol 2010;66:201–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacCoun RJ. Toward a psychology of harm reduction. Am Psychol 1998;53:1199–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marlatt GA, Larimer ME, Witkiewitz K. Harm Reduction, Second Edition: Pragmatic Strategies for Managing High-Risk Behaviors. New York: Guilford Publications, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashman JJ, Conviser R, Pounds MB. Associations between HIV-positive individuals' receipt of ancillary services and medical care receipt and retention. AIDS Care 2002;14:S109–S118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Messeri PA, Abramson DM, Aidala AA, Lee F, Lee G. The impact of ancillary HIV services on engagement in medical care in New York City. AIDS Care 2002;14:S15–S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, et al. . Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: Evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:817–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conti RM, Bach PB. The 340B drug discount program: Hospitals generate profits by expanding to reach more affluent communities. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2014;33:1786–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cushing A, Metcalfe R. Optimizing medicines management: From compliance to concordance. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2007;3:1047–1058 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horberg MA, Hurley LB, Towner WJ, et al. . Influence of provider experience on antiretroviral adherence and viral suppression. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2012;4:125–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Magnezi R, Bergman LC, Urowitz S. Would your patient prefer to be considered your friend? Patient preferences in physician relationships. Health Educ Behav 2015;42:210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Westmoreland P, Mehler PS. Caring for patients with severe and enduring eating disorders (SEED): Certification, harm reduction, palliative care, and the question of futility. J Psychiatr Pract 2016;22:313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van Wormer K, Davis DR. Addiction Treatment: A Strengths Perspective. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Callahan E, Flynn N, Kuenneth C, Enders S. Strategies to reduce HIV risk behavior in HIV primary care clinics: Brief provider messages and specialist intervention. AIDS Behav 2007;11:48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]