Abstract

It is unclear how adults and children differ in their ability to learn distorted speech signals. Normal-hearing adults (≥18 years) and children (8–10 years) were repeatedly tested on vocoded speech perception with 0-, 3-, and 6-mm of frequency-to-place mismatch (i.e., shift). Between testing blocks, listeners were provided training blocks with feedback on the 6-mm shift condition. Adults performed better than children at 0-mm shift, but performed similarly at 3- and 6-mm shifts. Therefore, differences between adults and children in vocoded speech perception are dependent on the degree of distortion, and this difference seems unaltered by training with feedback.

1. Introduction

A cochlear implant (CI) is a sensory prosthesis that can partially restore speech understanding to individuals with severe-to-profound sensorineural hearing loss. Although CIs provide users access to auditory input, variability in speech perception abilities is found among CI users. In an attempt to avoid this variability, researchers can acoustically simulate the degradation produced by a CI sound processor with a channel vocoder, testing a relatively more homogeneous group of normal-hearing (NH) individuals. In vocoding, speech is separated into frequency channels and the temporal envelope is used to convey speech information. One approach when using a sine-wave vocoder is to independently vary the analysis and synthesis filter frequencies, thus shifting the speech information to another tonotopic location. The reason to introduce a frequency shift is to simulate frequency-to-place mismatch or shallow insertion depth of the intracochlear device. Because it is difficult to insert the arrays into the apical turn of the cochlea, even standard implantations will lead to some degree of frequency-to-place mismatch (Landsberger et al., 2015). This is because the apical end of the cochlea, which is sensitive to lower frequencies, likely does not receive sufficient electrical stimulation from a shallow insertion. Attempting to align frequency to place in most CI users that have shallow insertion depths would drop frequency information critical for speech understanding (Faulkner et al., 2003). In addition, many CI users require a period of adaptation to this frequency-to-place mismatch before they can understand speech proficiently (Fu and Galvin, 2008).

Although initial speech perception performance is poor when listening to shifted vocoded speech (e.g., Shannon et al., 1995), NH adults can adapt to frequency-to-place mismatch after explicit training. For example, Rosen et al. (1999) showed that training with connected discourse tracking (CDT) improves the identification of intervocalic consonants, medial vowels in monosyllabic words, and sentence comprehension. Each session consisted of CDT and testing in three conditions: unprocessed, unshifted four-channel vocoded, and 6.4-mm-shifted four-channel vocoded. Word identification in the shifted vocoded condition began at 1%, improved steadily over the ten testing sessions, and saturated at 30%, but never reached the 64% found in the unshifted vocoded condition prior to training. This was also true for detecting the feature of place of articulation among consonant sounds, but not for the features of voicing and manner.

While a number of studies that have trained listeners to understand vocoded speech have been conducted on NH adults, it is unclear how training impacts understanding of vocoded speech, unshifted or shifted, in children (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Nittrouer et al., 2009; Newman et al., 2015). In acute studies (i.e., those that lack explicit training) with no frequency shift, young children 3–7 years of age performed more poorly than adults on vocoded speech understanding (Dorman et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 2000; Nittrouer et al., 2009), whereas children 10–12 years of age performed similarly to adults (Eisenberg et al., 2000).

In this study, we sought to determine (1) if adults and children differed in vocoded speech perception with varying degrees of frequency-to-place mismatch and (2) if explicit training produced different rates of improvement across these two populations. If children demonstrate relatively more plasticity to frequency shift than adults, then age-related differences may disappear after exposure and training. Alternatively, if children have a natural inability to process vocoded speech, then differences between adults and children should persist or become larger after exposure and training. Such information will inform us about age-related differences in speech processing and learning how to process informationally sparse signals.

2. Method

2.1. Listeners

Nineteen adults between the ages of 19 and 23 years (20.7 years on average) and seventeen children between the ages of 8 and 10 years (8.9 years on average) were tested. Most adult listeners were University of Maryland undergraduate students. Child listeners were recruited via the University of Maryland Infant and Child Developmental Database or from the local community. All listeners had normal audiometric thresholds of 20 dB HL (hearing level) or less at octave frequencies between 250 and 8000 Hz, were native English speakers, and had no known cognitive/linguistic delays or disorders/differences. Listeners had no experience with vocoded speech prior to the experiment.

2.2. Stimuli

Stimuli in this experiment consisted of five single-syllable words played sequentially to make a closed-set of low-context sentences, such as “Pat saw two red bags” or “Jill took five small hats” (Kidd et al., 2008). This corpus was selected because it consisted of elementary-level words and was therefore appropriate for the children in this experiment. Words were spoken by a single female speaker.

We sought to potentially amplify the age-related differences in vocoded speech perception by including frequency-to-place mismatch, which shows large training effects (e.g., Rosen et al., 1999). This also reduces the chances of ceiling effects because performance becomes worse with increasing shift. Stimuli were band-pass filtered into eight channels using fourth-order Butterworth filters. The corner frequencies were logarithmically spaced and covered a frequency range from 200 to 5000 Hz. The speech envelopes were extracted using a second-order low-pass filter with a 32-Hz cutoff frequency and were used to modulate sine-wave carriers. A relatively low envelope cutoff was used to keep the sidebands generated by the modulations from being spectrally resolved (i.e., they remained within a single auditory filter). Resolved sidebands greatly improve vocoded speech perception (Souza and Rosen, 2009) and would have introduced a potential confound for the shifted stimuli. Using the Greenwood (1990) formula, the carrier frequencies were linearly shifted by 0, 3, or 6 mm. For example, the lowest channel center frequency started at 244 Hz and became 445 Hz for a 3-mm shift or 748 Hz for a 6-mm shift. For the shifted conditions, a loudness correction was used to diminish differences in performance across the conditions based on level or audibility of the speech information. The loudness compensation adjusted the level in dB by 50% between the threshold for the unshifted and shifted carrier frequencies, where threshold was based on the minimum audible field curve (Faulkner et al., 2003). Stimuli were then synthesized by summing the channels into the acoustic waveform and normalized to have equal root-mean-square energy as the unprocessed speech.

2.3. Procedure

Stimuli were delivered using a soundcard (UA-25 EX, Edirol/Roland Corp., Los Angeles, CA), amplifier (D-75A, Crown Audio, Elkhart, IN), and circumaural headphones (Sennheiser, HD650, Hanover, Germany). Testing occurred in a double-walled sound attenuated booth (Industrial Acoustics Inc., Bronx, NY). Children were accompanied by an experimenter in the sound booth and did not directly control the computer; adults were unaccompanied.

The experiment was controlled by a computer interface that had five columns of words, each with eight possible choices. Adult listeners initiated each trial with a button press and were instructed to select one word from each column after every trial. Child listeners told the accompanying researcher when they were ready to begin a new trial and what words they believed they had heard. Researchers controlled the interface as instructed by child listeners. Listeners in both groups were told to provide their best guess whenever they were unsure of what they had heard. After one item was selected from each column, the trial ended after another button press.

The experiment duration was four hours per listener. The experiment alternated between testing and training blocks. Each testing block consisted of 45 vocoded sentences with 0-, 3-, and 6-mm shifts. There were 15 sentences per shift condition, the order of presentation was random, and no correct answer feedback was provided. Each training block consisted of 30 vocoded sentences with 6-mm shift. Training with only the largest frequency shift of 6.4 mm was also used in Rosen et al. (1999). After each trial in a training block, visual feedback was provided by highlighting the correct word on the computer interface and auditory feedback was provided by playing the unprocessed sentence followed by vocoded sentence (Davis et al., 2005). Adults completed 12 testing and 11 training blocks in four hours. Children were slower because they need more frequent and longer breaks, and therefore completed five testing and four training blocks in four hours.

The percentage of correctly identified words was calculated for each vocoded sentence. Percent correct scores were transformed into rationalized arcsine units (RAUs; Studebaker, 1985) before inferential statistics were performed. In cases where the assumption of sphericity was violated in a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA), the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom.

3. Results

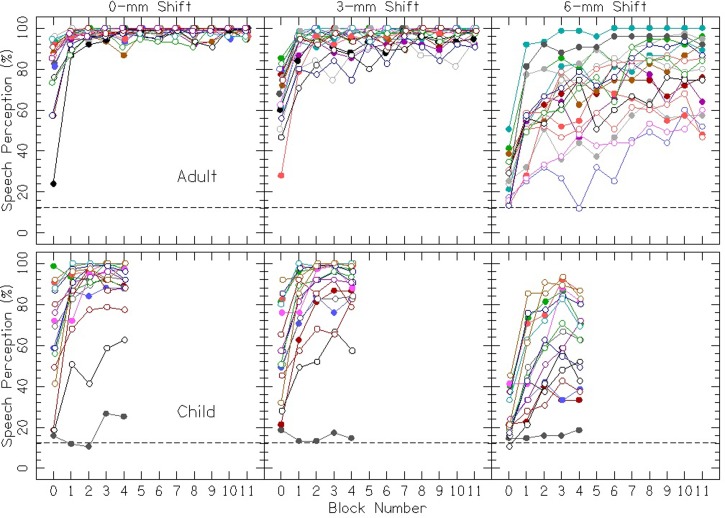

Figure 1 shows individual data presented as percent correct scores. The most important feature to note in this figure is that vocoded speech perception was highly variable within each group. For example, the acute performance (block 0) for both adults and children for the 6-mm shift condition ranged from about 12.5% (chance performance) to 50% correct. This variability also persisted throughout the experiment. A two-tailed partial correlation controlling for age showed that acute performance (block 0) was highly correlated with trained performance (block 4; p < 0.001 for all three shifts), suggesting that this variability is mostly inherent to the listener rather than a result of the experiment.

Fig. 1.

(Color online) Speech perception in percent correct for the adult (top row) and child (bottom row) listeners as a function of block number. The dashed line shows chance performance (12.5%).

Because children required more time to complete the experiment, they were only able to complete five testing blocks in the four hours of testing, rather than the twelve blocks completed by adults. Because of this, we chose to compare child and adult listeners for the first five blocks of testing. This decision was supported by post hoc Helmert contrasts that were performed independently on each degree of shift; performance effectively plateaued by the fourth block for all three shifts in both groups (p > 0.05 for all six contrasts).

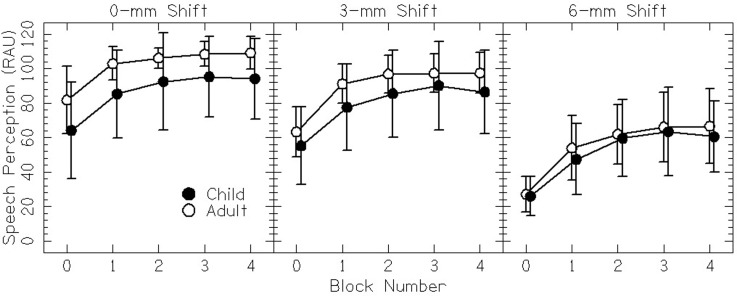

Figure 2 shows the average data for both age groups over the first five testing blocks. A mixed ANOVA with two within-subjects factors (shift and block) and one between-subjects factor (age) was performed. Performance decreased with increasing shift [F(1.2,1.9) = 308, p < 0.0001, = 0.90], indicating that shift decreases speech perception. Performance increased with increasing block number [F(1.9,63.8) = 153, p < 0.0001, = 0.82], indicating that exposure from testing along with training with feedback improves vocoded speech perception. There was no significant difference between the performance of the two age groups [F(1,34) = 3.22, p = 0.082, = 0.09], indicating that adults and children do not significantly differ in vocoded speech perception for this corpus; however, significant interactions highlighted differences between the groups. There was a significant age × shift interaction [F(1.9,63.8) = 3.61, p = 0.035, = 0.10], indicating that adults outperform children, but only at certain shifts. There was also a significant block × shift interaction [F(3.99,135.2) = 2.8, p = 0.028, = 0.08], indicating that listeners' performance improved more across blocks as the degree of shift increased. The age × block and age × block × shift interactions were not significant (p > 0.05 for both).

Fig. 2.

Speech perception performance in RAUs for both adult and child listeners as a function of block number. Error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation.

To further explore the age × shift interaction, separate two-way mixed ANOVAs were carried out for each degree of shift, with block number as the within-subject factor and age as the between-subject factor. There was a significant main effect of block for the 0-mm [F(2.2,73.8) = 51.2, p < 0.0001, = 0.60], 3-mm [F(2.1,170.9 = 104.2, p < 0.0001, = 0.75], and 6-mm shift [F(2.5, 85.5) = 106.8, p < 0.0001, = 0.76], indicating that listeners improved for all three shifts. There was a significant main effect of age for the 0-mm condition [F(1,34) = 7.01, p = 0.012, = 0.17], but not in the 3-mm [F(1,34) = 3.11, p = 0.087, = 0.08], or 6-mm [F(1,34) = 0.42, p = 0.52, = 0.01] conditions, indicating that adults were significantly better at vocoded speech perception only at the 0-mm shift. There were no significant age × block interactions (p > 0.05 for all three shifts). In conclusion, we found that adults were significantly better at vocoded speech perception but only for the 0-mm shift condition, and that adults and children did not significantly differ at the rate at which they improved at vocoded speech perception.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine how 8–10 year old children and adults perceive vocoded speech at different degrees of frequency shift and if any age-related differences in performance change after exposure and training. We hypothesized that children in this age range would adapt to frequency shifted speech faster than adults because of greater neural plasticity, as shown in long-term language learning studies (e.g., Krashen et al., 1979).

The results in Figs. 1 and 2 show that for both age groups, performance decreased with increasing shift, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Rosen et al., 1999). Results also show that both groups improve with exposure and training for all three degrees of shift with the largest improvements for the largest shift, also consistent with previous studies (e.g., Rosen et al., 1999; Davis et al., 2005).

There was no main effect of age; however, there was a significant age × shift interaction, best observed in Fig. 2, indicating that the difference between groups varied with condition. Adults performed significantly better than children for the 0-mm shift condition, but there was no significant difference between the two groups for the 3- and 6-mm shift conditions. Vocoding removes much of the potentially redundant speech information from a signal by replacing the temporal fine structure and smearing spectral cues. Apparently adults, in the unshifted condition, can utilize this mostly unaltered and sparse amount of information more effectively than children. Only when the spectral cues are substantially altered with 3 or 6 mm of tonotopic shift, do adults and children perform equally. At this point, it may be that both groups need to relearn the spectral features of the speech signal. One explanation for these data is that it is possible that frequency shifts interfere with adults' ability to access top-down information. Using an eight-channel vocoder reduces available information. Without frequency shift, the vocoder might not reduce how well the remaining acoustic information maps onto existing representations in the adult listeners' lexicon. With frequency shift, the vocoder might have a larger influence on how acoustic information maps onto lexical representations, thus resulting in adults and children preforming similarly for these conditions.

Other studies have also compared how adults and children differ in vocoded speech perception; however, those studies did not include training and did not introduce tonotopic shift. Eisenberg et al. (2000) studied three separate age groups: 5–7 year old children, 10–12 year old children, and adults over the age of 18. Listeners were tested using the relatively easy Hearing In Noise Test for Children (HINT-C) sentences and the Phonetically Balanced Word Lists-Kindergarten single words. Stimuli were vocoded with 4, 6, 8, 16, and 32 channels and noise carriers. They found that the older children and adults performed similarly and the younger children were worse. For the eight-channel sentence condition (the number of channels used in the current study), the mean scores were 82%, 93%, and 94%, for the younger children, older children, and adults, respectively. Nittrouer et al. (2009) studied 7 year old children and adults using relatively difficult four-word nonsense sentences, vocoded with four and eight channels and noise carriers. They found that children were worse than adults in both the eight (38% for children and 62% for adults) and four (14% for children and 27% for adults) channel conditions. Dorman et al. (2000) studied 4–6 year old children using easy and hard sentences from the Multisyllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test (MLNT), vocoded with 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 channels and sine tone carriers. They found children were worse than adults, particularly for the more difficult sentences and smaller numbers of channels (approximately 70% for children and 85% for adults at eight channels). In the current experiment, we studied 8–10 year old children using a corpus that was on one hand relatively easy because of the small set of words in the closed set sentences but on the other hand was difficult because of the lack of semantic context; these sentences were vocoded with eight channels and sine-wave carriers. We found that children were worse than adults for this condition (78% for children and 93% for adults at 0-mm shift). To summarize, it appears that children are worse than adults at understanding vocoded speech, at least up to 8–10 years old, and that the difficulty of the materials and the implementation of the vocoding (e.g., the number of channels) should be considered as potentially confounding variables. Improvement in vocoded speech perception occurred at the same rate in both groups, yielding no significant interactions with block number (i.e., amount of exposure and training). Therefore, we predict that the age-related differences would have persisted after training in all of the aforementioned studies. It is interesting that introducing difficulty by decreasing the number of channels in these three other studies increased the age-related differences in vocoded speech perception, which is the opposite of what occurs when introducing difficulty by increasing tonotopic shift. Increasing tonotopic shift decreased the age-related differences, which by 3- and 6-mm shifts, made performance across our groups not statistically different. This again highlights that adults appear to be better able to handle spectral smearing than children, but only when there is no large spectral distortion through frequency-to-place mismatch.

Last, it is noteworthy that Fig. 1 showed very highly variable data, particularly for the 6-mm shift, where there was little effect of the ceiling. This variability persisted after exposure and training, and it is possible that this variability is obscuring some age-related differences. A major reason to use a vocoder and test NH listeners is to reduce the characteristic variability in CI performance that is thought to result from biological, surgical, and device-related factors. NH listeners are assumed to be absent of these differences, meaning that the stimuli are transduced by the auditory periphery in essentially the same way. Assuming similar encoding by the auditory system, the variability suggests that other more central and/or cognitive and linguistic factors could play a role in understanding vocoded speech, particularly when shifted. Future work investigating the nature of these individual differences, perhaps related to cognitive or linguistic abilities, would be informative as they may also apply to CI users.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Reem Bechara for help with data collection. We would like to thank Miranda Cleary and Rochelle Newman for feedback on a previous version of this work. This work was supported by NIH Grant No. R01-DC014948 (M.J.G.). Portions of this study were presented at the 167th Acoustical Society of America Meeting in Providence, RI.

References and links

- 1. Davis, M. H. , Johnsrude, I. S. , Hervais-Adelman, A. , Taylor, K. , and McGettigan, C. (2005). “ Lexical information drives perceptual learning of distorted speech: Evidence from the comprehension of noise-vocoded sentences,” J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 134, 222–241. 10.1037/0096-3445.134.2.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dorman, M. F. , Loizou, P. C. , Kemp, L. L. , and Kirk, K. I. (2000). “ Word recognition by children listening to speech processed into a small number of channels: Data from normal-hearing children and children with cochlear implants,” Ear Hear. 21, 590–596. 10.1097/00003446-200012000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eisenberg, L. S. , Shannon, R. V. , Martinez, A. S. , Wygonski, J. , and Boothroyd, A. (2000). “ Speech recognition with reduced spectral cues as a function of age,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 107, 2704–2710. 10.1121/1.428656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faulkner, A. , Rosen, S. , and Stanton, D. (2003). “ Simulations of tonotopically mapped speech processors for cochlear implant electrodes varying in insertion depth,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113, 1073–1080. 10.1121/1.1536928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu, Q. J. , and Galvin, J. J., 3rd (2008). “ Maximizing cochlear implant patients' performance with advanced speech training procedures,” Hear. Res. 242, 198–208. 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greenwood, D. D. (1990). “ A cochlear frequency-position function for several species—29 years later,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87, 2592–2605. 10.1121/1.399052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kidd, G., Jr. , Best, V. , and Mason, C. R. (2008). “ Listening to every other word: Examining the strength of linkage variables in forming streams of speech,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 124, 3793–3802. 10.1121/1.2998980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krashen, S. D. , Long, M. A. , and Scarcella, R. C. (1979). “ Age, rate and eventual attainment in second language acquisition,” TESOL Quart. 13, 573–582. 10.2307/3586451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landsberger, D. M. , Svrakic, M. , Roland, J. T., Jr. , and Svirsky, M. (2015). “ The relationship between insertion angles, default frequency allocations, and spiral ganglion place pitch in cochlear implants,” Ear Hear. 36, e207–e213. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newman, R. S. , Chatterjee, M. , Morini, G. , and Remez, R. E. (2015). “ Toddlers' comprehension of degraded signals: Noise-vocoded versus sine-wave analogs,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 138, EL311–EL317. 10.1121/1.4929731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nittrouer, S. , Lowenstein, J. H. , and Packer, R. R. (2009). “ Children discover the spectral skeletons in their native language before the amplitude envelopes,” J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 35, 1245–1253. 10.1037/a0015020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosen, S. , Faulkner, A. , and Wilkinson, L. (1999). “ Adaptation by normal listeners to upward spectral shifts of speech: Implications for cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 3629–3636. 10.1121/1.428215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shannon, R. V. , Zeng, F. G. , Kamath, V. , Wygonski, J. , and Ekelid, M. (1995). “ Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues,” Science 270, 303–304. 10.1126/science.270.5234.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Souza, P. , and Rosen, S. (2009). “ Effects of envelope bandwidth on the intelligibility of sine- and noise-vocoded speech,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 126, 792–805. 10.1121/1.3158835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Studebaker, G. A. (1985). “ A ‘rationalized’ arcsine transform,” J. Speech Hear. Res. 28, 455–462. 10.1044/jshr.2803.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]