Abstract

The purpose of this work is to analyze the frequency of depression and anxiety and children behaviour in families whose heads of the family (father) suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The study was conducted from September 2005 until July 2006, with patients living in Mostar. The frequency of depression and anxiety in family members older than 18 years, and changes of the behaviour in children younger than 18 years of age were measured. The data were collected from 60 men and their families who had been diagnosed with PTSD by their psychiatrist. The control group was formed using matching criteria (age of the head of the family, his education, religion, family income and number of children). In this study, three questionnaires were used: one specially designed for this study, covering general information about family members, and a personal opinion of each family member about the family situation and relations within the family; Hopkins symptoms checklist - 25 (HSCL-25) for evaluation of depression and anxiety for subjects older than 18; and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) for children 5 to 18 years of age, which was completed by their mothers.

More wives from the PTSD families had depression than wives from the controlled group (χ2=21,099; df=1; P<0,050). There was no difference between groups in frequency of depression and anxiety (χ2=0,003; df=1; P=0,959) for children older than 18 years. No difference in answers between groups of children younger than 18 years were found in the General Health Questionnaire. However, we found significant differences in separate questions. Mothers, who filled the questionnaire form, reported that children from fathers who had PTSD experienced stomach pain more often (χ2=10,474;df=2; P=0,005), eating problems (χ2=14,204;df=2; P=0,001) and breathing problems (χ2=9,748;df=2; P=0,008), than children from fathers who did not have PTSD. Children from fathers with PTSD were more easily upset (χ2=7,586; df=2; P=0,023) and worried more often (χ2=12,093; df=2; P=0,002), they were also more aggressive towards other children (χ2=6,156; df=1; P=0,013). The controlled group of children who wanted to help with the house work was larger than the tested group (χ2=10,383; df=2; P=0,006). More children from the controlled group missed school than from the other group of surveyed children (χ2=6,056; df=2; P=0,048).

A significantly larger number of women, whose husbands had PTSD, were depressed, unlike women whose husbands were not ill. There was no significant difference in depression manifestation in a group of children older than 18, as well as in behaviour of a group of children younger than 18, but significant differences in some provided answers were found, that indicate the differences between controlled and tested groups.

Keywords: family, PTSD, war, family health, parent-child relations

INTRODUCTION

When diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was introduced in 1980, traumatic events sufficient to induce this condition were considered rare (1). Since then, epidemiologic surveys have documented such events to be highly prevalent, with 50-90% of the population exposed over the course of a lifetime. Lifetime prevalence of PTSD is approximately 8% (2). Thompson et al. (3) showed results from two large independent studies, funded by the US government about the impact of the Vietnam War on the prevalence of PTSD in US veterans. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study estimated the current PTSD prevalence to be 15,2%, while the Vietnam Experience Study estimated the prevalence to be 2,2%. People’s exposure to traumatic events in general, and the development of PTSD in particular, are associated with poor physical health and increased rates of physician-diagnosed medical conditions (4). Moreover, people with PTSD often engage in behaviours associated with negative effects on health, such as alcohol and drug abuse or dependence (4). Epidemiological and clinical studies have shown that combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder was frequently associated with other psychiatric disorders (5). Australian Vietnam veterans who suffer from PTSD report enduring interpersonal relationship difficulties (6). It is unclear, however, where the source of their interpersonal troubles lies. Studies in this area have associated the conflict and distress in family and couple relationships to PTSD symptoms (6). This assumption appears reasonable given that the symptoms of PTSD are likely to produce affective and behavioural consequences consistent with poor relationship functioning. For example, the tendency of PTSD sufferers to avoid any emotionally tense situations could be a source of frustration for partners (6). While veterans were traumatized directly by the war, their wives and families became indirect victims of the trauma. Psychic trauma may create ripples which affect not only the victims themselves, but also those who are close to them (7). Previous studies have reported that the wives of PTSD veterans are subjected to increased physical violence, as well as emotional and verbal abuse (8). Marital relations appear to be particularly vulnerable to the negative consequences of traumatic combat experiences, with distress levels in wives virtually paralleling those of their husbands (8). Veterans’ wives reported heightened levels of psychological maltreatment by their husbands. Veterans’ combat exposure was positively correlated with hostility and violent behaviour among children (9). Jordan and colleagues (10) found that children of Vietnam veterans with PTSD were significantly more likely to have behavioural difficulties (as reported by their mothers) than children of veterans without PTSD. Using a similar rating scale, Person and colleagues (11) reported that children of veterans with PTSD showed more behavioural problems than children of veterans without PTSD, including aggression, delinquency, hyperactivity and difficulty in developing and maintaining close friendships. Several clinical and empirical studies have reported lower self-esteem, poorer family functioning and emotional and psychiatric disturbances in both wives and children of Vietnam veterans with PTSD (12). We assumed that depression and anxiety were more often present among the members of the families (wives, and children older than 18 years of age), whose heads have developed PTSD, than among matched controlled groups. Missing from the study is that we do not know a level of vigor of symptoms of fathers, and if the level of this difference has an influence on other members of the family. Furthermore, the data were not available regarding the direct exposure of the family members to the war activities and if that fact had any influence on the results of the study. The aim of the study was to show doctors in primary care the big problem of secondary traumatization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The data were collected in the period from September 2005 until July 2006. The health charts from 60 people who had earlier been diagnosed with PTSD by their psychiatrist were selected. The study included patients who had come to the Department of Family Medicine in the Health Care Center Mostar. Patients filled out questionnaires during their visits to the Health Care Center Mostar, or when they were referred to the Center by their psychiatrist. After the head of a family with PTSD was identified, the information about the age of the head of the family, his education, religion, total family income, and number of children, was used to find his “healthy” pair as matching criteria. All patients from the controlled group were selected among the outpatients of the Health Care Center Mostar. Data from patients at the Health Centre in Mostar were collected by the author from the Center and from the other family members in their homes.

Methods

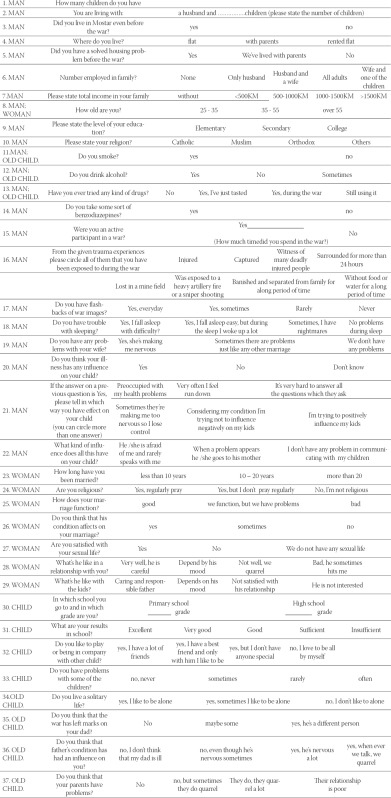

To collect general information about the family, subjective opinion of the family members, and their mutual relations, a questionnaire specially designed for this study was used (Appendix 1). The designed questionnaire consisted of several parts, intended for different members of the family. The Hopkins symptoms questionnaire (HSCL-25) (13) was used for evaluation of depression and anxiety in mothers and children older than 18 years. The examinees personally filled out the HSCL-25 questionnaire. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (14) was filled out by the mothers and used to evaluate general health and behaviour in children from 5 to 18 years of age. The purpose of this questionnaire was to determine if there was any change in the health and behaviour of the children. In the beginning, a pilot study with 15 patients and their families, who had come to the Health Care Center Mostar was conducted, with aim to check if the participants understood all the questions. The pilot study showed that the questionnaire did not need to be modified.

Statistical analysis

The differences between the groups were tested with a χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test has been used only on a smaller sample. The level of significance was set at P<0,05. Statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Science for Windows v. 12.0 (SPSP Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

One hundred and twenty families were tested, 60 with fathers who had PTSD and 60 with fathers without PTSD. There were a total of 155 children in the study group, and 103 of these children lived with their families. There were 156 children in the control group, but only 109 children who were tested lived with their parents. The children who had their own families or who lived separately from their parents were not included. In the group of families whose fathers had PTSD, the highest proportion of families had only one child (45%), whereas in the control group 53,3% of families had two children (Table 1). The families with fathers who developed PTSD had a higher unemployment rate for all members of the family (30%), than the control families (11,7%). In the control group (38,3%), both husbands and wives were more frequently employed (38% vs. 10%, χ2=13,983; df=4; P<0,001, Table 1). In the group of families with fathers with PTSD, 43,3% had a total income that was less than 500 KM (1 KM=1,958 €) and in the control group there was 35% (χ2=3,517; df=4; P=0,475). When questioned about relationships between husbands and wives in both groups, men answered that their relationships were good (χ2=2,540; df=2; P=0,111). However, when wives were asked the same question, 83,3% of wives from the study group, and 66,7% of wives from the control group answered that this relationship depends on the husband’s mood (χ2=10,370; df=3; P=0,005, Table 2). Only fathers with PTSD were asked about the influence of their illness on their children, and within them 65% answered that their illness influenced their children, 11,7% did not think that their illness had any influence on their children, and 23,3% could not decide what to answer (χ2=28,300; df=2; P<0,001). Mothers from the study group stated (76,7%) that the relationship between their husband and children depended on his mood, unlike wives in the controlled group (33,3%) (χ2=29,377; df=3; P<0,001, Table 2). The Hopkins questionnaire revealed that women from the study group have been more often depressed (55%), than women from the controlled group (15%, χ2=21,099; df=1; P<0,001). There was no difference in depression for children older than 18 years. In both groups, the depression score was less than 1,75, indicating no significant depression (χ2=0,003; df=1; P=0,959). The wives from the study groups (68,3%) were religious and they regularly prayed, and in the controlled group, 33,3% of wives were religious (χ2=22,200; df=2; P<0,001). Looking at the connection between faith commitment and problems in marriage in the study group, 56,7% of religious wives who regularly prayed stated that their marriage was good, regardless of the problems what proved to be the most frequent answer (χ2=39,876; df=4; P<0,001, Table 3). The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) did not reveal any differences between the studied groups, so each question was analyzed separately. In the test group more children had stomach pain and vomiting (χ2=10,474; df=2; P=0,005), eating problems (χ2=14,204; df=2; P=0,001), and breathing problems (χ2=9,748; df=2; P=0,008), than children who had fathers without PTSD (Table 4). In the study group children were more frequently upset (χ2=7,586; df=2; P=0,023) and worried, and quarreled more frequently (χ2=12,093; df=2; P=0,002). Children younger than 18 years from controlled families wanted to help with housework (partly and always) more often than the study group children (χ2=10,383; df=2; P=0,006). Children from the study group missed school significantly less than children from the controlled group (χ2=6,056; df=2; P=0,048, Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We found that wives of veterans with PTSD experienced depression more frequently than wives from the control group, while children older than 18 years did not differ in depression compared to controlled children. It is obvious that living with traumatized persons significantly influences other family members, especially wives, who are expected to be empathic and to provide the greatest support to their ill husbands (15). Previous research showed that close and long-term contact with an emotionally disturbed person may cause chronic stress. In time, this may lead to various emotional problems, such as higher levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety, problems in concentration, emotional exhaustion, pain syndromes and sleeping problems to the person providing the help (15). In the controlled group, more family members were employed than in the study group. This corresponds to the findings of Davidson and Mellor (12), who studied veterans and their children compared to civilian adult men and their children. They found that a large number of veterans were retired and not in the labor force (35%); and both veterans and their children were more likely to be unemployed (10% vs. 0% for the adults; 12% vs. 10% for the children) than their civilian counterparts. In our study, despite the fact that families with fathers who did not develop PTSD had more people employed in their families, the total family income did not differ significantly. Therefore, the total family income did not affect the relationship between husbands and wives. More wives from the study group thought that their relationship with their husbands and the relationship between the husband and their children depended on the mood of the father. According to the literature value over 70% of the PTSD veterans and their partners reported clinically significant levels of relationship distress compared to only 30% of the non-PTSD couples (16). The degree of the relationship distress was correlated with the severity of veterans’ PTSD symptoms, particularly symptoms of emotional numbing (16). The relationships have been characterized by increased levels of conflict and violence, and decreased levels of self-disclosure, sociability, affection, intimacy and cohesion (9). The depression scores, obtained with the Hopkins symptoms questionnaire, did not differ between surveyed children. Data from the General Health Questionnaire showed no difference in answers between tested and controlled groups in children younger than 18 years of age. Our results were surprising, because we expected more father’s influence on offspring. Results from HSQ might be explained by the fact that children older than 18 years have other interests such as attending universities, sports, music, etc., that protect them from the levels of distress. GHQ did not show differences, however answers to individual questions from the survey differed significantly. Mothers, who filled the questionnaire form, reported that children with fathers who had PTSD experienced stomach pain more often, as well as eating problems and breathing problems, than children with fathers without PTSD. This can be related to the fact that these children are somatising their psychological problems. Children whose fathers had PTSD were upset more easily, were more often worried, which could be associated with the decreased level of frustration tolerance. They were more aggressive towards other children, presumably because these children use their fathers as a role model in social behaviour. The controlled group of children who wanted to help with the house work was larger than the studied one. Children from the study group were not often in a good mood, and they did not help in the household and gardening work. This finding might be connected to the transfer of bad relations from their homes. More children from the controlled group missed school than children from the studied group. This result might be explained by the fear that tested children have of their fathers, who might react violently towards them if they find out about missing school classes. Our results show that children in the age group under 18 years have problems associated with behaviour and health, which is in line with the data of Beckham et al. (17), who reported problems with separation and individuation, pathological identification with their traumatized parents, depression, guilt, and characteristic PTSD symptoms. In addition, our findings agree with reported data: children of Vietnam veterans with PTSD were significantly more likely to have behavioural difficulties (as reported by their mothers) than children of veterans without PTSD reported from (10); children of the veterans reported significantly higher levels of conflict in their families; families of veterans with PTSD experienced more problems in parenting as well as marital relationships (18), and children of veterans with PTSD showed more behavioural problems including aggression, delinquency, hyperactivity and difficulty in developing and maintaining close friendship than children of veterans without PTSD (11). Although we did not find such behavioural problems, our findings suggest that some behavioural problems do exist in children who have fathers diagnosed with PTSD. This study has a few limitations. It analyzed the influence of father’s PTSD on family members more than 10 years after the conflict had ended. PTSD symptoms can either increase or decrease over a number of years (20). The data on the level of manifestation of fathers’ PTSD symptoms are not known, as well as if the differences in symptoms had any implications on other family members. Furthermore, the data was not available regarding the direct exposure of the family members to the war activities and if that fact had any influence on the results of the study. Further studies should include the effect of direct exposure of family members to the war activities on manifestation of depression and disorders related to altered behaviour in children.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the influence of secondary traumatization of wives is significant. There are more women in the tested group with expressed symptoms of depression. Although we did not find significant differences in depression in children older than 18 or differences in behaviour in younger children, we found that children whose fathers had PTSD were upset more easily, were more often worried, they were somatising their psychological problems, and they were more aggressive towards other children. This fact did not have any importance to our study, but it could be important to follow these children in the future and research possible cumulative impact on the psychical health pattern.

Acknowledgments

Dr. John A Geddes BSc, MSc, MD, CCFP; Assistant Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Queen’s Universtiy, Kingston, Ontario, Canada; Queen’s University Family Medicine Development Program in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

APPENDIX 1

Please answer truly and in accordance with your experience on the given questions. Circle the letter in front of the answer which is applied to you. In the questionnaire there are no correct or false answers.

After you answer all the questions, please return he questionnaire by mail on an address which is on the envelope, at the expense of the author We are thankful for you cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schnurr P.P, Friedman M.J, Bernardy N.C. Research on post-traumatic stress disorder: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and assessment. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002;58:877–889. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vieweg W.V, Julius D.A, Fernandez A, Beatty-Brooks M, Hettema J.M, Pandurangi AK. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinical features, pathphysiology, and treatment. Am J Med. 2006;119:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson W.W, Gottesman I.I, Zalewski C. Reconciling disparate prevalence rates of PTSD in large samples of US male Vietnam veterans and their controls. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez B.F, Weisberg R.B, Pagano M.E, Macham J.T, Culpepper L, Keller M.B. Mental health treatment received by primary care patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003;64:1230–1236. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivezić S, Bagarić A, Oruč L, Mimica N, Ljubin T. Psychotic symptoms and comorbid psychiatric disorder in Croatian combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Croat. Med. J. 2000;41(2):179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans L, McHugh T, Hopwood M, Watt C. Chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and family functioning of Vietnam veterans and their partners. Aust. N Z J. Psychiatry. 2003;37(6):765–772. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2003.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon Z. The impact of war stress on veterans families. [[accessed 25.11.2006]]. http://www.ffzg.hr/hsd/polemos/drugi/2.html .

- 8.Solomon Z. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder in military situations. J Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62(17):11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glenn D.M, Beckham J.C, Feldman M.E, Kirby A.C, Hertzberg M.A, Moore S.D. Violence and hostility among families of Vietnam veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence Vict. 2002;17(4):473–489. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.4.473.33685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan B.K, Marmar C.R, Fairbank J.A, Schlenger W.E, Kulka R.A, Hough R.L, Weiss D.S. Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992;60(6):916–926. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons J, Kehle T.J, Owen S.V. Incidence of behaviour problems among children of Vietnam war veterans. School Psychology International. 1990;11:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson A.C, Mellor D.J. The adjustment of children of Australian Vietnam veterans: is there evidence for the transgenerational transmission of the effects of war-related trauma. Aust. N Z J. Psychiatry. 2001;35(3):345–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins symptoms checklist-25. Bosnia and Herzegovina. [[accessed 01.12.2006]]. www.hprt-cambridge.org/Layer3.asp?pageid=10 .

- 14.Goodman R. A modified version of the Rutter parent questionnaire including extra items on children’s strengths: A research note. J Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 1994;35(8):1483–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frančišković T, Stevanović A, Jelusić I, Roganović B, Klarić M, Grković J. Secondary traumatization of wives of war veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Croat. Med. J. 2007;48:177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riggs D.S, Byrne C.A, Weathers F.W, Litz B.T. The quality of the intimate relationships of male Vietnam veterans: problems associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma Stress. 1998;11(1):87–101. doi: 10.1023/A:1024409200155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beckham J.C, Braxton L.E, Kudler H.S, Feldman M.E, Lytle B.L, Palmer S. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles of Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and their children. J. Clin. Psychol. 1997;53(8):847–852. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199712)53:8<847::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westerink J, Giarratano L. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on partners and children of Australian Vietnam veterans. Aust. N Z J. Psychiatry. 1999;33(6):841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yehuda R, Halligan S.L, Bierer L.M. Relationship of parental trauma exposure and PTSD to PTSD, depressive and anxiety disorder in offspring. J. Psychiatry Res. 2001;35(5):261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasanović M, Sinanović O, Pavlović S. Acculturation and psychological problems of adolescents from Bosnia and Herzegovina during exile and repatriation. Croat. Med. J. 2005;46(1):105–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]