Highlights

-

•

Spontaneously regressing cancers are extremely rare, but been known to occur in almost all types of malignant tumors.

-

•

Spontaneous regression of pancreatic cancer is especially rare as compared to other types of malignancies.

-

•

Importance correlating factors with spontaneous of cancer include infection, febrile episodes, and hormonal influences.

-

•

This case report documents spontaneous resolution of pancreatic cancer after a myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Case report, Pancreatic carcinoma, Spontaneous regression, Fever, Infection, Leukocytes

Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous regression of cancer is defined as the partial or complete disappearance of malignant disease without treatment, or in the presence of therapy that is deemed inadequate to exert an influence on malignant disease, as composed by Tilden Everson and Warren Cole in the 1960s. It has been a topic of major interest in the field of medical and surgical oncology. It is poorly understood and scantily documented. Factors associated and postulated pathogeneses are at best, hypothetical.

Presentation of case

We report a case of spontaneous resolution of a head of pancreas carcinoma in a 77-year-old gentleman after a myocardial infarction event delayed planned surgery.

Discussion

A literature review of previously reported cases of spontaneous regression of pancreatic cancer was performed. The possible predisposing factors to spontaneous regression of pancreatic and other forms of malignancies was reviewed.

Conclusion

This is a novel case of spontaneous regression of pancreatic carcinoma after an episode of myocardial infarction. The pathophysiology to spontaneous resolution of cancer is not well understood, may be multifactorial and requires further study

1. Introduction

Spontaneous regression of cancer is an extremely rare occurrence with reports estimating a rate of once in every 60,000–100,000 victims of cancer [1]. Certain cancers have seen a higher rate of regression such as in malignant melanomas and infant neuroblastomas where rates of spontaneous regression have been estimated at 1 in 400 and 1 in 6 respectively [2]. Cancers of intra-abdominal organs exhibit a much lower rate of spontaneous regression. Spontaneous regression of pancreatic cancer is among the rarest of occurrences with only 5 previous cases reported to date [3], [4].

Frequent and well-known associations of spontaneous cancer regression involve concomitant infection [5], [6], [7], [8], febrile episodes [5] and hormonal influences [9]. This report documents a case of spontaneous regression of head of pancreas carcinoma in a patient who developed an interval episode of non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). This case report was written in line with the SCARE checklist [10].

2. Case report

A 77-year-old gentleman presented in January 2015 with a 2-week history of jaundice, pruritus, bruising, tea-coloured urine, unintentional weight loss of 13 kg over the past year and a loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed scleral icterus and a right hypochondriac mass palpable approximately 2–3 cm inferior to the left costal margin.

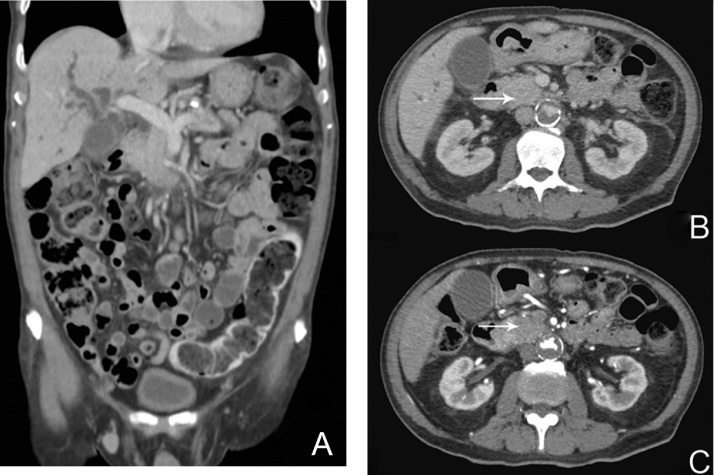

Liver function test (LFT) revealed elevated total serum bilirubin 131 μmol/l, alanine transaminase (ALT) 300U/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 217 U/L and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 964 U/L. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was elevated at 227 U/ml. Computer Tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (CTAP) revealed marked dilatation of the intrahepatic and common bile ducts with an abrupt cutoff proximal to a 4.0 × 4.4 cm ill-defined hypovascular mass in the pancreatic head (Fig. 1A–C – white arrows). Based on clinical presentation and radiological findings, a multidisciplinary tumor conference consensus was that this as a resectable head of pancreas (HOP) adenocarcinoma. The patient was counselled for endoscopic ultrasound and biopsy but opted for pancreaticoduodenectomy upfront.

Fig. 1.

A: Computer Tomographic scan (coronal plane) of the abdomen at time of diagnosis. B/C: Fig. 1B and 1C shows the venous and arterial phases of the Computer Tomographic scan (axial plane) of the abdomen at time of diagnosis respectively. White arrows demarcate the 4.0 × 4.4 cm ill-defined hypovascular mass in the pancreatic head.

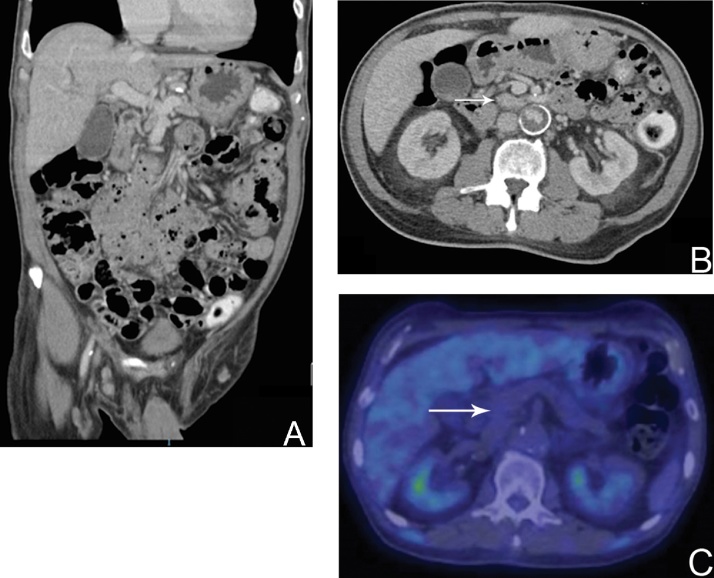

Pre-operative anaesthetic evaluation revealed a carotid bruit. Carotid artery duplex scan revealed 70% stenosis bilaterally for which he underwent a left carotid endarterectomy, as recommended by the anesthetist and vascular surgeon. Unfortunately, post-procedure, he suffered an episode of non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) complicated by pulmonary edema. The pancreaticoduodenectomy was thus postponed and the patient discharged 3 weeks later. The pancreaticoduodenectomy was scheduled to take place a few weeks post-discharge. However, in the span of 4 weeks between the diagnosis of the HOP carcinoma and hospital discharge, the patient’s LFT unexpectedly improved (Table 1), and eventually normalized without biliary decompression over the next 4 months. His CA19-9 levels were down-trending and normalized within the next 2 months. He regained his appetite and gained weight. A CTAP scan 4 months after initial diagnosis revealed that the intrahepatic and common bile duct biliary dilatation previously observed had resolved and the previously noted HOP tumor was no longer identified (Fig. 2A and B). The Position Emission Tomography-Computer Tomography (PET-CT) scan revealed an absence of any appreciable fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid focus in the pancreas (Fig. 2C). These findings were reviewed and agreed upon at Hepatopancreatobiliary multidisciplinary tumor conference.

Table 1.

LFT trending during the 4 weeks between diagnosis of HOP carcinoma and hospital discharge.

| Date | 5/1/15 | 8/1/15 | 9/1/15 | 12/1/15 | 15/1/15 | 18/1/15 | 19/1/15 | 22/1/15 | 23/1/15 | 24/1/15 | 25/2/15 | 26/1/15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin (g/dL) | 32 | 31 | 23 | 21 | 24 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| Bilirubin (umol/L) | 131 | 148 | 178 | 154 | 171 | 91 | 79 | 58 | 60 | 56 | 43 | 41 |

| AST (U/ml) | 217 | 285 | 332 | 310 | 476 | 270 | 140 | 43 | 65 | 86 | 63 | 42 |

| ALT (U/ml) | 300 | 290 | 276 | 247 | 343 | 250 | 164 | 58 | 56 | 45 | 41 | 38 |

| ALP (U/ml) | 964 | 1128 | 1009 | 1099 | 1365 | 1090 | 989 | 605 | 611 | 485 | 417 | 237 |

| GGT (U/ml) | Not performed | Not performed | 849 | 697 | 865 | 760 | 700 | 406 | 432 | 282 |

Fig. 2.

A: Computer Tomographic scan (coronal plane) of the abdomen 4 months after time of diagnosis. B: Venous phase of Computer Tomographic scan (axial plane) of the abdomen 4 months after time of diagnosis. White arrow demarcates region of previously identified hypovascular pancreatic head mass. C: Position Emission Tomography scan with absence of any appreciable fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid focus in the pancreas.

In view of the above events, and after discussion with the patient, pancreaticoduodenectomy was held off. Two consecutive CTAP scans 4 months and 10 months from the initial positive scan were normal. Since January 2015, he has been on 6-monthly follow up with LFT and CA19-9 blood tests each time which have all been normal. His last follow-up was in May 2016 with normal blood test results.

3. Discussion

Also known as ‘Saint Peregrine tumor’ [11], spontaneously regressing cancers occur in only approximately 0.00001–0.000016% of all types of cancers [7], but this phenomenon has been extensively reported in the medical literature as early as 1742 [11]. It is reported that almost all types of malignant tumors have been shown to regress spontaneously. This includes both the primary tumor and metastases, with the latter occurring more frequently [12]. Spontaneous regression of pancreatic cancer is especially rare as compared to other types of malignancies such as melanomas, infant neuroblastomas and testicular germ cell tumors that regress with a known and predictable frequency [2], [12].

To date, there have only been 4 other reports of spontaneous regression of pancreatic carcinoma (Table 2) [3], [4]. One case documents a lady presenting with jaundice and right hypochondriac pain. She was diagnosed with cholangitis secondary to head of pancreas carcinoma on exploratory laparotomy and biopsy. The cancer was deemed inoperable and she was discharged to home care. She remained in good health and died 7 years later from a pulmonary embolism. An autopsy performed revealed no trace of any pancreatic tumor [3], [4]. Another case involves a gentleman presenting with a 3-month history of weight loss and anorexia, with pancreatic adenocarcinoma diagnosed on computer tomography (CT)-guided biopsy. The tumor was considered inoperable and the patient started on chemotherapy. Repeated CT scans showed increasing tumor size and treatment was considered to a failure. Six months later, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy for a perforated duodenal ulcer with peritonitis. This was complicated post-operatively by recurrent bouts of pneumonia. Two months post-operatively, the patient was gaining weight and repeat CA19-9 levels had decreased to within normal ranges. A PET scan confirmed the regression of pancreatic tumor [4].

Table 2.

Literature review of all 4 case reports of spontaneous resolution of pancreatic carcinoma and their initial presentation, method of diagnosis, interim events and eventual outcome.

| No. | Author/Year | Gender/Age | Initial presentation | Method of diagnosis | Diagnosis | Interim event | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shapiro SL/[3] | Unknown/Unknown | Jaundice | Exploratory laparotomy with biopsy of pancreatic mass | Inoperable pancreatic carcinoma | None (remained in good health) | Passed away 7½ years later from pulmonary embolism |

| Abdominal pain | Autopsy failed to find any trace of cancer | ||||||

| Nausea | |||||||

| Chills | |||||||

| High fever | |||||||

| 2 | Cann et. al./[4] | Male/Unknown | Abdominal pain | Exploratory laparotomy with biopsy of pancreatic mass | Pancreatic head carcinoma extending into liver with involved lymph nodes | None | Examined 6 months later and remained asymptomatic |

| Diarrhea | |||||||

| 3 | Cann et. al./[4] | Male/21 | Jaundice | Exploratory surgery for unrelated event (biliary peritonitis secondary to liver biopsy) with biopsy of incidental pancreatic mass | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Whipple’s procedure undertaken but abandoned intra-operatively. Patient made slow recovery at home. | Examined 12 years later and remained asymptomatic |

| Malaise | |||||||

| Fever | |||||||

| Post-liver biopsy biliary peritonitis(hypotension, tachycardia, abdominal pain) | |||||||

| 4 | Cann et. al./[4] | Male/50 | Weight loss | Abdominal ultrasound | Pancreatic body adenocarcinoma | Tumor considered inoperable, 6-month course of chemotherapy administered. 6-month follow-up revealed raised CA19-9, identical CTAP findings, progressive loss of weight and appetite. Chemotherapeutic management was considered a failure. | 3-month follow-up revealed spontaneous tumor resolution with normal CA19-9 levels and negative PET scan. |

| Anorexia | CA19-9 | Patient developed perforated duodenal ulcer with peritonitis and was taken to theatre. Post-operative recovery complicated by recurrent pneumonia and fever and patient was only discharged 1 month later. | 8-month follow-up revealed elevated CA19-9 and a confirmed relapse on PET scan. Patient passed away 2 months later | ||||

| CTAP | |||||||

| CT guided biopsy | |||||||

Infection has been a well-documented correlating factor with spontaneous regression of all types of cancers. Studies have proven that the development of empyema after lung surgery in patients with lung carcinoma increased survivability by 50% [13]. Other examples have cited cases of patients undergoing palliative gastroenterostomy for incurable gastric carcinoma with post-operative anastomotic leak and peritonitis, having spontaneous resolution of the primary cancer after the infection was treated [14]. Significantly, Coley, a surgeon at Memorial Hospital in New York prepared ‘Coley’s toxin’ which comprised an extract from killed Streptococcus pyogenes and gram-negative Serratia marcescens bacteria specifically for this experimental purpose [7], [8], [11], [15]. Coley successfully used this vaccine in treating a man bedridden with inoperable sarcoma involving the abdominal wall, pelvis and bladder. The sarcoma regressed completely, and the patient passed away 26 years later from a myocardial infarction [11]. Wiemann and Starnes subsequently injected this preparation into tumors of patients with advanced sarcomas, with a noted increase in 5-year survival rate of 44% [15], [16]. These studies have, unfortunately, been largely overlooked due to the advent of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The pathophysiology behind this is largely attributed to the dual role of leukocytes in the immune system. While primarily involved in defense against infective pathogens, leukocytes also play an important role in growth factor production, angiogenesis and tissue remodeling [5], [17]. As such, when a concomitant infection results in intra-tumoral leukocytes re-activating their immune functions, tumor regression follows [5]. It has been suggested that perhaps the decrease in number of reported cases of spontaneous cancer regression can be attributed to the advent of aseptic techniques, use of prophylactic antibiotics, early antibiotic intervention with infections and the presence of immunosuppressive chemotherapy [4].

Fever is another well-documented correlating factor with spontaneous regression of cancer. According to a trial by Nauts and McLaren, when the ‘Coley’s toxin’ preparation was used in the treatment of surgically inoperable cancers, the efficacy was higher in patients who suffered from interim high fevers (>38 °C) [4], [16], [18]. It has been postulated that cancer cells are less resistant to increased body temperature than normal cells [16].

Other factors associated with spontaneous regression of cancer are allergenic and hormonal influences. The latter is especially prevalent in carcinoma of the lung with concomitant hypothyroidism [19] and in thymomas of the mediastinum with exogenous glucocorticoid administration [12]. Recent genomic studies have identified oncosuppressor genes such as a transcriptional gene that induces apoptotic cell death in the region of chromosome 1p362. The presence of this gene has been shown to be predictive of spontaneous cancer regression; particularly in breast cancer. [12]

Myocardial infarctions are commonly accompanied by fever and leukocytosis during and after the acute episode. This could perhaps provide a plausible pathogenesis with regards to the spontaneous regression of our patients’ pancreatic head tumor. However, given the extensive literature correlating infection, fever and spontaneous cancer regression, this case serves to highlight that viewing cancer regression as an outcome of a single correlating entity may be unwise, and that the pathophysiology is likely to be multifactorial.

4. Conclusion

Spontaneous regression of cancer is an extremely rare occurrence, especially in pancreatic carcinomas. This is a novel case of spontaneous regression of pancreatic carcinoma after an episode of myocardial infarction. Based on the literature implicating correlating infection, febrile episodes and other immunological events with spontaneous cancer regression, the pathophysiology is not well understood and is most likely multifactorial. More studies will need to be done to further investigate and better understand this interesting phenomenon.

Conflicts of interest

Authors of this manuscript have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias our work.

Funding

There was no financial funding or sponsors involved in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been exempted by the institution in which this manuscript was written and submitted from. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request. There is no ethical issue in this paper and all identifying names or identities have been omitted from the manuscript.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request. There is no ethical issue in this paper and all identifying names or identities have been omitted from the manuscript. Ethical approval has been exempted by the institution as there are no patient identifiers or names included.

Author contribution

The author Ken Min Chin has made substantial contribution in terms of acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article and writing the final paper. The authors Chung Yip Chan and Ser Yee Lee are in charge of the clinical care of the patient and have made substantial contribution in terms of analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, writing the final paper and revising the final manuscript for critically important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Guarantor

The guarantor for this manuscript will be Dr. Lee Ser Yee, the corresponding author.

Footnotes

All work was performed at Singapore General Hospital, 1 Hospital Drive, 169608, Singapore.

References

- 1.Boyd W. CC Thomas; 1966. The Spontaneous Regression of Cancer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koop C.E., Kiesewetter W.B., Horn R.C. Neuroblastoma in childhood; survival after major surgical insult to the tumor. Surgery. 1955;38(July (1)):272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro S.L. Spontaneous regression of cancer. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1967;46(October (10)):1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cann S.A., Gunn H.D., Van Netten J.P., Van Netten C. Spontaneous regression of pancreatic cancer. Case Rep. Clin. Pract. Rev. 2004;9(July):293–296. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cann S.H., Van Netten J.P., Van Netten C. Dr William Coley and tumour regression: a place in history or in the future. Postgrad. Med. J. 2003;79(December (938)):672–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coley W.B., I The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas. Ann. Surg. 1893 Jul;1(18):68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coley W.B., II Contribution to the knowledge of sarcoma. Ann. Surg. 1891;14(September (3)):199. doi: 10.1097/00000658-189112000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy E.F. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop. J. 2006;26:154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nauts H.C. Cancer Research Institute; 1980. The Beneficial Effects of Bacterial Infections on Host Resistance to Cancer End Results in 449 Cases: A Study and Abstracts of Reports in the World Medical Literature (1775–1980) and Personal Communications. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jessy T. Immunity over inability: the spontaneous regression of cancer. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2011;2(January (1)):43. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basso Ricci S., CERChIARI U.G. Spontaneous regression of malignant tumors: Importance of the immune system and other factors. Oncol. Lett. 2010;1(November 1 (6)):941–946. doi: 10.3892/ol.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagorsen D., Marincola F.M., Kaiser H.E. Bacteria-related spontaneous and therapeutic remission of human malignancies. In vivo (Athens, Greece) 2001;16(December (6)):551–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handley W.S. A lecture on the natural cure of cancer. Br. Med. J. 1909;1(March (2514)):582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2514.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiemann B., Starnes C.O. Coley's toxins, tumor necrosis factor and cancer research: a historical perspective. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994;64(December (3)):529–564. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauts H.C., McLaren J.R. Springer; US: 1990. Coley Toxins—the First Century. In Consensus on Hyperthermia for the 1990; pp. 483–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rüegg C. Leukocytes, inflammation, and angiogenesis in cancer: fatal attractions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;80(October (4)):682–684. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruckdeschel J.C., Codish S.D., Stranahan A., McKneally M.F. Postoperative empyema improves survival in lung cancer: documentation and analysis of a natural experiment. N. Engl. J. Med. 1972;287(November (20)):1013–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197211162872004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hercbergs A. Spontaneous remission of cancer–a thyroid hormone dependent phenomenon? Anticancer Res. 1998;19(December (6A)):4839–4844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;31(34 (October)):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]