Summary

Background

Hyaluronic Acid (HA) has been already approved by Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for osteoarthritis (OA), while its use in the treatment of tendinopathy is still debated. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of two different HA on human rotator cuff tendon derived cells in terms of cell viability, proliferation and apoptosis.

Methods

An in vitro model was developed on human tendon derived cells from rotator cuff tears to study the effects of two different HA preparations: Sinovial HL® (High-Low molecular weight) (MW: 80–100 kDa) and KDa Sinovial Forte SF (MW: 800–1200), at various concentrations. Tendon derived cells morphology was evaluated after 0, 7 and 14 d of culture. Viability and proliferation were analyzed after 0, 24, and 48 h of culture and apoptosis occurrence was assessed after 24 h of culture.

Results

All the HAPs tested here increased viability and proliferation, in a dose-dependent manner and they reduced apoptosis at early stages (24 h) compared to control cells (without HAPs).

Conclusions

HAPs enhanced viability and proliferation and counteracted apoptosis in tendon derived cells.

Keywords: hyaluronic acid, tendinopathy, human tendon derived cells, rotator cuff tendons, shoulder

Background

Non-traumatic rotator cuff tear is the most common shoulder joint disease and it has age-associated incidence, since it is favored by the co-presence of metabolic diseases such as diabetes, thyroid disorders and hypercholesterolemia1–4. Conservative treatment of tendinopathies has been increasingly supported by scientific evidence over the last twenty years5. Despite decades of study of HA in the conservative treatment of osteoarthritis6, poor evidence is present in the literature about the clinical indication for this drug towards tendinopathies7. During tendinopathy and tendon acute rupture, a higher incidence of tenocyte apoptosis occurrence and decreased collagen synthesis has been reported8. The failure of the healing response may occur in genetically-predisposed patients, decreasing the resistance of tendon structures to mechanical load, resulting eventually in tendinopathy, or a tendon tear4,9,10.

Hyaluronic acid (HA) (or “hyaluronan”, or “sodium hyaluronate preparation”) is a high molecular weight glycosaminiglycan, consisting on the repetition of a disaccharide unit composed by N-acetyl-glucosamine and a β-glucuronic acid11. Its most important physicchemical properties are the capacity of retaining water with a very high hydration ratio, and its visco-elasticity. However these two properties are interdependent. Changes in HA concentration within the extracellular matrix modulates a variety of cellular functions, such as cell migration12,13, adhesion14,15 and proliferation16–18. Several important medical applications of HA have been discovered for joints degeneration7. Additionally, high local concentration of HA causes endogenous growth factors release and stimulates cell-cell interaction, resulting in a faster cell proliferation rate during early stages of in vitro culture. Additional effects reported in clinical animal studies have been related to an accelerated healing process in tendons after repair and a decreased scar formation within the tendons itself. There has been a lack of specific studies on human shoulder derived cells. Manystudies have been limited because the exact phenotype of the tendon derive cells is still difficult to display. Moreover, the pattern of their gene expression is consistent with the presence of mixed populations19. Clinical studies on patients suffering of rotator cuff disease ranging from tendinopathy derived from rotator cuff tears detected a positive influence on the reduction of pain and an improved function with no consistent side-effects recorded. Our previous data showed that different hyaluronic acid preparations induced increase of cell metabolism, decrease of apoptosis of tendon derived cells collagen type I protein secretion in dose-dependent manner but not related to the molecular weight20. These results confirmed a physiological role of HA in the homeostasis of tendons and they have implications among regenerative medicine. Despite three different molecular weights of HA were tested here, more HAPs and different concentrations need to be further tested in the same experimental conditions to confirm which should have the best in vitro positive effects.

In this study, the effect of two HAPs, which differ by molecular weight, was evaluated, and viability, cell proliferation and apoptosis occurrence on human rotator cuff tendon tears derived cells were analyzed.

Materials and methods

All the procedures described in this investigation were approved by the Ethical Committee of Rome Tor Vergata University. All the patients gave written informed consent to be included in the present study. Tendon samples were harvested from healthy area close to the degenerative supraspinatus tendons tear region and biopsy specimen were operated arthroscopically for shoulder rotator cuff repair in 10 patients, with a mean age of 63,6 ± 6,9 years. Trauma history, heavy smoking habit or systemic conditions such as thyroid disorders, diabetes, gynecological condition, neoplasia, rheumatic diseases, and any previous or concomitant rotator cuff disease were considered exclusion criteria.

Tendon cell cultures

Primary human tendon derived cell cultures were established as previously described21. In brief, cells were isolated from tissue sample by washing several times with phosphate buffered saline Dulbecco’s W/O Ca and Mg (PBS) + 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Small pieces of fresh tendon isolated were carefully dissected and mechanically disaggregated with the aid of fine watchmaker forceps to maximize the interface between tissue and medium. Finally, tendons were immediately placed on Petri dishes of 60 mm of diameter (Greiner CELLSTAR dish, Sigma- Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), containing 5 mL of α-MEM supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated foetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Invitrogen, Life Technologies) at 37° C in 5% CO2 and air with a change medium every 2–3 d. Tenocytes were then harvested by StemPro Accutase (Life technologies Carlsbad, CA, USA) and centrifugated at 1,500 rpm for 5 min when the cells migrated out of tendon pieces and reached 60–80% of confluence (19 day). Collected tendon derived cells were immediately used for culture to avoid phenotype drift with further in vitro passages22. The phenotype of the tendon derived cells had not demonstrated significant drift as evidenced by the gene expression pattern by assessing the expression of gene for scleraxis and genes for collagens α1(I), α2(I) and α1(III) in real-time PCR assays with specific primers (data not shown).

Tenocyte viability

In vitro viability was determined by the trypan blue exclusion assay. Tendon derived cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (1×104 cells/well) (Greiner CELLSTAR dish, Sigma-Aldrich) in triplicates in 1 ml of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Cells were cultured as previous described21. Briefly, after 24 h, cultured cells were exposed to two different hyaluronic acid: Sinovial Forte (F) MW 800–1200 KDa, Sinovial HL (High-Low molecular weight) ® MW 1100–1400 KDa, the features of which are listed in Table I. Three different doses of Sinovial Forte or Sinovial HL (250 μg/ml, 500 μg/ml and 1000 μg/ml) were administrated. HAPs were dissolved in the same culture media used for the entire experiments (α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS) and the Ph was adjusted to 7.0. Cells without treatments were used as control. All the cells (HAPs-treated and untreated) were cultured in 1 ml of medium. After 0, 24, and 48 h tenocytes were detached, collected and counted (Nikon Instruments INC., Melville, NY, USA) in the Burker chamber with vital dye Trypan Blue (Stem Cells Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) to evaluate cell viability.

Table I.

Features of hyaluronic acids preparations tested.

| Commercial Name | Sinovial® HL, 3.2% | Sinovial Forte® 1.6% |

|---|---|---|

| Active Substance | Linear Sodium Hyaluronate | Linear Sodium Hyaluronate |

| Molecular Weight | High 1100–1400 kDa, Low 80–100 kDa | 800–1200 kDa |

| Source | Bacterial Fermentation | Bacterial Fermentation |

| Doses Tested | 250 μg/ml 500 μg/ml 1000 μg/ml | 250 μg/ml 500 μg/ml 1000 μg/ml |

| Manufacturer | IBSA Farmaceutici ItaliaSrl, Lodi, Italy |

Cell proliferation assay with CFSE staining

The proliferation rate of human tenocytes was determined by monitoring the decrease of green fluorescence in flow cytometry by means of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (CellTrace™ Cell Proliferation Kits, Invitrogen, CA, USA). Cells (2×104 tenocytes) were cultured in T-25 flasks (VWR International PBI, MI, Italy) with 5ml α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After 24 h cells were labeled with 2 μM CFSE for 20 min at room temperature. The CFSE readily diffuses into cells and binds covalently to intracellular amines. Five volumes of cold completed α-MEM medium were then added to stop the staining reaction. The cells were then washed three times with PBS to remove the excess of the staining. The stained tenocytes were stimulated as described above to monitor cell proliferation. After 0, 48 and 72 h samples were detached and analyzed by a CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) with a FL1 (FITC) detector in a linear mode. The CFSE monitors the distinct generations of the proliferating cells by dye dilution resulting in a decrease of green fluorescence. Live cells are covalently labeled with a very bright and stable dye, while every generation of cells appears as a different peak of decreasing fluorescent intensity on a flow cytometric histogram. The percentage of apoptotic and dead cells were quantified using Annexin V (BD Pharmingen). The ModFit LT software (Verity Software House, ME, USA) was used to quantify the proliferation indexes and to visualize proliferating cells on statistical histograms.

Measurement of apoptosis and necrosis by FACS analyses

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used as an inducer of apoptosis as previously described23. The tendon derived cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (2×104 cells/well) with 4 ml of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After 24 h, the medium was removed and the cultured cells were treated with H2O2 (final concentration 2mM) in complete α-MEM with or without Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte (1000 μg/ml) for a further 24 h. A negative control was prepared by incubating cells in the absence of the inducing agent and HAPs. The Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (eBioscience, USA) was used to detect apoptosis by flow cytometry. Cells were harvested and stained supravitally according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, this product detects the externalization of phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cell membranes using a recombinant Annexin V FITC-conjugated antibody, and displays dead cells using the Propidium Iodide (PI). After exposing cells with the both probes, apoptotic cells show green fluorescence, dead cells show red fluorescence and viable cells result unstained. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was carried out using a CytoFlex cytometer with the FL1 and FL3 detectors in a log mode and analyzed using the CytoFlexanalysis software (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data are typical results from a minimum of three independent replicated experiments and they are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparison of individual treatment was conducted using the Student’s t test. Statistical significance in comparison with the corresponding control values was indicated by *p<0.05 versus control.

Results

Tendon derived cells viability

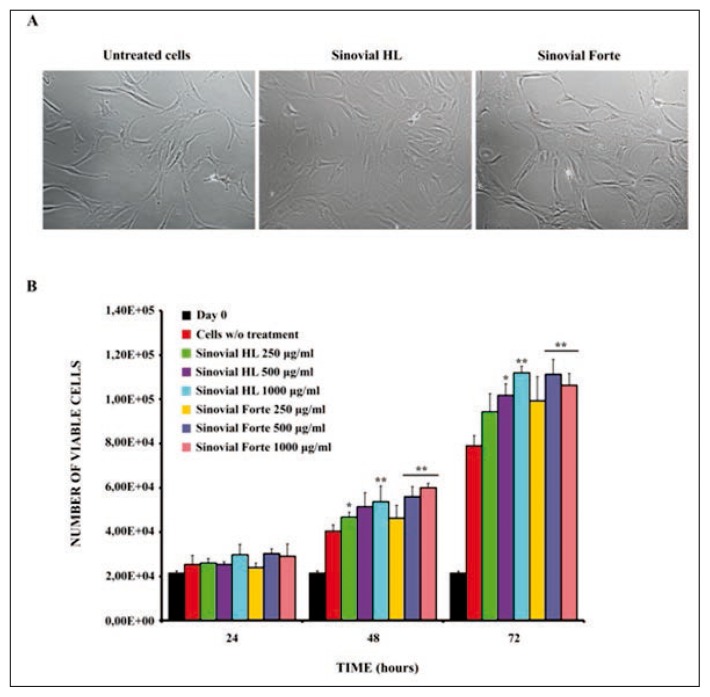

Tendon derived cell morphology was evaluated under a light microscope at 0, 7 and 14 d. The cells maintained their normal, bipolar, spindle shape and cell processes, during the whole study period for each of the sets of culture conditions; cellular morphology remained unaltered for up to 14 d in all the experimental groups (Fig. 1 A). To examine the temporal nature of HAPs-induced cytotoxicity, the Trypan Blue exclusion test was performed in order to monitor cell viability for up to 72 h after exposure to different concentrations of HAPs: 250 μg/ml, 500 μg/ml and 1000 μg/ml. As shown in Figure 1 B, the number of viable cells increased significantly in a time- and concentration-dependent manner with respect to the control sample.

Figure 1 A, B.

Effects of Sinovial HL® and Sinovial Forte® on cell morphology and viability. Tendon derived cells were treated with different concentrations of Sinovial HL® and Sinovial Forte® from 0 to 72 h. A) After treatment for 14 d the morphology of the cells treated with all the HAs was photographed (1000ug/ml). Magnification, ×100. B) Trypan blue exclusion test for cell viability of tendon derived cell after 24, 48 and 72 hours (hrs) of treatment with Sinovial HL® and Sinovial Forte®. HAs increased cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner and with regard to time. Significant differences were observed from control according to the Student’s t-test. All the experiments were repeated in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean ± SD *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with untreated cells.

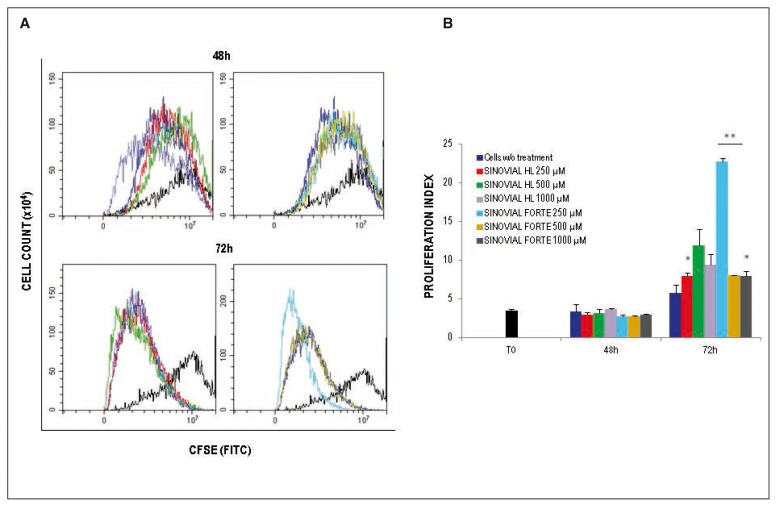

Cell proliferation index was enhanced in Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte stimulated tenocytes

To assess cell proliferation, cells were labeled with the vital dye CFSE. This dye is retained in the cytoplasm and it is diluted out after each cell division, and thus allows tracking cell divisions in cultured cells by flow cytometry. Wherefore, isolated human tenocytes were stained with the fluorescent dye and cultured in the presence of three different doses Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte: 250 μg/ml, 500 μg/ml and 1000 μg/ml. Untreated cells were used as control. All HAPs induced proliferation in all the experimental conditions, and the majority of cells underwent multiple cell divisions in the 72h test period. Sinovial HL at 250 μg/ml significantly induce proliferation (Fig. 2 A, B); notably, Sinovial Forte induced cell proliferation with all the concentrations here tested, particularly 250 μg/ml was the most significant concentration after 72 h (Fig. 2 A, B).

Figure 2 A, B.

Cell tracking assay with CFSE CellTrace™. Tenocytes derived from tendon were stained with CFSE Cell- Trace™ on day 0. A) Fluorescence intensity was measured by CytoFlex flow cytometer in the FL1 channel at 0, 48 h, and 72h. B) Histograms show the mean (± SD) of the proliferation index of CFSE of one experiment out of three. Standard deviations are shown (*p<0,05; **p<0,01).

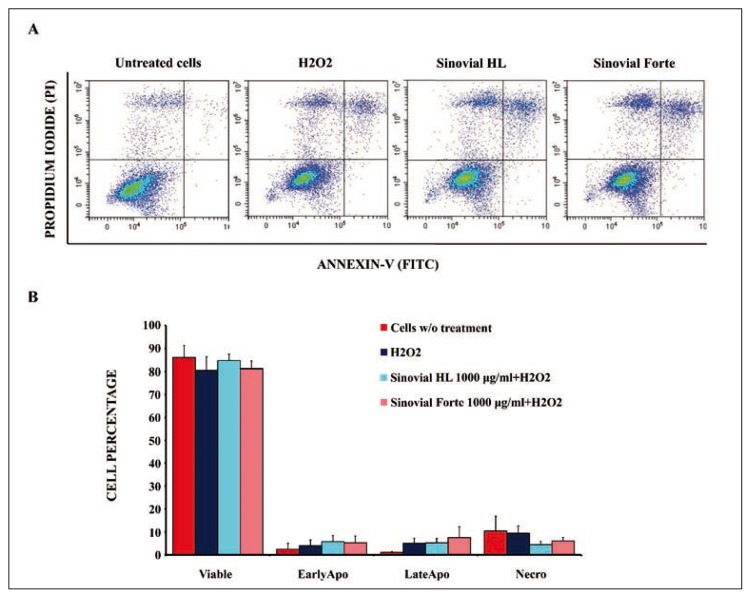

Apoptosis induction

To verify whether or not has counteracted apoptosis occurrence in tendon derived cells, the Annexin V assay was performed. H2O2 was used here as an apoptotic inducer for 24 h. Concurrently, tendon derived cells were separately exposed (or not, as for the untreated sample) to Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte (1000 μg/ml). Then cells were simultaneously stained with FITC-Annexin V (green fluorescence) and the non-vital dye, Propidium Iodide (red fluorescence), allowing through a bivariate analysis, the discrimination between intact cells (Annexix V− PI−), early apoptotic (Annexix V+ PI−) cells, and late apoptotic (Annexix V+ PI+) and necrotic cells (Annexix V− PI+) (Fig. 3 A). The treatment of tendon derived cells with 1000 μg/ml Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte caused an undetectable decrease in the percentage of apoptotic population, as clearly shown in Figure 3 B. Moreover, the percentage of viable cells, after a 24 h exposure to Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte increased, even if lower compared to the control (84,58%±2,9%, 81,19%±3,2% and 85,99%±5,2% respectively) (Annexix V−, PI−, bottom left quadrant) (Fig. 3 A, Tab. II). To note, the percentage of viable cells with Sinovial HL was higher compared to Sinovial Forte at 1000 μg/ml (Fig. 3 B, Tab. II).

Figure 3 A, B.

The apoptosis occurrence in tendon derived cells. The apoptosis was induced with H2O2 and cells were treated with Sinovial HL® and Sinovial Forte® (1000 ug/ml). Apoptosis rate of cells in each sample were detected in a population of 10,000 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. A) The percentage of apoptotic cells in Sinovial HL® and Sinovial Forte® do not decrease compared to the control sample (without HA). Flow charts: upper left quadrant Annexin V-negative and PI-positive cells indicate necrotic cells; upper right quadrant, Annexin V and PI-positive cells represent late apoptotic cells. lower left quadrant, Annexin V-negative and PI-negative cells indicate viable cells; lower right quadrant, Annexin V positive and PI-negative cells represent early apoptotic cells. B) % of cells population of viable cells, early apoptotic cells, late apoptotic cells and necrotic cells. Graph showing the average % of results obtained in 3 independent experiment. No significant differences were detected (mean ± S.D.; n=3).

Table II.

Summary of results.

| APOPTOSIS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Cells | Live Cells | Early | Late | Necro |

| Proliferant control | 85,99%±5,2% | 2,44%±2,6% | 1,15%±0,3% | 10,42%±6,4% |

| Apoptotic control | 80,53%±5,8% | 4,01%±2,5% | 5,01%±2,2% | 9,45%±3,7% |

| Sinovial® HL 1000 g/ml | 84,53%±2,9% | 5,75%±2,7% | 5,21%±1,9% | 4,45%±1,5% |

| Sinovial Forte® 1000 g/ml | 81,19%±3,2% | 5,26%±3% | 7,56%±4,7% | 6%±1,6% |

Discussion

These results suggest a role of HA on tendon derived cells proliferation. It was highlighted that Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte regulate cell proliferation of tendon derived cells. All HAPs increased cell-proliferation mostly after 72 h of exposure. HA modulates a number of biological process including cell apoptosis. The results show a reduction of the apoptotic population when the tendon derived cells were exposed to the Sinovial HL or the Sinovial Forte.

Considering the results of this study, the two different molecular weights of HAPs tested here seemed to do not exert relevant effects on tendon derived cells in vitro, while it is clear the fundamental importance of the loading concentrations and of the timing of exposure. HL is featured by a bimodal molecular weight profile distribution, with a high and low molecular weight fractions combined. SF is featured by the same high molecular weight fraction of HL but is devoid of the low molecular weight fraction. Despite the double concentration, within HL the extra content of HA is of much lower molecular weight23. Cell viability and proliferation rate increased in all the culture conditions over time. However, SF boosted cell proliferation and viability at 72 h of culture more significantly. This stimulation effect was attributed to the presence of the high molecular weight fraction. Translating these considerations in the clinical practice, HA are effective on the human tenocytes of rotator cuff, with no essential differences among Sinovial HL or Sinovial Forte commercially available. There are many biological questions that remain to be answered and translational factors to solve. Although, this in vitro model shows some role played by HAs on tendon derived cells, the study has some limitations. First of all, it is plausible to assume that these results cannot be generalized for other cells derived from other sources but tendons. Furthermore the in vitro environment, rich of nutrients and oxygen, is very different from the pathological environment. Finally, there is an urgent need to widen the knowledge on the effects of HAs on the main proteins of the extracellular matrix of tendons.

However, in a clinical view, translating basic knowledge from bench to bedside is still challenging24. Indeed the conclusions are limited by the only in vitro evaluation performed on tendon derived cell cultures. Further investigations are necessary to verify if this effect could also be observed in animal models. Obviously, randomizing control studies on the use of HAs (between low MW HA, high MW HA) in the conservative treatment of tendinopathies and in selected patients with rotator cuff tears is mandatory, in order to understand and clarify the best timing, doses, intervals of injections and, finally, full clinical confirmation of effectiveness.

Conclusion

In conclusion, HAs induce increase of cells viability and cell proliferation, decrease of apoptosis of tendon derived cells in a dose dependent manner but not related to the molecular weight. Taken together, these results reinforce the physiological role of HAs in the homeostasis of tendons and they have implications for regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by Fondazione PCFF ONLUS.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Oliva F, Osti L, Padulo J, Maffulli N. Epidemiology of the rotator cuff tears: a new incidence related to thyroid disease. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(3):309–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osti L, Rizzello G, Panascì M, et al. Full thickness tears: retaining the cuff. Sports Med Arthosc. 2011;19(4) doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e31823940da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliva F, Berardi AC, Misiti S, Maffulli N. Thyroid hormones and tendon: current views and future perspectives. Concise review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3(3):201–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klatte-Schulz F, Pauly S, Scheibel M, et al. Influence of age on the cell biological characteristics and the stimulation potential of male human tenocyte-like cells. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;24:74–89. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v024a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loppini M, Maffulli N. Conservative management of tendinopathy: an evidence-based approach. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;1(4):134–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, et al. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthitis of the knee: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;157(3):180–191. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abate M, Schiavone C, Salini V. The use of hyaluronic acid after tendon surgery and in tendinopathies. Biomed Res Int. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/783632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giai Via A, De Cupis M, Spoliti M, Oliva F. Clinical and biological aspects of rotator cuff tears. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;3(4):359. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.2.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan J, Wang MX, Murrell GA. Cell death and tendinopathy. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(4):693–701. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(03)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benson RT, McDonnell SM, Knowles HJ, et al. Tendinopathy and tears of the rotator cuff are associated with hypoxia and apoptosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(3):448–453. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B3.23074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer K. Chemical structure of hyaluronic acid. Fed Proc. 1958;17(4):1075–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melrose J, Numata Y, Ghosh P. Biotinylated hyaluronan: a versatile and highly sensitive probe capable of detecting nanogram levels of hyaluronan binding proteins (hyaladherins) on electroblots by a novel affinity detection procedure. Electrophoresis. 1996;17(1):205. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen WY, Grant ME, Schor AM, Schor SL. Differences between adult and fetal fibroblasts in the regulation of hyaluronate synthesis: correlation with migratory activity. J Cell Sci. 1989;94(Pt 3):577–584. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein ES, Asculai SS, Ben-Ari GY. Effects of hyaluronic acid on fibroblast behavior in peritoneal injury. J Surg Res. 1996;61(2):473–476. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall CL, Wang C, Lange LA, Turley EA. Hyaluronan and the hyaluronan receptor RHAMM promote focal adhesion turnover and transient tyrosine kinase activity. J Cell Biol. 1994;126(2):575–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiig M, Abrahamsson SO, Lundborg G. Effects of hyaluronan on cell proliferation and collagen synthesis: a study of rabbit flexor tendons in vitro. J Hand Surg Am. 1996;21(4):599–604. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard E, Hornebeck W, Robert L. Effect of hyaluronan on the elastase-type activity of human skin fibroblasts. Cell Biol Int. 1994;18(10):967–971. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1994.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matuoka K, Namba M, Mitsui Y. Hyaluronate synthetase inhibition by normal and transformed human fibroblasts during growth reduction. J Cell Biol. 1987;104(4):1105–1115. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean BJ, Snelling SJ, Dakin SG, Murphy RJ, Javaid MK, Carr AJ. Differences in glutamate receptors and inflammatory cell numbers are associated with the resolution of pain in human rotator cuff tendinopathy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:176. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0691-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osti L, Berardocco M, di Giacomo V, Di Bernardo G, Oliva F, Berardi AC. Hyaluronic acid increases tendon derived cell viability and collagen type I expression in vitro: Comparative study of four different Hyaluronic acid preparations by molecular weight. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:284. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0735-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliva F, Berardi AC, Misiti S, et al. Thyroid hormones enhance growth and counteract apoptosis in human tenocytes isolated from rotator cuff tendons. Cell Death and Disease. 2013;4:e705. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao L, Bestwick CS, Bestwick LA, Maffulli N, Aspden RM. Phenotypic drift in human tenocyte culture. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(7):1843–1849. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russo F, D’Este M, Vadalà G, et al. Platelet Rich Plasma and Hyaluronic Acid Blend forthe Treatment of Osteoarthritis: Rheological and Biological Evaluation. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157048. eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal - Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research: 2016 update. MLTJ. 2016;6(1):1–5. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.1.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]