Abstract

Objectives

We examined effects of e-cigarette ad messages and visual cues on outcomes related to combustible cigarette smoking cessation: smoking cessation intention, smoking urges, and immediate smoking behavior.

Methods

US adult smokers (N = 3293) were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk and randomized to condition in a 3 (message: e-cigarette use anywhere, harm reduction, control) × 2 (e-cigarette cue presence or absence) between-subjects experiment. Stimuli were print ads for cigarette-like e-cigarettes (“cigalikes”) that were manipulated for the experimental conditions. We conducted ANOVA and logistic regression analyses to investigate effects of the manipulations.

Results

Message effects on cessation intention and smoking urges were not statistically significant. There was no evidence of cue effects or message × cue interactions across outcomes. Contrary to expectations, e-cigarette use anywhere and harm reduction messages were associated with lower odds of immediate smoking than the control message (AOREUA = 0.75, 95%CI = 0.58, 0.97, p = .026; AORHR = 0.72, 95%CI = 0.55, 0.93, p = .013).

Conclusions

E-cigarette use anywhere and harm reduction messages may encourage smoking cessation, given the observed reduction in immediate smoking. E-cigarette cues may not influence smoking cessation outcomes. Future studies should investigate whether message effects are a result of smokers believing e-cigarettes to be effective cessation aids.

Keywords: e-cigarettes, advertising, cessation, smokers

Electronic cigarette (“e-cigarette”) advertising has increased substantially, with advertising expenditures in the United States (US) increasing from $3.6 million in 2010 to $115.1 million in 2014 (inflation adjusted in 2010 dollars).1,2 Print media is a leading channel for ads, comprising 73% of e-cigarette ad expenditures.3 Exposure to e-cigarette print ads has been high, especially among US young adults (82%).3

Researchers and regulators are increasingly interested in how e-cigarette advertisements affect combustible cigarette smoking and, in particular, combustible cigarette smoking cessation. Although research is ongoing and not yet conclusive, e-cigarettes are generally considered to be less toxic and harmful than combustible cigarettes for an individual user.4–6 Transitioning current cigarette smokers to e-cigarettes exclusively may result in public health gains.7–9 E-cigarette advertising could encourage this transition by steering smokers away from combustible cigarettes and increasing their interest in e-cigarettes.

Alternatively, e-cigarette advertising could inhibit the transition. Combustible cigarette companies have entered the e-cigarette market and have begun to market their e-cigarettes aggressively. MarkTen and Blu, e-cigarette brands owned by combustible cigarette companies, account for most of e-cigarette ad spending and nearly all ad spending in print media.3 Evidence suggests cigarette companies intend for e-cigarettes to complement rather than replace their combustible cigarettes business.8,10 Thus, a concern is that e-cigarette ads might not only promote e-cigarette use but also might cue combustible cigarette smoking, undermining smoking cessation.2

Studies investigating the effect of e-cigarette ads on smoking cessation have yielded mixed results. On the one hand, e-cigarette advertising has stimulated thoughts about quitting smoking11 and the perception that e-cigarettes help with quitting smoking.12 On the other hand, e-cigarette ads have had pro-smoking effects.11,13,14 They have increased cigarette smoking-related thoughts and urges in smokers and have had no effect on quitting self-efficacy or intention.11,14 Experiments with former smokers have demonstrated e-cigarette ads weaken intention and self-efficacy to maintain abstinence from smoking.13,14

In part, these mixed results may be due to the fact that e-cigarette ad stimuli in previous research have featured different e-cigarette messages and images, some of which may encourage smoking cessation and others which may undermine it. Two prominent messages in e-cigarette marketing are that e-cigarettes can be used anywhere and that e-cigarettes are a less harmful alternative to cigarettes.6,15,16 Though the effects of these messages on smoking cessation have not been investigated formally, we predict that they will be distinct. An e-cigarette use anywhere message could elicit lower intentions to quit smoking than a control message because it suggests e-cigarette use does not preclude combustible cigarette use. Such messages could prompt smokers to use e-cigarettes when they cannot smoke, increasing dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes.15,17 In contrast, a harm reduction message reminds viewers that cigarettes are harmful to health; moreover, it promotes e-cigarettes as an alternative, rather than a complement, to smoking. Messages about the negative health consequences of smoking may increase quit intentions and other quitting-related outcomes.18,19 Because harm reduction messages implicitly highlight the negative consequences of smoking, they also may lead to greater quit intentions than a neutral control message.

E-cigarette images, or cues, in ads warrant consideration as well. Combustible cigarette cues, such as smoking-related pictures (eg, people smoking, cigarettes burning in ashtrays)20,21 and video,22–25 have been associated with increased smoking urges among smokers20–23 and lower self-efficacy, attitudes, and intentions to refrain from smoking among former smokers.25 Although e-cigarettes are distinct from combustible cigarettes, some e-cigarettes (“cigalikes”), like MarkTen, are virtually indistinguishable from combustible cigarettes in shape, size, and color.26,27 Ads featuring cigalikes might operate as combustible cigarette ads and undermine smoking cessation. Studies suggest that e-cigarette cues in video ads do indeed undermine smoking cessation by increasing smoking urges and desire28 and stimulating smoking.14 However, whether this effect generalizes to e-cigarette print ads is an open question.

Given that e-cigarette ads often, but not always, pair e-cigarette messages with cues, investigating the interaction of these ad features is critical to understanding how e-cigarette ads might influence smoking cessation. An e-cigarette ad message may have a different effect on cessation, depending on whether or not it is paired with an e-cigarette cue. Combustible cigarette cues divert smokers’ attention and inhibit them from processing ad messages.29 This phenomenon may be more likely to occur with some messages than for others. Combustible cigarette cues have weakened or reversed the effect of anti-smoking arguments on message effectiveness and have stimulated smoking urge in the presence of weak anti-smoking arguments.24,30 If e-cigarette cues operate as combustible cigarette cues and certain e-cigarette ad messages have pro-quitting effects, we would expect a similar message × cue interaction.

In the present study, we assessed the separate and combined effects of e-cigarette ad messages and cues on outcomes related to combustible cigarette smoking cessation. We manipulated real world e-cigarette print ads and analyzed effects in a 3 message (e-cigarette use anywhere, harm reduction, control message) × 2 cue (presence/absence of visual e-cigarette cue) between-subjects experiment.

METHODS

In November 2015, we conducted a randomized controlled experiment through Amazon MechaniEffects of E-cigarette Advertising Messages and Cues on Cessation Outcomes 564 cal Turk (MTurk), an online crowdsourcing service used in social science31,32 and tobacco control research.33,34 We recruited a convenience sample of 3293 adult established cigarette smokers through the platform. This figure approximated our target sample size of 3390, which assumed power of .80, alpha of .05, quit intention variance of 1.80,35 and a quit intention effect size of .11, a pooled estimate based on studies of anti-smoking messages and e-cigarette cues.14,25,36 We limited participation to users with a 90% or higher approval rate of past MTurk tasks and accounts registered in the US. Users also completed a brief screener to ensure they met the eligibility criteria: being able to read and understand English and being an established current smoker (ie, smoking 100+ cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoking every day or some days). Eligible users were directed to a Qualtrics survey.

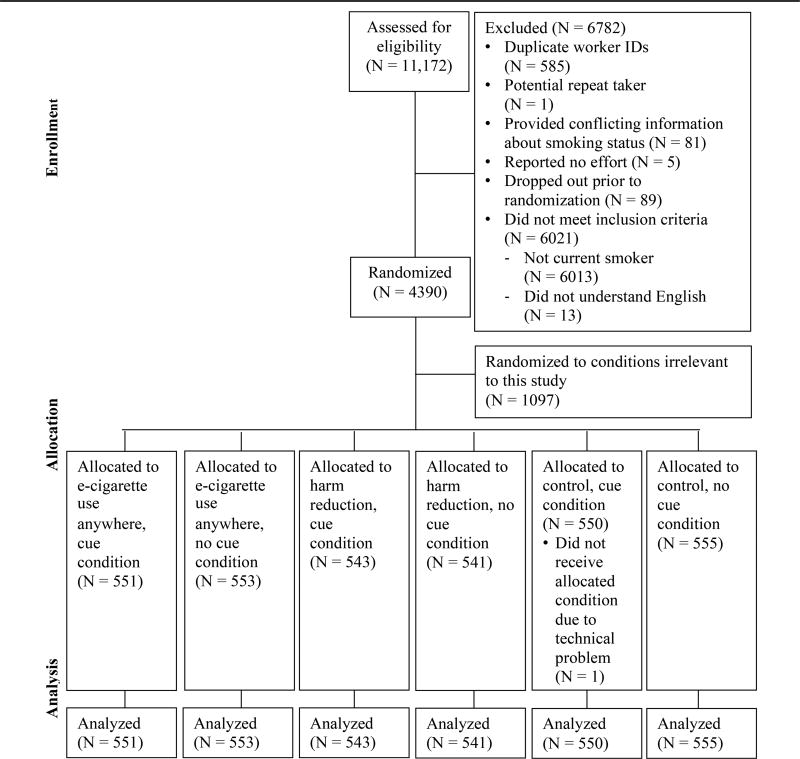

Participants were asked demographic, cigarette smoking background (ie, nicotine dependence, smoking recency), and e-cigarette advertising exposure questions and told they would be shown e-cigarette ads. Qualtrics randomly assigned them in equal numbers to one of 8 conditions, 6 of which are the focus of this study. The remaining 2 conditions tested variations in message form, a topic of ongoing research. In each condition, participants viewed 4 ads representing variations of the study condition. Study conditions combined one of 3 messages (e-cigarette use anywhere, harm reduction, control) with or without the e-cigarette cue. Each ad appeared on the computer screen for 10 seconds. The order of the ads was randomly determined for each participant. After exposure to all 4 ads, participants answered questions about their smoking cessation intention, smoking urges, and immediate smoking behavior, as well as questions about their past year quitting history and e-cigarette use. Upon completing the study, participants received a $2.00 USD incentive. Participants took, on average, 16.3 minutes to complete the survey. Figure 1 (CONSORT Diagram for Study Sample) outlines the process for creating the analytic sample.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram for Study Sample

Stimuli Development

Two MarkTen ads and 2 Fin ads were selected for use in the study from among 136 e-cigarette print ads obtained through an advertising monitoring service. The full-page, color ads ran in US consumer publications from July 2010 through December 2014. Ads were selected if they supported the 3 message conditions and if removing the e-cigarette images would not compromise the integrity of the ad. We manipulated the ads, using Adobe Photoshop, for the 6 experimental conditions. The manipulated factors were message content and e-cigarette cue presence. The 3 message conditions were “Use Evermist E-Cigs anywhere you want,” “Use Evermist E-Cigs as a less harmful alternative to cigarettes,” and “Use Evermist E-Cigs.” Both e-cigarette use anywhere and harm reduction messages have been used in actual e-cigarette print ads. Minor edits were made to make the sentence structure and punctuation parallel across study conditions and to substitute the brand name in the original messages with a fictitious brand (“Evermist E-Cigs”) used in a prior study.37 All 4 ads depicted a cigalike in various contexts (eg, next to a martini, used by a person). These cigalike images served as the cues in the e-cigarette cue conditions. In the no cue conditions, these images were removed.

Each ad was composed of the message to be tested, the fictitious brand name and logo, and ad image. The messages were located in the same spot and written in the same font as the taglines on the original ads, but the message text size was increased by 50% to enhance its readability and salience. Text that was irrelevant to the study (eg, health warning information) was removed from the ads. Apart from the manipulated features, the look of the ads remained consistent across study conditions. Stimuli are available upon request.

Measures

Outcomes

The primary outcome was quit intention, which was assessed with a 3-item scale: How [interested are you in quitting smoking, much do you plan to quit smoking, likely are you to quit smoking] regular cigarettes in the next 6 months? Each item was scored on a 5-point scale (eg, 1 = “not at all interested” to 5 = “extremely interested”). Item scores were averaged to create a composite score (α = 0.90).35

Secondary outcomes included smoking urge and smoking behavior. Smoking urge was assessed with the 10-item Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges.38 Each item was measured on a 5-point scale, and higher scores indicated greater urges (α = 0.93). To avoid triggering urge with a pre-manipulation self-report assessment,39 we only assessed smoking urge post-manipulation exposure. Smoking behavior was assessed with one dichotomous item: “Have you smoked a regular cigarette at any point while filling out this survey, even just one puff?”14

Tobacco use, e-cigarette advertising exposure, and demographics

Tobacco use, e-cigarette advertising exposure, and demographic questions were used to characterize the sample and to assess comparability of conditions. While screening participants for eligibility, we assessed their smoking status with 2 ordinal variables: number of cigarettes smoked over a lifetime and how often the participants smoked.40 To measure nicotine dependence, we used the heaviness of smoking index, which is the sum of 2 ordinal measures: number of cigarettes smoked per day (range: “0” for 0 – 10 cigarettes to “3” for 31+ cigarettes) and time to first cigarette of the day (range: “0” for 61+ minutes to “3” for 5 minutes or less).41,42 The smoking recency measure, which we analyzed as continuous, was: “When did you last smoke a cigarette?” (0 = “within the past hour” to 4 = “more than a month ago”).14 Past year quit history was assessed with “In the past 12 months, have you tried to quit smoking regular cigarettes?” (0 = “no,” 1 = “yes”).43

We measured e-cigarette ever use with a dichotomous item: “Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even just one time in your entire life?”44 Participants who indicated using an e-cigarette were asked how often they currently used e-cigarettes (0 = “not at all” to 3 = “every day”).45 To assess prior exposure to e-cigarette advertising, we asked: “In the past 30 days, have you seen or heard any advertisements for e-cigarettes?” (0 = “no,” 1 = “yes”).

Demographic items included age, sex, education, race, ethnicity, household income, number of members in the household, and US state. Household income, number of household members, and US state of residence were compared against the 2015 US federal poverty guidelines to create a dichotomous variable indicating whether participants were above or below the federal poverty guideline.46 Race and ethnicity were combined to create a 4-category variable: non-Hispanic, white; non-Hispanic, black; non-Hispanic, other/multi-race; and Hispanic.

Data Analysis

We used Stata/IC 12.1 and SPSS 24 to conduct intent-to-treat analyses with all randomized participants and listwise deletion to handle missing data (<1% of randomized cases). We calculated descriptive statistics by condition. We performed a 2-way ANOVA to investigate the main and interaction effects of e-cigarette message and cue on quit intention and smoking urge. Chi-square and logistic regression analyses were performed with smoking behavior. Because message and cue effects may vary by how recently the participant smoked a combustible cigarette, we analyzed message × smoking recency and cue × smoking recency interactions post hoc. Although our study was not specifically powered for these analyses, we felt the results could enrich interpretation of primary outcome results and inform future studies. The cue was included as a covariate in message × smoking recency analyses, and message was included as a covariate in cue × smoking recency analyses. All ANOVA models met the necessary statistical assumptions.47

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics. Study groups did not have any meaningful baseline differences. In each condition, about 40% of participants were 29 years of age or younger, over 50% had a college or advanced degree, and over 75% were non-Hispanic white. E-cigarette ad awareness was high, with over 70% of participants in each condition reporting seeing or hearing e-cigarette ads in the past month. Most participants reported smoking over 200 cigarettes during their lifetime (>87% in each condition) and currently smoking every day (>66% in each condition). Over two-thirds of participants in each condition reported ever use of e-cigarettes, but current e-cigarette use was low, with less than a quarter reporting e-cigarette use some days or every day.

Table 1.

Tobacco Use, E-cigarette Advertising Exposure, and Demographic Characteristics among Smokers by Experimental Condition (N = 3293)

| E-cig Anywhere | Harm Reduction | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Cue N = 551 |

No cue N = 553 |

Cue N = 543 |

No cue N = 541 |

Cue N = 550 |

No cue N = 555 |

|

| Sex (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Men | 45.4 | 45.4 | 47.5 | 47.9 | 46.0 | 44.3 |

| Women | 54.6 | 54.6 | 52.3 | 51.9 | 54.0 | 55.3 |

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Age (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 18 to 24 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 14.7 | 15.2 | 12.7 | 16.2 |

| 25 to 29 | 27.0 | 25.1 | 27.1 | 23.8 | 30.6 | 23.2 |

| 30 to 44 | 44.1 | 45.6 | 45.1 | 42.9 | 42.7 | 48.5 |

| 45 to 59 | 10.3 | 11.6 | 10.3 | 15.5 | 12.0 | 11.2 |

| 60+ | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Education (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Less than HS | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| HS or equivalent | 8.0 | 12.1 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 13.1 | 11.3 |

| Some college | 34.0 | 30.8 | 34.0 | 29.9 | 30.7 | 28.1 |

| College degree+ | 56.9 | 56.3 | 50.9 | 53.8 | 54.8 | 59.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Race (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 79.0 | 75.1 | 78.3 | 78.4 | 79.2 | 75.4 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6.3 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 8.0 | 5.8 | 7.0 |

| Non-Hispanic other/multi | 5.9 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 8.9 |

| Hispanic | 8.8 | 8.7 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 8.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Below FPG (%) | 13.7 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 12.2 |

| Seen/heard e-cig ads past month (%) | 73.0 | 73.2 | 74.2 | 72.8 | 71.3 | 74.1 |

| Last smoked a cigarette (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| >1 month ago | 2.0 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| >1 week to 1 month ago | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| >24 hours to 1 week ago | 10.3 | 10.3 | 6.6 | 12.0 | 8.9 | 11.2 |

| >1 hour to 24 hours ago | 31.6 | 32.2 | 32.2 | 28.3 | 30.4 | 29.7 |

| Within the past hour | 51.9 | 50.5 | 53.6 | 54.2 | 55.6 | 53.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Cessation attempt past year (%) | 56.2 | 55.0 | 52.0 | 50.8 | 53.5 | 55.5 |

| Lifetime cigarettes smoked (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 100 to 150 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 3.7 | 5.9 | 4.0 | 7.2 |

| 151 to 200 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 4.0 |

| 201+ | 91.5 | 87.9 | 92.6 | 91.1 | 91.3 | 88.8 |

|

| ||||||

| How often smoke cigarettes (%) | ||||||

| Some days | 33.2 | 32.0 | 28.0 | 29.6 | 29.8 | 28.8 |

| Every day | 66.8 | 68.0 | 72.0 | 70.4 | 70.2 | 71.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Nicotine dependence (M, SD)a | 2.2(1.5) | 2.2(1.5) | 2.2(1.5) | 2.2(1.5) | 2.2(1.4) | 2.3(1.6) |

| Ever used e-cig (%) | 73.8 | 69.8 | 71.0 | 67.9 | 71.9 | 72.1 |

| How often use e-cigs (%)b | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Not at all | 17.5 | 14.4 | 19.4 | 19.2 | 13.8 | 15.2 |

| Rarely | 61.8 | 61.3 | 59.4 | 58.5 | 61.6 | 61.9 |

| Some days | 15.0 | 17.5 | 15.2 | 14.8 | 17.1 | 16.2 |

| Every day | 5.7 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 6.8 |

Note.

Participation was limited to MTurk users with a 90% or higher approval rate of past MTurk tasks and accounts registered in the US. Eligible participants also reported being able to read and understand English, smoking 100+ cigarettes in their lifetime, and currently smoking every day or some days.

HS = high school, FPG = federal poverty guidelines, e-cig = e-cigarette

Range: low (0) – high (6)

Among e-cigarette ever users (N = 2321)

Table 2 presents the ANOVA and chi-square results for all outcomes. For our primary outcome of quit intention and secondary outcome of smoking urge, there were no statistically significant message or cue effects and no significant message × cue interactions. In other words, quit intention and smoking urge across the e-cigarette ad message conditions were not significantly different. Furthermore, quit intention and smoking urge were not significantly different when an e-cigarette cue was present versus absent. The effects of the message did not differ depending on whether or not an e-cigarette cue was present.

Table 2.

ANOVA and Chi-square Results for Quit Intention, Smoking Urge, and Smoking Behavior

| Quit Intention | Smoking Urge | Smoked During Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| F | p | F | p | Chi-square | p | |

| Main Effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Message | 1.90 | 0.150 | 1.65 | 0.192 | 7.79 | .020 |

| Cue | 0.40 | 0.525 | 0.05 | 0.826 | 0.16 | .693 |

|

| ||||||

| Interaction Effects | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Message × Cue | 1.84 | 0.158 | 0.62 | 0.536 | NA | NA |

| Message × Smoking recency | 0.97 | 0.380 | 1.54 | 0.215 | NA | NA |

| Cue × Smoking recency | 0.27 | 0.605 | 0.35 | 0.555 | NA | NA |

Note.

NA = not applicable

For smoking behavior, however, there was a statistically significant main effect of the message, with 13.8% of participants in the control condition, 10.7% of participants in the e-cigarette use anywhere condition, and 10.3% of participants in the harm reduction condition reporting smoking during the study (p = .020). Participants receiving the e-cigarette use anywhere message and harm reduction message reported lower odds of smoking during the study than those receiving the control message (AOREUA = 0.75, 95%CI = 0.58, 0.97, p = .026; AORHR*** = 0.72, 95%CI = 0.55, 0.93, p = .013). No significant cue or message × cue interaction effects were found (all ps ≥ .05).

Post hoc analyses investigated smoking recency as a moderator of message and cue effects. The relationship between message type and the outcomes of quit intention, smoking urge, and smoking during the study did not depend on how recently the participant smoked a combustible cigarette. Likewise, the effect of the cue on these outcomes was not contingent on smoking recency. Specifically, message × smoking recency effects on quit intention and smoking urges were not statistically significant. Similarly, no cue × smoking recency effects on quit intention or smoking urges emerged. For smoking during the study, message × smoking recency and cue × smoking recency interactions were non-significant (all ps ≥ .05).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to manipulate 2 features of e-cigarette print advertisements – message content and e-cigarette cues – and to test the main and interaction effects of these manipulations on outcomes related to combustible cigarette smoking cessation. Contrary to our expectations, neither the message nor cue alone affected quit intention. Moreover, we did not detect a message × cue interaction for quit intention.

The lack of e-cigarette cue effects conflicts with results from previous experiments with smokers that found that e-cigarette images increased smoking urges28 and sparked immediate smoking.14 Because our measures of these outcomes were either identical or comparable to those in these previous studies, this leads us to speculate that the differences in results may be due to differences in stimuli. In contrast to the print ads and 40-second total duration of exposure in our study, previous studies used video ads with stimuli exposure durations ranging from one minute to 4 or more minutes.14,28 The longer duration of exposure and more vivid nature of the video ads may have resulted in a greater dose of the e-cigarette cue and, in turn, greater effects.

Notably, the effects of vividness of cue presentation on persuasion have been subject to debate. In the combustible cigarette literature, less vivid stimuli (eg, pictures of smoking) have increased smoking urges while more vivid stimuli (eg, movie featuring smoking) have had either no effect on smoking urges21 or a pro-smoking effect under certain conditions, like when participants experienced low engagement in the narrative.48 A review of the persuasive effects of vivid media (eg, television versus print) confirmed that the effect of vividness may depend on boundary conditions (eg, message complexity, cue salience).49 Future studies should formally compare the effects of various e-cigarette cue presentations and investigate potential moderating factors.

It is also worth noting that although longer exposure times to e-cigarette print ads might result in greater cue effects, they could reduce the generalizability of results. The brief exposure to stimuli in this experiment might be more typical of incidental print ad exposure experienced in the real world than longer exposure times. Over time, smokers may be repeatedly exposed to e-cigarette advertisements in magazines and other channels like retail displays and social media. To enhance the generalizability of results further, future studies could consider repeatedly exposing participants to ad stimuli over time.

Although the e-cigarette messages did not have differential effects on quit intention or smoking urge, they did have differential effects on smoking behavior. The odds of smoking during the study were lower for the harm reduction and e-cigarette use anywhere messages than for the control message. One explanation may be that both messages discourage smoking by highlighting potential advantages of e-cigarettes relative to combustible cigarettes. Any pro-smoking effect of the e-cigarette use anywhere message could have been outweighed by its pro-e-cigarette use effect. Thus, rather than cueing cigarette smoking, these ads may have cued thoughts about switching to e-cigarettes as a way to smoke fewer conventional cigarettes. Another explanation is that the e-cigarette messages led smokers to believe that e-cigarettes are effective cessation aids. E-cigarette companies are known to use a variety of euphemistic phrases to suggest that their products can be used for cessation.50 Despite not making overt cessation claims, these messages may serve as cessation claims.

Notably, the absolute differences in smoking behavior between the control condition and the harm reduction and e-cigarette use anywhere conditions were relatively low (3%–4%). Future research should determine if our findings can be replicated and should investigate potential pathways of the observed effect. Moreover, because this study investigated only a single version of each message, future studies should utilize different versions of the messages.51

In our study, smoking recency did not influence message or cue effects on study outcomes. This finding is consistent with previous research on smoking cues and nicotine deprivation, a rough proxy for smoking recency.52 Smokers who are more nicotine-deprived report greater smoking urge than smokers who are less nicotine-deprived but not necessarily greater urge in response to e-cigarette cues.52 Because smoking recency was self-reported and we had limited statistical power, our results should be interpreted with caution. Further research on the potential moderating roles of smoking recency or nicotine deprivation could yield insights into when smokers may be more susceptible or less susceptible to message and cue effects.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, between our development of the stimuli in July 2015 and launch of the survey in November 2015, several US states and localities prohibited e-cigarette use in various venues.53,54 There were no geographic differences across the message conditions, suggesting people living in jurisdictions where e-cigarette use was restricted were equally distributed. However, this phenomenon may have dampened the overall effect of the e-cigarette use anywhere message. If participants knew that e-cigarettes could not, in practice, be used anywhere, they might have dismissed the e-cigarette use anywhere message, undermining its persuasive potential. Second, before exposure to the stimuli, participants were informed they would be shown e-cigarette advertisements. We wanted to avoid confounding the effect of the manipulations with confusion or misinterpretation of the ad. Nevertheless, this instruction might have suppressed activation of cigarette-related cognitions and diluted pro-smoking effects. Third, our measure of smoking behavior captured participants who smoked at any time during the study. Thus, it is possible for participants to have smoked before seeing the ads, and using a measure specific to post-experimental exposure would have enabled us to isolate the effect of the ads better. Despite the imprecision of our measure, randomization should allow us to compare the effects of the ad manipulations on smoking behavior across conditions. The ads also were shown early in the survey (estimated 2 minutes from the start), so there was only a brief window before ad exposure during which participants could have smoked. Fourth, the use of a fictitious brand may reduce the external validity of our findings. We used a fictitious brand to isolate the effect of the manipulations and to minimize the potential for interactions with the actual brands. In the real world, e-cigarette messages and cues are likely to interact with e-cigarette branding, but investigating these interactions were beyond the scope of this study. Lastly, our sample, though large and diverse, was a convenience sample, and thus, not representative of US smokers, which reduces the external validity of our findings. Future studies should investigate whether our findings can be replicated in a nationally representative sample of smokers.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

If our findings can be replicated, the regulatory implications will need to be considered carefully. On the one hand, these e-cigarette marketing messages may discourage combustible cigarette use and promote switching to a purportedly less harmful product: e-cigarettes. On the other hand, these messages may represent unauthorized modified risk or cessation claims; this is particularly true of the harm reduction message. The deeming regulation, which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finalized in 2016, stated that e-cigarette companies cannot claim that their product is less harmful than other tobacco products without providing substantiation to the agency and receiving FDA’s authorization that their product is indeed a modified risk tobacco product.55 Additionally, companies cannot make cessation claims about e-cigarettes unless they submit a medicinal product application to FDA’s Center for Drug and Evaluation Research.55 No currently marketed e-cigarettes have received FDA authorization to make harm reduction or cessation claims.55 By stating that e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes and implicitly suggesting e-cigarettes could be used for cessation,50 harm reduction messages, like the one tested in this study, may not be allowed by FDA or other regulatory agencies.

Our study contributes to the literature on the effects of e-cigarette ads on smoking and its antecedents. Whereas additional studies are needed to replicate these findings, our results suggest that e-cigarette messages and cues may either have no effect on smoking or, in the case of e-cigarette use anywhere and harm reduction messages, may actually discourage smoking. FDA should carefully consider these and other data as they consider e-cigarette advertising regulations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (grant number P50CA180907). Additional project funds were provided by Kurt Ribisl and the UNC Lineberger Cancer Prevention and Control Leadership Fund. Additional support for CLJ’s effort was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (award number F31DA039609). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. The authors also thank Brian Southwell for his input on this study, Dannielle Kelley for facilitating access to the ads used as stimuli, and Tara Queen for her input on statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr Jo was a part-time employee at the FDA Center for Tobacco Products from July 2012 to July 2015. Dr Ribisl has served as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers and Internet tobacco vendors. The authors have no other competing interests to report.

Contributor Information

Catherine L. Jo, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Shelley D. Golden, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Seth M. Noar, School of Media and Journalism, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Christine Rini, John Theurer Cancer Center, Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ.

Kurt M. Ribisl, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- 1.Kornfield R, Huang J, Vera L, Emery SL. Rapidly increasing promotional expenditures for e-cigarettes. Tob Control. 2015;24(2):110–111. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) E-cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: USDHHS, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. pp. 1–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truth Initiative. Vaporized: youth and young adult exposure to e-cigarette marketing. Washington, DC: truthinitiative.org; 2015. [Accessed October 17, 2016]. Available at: http://truthinitiative.org/sites/default/files/Vaporized-Youth_and_young_adult_exposure_to_e-cigarette_marketing.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsalinos KE, Polosa R. Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5(2):67–86. doi: 10.1177/2042098614524430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, et al. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):e33–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindblom EN. Effectively regulating e-cigarettes and their advertising--and the First Amendment. Food Drug Law J. 2015;70(1):57–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, et al. E-cigarettes: an evidence update. London, UK: Public Health England; 2015. [Accessed April 19, 2017]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/457102/Ecigarettes_an_evidence_update_A_report_commissioned_by_Public_Health_England_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: USDHHS, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. pp. 1–943. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim AE, Lee YO, Shafer P, et al. Adult smokers’ receptivity to a television advert for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Control. 2015;24(2):132–135. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villanti AC, Rath JM, Williams VF, et al. Impact of exposure to electronic cigarette advertising on susceptibility and trial of electronic cigarettes and cigarettes in US young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):1331–1339. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durkin SJ, Bayly M, Wakefield M. Can e-cigarette ads undermine former smokers? An experimental study. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(3):263–277. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maloney EK, Cappella JN. Does vaping in e-cigarette advertisements affect tobacco smoking urge, intentions, and perceptions in daily, intermittent, and former smokers? Health Commun. 2016;31(1):129–138. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.993496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grana R, Ling PM. “Smoking Revolution” a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii3–iii9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Andrade M, Hastings G, Angus K. Promotion of electronic cigarettes: tobacco marketing reinvented? BMJ. 2013;347:f7473. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy-Hoefer R, Hyland A, Higbee C. Perceived effectiveness of tobacco countermarketing advertisements among young adults. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):725–734. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):127–138. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter BL, Robinson JD, Lam CY, et al. A psychometric evaluation of cigarette stimuli used in a cue reactivity study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):361–369. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lochbuehler K, Engels RC, Scholte RH. Influence of smoking cues in movies on craving among smokers. Addiction. 2009;104(12):2102–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94(3):327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Droungas A, Ehrman RN, Childress AR, O’Brien CP. Effect of smoking cues and cigarette availability on craving and smoking behavior. Addict Behav. 1995;20(5):657–673. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang Y, Cappella JN, Strasser AA, Lerman C. The effect of smoking cues in antismoking advertisements on smoking urge and psychophysiological reactions. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(3):254–261. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S, Cappella JN, Lerman C, Strasser AA. Effects of smoking cues and argument strength of antismoking advertisements on former smokers’ self-efficacy, attitude, and intention to refrain from smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):527–533. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutgers School of Public Health. [Accessed April 17, 2017];Trinkets & Trash. Available at: https://trinketsandtrash.org/search_results.php?ResultLimit=hundred.

- 27.Stanford School of Medicine. [Accessed April 17, 2017];Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Available at: http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_ecigs.php?token2=fm_ecigs_st474.php&token1=fm_ecigs_img27882.php&theme_file=fm_ecigs_mt067.php&theme_name=Tobacco%20Owned%20Brands&subtheme_name=Mark%20Ten,%20Altria.

- 28.King AC, Smith LJ, Fridberg DJ, et al. Exposure to electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) visual imagery increases smoking urge and desire. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(1):106–112. doi: 10.1037/adb0000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field M, Munafo MR, Franken IH. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between attentional bias and subjective craving in substance abuse. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):589–607. doi: 10.1037/a0015843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Cappella JN, Lerman C, Strasser AA. Smoking cues, argument strength, and perceived effectiveness of antismoking PSAs. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(4):282–290. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berinsky A, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis. 2012;20(3):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crump MJ, McDonnell JV, Gureckis TM. Evaluating Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a tool for experimental behavioral research. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halkjelsvik T. Do disgusting and fearful anti-smoking advertisements increase or decrease support for tobacco control policies? Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(4):744–747. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall MG, Ribisl KM, Brewer NT. Smokers’ and nonsmokers’ beliefs about harmful tobacco constituents: implications for FDA communication efforts. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(3):343–350. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein WM, Zajac LE, Monin MM. Worry as a moderator of the association between risk perceptions and quitting intentions in young adult and adult smokers. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(3):256–261. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strasser AA, Cappella JN, Jepson C, et al. Experimental evaluation of antitobacco PSAs: effects of message content and format on physiological and behavioral outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(3):293–302. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, et al. Effects of advertisements on smokers’ interest in trying e-cigarettes: the roles of product comparison and visual cues. Tob Control. 2014;23(Suppl 3):iii31–iii36. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, et al. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed April 10, 2017];2013 NHIS questionnaire - sample adult. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Survey_Questionnaires/NHIS/2013/English/qadult.pdf.

- 41.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84(7):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii83–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study (NIDA) [Accessed May 14, 2017];PATH study data collection instruments: adult extended interview. Available at: https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/DownloadDocument?objectID=47878801.

- 44.Pepper JK, Emery SL, Ribisl KM, et al. How risky is it to use e-cigarettes? Smokers’ beliefs about their health risks from using novel and traditional tobacco products. J Behav Med. 2015;38(2):318–326. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amato MS, Boyle RG, Levy D. How to define e-cigarette prevalence? Finding clues in the use frequency distribution. Tob Control. 2016;25(e1):e24–29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed April 10, 2017];2015 Poverty Guidelines. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/2015-poverty-guidelines.

- 47.Keppel G, Wickens TD. Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lochbuehler K, Peters M, Scholte RH, Engels RC. Effects of smoking cues in movies on immediate smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(9):913–918. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor SE, Thompson SC. Stalking the elusive “vividness” effect. Psychol Rev. 1982;89(2):155–181. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramamurthi D, Gall PA, Ayoub N, Jackler RK. Leading-brand advertisement of quitting smoking benefits for e-cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2057–2063. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Keefe DJ. Message generalizations that support evidence- based persuasive message design: specifying the evidentiary requirements. Health Commun. 2015;30(2):106–113. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.974123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiffany ST, Warthen MW, Goedeker KC. The functional significance of craving in nicotine dependence. In: Bevins RA, Caggiula AR, editors. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, The Motivational Impact of Nicotine and its Role in Tobacco Use. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska Press; 2009. pp. 171–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marynak K, Holmes CB, King BA, et al. State laws prohibiting sales to minors and indoor use of electronic nicotine delivery systems – United States, November 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(49):1145–1150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. [Accessed June 2, 2016];States and municipalities with laws regulating use of electronic cigarettes. Available at: http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/ecigslaws.pdf.

- 55.US Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. [Accessed June 2, 2016];21 CFR Parts 1100, 1140, and 1143. 2016 Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/05/10/2016-10685/deeming-tobacco-products-to-be-subject-to-the-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-as-amended-by-the. [PubMed]