Abstract

Background

Outcomes after stroke in those with diabetes are not well characterized, especially by sex and age. We sought to calculate the sex- and age-specific risk of cardiovascular outcomes after ischemic stroke among those with diabetes.

Methods

Using population-based demographic and administrative health care databases in Ontario, Canada, all patients with diabetes hospitalized with index ischemic stroke between April 1, 2002 and March 31, 2012 were followed for death, stroke, and myocardial infarction (MI). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Fine-Gray competing risk models estimated hazards of outcomes by sex and age, unadjusted and adjusted for demographics and vascular risk factors.

Results

Among 25495 diabetic patients with index ischemic stroke, incidence of death was higher in women than in men (14.08 per 100 person-years [95% CI 13.73–14.44] vs. 11.89 [11.60–12.19]), but was lower after adjustment for age and other risk factors (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.95 [0.92–0.99]). Recurrent stroke incidence was similar by sex, but men were more likely to be readmitted for MI (1.99 per 100 person-years [1.89–2.10] vs 1.58 [1.49–1.68] among females). In multivariable models, females had a lower risk of readmission for any event (HR 0.96 [95% CI 0.93–0.99]).

Conclusions

In this large, population-based, retrospective study among diabetic patients with index stroke, women had higher unadjusted death rate but lower unadjusted incidence of MI. In adjusted models, females had a lower death rate compared to males, although the increased risk of MI among males persisted. These findings confirm and quantify sex differences in outcomes after stroke in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: epidemiology, stroke, diabetes, gender differences, sex differences, mortality, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

There are sex differences in the risk of cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes. Compared to men, women with diabetes have a 40% higher risk of incident coronary heart disease1 and 27% higher risk of stroke.2 However, sex differences in outcomes in diabetic patients following an incident event are unclear, with conflicting findings in previous studies.3, 4 Sex differences have been demonstrated for myocardial infarction (MI) 5, 6 and other cardiovascular disease,7 but data on sex differences in outcomes among people with diabetes after incident stroke are less consistent. Relatively small studies have reported higher in-hospital mortality8 and long-term mortality9 for diabetic females, but others have shown no association of sex and outcomes10, 11 Furthermore, prior studies mostly examined mortality and did not measure readmission rates. Studies to date have not adequately assessed for socioeconomic status and medication usage, which may confound the relationship between sex and outcomes. There is a lack of reliable population-based data on the effect of sex on mortality and readmissions among diabetic patients following an incident stroke.

The objective of this analysis was to examine differences in cardiovascular events and mortality by sex and age among those with diabetes after ischemic stroke in Ontario. We hypothesized that women had higher mortality compared to men and that the readmission risk for cardiovascular events differed by sex.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a population-based sample using linked administrative databases in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. Because of government-funded health insurance for all permanent residents of Ontario, data were available on the entire population. The Ontario Registered Persons Database (RPDB) provided data on mortality after stroke, and the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (CIHI-DAD) identified readmissions for stroke and myocardial infarction (MI). CIHI-DAD contains ≤25 diagnosis fields for admissions to Ontario hospitals and uses the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision coding system (ICD-10) for the year 2002 onwards. In previous studies of CIHI-DAD in Canadian hospitals, there was high positive predictive value (85% for ischemic stroke, 98% for intracerebral hemorrhage, and 91% for subarachnoid hemorrhage) and Kappa of 0.89 for agreement between coder and researcher using ICD-10 codes.12 The Ontario Drug Benefits (ODB) database provided information on prescriptions filled by all residents aged ≥65 years. These databases were linked via a unique, encoded identifier and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). The institutional ethics review board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre approved this study.

Sample selection

We included those with an index ischemic stroke admission during the study period in CIHI-DAD, identified with any of the following ICD-10 codes: I63 (excluding I63.6), I64, H34.0, or H34.1 in the “most responsible diagnosis” field, which has been shown to have 92% accuracy for stroke diagnosis.13 We identified diagnosis of diabetes prior to or at the time of the index ischemic stroke admission by linking to the Ontario Diabetes Database (ODD), which has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 99%.14 We limited the sample to those with ischemic stroke and diabetes who were ≥18 years of age at the time of admission. Index stroke admissions from 4/1/2002 to 3/312012 were included, with maximum follow-up to 3/31/2013.

Baseline assessment

Age was calculated as age at admission for index ischemic stroke. Income was estimated using neighborhood-level household income and was categorized into quintiles. Duration of diabetes was calculated by using the diagnosis date in the ODD and was categorized into: 0 to <3, 3 to <6, and ≥6 years. Duration of Ontario residence was inferred from duration of having a health card and was categorized into: 0 to <5, 5 to <10 and ≥10 years. Using standard ICD-9 (prior to 2002) and ICD-10 (2002 onwards) code clusters, we identified history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), atrial fibrillation, hypertension, MI, coronary artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD).

The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated using all diagnosis codes and types from all hospitalizations during the two year period prior to and including the index admission, using ≤25 available ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for each hospitalization. Since all participants in this analysis had diabetes, the diabetes indicators were excluded from our CCI calculation. The CCI was dichotomized into <2 versus ≥2, as in previous research.15

Only patients ≥65 years of age had complete information on prescription medication use. Baseline medication was defined as any prescription medication use within a 120-day window after the index stroke discharge, and medication classes included diabetic, statin, and anti-hypertensive medications as well as warfarin. Aspirin, which is available over-the-counter, had incomplete capture; hence, antiplatelet medication use was not adjusted for in the sensitivity analyses.

Longitudinal follow-up

Outcomes were: death, any-cause readmission, stroke/TIA readmission, MI readmission, stroke or MI readmission, and a composite of death or any-cause readmission. To create these outcomes, hospital readmissions for the following were assessed: recurrent stroke/TIA (ICD-10 code I63 [excluding I63.6], I64, H34.0, H34.1, G45 [excluding G45.4], H34.0), intracerebral hemorrhage (I61), recurrent CAD including MI (acute MI, codes I21, I22; unstable angina, code I20) and cardiac procedures (coronary artery bypass graft and percutaneous cardiac intervention).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were reported in the overall sample and stratified by sex. We calculated proportions for categorical variables and means and medians for continuous variables. Incidence was calculated as the incidence of each outcome per 100 person-years (with 95% confidence intervals), reported by age and sex subgroups. Two significance tests were performed using a Poisson regression model: one for the group comparison within each stratum, and the other for the overall test of significance of that stratum.

For all readmission outcomes (excluding death), a competing risk model proposed by Fine and Gray16 was used to estimate the hazard ratio and 95% CI of outcomes, with death defined as the competing risk. For the outcome of death, Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio and 95% CI. Models included demographic variables (age, sex, and income) and vascular risk factors (hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke or TIA, MI, CAD, PVD, and CCI). A sensitivity analysis was performed among those aged ≥65 years, among whom medication use was adjusted for and categorized into anti-hypertensive medication use, diabetes medication use, statin use, and warfarin use. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Out of 84,731 index ischemic stroke admissions during the study time period, 29,752 had diabetes prior to index admission and were included. After applying exclusions (age <18 years; death during index admission; death after index discharge but before any readmissions), the final sample consisted of 25,495 individuals. Median follow-up time was 3.2 years.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics in the entire sample (n=25,495) and by sex (11,902 females and 13,593 males). Compared to males, females were older and more frequently from lower neighborhood income quintiles. Females more often had history of prior stroke or TIA, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension but less often had history of MI, CAD or PVD; females had lower CCI scores but longer average length of hospital stay. In those aged ≥65 years, females at baseline were significantly less often taking diabetic or statin medications.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of sample and numbers of outcomes*

| Variable | Entire Sample | Female | Male | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Number of participants | 25495 | 11902 (46.7) | 13593 (53.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Baseline characteristics: | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 73.4 (11.6) | 75.6 (11.5) | 71.5 (11.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Neighborhood income: | <0.001 | |||

| 1st quintile (lowest) | 6438 (25.3) | 3152 (26.5) | 3286 (24.2) | |

| 2nd quintile | 5841 (22.9) | 2791 (23.4) | 3050 (22.4) | |

| 3rd quintile | 4896 (19.2) | 2277 (19.1) | 2619 (19.3) | |

| 4th quintile | 4449 (17.5) | 1940 (16.3) | 2509 (18.5) | |

| 5th quintile (highest) | 3871 (15.2) | 1742 (14.6) | 2129 (15.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes duration: | 0.337 | |||

| 0 to <3 years | 5983 (23.5) | 2780 (23.4) | 3203 (23.6) | |

| 3 to <6 years | 3683 (14.4) | 1683 (14.1) | 2000 (14.7) | |

| ≥6 years | 15829 (62.1) | 7439 (62.5) | 8390 (61.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Duration of residence in Ontario: | 0.477 | |||

| 0 to <5 years | 462 (1.8) | 203 (1.7) | 259 (1.9) | |

| 5 to <10 years | 629 (2.5) | 291 (2.4) | 338 (2.5) | |

| ≥10 years | 24404 (95.7) | 11408 (95.8) | 12996 (95.6) | |

|

| ||||

| History of stroke or TIA | 2031 (8.0) | 984 (8.3) | 1044 (7.7) | 0.072 |

|

| ||||

| History of atrial fibrillation | 4614 (18.1) | 2501 (21.0) | 2113 (15.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| History of hypertension | 16161 (63.4) | 7848 (65.9) | 8313 (61.2) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| History of MI | 2575 (10.1) | 1105 (9.3) | 1470 (10.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| History of CAD | 5619 (22.0) | 2424 (20.4) | 3195 (23.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| History of PVD | 1257 (4.9) | 476 (4.0) | 781 (5.7) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Charlson index score: | 0.008 | |||

| 0–1 | 6801 (26.7) | 3268 (27.5) | 3533 (26.0) | |

| ≥2 | 18694 (73.3) | 8634 (72.5) | 10060 (74.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD) | 16.6 (26.7) | 17.8 (27.6) | 15.5 (25.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Overall frequency of outcomes: | ||||

|

| ||||

| Death | 12435 (48.8) | 6115 (51.4) | 6320 (46.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Death within: | ||||

| 7 days | 108 (0.4) | 63 (0.5) | 45 (0.3) | 0.015 |

| 30 days | 805 (3.2) | 467 (3.9) | 338 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 year | 4517 (17.7) | 2324 (19.5) | 2193 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| 5 years | 10916 (42.8) | 5439 (45.7) | 5477 (40.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for any cause | 17406 (68.3) | 8051 (67.6) | 9355 (68.8) | 0.044 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for any cause within: | ||||

| 30 days | 1706 (6.7) | 767 (6.4) | 939 (6.9) | 0.139 |

| 1 year | 9871 (38.7) | 4614 (38.8) | 5257 (38.7) | 0.88 |

| 5 years | 16402 (64.3) | 7621 (64) | 8781 (64.6) | 0.345 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for any cause or death | 20135 (79.0) | 9553 (80.3) | 10582 (77.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for any cause or death within: | 0.009 | |||

| 30 days | 2381 (9.3) | 1172 (9.8) | 1209 (8.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 year | 11799 (46.3) | 5681 (47.7) | 6118 (45) | |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for stroke or MI | 5876 (23.0) | 2647 (22.2) | 3229 (23.8) | 0.004 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for stroke or MI within: | ||||

| 30 days | 538 (2.1) | 245 (2.1) | 293 (2.2) | 0.591 |

| 1 year | 2591 (10.2) | 1196 (10) | 1395 (10.3) | 0.573 |

| 5 years | 5236 (20.5) | 2372 (19.9) | 2864 (21.1) | 0.025 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for stroke | 3794 (14.9) | 1791 (15) | 2003 (14.7) | 0.484 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for stroke within: | ||||

| 30 days | 472 (1.9) | 212 (1.8) | 260 (1.9) | 0.437 |

| 1 year | 1808 (7.1) | 867 (7.3) | 941 (6.9) | 0.262 |

| 5 years | 3429 (13.4) | 1620 (13.6) | 1809 (13.3) | 0.48 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for MI | 2512 (9.9) | 1036 (8.7) | 1476 (10.9) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Readmission for MI within: | ||||

| 30 days | 66 (0.3) | 33 (0.3) | 33 (0.2) | 0.589 |

| 1 year | 844 (3.3) | 360 (3) | 484 (3.6) | 0.017 |

| 5 years | 2149 (8.4) | 899 (7.6) | 1250 (9.2) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| CABG or PCI | 1076 (4.2) | 333 (2.8) | 743 (5.5) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Baseline medications for those aged ≥65 yr: | ||||

|

| ||||

| Number of participants aged ≥65 yr | 19619 (76.9) | 9788 (82.2) | 9831 (72.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Diabetic medications | 11656 (59.4) | 5655 (57.8) | 6001 (61) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Statin medications | 12724 (64.9) | 6096 (62.3) | 6628 (67.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Warfarin | 4248 (21.7) | 2189 (22.4) | 2059 (20.9) | 0.016 |

|

| ||||

| Anti-hypertensive medications | 15778 (80.4) | 7923 (80.9) | 7855 (79.9) | 0.065 |

values are number and column percentages in parentheses unless otherwise indicated;

TIA=transient ischemic attack; MI=myocardial infarction; CAD=coronary artery disease; PVD=peripheral vascular disease; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; NA=specific values not reported due to identifiability with small cell sizes; IQR=interquartile range

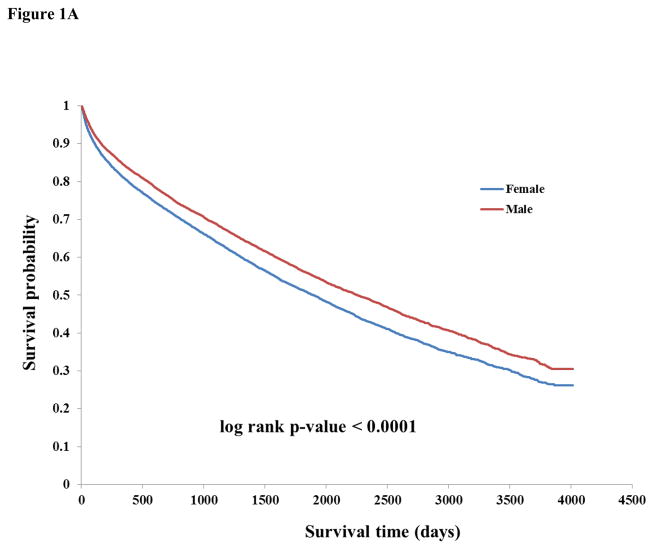

There were 12,435 deaths during follow-up. The overall frequencies of outcomes by time interval are listed in Table 1. The unadjusted incidence of death was higher among females (14.08 per 100 person-years, 95% CI 13.73–14.44 vs. 11.89, 95% CI 11.60–12.19 among males) and there were higher rates of death among higher age groups (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier curves showed lower survival probability for females compared to males (p<0.0001) (Figure 1A). After adjusting for age, income, vascular risk factors, and CCI, women had lower risk of death compared to men (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.92–0.99, Table 3). Among those ≥65 years old with or without adjustment for medications, a similar finding of lower risk of death among females was seen (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.97 and HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90–0.97, respectively).

Table 2.

Incidence rate of outcomes per 100 person-years, by subgroups of sex and age

| Outcome | Overall rate (95% CI) | Rate among females (95% CI) | Rate among males (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By sex: | |||||

| Death | 12.88 (12.65–13.11) | 14.08 (13.73–14.44) | 11.89 (11.60–12.19) | <0.0001 | |

| Readmission for any cause | 26.60 (26.00–27.22) | 26.20 (25.33–27.10) | 26.95 (26.12–27.81) | 0.2 | |

| Readmission for any cause or death | 39.30 (38.49–40.13) | 41.71 (40.47, 43.00) | 37.35 (36.29–38.44) | <0.0001 | |

| Readmission for stroke | 2.86 (2.77–2.95) | 2.90 (2.76–3.03) | 2.82 (2.70–2.95) | 0.4 | |

| Readmission for MI | 1.80 (1.73–1.87) | 1.58 (1.49–1.68) | 1.99 (1.89–2.10) | <0.0001 | |

| Readmission for stroke or MI | 4.77 (4.65–4.90) | 4.59 (4.42–4.77) | 4.94 (4.77–5.11) | 0.006 | |

| By age group: | Overall rate (95% CI) | Rate among 18–64 yr olds (95% CI) | Rate among 65–79 yr olds (95% CI) | Rate among 80+ yr olds (95% CI) | p-value |

| Death | 12.88 (12.65–13.11) | 4.56 (4.31–4.82) | 11.20 (10.89–11.51) | 24.67 (24.06–25.29) | <0.0001 |

| Readmission for any cause | 26.60 (26.00–27.22) | 21.02 (19.94–22.15) | 28.85 (27.88–29.85) | 27.81 (26.77–28.89) | <0.0001 |

| Readmission for any cause or death | 39.30 (38.49–40.13) | 23.39 (22.27–24.57) | 37.73 (36.57–38.93) | 59.57 (57.67–61.53) | <0.0001 |

| Readmission for stroke | 2.86 (2.77–2.95) | 3.12 (2.92–3.34) | 2.95 (2.82–3.09) | 2.58 (2.44–2.73) | <0.0001 |

| Readmission for MI | 1.80 (1.73–1.87) | 2.17 (2.00–2.34) | 2.02 (1.91–2.14) | 1.32 (1.22–1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Readmission for stroke or MI | 4.77 (4.65–4.90) | 5.34 (5.07–5.63) | 5.13 (4.94–5.32) | 4.03 (3.84–4.22) | <0.0001 |

MI=myocardial infarction; CI=confidence interval

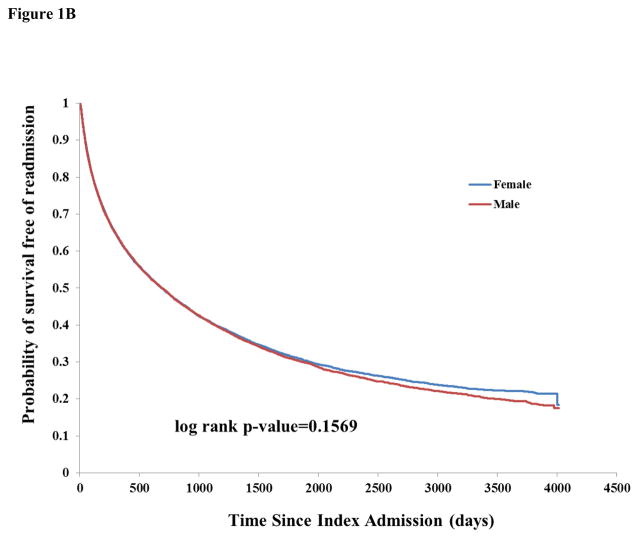

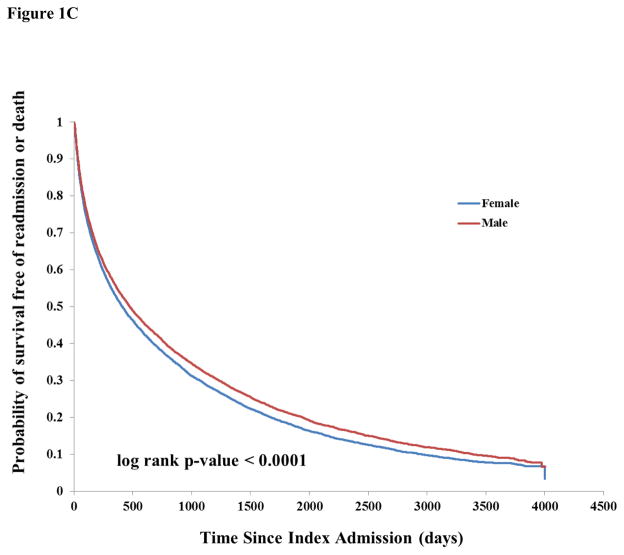

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by sex

Figure 1B: Kaplan-Meier curves of probability of survival free of readmission, stratified by sex

Figure 1C: Kaplan-Meier curves of probability of survival free of readmission or death, stratified by sex

Table 3.

Multivariable models of outcomes

| Competing risk models with death as competing risk | Cox regression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Any event | Stroke | MI | Stroke or MI | Death | |||||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Whole sample** | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | <0.0001 | 1.06 (1.06–1.06) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex† | 0.96 (0.93– 0.99) | 0.004 | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 0.2 | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | 0.001 | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.4 | 0.95 (0.92–0.99) | 0.01 |

| Among those ≥65 yr without adjustment for medications** | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.02 | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | <0.0001 | 0.98 (0.98–0.98) | <0.0001 | 1.07 (1.06–1.07) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex† | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.0006 | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.1 | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 0.1 | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.7 | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 0.0005 |

| Among those ≥65 yr with adjustment for medications@ | ||||||||||

| Age | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.6 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | <0.0001 | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | <0.0001 | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | <0.0001 | 1.06 (1.06–1.06) | 0.0001 |

| Female sex† | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | 0.0004 | 1.06 (0.98–1.14) | 0.1 | 0.92 (0.84–1.02) | 0.1 | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 0.8 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.0002 |

MI=myocardial infarction; HTN=hypertension; CAD=coronary artery disease; PVD=peripheral vascular disease;

male sex as referent;

models are adjusted for: income, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke or TIA, MI, CAD, PVD, and Charlson score;

models are adjusted for: income, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke or TIA, MI, CAD, PVD, Charlson score, anti-hypertensive medication use, diabetes medication use, statin use, and warfarin use

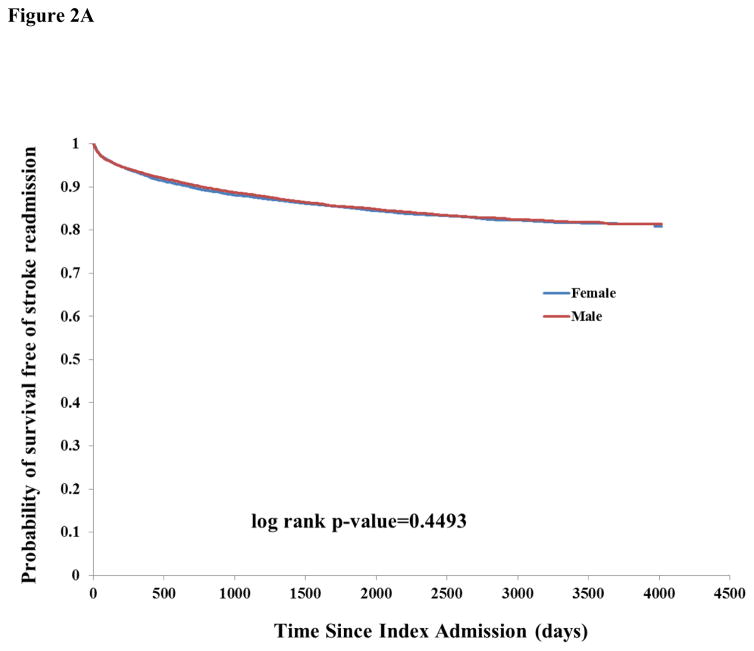

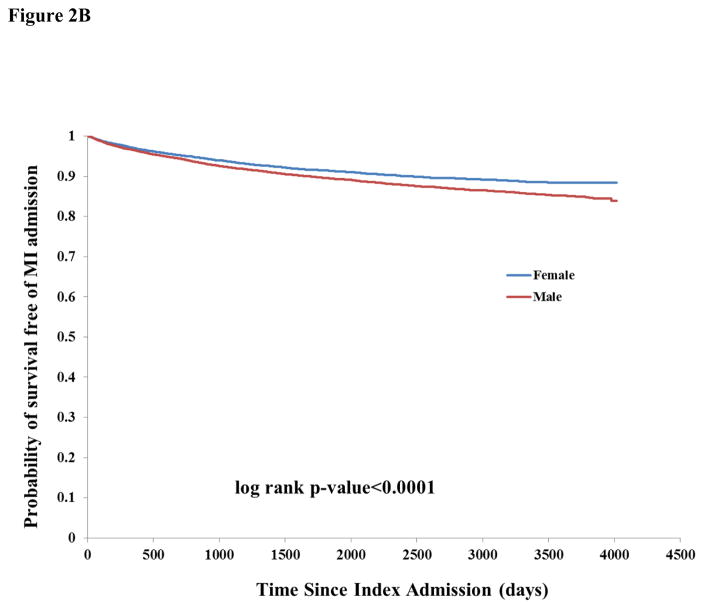

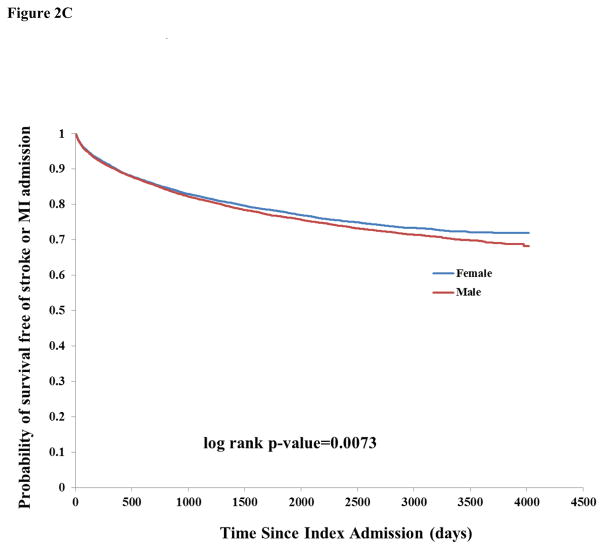

There were 17,406 any-cause readmissions during follow-up, of which 3,794 were for stroke and 2,512 for MI. The unadjusted incidence rate of readmission for any cause or for stroke was similar by sex (Table 2). There was higher unadjusted incidence among males for readmission due to MI (1.99, 95% CI 1.89–2.10 vs. 1.58, 95% CI 1.49–1.68 among females). There was a pattern of increased incidence of death and lower incidence of readmissions for stroke, MI, and stroke or MI among successively higher age categories, probably reflecting the competing risk of death for stroke and MI (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier curves showed a similar survival probability for males and females of any readmission (Figure 1B) and stroke readmission (Figure 2A), but a higher risk of MI readmission among males (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Figure 2A: Kaplan-Meier curves of probability of survival free of stroke readmission, stratified by sex

Figure 2B: Kaplan-Meier curves of probability of survival free of myocardial infarction readmission, stratified by sex

Figure 2C: Kaplan-Meier curves of probability of survival free of stroke or myocardial infarction readmission, stratified by sex

In multivariable competing risk models, females had a lower risk of readmission for any event (0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99, Table 3). There was no sex difference in risk of readmission for stroke, but females had a lower risk of MI readmission compared to males (0.88, 95% CI 0.81–0.95). Among those age ≥65 years with and without adjustment for medication usage, risk of readmission for any event remained lower in females but risk of MI readmission was no longer different by sex.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based, retrospective study using administrative linkage with full population coverage for the province of Ontario, we found that women with diabetes, compared to men, had higher unadjusted mortality and risk of readmission for any cause or death following an incident stroke but lower risk of readmission for MI. Unadjusted readmission rates for any cause and for stroke were similar by sex. Diabetic female patients with incident stroke were older and from a lower socioeconomic status. They were more likely to have hypertension and atrial fibrillation but less likely to have prior MI, CAD, or PVD. They were also less likely to be taking diabetic and statin medications at baseline and had a longer average length of hospital stay during the incident stroke, suggesting either differences in disease severity or disparities in optimal treatment by sex. These differences likely accounted for the unadjusted mortality difference seen by sex, because in adjusted models females had lower risk of death and lower risk of any-cause readmissions compared to males, although the increased risk of MI among males persisted after adjustment. Readmission rates for stroke remained similar between males and females in adjusted models. Also, as expected, there was a higher risk of mortality and lower risk of readmission with increasing age, likely due to the competing risk of death.

The impact of traditional cardiovascular risk factors varies by sex, especially for smoking (which carries a 25% greater risk for coronary heart disease among women than men17, 18) and diabetes.1, 2, 17, 18 In addition to traditional risk factors, there are risk factors specific to women, including gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, and placental disorders such as intrauterine growth restriction and stillbirth.17, 19–21 Polycystic ovarian syndrome, the most common female endocrine disorder, results in insulin resistance and development of metabolic syndrome.22 Oral contraceptive pills, used by 82% of sexually ever-active women, are associated with elevated risk of venous thrombosis, MI and ischemic stroke from a presumed pro-coagulant effect.18 Systemic autoimmune collagen vascular diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematous and rheumatoid arthritis, are more common in females and lead to accelerated atherosclerosis and progression to heart disease.20, 21 Depression is twice as common in women and associated with a 70% risk for heart disease; it can lead to non-adherence with diet, medications, and follow-up. 20

Social support and self-reported quality of life have also been reported to be lower in diabetic women.23, 24 Prior studies show that women have lower socioeconomic status and lower access to preventative measures and treatments for diabetes.7, 25 There are also treatment disparities – women are less likely to be prescribed medications for modifiable risk factors and, even when undergoing treatment, they are treated less effectively.20, 22, 26, 27 Our findings also reflect this female socioeconomic disadvantage as well as lower medication usage, despite universal health coverage.

Prior studies of sex differences in outcomes among diabetic stroke patients have been in smaller samples, focused on mortality, and with limited control of socioeconomic status and medication usage.8–10 In a Spanish prospective single center stroke registry of 561 diabetic stroke patients, there was higher mortality among women but similar stroke recurrence rates by sex.8 Elevated female mortality and similar stroke recurrence rates by sex were also reported in a single-center Chinese study of 2360 diabetic stroke patients.10 In a Swedish population-based study involving 2549 diabetic stroke patients under age 75 years, there was also higher mortality noted in females; however readmissions were not assessed.9

Our study included over 25,000 diabetic stroke patients and provides reliable evidence that women have higher mortality after stroke. We demonstrated that this difference is not present after adequate adjustment, and women actually have a lower age-adjusted risk for mortality. This finding is in agreement with a recent meta-analysis using 16,957 pooled individual participant data from 13 population-based stroke incidence studies from Europe, Australia, South America, and the Caribbean; it reported a lower crude survival rate in women at 1 and 5 years, which was reversed after adjustment.28 The 5-year pooled estimates had significant heterogeneity because few studies had follow-up beyond 1 year and there was missing data across studies, particularly on stroke risk factors such as diabetes (only 5 out of 13 studies reported diabetes status, n=667). Our current report consist of more patients than all 13 studies combined and provides confirmation that female sex, by itself, is not responsible for increased mortality after stroke in those with diabetes. Beyond mortality outcomes, we also demonstrate that there is no sex difference in stroke readmission risk, but males are at higher risk of readmission for MI. To our knowledge, there have been no prior studies among diabetic patients with incident stroke reporting the effect of sex and MI vs stroke readmissions.

We found that men had higher risk of MI readmission, suggesting a possible sex-specific sensitivity to different diabetes-related complications that has been previously demonstrated.27 Men, compared to women, have been reported to have higher coronary atheroma burden, more diffuse endothelial dysfunction, more severe structural abnormalities in the epicardial coronary arteries, and more vulnerable plaques.29 Young women are at lower risk of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke compared to males, presumably from the cardiovascular protective effects of estrogen.20, 29, 30 However, the risk profile reverses after menopause with a 10-fold rise in cardiovascular disease in women compared to a 4.5-fold rise in men of similar age.20, 29, 30 The protective effects of estrogen likely explains the disappearance of the elevated MI readmission risk when the sample is restricted to those above age 65, with or without adjustment for medication usage. Interestingly, this same protective effect was not seen for stroke readmission in analyses of the unadjusted, adjusted, and age >65 subgroup models. This suggests that diabetes in pre-menopausal women may blunt the protective effects of estrogen to varying degrees which may be organ specific.17, 20, 30, 31

This study attempts to overcome several limitations of prior studies in the area of sex differences after ischemic stroke. Due to universal health coverage in Ontario, the sample is unprecedented in that it includes all adults with diabetes and index ischemic stroke in a large Canadian province, not just patients from a single center or a population sample. Hence, this results in extensive population coverage over a long follow-up period with limited selection bias. Lack of power to detect sex differences is not a concern. Also, due to the unique linking among different databases, adjustment for the important confounders of socioeconomic status and medication use was possible.

There are limitations associated with the usage of administrative and claims-based data, which may be prone to misclassification and inaccuracy. For example, sample selection using ICD code I64, “stroke, not specified as hemorrhagic or infarct”, could possibly capture stroke-types other than ischemic stroke. However, the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis based on ICD-10-based codes has been shown to be excellent. We only have data on events that resulted in readmission; therefore some events such as TIA may be missed if patients were not admitted to the hospital. Data on stroke characteristics, such as subtype, severity, location, size, and discharge handicap were not available. Similarly, data was available on duration of diabetes but not on severity of diabetes as assessed by hemoglobin A1c levels. We were able to control for diabetic, statin and anti-hypertensive medication but could not assess for aspirin usage as it is available over the counter and therefore could not be reliably controlled. Aspirin’s role in preventing cardiovascular events in diabetic women is uncertain.22 There is insufficient evidence that aspirin has a sex-specific cardiovascular impact, and further study is indicated. Cardiovascular prevention may need to be tailored according to sex, and some studies have suggested differential effectiveness of interventions by sex.32, 33 A structured personalized approach may be more effective for women compared to men, but more research is needed.23

In summary, we demonstrated that diabetic female patients have higher mortality after incident stroke, but female sex was not an independent risk factor. Contrary to previous studies, female sex was associated with lower mortality after adjustment for vascular risk factors, demographics, socioeconomic status, and medication usage.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Mandip Dhamoon was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NS079422. Moira Kapral was supported by a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, Ontario Provincial Office. This study was funded by an operating grant from the Canadian Stroke Network. The Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences is supported by an operating grant from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Information. We thank IMS Brogan Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database. The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be attributed to any supporting or sponsoring agencies. No endorsement by the above is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors has a potential conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1542–1551. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as a risk factor for stroke in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts, including 775,385 individuals and 12,539 strokes. Lancet. 2014;383:1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi GM, Zhang YD, Geng C, et al. Profile and 1-Year Outcome of Ischemic Stroke in East China: Nanjing First Hospital Stroke Registry. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathisen SM, Dalen I, Larsen JP, Kurz M. Long-Term Mortality and Its Risk Factors in Stroke Survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meisinger C, Heier M, von Scheidt W, Kirchberger I, Hormann A, Kuch B. Gender-Specific short and long-term mortality in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients with incident acute myocardial infarction in the reperfusion era (the MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry) The American journal of cardiology. 2010;106:1680–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blondal M, Ainla T, Marandi T, Baburin A, Eha J. Sex-specific outcomes of diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention: a register linkage study. Cardiovascular diabetology. 2012;11:96. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flink L, Mochari-Greenberger H, Mosca L. Gender differences in clinical outcomes among diabetic patients hospitalized for cardiovascular disease. American heart journal. 2013;165:972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arboix A, Milian M, Oliveres M, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons J. Impact of female gender on prognosis in type 2 diabetic patients with ischemic stroke. European neurology. 2006;56:6–12. doi: 10.1159/000094249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eriksson M, Carlberg B, Eliasson M. The disparity in long-term survival after a first stroke in patients with and without diabetes persists: the Northern Sweden MONICA study. Cerebrovascular diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2012;34:153–160. doi: 10.1159/000339763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao W, An Z, Hong Y, et al. Sex differences in long-term outcomes among acute ischemic stroke patients with diabetes in China. Biology of sex differences. 2015;6:29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-015-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, Zhao X, Wang C, et al. Risk factors for poor outcome and mortality at 3 months after the ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamal N, Lindsay MP, Cote R, Fang J, Kapral MK, Hill MD. Ten-year trends in stroke admissions and outcomes in Canada. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2015;42:168–175. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2015.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokotailo RA, Hill MD. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using international classification of diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke. 2005;36:1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174293.17959.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:512–516. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein LB, Samsa GP, Matchar DB, Horner RD. Charlson Index comorbidity adjustment for ischemic stroke outcome studies. Stroke. 2004;35:1941–1945. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135225.80898.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samai AA, Martin-Schild S. Sex differences in predictors of ischemic stroke: current perspectives. Vascular health and risk management. 2015;11:427–436. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S65886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women--2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;123:1243–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen SE, Henry S, Bond R, Pearte C, Mieres JH. Sex-Specific Disparities in Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2015;17:49. doi: 10.1007/s11883-015-0523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in women. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2015;64:S33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regensteiner JG, Golden S, Huebschmann AG, et al. Sex Differences in the Cardiovascular Consequences of Diabetes Mellitus: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:2424–2447. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen AB, de Fine Olivarius N, Gannik D, Hindsberger C, Hollnagel H. Structured personal diabetes care in primary health care affects only women’s HbA1c. Diabetes care. 2006;29:963–969. doi: 10.2337/diacare.295963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schunk M, Reitmeir P, Schipf S, et al. Health-related quality of life in subjects with and without Type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of five population-based surveys in Germany. Diabetic medicine: a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2012;29:646–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strom Williams JL, Lynch CP, Winchester R, Thomas L, Keith B, Egede LE. Gender differences in composite control of cardiovascular risk factors among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2014;16:421–427. doi: 10.1089/dia.2013.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Cagliero E. Sex disparities in treatment of cardiac risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 2005;28:514–520. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seghieri C, Policardo L, Francesconi P, Seghieri G. Gender differences in the relationship between diabetes process of care indicators and cardiovascular outcomes. European journal of public health. 2016;26:219–224. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phan HT, Blizzard CL, Reeves MJ, et al. Sex Differences in Long-Term Mortality After Stroke in the INSTRUCT (INternational STRoke oUtComes sTudy) A Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. 2017:10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathur P, Ostadal B, Romeo F, Mehta JL. Gender-Related Differences in Atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy/sponsored by the International Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 2015;29:319–327. doi: 10.1007/s10557-015-6596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Recarti C, Sep SJ, Stehouwer CD, Unger T. Excess cardiovascular risk in diabetic women: a case for intensive treatment. Current hypertension reports. 2015;17:554. doi: 10.1007/s11906-015-0554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dantas AP, Fortes ZB, de Carvalho MH. Vascular disease in diabetic women: Why do they miss the female protection? Experimental diabetes research. 2012;2012:570598. doi: 10.1155/2012/570598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2014;2:474–480. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krag MO, Hasselbalch L, Siersma V, et al. The impact of gender on the long-term morbidity and mortality of patients with type 2 diabetes receiving structured personal care: a 13 year follow-up study. Diabetologia. 2016;59:275–285. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]